1. Introduction

This study, undertaken in the Australian Higher Education sector, produced a blueprint for the co-design of research by non-Indigenous researchers with Indigenous people living with disability. It evolved out of the organic leadership of Indigenous supervision in this research and the desire of the lead researcher (i.e., the PhD candidate—herein referred to as the researcher) to acknowledge the authority of Indigenous advisors living with disability. A conceptual framework was developed and applied throughout this research. This conceptual framework reallocated power in the research relationship away from the PhD researcher to the owners of the knowledge being researched. As such, this provides a way in for non-Indigenous researchers to contribute to the research goals of Indigenous populations who live with disability.

Alvesson and Sandberg (

2013) prescribed innovative and imaginative research methods and introduced the path-up scholarship methodology. Path-up scholarship proposes challenging existing frameworks and the use of alternative methodologies. It refers to a process of immersion for the researcher, who questions themselves, their values, their biases, and the applicability of standard research methods, rather than following research conventions to secure acceptance. They state that as researchers, we should be: Committed to … ideas we care about rather than focusing on what our publications will do for our image, our compensation, or our careers. That is, we need less instrumental gap-spotting and publication-prioritising sub-specialists working for a long time only within one area, and more researchers with a broader outlook, curious, reflective, willing and able to question their own frameworks and consider alternative positions, and eager to produce new insights at the risk of some short-term instrumental sacrifices, that is, a more critical and path-(up)setting scholarship mode (p. 143).

Similar to decolonisation methodologies, including universal design of learning, cultural safety, person-centredness, and social inclusion, the research focus of path-up scholarship is on those whom it serves rather than the system.

Charbonneau-Dahlen (

2020), an Indigenous American researcher, developed Symbiotic Allegory as an Innovative Indigenous Research Methodology that combines traditional Indigenous storytelling with Western research methods.

Charbonneau-Dahlen (

2020, p. 35) affirmed the ‘importance of creating methodologies that incorporate the ways of knowing of the group being studied’, facilitated by ‘a member of the group being studied who is able to collect data in a respectful and culturally harmonious way for the purpose of disseminating the research’. Careful, supportive, creative, purposeful, and responsive are descriptors for these methods of innovative research. It is with this approach that

Kerr (

2021) embarked upon her PhD research, White Questions, Black Answers, as a non-Aboriginal woman, from which this paper is drawn. The research did not commence with an established methodology to guide research activities; instead, it responded iteratively with methods compatible with the conceptual framework (

