Another essential phenomenon that has been extensively examined in the literature is that of horizontal and vertical segregation, whereby women are overrepresented in precarious, low-skilled, part-time, and atypical jobs and face a greater risk of economic insecurity (

Jacobs 1989;

Levanon and Grusky 2016;

Torre and Jacobs 2021). Horizontal segregation occurs when women are under (or over) represented in specific occupations or sectors; this tendency is strictly correlated with the expansion of the service economy (

Blackburn et al. 2002;

Torre 2019). On the other hand, vertical segregation denotes a hierarchical divide (

Albrecht et al. 2003;

Baxter and Wright 2000;

Christofides et al. 2013), with women being penalized at the higher level (in terms of income, prestige, and part-time versus full-time employment). In short, women’s career and earning opportunities are more limited than those of men, and the overrepresentation of women in part-time and temporary jobs has clear gender-related outcomes. This fact has significant consequences on the gender wage gap, which, measured in terms of average earnings, shows that women earn about 80% of what men do, even when they hold the same jobs (

Levanon et al. 2009;

Levanon and Grusky 2016;

Ngai and Petrongolo 2017).

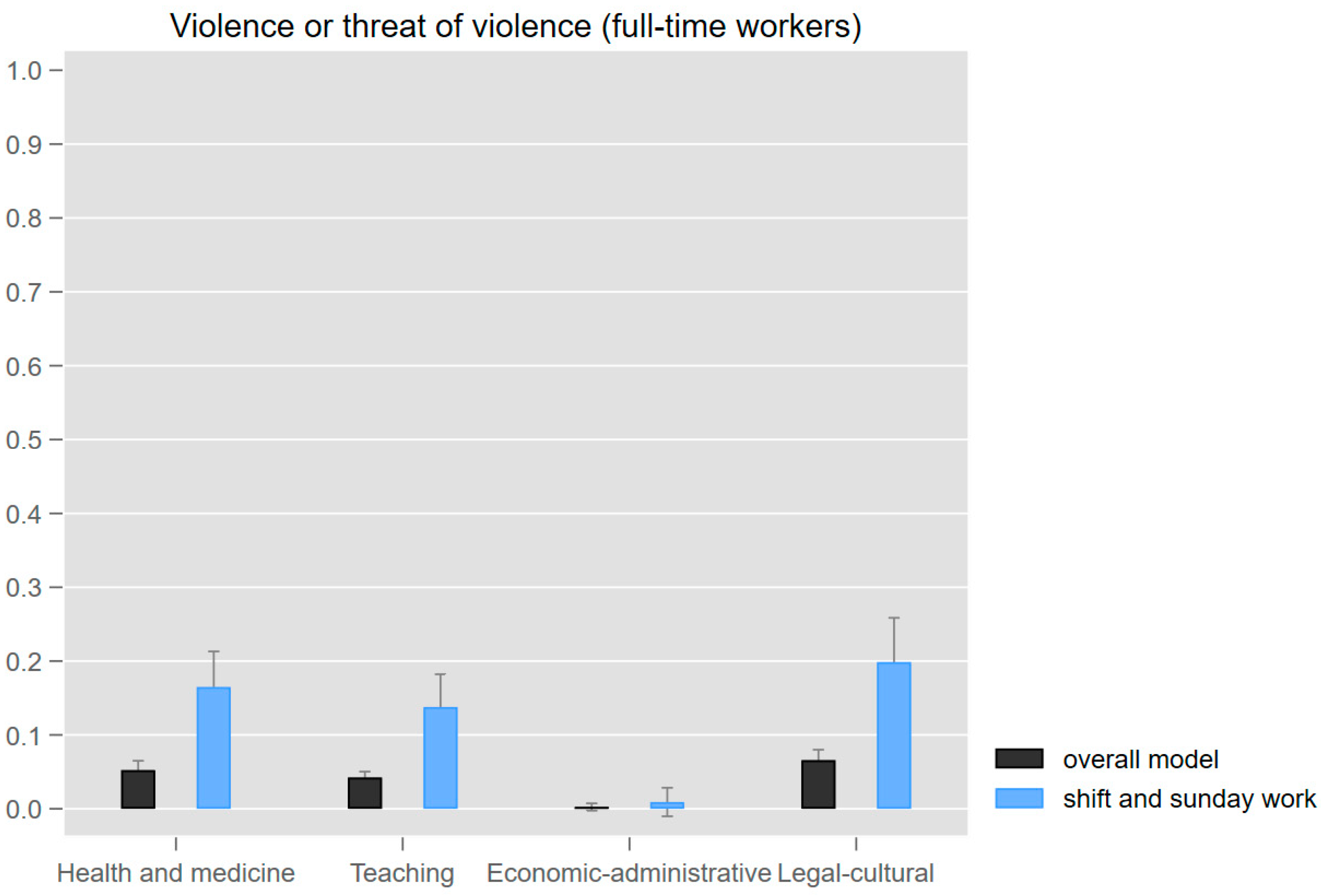

