Problematizing Child Maltreatment: Learning from New Zealand’s Policies

Abstract

1. Introduction

- How is child maltreatment constructed in the child protection policies?

- What assumptions underlie the construction of child maltreatment?

- What is omitted from the construction of this problem?

2. Method and Materials

2.1. Qualitative Content Analysis

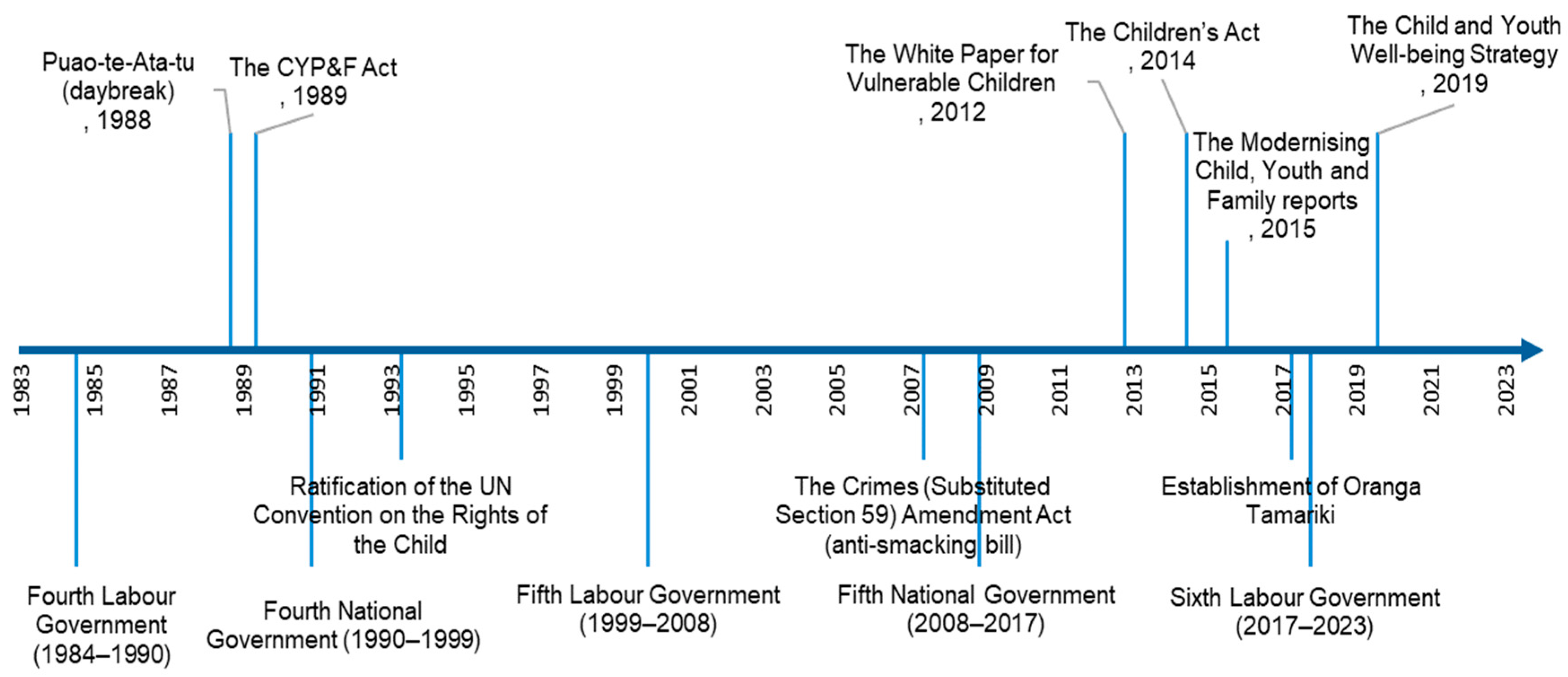

2.2. Data Collection

- Puao-te-Ata-tu (daybreak), 1988 (Māori Perspective Advisory Committee 1988).

