Abstract

The Sustainable Development Goals have galvanized efforts to improve access to higher education globally. While higher education has expanded over the last decade, access inequities endure, with economic deprivation, gender, and other dimensions of marginalization shaping individual opportunities to engage with higher education. Regional differences have also emerged, with some higher education systems growing at a rapid pace, driven by a variety of policy initiatives. This paper explores higher education access inequities in the Southeast Asian context, where a period of rapid higher education expansion has recently given way to complex patterns of access, against diverging national directions for higher education development. Using large-scale nationally representative data from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), this paper traces patterns of inequitable higher education access in eight Southeast Asian countries over time. This paper then discusses country-specific policy initiatives, and the levers they deploy in trying to lower higher education inequities. It explores how these country-specific policy initiatives aiming at equality or equity in higher education access sit alongside periods of sector expansion and wealth-based gaps in higher education access, to conclude about potential policy shifts which may support work towards more equitable systems.

1. Introduction

Higher education continues to yield high returns, from facilitating greater social mobility and career prospects for individuals, to advancing economic growth and human capital development at the national level (McKenzie et al. 2025). Globally, expanding higher education access has become a cornerstone of policy initiatives and reforms (Altbach et al. 2019), yet disparities persist. Expansion has partly emerged as a response to the UN Sustainable Development Goals tasking nation states to “ensure equal access for all women and men to affordable and quality technical, vocational and tertiary education, including university [by 2030]” (UNGA 2015, p. 17). However, expansion has not necessarily been accompanied by growth in the equality of opportunity in relation to higher education access. Instead, research in countries across the economic development spectrum suggests socio-economically advantaged students continue to benefit most from such expansion. In Britain, Boliver (2011) finds that all social classes benefited during the period of higher education massification between the 1960s and early 1990s. Yet the access gap stayed the same, with individuals from privileged class origins becoming beneficiaries of both greater higher education opportunities and higher enrolment in prestigious universities. This is mirrored in evidence from China (Gu et al. 2022) and Brazil (McCowan 2016), with such inequalities still being reflective of the situation at the time of the introduction of higher education targets in the Sustainable Development Goals, across low- and middle-income countries (Ilie and Rose 2016). Inequities in access to higher education also manifest across other axes of marginalization—such as gender and rurality—and often intersect with each other and evolve over time (Byun et al. 2012; Ilie et al. 2021). In some cases, reaching access parity on one dimension may coincide with growing disparities in others (Shukla and Mishra 2024).

In Southeast Asia, the focus of this paper, inequity in higher education access remains prevalent, with economic, social, and educational factors intersectionally shaping people’s opportunities to engage in higher education (Kitamura 2016; Pinitjitsamut 2009; Vu Hoang and Nguyễn 2018). This is despite a range of policy initiatives that have looked to address such inequities. Some of these policies have targeted specific groups traditionally under-represented in higher education, while others have taken a distinctly intersectional approach, looking to reflect the nature of the inequality of opportunity in each context. For instance, the affirmative action policy in Malaysia has looked to increase access for ethnic minorities (Malakolunthu and Rengasamy 2017), while the provision of tuition waivers and stipends to low-income students in Vietnam (Tran et al. 2023) has deployed a financial lever to equalize opportunities. The adoption of low tuition fees in Myanmar (Lall 2021) and the Bidikmisi Scholarship Program in Indonesia have both targeted high-achieving less privileged students (Mulyaningsih et al. 2022) with the aim of increasing their higher education enrolment. Such policy initiatives have also had to contend with evolving political contexts (Un and Sok 2022), armed conflict (Htut et al. 2022), and the complex processes of regional policy alignment that must be understood as more than policy diffusion (Chou and Ravinet 2017).

In this paper, we first provide an overview of the evidence on inequities in higher education access in the region and of the policy background associated with this. We then answer two main research questions. First, how have patterns of higher education access evolved over time in Southeast Asia? Second, and within this, how do different aspects of marginalization, including socio-economic deprivation, gender, and rurality, interact to shape opportunities for access to higher education over time? Across these research questions, the intersectional experience of higher education access opportunities is central. Specifically, we recognize the importance of gender as a factor which may exacerbate other forms of marginalization (Raftery and Hout 1993) in relation to higher education access. The framing of the SDGs primarily, but not exclusively, around issues of gender (UNGA 2015) renders this aspect particularly salient in the global debate. We retain, however, a focus on socio-economic circumstances, since material and social deprivation pose barriers to higher education access, as the evidence discussed in the next section strongly suggests.

2. Evidence Background

Substantial evidence points to enduring inequities in access to higher education globally (Carpentier and Unterhalter 2011; Salmi 2023). In this paper, inequity reflects a lack of “equality of opportunity” (McCowan 2007) to access higher education regardless of one’s individual background. This perspective allows for inequalities in access to higher education as long as they are predicated on individuals’ non-constrained choices, i.e., only driven by factors within their control. But any differences in how people access higher education based on the intersection of personal and structural factors are deemed inherently unfair. They are also a potential target for policy action.

Long-term trends in access inequities emerge against a backdrop of the (intended) global expansion of higher education and the policy approaches underpinning them (Altbach et al. 2019). As economies expand, labor market structures change and the demand for particular skills increases. Specifically, and following modernization theory, rising demand for a knowledge-based workforce would encourage more individuals across different socio-economic backgrounds to participate in higher education (Bell 2018; Parsons 1964). This would ultimately diminish educational inequalities (DiPrete and Grusky 1990), which may change the shape of economic returns to (higher) education, and therefore also the income inequality patterns (Patrinos 2021) that influence higher education access in the first place.

This perspective does not account, however, for the structural barriers that individuals face when looking to access higher education (Bourdieu and Passeron 1990; Collins 2019), and so unfair inequities would remain. This is shown empirically. For instance, less privileged students are more likely to drop out of school before participating in higher education (Chea 2019) and perform less well against higher education admissions requirements even if they have completed secondary school (Rosenbaum and Becker 2011).

In the absence of targeted interventions, expansion would therefore not automatically bring about equality of opportunity. This is because socio-economically advantaged individuals would monopolize the new opportunities emerging as higher education systems expand. With educated and affluent parents and networks, these individuals would have greater access to social and cultural capital (Buchmann and Hannum 2001; Shavit and Blossfeld 1994). This would translate into higher opportunities to perform better academically, to meet higher education admissions requirements more easily, and to therefore access higher education at higher rates. This is the key tenet of maximally maintained inequality (Raftery and Hout 1993), alongside the proposition that the opportunities of less privileged individuals to access higher education would only increase if the demand from advantaged counterparts to participate in higher education were to be satisfied and, simultaneously, the supply of higher education places would expand beyond the demand from advantaged individuals.