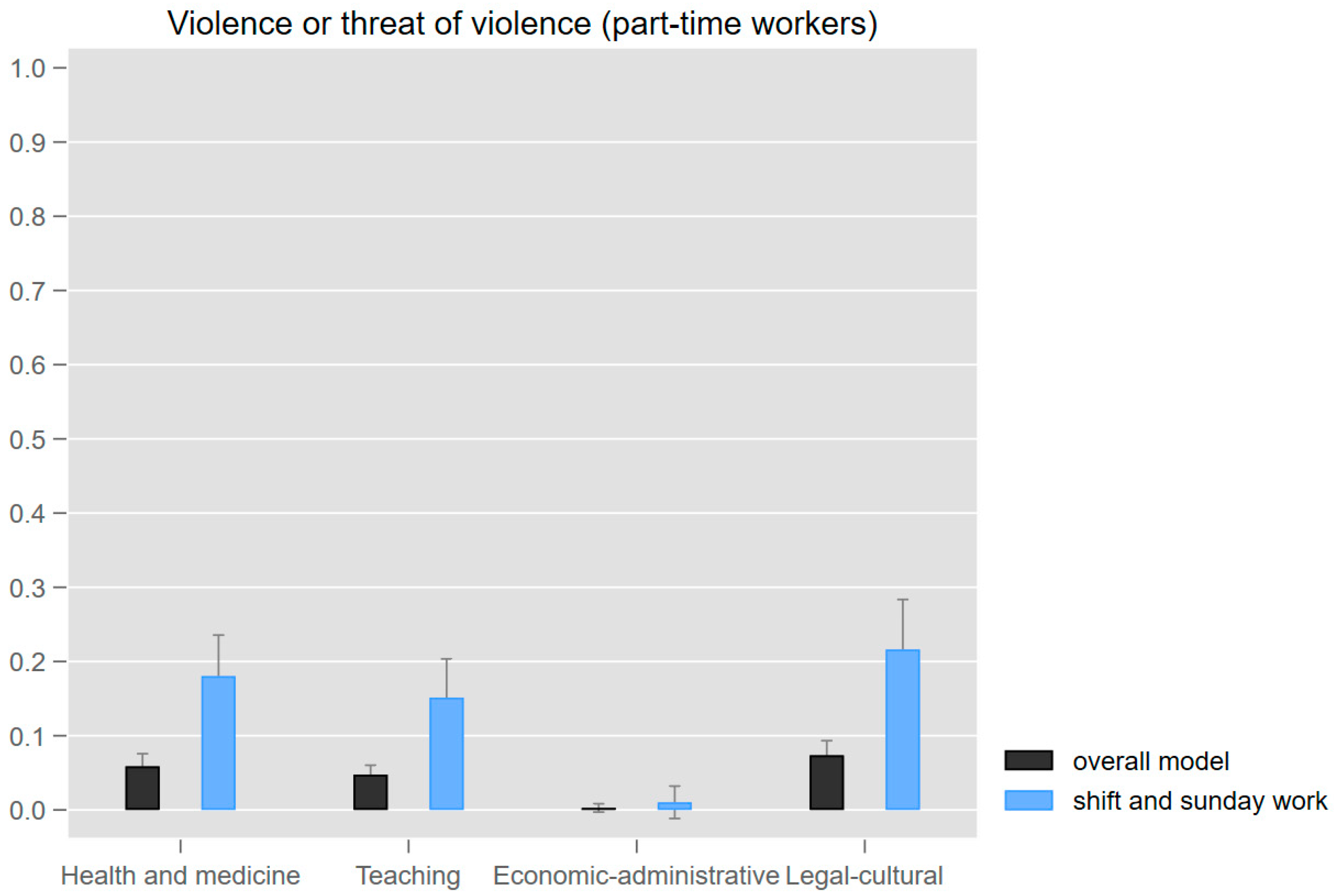

Little research has been conducted beyond the study of inequality in material resources. There has been limited analysis of the possible link between women’s employment growth and segregation and more immaterial aspects such as work strains, gender-based violence, and sexual harassment. Nevertheless, gender-based violence in the workplace represents a severe violation of human rights and an attack on women’s dignity and physical and psychological integrity. Across the world, 35 percent of women fall victim to direct violence in the workplace; of these, between 40 and 50 percent are subjected to unwanted sexual advances, physical contact, or other forms of sexual harassment (

European Economic and Social Committee 2015). Gender-based violence comes at a cost to employers as well, whether it takes place in the workplace, in public places, or in the home. According to the United Nations, such violence can impact the workplace in the form of decreased productivity, increased absenteeism, health and safety risks, and increased healthcare costs for the employer. These studies provide precious insights into the social conditions underlying the growth in female employment and reveal the twofold effect of expanding women’s employment opportunities.

