Abstract

Under the influence of international trade, labor flow not only exists in the waves of international labor migration but is also embodied in international products and services. This paper focused on members of the China–Africa Cooperation Forum (FOCAC). We computed and analyzed the sectoral embodied labor transfer between China and Africa from 2000 to 2015 based on the Multiregional Input-Output Method. Our results are as follows: (1) Both China and Africa play roles as labor suppliers in the global supply chain. By ameliorating the trade structure, both China and Africa can better utilize their labor surplus. (2) China and Africa share complementarity in sectoral labor allocation. In short, the embodied labor transfer via international trade between China and Africa has, to some extent, relieved the labor shortage on both sides. (3) Africa has transformed into a net exporter of industrial labor since 2011. By analyzing the embodied labor flow from the global perspective, this paper beats a new path in depicting the effect of international trade on labor allocation, enriches the evaluation of embodied labor transfer between China and Africa, and also provides a beneficial supplement to Multiregional Input-Output analysis in the field of factor flows.

1. Introduction

International trade can boost economic growth by stimulating domestic productivity and competitiveness (Chang et al. 2009; Edwards 1998; Sakyi et al. 2014), facilitating global flow and reallocation of production factors such as capital, energy, and labor (Feenstra 2015; Goldberg and Pavcnik 2007; Matsumoto 2019). Factor endowment has long been the core of international trade, and labor, being one of the essential and special factors, shares an intricate relationship with international trade. On one hand, according to the theory of international trade based on factor endowment, nations rich in labor supply will specialize in the production and exportation of labor-intensive products (Fisher 2011; Roy 1967). Nations with different comparative advantages show different patterns in labor use, and research about the effect of trades on employment has blossomed rapidly (Auer and Fischer 2010; Balsvik et al. 2015; Bernard et al. 2006; Fatima and Khan 2019; Jiang 2015). On the other hand, opening up to international trade means a physical multi-regional and multi-industrial labor flow, hence a global reallocation of factor endowment (Autor et al. 2013; Costa et al. 2016).

The world today is a world of the intertwined, reciprocal, and migration (Cepeda-López et al. 2019). As statistics from the ILO (International Labour Organization) have shown, among the 232 million people who live outside their birth nations, nearly 65% are migrating workers. Mass labor flow has, in part, adjusted regional economic development and cultural structures, yet it does not necessarily accompany a promotion in personal welfare. Sometimes, it might even induce substantial costs for the migrators (Kasimis 2008; Rogaly 2008; Rye 2018), especially in developing countries. The friction in labor markets usually causes immense flowing costs (Artuc et al. 2015) as well as forced migration under limited freedom and extreme destitution, as described in the Human Development Report of UNDP (the United Nations Development Programme) and the World Bank Report. Furthermore, geographic flow means commuting costs, which can add to the stress on global resources and the environment.

In fact, international trade itself can trigger an embodied labor flow, which happens to be a factor with relatively high flowing costs. Embodied labor flow is, rather than in a geographic sense, a transfer and migration embodied in the production and consumption links of products and services that are traded across the globe. In this paper, we define the term embodied labor as the sum of labor invested, both directly and indirectly, in the production of one certain product or service. The term represents global labor use related to certain products and services, and thus we can depict the overall picture of whole-chain labor use from production to consumption. Concepts such as embodied energy (Camaratta et al. 2020; Chen and Chen 2011; Costanza 1980; Ji et al. 2020b, 2022; Wu et al. 2020), virtual land (Han and Chen 2018; Han et al. 2015; Ji et al. 2020a, 2023; Würtenberger et al. 2006), and embodied greenhouse gas emissions (Davis and Caldeira 2010; Huang et al. 2019; Ji et al. 2020c; Long et al. 2018; Peters and Hertwich 2006; Su et al. 2013) have been widely applied in international trade analysis.

However, research about trade-induced embodied labor flow is still rarely seen. Though the earliest study of similar ideas can date back to Bezdek’s research in 1974 about human resources, energy, and freeway trust funds, it was not until 2014 that specific and systematic labor footprint tracing sprang up. Alsamawi et al. (2014) developed a social footprint computing method based on the Input-Output model. From the consumption view, they divided the world into “owners”—those who enjoy other nations’ labor supply—and “servants”—those who supply their labor resources to other nations. They held that labor mainly flowed from developing countries to developed ones. Since then, the idea that trades could realize labor flow has slowly been accepted and rapidly developed abroad. Simas et al. (2014) quantified the relativity of bad labor conditions with international trade from the production side, differentiated the labor footprints of six specific dire labor conditions, including occupational health damage, employment of a vulnerable group, gender inequality, low-skilled employment and so on in the global production chain across seven regions. Their work revealed that labor suffering from such bad conditions mainly flows from developing countries to developed regions. Asia and Africa, in particular, have seen the most labor outflows. This research provided a brand-new perspective on revealing the social influence of globalization.

After that, Simas et al. (2015) computed the energy and labor embodied in the EU’s imports from the consumption side and found that the EU’s embodied labor import significantly overshadows its export, and about 30% of its labor import is low-skilled labor. Gómez-Paredes et al. (2015) took India as an example to evaluate the labor problems behind different production activities across the whole supply chain, covering collective bargaining, forced labor, child labor, gender inequality, hazardous employment, and social security. This analysis elaborated on the significance of the labor footprint in depicting social sustainability.

Hardadi and Pizzol (2017) calculated the social footprint based on ILO’s statistics of employment, working time, salary, occupational accidents, and unemployment, trying to quantify their impacts on productivity and social welfare. Their work greatly broadened the social horizon of theoretical analysis and achieved a milestone in social lifecycle evaluation. Alsamawi et al. (2017) calculated the occupational safety and health footprint of labor embodied in the consumption side to derive the number of accidents behind the global supply chain, calling for an urgent improvement of labor conditions.

Research combining the labor footprint and other economic indexes have also provided many constructive conclusions. Rocco and Colombo (2016) proposed the Bioeconomic Input-Output model based on the life cycle concept, internalizing labor into economic activities as a new production sector. Their research showed that the internalization of labor has changed the sum of energy embodied in products and services. Sakai et al. (2017) computed Britain’s emission and employment footprint, trying to figure out their relationship, driving factors, and sectoral components. This research provided a new angle for understanding the relationship among trading, environment, and development.

Based on the existing literature, we find that, for one, research on embodied labor flow, compared with that on other embodied factors (for example, energy and water), is still relatively new and booming. For another, there has not been any embodied labor flow research on two specific economies under economic globalization so far. All current and past research focuses on the state level rather than differentiating down to sectors. In addition, our limited documentary tracing has shown that there has not been any research on the embodied labor transfer relationship between China and Africa.