This theoretical perspective finds empirical support. For instance, a cross-country analysis by Shavit and Blossfeld (1994) in 13 high-income countries suggests that despite an increase in the number of university seats, inequalities persist as these seats are predominantly filled by students from more affluent backgrounds. This scenario is also prevalent in many low- and lower-middle-income countries, where higher education opportunities remain unequal. For instance, Buckner and Abdelaziz (2023) observe patterns of higher education attendance in 117 countries to explore inequalities by wealth and country income group. Their findings reveal how countries with higher income levels tend to have higher attendance rates across all in-country wealth groups, even as gaps between these groups persist. Within low- and lower-income contexts, overall access is relatively lower than in higher-income economies, but the inequities are larger (Buckner and Abdelaziz 2023).

These above gaps are intersectional in nature. Sánchez and Singh (2018) observe heterogeneity in higher education access by gender and rurality: young women from India and Peru residing in rural areas are less likely to participate in higher education than young men. This pattern reversed in the case of Vietnam, where we notice a pro-female advantage in rural areas. Meanwhile, Zhu (2010) finds that interactions between ethnicity and area of residence shape access opportunities in China. Across these contexts, gender and ethnicity also shape opportunities around primary and secondary education (Filmer 2005 for an authoritative analysis across 44 countries; Zhao et al. 2023 for a discussion of equity in India), and later influence higher education access, with wealth being a protective factor against low early learning levels (Ilie et al. 2021).

Prior country-specific studies in Southeast Asia, albeit limited, reveal such intersectional patterns. In Cambodia, Chea (2019) highlights how, despite higher education expansion, more privileged students residing in the capital city tend to monopolize the additional opportunities. Similarly, Myanmar illustrates a pattern of higher education expansion but enduring intersectional inequities: while access has grown over time (up to the current military conflict), rurality compounds economic deprivation to limit opportunities for access against a backdrop of regional higher education institutions and marked wealth-based gaps in earlier education (Phyo 2024).

The above evidence lends support to a maximally maintained inequality perspective. It also raises important limitations of this understanding of the consequences of higher education expansion, reflective of existing theoretical critique. Specifically, this perspective does not fully acknowledge the stratification of higher education institutions or that social stratification may interact with this differently across national contexts (Lucas 2001; Breen and Jonsson 2005). The critique crystalizes in the effectively maintained inequality perspective (Lucas 2001), which offers an explanation for the continued advantage of wealthier individuals even as systems expand: privileged students take advantage of their socio-economic status to gain greater access to “both quantitatively and qualitatively better outcomes” (Lucas 2001, p. 1652) by leveraging the stratification of higher education institutions and accessing more prestigious universities, often with higher economic returns (Psacharopoulos and Patrinos 2018). This stratification takes a variety of shapes and is context-dependent (Marginson 2016): public universities are deemed to be of higher quality and prestige in Thailand and the Philippines (Gerona and Villaruz 2023; Kheir 2021b) whereas regionality is the key quality consideration and pre-conflict reform angle in Myanmar (Win 2015). Additionally, policy efforts to equalize opportunity may only affect certain institutions or sectors, for instance, how the reservation policy introduced by the Indian government predominantly initially affected public, but not private, higher education institutions, while the latter were often those that catered to historically marginalized groups (Weisskopf 2004). This aspect of stratification is highly relevant to an intersectional perspective to higher education access to ensure a consistent approach to both individual and institutional perspectives. In the context of this paper, the availability of data does not allow for this granularity of analysis, either in terms of the stratification of institutions (and therefore an effectively maintained inequality perspective) or a definition of access being having ever attended higher education.

3. Higher Education Policies Overview

Countries in Southeast Asia have experienced an expansion of higher education access since the 1970s (Wu and Hawkins 2018). This has been primarily attributed to the growing demand for a skilled workforce as well as the need for national socio-economic development (Lim et al. 2022). Official statistics (UNESCO Institute for Statistics 2025) suggest that, in particular, the last three decades have seen more than a doubling in the overall size of higher education systems in ASEAN countries, with gross enrolment rates going from 18 per cent in 2000 to 42 per cent in 2023. Within this, however, and as this paper will explore, both the rate of expansion and the size of the respective higher education systems vary substantially by country.

Alongside different patterns of higher education sector growth, countries in the region have also deployed different policy initiatives to minimize higher education access inequities and specifically wealth gaps. In what follows, we describe these policies in terms of the key levers they have deployed to provide a comprehensive policy backdrop to the analysis reported later on.

Tuition fee policy reforms take the center stage in equity efforts in the region. For instance, in the Philippines, the government implemented the Universal Access to Quality Tertiary Education Act in 2017, where students could pursue their first undergraduate degree at a public university for free. Despite the initiative increasing the enrolment rates across all socio-economic classes, some raise concerns over how most seats would have been monopolized by students from advantaged backgrounds considering how public institutions such as the University of the Philippines Diliman are regarded as having higher prestige than private HEIs (Gerona and Villaruz 2023). Others note its impact on the survival of private universities (Tullao and Ruiz 2022). Several other countries such as Myanmar and Thailand adopt a low tuition fee model (Lall 2021; Punyasavatsut 2013), yet it is beyond the reach of students from disadvantaged backgrounds. Whether these measures widen access for the intended groups is still an area for further exploration.

In addition, many governments alongside external donor agencies have implemented financial aid programs. In Indonesia, the Bidikmisi scholarship programs, introduced in 2010, provide tuition assistance and a stipend to students from economically underprivileged backgrounds with a good academic record (Wanti et al. 2022). Similarly, both merit- and need-based scholarships, albeit limited in amount and availability, are offered in Myanmar (Lall 2021), Cambodia (Hun 2024) and the Philippines (Olapane et al. 2025). Although less common in the region, Thailand implemented low-interest loan schemes in 1996 to make pursuing higher education more affordable for students from rural or low-income areas who are often at risk of exclusion (Crocco and Pitiyanuwat 2022). Vietnam adopted a similar, yet with limited coverage, scheme in 2003 (Doan et al. 2020). These policy initiatives appear to widen opportunities to access higher education for lower-income students, but mitigating financial obstacles in isolation does not always translate into equitable access. Traditionally under-represented students still encounter other structural disadvantages such as prior schooling attainment and university entry requirements.

Another notable equity initiative is the provision of affirmative action. Laos introduced a quota system of admission to reserve university seats for high-achieving students from each province, particularly women and ethnic minorities (Jeong and Hardy 2025; Siharath 2010). Similarly, in Indonesia, the 12/2012 Higher Education Act legally mandated the Bidikmisi scholarship programs, required PTN (Perguruan tinggi negeri, “public universities”) to reserve 20 per cent of university seats for outstanding students from socio-economically disadvantaged or from rural, remote, and disadvantaged areas, and launched the ADIK Papua/3T program which targets students from less developed areas by offering them lower admission thresholds, tuition assistance, and living allowances (Brewis 2019). Similar programs were previously introduced in 2003 and 2009 but were overturned in 2010. Cambodia illustrates another example. In 2008, the government launched the Special Priority Scholarship (SPP) program which targets low-income students residing in both capital city and rural areas through the provision of tuition waivers and living allowances. Nonetheless, Hun (2024) notes how the government struggles to maintain the program because of resource limitations. In 2014, through its comprehensive scholarship program, the government offers tuition waiver scholarships and living allowances to students based on academic merit, socio-economic status, as well as their eligibility in these categories: high-achieving, orphans, indigenous communities, and low-income backgrounds. Yet, privileged students would distort their economic standing during the application process, leading to errors in the scholarship selection process (Leth and Heang, cited in Hun 2024). Missing in these affirmative action initiatives which are grounded in a meritocratic approach is the acknowledgment of how disparities in the quality and accessibility of prior schooling means that the target groups do not enter university on an equal footing.