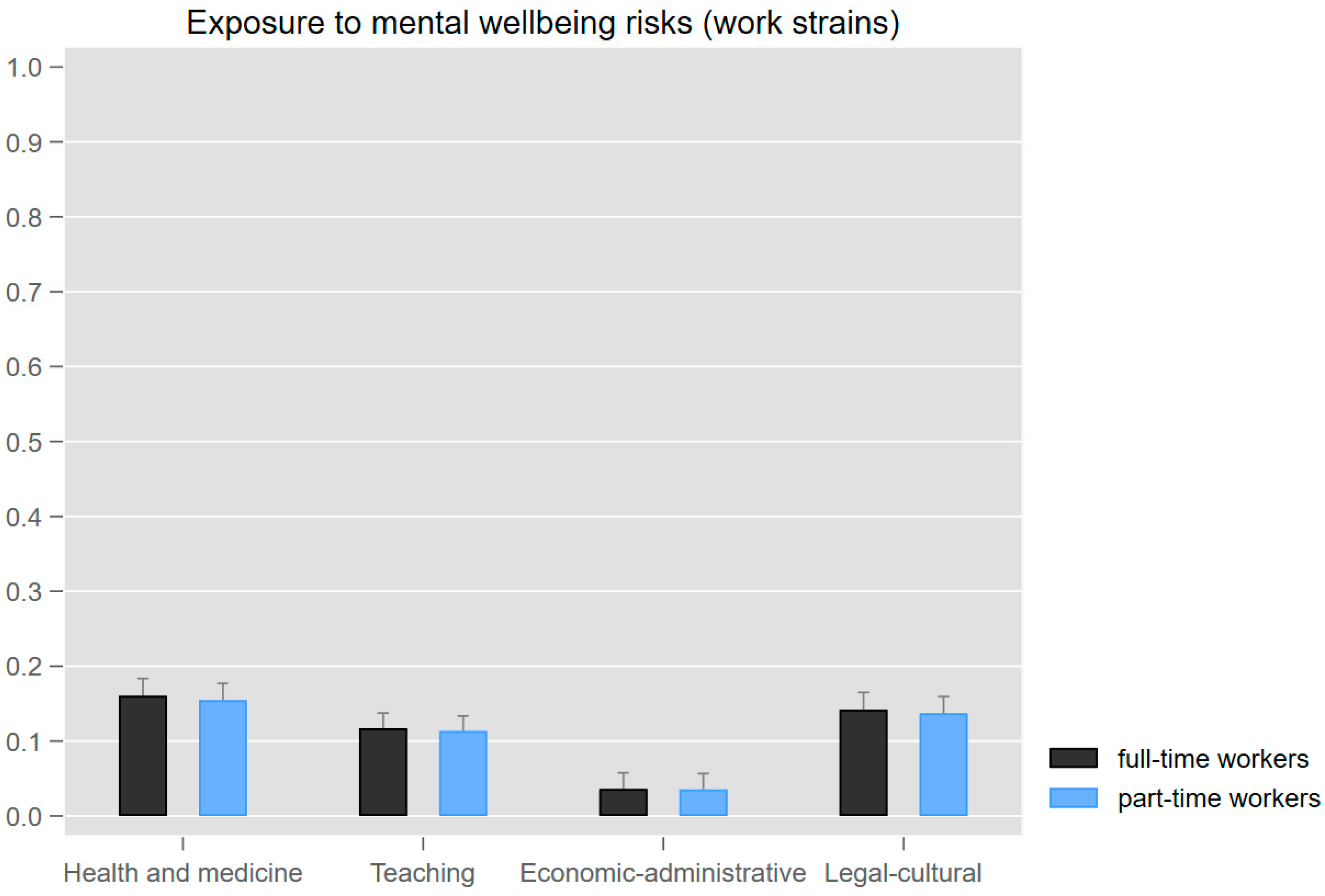

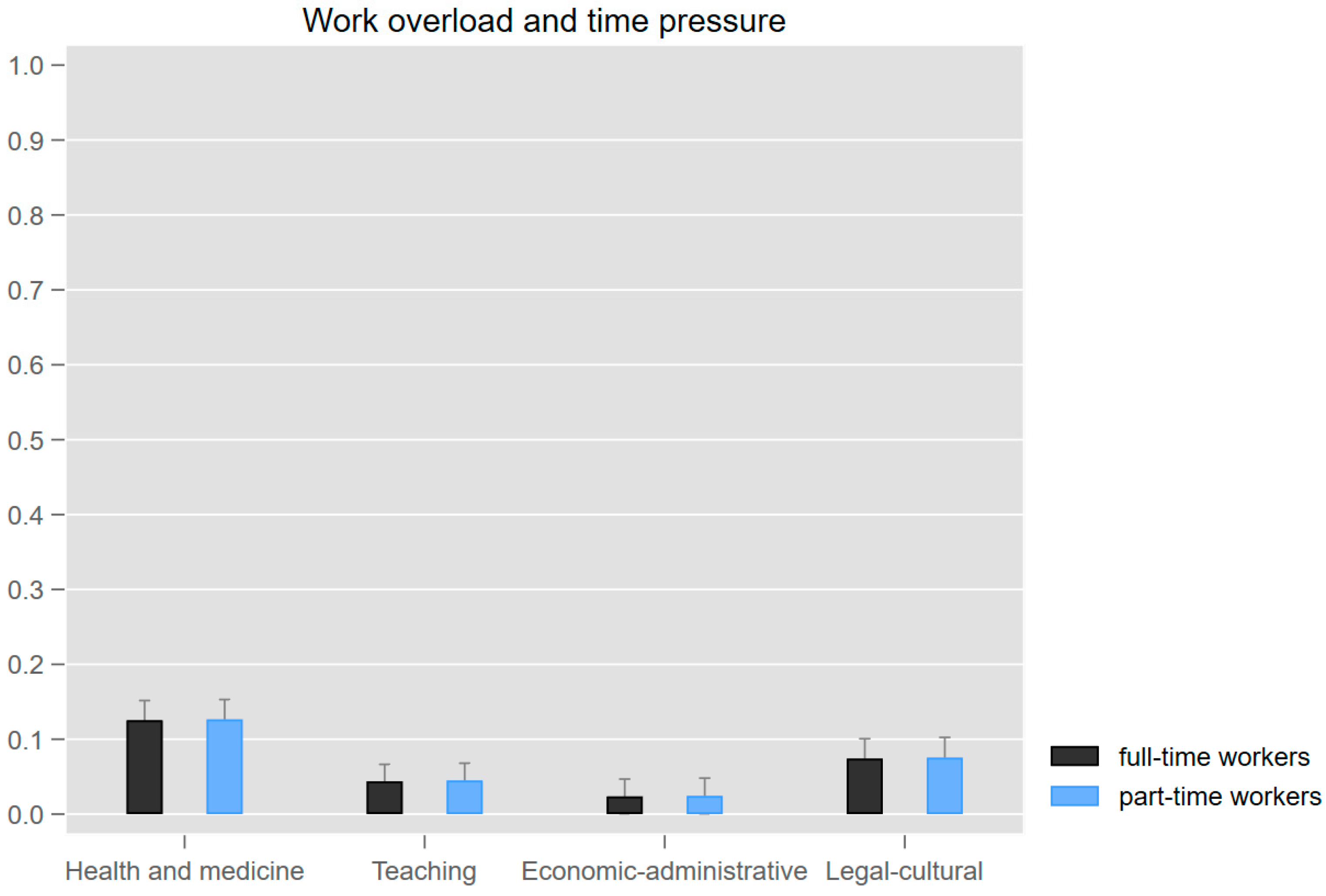

This paper focuses on a specific category of women at work and investigates differences in work-related strains among those women working as professionals. More precisely, it focuses on professionals employed in the following specific areas: STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics), healthcare and medicine, teaching and education, economic and administrative occupations, and legal and cultural occupations. The reason for selecting these categories is that they account for the highest percentage of employees reporting that their mental well-being is at risk. Secondly, these categories reveals a vast spectrum of occupations in terms of tasks and practices.

Our analysis focuses on the quality of working conditions among those women professionals employed in specific occupational groupings. Our research critically questions the compensating differential theory that assumes that female-dominated occupations have more “women-friendly” working arrangements that offset lower salaries. The data available show, on the contrary, that interactive service jobs are more exposed to risks to the mental well-being of female workers. Moreover, empirical evidence shows the relevance of “within-gender” inequalities, as professional women working in different occupations face a variety of strains deriving from their jobs.