As populous economies, labor is of great significance to the economic development of China and Africa. By participating in global trade, China increases its global labor supply (Xu et al. 2018). However, with the deepening of the Reform and Open, the climbing of labor costs, and the depletion of its demographic dividend, China calls for an impending structural revolution. In Africa, over 50% of the population works as farmers, and the proportions involved in other occupations are all significantly lower than the global rate as reported by the ILO. Labor is a restraint on Africa’s economic development in two ways. First, Africa suffers from both a lack of labor and a relatively low-skilled labor supply. Second, compared with other production factors such as capital, land, and technology, the formation and development of labor requires a longer cycle and harsher conditions, which is more likely to become a potential bottleneck in Africa’s development. Existing discussions about China’s impact on Africa’s labor market in the context of international trade mainly focus on two topics: institutional impact and employment opportunities. For instance, Adolph et al. (2016) proposed a theoretical assumption called the “Shanghai Effect”, claiming that China’s exportation might affect Africa’s labor standard. Some researchers hold the idea that the massive inflow of cheap Chinese textiles and household electronic appliances has resulted in the shrinkage of relevant African sectors and mass unemployment (Peh and Eyal 2010; Kaplinsky and Morris 2008; Konings 2007).

According to World Development Indicators, the population growth rate of Sub-Sahara Africa reached 2.542% in 2022, while for EU countries this indicator is only 0.043%. Considering a broader global background with anticipated rapid population growth in Africa and the depopulation trends observed in Europe, as well as the increasing influence of China in the Silk Road Economic Belt region and even in the world, the future resolution of international labor flow will be paramount (Cepeda-López et al. 2019). Both China and Africa have been comprehensively and significantly affecting the quantity and spatial distribution of global production factor flow, and labor is undoubtedly an indispensable link in the chain. We estimated sectoral embodied labor transfer of trade under the Multiregional Input-Output (MRIO) framework, aiming to evaluate the sectoral labor allocation between China and Africa, to respond to existing discussions and to provide a new angle for both parties’ industrial cooperation and labor structural betterment. A discussion on the impact of embodied labor flow on labor allocation within the big picture of economic globalization will not only enrich the field of embodied factor studies but also beat a new path in terms of labor issues between China and Africa.

2. Methods and Data

2.1. Methods

Multiregional Input-Output (MRIO) analysis reflects the relationship between intermediate input and final demand among all regions and sectors within the global supply chain (see Appendix B for more details about the MRIO method). Exportation of a nation is seen as an inflow of other nations’ intermediate input and final demand. Importation is treated as an outflow of other nations’ intermediate input and final demand. Based on the MRIO and the employment sheet of the corresponding region, we can systematically compute labor use via global trade to arrive at the total sum of labor flow induced by the final demand embodied in the global supply chain. When simulating the global economy with the MRIO accounts, we can view the world as a world of m regions, each with n sectors.

Based on the MRIO balance, the total production of region s sector j () consists of two different sections: its production of intermediate input toward other regions and sectors () and its production applied in final demands of other regions and factors (). The balancing equation is as follows:

Rewrite the equation in the matrix form:

The matrix can be expressed as follows:

Then we can get the key equation:

refers to the total production matrix (), refers to intermediate input matrix (), refers to the sectoral input coefficient matrix (), and is the matrix of final demand ().

The total labor embodied in final demand equals direct labor intensity times total production, the equation being:

Hence, the embodied labor flow from region r to region s equals:

refers to total employment (), is the diagonal matrix of total production matrix (), and is the Leontief inverse matrix and reflects the direct and indirect input required in each unit of the final demand ().

We can calculate the labor requirement embodied in the final demand of region s, the labor embodied in the final demand (LEF):

Likewise, the labor force (LF) of region s equals:

Thus, the labor inflow embodied in the final demand (LEFI), the labor outflow embodied in final demand (LEFE), and the net labor inflow embodied in final demand (LEFTB) of region s are as follows:

2.2. Data Source

The Eora database has the most extensive coverage of African nations as well as a long time-span, both facilitating a consistent and comprehensive analysis of the embodied labor transfer between Africa and China. In this paper, we matched the members of the FOACA and those within the Eora global MRIO database to select China and 50 African nations (in later parts the term “African countries” refers to all 50 African participants, and the country list is displayed in Table A1 in Appendix A) as our samples, covering a period of 16 years from 2000 to 2015. These 50 African nations cover all four income levels—high income, higher-middle income, lower-middle income, and low income. Geographically, these 50 nations cover all inland, coastal, and island types.

The International Labor Organization (ILO) Database supplied us with labor data of the three industries of the major nations, yet lacks detailed sectoral statistics for most African countries. Taking data availability into consideration, we bracketed the origin labor data into three categories: Agriculture labor, Industrial labor, and Service labor. The sectoral labor employment is derived by comparing and merging the ILO and IMF databases, with a unit of thousand. The Eora global MRIO database consists of 189 regions and 26 sectors. To match the labor employment data of the three industries, we bracketed the 26 sectors of the Eora Input-Output table into Agriculture, Industry, and Service correspondingly.

3. Results

3.1. Labor Force and Embodied Labor in Final Demand of China and Africa

3.1.1. Labor Force and Labor Use of China and Africa

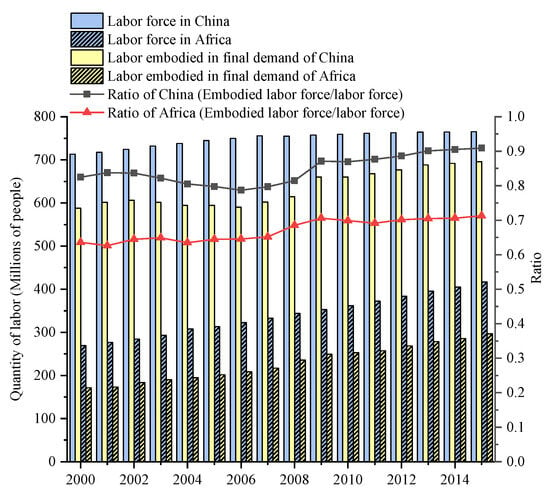

Figure 1 depicts the labor force (LF) and labor use (LEF) of China and Africa from the year 2000 to 2015, the latter being the total labor embodied in the final demand. Apart from the above, we could also calculate each nation’s embodied-employment labor ratio (LEF/LF). The ratios of both China and Africa revealed a climbing trend, which gradually approached 1. This indicated a mounting desire for labor from other regions to meet their final demand.

Figure 1.

LF, LEF, and the ratio of LF/LEF in China and Africa.

Firstly, according to the total amount and ratio, we found that both economies’ labor force overweighed their embodied labor. This means that they had more labor resources than the labor used in their final demand, by reference acting as labor suppliers within the global value chain, which is consistent with previous research (Simas et al. 2015; Alsamawi et al. 2014). Moreover, China exceeded Africa both in labor force and embodied labor in demand. During our research period, the labor force in China remained relatively stable within the range of 712.98 to 764.96 million. Embodied labor in China’s final demand showed a mild climbing trend with fluctuations, reaching a growth peak of 7.38% between the years 2008 and 2009. Africa revealed a powerful growing tendency, for its labor force and embodied labor in demand were increasing year by year with a growth rate of 54.59% and 73.32%, respectively.