Other policy initiatives have looked to re-dress what is seen as a gender bias by introducing access quotas. For instance, in Myanmar, the policy aimed at tackling the pro-female higher education access bias now requires women to obtain higher matriculation scores than men to be admitted to certain institutions (Maber 2014). This ignores other pro-male biases in the education system.

One of the defining characteristics of expansion in the region is how several governments have approved and embraced privatization. For instance, higher education is heavily privatized in the Philippines, driving the massification of higher education in the country to a position ahead of some high-income countries in the 1970s (Perlman 1978). In 2018, 53 percent of higher education graduates were enrolled in private universities (Saguin 2022). Such a pattern could also be observed in Thailand where the Private College Act 1969 was enacted because of the limited seats available in public universities. Despite the private sector comprising more than 48 percent of HEIs in 2015, more students were enrolled in public universities (Crocco 2018; Kheir 2021b). The same holds for Timor-Leste (Ximenes 2024) and Vietnam (Kheir 2021c). Despite several private HEIs, public universities are preferred because the public holds them in very high regard (Kheir 2021c). Unlike other countries where privileged students tend to choose private HEIs, trends observed here suggest how students, in general, favor public universities.

Finally, what stands out in some countries in the region is the impact of political instability on higher education access. In Cambodia, during the Khmer Rouge in mid-1970s, the entire higher education system was on the brink of total collapse (Kheir 2021a), following university closures and arrests of intellectuals. Myanmar encountered frequent closures and the reopening of the universities between 1988 and 1990 following the student-led 8888 uprising (Lall 2021). These uprisings later resumed, prompting the opening of distance higher education and the establishment of regional universities to disperse students from organizing further protests (Heslop 2019). Thailand and Timor-Leste had similar temporary closures of universities due to the crackdown on student activism in 1973–1976 and 1999, respectively, putting higher education in a state of crisis.

The broad policy patterns above reveal mass expansion in the region, accompanied by several equity schemes, privatization, as well as the impact of political instability in some countries. Situating this policy overview against the trends of higher education access is imperative to understand which countries are progressing and which are falling behind the 2030 target. Equally important is exploring the status of equity within each country to understand the diverging trends and complex interactions between wealth and other background factors.

4. Data and Method

4.1. Data Source

We use cross-sectional, nationally representative, individual-level data from two sources: the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) (DHS Implementing Partners and ICF International 2022) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) (UNICEF 2022). We chose the DHS and MICS for three reasons. First, although they are not educational surveys, they include variables relevant to our research questions, including highest educational level achieved, gender, and wealth background (a wealth index), as well as further demographic characteristics such as year of birth. Second, they provide good coverage of the populations of the Southeast Asian countries in our study, allowing for cross-country comparisons. Although not all countries in the region are included in the analysis, the available data is sufficient to draw comparisons on the overall patterns of higher education access to better understand the region’s progress towards achieving equitable access to higher education. Third, both DHS and MICS data are available to registered researchers with minimal practical hurdles, offering anonymized individual-level microdata that emerges from cross-nationally harmonized studies.

4.2. Sampling Approach of the Surveys

Both the DHS and MICS employ a two-stage stratified cluster sampling design. First, clusters (or primary sampling units) are randomly selected from the master sample based on each country’s population census. Second, systematic sampling is used to identify households from the selected clusters. These procedures ensure a nationally representative sample.

Given that the raw samples of these sources are not self-weighted, we apply sampling weights provided by each respective survey. To ensure young individuals have at least had the opportunity to access the higher education level at the time of each survey, we restrict the sample to individuals aged 25 and over at the time of the survey. This does not capture all higher education entrants of all ages—evidence in the region (e.g., Ramirez Yee 2024 for the Philippines) does suggest that at least some of the systems under exploration here are relatively closed off to older-age entrants. This represents an access inequity in and of itself but renders this analysis slightly more externally valid.

To ensure we capture the same birth cohorts (with the oldest being born in 1946), and because of the different timing of the survey in each country, we restrict the upper age bound to 69 for Myanmar, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Laos, and to 75 for Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Thailand. The full analytical sample per country is illustrated in Table 1.

Table 1.

Analytical sample.

4.3. Measures

4.3.1. Higher Education Access

Our key outcome variable is a binary measure capturing higher education access. The DHS and MICS ask respondents for their highest education level (see Table 2 for the raw distribution by country of stated levels of education achieved). In our study, higher education includes all post-secondary education programs in both private and public sectors. Using this information, we code higher education access as “1” if the respondent has ever participated in higher education by the time of the survey and “0” otherwise. We therefore take “access” to mean “participation ever”, in higher education.

Table 2.

Distribution of levels of education, unweighted.

There are several conceptual limitations to this approach. First, it does not allow us to explore the differences in access across the status and type of higher education institutions. Second, this definition means we include individuals who entered higher education but dropped out prior to completion and treat them the same as completers. This is despite evidence that drop out from higher education is shaped by the same range of factors affecting access overall (e.g., Tentshol et al. 2019, for Thailand). The key implication of this approach—the only possibility given the available data—is that the analysis likely reflects an over-estimation of access compared with a more granular understanding of access (including persistence and completion, the rates of which would be lower). The previous policy exploration in this paper does not seek to attribute the observed rates of access to specific policies, and the assumption is that any analysis underpinning the policies’ deployment would have used more granular data available to national governments but not available for research.

4.3.2. Independent Variables

To obtain a parsimonious model, we only include independent variables which benefit from support in the empirical literature in terms of their association with higher education access and are available in our datasets.

Our main explanatory factor of interest is wealth, for which we use the “household wealth index” as a proxy (Rutstein and Johnson 2004), split into five quintiles for each country in the analysis. This index is computed using housing characteristics and household possession data, such as vehicles and TV sets, and is country-specific but constructed in such a way as to enable cross-country comparison in terms of relative positioning in the wealth distribution. For this, both DHS and MICS divide households into wealth quintiles, from poorest to richest, which we use to describe inequities in higher education access.

We also observe differences in higher education access across gender, using a binary variable distinguishing between females and males; and rurality, again using a binary variable distinguishing between rural and urban locations. We acknowledge the limitations of both these variables in terms of a more granular understanding of both rurality and gender.