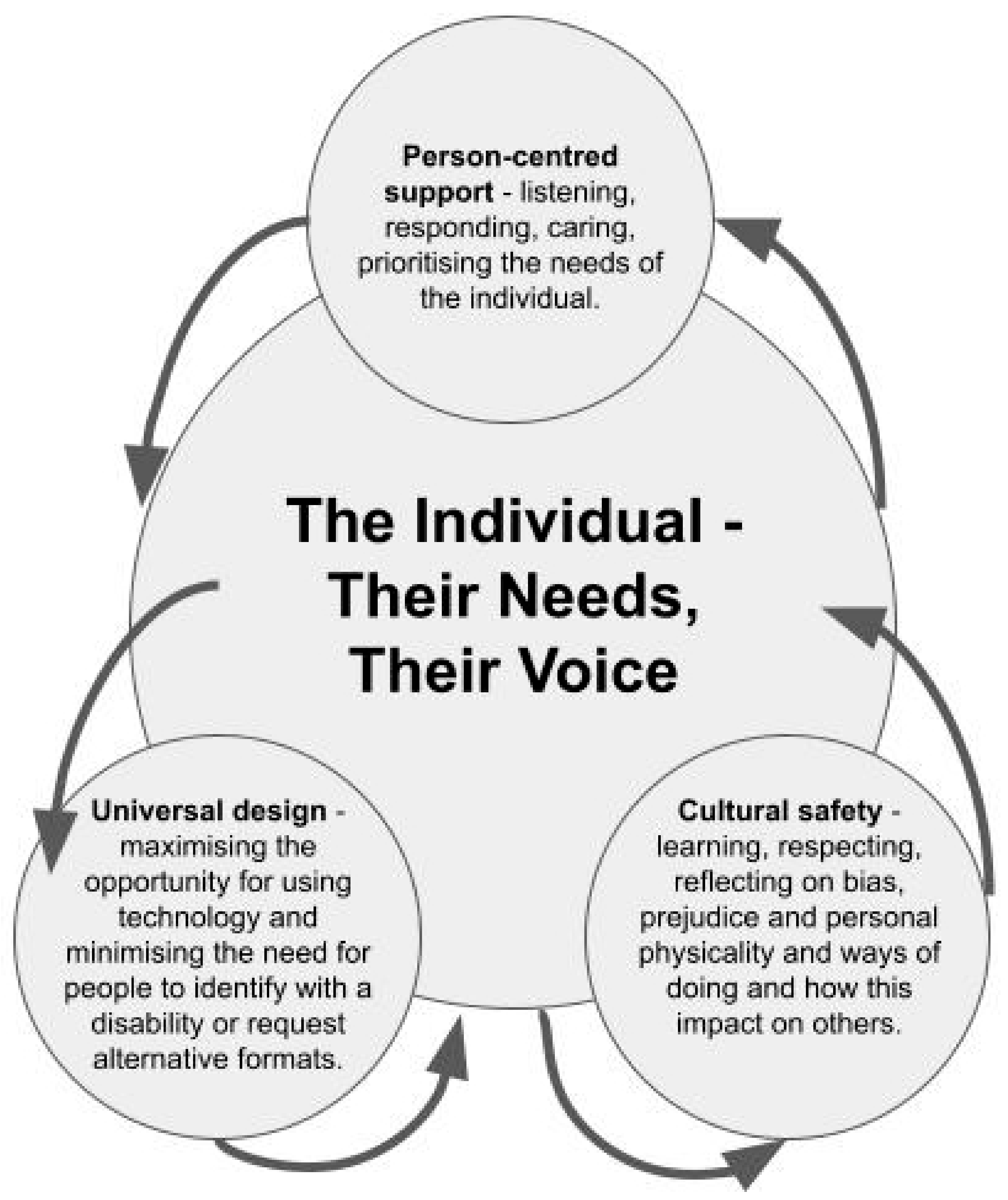

Figure 1), which evolved in partnership with the Indigenous leadership of those with an Indigenous standpoint on disability: John Gilroy, Roslyn Sackley, Maria Robinson, and Naomi Carolin.

Involvement of those with lived experience of being an Indigenous Australian living with a disability in this research through supervision, advice, or participation constituted the beating heart of the research and drove its purpose, lens, and activities. It was through deep mutual respect that the non-Indigenous researcher was entrusted to undertake the research and supported through the five-year duration of the research journey. Those with lived experience were not chosen by the researcher as contributors to support her research intentions; rather, the researcher was chosen by those with lived experience to serve and undertake research that they deemed necessary and valuable. This resulted in a collaborative research relationship with leadership by those with an Indigenous standpoint on disability. The research questions that they wanted answered were:

What are universities doing concerning supporting Indigenous students with disability?

What lessons can be learned from listening to the stories of Indigenous people with disability who have lived experience navigating the Australian Higher Education Sector?

The researcher was known to those with an Indigenous Standpoint through previous collaborations regarding the support of Indigenous students with disability. They had been colleagues while working with Macquarie University Accessibility Services, a national service that provided accessible learning materials for the Australian Higher Education Sector between 2004 and 2014. Relationships and trust were further enhanced through open and frequent communication between the researcher and the team throughout the entirety of the project. Their counsel was sought with regard to the Indigenous perspective of disability and gender-specific ways of doing and knowing. As women with leadership roles in their communities, they each contributed wisdom and insight that would not have been possible without their central role in the project encompassing the ongoing development of mutual trust between the Indigenous Advisory Group and the researcher.

2. Method

Founded on Indigenous Standpoint Theory, as presented by

Gilroy (

2009a), the methodology of this research foregrounds the central role of Indigenous people with lived experience of disability—in the study design, its implementation, and in the validation of the results. This research applied a mixed methods convergent parallel design. As described by

Creswell and Plano Clark (

2011), the study involved collecting and analysing two distinct datasets and provided a solid methodology for validation of the quantitative and qualitative data collected in this study. The Quantitative Track comprised an audit of Australian university websites and a review of Disability Action Plans to ascertain the nature of service delivery. The Qualitative Track comprised listening to the stories and truth-telling of five Indigenous people with disability who had undertaken higher education in Australia. Truth-telling in the context of this research involved sessions going on for as long as participants needed and being conducted in the manner they requested. Following the collection and analysis of the unique datasets, a process of comparison and identifying relationships between the two Tracks was undertaken.