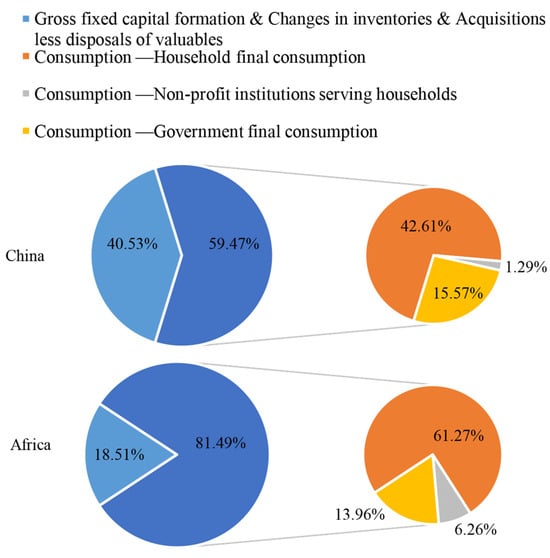

Figure 2 reveals the sectoral proportion of labor embodied in the final demand (see the details in Table A2 and Table A3 in Appendix A). The final demand can be classified into two parts: final consumption and others (such as total fixed assets and investments). Final consumption consists of three categories, namely household final consumption, government final consumption, and non-profit institutional serving households’ consumption. During the study period, labor embodied in the final consumption made up 55~65% of the total embodied labor with a steady decrease. As for Africa, the rate was over 80% with a decreasing trend at the same time, although the decreasing rate was lower than that of China. In both economies, among all embodied labor in final consumption, the household final consumption contributed the most to the proportion, accounting for more than 70%. Compared to China, Africa utilized more labor to meet its needs for household final consumption.

Figure 2.

Average proportion of embodied labor in final demand of China and Africa from 2000 to 2015.

3.1.2. Sectoral Contribution of Labor Force and Embodied Labor of China and Africa

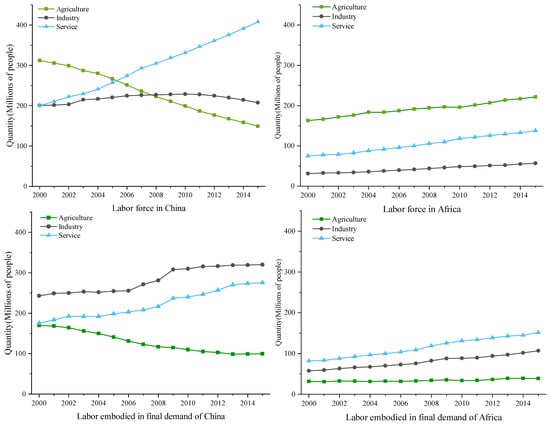

Figure 3 reveals the sectoral contribution of the labor force and embodied labor of China and Africa. China’s total labor force has remained stable, yet the sectoral structure has transformed significantly. Labor force in the agricultural sector plunged while that in the service sector soared. During the years 2005 and 2006, the labor force in the agricultural sector first shrank to a size smaller than that in service. Then in the year 2008, it was even lower than the industrial sector, the lowest of all three. Since 2005, the service sector has become the sector consuming the most substantial fraction of the total labor force. Until 2015, the sectoral proportions of the labor force in the agricultural sector, industrial sector, and service sector were 20%, 27%, and 53% respectively. Among all the three sectors of China, the industrial sector had the largest amount of embodied labor, followed by the service sector and agricultural sector in that order. Embodied labor in the industrial sector and service sector climbed steadily while that in the agricultural sector kept decreasing. Until 2015, sectoral proportions of embodied labor in the agricultural sector, industrial sector, and service sector were 14%, 40%, and 46% respectively.

Figure 3.

Sectoral structure of labor force and embodied labor in China and Africa.

As for Africa, among all three sectors, the agricultural sector contributed to the majority of the labor force, followed by the service sector and the industrial sector. The labor force in the agricultural sector took up about 60% at its peak. The quantities of labor in the service and industrial sectors were relatively low, yet climbing steadily. As for the sectoral contribution of labor use embodied in the final demand, the service sector ranked first among all three sectors of Africa, followed by the industrial sector and agricultural sector. Labor embodied in the agricultural sector mostly remained stable, while that of the other two sectors increased consistently.

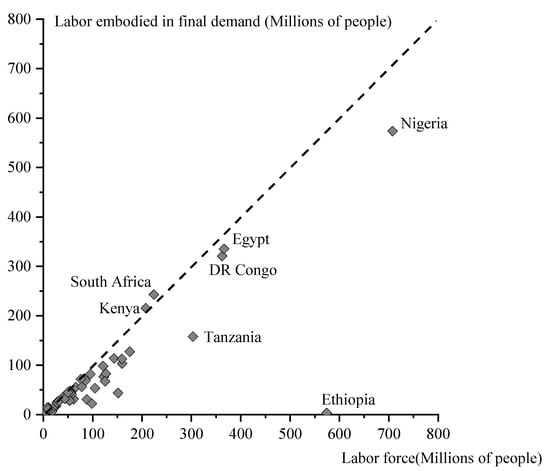

3.1.3. Total Labor Force and Embodied Labor of African Countries

In Figure 4, the x-axis and y-axis reflect the total labor force and total embodied labor in final demand of the 50 African countries from the year 2000 to 2015. As depicted in the figure, most African countries have a relatively small scale of both labor force and labor use, all less than 200 million. Nigeria, Egypt, DR Congo (the Democratic Republic of Congo), South Africa, Kenya, and Tanzania stand out from the crowd. The quantities of South Africa’s and Kenya’s embodied labor in their final demand surpass their own labor force, by 18.99 and 7.76 million, respectively. Nigeria, Egypt, DR Congo, and Tanzania all have a domestic labor force higher than labor embodied in the final demand, especially Nigeria and Tanzania, with a surplus of 134.12 and 145.26 million, respectively. Although Ethiopia enjoys a large-scale domestic labor force, its tiny labor use is absorbed in the final demand, indicating a giant gap between a large labor supply and a small labor demand.

Figure 4.

Total labor force and embodied labor of African countries from 2000 to 2015.

3.2. The Feature of Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Africa

3.2.1. Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Africa

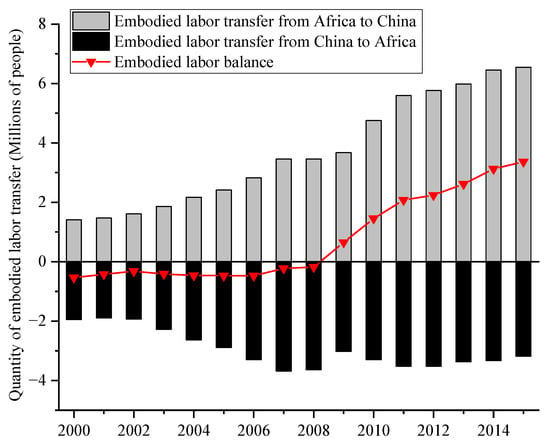

Figure 5 reveals the total and net flow of embodied labor transfer from China and Africa to each other derived by their final demand (see Table A4 in Appendix A for details). The result shows a turning point in 2008. Before 2008, embodied labor flow from China toward Africa outstripped that of vice versa, meaning that Africa utilized more of China’s labor to meet its final demand than China utilized the labor of Africa. After 2008, China transformed into a net importer of embodied labor, which means that China mobilized more African labor to meet its demand. This phenomenon can be partly attributed to the steady increase of net labor inflow of all three sectors from Africa toward China. The exportation of embodied labor from China toward Africa showed a climbing tendency from 2000 to 2008, with a significant drop affected by the global financial crisis in 2009, a short rebound, and finally a faint drop again during 2012~2015. From 2000 to 2015, the labor embodied in China’s imports from Africa mounted consistently with considerable growth, especially during the years 2009~2010, with a growth rate reaching 25%. During our study period, China realized a net labor import and the net amount continued to increase.

