Can I Be Myself Here? LGBTQ+ Teachers in Church of England Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context

Freirean Critical Pedagogy as a Theoretical Lens

1.2. Oppression

1.3. Social Transformation

The role of emotions or the relational side of teaching is central to Freire’s (1996) vision for education.Without certain qualities or virtues, such as a generous loving heart, respect for others, tolerance, humility, a joyful disposition, love of life, openness to what is new, a disposition to welcome change, perseverance in the struggle, a refusal of determinism, a spirit of hope, and openness to justice, progressive pedagogical practice is not possible.

1.3.1. Historical and Policy Context

1.3.2. Workplace Climate and Culture

1.3.3. Identity and Disclosure

1.3.4. To Be or Not to Be ‘Out’

This is clearly a very personal and individual decision and determined by a myriad of contextual issues, such as school climate, ethos, and leadership and staff attitudes, which need to be considered carefully (Hardie 2012), as well as prevailing societal norms and expectations (Lundin 2016; O Brien 2024). Lundin’s (2016) research with Swedish teachers suggests that LGBTQ+ teachers regularly monitor their behaviour in schools, being particularly mindful when speaking about a partner, or sharing about social occasions. Evidence suggests that actively concealing aspects of one’s identity can lead to psychological distress, and, in particular, when trying to conform to perceived heteronormative behaviours, can lead to internalised homophobia and poor self-perception (O Brien 2024; Stones and Glazzard 2019).The choice of a teacher to be “out” in the classroom is perhaps unadvisable, possibly joyous, potentially disastrous, positively political, and just plain hard.

Hardie (2012) proposes that there are five strategies that LGBTQ+ teachers use with relation to their identity: ‘These strategies, on a continuum, are passing, covering, being implicitly out and being explicitly out’ (p. 280). She stresses that ‘these strategies are not mutually exclusive’ (p. 280) and might be used concurrently. She describes passing as where information is shared that suggests that the person might be heterosexual, while covering is how subtle choices of language, such as non-gender-specific pronouns, conceal identifying information (Hardie 2012). Of all of these strategies, which Hardie (2012) claims to have used at different times, she cites being explicitly out as both potentially carrying the most risk, but also the most support: ‘Being out with their [her colleagues] endorsement gave me confidence to be true to myself’ (p. 280). The strategies outlined by Hardie (2012) reflect a negotiation between safety, visibility, and authenticity. The choice is often shaped by perceived risks, including discrimination, loss of respect, or career limitations (Fahie 2016; Stones and Glazzard 2019). These strategies are not static but fluid, influenced by school culture, leadership, and societal norms. Freire’s (1996) concept of conscientização—critical consciousness—offers a lens to understand how teachers resist or conform to these pressures.A discreet, tactful approach such as sharing who my family includes gives queer students a signal that they can choose to acknowledge, while at the same time, because it is simply stated, it conveys that this is normal.

Sometimes silence can be a result of fear rather than choice, and therefore not empowering. In my case, I did not interpret silence as a powerful position to be in, because my silence was the way I kept myself safe, although I wanted to be out and proud.(p. 278)