This research was:

Supervised and led by an Australian Indigenous scholar who is recognised nationally for his work in Indigenous health and disability, thereby ensuring that research activities undertaken have been mindful of and informed by someone with an Indigenous standpoint.

Informed, guided, and validated by an Indigenous Advisory Group, and

Supported by an Indigenous cultural broker, who attended all interviews.

The Advisory Group comprised three Aboriginal people with lived experience of disability. Their role in this research was as supportive peers guiding the embedding of Indigenous standpoint throughout this research. The Advisory Group’s involvement was crucial in securing the participation of Indigenous people with disability who had undertaken higher education and in laying the foundation for trust and open, honest communications. The Advisory Group also played a crucial role in validating the research findings.

Roslyn Sackley was employed in the role of cultural broker and was present for all interviews. Roslyn is a Nyiampaa and Wiradjuri woman with total vision loss due to meningitis as an infant. Roslyn has taught in the Australian Capital Territory and New South Wales primary, senior secondary, TAFE, and university sectors. As a cultural broker, she did not ask any research questions, comment on responses, or participate in data collation or analysis. The purpose of her role was to:

Ensure the embedding of cultural safety into the data collection process.

Improve the power balance in the interview process in favour of the interviewee.

Provide: (i) empathy and cultural support to the interviewee, (ii) feedback for better ways of conducting the research to the researcher, and (iii) reassurance of the efficacy and purpose of the research for the participants.