4.4. Analytical Approach

We first trace the historical development of higher education access in each country. Due to a lack of longitudinal data, we instead rely on estimates of the highest level of education ever achieved (with higher education as the focus) for sequentially older birth cohorts (Gruijters 2022; Ilie and Rose 2016). Specifically, we divide the sample in each country into 5-year birth cohorts, generating nine birth cohorts in Myanmar, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Laos and ten cohorts in Vietnam, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Thailand. We then estimate the higher education access rates of each cohort relative to each cohort size (the “net” higher education access rate).

Next, we employ linear probability models with within-country region fixed effects to examine the relationship between wealth and higher education access across different cohorts in each country. We chose linear probability models over other commonly used regression techniques such as probit or logit because it is much easier to interpret the coefficients (Fairlie and Sundstrom 1999).

First, we describe the raw rates of higher education by country, cohort, and wealth quintile. We then build our models sequentially. First, we use the wealth groups as the sole predictor to observe its effect on higher education access across cohorts (Model 1). These results add statistical testing to the descriptive statistics above and allow us to understand which of the observed gaps are statistically significant. We then include the wealth quintiles, gender, and rurality (Model 2). This model does not allow us to observe whether wealth-based gaps vary by gender and by rurality. We therefore add the interaction terms between wealth and these two factors into Model 3. We estimate all these models with within-country region fixed effects and separately for each country. Our regression models take the following form:

where the outcome variable Yir takes the value of 1 if individual i in region has ever participated in higher education and 0 if otherwise. α is the intercept. The wealth variable captures the wealth quintiles in each country, and β1 the coefficients for each wealth quintile; β2 is the vector of coefficients for the further independent variables of gender and rurality captured in Xi. β3 and β4 are the coefficients for the interaction terms between wealth and, respectively, gender and rurality. The region fixed effects are captured in ur and 𝛜ir is the error term for each respective model.

Yir = α + β1·wealthir + ur + 𝛜ir

Yir = α + β1·wealthir + β2·Xi + ur + 𝛜ir

Yir = α + β1·wealthir + β2·Xi + β3·wealthir × genderir + β4·wealthir × ruralir + ur + 𝛜ir

While the linear probability modeling approach we take is common, it does not account for the potential nonlinearity in the estimated relationship. To check the robustness of our results, we also run all the above models as logistic regression models. Notwithstanding the caveat that, for Model 3 in particular, some observations are removed from the analysis because they fall within subgroups defined by the predictors where there is no variation in the outcome (usually, no higher education access for the poorest in rural areas), the overall results we obtain are consistent with the linear probability specification. We therefore retain it and present those results here.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, due to data limitations, we could not capture variables such as prior academic attainment (Ilie et al. 2021; Sánchez and Singh 2018) and higher education aspirations (Sánchez and Singh 2018), which are found to be highly correlated with higher education access. Second, the wealth variable does not include a consideration of other common aspects of socio-economic status, such as parental education and occupation (Duncan et al. 1972), although it is based on a benchmarked possessions index that differentiates between households and individuals. Third, the generation of consecutively older cohorts may introduce bias in terms of the varying mortality rates (and therefore representation in these cross-sectional surveys) by the very factors that we seek to explore. Evidence from the Asia Pacific region points to prevalent socio-economic gradients in mortality rates that differ by country and over time (Xu et al. 2024). One way to mitigate this bias resides in our approach to identify, across the countries in the analysis, birth cohorts, rather than rely solely on the timing of the survey. This allows some cross-country comparability. Fourth, neither source survey provide data to distinguish between public and private universities or capture the academic rankings of the universities. This therefore does not allow for a differentiation by these supply-side aspects (or indeed the empirical operationalization of an effectively maintained inequality perspective), but the analysis is able to capture the important time trends and the broad size of respective higher education systems.

Notwithstanding the above limitations, the analysis sheds light on the intersectional patterns of higher education access by the wealth, gender, and rurality in each of these countries.

5. Findings

5.1. Wealth-Based Gaps in Higher Education Access over Time

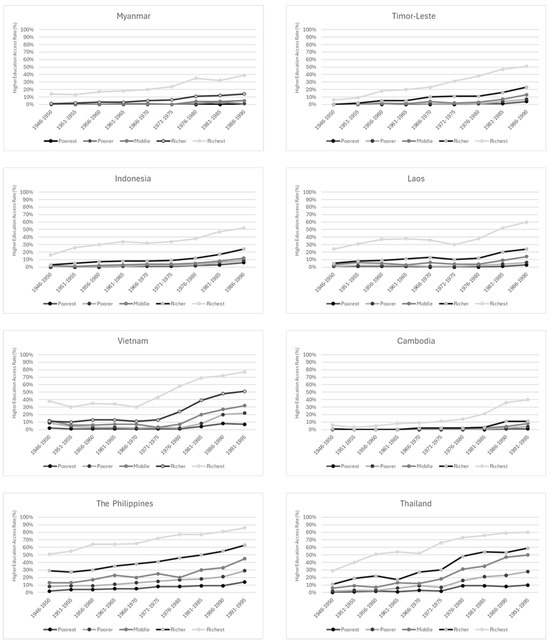

Figure 1 describes how the raw patterns of higher education access across the wealth quintiles evolve over time. Across the Southeast Asian countries in our analysis, the access rates for students from the richest group exhibit a steady upward trajectory. In the Philippines and in Thailand, individuals from the richest quintiles of birth cohorts after 1976 exceed the 70 percentage point higher education access rate (normally a gross enrolment rate) threshold now commonly reported by high-income nations. One possible reason behind the relatively high access rates in these countries would be the early availability of higher education institutions. In the Philippines, for instance, both public and private universities came into existence during the American colonial period (James 1991; Saguin 2022), and Thailand has deployed the privatization and massification of higher education policies since the late 1960s (Crocco 2018).

Figure 1.

Patterns of higher education access by country, cohort, and wealth quintile.

In contrast, the raw access rates illustrated in Figure 1 show only marginal growth for the poorest and second poorest quintiles. For these two poorest quintiles, the oldest cohorts consistently show null rates of higher education access across all countries in the analysis. For the poorest quintile, the access rate does not rise above 10% even for the most recent birth cohorts, including in the Philippines and Thailand, where access rates are comparatively higher overall.

The middle quintile shows a pattern of change more consistent with the shown growth of the poorer two quintiles, rather than the richer groups. In Cambodia, the second richest quintile also mirrors this pattern, while in the other seven nations this group consistently fares as expected: better than the middle quintile, but less so than the richest.

Across this pattern of growth, wealth-based gaps in higher education widen over time, even as all these systems show overall expansion over time. Myanmar is the country with the lowest overall rate of higher education in our analysis, and here the gaps between the poorest and the richest grows from 14 percentage points for the oldest cohort to 38 percentage points for the youngest cohort. At the opposite end of system size, the equivalent wealth gap in Thailand is 29 percentage points for the older cohort and 70 percentage points for the youngest cohort. This suggests substantial inequities in access by wealth, and while overall growth is observable, this is not at all uniformly distributed to wealth groups.