Our analysis contributes to the literature in several ways. It illustrates how female labor market segregation may be linked to work strains, exposure to violent behavior, and the risks to workers’ mental well-being. On the other hand, it develops an approach that is not mainly interested in the customary between-gender inequalities, but that empirically reveals “within-gender” differences between women in positions of workplace authority. Our analysis also offers policy recommendations for improving female workers’ health conditions in certain occupations where control is not only exercised by employers or managers, but also by customers and where emotional labor represents an important aspect of a worker’s tasks.

1.1. The Gender Penalty: Between Compensating Differentials and Devaluation

The structure of the economy is crucial for understanding the determinants of women’s disadvantaged position in the labor market. In a nutshell, the expansion of the service sector stimulates the growth of so-called “pink-collar jobs” since they attract women much more than they do men. These jobs are often located in the secondary segments of the labor market, and they entail more unstable careers and lower wages, to the extent that some scholars call them “occupational ghettos” (

Levanon and Grusky 2016).

This phenomenon is influenced by several factors that have been highlighted in the literature on women’s occupational segregation. Firstly, it reveals that some of the activities performed by women are “functionally and symbolically” similar to the traditional unpaid domestic activities performed by women (

Charles and Grusky 2004;

Levanon and Grusky 2016). As this effect is present to a greater extent in non-manual occupations, it is a source of horizontal segregation and reinforces the concentration of women in certain specific professions (