1.3.5. Pressure and Responsibility to Be a Role Model/Ambassador

1.3.6. Discrimination

1.3.7. Harassment

1.4. Intersectionality

Enabling Flourishing

1.5. Research Rationale and Aims

1.5.1. Research Question

1.5.2. Sub Question

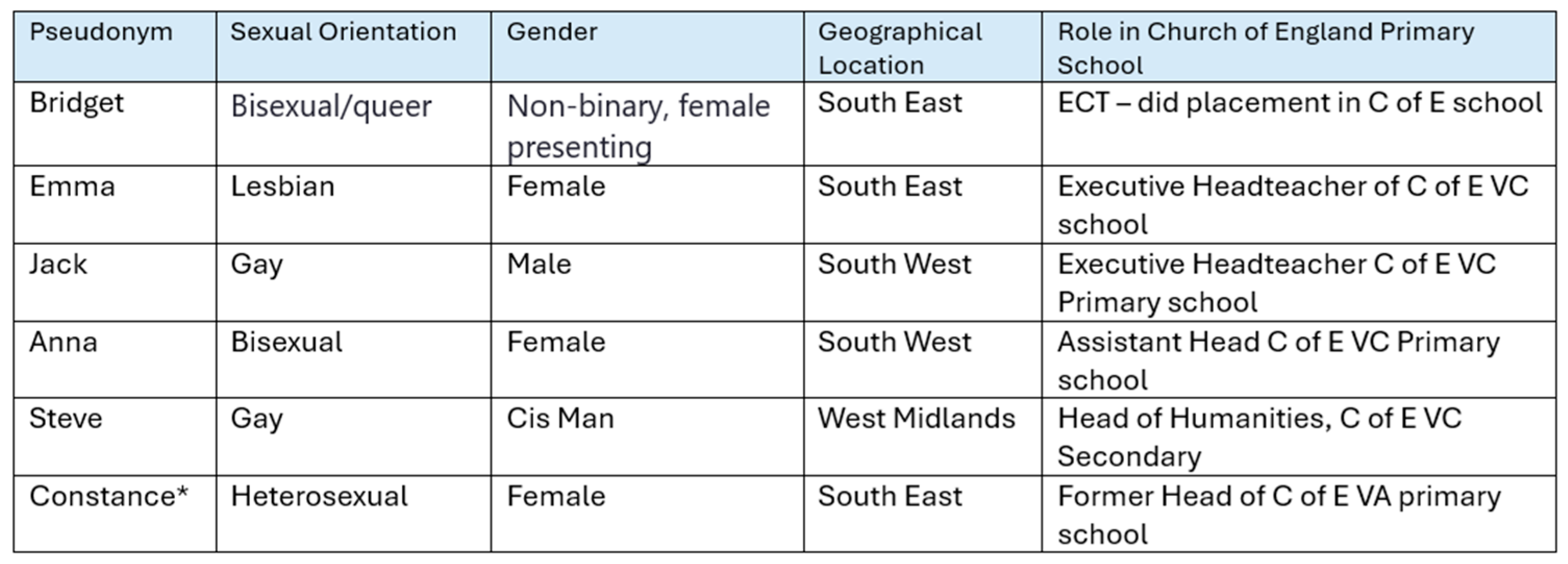

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Researcher Positionality

Engaging in reflexivity is essential to mitigating biases and understanding the impact of research on both participants and researchers. This involves continuous examination of potential influences on data collection and analysis (McDonald 2013), reinforcing ethical research practices in LGBTQ+ studies.Rather than hide behind a false veil of neutrality and disembodiment, we name our identities in relation to our research participants as a means to challenge ourselves and others to define how research projects are necessarily embedded within researchers’ identities.

2.2. Methods

2.3. Ethics

Analysis of Data

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Theme 1 Personal Identity

3.1.1. Being out or Not

I’m pretty open about who I am and everything with adults linked to the school, and I’ve never had any issues or any reason to feel uncomfortable or unhappy about anything to do with that side of things’.(Jack)