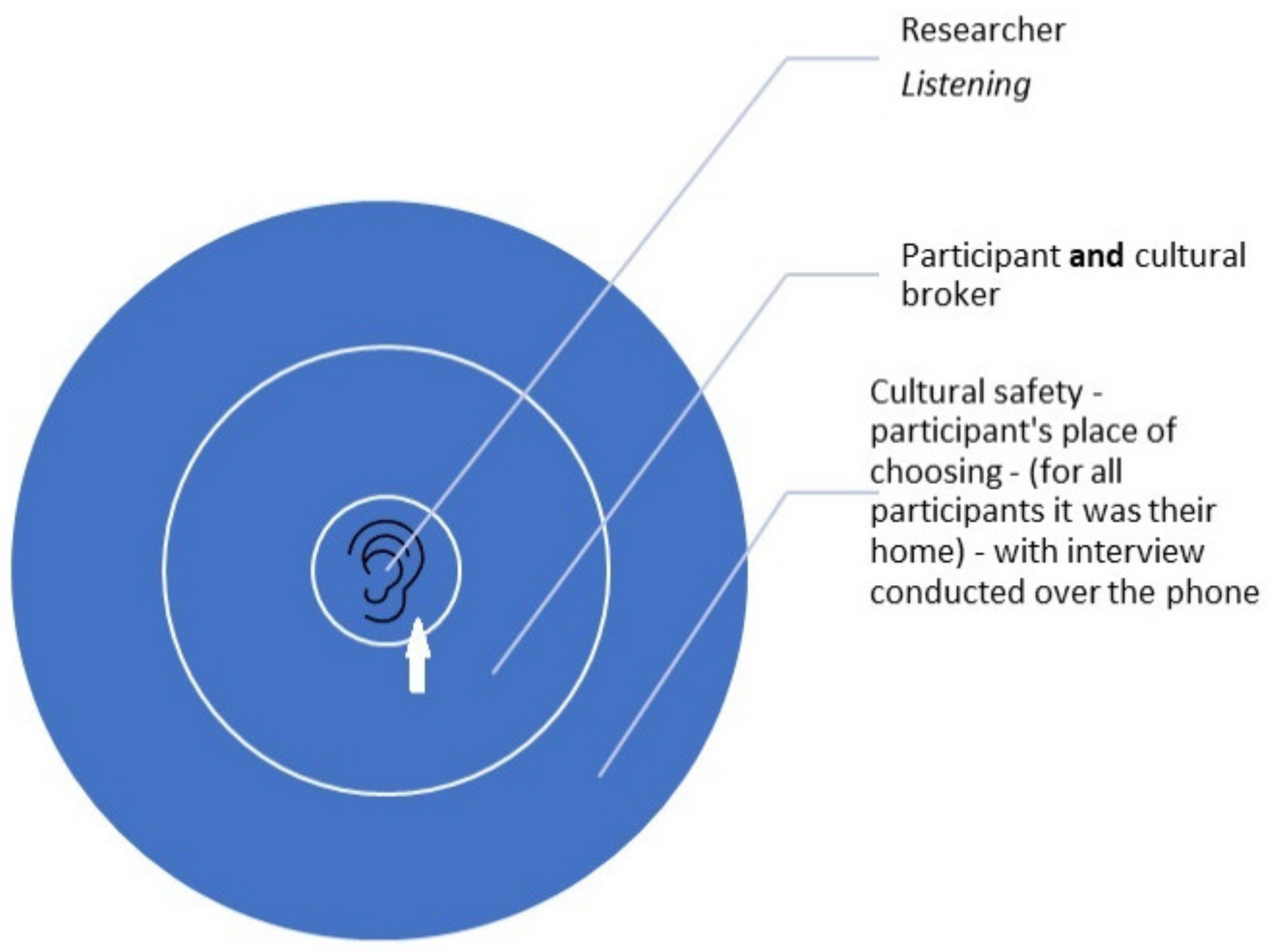

Figure 2 represents how the conceptual framework was applied to the interviews and illustrates the power relationship between the researcher, a non-Indigenous woman without disability, and the Indigenous Australian participants living with disability. The image shows three concentric circles—the researcher is represented as the smallest inner circle. The next circle represents the participant and the cultural broker together (i.e., the cultural broker is there to support the participant, not the researcher), with a two-way line leading to the researcher representing sharing. The outer circle represents cultural safety. Participants were given the option of where and how they wanted to participate in the study. Participants lived in various states and territories while undertaking their studies; however, at the time of participation, they were residing in Sydney (one female), North Coast New South Wales (one male), South Coast New South Wales (one male), Canberra (one female), and Adelaide (previously Darwin; one female). Due to the commitment made to the participants to preserve anonymity and avoid plausible or accidental disclosure, we are not in the position to provide further demographic data, other than to say that they were between the ages of 26 and 70, all were Indigenous, and all had disabilities, which included sight impairment, deafness, intellectual, psychosocial, and physical disabilities.

A time limit was not set for the interviews—each participant set the duration and content of their session. Each session was also attended by the cultural broker, who helped participants feel relaxed and empowered during the research process. The cultural broker would introduce themselves and the researcher, talk about their family, and reflect back comments when participants mentioned their own families and communities. To avoid rushing participants, interviews commenced when the cultural broker indicated that it was the right time to proceed. The entire focus of this methodology was to empower the participants and help them both relax and gain an understanding of the respect that the researcher had for them and their knowledge. Five participants were invited to tell their personal stories of engagement with higher education, and the researcher listened. Sessions were recorded and interviews were transcribed and analysed. However, during the interviews, no notes were taken; instead, the researcher and the cultural broker listened and engaged with what was being said by the participant, considering the impact of their experiences on their lives.