England et al. 2007). Secondly, the growth of the service sector has increased employment demand to the point where it exceeds the supply of non-married women. This makes employers hire previously inactive women (

Charles and Grusky 2004;

Levanon et al. 2009;

Ngai and Petrongolo 2017) and promotes the growth of a new workforce with more pressing domestic responsibilities and a propensity to seek flexible forms of employment, such as part-time working (

Reskin and Roos 1990). As a result, the service sector becomes a reservoir of female employment “by default” (

Charles 2005;

Charles and Grusky 2004;

Iversen and Rosenbluth 2013;

Ngai and Petrongolo 2017). Thirdly, the advent of a post-industrial society has led to a further differentiation in the division of labor, with the corresponding growth in functional specialization and the routinization of working tasks and HR practices (

Charles and Grusky 2004;

Ngai and Petrongolo 2017). One effect of this has been the replacement of small, specialized stores with supermarkets and large retail chains. As small-scale businesses decline, sales and clerical occupations in these sectors are routinized and subjected to a deskilling process; moreover, many women have been hired to fill these new positions. At the same time, however, women’s job opportunities in management have increased, as this process requires a greater ability to supervise and coordinate deskilled jobs (

Charles and Grusky 2004;

Mandel 2012). The clustering of men and women in these occupations may account for up to 40% of the gender wage gap (

Barcus 2022;

Fuller and Hirsh 2019).