This frustrated her as she said that she would like to be more open, and indeed felt that things are different with children now, and that they seem ‘much more open-minded, there is no longer any taboo.’ This sentiment was echoed by Jack, who felt that in the last five years he had noticed a change in pupils. He said that previously, he would have been careful not to divulge too much information if asked if he was married, for fear that parents might find this inappropriate. Lee (2019, p. 250) cautions that ‘the literature demonstrates overwhelmingly that LGBT teachers still take great care how, and to whom, they reveal their sexuality at work.’ Jack said that he ‘was torn’ as he felt that he was ‘in a position where [he] had a responsibility to be open’ (M. L. Rasmussen 2004; Hardie 2012; Lee 2019)—this sub-theme of responsibility is explored later in more detail—but he shared that he was uneasy, and felt that he should be braver. As we discussed this, Jack stated that he hoped that ‘I might be a little bit braver now if someone was to ask.’ He said that because of the work his school had done around equalities and stereotypes, his hope would be that there would not be ‘that assumption that I would have a wife, you know. But I don’t know that for sure.’ Research suggests that, overwhelmingly, school cultures continue to present a heteronormative narrative (Brett 2024; O Brien 2024; Jacinto et al. 2025). Steve also alluded to this anxiety, stating that although the school seems supportive, hosts an LGBTQ+ club for students, and was supportive of him leading LGBTQ+ assemblies where he would share his personal experience, nevertheless, ‘There’s still always that reservation about revealing my sexuality to certain people, particularly visitors.’ This hesitation is often seen in the literature. Lundin (2016) states that LGBTQ+ teachers spoke of needing to be mindful about what they shared.I’m not really worried about telling the children, but it’s still the parents. I still think, is that going to stand in the way of me making a positive relationship with these people? Is it going to put some barrier in there?

3.1.2. Responsibility to Be a Role Model

Emma did add, however, that she also felt it was a privilege in a way to support other head teachers who were, in turn, trying to support their staff.I think if you are in a minority group and maybe when you are a head teacher or somebody in leadership from that community, you feel that is your responsibility because if you don’t do it, who will? And I know there will be other people, but you can’t really say no sometimes. Well, I don’t feel I can.

3.1.3. Career Confidence

3.2. Theme 2 School Environment

3.2.1. Inclusive Schools

Some of the participants talked about the ways that they actively encouraged inclusion in their schools, which ranged from the provision of reading books with same-sex relationships, displays around the school for Pride, No Outsiders (Moffat 2024) and assemblies focusing on equalities, including in terms of LGBTQ+ and LGBT History Month. Participants also shared how their Personal, Social, Health Education (PSHE) lessons included discussions on every different type of family from a diversity perspective. Ensuring curriculum content is developed to reflect and normalise inclusive practice is seen as a fundamental approach to ensuring inclusive practice (Llewellyn 2024; Marston 2015; van Leent 2017).I feel like it helps me in my own sexuality, in myself, to feel valued because I can talk openly with children about all these other people and that everyone’s working it out in their own way…., it’s not a big thing.

3.2.2. Christian Values

3.2.3. Specific Challenges of Church of England Schools

3.3. Theme 3 Working in Church of England Schools

3.4. Outlier Data

Findings from Constance, an LGBTQ+ Ally

This sudden realisation of the challenges faced by the LGBTQ+ community reflects what Freire (2007, p. 3) calls an ‘awakening to oppression.’ Freire discusses how educators have an ‘ethical responsibility to reveal [and address] situations of oppression’ (2007, p. 3).I [was] absolutely not having any of that. That is the inclusion agenda right there. And I made it my absolute mission that they were absolute equals in the parenting community … I was recruited as an inclusive leader and I absolutely was … and I sort of felt it moving through the school.

However, Constance did reiterate the point made by the other participants about the sense of community and shared values that were part of being in a C of E school: ‘Those shared values come across very powerfully.’ Constance’s takeaway message for LGBT+ teachers concerned about working in a C of E school was to ensure that these conversations are had at interview: ‘You’ve got to talk to the teachers … because that will indicate to you the flexibility, the freedom, the inclusion.’ Specifically discussing ECTs, Constance advised a very direct approach: ‘I’d also say to them, ask outright. Just say... We’ve been talking at university about LGBTQ+, where would you say the school sits in that?’C of E schools very often have a very traditional history, that’s guided by Christian beliefs and values and traditions. There is a sense sometimes of fear about coming away from that, when sometimes things look like they might be challenging the beliefs.

4. Conclusions

4.1. Limitations of This Research

4.2. Key Implications for Practice

- There is a call to action for schools and dioceses to better communicate their inclusivity to prospective staff and student teachers, whether this is through explicit content on their websites and/or interview documentation, or deliberate conversations on pre-visits and in the interview process.