- The 1989 Children, Young Persons and their Families Act, amended in 2017 as the Oranga Tamariki Act (Oranga Tamariki Act 2017).

- The 2012 White Paper for Vulnerable Children (Volumes I and II) (Ministry of Social Development 2012a, 2012b).

- The 2014 Children’s Act (Children’s Act 2014).

- The 2015 Modernising Child, Youth and Family report, 2015 (Interim and Final reports) (Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family 2015a, 2015b).

- The 2019 Child and Youth Well-being Strategy (DPMC 2019).

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Individualization of Child Maltreatment in the Child Protection Policy

the Government will focus on vulnerable children in a way that has never been done before. The White Paper for Vulnerable Children sets out a programme of change that will shine a light on abuse, neglect, and harm by identifying our most vulnerable children and targeting services to them ….

vulnerable children are children who are at significant risk of harm to their well-being now and into the future as a consequence of the environment in which they are being raised and, in some cases, due to their own complex needs. Environmental factors that influence child vulnerability include not having their basic emotional, physical, social, developmental and/or cultural needs met at home or in their wider community.(Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 6; italics added)

vulnerable children are those who are at significant risk of harm now and in the future as a consequence of their family environment and/or their complex needs, as well as those who have offended or may offend in the future.(Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family 2015b, p. 41; italics added)

the White Paper outlines a set of reforms that help to ensure that parents, caregivers, family, whānau and communities understand and fulfil their responsibilities towards children, as the single most critical factor in the care and protection of vulnerable children.(Ministry of Social Development 2012a, p. 2; italics added)

a working breadwinner is the best form of security a family can get … Jobs bring financial and social rewards, building family strength and pride … Recent welfare reforms which focus on helping more people back to work, with the financial and social benefits that brings, will play a big part in preventing vulnerability … Programmes that support children to achieve in education, such as those delivered through the Youth Guarantee, the new Youth Service, and enhanced education and training opportunities, combine to get young people ready for work and help grow our economy … Though income poverty alone does not cause or excuse child abuse, we know that struggling to make ends meet places extra stress on families … We also know that it is what parents do that matters most.(Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 26, italics added)

amending the Crimes Act in 2011 to: … broaden the scope of the duties of parents and those with actual responsibility for children. These people will be held liable if they fail to take reasonable steps to protect a child from injury. Thoughtlessness or ignorance is no longer a defence, and penalties for ill-treatment or neglect of a child have been doubled to a maximum of 10 years’ imprisonment.

the Government will extend and systematise existing arrangements for monitoring high-risk adults to include those subject to the proposed Child Abuse Prevention Order and other groups of high-risk adults, and to ensure that relevant information remains accessible over time.

the best place for a child is in the safe, loving and stable care of their families, whānau, hapū, iwi or other family group. A stable and quality home environment with love and trust influences a child and young person’s wellbeing every day, and their ability to form attachments to others.(DPMC 2019, p. 35; italics added)

3.2. Understanding Child Protection Policy in the Context of the Social Investment Approach

the children of today are also the parents, workers and business and community leaders of tomorrow. To ensure future economic and social success, it is important that children are healthy, well nurtured and well educated so they are well equipped to assume these future roles. Investment in children can reduce the emergence of problems that have high social and fiscal costs.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

4.1. Discussion

4.2. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adamson, Peter. 2007. Child Poverty in Perspective: An Overview of Child Well-Being in Rich Countries. Innocenti Report Card 7. UNICEF. Available online: https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/73187/1/Document.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Adler, Nancy. E., Elissa S. Epel, Grace Castellazzo, and Jeannette R. Ickovics. 2000. Relationship of subjective and objective social status with psychological and physiological functioning: Preliminary data in healthy, White women. Health Psychology 19: 586–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afifi, Tracie. O., Tamara Taillieu, Mark A. Zamorski, Sarah Turner, Kristene Cheung, and Jitender Sareen. 2016. Association of Child Abuse Exposure With Suicidal Ideation, Suicide Plans, and Suicide Attempts in Military Personnel and the General Population in Canada. JAMA Psychiatry 73: 229–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreassen, Cecilie S., Joël Billieux, Mark D. Griffiths, Daria J. Kuss, Zsolt Demetrovics, Elvis Mazzoni, and Stale Pallesen. 2016. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 30: 252–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babiak, Paul, and Robert D. Hare. 2009. Snakes in Suits: When Psychopaths Go to Work. New York: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