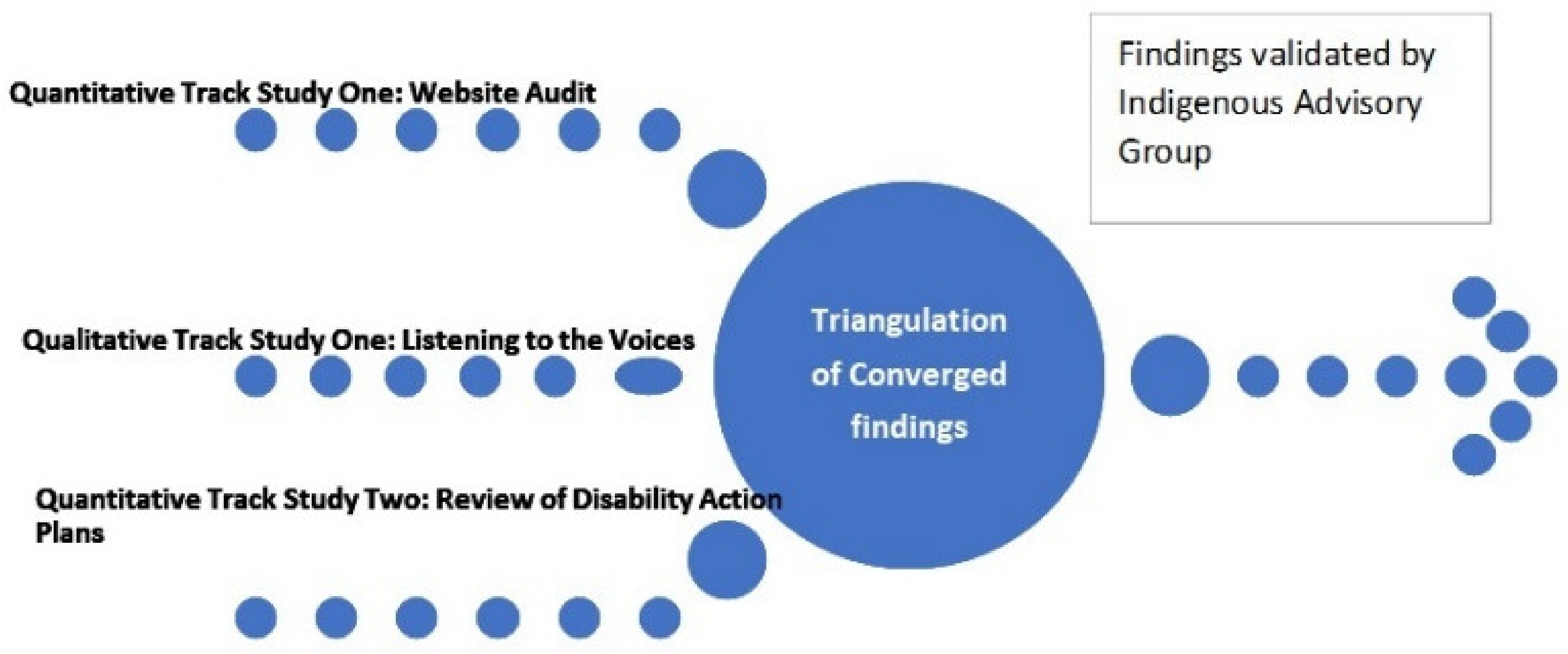

Three studies, consisting of two quantitative and one qualitative study and a final validation meeting with the Indigenous Advisory Group, provided insights into the experience of Indigenous students with disability engaging with the Australian Higher Education Sector. The first study that was undertaken in 2016 involved 40 Australian universities, identifying what services and supports they were providing to students with disability, Indigenous students, and Indigenous students with disability. The second quantitative study that was undertaken in 2020 examined the disability action plans of the same 40 Australian universities to capture strategic planning with regard to supporting the same student cohorts. The qualitative study focused on capturing the lived experience of Indigenous people with disability undertaking higher education. These insights were validated at the conclusion of the research through a triangulation process of all collected data.

The triangulation method adopted was drawn from

López López (

2015) as a method to verify and facilitate:

the comparison of information obtained from the application of different techniques … and triangulation of information sources, whose value consists of verifying the inferences extracted from an information source by means of another information source.

(p. 180)

The data and findings from the final verification meeting with the Indigenous Advisory Group also contributed to the verification of the findings. This provided the researcher with greater confidence in the findings, as

Oleinik (

2017) stated:

triangulation in content analysis increases the validity and reliability of the outcomes.

(p. 176)

This process is illustrated in

Figure 3 (

Kerr 2021).

The approach taken as a non-Indigenous researcher was designed to ensure cultural safety and empowerment for all participants who contributed their Indigenous standpoint to the research. This approach is in line with what

Daniels-Mayes (

2023) calls BlakAbility, where research addressing the intersectionality of Aboriginality and disability is led by those with lived experience and an Indigenous standpoint on disability. She states:

Indigenous people living with disability battle with issues related to racism, ableism and colonisation, impacting well-being and life outcomes throughout the life course. Yet, the intersection of Aboriginality and disability remains vastly under-researched. Research using intersectionality embedded with decolonising knowledges and practices and Indigenous standpoints on disability, which is informed and led by those with lived experience (BlakAbility), is urgently needed. Failing to do so serves only to perpetuate inequity and oppression borne out of two centuries of colonisation and will allow disability researchers to continue theorising about Indigenous people without recognising and embedding their understandings and lived experiences that are shaped by their personal, cultural and historical contexts.