Figure 5.

Embodied labor transfer between China and Africa from 2000 to 2015.

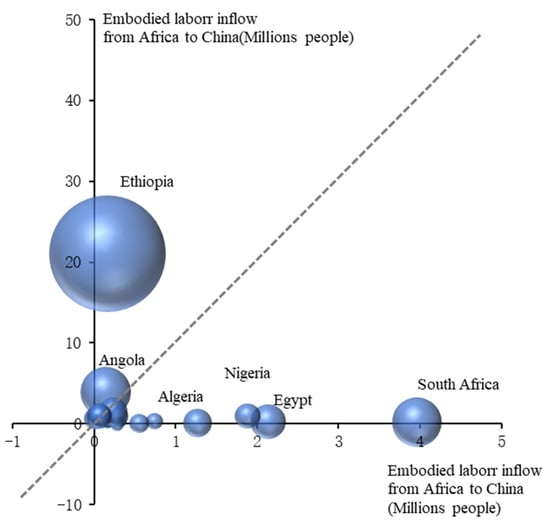

Figure 6 depicts the embodied labor transfer between China and the African countries. The bubbles represent the fifty African countries. The x-axis and y-axis reflect the net outflow of embodied labor from China to Africa and the net inflow of embodied labor from Africa to China. The size of the bubble symbolizes the amount of net embodied labor flow. As depicted in the picture, the relationship between China and African countries varied significantly. South Africa, Egypt, Nigeria, and Algeria were all giant net importers of embodied labor. China exported 3.96, 2.13, 1.89, and 1.27 million embodied labor toward these four countries, respectively. Ethiopia and Angola are great net exporters, especially Ethiopia, which had a shocking 21.06 million of net embodied labor outflow toward China during the sixteen years, much greater than any other African country. By scale, the biggest embodied labor flow appeared for the net exporters Ethiopia and Angola, and the net importer South Africa.

Figure 6.

African countries’ total inflow/outflow of embodied labor to/from China.

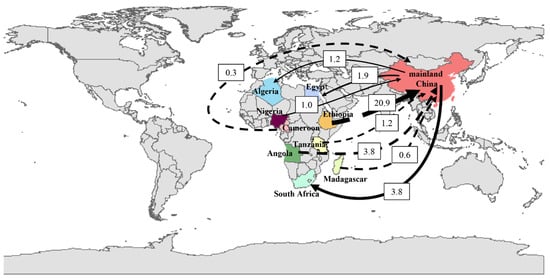

Figure 7 depicts the labor transfer between China and the African countries with prominent embodied net labor flows on a map (unit: million) in order to capture the geographical characteristics. Obviously enough, most of Africa’s net inflow and outflow of labor are coastal countries, except for Ethiopia. As shown in the picture, South Africa, Egypt, and Algeria were all stable net importers, bearing 3.8, 1.9, and 1.2 million, respectively, of China’s embodied labor outflow during the 16 years, while Ethiopia, Angola, and Tanzania were the net exporters, supplying China with 20.9, 3.8, and 1.2 million, respectively, of embodied labor during 2000 to 2015. Ethiopia was the paragon of all net exporters, whose outflow outstripped all others, mounting from about 0.6 million in 2000 to about 3.5 million in 2015, an almost six times increase in size. Recently, more and more countries have transformed into China’s net exporters, Cameroon, for example.

Figure 7.

Geographic distribution of net embodied labor flow between China and African countries.

3.2.2. Sectoral Distribution of Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Africa

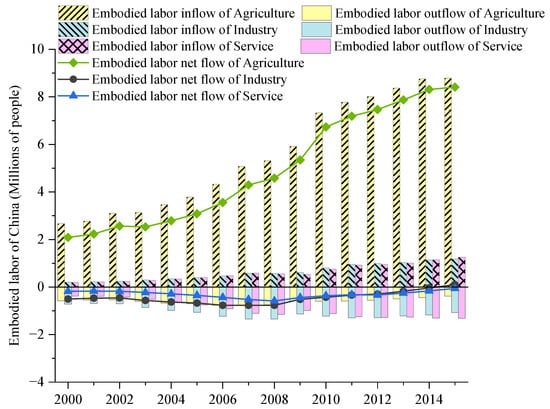

Figure 8 reflects the changes in the sectoral distribution of embodied labor transfer from 2000 to 2015. From the sector distribution of embodied labor transfer, China and Africa differentiate in labor utilization. For one thing, China’s embodied labor exportation toward Africa mainly assembled in the industrial and service sector, with the industrial sector always playing a leading role. The service sector, on the other hand, overtook the agricultural sector in 2005 and the industrial sector in 2012, and finally became China’s largest source of embodied labor outflow toward Africa. Both the total amount and the proportion of embodied labor flow in the agricultural sector have declined considerably, indicating that Africa is in massive need of China’s industrial and service labor to meet its demand. For another, labor in the agricultural sector took up the largest proportion of embodied labor flow from Africa to China, while the embodied labor flow in the industrial sector and service sector were of a relatively similar size.

Figure 8.

Trend of sectoral distribution of embodied labor flow with Africa.

The net flow of labor between China and Africa derived by the final demand was from Africa to China, which can be mainly attributed to the huge net supply of embodied labor in the agricultural sector from Africa to China. In other words, China has mobilized an enormous amount of Africa’s agricultural labor to meet its final demand. As for the industrial and service sectors, China acted as a net embodied labor exporter toward Africa, indicating that Africa was utilizing China’s industrial and service labor to meet its final demand. Since 2008, China’s net outflow of embodied labor in the industrial and service sectors has been gradually reducing, while the labor supply of the industrial and service sectors has been increasing in the global value chain. Especially after 2012, embodied labor flow in the service sector was a net flow from Africa to China, indicating a turning point in the final demand, China’s utilization of African service labor exceeded Africa’s utilization of Chinese service labor.