- Bacchi, Carol Lee. 2009. Analysing Policy: What’s the Problem Represented to Be? Victoria: Pearson Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, Joel. 2003. The Corporation [Film]. Big Picture Media Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, Joel. 2005. The Corporation: The Pathological Pursuit of Profit and Power. ([Rev. and exp. ed.]. ed.). New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bakan, Joel. 2011. Childhood under Siege: How Big Business Targets Children. (1st Free Press hardcover ed. ed.). New York: Free Press. [Google Scholar]

- Becroft, Andrew. 2017. Family Group Conferences: Still New Zealand’s Gift to the World. Wellington: Office of the Children’s Commissioner. [Google Scholar]

- Boden, Joseph M., David M. Fergusson, and John Horwood. 2009. Experience of sexual abuse in childhood and abortion in adolescence and early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect 33: 870–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boden, Joseph M., John Horwood, and David M. Fergusson. 2007. Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and subsequent educational achievement outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect 31: 1101–14. [Google Scholar]

- Boston, Jonathan, and Derek Gill. 2017. Social Investment: A New Zealand Policy Experiment. New York: Bridget Williams Books. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, Brian. 2014. Positionality: Reflecting on the Research Process. The Qualitative Report 19: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breslau, Naomi, Karestan C. Koenen, Zhehui Luo, Jessica Agnew-Blais, Sonja Swanson, Renate M. Houts, Richie Poulton, and Terrie E. Moffitt. 2014. Childhood maltreatment, juvenile disorders and adult post-traumatic stress disorder: A prospective investigation. Psychological Medicine 44: 1937–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, Paul. 2013. Inequalities in Child Welfare: Towards a New Policy, Research and Action Agenda. The British Journal of Social Work 45: 6–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bywaters, Paul, Geraldine Brady, Tim Sparks, Elizabeth Bos, Lisa Bunting, Brigid Daniel, Brid Featherstone, Kate Morris, and Jonathan Scourfield. 2015. Exploring inequities in child welfare and child protection services: Explaining the ‘inverse intervention law’. Children and Youth Services Review 57: 98–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpenter, David O., and Rick Nevin. 2010. Environmental causes of violence. Physiology & Behavior 99: 260–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, Jenny, Mark Selden, and Ngai Pun. 2020. Dying for an iPhone: Apple, Foxconn, and the Lives of China’s Workers. Chicago: Haymarket Books. [Google Scholar]

