Abstract

Social media has evolved into a central force in handling national and local crises. This prompts the question: Do all stakeholders in a local crisis grasp its significance when it predominantly unfolds in the digital realm of online social media? This article investigates this issue through a case study of the Roman Zadorov justice movement in Israel. Despite Zadorov’s wrongful imprisonment for Tair Rada’s murder, social media support grew, reshaping perceptions of Katsrin, the town where the murder took place. The four-fold analysis draws on social media content, youth interviews, municipal officials’ perspectives, and a population survey. It reveals how Tair Rada’s case became central to Katsrin’s image, fueled by social media’s influence. However, local officials failed to recognize social media’s crisis significance, highlighting a disconnect. The article concludes by exploring this dissonance, shedding light on crisis management challenges in the social media era and their impact on local governance.

1. Introduction

In the digital age, social media has become a primary space where public perceptions are shaped, contested, and amplified. This transformation has far-reaching implications for how places are perceived and how reputational crises emerge and evolve. Yet, when such crises unfold predominantly online—without physical manifestations or immediate administrative disruptions—they may be overlooked by those tasked with responding to them.

This article investigates a critical and underexplored phenomenon: the disconnect between public recognition of a reputational crisis and its dismissal by local decision-makers. Using the case of Katsrin, a small town in northern Israel, the study examines how the long-standing public discourse around the 2006 murder of Tair Rada—and the subsequent wrongful conviction of Roman Zadorov—has significantly shaped the town’s image in digital spaces. The findings of this study demonstrate that despite widespread online engagement and a sustained negative portrayal of the town, local authorities largely perceive the situation as a non-crisis and unworthy of strategic intervention.

Image crises, by definition, involve serious damage to the public perception of a person, organization, or place. They can have profound effects on public trust, stakeholder relationships, and socio-economic well-being. Crisis management literature emphasizes the need for timely recognition, transparent communication, and active engagement in such moments. However, in the case examined here, a reputational crisis exists without formal acknowledgment—raising important theoretical and practical questions about crisis recognition in the digital era.

While growing research addresses municipal use of social media and citizen-driven digital activism, the specific issue of local image crises on social media—and their (mis)recognition by authorities—remains largely unexplored. This study fills that gap. It employs a multi-method approach, including a national survey, interviews with local youth and officials, and a netnographic analysis of social media content related to the Zadorov case. Together, these sources offer a layered understanding of how a place can become symbolically stigmatized in online discourse and how such narratives may persist, even in the absence of local institutional response.

By bringing attention to the “unrecognized crisis” at the municipal level, this article contributes to ongoing conversations in crisis communication, place branding, and digital public engagement. It argues that digital narratives—particularly when widely circulated and emotionally resonant—can pose significant reputational risks. Institutional failure to acknowledgie them may exacerbate alienation, distrust, and long-term harm to a community’s image.

2. Digital Reputation Crises in Local Communities

The perception of a place’s image encompasses “the amalgamation of beliefs, ideals, and impressions that people hold regarding a specific location.” (Kotler et al. 1993, p. 3). There are several classifications of place images: positive, negative (typically linked to crime, economic and social hardships, violence, security challenges, etc.), contradictory (where one audience perceives the place positively while another views it negatively), mixed (positive in certain aspects and negative in others), and weak (referring to places that are relatively unknown with minimal available information) (Kotler et al. 1993). Another pertinent distinction distinguishes between a rich image, associated with well-known locales with ample available information, and a poor image, which pertains to less-known localities, primarily relying on external sources for information (Avraham 2003).

Place branding is a strategic approach to managing a location’s image, particularly crucial for places facing crises or negative perceptions. Avraham and Ketter’s research propose a multi-step model for altering place images and emphasize the importance of holistic, long-term approaches rather than quick fixes. Strategies range from ignoring crises to actively countering stereotypes, hosting events, and leveraging celebrities or media (Avraham and Ketter 2012, 2016). Jones and Kubacki’s review confirms that place branding can be successful for locations with social problems, but it requires comprehensive efforts beyond mere promotion (Jones and Kubacki 2014). The research underscores the complexity of place branding, especially for destinations with negative images, and the need for tailored, multifaceted strategies to effectively reshape public perceptions.

Furthermore, Avraham’s insights into place branding emphasize the need for local authorities to acknowledge and address the reputational crises actively. By understanding the impact of digital narratives on public perception, officials can develop more effective strategies to counter negative portrayals and highlight the town’s strengths.

Crisis management at the local level encapsulates a comprehensive set of strategies and processes that local governments and agencies implement to prepare for, respond to, recover from, and mitigate crises. This holistic approach, as described by Kapucu (2008), emphasizes the necessity of a multi-phase structure that includes mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery—a model known as the Comprehensive Emergency Management Model (CEMM). The mitigation phase focuses on reducing the risk of crises occurring, while the preparedness phase involves planning and training to ensure an effective response. Once a crisis unfolds, the response phase is activated, mobilizing the necessary resources and services to address the immediate needs. Lastly, the recovery phase seeks to restore the community’s functionality and infrastructure.

In addition to structured command systems, the theory of Community-Based Disaster Management (CBDM) posits that the active involvement of the community is paramount for effective crisis management. According to Allen (2006), integrating local knowledge and capacities into planning and decision-making processes enhances the community’s resilience to disasters and crises. The synthesis of these theories and practices underscores the critical role of local authorities in navigating the complex landscape of crisis management. By harnessing a combination of well-structured command systems and community-based approaches, local bodies are better positioned to address the multifaceted challenges presented by crises.

The crises previously discussed increasingly find their way onto social media platforms, profoundly affecting the local discourse. A significant portion of societal, political, and cultural dialogue has transitioned to social media, and this is also true for conversations about places. Unlike traditional media such as radio or television, where content is transient, information on the Internet and social media is persistent, remaining accessible indefinitely. This can lead to widespread dissemination, potentially exacerbating and prolonging a local crisis due to the media’s characteristics.

Jin et al. (2014) discuss the role of social media in crisis management, highlighting how the origin of information, its form, and its source can significantly influence public responses to a crisis. This is particularly relevant to local crises, where social media can both amplify and sustain the negative portrayal of places.

The use of social media during disasters is a growing area of research, with platforms like Twitter being identified as critical tools for communication during such times. According to surveys (Saroj and Pal 2020), social media’s role in disaster scenarios is significant, as reported in the literature from 2007 to 2019. The term ‘crisis informatics’ has been used to describe the role of social media in crisis communication, emphasizing its importance in enabling dialogue between the public and authorities.

3. A Crisis, or Not a Crisis?

What makes the current case study particularly intriguing is the paradox it presents. The very individuals responsible for crisis management, fully aware of the online discourse surrounding their town, do not perceive it as a crisis nor see any need for intervention, whereas the general public suggests otherwise. This is, in essence, a crisis disguised as a non-crisis.

In the field of organizational crisis management, there is a well-documented phenomenon where decision-makers fail to recognize an emerging crisis despite clear external warning signs. Known as “crisis conception,” this disconnect highlights a gap between organizational leaders’ perceptions and the objective reality of potential threats. Turner (1976) first introduced this concept, examining how organizations often overlook or misinterpret warning signs due to cognitive biases or institutional norms, resulting in inadequate preparation and response.

Subsequent research has further explored the psychological and structural factors underpinning crisis conception. Weick (1988) emphasized the role of cognitive framing, arguing that the way leaders interpret situations directly influences their perception of risk. When decision-makers approach potential crises with overconfidence or a sense of routine, they are less likely to recognize warning signals, even in the face of contradictory evidence. Pauchant and Mitroff (1992) extended this discussion by highlighting the role of organizational culture. They found that environments discouraging the acknowledgment of vulnerabilities or dissent are particularly prone to crisis conception, as they foster a culture in which warning signs are dismissed or rationalized away.