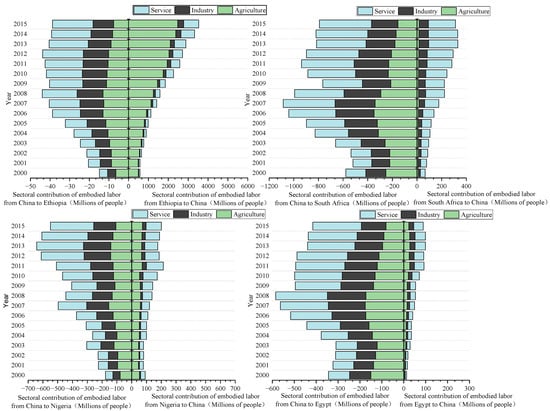

3.2.3. Sectoral Contribution of Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Typical African Countries

To further explore the sectoral feature of embodied labor transfer between China and African countries, we selected the four examples with the most remarkable scale—Ethiopia, South Africa, Nigeria, and Egypt to analyze in detail their respective total amounts and sectoral structures of their embodied labor flows with China (as depicted in Figure 9). Firstly, we calculated the embodied labor transfer between China and Egypt, South Africa, Nigeria, and Ethiopia between 2000 and 2015. We found that, for Egypt, Nigeria, and South Africa, China acted as a net labor exporter, while for Ethiopia, China acted as a net importer. The flow of embodied labor transfer between China and South Africa and that between China and Egypt shared similar trends: the net labor inflow into China mounted since 2000, reaching the apex in 2013 and dropped slightly in the following two years. Meanwhile, China’s labor inflow to Egypt and South Africa showed a decreasing trend, hitting the bottom in 2003 and 2009 and reaching the peak in 2007 and 2008. The embodied labor flow from Nigeria into China kept climbing before 2011, then declined, and slowly went up again after 2013. The embodied labor flow from China to Nigeria mounted with fluctuations, reaching the peak in 2013 and dropping slightly afterward. Ethiopia’s embodied labor inflow to China far outnumbered all three countries with a rapid growth rate over five times theirs, while China’s labor flow into Ethiopia was relatively low, although mounting.

Figure 9.

Sectoral contribution of embodied labor transfer between China and Ethiopia, South Africa, Nigeria, and Egypt.

Secondly, we analyzed the sectoral contribution of embodied labor transfer. During the study period, the proportion of China’s embodied labor flowing into the four countries increased gradually in both the industrial sector and the service sector. While the proportion of labor in the agricultural sector climbed first and then fell, the embodied labor flow from South Africa to China mainly remained in the industrial and service sectors. The flow from Egypt, Nigeria, and Ethiopia to China concentrated on the agricultural sector, though the flow of the industrial and service sectors was slowly climbing.

This result is quite consistent with the previous research of Eisenman (2012) who holds the view that China’s comparative advantage in capital-intensive production and Africa’s abundant natural resource endowments are two of the key factors for China-Africa trade. Agriculture in Ethiopia has long been occupying the largest proportion of embodied labor outflow. Though the industrial and service sectors may have low embodied labor outflow, the growth rate was considerable. This phenomenon denotes the fact that China has utilized a gigantic amount of Ethiopia’s agricultural labor, and its reliance on Ethiopia’s industrial and service labor is also mounting. South Africa was the largest embodied labor net importer, with the flowing trend of its three sectors intercepting one another with time. The embodied labor inflow in the agricultural sector decreased with fluctuation while the inflow of the other two sectors increased with fluctuation. Net embodied labor inflow in the service sector reached the same level as that of the industrial sector at around 2011 and then outstripped the latter after 2011, denoting that Africa’s demand for China’s agricultural labor was declining while that for China’s industrial and service labor was ascending.

4. Sectoral Labor Allocation behind the Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Africa

4.1. Complementarity of Embodied Labor Transfer between China and Africa

The embodied labor flow between China and Africa can in part reflect their complementarity of sectoral labor utilization. On the one hand, Africa supplied more agricultural labor resources, which exceeded its own final demand, and has realized a net outflow of embodied agricultural labor to China. In other words, China mobilized Africa’s surplus agricultural labor. On the other hand, through global trade, Africa was able to take advantage of China’s vast supply of industrial labor to relieve its own massive demand in the early stage of industrialization.

This phenomenon was the result of a rational choice, tallying with the comparative advantages of both sides. Africa had a small demand for agricultural resources, with a supple stock and a comparative advantage in production factors. Meanwhile, its industry—especially manufacturing—lagged behind and was in dire need of medium- and high-level industrial capacity to meet the needs of domestic production and consumption. The labor transfer embodied in trade provided Africa with such an opportunity to utilize China’s industrial labor resources to realize its own industrialization, which not only ameliorated its own employment status and addressed its shortage of industrial and service labor supply, but also alleviated China’s shortage of agricultural labor. As for the sectoral embodied labor transfer trend, although agriculture ranked first among all Africa’s three sectors in embodied labor outflow, the other two sectors—industry and service—both showed a climbing trend. The service sector, in particular, even became a net exporter of labor to China after 2012. This was strong evidence of Africa’s growing capacity to export industrial products and China’s increasing use of African labor in the service sector. Therefore, the labor market and industrialization level of Africa was not hampered. Quite the opposite; by the labor flow embodied in trade, both China and Africa could exert their comparative advantage and realize labor allocation betterment.

4.2. China’s Utilization (Amelioration) of Africa’s Labor Surplus (Shortage)

Trade accompanied a massive embodied labor flow. Agriculture labor occupied a significant proportion of the embodied labor transfer between China and Africa. Via trade, Africa’s surplus agricultural labor resources were utilized, while its labor shortage in the industrial and service sectors was relieved.

We further derived the sectoral contribution of the net inflow (outflow) of embodied labor between China and Africa to the utilization of labor surplus (shortage) in Africa from 2000 to 2015. Such a contribution ratio could be calculated through the following equation:

Table 1 reveals China’s total and sectoral contribution ratio of utilization (amelioration) of Africa’s labor surplus (shortage). The embodied labor transfer between China and Africa could make use of Africa’s redundant agricultural labor, alleviate its labor shortage in the industrial and service sectors, and show a tendency to improve Africa’s industrial and service development. As can be seen from Table 1, both the total amount of Africa’s surplus labor utilized by China and the ratio of Africa’s agricultural sector mounted consistently, while that of the industrial and service sectors first climbed and then fell. Until 2015, China utilized 4.64% of Africa’s labor surplus. China’s net imports of Africa’s embodied agricultural labor as well as the contribution ratio of the agricultural sector kept climbing and the ratio reached 6.81% in 2015. The contribution ratio of the industrial sector reached its peak in 2008 then plunged for a while. China’s contribution to Africa’s service sector turned negative as a result of its net imports of embodied labor from Africa in 2011.

Table 1.

Contribution ratio of China’s utilization (amelioration) of Africa’s labor surplus (shortage) through embodied labor transfer.

5. Conclusions and Implications

5.1. Conclusions

Labor flow embodied in trade directly reflects the industrial development and employment status of relevant nations, and exerts a significant impact on labor flow and allocation among countries. We applied the MRIO method to calculate the embodied labor transfer of the agriculture, industrial, and service sectors between China and fifty African participants in FOCAC from 2000 to 2015. According to our results, we arrived at the following conclusions:

- Both China and Africa play roles as labor suppliers in the global value chain. By promoting trading structure and rationalizing economic layouts, both China and Africa can provide employment opportunities to their surplus labor without the need of geographic migration. The embodied labor flow via trade can cast new lights on exerting both economy’s comparative advantages and realizing optimal cross-regional and cross-sectoral labor allocation.

- China and Africa share certain complementarity in cross-sectoral labor usage, which, to some extent, can alleviate the bottleneck of labor they face in their economic development. Trade is a choice based on the comparative advantages of both sides. China’s mass utilization of Africa’s redundant agricultural labor in the global production chain can not only alleviate Africa’s employment plight but also relieve its own predicament of a constantly decreasing supply of agricultural labor. Meanwhile, providing Africa with China’s industrial and service labor can make up for the current lack of industrial and service labor supply in Africa to some extent.