- Children’s Act, NZ. 2014. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2014/0040/latest/whole.html?search=ts_act%40bill%40regulation%40deemedreg_children%27s+act_resel_25_a&p=1#DLM5501618 (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Clapton, Gary. 2022. Beyond Intention. The Draft National Guidance for Child Protection in Scotland (2020): A Case Study of a Scottish Policy Document. Scottish Affairs 31: 41–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Bruce M. 2016. Psychiatric Hegemony: A Marxist Theory of Mental Illness. London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Cullen, Francis T., Gray Cavender, William J. Maakestad, and Michael L. Benso. 2006. Corporate Crime under Attack: The Fight to Criminalize Business Violence, 2nd ed. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, Gavin, Ciaran Shannon, Ciaran Mulholland, and Jim Campbell. 2009. A Longitudinal Study of the Effects of Childhood Trauma on Symptoms and Functioning of People with Severe Mental Health Problems. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation 10: 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, John, David Wann, and Thomas H. Naylor. 2014. Affluenza: How Overconsumption Is Killing Us—And How to Fight Back. San Francisco: Berrett-Koehler Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- DPMC. 2019. Child and Youth Wellbeing Strategy; Wellington: Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. Available online: https://www.childyouthwellbeing.govt.nz/sites/default/files/2019-08/child-youth-wellbeing-strategy-2019.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family. 2015a. Final Report: Investing in New Zealand’s Children and Their Families; Wellington: Ministry of Social Development. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/corporate/expert-panel-cyf/investing-in-children-report.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family. 2015b. Interim Report; Wellington: Ministry of Social Development. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/evaluation/modernising-cyf/interim-report-expert-panel.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Featherstone, Brid, Kate Morris, Brigid Daniel, Paul Bywaters, Geraldine Brady, Lisa Bunting, Will Mason, and Nughmana Mirza. 2019. Poverty, inequality, child abuse and neglect: Changing the conversation across the UK in child protection? Children and Youth Services Review 97: 127–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, Harry. 2004. Protecting Children in Time: Child Abuse, Child Protection and the Consequences of Modernity. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez, Elizabeth, and Nicola Atwool. 2013. Child protection and out of home care: Policy, practice, and research connections Australia and New Zealand. Psychosocial Intervention 22: 175–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Theresa M., Sally N. Merry, Elizabeth M. Robinson, Simon J. Denny, and Peter D. Watson. 2007. Self-reported Suicide Attempts and Associated Risk and Protective Factors Among Secondary School Students in New Zealand. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 41: 213–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe. 2014. The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flick, Uwe, Ernst von Kardoff, and Ines Steinke. 2004. A Companion to Qualitative Research. New York: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Neil, Nigel Parton, and Marit Skivenes. 2011. Child Protection Systems: International Trends and Orientations. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert, Ruth, John Fluke, Melissa O’Donnell, Arturo Gonzalez-Izquierdo, Marni Brownell, Pauline Gulliver, Staffan Janson, and Peter Sidebotham. 2012. Child maltreatment: Variation in trends and policies in six developed countries. The Lancet 379: 758–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graneheim, Ulla H., Britt-Marie Lindgren, and Berit Lundman. 2017. Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today 56: 29–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackell, Melissa. 2016. Managing anxiety: Neoliberal modes of citizen subjectivity, fantasy and child abuse in New Zealand. Citizenship Studies 20: 867–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Clive, and Richard Denniss. 2005. Affluenz: When Too Much Is Never Enough. Sydney: Allen & Unwin. 240p, Available online: https://researchoutput.csu.edu.au/en/publications/affluenza-when-too-much-is-never-enough (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Harcourt, Bernard E. 2021. On Cooperationism: An End to the Economic Plague. Critical Inquiry 47: S90–S94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harcourt, Bernard E. 2023. Cooperation: A Political, Economic, and Social Theory. Columbia: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 2003. The fetish of technology: Causes and consequences. Macalester International 13: 7. Available online: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1411&context=macintl (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Hyslop, Ian. 2013. The ‘White paper for vulnerable children’ and the ‘Munro review of child protection in England’: A comparative critique. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 25: 4–14. Available online: https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.310155623198604 (accessed on 15 May 2023).

- Hyslop, Ian. 2017. Child Protection in New Zealand: A History of the Future. The British Journal of Social Work 47: 1800–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyslop, Ian. 2022. A Political History of Child Protection: Lessons for Reform from Aotearoa New Zealand. Bristol: Policy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hyslop, Ian, and Emily Keddell. 2018. Outing the Elephants: Exploring a New Paradigm for Child Protection Social Work. Social Sciences 7: 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irish, Leah, Ihori Kobayashi, and Douglas L. Delahanty. 2010. Long-term Physical Health Consequences of Childhood Sexual Abuse: A Meta-Analytic Review. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 35: 450–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Moana. 1987. The Maori and the Criminal Justice System, a New Perspective: He Whaipaanga Hou; Wellington: Policy and Research Division, Dept. of Justice. Available online: https://www.ojp.gov/pdffiles1/Digitization/108675NCJRS.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Jackson, Tim. 2016. Prosperity without Growth: Foundations for the Economy of Tomorrow. London: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- James, Oliver. 2007. Affluenza: How to Be Successful and Stay Sane. London: Vermilion. [Google Scholar]