Decision-makers’ failure to recognize emerging crises—a phenomenon termed crisis conception (Turner 1976; Weick 1988)—can be exacerbated by the unique affordances of digital media. Unlike traditional broadcast media, online content is persistent, remaining accessible and searchable indefinitely, which prolongs public engagement and reinforces negative associations (Saroj and Pal 2020). Social media platforms also enable replicability and rapid circulation, allowing content to be shared widely and repeatedly, thus escalating minor incidents into crises in the public eye (Jin et al. 2014). In addition, the high degree of public participation afforded by digital platforms means that ordinary citizens can frame events collectively, produce user-generated evidence, and sustain emotionally charged narratives that may diverge sharply from official accounts (Coombs and Holladay 2012). These affordances contribute to significant perception gaps: while the public may construct a sustained crisis narrative online, institutions often fail to acknowledge or engage with it, thereby intensifying reputational risks (Boin et al. 2020).

4. Research Environment: Online Activism Calling for Justice for Roman Zadorov

Katsrin is situated at the heart of the Golan Heights, commanding picturesque views of Mount Hermon, the Sea of Galilee, and the Galilee mountains. Its establishment was initiated in the aftermath of the Yom Kippur War, following a government decision in November 1973, which aimed to create an urban center in the Golan. According to the original urban planning, Katsrin was envisioned to accommodate between 20,000 and 30,000 residents within several decades. However, as of 2022, the population of Katsrin numbered only around 8500 residents (Heitner 2019).

Situated in an appealing tourist environment, coupled with meticulous urban planning and sustained investments, Katsrin has garnered recognition over the years as the most well-maintained towns in Israel, earning it the prestigious environmental accolade. Today, Katsrin boasts a variety of educational institutions, The industrial area houses prominent businesses such as the Golan Heights wineries. Katsrin also offers numerous bed and breakfast accommodations and a field school.

On 6 December 2006, 13-year-old Tair Rada was found murdered in her school in Katsrin. Roman Zadorov, a flooring contractor working on the premises, was taken into custody six days afterward. Within a week he admitted to the crime, but soon withdrew his confession and has since consistently denied involvement. In 2010, he was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. The court described the case as resting on a “high-quality, dense and real fabric of evidence,” highlighting Zadorov’s statements to both a police informant and investigators, along with his participation in a reconstruction of the crime. His 2015 appeal to the Supreme Court was dismissed.

Despite the decisive tone of the court’s judgment, public sentiment has consistently diverged, with repeated surveys indicating that large majorities believe Zadorov to be innocent. In 2021, the Supreme Court ordered a retrial, which culminated in his full acquittal in March 2023 (Lev-On 2023b).

Given the focus of this text on Katrzin’s image a decade after the murder, let us begin by briefly examining how the town initially responded to the potential image hazard in the immediate aftermath of the murder. The archival materials depict a tranquil pastoral town that, following the murder, found itself engulfed in a media storm far exceeding its size.

In the wake of the murder, a special effort was made to nurture the image of the town following the murder: For example, the town’s chief rabbi, Yossi Levy, stated in a town meeting shortly after the murder: “Every effort must be made to uphold the city’s good reputation, and everyone should be engaged in this endeavor. Katsrin should not be linked to an image of violence, and phrases like “the writing was on the wall” are not the suitable and fitting descriptions for our city. The educational achievements in Katsrin are significant and should be prominently acknowledged. We are not a community frequented by criminals.” (Lev-On 2023b).

The murder immediately drew widespread public attention, largely because the victim was a young girl killed within the supposed safety of her school. One of the first voices to question Roman Zadorov’s guilt was that of Tair Rada’s mother, who, shortly after the reconstruction of the crime, publicly expressed her doubts that he was the true perpetrator. Over time, inconsistencies in Zadorov’s confession and reenactment, together with competing accounts about who might have committed the murder, how it was carried out, and for what reasons, further fueled skepticism.

Unlike most homicide cases, which are typically investigated away from public scrutiny, this case unfolded in a highly visible manner, with investigative materials eventually reaching a wide audience. After Zadorov’s 2010 conviction, his defense files were passed on to the victim’s family and to activists who supported them. Gradually, these materials became available to the general public, including through Facebook groups. Since 2016, a centralized archive of documents has been maintained on the website Truth Today, which continues to publish correspondence, summaries, and files connected to the retrial. Beyond that, several YouTube channels circulate recordings of interrogations, conversations with informants, and crime-scene reconstructions. The case has also inspired multiple documentaries and journalistic reports accessible online.

A further reason for the extraordinary public engagement with the case has been the vigorous social media campaigning on behalf of Zadorov’s innocence. Beginning in 2009, numerous Facebook groups dedicated to the affair were launched. Following the rejection of Zadorov’s Supreme Court appeal in 2015, the largest of these—The Whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada—expanded to become one of Israel’s biggest online communities (Ben-Israel 2016).

Beyond its sheer scale, this wave of social media activism is unusual in several respects.

- Context: The activity revolves around a criminal trial and a campaign against what supporters regard as a wrongful conviction. Normally, police investigative materials and judicial processes remain largely inaccessible to the broader public.

- Participants’ identity: Public discussions about law and justice are usually dominated by “insiders,” such as attorneys, law enforcement officials, or legal analysts. In this case, however, the discourse was shaped to a large extent by “outsiders”—activists and ordinary citizens who engaged with both major controversies and minor details.

- Impact: The campaign is remarkable for its tangible influence, particularly in shaping public perceptions—both of the performance of state institutions and of Zadorov’s culpability or innocence (Lev-On 2023a, 2023b).

Moreover, this mobilization is distinctive in producing numerous findings by activists—some of which directly contributed to the Supreme Court’s decision to authorize a retrial (Lev-On 2024). Taken together, these elements make the campaign surrounding Zadorov a compelling case study for exploring the dynamics and consequences of social media–driven activism.

5. Methods

Data collection for the current study was conducted more than a decade after the murder, using multiple methodologies that will be detailed later:

- A survey was conducted to assess Katsrin’s image as perceived by the general public.

- This was followed by an analysis of content posted on social media platforms.

- Subsequently, interviews were carried out with Katsrin’s adolescent residents. These young individuals testified to the town’s negative image and were also queried about the role social media plays in shaping this perception.

- Further, the research extended to the perspective of decision-makers through a series of interviews.

This multifaceted research approach was meticulously designed to construct as comprehensive a picture as possible regarding social media crises—the forms they take, and how they are perceived and handled by those in positions of authority.

By dissecting these varied dimensions, the study endeavors to present a holistic view of the crisis landscape within social media. It examines the interplay between public sentiment, the lived experience of the town’s younger population, and the strategic considerations of local governance. This thorough examination provides a basis for understanding the complex dynamics of crisis management in the digital age, particularly as they pertain to local communities grappling with the aftermath of significant events.

The rest of the text relies on four different studies:

- The first study, Katsrin’s Image in the Eyes of the Public a Decade After the Murder utilized a survey conducted in November 2018. Participants were prompted to spontaneously list their associations with Katsrin, providing a platform for unfiltered expressions of thoughts and thereby enhancing the study’s validity (Study 1).

- How is Katsrin Represented in the social media activity for Justice for Zadorov? constituted a netnographic study spanning seven years. This involved employing content analysis of Facebook posts and comments to unravel how Katsrin is portrayed in online discussions within the context of the pursuit of justice for Zadorov (Study 2).

- The third study delved into How Youth from Katsrin Perceive the Image of the Town and What Role Social Media Plays. This investigation relied on telephone interviews with young individuals, centering on their perceptions of Katsrin’s image and the influence of media in shaping it (Study 3).