5.2. Gaps in Higher Education Access by Wealth, Gender, and Rural–Urban Location

The above results illustrate the unadjusted wealth-based gaps in higher education access. Table 3 below illustrates the magnitude (and associated statistical significance) of the wealth-based gaps in access when gender and rurality are considered (estimates from the Model 1 and the Model 2 specification above). We find that the wealth-based gaps in higher education access are smaller once gender and rurality are controlled for, especially across earlier cohorts, and for most countries. For the sake of brevity, Table 3 only captures these wealth-based gaps for the oldest, middle, and youngest cohort in each country in the analysis.

Table 3.

Estimated wealth-based gaps in higher education access by country and cohort.

The first key pattern in Table 3 is that, across progressively younger cohorts, individuals in the richest quintiles are consistently statistically significantly more likely to have accessed higher education than their poorest counterparts, whether or not gender and rurality are accounted for. For the oldest cohorts, this gap ranges from 4 percentage points in Cambodia to 53 percentage points in the Philippines (both differences statistically significant at the 0.1% level). For the youngest cohorts, this gap is higher in each of the eight countries in the analysis, ranging from approximately 40 percentage points in Cambodia to 81 percentage points in the Philippines (both differences statistically significant at the 0.001 level).

The second key pattern illustrated in Table 3 is that, in most countries in this analysis, the wealth-based gaps in higher education access diminish but still retain the overall patterns of statistical significance as for uncontrolled gaps, when gender and rurality are considered (Model 1 v Model 2 results). This reiterates the compounding effect between wealth and, respectively, gender and location identified in other low- and lower-middle income countries (Sánchez and Singh 2018). However, the magnitude of the wealth gap reduction varies by country. In Myanmar, the addition of gender and rurality controls reduces the gap between the richest and the poorest wealth quintile by 5 percentage points for the oldest and youngest cohorts. The reduction in the wealth-based gap is approximately half of this in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, Cambodia, the Philippines, and Thailand, but double in Vietnam, suggesting a stronger association of gender and rurality with access in the latter. The small gap reductions once gender and rurality are controlled for in the Philippines (and to some extent Thailand) may be because gender and rurality are not, independently of wealth, key factors that shape higher education access against the recent expansion of these systems (Saguin 2022).

Table 4 below illustrates both the gender gaps and the rurality gaps, for all birth cohorts, controlling for wealth (results from Model 2). In the oldest cohorts, countries in the analysis either exhibit a pro-male gap (a statistically significant pro-male gap in Myanmar, Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Cambodia, of between 2 and 10 percentage points) or no statistically significant gender gap (in Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand). In the youngest cohorts, most countries show statistically significant pro-female gaps of between 2 and 12 percentage gaps (Myanmar, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Thailand); the other three countries conversely exhibit relatively smaller, but still statistically significant, pro-male gaps of between 2 and 6 percentage points.

Table 4.

Estimated gender and rurality gaps in higher education access, by country and cohort, controlling for wealth.

Table 4 above also shows that, controlling for wealth and gender, rurality is associated with a lower probability of higher education access across most countries and most cohorts. In Myanmar, Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand, the urban–rural gap in access is statistically significant for all cohorts and of a magnitude comparable to that of the previously reported gender gaps. In the other four nations, the urban–rural gaps are occasionally non-statistically significant. For Indonesia and Cambodia, the statistically similar levels of access by rurality may be due to these countries’ explicit priorities to increase the enrolment of students from rural and low-income backgrounds, through the provision of tuition assistance and living allowances (Bhatta et al. 2024; Mulyaningsih et al. 2022), while in the Philippines this may be related to the 2017 introduction of a tuition-free model in public universities or because urban students may be studying abroad, the latter of which is not captured in the sampling strategy of either the DHS or MICS.

5.3. Wealth Interacting with Gender and Rural–Urban Location

So far, the inclusion of gender and rural–urban location in Model 2 has broadly shown a reduction in the wealth gaps in higher education access; meanwhile gender and rurality-based gaps persist even after accounting for wealth. This suggests that these two factors may moderate the relationship between wealth and access. Model 3 therefore accounts for this by including two interaction terms, between wealth and gender and rurality.

The results from Model 3 (Table 5 below) show that gender interacts with wealth to shape higher education access. In particular, it is women from the richest wealth quintiles who drive the observed rates for higher education participation for women for the youngest cohorts in most countries: a statistically significant positive interaction in Myanmar, Vietnam, and Thailand; a statistically non-significant interaction in Timor-Leste, Indonesia, and Laos. In Cambodia and the Philippines, the richest women are statistically significantly less likely than the poorest women to have accessed higher education.

Table 5.

Estimated main and interaction effects: wealth and gender and rurality gaps in higher education access, by country, for the oldest, middle, and youngest cohorts only.

Over time, Thailand and the Philippines show increasingly positive interactions between female gender and the wealthier quintiles over the cohorts. For Thailand, the female and richest quintile interaction moves from −0.035 to +0.115 (both statistically significant at the 5% level). This pattern is also exhibited in Vietnam, for both the richest and the second richest quintile and the gender interaction. The gender interaction pattern is more mixed over time in other countries.

Table 5 also illustrates the interaction between rurality and wealth (accounting for the main and gender interaction effects too). Broadly, the differences between rural and urban students from the two poorer and middle quintiles relative to the poorest are statistically non-significant across the countries in our analysis, with the exception of the middle quintile interaction with rurality in the youngest cohorts in Thailand and the Philippines. This suggests that for the poorest three quintiles, rurality is not associated with lower higher education access opportunities.

At the other end of the wealth distribution, however, the differences are stark. The richest quintile in rural areas shows much lower rates of higher education access, suggesting that wealth is not protective against the lower opportunity to access higher education associated with coming from a rural context; this interaction shows the strongest effect sizes in Table 5, which are mostly negative and the vast majority statistically significant.

The fact that in most of the countries in the analysis the main effect of rurality becomes statistically non-significant when interacting with wealth quintiles (and including the wealth and gender main effect, as well as the gender–wealth interaction, as per Model 3) suggests how important the understanding of the wealth distribution within rural and urban areas is. Overall, this indicates that policy initiatives that target rural settings should also consider the variation in the economic circumstances of those residing there, and that research exploring other factors associated with rurality and higher education access (and not included in this paper) is required.

On the whole, this analysis suggests complex intersections between gender and rurality with wealth specific to each country’s context, and the persistence of gaps in higher education access by the interaction of these dimensions of marginalization despite policy efforts. The analysis shows that the expansion of higher education is not associated with a narrowing of inequities but rather an increasing complexity of the interplay between the key aspects of gender and rurality and socio-economic background The intersectional nature of higher education access therefore comes to the fore in this analysis and remains an aspect to be considered by future research.

6. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has examined the trends of higher education access across eight countries in Southeast Asia, with a focus on wealth, gender, and rurality. Our analysis provides insights to contextualize the progress observed in both individual countries and the entire region against the backdrop of the UN 2030 Sustainable Development Goal 4.3, which calls for equal access to higher education. While the analysis has made use of nationally representative data, it has not been able to capture either institutional heterogeneity and stratification or individual’s prior attainment. These are both factors—the former on the supply side, the latter on the demand side—that influence opportunities to access higher education. We therefore strongly recommend that, where possible, large-scale data collection efforts include such information, even if only self-reported, to enable future analyses to consider the wider constellation of aspects which theoretical understandings of higher education access inequities require.