- Jülich, Shirley. 2006. Views of justice among survivors of historical child sexual abuse:Implications for restorative justice in New Zealand. Theoretical Criminology 10: 125–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddell, Emily, and Gabrielle Davie. 2018. Inequalities and Child Protection System Contact in Aotearoa New Zealand: Developing a Conceptual Framework and Research Agenda. Social Sciences 7: 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keddell, Emily, and Ian Hyslop. 2019. Ethnic inequalities in child welfare: The role of practitioner risk perceptions. Child & Family Social Work 24: 409–20. [Google Scholar]

- Keddell, Emily, Gabrielle Davie, and Dave Barson. 2019. Child protection inequalities in Aotearoa New Zealand: Social gradient and the ‘inverse intervention law’. Children and Youth Services Review 104: 104383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, Steven L. 2010. The Ultimate History of Video Games, Volume 1: From Pong to Pokemon and Beyond … the Story Behind the Craze That Touched Our Lives and Changed the World. New York: Crown. [Google Scholar]

- Kraus, Michael W., Paul K. Piff, and Dacher Keltner. 2009. Social class, sense of control, and social explanation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 97: 992–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, Michael W., Stéphane Côté, and Dacher Keltner. 2010. Social Class, Contextualism, and Empathic Accuracy. Psychological Science 21: 1716–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landrigan, Philip J., and Anjali Garg. 2002. Chronic Effects of Toxic Environmental Exposures on Children’s Health. Journal of Toxicology: Clinical Toxicology 40: 449–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, Madeline. 2009. The Price of Privilege: How Parental Pressure and Material Advantage Are Creating a Generation of Disconnected and Unhappy Kids. HarperCollins e-books. [Google Scholar]

- Levine, Murray. 2000. The family group conference in the New Zealand children, young persons, and their families act of 1989 (CYP&F): Review and evaluation. Behavioral Sciences & the Law 18: 517–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lincoln, Yvonna S., and Egon G. Guba. 1985. Naturalistic Inquiry. New York and New Delhi: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lindstrom, Martin, Martin Lindström, and Patricia B. Seybold. 2003. Brandchild: Remarkable Insights Into the Minds of Today’s Global Kids and Their Relationships with Brands. London: Kogan Page. [Google Scholar]

- Māori Perspective Advisory Committee. 1988. Puao-teAta-tu (Day Break): The Report of the Ministerial Advisory Committee on a Māori Perspective for the Department of Social Welfare; Wellington: Department of Social Welfare. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/archive/1988-puaoteatatu.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Marsh, Peter. 1994. Partnership, Child Protection and Family Group Conferences-the New Zealand Children, Young Persons and Their Families Act 1989. Tolley’s Journal of Child Law 6: 109–15. [Google Scholar]

- May-Chahal, Corinne, and Pat Cawson. 2005. Measuring child maltreatment in the United Kingdom: A study of the prevalence of child abuse and neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect 29: 969–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayring, Philipp. 2014. Qualitative Content Analysis: Theoretical Foundation, Basic Procedures and Software Solution. Klagenfurt e-books: Available online: https://www.ssoar.info/ssoar/bitstream/handle/document/39517/ssoar-2014-mayring-Qualitative_content_analysis_theoretical_foundation.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Messner, Steven F., and Richard Rosenfeld. 2013. Crime and the American Dream. Belmont: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Mills, Charles Wright. 1959. The Sociological Imagination. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Social Development. 2012a. The White Paper for Vulnerable Children; Volume II; Wellington: New Zealand Government. Available online: https://library.nzfvc.org.nz/cgi-bin/koha/opac-detail.pl?biblionumber=3970 (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Ministry of Social Development. 2012b. The White Paper for Vulnerable Children; Volume I; Wellington: New Zealand Government. Available online: https://orangatamariki.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/Support-for-families/childrens-teams/white-paper-for-vulnerable-children-volume-1.pdf (accessed on 9 January 2023).