Starting from this premise, an increasing line of research goes beyond the study of inequality in material resources, such as wages, to investigate how segregation may be linked to work strains and gender-based violence, especially sexual harassment (

Folke and Rickne 2022;

Stojmenovska 2023). Work strains, psychosocial risks, and the risks to workers’ mental well-being have become a highly pressing issue. A recent report by the European Agency for Safety and Health (EU-OSHA) found that “exposure to psychosocial risks is increasing, with mental health prevalence still emerging. Major work-related exposures have grown in the past 15 to 25 years that is, time pressure, difficult clients, longer working hours and poor communication. There is also some evidence that countries with over average employment in sectors like health and care or other human and client-oriented services (education, social work, tourism, entertainment) suffer from longer working hours and more mental burden. The northern countries are at the top of the countries with highest mental burden. The southern countries have a high share of specific psychosocial risks related to work in tourism and entertainment, characterized by atypical working times and issues with difficult clients.” (

EU-OSHA 2023, p. 59). Exposure to such strains has become an important aspect of inequality in the labor market.

Within the literature, evidence has emerged linking gender segregation to gender-based violence. Specifically, women are reported to be more exposed to sexual harassment and gender-based violence in high-paid, male-dominated occupations. At the same time, men experience greater exposure to sexual harassment in female-dominated, low-paid occupations (

Folke and Rickne 2022).

Stojmenovska (

2023) investigated the impact of managerial occupations on women’s well-being; in doing so, she found a greater incidence of burnout and other work strains among men. She argues that exposure to work strains and related health problems should be considered to represent a significant dimension of gender inequality.

These studies provide very valuable insights into the social conditions of women’s employment growth, showing the twofold effect of the expansion of women’s employment opportunities in the high-skilled and low-skilled service sectors. Nevertheless, these analyses propose a trade-off logic based on the idea that segregation constitutes a two-sided process. According to this idea, female-dominated occupations should protect women better from such risks as a result of a non-monetary compensatory mechanism. Basically, the argument put forward is that lower salaries are offset by certain job benefits that facilitate work-family conciliation, making such professions more women- (or family-) friendly (

Daw and Hardie 2012;

Filer 1990;

Fuller and Hirsh 2019). This argument furthers the idea that male-dominated occupations are “culturally hostile” to women and that gender-based violence, harassment, and exposure to work strains should be seen as barriers to de-segregation. Parallel to this argument, there is also a considerable amount of research pointing to specific organizational arrangements that make male-dominated occupations less accessible to women, particularly in terms of working hours and work overload (

Battams et al. 2014;

Cha 2013). According to this research, the culture of “long working hours” is deeply embedded in male-dominated occupations, not only creating entry barriers for women but also providing reasons for leaving these occupations (

Cha 2013;

Nemoto 2013).

Compensating differentials and job amenities theories have been contested by advocates of the “devaluation theory” (

England 1992;

England et al. 2007). According to this line of research, women are paid less for the same level of skills and work experience because they work in professions in which care tasks are performed (

England 1992;

England et al. 2002;

Kilbourne et al. 1994). Various definitions have been used to frame these professions. England et al. adopted the definition of “interactive service work”, distinguishing those professions that involve care and emotional labor from those that do not. Those professions where care is provided include, for example, teaching professions, “cultural” professions, such as those of booksellers and librarians, and medical professions, comprising doctors, nurses, and dental hygienists. According to this view, the devaluation is not offset by job amenities that make these occupations “women-friendly” (

Barcus 2022;

England et al. 2002). Moreover, service work strongly impacts work strains since it modifies the typical management–employee model of labor relations. Basically, it transforms it into a customer–worker–management triangle (

Korczynski 2007;

Leidner 1993). In this setting, workers are faced with new challenges and new opportunities. On the one hand, customers have direct control over workers, who now must answer to them. In settings where the relationship is “instrumental or market-driven”, employees seem to experience greater alienation (

Gamble 2007;

Lopez 2010). However,

Lopez (

2010) argues that when customers have no more power than workers, as in the case of vulnerable people or specific categories of patients, interactions could also be fulfilling. Secondly, employment in the interactive service care sector entails emotional labor (

Hochschild 1983), which exposes workers to burnout and other forms of work strains, especially in the health and medical sector and the teaching sector (

Acheson et al. 2016;

Kwak et al. 2020;

Doyle and Hind 1998;

Kwak et al. 2020;

Noor and Zainuddin 2011;

Rickett and Morris 2021;

Yin et al. 2023). Less is known about other occupations that involve care and emotional labor, such as cultural and legal occupations, such as those of librarians, lawyers, and social workers.