- Lastly, the fourth study scrutinized Perspectives of Decision-Makers on Katsrin’s Image and the Influence of Social Media. This entailed conducting interviews with officials actively engaged in addressing the Zadorov affair and its aftermath. The focus was on gaining insights into decision-makers’ perspectives on Katsrin’s image and its repercussions, as well as the role of social media in shaping these perceptions (Study 4).

Given that these studies employ different methods and investigate slightly varied research questions, I have chosen to structure the article into four distinct sections. Each section corresponds to one of the studies, providing a detailed review of both the methodology and findings.

6. Findings

6.1. Study 1: Katsrin’s Image in the Eyes of the Public a Decade After the Murder

In a survey conducted in November 2018 through the survey institute iPanel, Israel’s largest online survey company participants were requested to list up to three associations that immediately came to mind when they thought of Katsrin. The survey was conducted among a representative sample of 503 adult respondents across Israel. The sample was stratified to reflect key demographic variables such as age, gender, region, and religiosity, ensuring national representativeness.

In the survey, participants were requested to list up to three associations that immediately came to mind when they thought of Katsrin (like: “beautiful place”, “place where Tair Rada was murdered”, “place in northern Israel”, etc.) The associations were freely typed by participants, not chosen from a pre-determined list. This method offers the advantage of allowing respondents to freely express their thoughts without being constrained by predefined answer categories. This enhances the survey’s validity, as it does not lead respondents toward specific responses they may not have independently considered. To avoid biases, the subjects were asked not only about Katsrin but about other places in Israel, in this order: Afula, Tel Aviv, Katsrin, Jerusalem, Hebron, Be’er Sheva.

As mentioned, respondents were allowed to provide up to three associations. Out of all the respondents, 503 respondents contributed one association, while 305 provided two associations, and 149 respondents offered three associations. If one of the respondents referred to the same category more than once, only one answer was counted in relation to that category. Some of the answers were cataloged in more than one category.

The answers were cataloged by two experienced coders. To better interpret the findings, we follow Avraham’s (2003) typology of place image categories, which distinguishes between “poor” images—general, low-information associations—and “rich” images—specific, value-laden, or emotionally charged associations. Based on participants’ open responses, each answer was coded into one of 14 categories. Of these, three were classified as “poor” and eleven as “rich.”

Based on these responses, 14 distinct categories were constructed. The first three categories were classified as “poor” image types and related primarily to general geographic or typological information:

- Geographic location (e.g., “in northern Israel”)

- Region in Israel (“the Golan Heights”)

- Type of locality (e.g., “a city in Israel”)

The remaining 11 categories were considered “rich” and included more descriptive or value-laden associations:

- References to the murder of Tair Rada and Roman Zadorov

- Agriculture (“green”).

- Tourism-related terms (e.g., “B&Bs,” “vacation”)

- Peripheral aspects (“periphery,” “remote”)

- Specific places within Katsrin (“Golan Brewery”)

- Positive descriptors (“gorgeous view”)

- Negative connotations (“dangerous”, “corruption”)

- Education

- Weather (“cold and rainy”)

- Military-related terms

- Other

The findings demonstrates that the most prevalent image categories associated with the city fall into the “poor” image classification: region in Israel (162), geographic location (155), and type of town (106).

Among the “rich” image categories, the most prominent was the association between Katsrin and the murder of Tair Rada (123). Following that, the “rich” categories in the list included references to Katsrin’s peripheral location (113), mentions of specific places within the town (79), positive descriptors (48), and tourism-related terms (46).

As noted, within the “rich” image categories, the most prevalent association was between Katsrin and the Tair murder case. Approximately a quarter of all respondents made reference to the Tair Rada murder in their responses, using phrases such as Tair Rada, murder, Tair case, murdered girl, and related terms. Interestingly, very few respondents associated Roman Zadorov with Katsrin when asked about the city. This indicates that people strongly link Tair’s murder with Katsrin, more so than they do with aspects like tourism, agriculture, education, and others.

6.2. Study 2: How Is Katsrin Represented in the Social Media Activity for Justice for Zadorov?

The second study is based on a content analysis of posts from the largest Facebook group dedicated to the campaign for justice for Roman Zadorov, covering the period from its establishment until the rejection of Zadorov’s appeal to the Supreme Court. For this purpose, I used NetVizz software to download all posts published in the group and extracted approximately 100 posts containing the word ‘Katsrin’ (see Lev-On and Steinfeld 2020). Only posts were analyzed—rather than comments—because posts are more prominently visible to group visitors and more likely to reflect the group’s overall tone and priorities, as they remain online with the implicit approval of group administrators. These posts were independently coded by the principal investigator and two trained moderators. Themes were identified through repeated close readings by the three coders, achieving 95% inter-coder agreement to ensure consistency and reliability. These procedures contribute to the overall robustness and validity of the findings.

Although the analysis is based on public Facebook content, it is important to acknowledge that such data may reflect the voices of highly active users rather than a representative public. Nevertheless, given the volume, longevity, and consistency of the discourse across multiple groups, we believe the findings offer valid and valuable insight into the online construction of Katsrin’s image.

The findings were organized into three main themes reflecting dominant portrayals of Katsrin within the Facebook discourse. The analysis shows that while many posts mention Katsrin in a neutral manner—primarily as the location where the murder occurred—there are also recurring references to three dominant themes: (1) Katsrin as a town marked by fear and silencing; (2) perceived cover-up and institutional complicity; and (3) national stigma and long-term reputational damage.

6.2.1. Theme 1: Katsrin as a Town Marked by Fear and Silencing

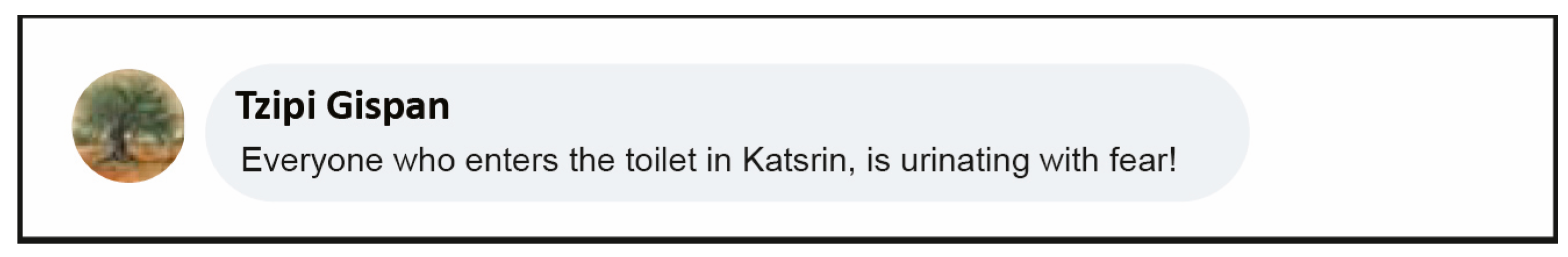

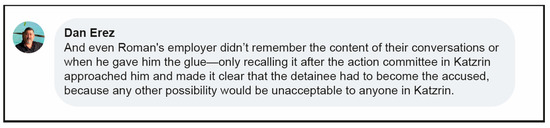

A recurring motif in the online discussions was that Katsrin is a place where residents live in fear and avoid talking about the murder. This fear is described not only as psychological but also as socially enforced silence. This imagery extended even to mundane aspects of life in the town. For example, Tzipi Gispan commented that “everyone who enters the toilet in Katsrin, is urinating with fear!” (Figure 1, referencing the fact that the murder took place in the restrooms).

Figure 1.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 25 April 2016.