By and large, expansion in the region has increased higher education opportunities. Yet, we also observe wealth-based gaps in access to have widened over time, placing the poorest groups at an increasing disadvantage. Our findings therefore follow the pattern of maximally maintained inequality, which has also been identified in other low- and middle-income countries (Gruijters 2022; Ilie et al. 2021; Torche 2010). This is despite both financial and affirmative action-type policy initiatives which look to precisely target the poorest in society. The question, to be answered by policy-specific research in the future, is whether those targeted are actually reached by these policies and how other structural factors may prevent their access. This represents a potential barrier to policy impact that has remained unexplored in this paper, but may offer a reason why, despite their implementation in nationally specific ways, policies have not led to an equalization of opportunities in relation to higher education access.

Furthermore, we observe gender differences in access across cohorts. In Timor-Leste, Cambodia, and Laos, young men tend to have more opportunities to access higher education than women, holding all else constant. The remaining countries however exhibit a pattern slightly favoring young women, especially most recently. This occurs against a backdrop of gender party-oriented policies, for instance Cambodia’s need-based scholarships and Laos’ Quota System of Admission for young women. Further and more granular evidence is needed of these policies’ impact overall and how this may have evolved over time.

Similarly, rurality-based gaps remain throughout, which are consistent with the previous findings in the region (Chea 2019; Vu et al. 2013; Ramirez Yee 2024). The persistence of such gaps despite the establishment of public universities in rural and less-developed areas in countries such as Myanmar (Lall 2021) and Laos (Ogawa 2009) calls for the need to reflect on broader systemic barriers. For instance, societal norms, limited resources, as well as the need to make earnings are some examples acting as a tide against students from rural areas (Friesen and Purc-Stephenson 2016; Liu and Ma 2018). In Indonesia and Cambodia, however, the differences in access between rural and urban students become statistically insignificant among the more recent cohorts, possibly because of their national priorities targeting students from rural and low-income backgrounds. For instance, Indonesia has implemented several fair access schemes under Law 12/2012 which include the Bidikmisi scholarship and ADIK Papua/3T programs. As for Cambodia, the 2008 Special Priority Scholarship (SPP) program offers tuition waivers and living allowances to low-income students residing in both capital city and rural areas.

Our findings also reveal how wealth interacts with gender and rural–urban location to create more nuanced patterns of marginalization. In several countries, young women from advantaged backgrounds in the youngest birth cohorts are more likely to participate in higher education than young men. Among those from poor backgrounds, the differences are less evident, emerging only in the Philippines and Thailand and supporting suggestions that where higher education systems are very small, it is the richest who disproportionately access it, so much so that any inequalities amongst the poorest are obscured by very low rates of access overall. The older cohorts in the analysis illustrate these patterns prior to the introduction of the vast majority of gender-focused policies in the countries in our analysis. We also observe, however, how such patterns of complex gender and wealth interactions, albeit somewhat less consistent, appear much more among the more recent cohorts. This would suggest that gender-focused policy initiatives may face barriers to successful impact from the intersection with wealth for the circumstances and contexts that enable access to higher education.

Likewise, urban students from advantaged backgrounds in most countries have higher chances to access higher education compared with those residing in rural areas. Rural–urban differences in other wealth groups are less evident across all cohorts. Interestingly, the Philippines is the only country where rural students from the middle-income group have a higher participation than their urban counterparts. Further research would be needed to explore if this is attributable to its financial aid programs such as the Expanded Students’ Grant-in-Aid Program, which targets high-achieving students from low-income families (Olapane et al. 2025).

These access patterns have emerged even as many countries in the region have already introduced quota systems of admission targeting women, low-income students, and/or those from rural areas (Crocco and Pitiyanuwat 2022; Hun 2024; Mulyaningsih et al. 2022; Doan et al. 2020). While not providing a detailed policy analysis of each of these initiatives, the trends identified in this paper suggest that these policies might not be reaching their intended aim and further work is required to understand their unintended consequences. Furthermore, since our findings suggest that the effect of wealth on higher education access persists and even intensifies over time, despite financial support programs, policy research may also explore how the relatively low-tuition fee systems operating in the majority of the countries in our analysis may benefit those who already have the means to afford higher education and whether the targeting of any financial support has considered other possible forms of financial barriers, either at or before the point of potential higher education access. Policy and research should also consider the fundamental differences by rurality illustrated in the analysis of access trends. With individuals from urban settings retaining an advantage in terms of their higher education access compared with their similar rural counterparts, research should explore in further depth what factors, beyond material deprivation, access to education, and others well documented in the literature (e.g., Zhao et al. 2023), shape these access opportunities. These may include a consideration of local (infrastructure, distances to educational settings) or personal factors (family structures, cultural values, risk appetite even at the same level of economic resources, etc.), and how policies to equalize opportunities may address these in contextually relevant ways.

Overall, both policy and future research should account for the intersecting dimensions of marginalization emerging as important factors shaping higher education access. Policy responses to the different needs of these groups may be challenging but ensuring equitable access to higher education will benefit all.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.W.P. and S.I.; methodology, S.I. and L.W.P.; validation, L.W.P. and S.I.; formal analysis, L.W.P. and S.I.; writing—original draft preparation, L.W.P.; writing—review and editing, S.I. and L.W.P.; visualization, L.W.P. and S.I.; supervision, S.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