- Moffitt, Terrie E., Avshalom Caspi, Honalee Harrington, Barry J. Milne, Maria Melchior, David Goldberg, and Richie Poulton. 2007. Generalized anxiety disorder and depression: Childhood risk factors in a birth cohort followed to age 32. Psychological Medicine 37: 441–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nevin, Rick. 2000. How Lead Exposure Relates to Temporal Changes in IQ, Violent Crime, and Unwed Pregnancy. Environmental Research 83: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niman, Neil. B. 2014. The Allure of Games. In The Gamification of Higher Education: Developing a Game-Based Business Strategy in a Disrupted Marketplace. Edited by Neil B. Niman. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 69–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Michael. 2016. The triplets: Investment in outcomes for the vulnerable-reshaping social services for (some) New Zealand children. Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work 28: 9–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oleson, James C. 2007. ‘Drown the World’: Imperfect Necessity and Total Cultural Revolution. Unbound: Harvard Journal of the Legal Left 3: 19–116. [Google Scholar]

- Oleson, James C. 2023. A requiem for the Unabomber. Contemporary Justice Review 26: 179–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oranga Tamariki Act. 2017. Available online: https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1989/0024/latest/DLM147088.html (accessed on 6 January 2023).

- Parton, Nigel. 1985. The Politics of Child Abuse. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Parton, Nigel. 2014. The Politics of Child Protection: Contemporary Developments and Future Directions. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Pelton, Leroy H. 1978. Child abuse and neglect: The myth of classlessness. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 48: 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, Paul K. 2014. Wealth and the Inflated Self: Class, Entitlement, and Narcissism. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 40: 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, Paul K., Daniel M. Stancato, Stéphane Côté, Rodolfo Mendoza-Denton, and Dacher Keltner. 2012. Higher social class predicts increased unethical behavior. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109: 4086–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piff, Paul K., Michael W. Kraus, Stéphane Côté, Bonnie Hayden Cheng, and Dacher Keltner. 2010. Having less, giving more: The influence of social class on prosocial behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 99: 771–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pihama, Leonie, Ngaropi Cameron, and Rihi Te Nana. 2019. Historical Trauma and Whānau violence. Auckland: New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse, University of Auckland. [Google Scholar]

- Proietti-Scifoni, Gitana, and Kathleen Daly. 2011. Gendered violence and restorative justice: The views of New Zealand Opinion Leaders. Contemporary Justice Review 14: 269–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2000. Bowling alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Ridge, Tess. 2012. Children. In The Students Companion to Social Policy. Edited by Pete Alcock, Margaret May and Sharon Wright. New York: John Wiley & Sons Ltd., pp. 385–92. [Google Scholar]

- Roller, Margaret R., and Paul J. Lavrakas. 2015. Applied Qualitative Research Design: A Total Quality Framework Approach. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Savolainen, Jukka, Patrick J. Casey, Justin P. McBrayer, and Patricia Nayna Schwerdtle. 2023. Positionality and Its Problems: Questioning the Value of Reflexivity Statements in Research. Perspectives on Psychological Science 18: 1331–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schelbe, Lisa, and Jennifer M. Geiger. 2017. What Is Intergenerational Transmission of Child Maltreatment? In Intergenerational Transmission of Child Maltreatment. Edited by Lisa Schelbe and Jennifer M. Geiger. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreier, Margrit. 2012. Qualitative Content Analysis in Practice. New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Kate M., Katie A. McLaughlin, Don AR Smith, and Pete M. Ellis. 2012. Childhood maltreatment and DSM-IV adult mental disorders: Comparison of prospective and retrospective findings. British Journal of Psychiatry 200: 469–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, Elizabeth, and Sarah Monod de Froideville. 2020. From vulnerability to risk: Consolidating state interventions towards Māori children and young people in New Zealand. Critical Social Policy 40: 526–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkle, Sherry. 2011. The tethered self: Technology reinvents intimacy and solitude. Continuing Higher Education Review 75: 28–31. Available online: https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ967807 (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- UNICEF. 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. United Nations, Treaty Series, Issue. New York: United Nations. Available online: http://wunrn.org/reference/pdf/Convention_Rights_Child.PDF (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- UNICEF. 2020. Worlds of Influence: Understanding What Shapes Child Wellbeing in Rich Countries. New York: UNICEF. Available online: https://unicef-nz.cdn.prismic.io/unicef-nz/91c0a1c7-f7f8-42e9-8d96-9a0ff863ee87_Report-Card-16-Worlds-of-Influence-child-wellbeing.pdf (accessed on 10 July 2023).