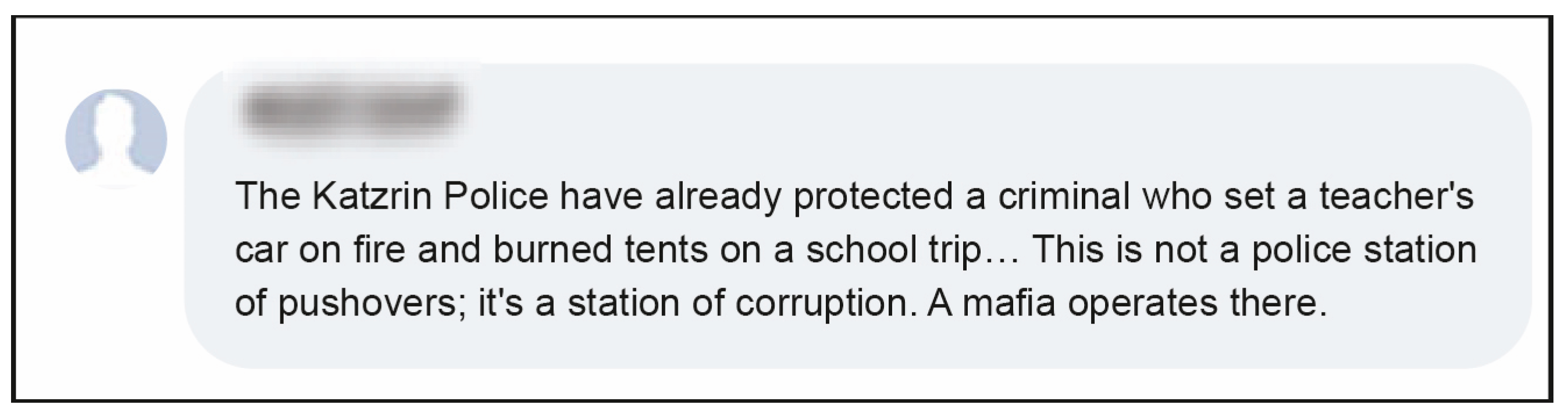

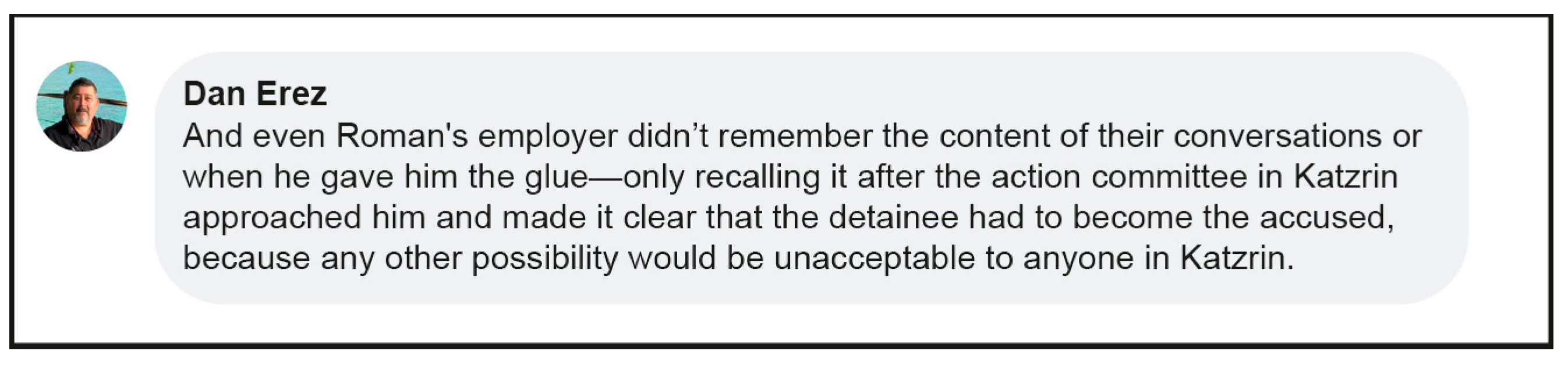

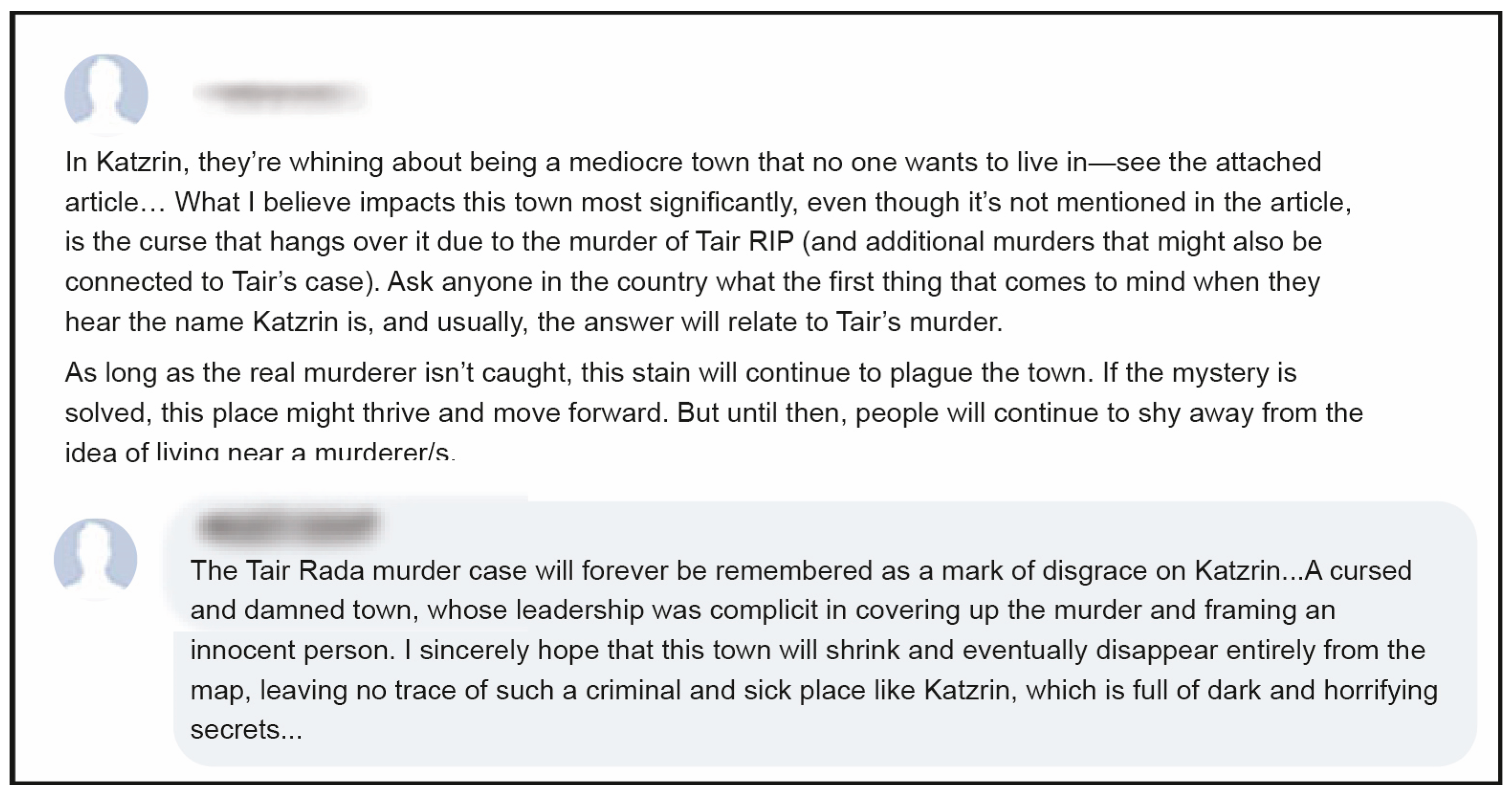

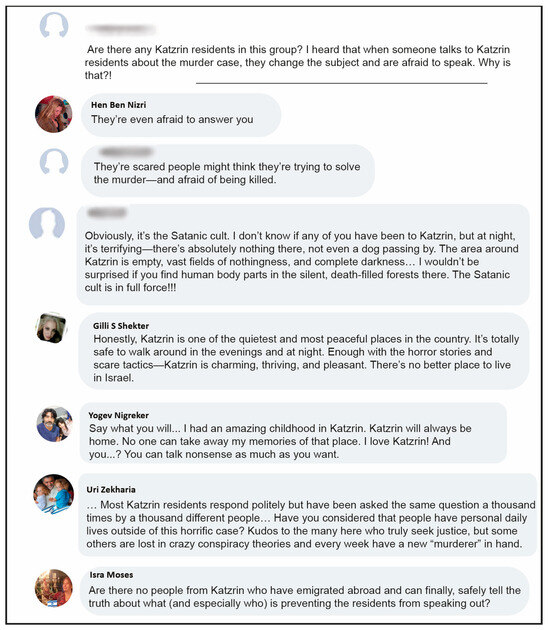

According to other writers, the source of the fear that dominates the town lies in part with the Katsrin police, and they note several cases of controversial behavior by policemen from the Katsrin station (Figure 2). Others argue that the climate of fear was dominant in Katsrin even back when Tair was murdered. They falsely argue that “the action committee” in Katsrin influenced witnesses to change their testimony to the police and demanded that Zadorov’s employer lie in order to establish Zadorov’s conviction and hide the identity of the real killer (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 2016.

Figure 3.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 2016.

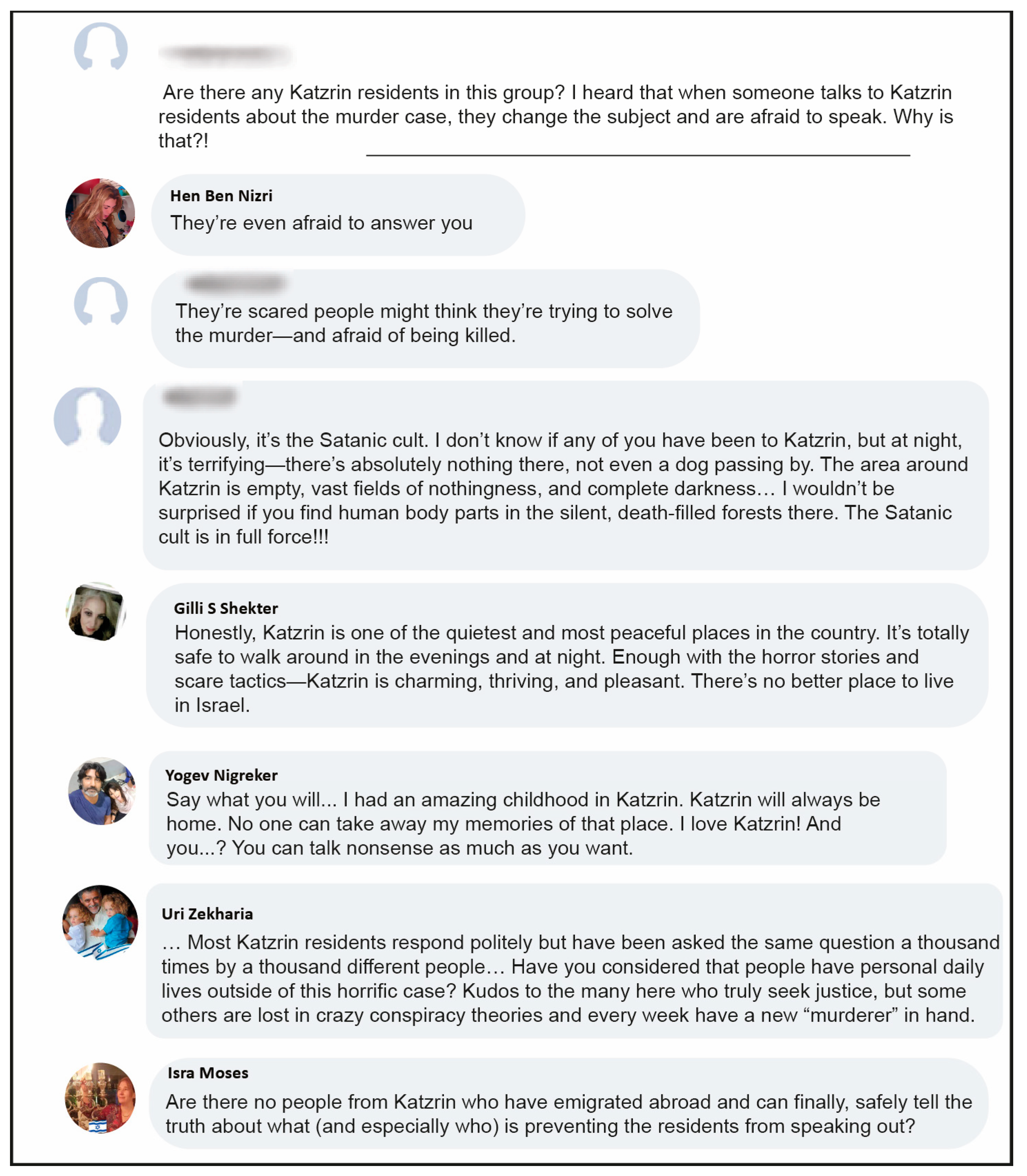

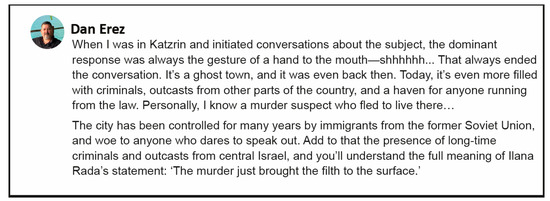

From time to time, Katsrin residents respond to such criticisms of the town. For example, in response to the question, “Are there any Katsrin residents in the group?” I heard that when you talk to them about the murder case, they change the subject and are afraid to talk” (Figure 4), one respondent mentioned that Katsrin residents fear speaking out because they are “afraid for their lives.” Isra Moses suggested a review group website where former Katsrin residents who left the country can openly share what “keeps current residents from speaking the truth.” However, Katsrin residents who defended the town also joined the discussion. Yogev Nigarkar, a prominent activist who also managed Ilana Rada’s Facebook page, stated, “I had an amazing childhood in Katsrin… You can talk nonsense as much as you want.” Uri Zakaria, formerly the deputy head of the council, explained that residents of Katsrin might change the subject or avoid discussing the murder case because they have grown weary of being constantly confronted with the topic after many years.

Figure 4.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 17 December 2018.

6.2.2. Theme 2: Perceived Cover-Up and Institutional Complicity

Another dominant theme in the discourse was the perception that powerful institutions—ranging from local authorities to the police and judiciary—had deliberately suppressed the truth to protect Katsrin’s reputation. According to these narratives, the murder case was not only mishandled but actively covered up by a network of actors with shared interests.