We used datasets from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) and the Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS), which are available upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Altbach, Philip G., Liz Reisberg, and Laura E. Rumbley. 2019. Trends in Global Higher Education: A Tracking an Academic Revolution. Global Perspectives on Higher Education 22. Leiden: Brill|Sense. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Daniel. 2018. The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. In Social Stratification, 4th ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatta, Saurav Dev, Saurav Katwal, Lauri Pynnönen, Somphospheak Heng, and Jamil Salmi. 2024. Reimagining Higher Education in Cambodia: Modernizing Governance for Improved Access and Relevance. Washington, DC: World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Boliver, Vikki. 2011. Expansion, Differentiation, and the Persistence of Social Class Inequalities in British Higher Education. Higher Education 61: 229–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Passeron, and Jean-Claude Passeron. 1990. Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Breen, Richard, and Jan O. Jonsson. 2005. Inequality of Opportunity in Comparative Perspective: Recent Research on Educational Attainment and Social Mobility. Annual Review of Sociology 31: 223–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brewis, Elisa. 2019. Fair Access to Higher Education and Discourses of Development: A Policy Analysis from Indonesia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 49: 453–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, Claudia, and Emily Hannum. 2001. Education and Stratification in Developing Countries: A Review of Theories and Research. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 77–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckner, Elizabeth, and Yara Abdelaziz. 2023. Wealth-Based Inequalities in Higher Education Attendance: A Global Snapshot. Educational Researcher 52: 544–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byun, Soo-yong, Judith L. Meece, and Matthew J. Irvin. 2012. Rural-nonrural disparities in postsecondary educational attainment revisited. American Educational Research Journal 49: 412–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpentier, Vincent, and Elaine Unterhalter. 2011. Globalization, Higher Education and Inequalities: Problems and Prospects. In Handbook on Globalization and Higher Education. Edited by Roger King, Simon Marginson and Rajani Naidoo. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chea, Phal. 2019. Does Higher Education Expansion in Cambodia Make Access to Education More Equal? International Journal of Educational Development 70: 102075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, Meng-Hsuan, and Pauline Ravinet. 2017. Higher Education Regionalism in Europe and Southeast Asia: Comparing Policy Ideas. Policy and Society 36: 143–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Randall. 2019. The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, Oliver S. 2018. Thai Higher Education: Privatization and Massification. In Education in Thailand. Edited by Gerald W. Fry. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer, vol. 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crocco, Oliver S., and Somwung Pitiyanuwat. 2022. Higher Education in Thailand. In International Handbook on Education in South East Asia. Edited by Lorraine Pe Symaco and Martin Hayden. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Singapore: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DHS Implementing Partners and ICF International. 2022. Demographic and Health Surveys [Datasets 2015–2022]. Reston: ICF International. [Google Scholar]

- DiPrete, Thomas A., and David B. Grusky. 1990. The Multilevel Analysis of Trends with Repeated Cross-Sectional Data. Sociological Methodology 20: 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doan, Dung, Jiacheng Kang, and Yanran Zhu. 2020. Financing Higher Education in Vietnam: Student Loan Reform. Oxford: Centre for Global Higher Education, University of Oxford. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, Otis Dudley, David L. Featherman, and Beverly Duncan. 1972. Socioeconomic Background and Achievement. New York: Seminar Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fairlie, Robert W., and William A. Sundstrom. 1999. The Emergence, Persistence, and Recent Widening of the Racial Unemployment Gap. ILR Review 52: 252–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filmer, Deon. 2005. Gender and Wealth Disparities in Schooling: Evidence from 44 Countries. International Journal of Educational Research 43: 351–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friesen, Laura, and Rebecca J. Purc-Stephenson. 2016. Should I Stay or Should I Go? Perceived Barriers to Pursuing a University Education for Persons in Rural Areas. Canadian Journal of Higher Education 4: 138–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerona, Bernard V., and Jennifer A. Villaruz. 2023. Students’ View On Free Higher Education Policy In A University In The Philippines. International Journal of Education, Business and Economics Research (IJEBER) 3: 190–206. [Google Scholar]

- Gruijters, Rob J. 2022. Trends in Educational Stratification during China’s Great Transformation. Oxford Review of Education 48: 320–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, Xiang, Sheng Hua, Tom McKenzie, and Yanqiao Zheng. 2022. Like Father, like Son? Parental Input, Access to Higher Education, and Social Mobility in China. China Economic Review 72: 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heslop, Lynne. 2019. Encountering Internationalisation: Higher Education and Social Justice in Myanmar. Brighton and Hove: University of Sussex. [Google Scholar]

- Htut, Khaing Phyu, Marie Lall, and Camille Kandiko Howson. 2022. Caught between COVID-19, Coup and Conflict—What Future for Myanmar Higher Education Reforms? Education Sciences 12: 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hun, Seyhakunthy. 2024. Scholarship Schemes in Cambodian Higher Education: Unpacking Why Lower-Income Students Are Lagging Behind. Higher Education Policy, ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, Sonia, and Pauline Rose. 2016. Is Equal Access to Higher Education in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa Achievable by 2030? Higher Education 72: 435–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilie, Sonia, Pauline Rose, and Anna Vignoles. 2021. Understanding higher education access: Inequalities and early learning in low and lower—middle—income Countries. British Educational Research Journal 47: 1237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- James, Estelle. 1991. Private Higher Education: The Philippines as a Prototype. Higher Education 21: 189–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Daeul, and Ian Hardy. 2025. Imagining Educational Futures? SDG4 Enactment for Ethnic Minorities in Laos. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 55: 529–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kheir, Zane. 2021a. Cambodia. In Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Issue 10. Edited by Hoe Yeong Loke. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond (HESB). Singapore: The HEAD Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kheir, Zane. 2021b. Thailand. In Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Issue 10. Edited by Hoe Yeong Loke. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond (HESB). Singapore: The HEAD Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kheir, Zane. 2021c. Vietnam. In Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond: Issue 10. Edited by Hoe Yeong Loke. Higher Education in Southeast Asia and Beyond (HESB). Singapore: The HEAD Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura, Yuto. 2016. Higher Education in Cambodia: Challenges to Promote Greater Access and Higher Quality. In The Palgrave Handbook of Asia Pacific Higher Education. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. [Google Scholar]

- Lall, Marie. 2021. Myanmar’s Education Reforms: A Pathway to Social Justice? London: UCL Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, Miguel Antonio, Icy Fresno Anabo, Anh Ngoc Quynh Phan, Mark Andrew Elepano, and Gunjana Kuntamarat. 2022. The State of Higher Education in Southeast Asia. SHARE Project Management Office & ASEAN Secretariat. Available online: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/The-State-of-Higher-Education-in-Southeast-Asia_11.2022.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2025).

- Liu, Wan-Hsin, and Ru Ma. 2018. Regional Inequality of Higher Education Resources in China. Frontiers of Education in China 13: 119–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucas, Samuel R. 2001. Effectively Maintained Inequality: Education Transitions, Track Mobility, and Social Background Effects. American Journal of Sociology 106: 1642–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maber, Elizabeth. 2014. (In)Equality and Action: The Role of Women’s Training Initiatives in Promoting Women’s Leadership Opportunities in Myanmar. Gender & Development 22: 141–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malakolunthu, Suseela, and Nagappan C. Rengasamy. 2017. Policy Discourses in Malaysian Education: A Nation in the Making. Routledge Critical Studies in Asian Education. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Marginson, Simon. 2016. Global Stratification in Higher Education. In Higher Education, Stratification, and Workforce Development. Edited by Sheila Slaughter and Barrett Jay Taylor. Higher Education Dynamics. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer International Publishing, vol. 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCowan, Tristan. 2007. Expansion without Equity: An Analysis of Current Policy on Access to Higher Education in Brazil. Higher Education 53: 579–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCowan, Tristan. 2016. Three Dimensions of Equity of Access to Higher Education. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 46: 645–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKenzie, Tom, Lei Xu, and Yu Zhu. 2025. Returns to Education in the Context of Higher Education Expansion. In Handbook of Education and Work. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Mulyaningsih, Tri, Sarah Dong, Riyana Miranti, Anne Daly, and Yunastiti Purwaningsih. 2022. Targeted Scholarship for Higher Education and Academic Performance: Evidence from Indonesia. International Journal of Educational Development 88: 102510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogawa, Keiichi. 2009. Higher Education in Lao PDR. In The Political Economy of Educational Reforms and Capacity Development in Southeast Asia. Edited by Yasushi Hirosato and Yuto Kitamura. Dordrecht: Springer, vol. 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olapane, Elias, Rosario Clarabel Contreras, and Nelma Quindipan. 2025. Transforming Families through Free Tertiary Education Grants in the Philippines. Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in Education 14: 28–47. [Google Scholar]