5.2. Implications

Based on our study, we could arrive at the following inspirations:

Firstly, reallocation of labor does not necessarily mean cross-regional geographic migration. It can also be achieved by rationalizing economic industry layout, improving trade structure, and adjusting the embodied labor flow via trade. Since labor is one critical production factor, migration is an important yet not indispensable way to optimize resource allocation. Moreover, embodied labor flow could avoid the economic and social burdens such as commuting, living, and emotional costs that would have been inevitable in cross-regional labor migration.

Secondly, this study provides a supplement to existing studies on the effect of trade on Africa’s labor market, offering a new lens to evaluate such impact. Apart from studying the impact on labor standards and employment, this paper has proven that trade benefits both economies by advantage complementarity and labor allocation betterment. Trading with China not only proffers vast employment opportunities for Africa’s immense agricultural labor but also helps China harness Africa’s demographic dividend to tackle its own predicament of decreasing labor.

Lastly, based on our analysis of the embodied labor flow between China and Africa, we state that the allocation of labor resources between China and Africa can be further optimized. While strengthening the trade link with China, the optimized transfer of embodied labor in the agricultural, industrial, and service sectors should be guided according to the characteristics of each sector. China should maintain intimate contact with Africa in agricultural trade to fully utilize its advantages in arable land and labor resources, raise the added value of industrial products, strengthen the link in service trade, and increase service export to tackle the labor surplus in China’s service sector and labor shortage in Africa’s corresponding sector.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.J.; methodology, X.J. and Y.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, X.J., Y.L. and J.Y.; formal analysis, X.J. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, X.J. and Y.L.; data curation, Y.L.; writing—original draft preparation, X.J. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, J.Y. and X.J.; visualization, Y.L.; supervision, X.J.; project administration, X.J.; funding acquisition, X.J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was jointly supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant No. 71973008; the Major Special Program of Social Science Foundation of China, grant No. 22VMG017.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original datasets are all obtained from open access sources, which are all described in detail in the paper. Here are the weblinks: The Eora Global MRIO Database: https://worldmrio.com/eora/ (accessed on 12 September 2020). The International Labor Organization Database: https://www.ilo.org/global/statistics-and-databases/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 12 September 2020).

Conflicts of Interest

Author Yifang Liu was employed by Global Energy Interconnection Group Co., Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest. The Global Energy Interconnection Group Co., Ltd. had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Economic and geographical indicators of fifty African participants in FOCAC.

Table A1.

Economic and geographical indicators of fifty African participants in FOCAC.

| GDP Ranking | Country | Per-Capita Income | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nigeria | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 2 | Egypt | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 3 | South Africa | High-middle income | Coastal |

| 4 | Algeria | High-middle income | Coastal |

| 5 | Angola | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 6 | Morocco | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 7 | Sudan | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 8 | Ethiopia | Low income | Inland |

| 9 | Kenya | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 10 | Ghana | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 11 | Tanzania | Low income | Coastal |

| 12 | Tunisia | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 13 | Cote d’Ivoire | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 14 | DR Congo | Low income | Coastal |

| 15 | Cameroon | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 16 | Libya | High-middle income | Coastal |

| 17 | Rwanda | Low income | Inland |

| 18 | Zambia | Low-middle income | Inland |

| 19 | Zimbabwe | Low income | Inland |

| 20 | Senegal | Low income | Coastal |

| 21 | Mozambique | Low income | Coastal |

| 22 | Botswana | High-middle income | Inland |

| 23 | Gabon | High-middle income | Coastal |

| 24 | Mali | Low income | Inland |

| 25 | Mauritius | High-middle income | Island |

| 26 | Namibia | High-middle income | Coastal |

| 27 | Chad | Low income | Inland |

| 28 | South Sudan | Low income | Inland |

| 29 | Burkina Faso | Low income | Inland |

| 30 | Madagascar | Low income | Island |

| 31 | Guinea | Low income | Coastal |

| 32 | Congo | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 33 | Benin | Low income | Coastal |

| 34 | Rwanda | Low income | Inland |

| 35 | Niger | Low income | Inland |

| 36 | Somalia | - | Coastal |

| 37 | Malawi | Low income | Inland |

| 38 | Mauritania | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 39 | Eritrea | - | Coastal |

| 40 | Sierra Leone | Low income | Coastal |

| 41 | Togo | Low income | Coastal |

| 42 | Liberia | Low income | Coastal |

| 43 | Burundi | Low income | Inland |

| 44 | Lesotho | Low-middle income | Inland |

| 45 | Djibouti | Low-middle income | Coastal |

| 46 | Cape Verde | Low-middle income | Island |

| 47 | Central African Republic | Low income | Inland |

| 48 | Gambia | Low income | Coastal |

| 49 | Seychelles | High income | Island |

| 50 | Sao Tome and Principe | Low-middle income | Island |

Table A2.

Proportion of embodied labor in final demand in China, 2000~2015 (unit: thousands of people).

Table A2.

Proportion of embodied labor in final demand in China, 2000~2015 (unit: thousands of people).

| Year | Labor Embodied in Final Demand | Labor Embodied in Final Consumption | Final Consumption (Household) | Final Consumption (Non-Profit Institutions) | Final Consumption (Government) | Others (Gross Fixed Capital Formation etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 559,202 | 358,533 | 263,740 | 7397 | 87,396 | 200,670 |

| 2001 | 573,612 | 364,743 | 263,805 | 7420 | 93,518 | 208,869 |

| 2002 | 577,723 | 366,524 | 264,020 | 7453 | 95,051 | 211,199 |

| 2003 | 572,515 | 355,534 | 253,446 | 7257 | 94,830 | 216,981 |

| 2004 | 562,776 | 343,602 | 245,667 | 7162 | 90,773 | 219,174 |

| 2005 | 562,098 | 341,754 | 243,796 | 7157 | 90,801 | 220,345 |

| 2006 | 557,888 | 338,659 | 241,174 | 7204 | 90,281 | 219,229 |

| 2007 | 569,497 | 335,771 | 241,720 | 7328 | 86,722 | 233,726 |

| 2008 | 584,142 | 342,282 | 245,404 | 7487 | 89,391 | 241,860 |

| 2009 | 634,359 | 369,468 | 262,849 | 7921 | 98,698 | 264,891 |

| 2010 | 631,978 | 363,213 | 258,765 | 8071 | 96,377 | 268,765 |

| 2011 | 638,812 | 362,705 | 260,197 | 8327 | 94,182 | 276,106 |

| 2012 | 647,663 | 370,710 | 266,912 | 8584 | 95,214 | 276,952 |

| 2013 | 660,252 | 378,961 | 267,334 | 8634 | 102,993 | 281,290 |

| 2014 | 663,361 | 375,028 | 265,884 | 8683 | 100,462 | 288,333 |

| 2015 | 666,767 | 363,596 | 260,139 | 8557 | 94,910 | 303,171 |

Table A3.

Proportion of embodied labor in final demand in Africa, 2000~2015 (unit: thousands of people).

Table A3.