- A key message for dioceses is the need to ensure that specific documentation, such as but not limited to Valuing All God’s Children, is well publicised to all school settings and stakeholders. In particular, Steve, our secondary participant, mentioned that he was not sure what documentation was there to support secondary C of E Schools.

- Diocesan CPD (Primary and Secondary), to support LGBTQ+ leadership, teachers, and wider stakeholders, both for general practice, but also more specifically for when schools might be faced with complaints/challenges from parents.

- Focus on relationships and belonging. The “family feel” described by Steve and the nurturing ethos shared by Anna reflect Freire’s (1996) belief that education is relational. C of E schools must prioritise belonging, not just for students but for their staff too, through leadership that listens and is able to enter into authentic dialogue.

- Church school values (e.g., love, grace, and respect) can become tools for liberation when enacted through inclusive policies and relational leadership. Freire (1996) calls for a move beyond symbolic gestures to transformative practice. A reconsideration of how schools use these values would support school cultures as spaces for dialogue.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agosto, Vonzell, and Ericka Roland. 2018. Intersectionality and educational leadership: A critical review. Review of Research in Education 42: 255–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaawi, Ali. 2014. A Critical Review of Qualitative Interviews. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences 3: 149–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Civil Liberties Union. 2025. Mapping Attacks on LGBTQ Rights in U.S. State Legislatures in 2025. Available online: https://www.aclu.org/legislative-attacks-on-lgbtq-rights-2025 (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brett, Adam. 2024. Under the spotlight: Exploring the challenges and opportunities of being a visible LGBT+ teacher. Sex Education 24: 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breunig, Mary. 2016. Critical and social justice pedagogies in practice. Encyclopaedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory 10: 978–81. [Google Scholar]

- British Education Research Association (BERA). 2024. Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research, 5th ed. London: BERA. Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/ethical-guidelines-for-educational-research-fifth-edition-2024 (accessed on 20 July 2025).