One widely circulated claim pointed to a coordinated effort among officials: “Policemen, judges… mayor, connected parents, school—everyone who lied together in this case did not want to destroy the city of Katsrin. They acted together to protect the town’s image even if it meant framing someone innocent.” Some posts identified specific individuals allegedly connected to powerful figures. For example: “One of those involved is the son of a strong police officer in Katsrin…”

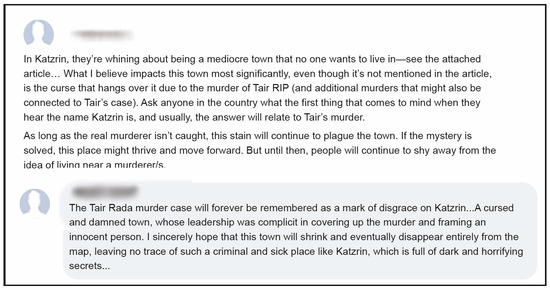

A number of participants framed Katsrin as a town “controlled by criminals.” Dan Erez, a former police officer and one of the group administrators, wrote: “Katsrin is under the control of criminals. It has become a sanctuary for anyone evading the law.” (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 2016.

These posts portray Katsrin not only as a town affected by a single traumatic event, but as a community in which institutional power was allegedly mobilized to distort the legal process for the sake of reputation management.

6.2.3. Theme 3: National Stigma and Long-Term Perception

Beyond the local narratives of fear and concealment, many posts reflected a broader sense of national stigma attached to Katsrin. Participants repeatedly described how the town had become synonymous with the murder of Tair Rada, even many years after the event. The murder, according to these accounts, shaped the town’s identity in the eyes of the Israeli public. In one widely shared post, a link to a news article marking Katsrin’s 40th anniversary was used to emphasize the persistence of this association (Figure 6). The author wrote: “The most significant factor negatively impacting Katsrin is the stigma associated with this town following the murder of the late Tair.” He went on to claim that: “When individuals in Israel are asked about Katsrin, the immediate association is often linked to the Tair murder… This stigma will persist until the real perpetrator is found.” The stigma is not only emotional or reputational—it has, according to some posts, tangible consequences for the town’s development. One user noted that: “The association with a murder creates hesitation among people to consider residing near the town.” Adding to this portrayal, a group admin posted: “The town’s leadership was involved in covering up the murder and wrongly accusing an innocent person.”

Figure 6.

Source: The whole Truth about the Murder of the Late Tair Rada, 2 May 2017.

6.3. Study 3: How Youth from Katsrin Perceive the Image of the Town and What Role Social Media Plays?

In addition to examining the public’s perception of Katsrin’s image, I also explored residents’ perspectives of the image attributed to the town, and whether they believe that the content in mainstream media and on social media plays a role in shaping this image.

Note that there are indications that Katsrin residents, particularly the youth, perceive the town’s image as predominantly negative. This perception is highlighted in a column written by Aviv Tutia (2016), a close friend of Tair, on the tenth anniversary of the murder. He reflected: “During my time in the army and on a trip to South America, I met many people. Everyone asked about my hometown in Israel, and there wasn’t a single person who didn’t say: “Ah, where Tair Rada was murdered.””

To determine if Tutia’s sentiments are echoed by other residents of Katsrin and whether they attribute the media’s role in shaping this perception, I conducted brief telephone interviews with 30 young individuals within Tair’s age group (aged 20–30 at the time of the interviews). The interviewees were selected using a snowball sampling technique. The goal was to reach young adults who had lived in Katsrin around the time of the murder and belonged to the same age cohort as Tair Rada. Based on local population estimates, there were approximately 100 individuals in this age group residing in Katsrin at the time. Thirty interviews were conducted, representing a significant portion of this cohort and providing diverse personal insights into perceptions of the town’s image.

I selected interviewees in this age cohort because of their extensive use of social media platforms, unlike older age groups. Additionally, they are more likely to face questions about the Tair murder and the Zadorov case than their older counterparts, primarily due to their proximity in age to Tair at the time of the tragedy.

Several key findings emerged from these interviews:

- Katsrin’s image is perceived as predominantly negative, according to the interviewees. Overwhelmingly, they report that mentioning they are from Katsrin to people outside the Golan region is often met with a negative reaction. As one interviewee aptly put it, “There’s a prevailing negative image of our town beyond the Golan. When I mention where I’m from, I can sense the skepticism in their reactions”.

- The murder plays a central role in shaping this negative image. According to the large majority of interviews, the murder of Tair Rada is overwhelmingly seen as a pivotal factor contributing to this negative image, especially among those who have limited knowledge of Katsrin. The interviewees believe that for many outsiders, the Tair Rada murder is the foremost association with Katsrin. One interviewee expressed this sentiment by stating, “The Tair Rada murder case has led people to view Katsrin as a dangerous place to avoid.” Another interviewee shared, “People immediately inquire, ‘Why do you live there? It’s remote and seems ominous, and who was the murderer?’ It’s rare for them to ask about the location or what life is like there; the murder always takes center stage”.

- The negative image is attributed to media coverage: Most young people place the responsibility for Katsrin’s negative image on the media’s portrayal of the town over the years. They believe that the media has painted Katsrin as a foreboding, perilous, and enigmatic place where gruesome crimes occur, and this image has persisted. For example, one interviewee stated, “The murder and the way the media portrayed the city as a menacing, shadowy, and enigmatic place have done lasting damage. They tarnished the entire city because of one case. It’s like people don’t even care what the place is actually like anymore—just that it’s “that place where the girl was murdered.””

Another interviewee shared, “I believe the media plays a significant role in creating this negative image. Before the murder, most people didn’t even know Katsrin existed, and since then, the media has continuously covered and mentioned it, always with a negative and critical tone. It’s no surprise that people form these perceptions, as they are constantly exposed to this kind of media coverage on television and in newspapers.” Another interviewee added, “Much of what people think about Katsrin is influenced by the media, both on television and, to a large extent, on the Internet today. It has a significant impact on people’s opinions”.

Some interviewees noted a reduction in negative media coverage of Katsrin over time. One interviewee expressed, “I suppose the media coverage did contribute to some people having negative perceptions about Katsrin. I still come across it from time to time, but I feel that it has decreased as time has passed”.

- 4.

- Regarding the link between the negative image and activity on social media, Beyond the media coverage of Katsrin in general, most interviewees argued that the activity on social networks in particular is a significant factor that affected the image of the town. The majority of respondents emphasized the significant impact of social media activity on Katsrin’s image, as it reaches a broad audience, including people who may not be directly interested in the case but are exposed to its content. One interviewee expressed this sentiment, stating, “In my opinion, social networks carry the most weight in influencing the image.” Another interviewee noted, “Social media activity reaches a wide audience. Even people I encounter in various social circles who are not from Katsrin discuss the Facebook activity. Social networks play a substantial role in disseminating the story and generating a buzz.”

A small number of interviewees believed that social media activity had minimal impact on the settlement’s image. For instance, one interviewee suggested that its primary effect was on the lives of individuals suspected of wrongdoing: “Social media activity reaches a wide audience, making the public feel as if they know everything. It can turn people into amateur detectives, leading to speculations and the invention of stories based on what’s exposed on social media. Still, in terms of the city’s image, I don’t think it has a significant impact, but it does affect how people perceive individuals involved in these events”.

7. Perspectives of Decision-Makers on Katsrin’s Image and the Influence of Social Media

Towards the conclusion of this chapter, I will explore the perspectives of decision-makers. Do they share the belief that Katsrin has a negative image? Do they acknowledge the substantial impact of the murder on the town’s image? Additionally, do they believe that social media activity related to the Zadorov case influences the perception of the town?