Proportion of embodied labor in final demand in Africa, 2000~2015 (unit: thousands of people).

| Year | Labor Embodied in Final Demand | Labor Embodied in Final Consumption | Final Consumption (Household) | Final Consumption (Non-Profit Institutions) | Final Consumption (Government) | Others (Gross Fixed Capital Formation etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 212,889 | 176,166 | 133,717 | 13,013 | 29,434 | 36,723 |

| 2001 | 220,423 | 181,691 | 137,261 | 13,837 | 30,593 | 38,732 |

| 2002 | 226,810 | 186,747 | 140,877 | 14,306 | 31,564 | 40,063 |

| 2003 | 233,933 | 192,477 | 144,893 | 14,962 | 32,622 | 41,456 |

| 2004 | 240,191 | 197,084 | 148,652 | 15,168 | 33,263 | 43,107 |

| 2005 | 248,032 | 203,434 | 153,429 | 15,783 | 34,222 | 44,598 |

| 2006 | 255,949 | 208,903 | 157,671 | 16,372 | 34,861 | 47,046 |

| 2007 | 265,195 | 216,355 | 163,264 | 17,041 | 36,050 | 48,840 |

| 2008 | 283,701 | 230,431 | 173,766 | 17,385 | 39,280 | 53,270 |

| 2009 | 295,197 | 239,965 | 180,061 | 17,857 | 42,047 | 55,233 |

| 2010 | 300,193 | 243,439 | 182,525 | 18,313 | 42,601 | 56,754 |

| 2011 | 303,467 | 245,822 | 184,418 | 18,860 | 42,544 | 57,645 |

| 2012 | 315,005 | 254,023 | 190,114 | 19,630 | 44,278 | 60,983 |

| 2013 | 326,152 | 263,908 | 196,450 | 20,596 | 46,862 | 62,244 |

| 2014 | 334,018 | 267,871 | 199,669 | 20,846 | 47,356 | 66,147 |

| 2015 | 343,810 | 276,289 | 206,415 | 21,514 | 48,361 | 67,521 |

Table A4.

Embodied labor transfer between China and Africa, 2000~2015 (unit: millions of people).

Table A4.

Embodied labor transfer between China and Africa, 2000~2015 (unit: millions of people).

| Labor Flow from China to Africa | Agriculture | Industry | Service | Labor Flow from Africa to China | Agriculture | Industry | Service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2000 | 580 | 716 | 380 | 2000 | 2669 | 210 | 198 |

| 2001 | 547 | 694 | 389 | 2001 | 2777 | 226 | 219 |

| 2002 | 539 | 703 | 419 | 2002 | 3103 | 248 | 241 |

| 2003 | 606 | 859 | 513 | 2003 | 3134 | 297 | 285 |

| 2004 | 682 | 982 | 627 | 2004 | 3472 | 351 | 342 |

| 2005 | 706 | 1070 | 749 | 2005 | 3789 | 394 | 399 |

| 2006 | 766 | 1230 | 914 | 2006 | 4323 | 462 | 483 |

| 2007 | 785 | 1349 | 1109 | 2007 | 5081 | 578 | 586 |

| 2008 | 740 | 1344 | 1144 | 2008 | 5321 | 573 | 557 |

| 2009 | 580 | 1132 | 982 | 2009 | 5924 | 616 | 539 |

| 2010 | 593 | 1226 | 1117 | 2010 | 7327 | 798 | 750 |

| 2011 | 587 | 1295 | 1248 | 2011 | 7775 | 958 | 928 |

| 2012 | 550 | 1288 | 1284 | 2012 | 8015 | 991 | 949 |

| 2013 | 501 | 1215 | 1266 | 2013 | 8373 | 1035 | 1010 |

| 2014 | 450 | 1175 | 1307 | 2014 | 8761 | 1139 | 1149 |

| 2015 | 384 | 1077 | 1312 | 2015 | 8792 | 1177 | 1257 |

Appendix B. The Structure of the Multi-Regional Input-Output Model (MRIO)

Multiregional Input-Output (MRIO) analysis reflects the relationship between intermediate input and final demand among all regions and sectors within the global supply chain, thus providing a more detailed sectoral trade relationship around the world. According to the value-based input-output model, the global MRIO could be shown as below:

Table A5.

The global MRIO.

Table A5.

The global MRIO.

| Intermediate Input | Final Demand | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Region 1 | … | Region M | Region 1 | … | Region M | Total Output | |||||||

| Sector 1 | … | Sector N | … | Sector 1 | … | Sector N | Different Consumption Categories | … | Different Consumption Categories | ||||

| Intermediate Input | Region 1 | Sector 1 | … | … | … | … | |||||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | ||

| Sector N | … | ||||||||||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | ||

| Region M | Sector 1 | … | … | ||||||||||

| … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | … | ||

| Sector N | … | … | … | ||||||||||

| Initial Input | … | … | … | ||||||||||

| Total Input | … | … | … | ||||||||||

Supposed a world with regions, each with sectors, where represents the intermediate input from sector of region to sector of region 1, and represents the final demand of sector in region from region 1. represents the initial input of sector in region , and represents the total output of sector in region .

Based on the MRIO balance, we can obtain the following equation:

We then definite the input-output coefficient to describe the consumption in other sectors when sector produces one unit output. Accordingly, (A1) could be rewritten as:

(A2) could be expressed in matrix form as:

where reflects the direct consumption relationship between regions, and is the classic Leontief Inverse Matrix, as shown below:

Therefore, we can finally derive the total output of region :

The total output of region r is divided into parts that respectively come from the final demand of regions . For region and region , is the added value of region driven by the final consumption of region .