- Center for American Progress. 2025. The LGBTQI+ Community Reported High Rates of Discrimination in 2024. Available online: https://www.americanprogress.org/article/the-lgbtqi-community-reported-high-rates-of-discrimination-in-2024/ (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Clarke, Charles. 2017. Not all Faith Schools are the Same: Recognise the Differences. Available online: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2017/10-february/features/features/not-all-faith-schools-are-the-same-recognise-the-differences (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Collier-Spruel, Lauren A., and Anne Marie Ryan. 2022. Are All Allyship Attempts Helpful? An Investigation of Effective and Ineffective Allyship. Journal of Business Psychology 39: 83–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, Millie. 2025. Doctors weigh in on Supreme Court’s Trans Women Ruling. Available online: https://www.independent.co.uk/bulletin/news/trans-supreme-court-decision-women-doctors-b2741466.html (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Cornwall, Susannah. 2022. Factsheet: Sexuality and the Church of England. Available online: https://religionmediacentre.org.uk/factsheets/sexuality-same-sex-marriage-cofe (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Cumming-Potvin, Wendy. 2023. LGBTQA+ allies and activism: Past, Present and Future Perspectives. Continuum 38: 338–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cutler, Blake. 2022. ‘Just Wear their Hate with Pride’: A Phenomenological Autoethnography of a Gay Beginning Teacher in a Rural School. Sex Education 23: 363–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, Madeline. 2014. Welby Launches Anti-Homophobia Schools Guide. Available online: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2014/9-may/news/uk/welby-launches-anti-homophobia-schools-guide (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Department for Education (DfE). 2023. Gender Questioning Children: Non-Statutory Guidance for Schools and Colleges in England. Available online: https://consult.education.gov.uk/equalities-political-impartiality-anti-bullying-team/gender-questioning-children-proposed-guidance/supporting_documents/Gender%20Questioning%20Children%20%20nonstatutory%20guidance.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Department for Education (DfE). 2024. Draft Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education Statutory Guidance for Governing Bodies, Proprietors, Head Teachers, Principals, Senior Leadership Teams, Teachers. Available online: https://healtheducationresources.unesco.org/library/documents/relationships-education-relationships-and-sex-education-rse-and-health-education (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Department for Education (DfE). 2025. Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education: Statutory Guidance for Governing Bodies, Proprietors, Head Teachers, Principals, Senior Leadership Teams, Teachers. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62cea352e90e071e789ea9bf/Relationships_Education_RSE_and_Health_Education.pdf (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Dreer, Benjamin. 2023. On the outcomes of teacher wellbeing: A systematic review of research. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1205179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyer, Sonya C., and Jennifer L. Buckle. 2009. The Space Between: On Being an Insider-Outsider in Qualitative Research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 8: 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fahie, Declan. 2016. ‘Spectacularly exposed and vulnerable’–how Irish equality legislation subverted the personal and professional security of lesbian, gay and bisexual teachers. Sexualities 19: 393–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferfolja, Tania. 2010. Lesbian teachers, harassment and the workplace. Teaching and Teacher Education 26: 408–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2018. An Introduction to Qualitative Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- For Women Scotland Ltd. v The Scottish Ministers. 2025. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2024-0042 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Freire, Paulo. 1994. Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1996. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, rev ed. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 1998. Pedagogy of Freedom: Ethics, Democracy, and Civic Courage. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Freire, Paulo. 2007. Daring to Dream: Towards a Pedagogy of the Unfinished. Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, Paul, Kate Stewart, Elizabeth Treasure, and Barbara Chadwick. 2008. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: Interviews and focus groups. British Dental Journal 204: 291–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giroux, Henry A. 2010. Rethinking education as the practice of freedom: Paulo Freire and the promise of critical pedagogy. Policy Futures in Education 8: 715–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guijarro-Ojeda, Juan Ramón, Raúl Ruiz-Cecilia, Manuel Jesús Cardoso-Pulido, and Leopoldo Medina-Sánchez. 2021. Examining the interplay between queerness and teacher wellbeing: A qualitative study based on foreign language teacher trainers. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 12208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gust, Scott. 2007. “Look out for the football players and the frat boys”: Autoethnographic reflections of a gay teacher in a gay curricular experience. Educational Studies 41: 43–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hankivsky, Olena, and Renee Cormier. 2011. Intersectionality and public policy: Some lessons from existing models. Political Research Quarterly 64: 217–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardie, Ann. 2012. Lesbian teachers and students: Issues and dilemmas of being ‘out’ in primary school. Sex Education 12: 273–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harding, Jamie. 2018. Qualitative Data Analysis: From Start to Finish, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Hayfield, Nikki, and Caroline Huxley. 2015. Insider and outsider perspectives: Reflections on researcher identities in research with lesbian and bisexual women. Qualitative Research in Psychology 12: 91–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, Ji, Dionne Cross Francis, Casey Haskins, Kelly Chong, Kathryn Habib, Weverton Ataide Pinheiro, Sarah Noon, and Jessica Dickinson. 2024. Wellbeing under threat: Multiply marginalized and underrepresented teachers’ intersecting identities. Teachers and Teaching 30: 762–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, Cal. 2023. Institutional cisnormativity and educational injustice: Trans children’s experiences in primary and early secondary education in the UK. British Journal of Educational Psychology 93: 73–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas-Abril, Cristina A., and Francisco Javier Palacios-Hidalgo. 2022. LGBTIQ+ issues in teacher education: A study of Spanish pre-service teachers’ attitudes. Teachers and Teaching 28: 461–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, Rebecca. 2024. Withdrawal of Valuing All God’s Children. Available online: https://www.churchofengland.org/sites/default/files/2025-01/valuing-all-gods-children-24-01-2025.pdf (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- International Bar Association. 2024. Fears of Erosion of LGBTQI+ Rights in Multiple Western Countries. Available online: https://www.ibanet.org/fears-of-erosion-of-lgbtqi-rights-in-multiple-western-countries (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- Jacinto, Juan Gabriel I., Janine Ysabelle C. Odulio, Sabine Dominique B. Sison, and Ma Elizabeth J. Macapagal. 2025. Through the eye of a needle: Understanding the identities of LGBTQ+ teachers within Catholic institutions in the Philippines. Journal of Homosexuality 72: 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohan, Walter O. 2019. Paulo Freire and the Value of Equality in Education. Educação e Pesquisa 45: e201600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristie Higgs v Farmor’s School. 2025. EWCA Civ 109. Available online: https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/uksc-2025-0040 (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Lawford-Smith, Holy, and William Tuckwell. 2024. What is an ally? Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Catherine. 2019. How do Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Teachers Experience UK Rural School Communities? Social Sciences 8: 249–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, Sam. 2019. Compton’s Cafeteria Riot: A historic act of Trans Resistance, Three Years before Stonewall. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2019/jun/21/stonewall-san-francisco-riot-tenderloin-neighborhood-trans-women (accessed on 25 January 2024).