To examine these questions, I conducted interviews with six officials who were involved in dealing with the Tair murder and its repercussions at the local and regional levels. This group included three heads of authorities: Sami Bar-Lev, who served as head of the Katsrin Council from 1980 to 2014, including during the time of the murder; Dmitri Apartsev, who succeeded Bar-Lev and remained head of the council at the time of data collection for this study; Eli Malka, who served as head of the Golan regional council from 2001 to 2018. Additionally, I interviewed three other key figures: Vicky Badrian, who served as the speaker of the Katsrin local council from 2011 to 2018 before being succeeded by the Keren Aharon-Bitan, and Dalia Amos, who served as the spokesperson of the Golan Regional Council from 2003 to 2019. The interviews were conducted in 2017–2018 in Katsrin, in the office of the interviewees or in cafes, and lasted between an hour and an hour and a half

The analysis of these interviews revealed three primary findings, consistent with the conclusions drawn from the interviews with the young people.

- The image of the town is perceived as positive: According to the interviewees, Katsrin enjoys a positive image. They emphasized factors such as the establishment of new factories in the industrial zone, visits by national-level decision-makers to the town, the quality of the environment, and the strong sense of community. For instance, Badrian stated, “We are highly regarded… We have a warm and close-knit community. I don’t believe we sense any negativity in our image.”

- The murder did have an impact on the town’s image: When questioned about the lasting effects of the Tair murder on Katsrin’s image a decade after the tragedy, the interviewees acknowledged that it had indeed cast a shadow. However, they noted that over the years, the association between Katsrin and the murder has gradually lessened in people’s minds. Bar-Lev, who was the head of the local council at the time of the murder, commented, “The murder significantly affected Katsrin’s image. When I mention Katsrin in conversation, some people immediately bring up the murder. It’s as if that’s the first thing that comes to their minds.” Malka, who led the Golan Regional Council during the same period, concurred, “I believe it did considerable damage to Katsrin’s image, and to a greater extent than to the Golan as a whole.” Aharon-Bitan also acknowledged the lasting association between the town and Tair’s murder, saying, “I personally feel that, unfortunately, it’s something that remains with us. Katsrin’s name is often closely linked to Tair Rada, just as the school is often recognized as ‘the place where the girl was murdered.’ When I started new positions and people asked me where I was from, mentioning Katsrin would invariably lead to questions about whether I knew Tair Rada.” However, when reflecting on the murder’s significance in terms of the town’s image a decade later, Aharon-Bitan stated, “To say it’s a stain? I’m not sure it’s so much a stain as it is a landmark, unfortunately”.

- The impact of social media activity on the town’s image and how to respond to it: Lastly, the decision-makers were queried about their awareness of the social media activity advocating for justice for Zadorov and their views on how to address it. While they had heard about the activity, they were not well-acquainted with its specifics. In contrast to the perspectives of the young individuals interviewed in the study, the decision-makers believed that the social media activity was minimal and lacked genuine impact. Consequently, they felt that the local authorities should not engage with it.

For instance, Dalia Amos, who served as the spokesperson of the Golan Regional Council during the time of the murder, asserted that social media was a “gray area” where local authorities had limited control over the discourse. She preferred not to participate in these discussions, as her involvement might draw the authority into conversations that could portray it negatively, without providing adequate opportunities for a suitable response. She expressed, “Facebook has evolved into a space for discussions among defense attorneys, categories… the problem is that everything is there—all the materials, facts, rumors, conspiracies… every individual becomes an investigator, an advocate. It has become a sort of courtroom, and therefore, authorities must anticipate how to manage events in a way that leaves less room for discussion.”

Aharon-Bithan, the spokesperson of the local council, also conveyed her belief that responding to social media statements was often unnecessary: “I don’t think it’s necessary to respond, unless it involves defamation that is… psychotic, shattered, and entirely false… I won’t engage in something I wasn’t specifically asked to address because that just fans the flames”.

Apartsev, the head of the Katsrin Council, emphasized the sensational aspects of social media activity: I neither know nor wish to know [this activity]… I don’t involve myself in it, nor do I respond… I primarily view social media as a cesspool and not a reliable source. The reckless way people employ this channel, in an uncontrolled, unethical manner… renders this platform problematic and untrustworthy.

8. Discussion and Conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of image crises in local contexts by demonstrating two key dynamics: first, the long-term reputational impact that a single violent event can have on a small community; and second, the striking discrepancy between how such a crisis is perceived by the general public and how it is dismissed or minimized by local decision-makers.

As social media continues to evolve globally, its influence on organizational and municipal crises has become increasingly significant. This article examines a unique case in which a crisis unfolded on social media yet went unnoticed by decision-makers in Katsrin—a town deeply affected by the murder of Tair Rada and the subsequent wrongful imprisonment of Roman Zadorov. This case is particularly striking due to its prolonged duration, wide-reaching scope, and profound impact on Israel’s digital landscape, fundamentally reshaping public perception of Katsrin in the online sphere.

This research seeks to comprehend the influence of social media activities—particularly the movement advocating for justice for Zadorov—on the image of the location where the crime transpired. Through an exploration of Katsrin’s representation from diverse perspectives, the study elucidates the dynamics involved in image formation on social media and examines its reverberations on local communities.

Employing four complementary research methods, the study delves into different aspects of the crisis. The first method involved a public survey to assess Katsrin’s image; the second was a netnographic study analyzing content on social media, particularly in groups advocating for Zadorov’s justice. The third and fourth methods included interviews with Katsrin’s youth and local decision-makers, respectively. These interviews aimed to understand the crisis’s manifestation on social media and the responses to it. This multi-method approach allowed for a nuanced exploration of the crisis from various perspectives, ensuring a comprehensive understanding of the issue at hand.

This study explored how a reputational crisis may unfold and persist within digital environments—particularly social media—without being formally acknowledged by local authorities. The case of Katsrin, examined through four different research angles, reveals a clear gap between public discourse and institutional perception. While a persistent association between the town and the Tair Rada murder emerged in public and online narratives, decision-makers consistently downplayed its relevance or impact.

A pattern seen across various countries is that remote or previously obscure locales often become infamous after catastrophic events. These “unrecognized crises”—whether due to delayed international attention or underestimation by authorities—leave a permanent stain on the place’s name.

One striking illustration is the Bhopal Gas Tragedy in India (1984), that transformed an otherwise little-known industrial city into a global symbol of corporate negligence (Broughton 2005). The long-term health and environmental consequences were downplayed for years, and only later did the full scale of the disaster enter academic and legal discourse. Similarly, the Fukushima nuclear accident in Japan (2011) revealed how complacency and regulatory blind spots turned a coastal prefecture into a site of global notoriety. Despite prior warnings, the risks were underestimated until it was too late, and Fukushima’s name, much like Bhopal’s, remains permanently tied to technological failure and institutional denial (Shigemura et al. 2014).

Such cases reveal a common pattern: whether rooted in war, political violence, industrial disaster, or natural catastrophe, small or peripheral places can become permanently stigmatized when early warning signs are ignored or minimized. Just as Katsrin’s image in Israel has been shaped by the Rada murder and subsequent online activism, Bhopal and Fukushima exemplify how reputational crises may initially go unrecognized, only to later dominate the identity of a locality. This comparative lens underscores the generalizability of the concept of an “unrecognized crisis” and highlights the importance of proactive monitoring, acknowledgment, and transparent engagement to prevent similar long-term damage in other communities.

This disconnect between public discourse and institutional perception also points to important practical implications for local administrations. If municipal leaders underestimate or dismiss the reputational impact of online narratives, they risk allowing negative associations to persist unaddressed. One way to narrow this gap is by incorporating digital engagement strategies and real-time reputation monitoring into governance practices. Systematic tracking of social media discussions, the use of early-warning tools, and proactive digital communication can help local authorities identify emerging reputational risks at an early stage and respond more effectively. Beyond damage control, such measures may also foster transparency and trust, enabling municipalities to transform online challenges into opportunities for constructive dialogue with their communities.