References

- Adolph, Christopher, Vanessa Quince, and Aseem Prakash. 2016. The Shanghai Effect: Do Exports to China Affect Labor Practices in Africa? World Development 89: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamawi, Ali, Joy Murray, and Manfred Lenzen. 2014. The Employment Footprints of Nations. Journal of Industrial Ecology 18: 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsamawi, Ali, Joy Murray, Manfred Lenzen, and Rachel C. Reyes. 2017. Trade in occupational safety and health: Tracing the embodied human and economic harm in labour along the global supply chain. Journal of Cleaner Production 147: 187–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artuc, Erhan, Daniel Lederman, and Guido Porto. 2015. A mapping of labor mobility costs in the developing world. Journal of International Economics 95: 28–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auer, Raphael, and Andreas M. Fischer. 2010. The effect of low-wage import competition on U.S. inflationary pressure. Journal of Monetary Economics 57: 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Autor, David H., David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson. 2013. The China Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition in the United States. American Economic Review 103: 2121–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsvik, Ragnhild, Sissel Jensen, and Kjell G. Salvanes. 2015. Made in China, sold in Norway: Local labor market effects of an import shock. Journal of Public Economics 127: 137–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Andrew B., J. Bradford Jensen, and Peter K. Schott. 2006. Survival of the best fit: Exposure to low-wage countries and the (uneven) growth of U.S. manufacturing plants. Journal of International Economics 68: 219–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camaratta, Rubens, Tiago Moreno Volkmer, and Alice Gonçalves Osorio. 2020. Embodied energy in beverage packaging. Journal of Environmental Management 260: 110172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cepeda-López, Freddy, Fredy Gamboa-Estrada, Carlos León, and Hernán Rincón-Castro. 2019. The evolution of world trade from 1995 to 2014: A network approach. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 28: 452–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Roberto, Linda Kaltani, and Norman V. Loayza. 2009. Openness can be good for growth: The role of policy complementarities. Journal of Development Economics 90: 33–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Zhan-Ming, and Guo-Qian Chen. 2011. An overview of energy consumption of the globalized world economy. Energy Policy 39: 5920–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, Francisco, Jason Garred, and Joao Paulo Pessoa. 2016. Winners and losers from a commodities-for-manufactures trade boom. Journal of International Economics 102: 50–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costanza, Robert. 1980. Embodied energy and economic valuation. Science 210: 1219–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, Steven J., and Ken Caldeira. 2010. Consumption-based accounting of CO2 emissions. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 107: 5687–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Sebastian. 1998. Openness, Productivity and Growth: What Do We Really Know? Economic Journal 108: 383–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenman, Joshua. 2012. China-Africa Trade Patterns: Causes and consequences. Journal of Contemporary China 21: 793–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, Syeda Tamkeen, and Abdul Qayyum Khan. 2019. Globalization and female labor force participation: The role of trading partners. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 28: 365–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feenstra, Robert C. 2015. Advanced International Trade: Theory and Evidence Second Edition. Economics Books 66: 541–44. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher, Eric O’N. 2011. Introduction to Heckscher–Ohlin theory: A modern approach. International Review of Economics & Finance 20: 129–30. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Pinelopi Koujianou, and Nina Pavcnik. 2007. Distributional Effects of Globalization in Developing Countries. Journal of Economic Literature 45: 39–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Paredes, Jorge, Eiji Yamasue, Hideyuki Okumura, and Keiichi N. Ishihara. 2015. The Labour Footprint: A Framework to Assess Labour in a Complex Economy. Economic Systems Research 27: 415–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Mengyao, and Guoqian Chen. 2018. Global arable land transfers embodied in Mainland China’s foreign trade. Land Use Policy 70: 521–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Mengyao, Guoqian Chen, M. T. Mustafa, Tasawar Hayat, Ling Shao, Jiashuo Li, Xiaohua Xia, and Xi Ji. 2015. Embodied Water for Urban Economy: A Three-Scale Input–Output Analysis for Beijing 2010. Ecological Modelling 318: 19–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardadi, Gilang, and Massimo Pizzol. 2017. Extending the Multiregional Input-Output Framework to Labor-Related Impacts: A Proof of Concept. Journal of Industrial Ecology 21: 1536–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Rui, Manfred Lenzen, and Arunima Malik. 2019. CO2 emissions embodied in China’s export. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 28: 919–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xi, Mengyao Han, and Sergio Ulgiati. 2020a. Optimal allocation of direct and embodied arable land associated to urban economy: Understanding the options deriving from economic globalization. Land Use Policy 91: 104392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xi, Pinyi Su, Yifang Liu, Guowei Wu, and Xudong Wu. 2023. Mutual Complementarity of Arable Land Use in the Sino-Africa Trade: Evidence from the Global Supply Chain. Land Use Policy 128: 106588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xi, Yifang Liu, Guowei Wu, Pinyi Su, Zhen Ye, and Kuishuang Feng. 2022. Global Value Chain Participation and Trade-Induced Energy Inequality. Energy Economics 112: 106175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xi, Yifang Liu, Jing Meng, and Xudong Wu. 2020b. Global Supply Chain of Biomass Use and the Shift of Environmental Welfare from Primary Exploiters to Final Consumers. Applied Energy 276: 115484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Xi, Yifang Liu, Mengyao Han, and Jing Meng. 2020c. The Mutual Benefits from Sino-Africa Trade: Evidence on Emission Transfer Along the Global Supply Chain. Journal of Environmental Management 263: 110332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, Xiao. 2015. Employment effects of trade in intermediate and final goods: An empirical assessment. International Labour Review 154: 147–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplinsky, Raphael, and Mike Morris. 2008. Do the Asian Drivers Undermine Export-oriented Industrialization in SSA? World Development 36: 254–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimis, Charalambos. 2008. Survival and expansion: Migrants in Greek rural regions. Population, Space and Place 14: 511–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konings, Piet. 2007. China and Africa: Building a Strategic Partnership. Journal of Developing Societies 23: 341–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, Ruyin, Jinqiu Li, Hong Chen, Linling Zhang, and Qianwen Li. 2018. Embodied carbon dioxide flow in international trade: A comparative analysis based on China and Japan. Journal of Environmental Management 209: 371–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsumoto, Ken’ichi. 2019. Climate change impacts on socioeconomic activities through labor productivity changes considering interactions between socioeconomic and climate systems. Journal of Cleaner Production 216: 528–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peh, Kelvin S.-H., and Jonathan Eyal. 2010. Unveiling China’s impact on African environment. Energy Policy 38: 4729–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, Glen P., and Edgar G. Hertwich. 2006. Pollution embodied in trade: The Norwegian case. Global Environmental Change 16: 379–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocco, Matteo V., and Emanuela Colombo. 2016. Internalization of human labor in embodied energy analysis: Definition and application of a novel approach based on Environmentally extended Input-Output analysis. Applied Energy 182: 590–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogaly, Ben. 2008. Intensification of workplace regimes in British horticulture: The role of migrant workers. Population, Space and Place 14: 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, J. Ruffin. 1967. A note on the Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. Journal of International Economics 7: 403–5. [Google Scholar]

- Rye, Johan Fredrik. 2018. Labour migrants and rural change: The “mobility transformation” of Hitra/Frøya, Norway, 2005–2015. Journal of Rural Studies 64: 189–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakai, Marco, Anne Owen, and John Barrett. 2017. The UK’s Emissions and Employment Footprints: Exploring the Trade-Offs. Sustainability 9: 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakyi, Daniel, Jose Villaverde, and Adolfo Maza. 2014. Trade openness, income levels, and economic growth: The case of developing countries, 1970–2009. The Journal of International Trade & Economic Development 24: 860–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, Moana S., Laura Golsteijn, Mark A. J. Huijbregts, Richard Wood, and Edgar G. Hertwich. 2014. The “Bad Labor” Footprint: Quantifying the Social Impacts of Globalization. Sustainability 6: 7514–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simas, Moana, Richard Wood, and Edgar Hertwich. 2015. Labor Embodied in Trade: The role of labor and energy productivity and implications for greenhouse gas emissions. Journal of Industrial Ecology 19: 343–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Bin, B. W. Ang, and Melissa Low. 2013. Input–output analysis of CO2 emissions embodied in trade and the driving forces: Processing and normal exports. Ecological Economics 88: 119–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Xudong, Jinlan Guo, Chaohui Li, Guo Qian Chen, and Xi Ji. 2020. Carbon Emissions Embodied in the Global Supply Chain: Intermediate and Final Trade Imbalances. Science of The Total Environment 707: 134670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Würtenberger, Laura, Thomas Koellner, and Claudia R. Binder. 2006. Virtual land use and agricultural trade: Estimating environmental and socio-economic impacts. Ecological Economics 57: 679–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Xiang, David Daokui Li, and Mofei Zhao. 2018. “Made in China” matters: Integration of the global labor market and the global labor share decline. China Economic Review 52: 16–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).