- Levy, Denise L. 2013. On the outside looking in? The experience of being a straight, cisgender qualitative researcher. Journal of Gay and Lesbian Social Services 25: 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lineback, Sally, Molly Allender, Rachel Gaines, Christopher J. McCarthy, and Andrea Butler. 2016. “They Think I Am a Pervert:“ A Qualitative Analysis of Lesbian and Gay Teachers’ Experiences With Stress at School. Educational Studies 52: 592–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llewellyn, Anna. 2024. Bursting the ‘childhood bubble’: Reframing discourses of LGBTQ+ teachers and their students. Sport, Education and Society 29: 622–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundin, Mattias. 2016. Homo-and bisexual teachers’ ways of relating to the heteronorm. International Journal of Educational Research 75: 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrs, Sarah A., and A. Renee Staton. 2016. Negotiating difficult decisions: Coming out versus passing in the workplace. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counselling 10: 40–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, Kate. 2015. Beyond bullying: The limitations of homophobic and transphobic bullying interventions for affirming lesbian, gay, bisexual and trans (LGBT) equality in education. Pastoral Care in Education 33: 161–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonald, James. 2013. Coming out in the field: A queer reflexive account of shifting researcher identity. Management Learning 44: 127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLaren, Peter. 1999. Research news and comment: A pedagogy of possibility: Reflecting upon Paulo Freire’s politics of education: In memory of Paulo Freire. Educational Researcher 28: 49–56. [Google Scholar]

- Mizzi, Robert C. 2016. Heteroprofessionalism. In Critical Concepts in Queer Studies and Education. Edited by N. M. Rodriguez, W. J. Martino, J. C. Ingrey and E. Brockenbrough. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 137–47. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Andrew. 2024. No Outsiders: We Belong Here. London: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Mortari, Luigina, and Deborah Harcourt. 2012. ‘Living’ ethical dilemmas for researchers when researching with children. International Journal of Early Years Education 20: 234–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Society for Education. 2025. Flourishing for All: Inclusion Guidance for Church of England Schools. Available online: https://www.nse.org.uk/curriculum-and-inclusion/inclusion-flourishing-for-all (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- O Brien, Trevor. 2024. LGBT+ Teachers in Ireland’s Experiences in Primary Schools. Sex Education, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Ozanne Foundation. n.d. Background to Charity. Available online: https://ozanne.foundation/background-to-charity/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Rasmussen, David. 2012. Critical Theory. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy 26: 291–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Mary Lou. 2004. The problem of coming out. Theory Into Practice 43: 144–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Røthing, Åse. 2008. Homotolerance and heteronormativity in Norwegian classrooms. Gender and Education 20: 253–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin-Baden, Maggi, and Claire Major. 2013. Qualitative Research: The Essential Guide to Theory and Practice. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Stones, Samuel, and Jonathan Glazzard. 2019. The experiences of Teachers who Identify as Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender or Queer (LGBTQ+). Available online: https://www.bera.ac.uk/blog/the-experiences-of-teachers-who-identify-as-lesbian-gay- (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- The Church of England. 2024. Flourishing for All. Available online: https://www.churchofengland.org/about/education-and-schools/education-publications/anti-bullying-guidance-church-england-schools (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- The Church of England. n.d. Living in Love and Faith. Available online: https://www.churchofengland.org/resources/living-love-and-faith (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- The Church of England Education Office. 2019. Valuing All God’s Children Guidance for Church of England Schools on Challenging Homophobic, Biphobic and Transphobic Bullying. London: The Church of England Education Office. [Google Scholar]