The findings highlight several key dynamics. First, social media activism—particularly surrounding the Zadorov case—played a significant role in maintaining and amplifying Katsrin’s negative image. Unlike traditional media, which tends to focus briefly on events, online communities sustain attention through prolonged discussions, independent investigations, and user-driven commentary. These activities construct a “parallel narrative” that may hold significant sway over public opinion, even as it remains invisible to or dismissed by institutions.

Second, the study shows a divergence in perception across generations and roles. Young residents of Katsrin, deeply immersed in digital environments, reported feeling that their town is stigmatized and misunderstood. In contrast, local officials expressed confidence in the town’s image, often rejecting the validity or importance of online discourse altogether. This disconnect may indicate generational gaps in media consumption or a reluctance by leadership to engage with unregulated forms of public opinion.

Third, the case sheds light on an underexplored phenomenon: the “unrecognized crisis.” Despite evidence of reputational harm—including in public surveys and youth interviews—authorities declined to frame the situation as a crisis, thereby choosing inaction as a strategy. This aligns with the theoretical concept of “crisis conception” (Turner 1976; Weick 1988), where organizations fail to acknowledge risks that challenge internal narratives or administrative priorities.

This disconnect between the decision-makers’ perception and the actual impact of the crisis on social media calls for further investigation. It raises questions about why such a discrepancy exists: Is it due to the decision-makers’ immersion in town-related work, or other reasons? The phenomenon observed in Katsrin may reflect a broader trend, warranting additional research into similar situations globally, where sustained negative portrayal on social media is recognized by the public but ignored by local authorities.

While this study combines social-media data with survey and interview materials, it is important to note that social-media discourse is not necessarily representative of the wider public. Online discussions often reflect the voices of particularly active or digitally engaged participants, who may differ in demographic characteristics, political views, or intensity of engagement from the general population. Moreover, generational factors are relevant: younger individuals, more immersed in digital platforms, are both more likely to produce social-media content and to perceive its narratives as shaping local image. Older populations, who rely more heavily on traditional media or interpersonal communication, may experience the reputational dynamics of Katsrin differently. These considerations highlight the value of triangulating social-media analysis with survey and interview data, as done here, but also underscore the need for caution in generalizing online discourse to society at large.

This study not only documents a unique case of a crisis/non-crisis situation but also sets the stage for theoretical expansion in understanding and conceptualizing such phenomena. It underscores the need for a deeper academic exploration of crises in the context of social media and general crisis management. This Katsrin case study serves as a foundational piece for future empirical and theoretical work, aiming to deepen our comprehension of crisis recognition and management in the increasingly digitalized world of today.

The study contributes to scholarship on crisis perception, local governance, and the role of digital platforms in shaping collective memory. It suggests that in the age of social media, reputational crises can develop and persist without clear triggering events, formal recognition, or institutional response.

Like any qualitative and mixed-method study, this research has limitations. While the online data was collected from large, public Facebook groups, the discourse analyzed may reflect the views of more vocal or engaged users, rather than a representative cross-section of the broader public.

Future studies could expand the scope to include other towns in Israel or globally that experienced similar long-term reputational crises following violent or traumatic events. Comparative research could also shed light on factors that affect whether a crisis is publicly acknowledged or institutionally ignored.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ariel University’s ethics committee (protocol code AU-COM-ALO-20230829 and date of approval 29 August 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Recorded consent was used because many interviews were conducted by phone and for purposes of standardization. The wording was: “This questionnaire is part of an academic study and is conducted anonymously. We would be grateful for your participation. If you prefer that part or all of your interview not be included in the study, please let us know. We will send you the interview transcript if you wish”. In addition, the use of identifiable personal information from social media was done with the individuals’ written consent.

Data Availability Statement

Data is available from the author upon request.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Inbal Laks-Freund, Bar Hofshi and Zohar Edri for their assistance in preparing this manuscript for publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Allen, Katrina M. 2006. Community-Based Disaster Preparedness and Climate Adaptation: Local Capacity-Building in the Philippines. Disasters 30: 81–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Avraham, Eli. 2003. Promotion and Marketing of Cities in Israel: Strategies and Advertising Campaigns to Attract Tourists, Investors, Entrepreneurs and Residents. Jerusalem: Florsheimer Institute for Policy Studies. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, Eli, and Eran Ketter. 2012. Media Strategies for Marketing Places in Crisis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Avraham, Eli, and Eran Ketter. 2016. Tourism marketing for destinations with negative images. In Tourism marketing for developing countries: Battling Stereotypes and Crises in Asia, Africa and the Middle East. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 67–82. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Israel, Dori. 2016. “The Tube” Celebrates 900K and Ynet Is in a Hysterical Pressure: Ranking of Facebook Pages for January 2016. Tel Aviv: Mizbala. Available online: http://mizbala.com/digital/social-media/109150 (accessed on 20 September 2025).

- Boin, Arjen, Magnus Ekengren, and Mark Rhinard. 2020. Hiding in plain sight: Conceptualizing the creeping crisis. Risk, Hazards & Crisis in Public Policy 11: 116–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Broughton, Edward. 2005. The Bhopal disaster and its aftermath: A review. Environmental Health 4: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coombs, W. Timothy, and J. Sherry Holladay. 2012. The paracrisis: The challenges created by publicly managing crisis prevention. Public Relations Review 38: 408–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heitner, U. 2019. Katsrin, the capital of the Golan. Horizons in Geography 95: 45–59. (In Hebrew). [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Yan, Brooke Fisher Liu, and Lucinda L. Austin. 2014. Examining the Role of Social Media in Effective Crisis Management: The Effects of Crisis Origin, Information Form, and Source on Publics’ Crisis Responses. Communication Research 41: 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Shannon, and Krzysztof Kubacki. 2014. Branding places with social problems: A systematic review (2000–2013). Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 10: 218–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, Naim. 2008. Collaborative emergency management: Better community organizing, better public preparedness, and response. Disasters 32: 239–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kotler, Philip, Donald H. Haider, and Irving J. Rein. 1993. Marketing Places: Attracting Investment, Industry, and Tourism to Cities, States, and Nations. New York: The Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lev-On, A. 2023a. Democratizing the discourse on criminal justice in social media: The activity for justice for Roman Zadorov as a case study. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10: 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-On, A. 2023b. The Murder of Tair Rada and the Roman Zadorov Affair: Establishment, Justice, Citizens and Social Media. Rishon Lezion: Yedioth Books. (In Hebrew) [Google Scholar]

- Lev-On, A. 2024. Mediatization and justice: How public participation influences legal processes through online discovery. Mediatization Studies 8: 47–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev-On, A., and N. Steinfeld. 2020. “Objection, your honor”: Use of social media by civilians to challenge the criminal justice system. Social Science Computer Review 38: 315–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauchant, Thierry C., and Ian I. Mitroff. 1992. Transforming the Crisis-Prone Organization: Preventing Individual, Organizational, and Environmental Tragedies. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Saroj, Anita, and Sukomal Pal. 2020. Use of social media in crisis management: A survey. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 48: 101584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigemura, Jun, Takeshi Tanigawa, Daisuke Nishi, Yutaka Matsuoka, Soichiro Nomura, and Aihide Yoshino. 2014. Associations between disaster exposures, peritraumatic distress, and posttraumatic stress responses in Fukushima workers following the 2011 nuclear accident. PLoS ONE 9: e87516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Turner, Barry A. 1976. The organizational and interorganizational development of disasters. Administrative Science Quarterly 21: 378–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tutia, Aviv. 2016. I Want to Take You to the Day I Lost Tair Radha. Rishon LeZion: ynet. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, Karl E. 1988. Enacted sensemaking in crisis situations. Journal of Management Studies 25: 305–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).