- Vaithianathan, Rhema, Tim Maloney, Nan Jiang, Irene De Haan, Claire Dale, Emily Putnam-Hornstein, and Tim Dare. 2012. Vulnerable Children: Can Administrative Data Be Used to Identify Children at Risk of Adverse Outcomes; Report Prepared for the Ministry of Social Development. Auckland: Centre for Applied Research in Economics (CARE), Department of Economics, University of Auckland. Available online: https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/vulnerable-children/auckland-university-can-administrative-data-be-used-to-identify-children-at-risk-of-adverse-outcome.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Vrijheida, Martine, Maribel Casas, Mireia Gascona, Damaskini Valvi, and Mark Nieuwenhuijsen. 2016. Environmental pollutants and child health—A review of recent concerns. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health 219: 331–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Denise. 2016. Transforming the normalisation and intergenerational whānau (family) violence. Journal of Indigenous Wellbeing 1: 32–43. Available online: https://journalindigenouswellbeing.co.nz/media/2022/01/49.41.Transforming-the-normalisation-and-intergenerational-whanau-family-violence.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2023).

- Wilson, Nick, and John Horrocks. 2008. Lessons from the removal of lead from gasoline for controlling other environmental pollutants: A case study from New Zealand. Environmental Health 7: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Category | Theme | Code (Example) | Retrieved Section (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|

| From socio-cultural context to individualization of child maltreatment | Racism and historical roots | Monocultural laws and administration → Racism as the root cause | It is our view that the presence of racism in the Department is a reflection of racism which exists generally within the community. Institutional racism exists within the Department as it does generally through our national institutional structures. Its effects in this case are monocultural laws and administration in child and family welfare, social security or other departmental responsibilities. Whether or not intended, it gives rise to practices which are discriminatory against Māori people. (Māori Perspective Advisory Committee 1988, p. 24) |

| Impact of colonization | Throughout colonial history, inappropriate structures and Pakeha involvement in issues critical for Maori have worked to break down traditional Maori society by weakening its base-the whanau, the hapu, the iwi. It has been almost impossible for Maori to maintain tribal responsibility for their own people (Māori Perspective Advisory Committee 1988, p. 18) | ||

| Individualization and family responsibility | Family responsibility | The White Paper outlines a set of reforms that help to ensure that parents, caregivers, family, whānau and communities understand and fulfil their responsibilities towards children, as the single most critical factor in the care and protection of vulnerable children. (Ministry of Social Development 2012a, p. 2) | |

| Incompetent parents | Parents exert the most profound influence over the development of their children, for good or ill. Good parenting provides a protective environment for the early years, providing positive experiences that boost healthy brain development and a protective cocoon against sources of stress and harm. The vast majority of parents wish to do their best for their children, although not all have the knowledge, skills and resources to meet their development needs. A small minority does not have their best interests primarily in mind. There is a vast literature on the many ways that parents affect their children’s development. Much of the complexity in this literature can be summarised by focusing on two key topics: parent-child attachment and authoritative parenting. (Ministry of Social Development 2012a, p. 15) | ||

| Getting tough on abusers | Longer sentences | Amending the Crimes Act in 2011 to:

| |

| Surveillance | Information about at-risk children or families will be logged in a new information system and, if further action is needed, information will be accessed by relevant professionals so they can see the whole picture for a child. If a vulnerable child is referred to a community provider, a child and family worker, or government agency, all relevant information on the child will be available to them so they have the facts at their fingertips. (Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 7) | ||

| High-risk groups | Monitoring high-risk adults | The Government will extend and systematise existing arrangements for monitoring high-risk adults to include those subject to the proposed Child Abuse Prevention Order and other groups of high-risk adults, and to ensure that relevant information remains accessible over time. (Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 20) | |