- Parsons, Talcott. 1964. Evolutionary Universals in Society. American Sociological Review 29: 339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patrinos, Harry Anthony. 2021. The Changing Pattern of Returns to Education. What Impact Will This Have on Earnings Inequality? In Reforming Education and Challenging Inequalities in Southern Contexts: Research and Policy in International Development, 1st ed. Edited by Pauline Rose, Madeleine Arnot, Roger Jeffery and Nidhi Singal. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perlman, Daniel H. 1978. Higher Education in the Philippines: An Overview and Current Problems. Peabody Journal of Education 55: 119–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phyo, Lin Wai. 2024. Understanding Equity and Access in the Expansion of Higher Education in Myanmar. Cambridge Educational Research e-Journal 11: 310–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinitjitsamut, Montchai. 2009. The Inequality of Opportunity to Participate in Thailand Higher Education. International Journal of Education Economics and Development 1: 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psacharopoulos, George, and Harry Anthony Patrinos. 2018. Returns to Investment in Education: A Decennial Review of the Global Literature. Education Economics 26: 445–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Punyasavatsut, Chaiyuth. 2013. Thailand: Issues in Education. Education in South-East Asia 20: 275. [Google Scholar]

- Raftery, Adrian E., and Michael Hout. 1993. Maximally Maintained Inequality: Expansion, Reform, and Opportunity in Irish Education, 1921–1975. Sociology of Education 66: 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Yee, Karol Mark. 2024. At All Costs: Educational Expansion and Persistent Inequality in the Philippines. Higher Education 87: 1809–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, James E., and Kelly Iwanaga Becker. 2011. The Early College Challenge: Navigating Disadvantaged Students’ Transition to College. American Educator 35: 14. [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein, Shea Oscar, and Kiersten Johnson. 2004. The DHS Wealth Index. DHS Comparative Reports No. 6. ORC Macro, Calverton. Available online: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/CR6/CR6.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Saguin, Kidjie. 2022. The Politics of De-Privatisation: Philippine Higher Education in Transition. Journal of Contemporary Asia 53: 471–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, Jamil. 2023. Equity and Inclusion in Higher Education. International Higher Education 113: 113. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, Alan, and Abhijeet Singh. 2018. Accessing Higher Education in Developing Countries: Panel Data Analysis from India, Peru, and Vietnam. World Development 109: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shavit, Yossi, and Hans-Peter Blossfeld. 1994. Persistent Inequality: Changing Educational Attainment in Thirteen Countries. British Journal of Educational Studies 42: 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, Vachaspati, and Udaya S. Mishra. 2024. Reading Progress in Attainment of Higher Education Goals in India: Features and Characteristics. Social Change 54: 68–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siharath, Bounheng. 2010. The Higher Education in Lao PDR and Roles of International Cooperation for Its University Development—National University of Laos. Vientiane: National University of Laos. [Google Scholar]

- Tentshol, Kelzang, Rhysa McNeil, and Phattrawan Tongkumchum. 2019. Determinants of University Dropout: A Case of Thailand. Asian Social Science 15: 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torche, Florencia. 2010. Economic Crisis and Inequality of Educational Opportunity in Latin America. Sociology of Education 83: 85–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, Nguyet Anh, Trang Hong Dao, Hang Thi Banh, and Dung Kieu Vo. 2023. Policy Note on Higher Education Financing in Vietnam: Strategic Priorities and Policy Options. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. [Google Scholar]

- Tullao, Tereso S., and Mark Gerald C. Ruiz. 2022. Unintended Consequences of Free Education in Public Colleges and Universities in the Philippines 1. In Critical Perspectives on Economics of Education. Edited by Silvia Mendolia, Martin O’Brien, Alfredo R. Paloyo and Oleg Yerokhin. Routledge Studies in Modern World Economy. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Un, Leang, and Say Sok. 2022. (Higher) Education Policy and Project Intervention in Cambodia: Its Development Discourse. In Education in Cambodia. Edited by Vincent McNamara and Martin Hayden. Education in the Asia-Pacific Region: Issues, Concerns and Prospects. Singapore: Springer Nature, vol. 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNESCO Institute for Statistics. 2025. Data Centre—Theme: Education. Montreal: UNESCO Institute for Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2022. Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS) [Datasets 2017–2022]. New York: UNICEF. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), September 25. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 10 May 2025).

- Vu, Lan Thi Hoang, Linh Cu Le, and Nazeem Muhajarine. 2013. Multilevel Determinants of Colleges/Universities Enrolment in Vietnam: Evidences from the 15% Sample Data of Population Census 2009. Social Indicators Research 111: 375–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vu Hoang, Linh, and Thùy Anh Nguyễn. 2018. Analysis of Access and Equity in Higher Education System in Vietnam. VNU Journal of Science: Policy and Management Studies 34: 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wanti, Mega, Renate Wesselink, Harm Biemans, and Perry Den Brok. 2022. The Role of Social Factors in Access to and Equity in Higher Education for Students with Low Socioeconomic Status: A Case Study from Indonesia. Equity in Education & Society 2: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisskopf, Thomas E. 2004. Impact of Reservation on Admissions to Higher Education in India. Economic and Political Weekly 39: 4339–49. [Google Scholar]

- Win, Po Po Thaung. 2015. An Overview of Higher Education Reform in Myanmar. Paper presented at International Conference on Burma/Myanmar Studies, Burma/Myanmar in Transition: Connectivity, Changes and Challenges, University Academic Service Centre (UNISERV), Chiang Mai, Thailand, July 24–25. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Alfred M., and John N. Hawkins, eds. 2018. Massification of Higher Education in Asia: Consequences, Policy Responses and Changing Governance. Higher Education in Asia: Quality, Excellence and Governance. Singapore: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ximenes, Pedro Barreto. 2024. Higher Education in Timor-Leste. In International Handbook on Education in South East Asia. Edited by Lorraine Pe Symaco and Martin Hayden. Springer International Handbooks of Education. Singapore: Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Kim Qinzi, Jessica Yi Han Aw, and Collin F Payne. 2024. Inequalities in Mortality in the Asia-Pacific: A Cross-National Comparison of Socioeconomic Gradients. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 79: gbad193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Yiran Vicky, Suman Bhattacharjea, and Benjamin Alcott. 2023. A Slippery Slope: Early Learning and Equity in Rural India. Oxford Review of Education 49: 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Zhiyong. 2010. Higher Education Access and Equality Among Ethnic Minorities in China. Chinese Education & Society 43: 12–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).