(p. 4)

Key to this methodology was the desire to ensure that participants did not feel coerced into sharing their stories, knowledge, and wisdom and, at all times, felt respected, listened to, and revered as lived experience specialists. The goal was to increase each study’s rigour and ensure the data’s validity, resulting in the production of outputs that have utility throughout the higher education sector for the benefit of Indigenous students with disability. Following the completion of data collection and analysis of findings from both Tracks, in line with the mixed methods convergent parallel design methodology, the studies’ findings were brought together, as described by

Creswell and Plano Clark (

2011):

the researcher collects and analyses both quantitative and qualitative data during the same phase of the research process and then merges the two sets of results into an overall interpretation.

(p. 77)

After aligning the validated findings and analysing the answers to the research questions, the Framework for All was developed, as seen in

Figure 1.

4. Discussion

Indigenous Standpoint Theory (IST) and decolonisation formed the foundational layer for the theoretical context. As a non-Aboriginal researcher undertaking this PhD research, the first question that needed to be answered was whether or not it should be undertaken at all. Should research such as this, which affects Indigenous people’s lives, only be conducted by Indigenous researchers? In addressing this question,

Dew et al. (

2019) used the insider/outsider approach, whereby non-Indigenous researchers (the outsiders) walk side-by-side with Indigenous researchers (the insiders) towards a shared goal of improving the lives of the Indigenous people and their communities being researched.

Foley (

2003) raised the subject of Indigenous Epistemology and IST in the context of wanting to provide an alternative research methodology and framework for Indigenous researchers. In undertaking his PhD, his concern was Indigenous researchers whose research activities were being frustrated and thwarted by being forced to accept Western, ethnocentric research methodology. He wanted to provide a meaningful alternative that would both scaffold and enable Indigenous scholars’ research activities. IST was intended to be an Indigenous framework designed by an Indigenous scholar for Indigenous scholars.

Foley (

2003) provided four criteria for practitioners to form the discussion basis for determining Indigenous standpoint. He stated that the practitioner must:

Be Indigenous, well versed in social theory, critical sociology, post structuralism and post modernism … Indigenous research must be for the benefit of the researchers community or wider Indigenous community and/or Indigenous research community … wherever possible the traditional language should be the first form of recording.

(p. 50)

The work of

Smith (

2012) concurs with

Foley (

2003)’s assertion that Indigenous research should only be conducted by Indigenous researchers. Historically, those termed ‘white settler researchers’ by Smith have approached research with Indigenous communities from a deficit perspective, misrepresenting findings, and using them to reinforce colonising agendas.

Smith (

2012) stated that:

From an indigenous perspective Western research is more than just research that is located in a positivist tradition. It is research which brings to bear, on any study of indigenous peoples, a cultural orientation, a set of values, a different conceptualisation of such things as time, space and subjectivity, different and competing theories of knowledge, highly specialised forms of language, and structures of power.

(p. 92)

Understandably, many Indigenous communities and Indigenous academics see no place for the white researcher in this space. However, this stance does not consider the impact already made by Indigenous researchers on decolonising academic perspectives. Due to the decolonising actions and research conducted by Indigenous scholars using Indigenous methodologies, white researchers are coming into this research field with the desire to contribute to the decolonising agenda rather than reinforce colonising norms. If, as stated by

Foley (

2003) and

Smith et al. (

2019), Indigenous research is to be considered research conducted by Indigenous people, about Indigenous people, and for the benefit of Indigenous people, then it could be concluded that the research that has been shared in this article is not Indigenous research. It is agreed that no amount of reading or empathetic listening could provide the appropriate foundation for assuming that the researcher is accurately applying the lens of Indigenous experience to claim an Indigenous standpoint on their own merit. However, this PhD study focused on the interface of the higher education system with Indigenous students with disability and was conducted by a non-Aboriginal Australian with experience in the higher education sector. It sought to learn what the system could do to better support Indigenous students with disability—it was not seeking change or action from the students. Thus, the title: White Questions—Black Answers.

In his PhD thesis,

Gilroy (

2009a), also an Indigenous scholar, developed a conceptual framework for research and policy development regarding Aboriginal people with disability; in doing so, he merged IST with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (

World Health Organization 2001). In presenting his framework,

Gilroy (

2009a) attempted to provide a way for non-Indigenous scholars to adopt IST with the involvement and leadership of Indigenous people in the research process. He stated that ‘non-Aboriginal researchers can adopt IST in their research regarding Aboriginal people only if Indigenous people were involved in the research process’ (p. 129).