| Child abuse prevention orders | New child abuse prevention orders (civil orders) will allow a judge to place restrictions in situations where an individual poses a high risk to a child or children in the future. Restrictions may include taking action to advise the parents or caregiver of the child and to remove the high-risk adult from the situation if appropriate. Another potential restriction is that when a child has been removed from a home due to serious child abuse at the hands of a parent, the existence of a child abuse prevention order could mean that another baby born into that situation is removed from that parent’s care. (Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 20) | ||

| Safe and loving home | Providing loving home as the most important responsibility | Ensuring we love, care and nurture all our children and young people throughout their lives is the most important task we have. This Strategy is our collective call to action. (DPMC 2019, p. 3) | |

| Good life for children | a good life for children and young people means being loved, happy, supported by their family and friends, and being connected to their whānau, communities, languages and cultures. Children and young people want to be accepted for who they are, listened to, and supported in their aspirations. (DPMC 2019, p. 11) | ||

| Social investment approach | Applying social investment approach | Child as human capital | A good start in life helps children to experience the best of childhood. The children of today are also the parents, workers and business and community leaders of tomorrow. To ensure future economic and social success, it is important that children are healthy, well nurtured and well educated so they are well equipped to assume these future roles. Investment in children can reduce the emergence of problems that have high social and fiscal costs. (Ministry of Social Development 2012a, p. 39) |

| Early identification as goal → Multiagency approach as tool → Social investment as foundation | The investment approach for vulnerable children will use data, evidence and analytics to:

| ||

| Vulnerability and vulnerable children | Focus on early identification of vulnerable children | Recent advances in research and technology mean we can now start to get ahead of the problem, identifying and helping some 20,000–30,000 vulnerable children and families, in many cases before the greatest harm occurs. (Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 5) | |

| Continuous focus on vulnerable children | In order to achieve greater equity, the Government has prioritised policies and initiatives to improve the wellbeing of children and young people who are living in poverty and disadvantaged circumstances, those of interest to Oranga Tamariki, and those with mental health or additional learning needs. (DPMC 2019, p. 60) | ||

| Risk assessment and early identification | Risk assessment by using big data | The Government will build new tools to help professionals identify which children are most at risk. A risk predictor tool has been tested by the Ministry of Social Development in conjunction with the University of Auckland and will be further developed to include a wider range of data. Using available information held by government, it has been possible to develop statistical criteria that help identify children at greater risk, based on information about them and their family circumstances. This approach could be used to guide professionals towards those children who are most vulnerable. (Ministry of Social Development 2012b, p. 10) | |

| Early intervention | Making sure that the right needs and risks are responded to at the right level, by identifying and intervening earlier with vulnerable children and their families/whānau who need intensive family support. (Ministry of Social Development 2012a, p. 115) | ||

| Child-centric service | Placing children at the center | The system does not place children at the centre. The current operating model is focused on process rather than on the needs of the child. Current legislation does not consistently support a child centred approach. (Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family 2015b, p. 15) | |

| Shift from service to child-centered | The system must shift from being primarily centred on the services, processes and administrative convenience of the agencies, to bringing the voice of children, young people and their families to the forefront. (Expert Panel_Modernising Child Youth and Family 2015b, p. 10) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nazari, H.; Oleson, J.C.; De Haan, I. Problematizing Child Maltreatment: Learning from New Zealand’s Policies. Soc. Sci. 2024, 13, 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040193

Nazari H, Oleson JC, De Haan I. Problematizing Child Maltreatment: Learning from New Zealand’s Policies. Social Sciences. 2024; 13(4):193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040193

Chicago/Turabian StyleNazari, Hamed, James C. Oleson, and Irene De Haan. 2024. "Problematizing Child Maltreatment: Learning from New Zealand’s Policies" Social Sciences 13, no. 4: 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040193

APA StyleNazari, H., Oleson, J. C., & De Haan, I. (2024). Problematizing Child Maltreatment: Learning from New Zealand’s Policies. Social Sciences, 13(4), 193. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci13040193