1.2. Segregation and Occupations: Within-Gender Differences

The literature discussed up to now has undoubtedly helped advance our knowledge of the determinants of women’s disadvantages in the labor market. However, in studying gender inequality, research has mainly focused on two categories, namely those of women and men, and has implicitly assumed a substantial homogeneity among women. While the gender wage gap has decreased over time, in recent decades, we have observed an increase in wage inequality along other overlapping gender dividing lines. Since de-industrialization has penalized male workers more than women, scholars have focused on income inequality among men. In trying to understand the causes and consequences of the widening wage gap between skilled and unskilled (male) workers, scholars have consistently neglected inequality within the female population (

Mulè 2023). Regarding work strains, there are no significant “between-gender” differences (see

Table 1). This suggests that the “within-gender” approach is better suited for our purposes.

Quantitative research exploring issues related to gender equality is mostly interested in a multi-group comparison (

Bauer et al. 2021;

McCall 2005). This also means that disaggregating the “women category” with other variables might be a good solution for gaining new information when gender does not appear to play a crucial role as an explanatory variable.

We believe that the most fruitful way to capture inequality among women is by using the category of occupational class. Occupations are considered essential to stratification accounts for certain important reasons (

Grusky and Ku 2008;

Williams 2017). First, occupations contain the most significant elements portraying social stratification, and they determine the material and symbolic rewards related to work. The organizational position of an occupation, together with the benefits and privileges it offers, significantly conditions certain key aspects of the daily lives of those who perform the job in question. Hence, occupations provide the basis of socio-economic status and have been found to strongly predict labor market outcomes such as earnings, careers, and job quality (

Gallie 2013).

Secondly, occupations are claimed to proxy for sources of labor market stratification that often cannot be measured by means of surveys (

Williams 2017). The exact mechanisms as to how and why occupations constitute a significant source of such economic inequality range from the occupational grouping of employment relations as in the Erikson-Goldthorpe model of occupational class (

Erikson and Goldthorpe 1992) to occupations representing skill requirements (

Estévez-Abe 2011).

In this respect, several works have explored inequalities among women (

Hook and Li 2020;

Sauer and Van Kerm 2021).

Korpi et al. (

2013), for example, analyzed the impact of different social policy measures on the opportunities enjoyed by different groups of women. One of their main arguments is that social class operationalized through educational attainment should be taken into account. Other scholars (

Mulè 2023) argue that occupational class is a very useful variable for highlighting differences between subgroups of women. This resonates with our initial belief that we cannot ignore the degree to which occupations shape opportunities and distribute material and symbolic rewards. Hence, isolating female workers and disaggregating them according to occupation may prove particularly fruitful.

Indeed, when looking at occupational classes, certain important differences emerge among female workers.

Table 2 provides some insights into the matter of risk exposure. This class scheme, however, does not permit us to distinguish between occupations requiring a different amount of emotional labor. For this reason, it is preferable to work at a more disaggregated level, more specifically at the third-digit level of the ISCO-08 code. Three-digit ISCO-08 codes largely correspond to what we can define as “micro classes” (

Grusky and Sørensen 1998;

Jonsson et al. 2009;

van Leeuwen 2017). Workers who belong to the same micro class “share not only the same life chances and labor market circumstances as those in a large class, but they have something more in common, for instance, the techniques and equipment they use, the products they make, the capital they need, or the customer service skills required to serve a local community. Micro classes can be seen as occupational networks through which resources (human, cultural, social, and economic capital) are exchanged, creating layers of stratification both within and between major classes” (

van Leeuwen 2017, p. 9). At this level of disaggregation, we can therefore identify those “interactive service” occupations that require workers to perform emotional labor.