- The Education Act. 1944. Available at Education Act 1944 (repealed 1.11.1996). Available online: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/7-8/31/contents (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- The Good Law Project. 2025. Help Us Challenge the Supreme Court’s Judgement on Trans Rights. Available online: https://goodlawproject.org/crowdfunder/supreme-court-human-rights-for-trans-people/ (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- The International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Intersex Association (ILGA) World. 2024. #RenewIESOGI: Global Civil Society Statement at the Human Rights Council. ILGA World. Available online: https://ilga.org/news/renewiesogi-hrc59-global-statement (accessed on 7 July 2025).

- The National Society. n.d. Our History. Available online: https://www.nse.org.uk/about/our-history (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- The National Society for Education. 2025. Flourishing for All: Anti-Bullying Guidance for Church of England Schools September 2024 (amended April 2025). Available online: https://cofefoundation.contentfiles.net/media/assets/file/FFA_Slide_deck_September_2024_new_branding.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2025).

- Toledo, William, and Bridget Maher. 2021. On becoming an LGBTQ+-identifying teacher: A year-long study of two gay and lesbian preservice elementary teachers. Journal of Homosexuality 68: 1609–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tymms, Peter. 2021. Questionnaires. In Research Methods and Methodologies in Education. Edited by Robert Coe, Michael Waring, Larry V. Hedges and Laura Day Ashley. London: Sage, pp. 277–87. [Google Scholar]

- University of Winchester. 2015. Research & Knowledge Exchange Ethics Policy and Procedures. Available online: https://intranet.winchester.ac.uk/information-bank/research-and-knowledge-exchange/Documents/Ethics%20Policy%20and%20Procedures%20_Final%20Sep2015.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- van Leent, Lisa. 2017. Supporting school teachers: Primary teachers’ conceptions of their responses to diverse sexualities. Sex Education 17: 440–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagle, Tina, and David T. Cantaffa. 2008. Working our hyphens: Exploring identity relations in qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry 14: 135–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wharton, Julie, and Rhiannon Love. 2025. Outsider Positionality: Blurring the Boundaries. In The Guide to LGBTQ+ Research. Edited by Adam Brett and Catherine Lee. Leeds: Emerald Publishing, pp. 115–24. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Hattie. 2022. C of E Schools Guidance Defended Against Gender-Transition Criticism. Church Times. Available online: https://www.churchtimes.co.uk/articles/2022/4-november/news/uk/c-of-e-schools-guidance-defended-against-gender-transition-criticism (accessed on 20 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Love, R.; Wharton, J. Can I Be Myself Here? LGBTQ+ Teachers in Church of England Schools. Soc. Sci. 2025, 14, 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100590

Love R, Wharton J. Can I Be Myself Here? LGBTQ+ Teachers in Church of England Schools. Social Sciences. 2025; 14(10):590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100590

Chicago/Turabian StyleLove, Rhiannon, and Julie Wharton. 2025. "Can I Be Myself Here? LGBTQ+ Teachers in Church of England Schools" Social Sciences 14, no. 10: 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100590

APA StyleLove, R., & Wharton, J. (2025). Can I Be Myself Here? LGBTQ+ Teachers in Church of England Schools. Social Sciences, 14(10), 590. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci14100590