In developing his framework,

Gilroy (

2009b) embedded six criteria in the IST component, which speak directly to the non-Indigenous researcher. They are the need for Aboriginal Community inclusion in the research; for researchers to be well-versed in the influence and impact of European colonisation and dispossession of Aboriginal communities’ traditional lands and cultures; for researchers to be part of the struggle for Aboriginal communities to be self-determining; to acknowledge the cultural interface that they bring to the research; the similarities and differences between communities; and to use, wherever possible, local Indigenous languages (

Gilroy 2009b, p. 132).

Gilroy’s (

2009a) framework provides a way for non-Indigenous researchers to examine systems and make them more responsive and effective for Indigenous students, clients, and patients. Global research on education and government systems is increasingly being undertaken by private consultancy firms (

Gunter et al. 2014;

KPMG 2020). Without a framework that can be readily adopted, Indigenous standpoint risks being excluded from the process, in which case the colonisation agenda will prevail. Therefore, a framework within which white researchers can operate is crucial so that the research they conduct is culturally safe and overseen by Indigenous stakeholders. Safeguards must be in place to ensure that power remains with Indigenous stakeholders. If Indigenous stakeholders oversee interpretations and outputs, the research remains set to benefit Indigenous individuals, families, and communities.

Therefore, this study used

Gilroy’s (

2009a) IST, embracing the leadership and guidance of those with an Indigenous standpoint. This research was initiated after a request made to the researcher from two Indigenous people with disability who subsequently joined the Indigenous Advisory Group for this study’s duration. Activities were conducted under the guidance of an Indigenous scholar (nominated by one of the people who requested the research) and the Indigenous Advisory Group. The researcher did not assume the mantle of having an Indigenous standpoint; however, as a non-Aboriginal researcher, respectfully embraced oversight and guidance from those with an Indigenous standpoint, thus securing the benefit of the Indigenous standpoint for the research, its execution, analysis, findings, and recommendations.

Key to the methods developed and adopted for this research was empowering those with lived experience of the subject matter being researched. In essence, the research model had built-in checks to ensure that the researcher was not unwittingly reinforcing colonising norms. The relationship between the researcher, the Indigenous Advisory Group, and the cultural broker was and continues to be one of respect and walking together towards a common goal. It was not one of hierarchy fueled by the researcher’s personal goals and ambitions, but one where the Indigenous Advisory Group entrusted the researcher with the responsibility of discovery and dissemination of the findings from the research. For five years, the group worked with the researcher, and at its conclusion, bore witness to the final viva voce examination of the thesis.

The methodology used within the thesis bears relevance to the paradigm of inclusive research (

O’Brien 2023), where ownership over the research process is in the hands of researchers with lived experience of intellectual disability.

Grace et al. (

2022) have referred to the process, not unlike that of indigenous methodology, as one of decolonising the way research has been done in the past to people with profound intellectual disabilities and demanding respect for wider ways of knowing, doing research, and being human. The learnings from this study for inclusive research also lie in the relevance of the Framework for All (see

Figure 1). Much of the reporting of inclusive research focuses on how people with intellectual impairments are involved as co-researchers and the accessible methods used to collect and analyse data (

O’Brien 2023), whereas the Framework for All holds a message for all co-researchers both with and without disability on how to interact beyond considerations of accessibility with participants who live with disability. It reminds those involved in inclusive research that a core aspect of their role is to be person-centred, listening deeply to those they interview/observe; using technology/multimedia to involve participants previously overlooked due to communication issues; as well as giving due consideration to cultural safety to circumvent prior cultural bias and prejudice. It challenges the traditional power balance of the research relationship and transforms the research beyond participatory to emancipatory.

Stone and Priestley (

1996), when addressing the related question of who should undertake disability research, identified that:

the emancipatory model requires … full ownership of the means of research production—ownership by the research participants not the researcher.

(p. 702)

Kerr (

2021), focused on ensuring the empowerment of participants during the interview process, with a cultural broker present during each interview (see

Figure 2). This approach is worthy of further discussion and research to explore its application to inclusive research involving participants with different disabilities. For example, when undertaking research with participants living with intellectual impairments, would the individual participants benefit from having another person in the interview who also lived with an intellectual impairment?