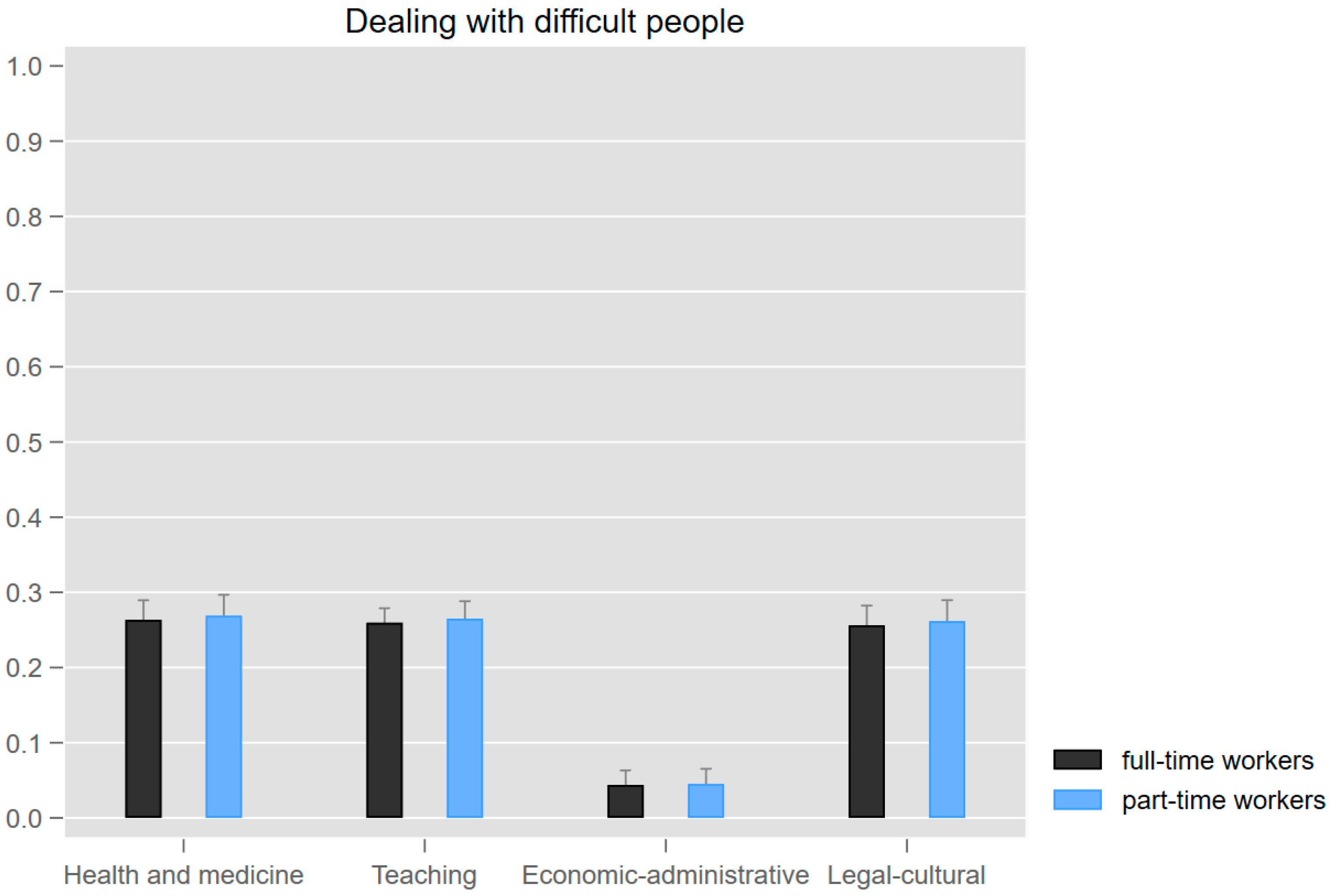

Following the “micro-class” approach, we believe that it would be more useful to study how different occupations can expose workers to work strains within the same major class. We are interested in studying work strains among professionals. This class constitutes an interesting case for two reasons. Firstly, this class contains the highest percentage of workers reporting exposure to risks to their mental well-being. Secondly, this class features a very broad spectrum of occupations in terms of the tasks and practices concerned. It essentially includes five categories of occupation: STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) occupations, health and medical professionals, teachers, economic and administrative workers, and the legal and cultural professions. These workers carry out different kinds of tasks regarding interactive service work. Service work and interactions with other people are of key importance for health professionals, teachers, and legal-cultural professionals. Moreover, these are occupations where emotional labor is a crucial part of the job.

Table 3 below shows how we grouped occupations (at the third digit level of the ISCO-08 code) from the above-mentioned categories.

We excluded architects, who are in the same ISCO sub-group as the “engineering occupations” but do not qualify as “STEM”, and we have also excluded vets from health and medical professionals since our focus is exclusively on occupations where the services provided are entirely aimed at humans.

A “within-gender”-oriented research approach is very important due to the fact that these occupations are heavily embedded in that “system of social control” constituting segregation (

Jacobs 1989). When we observe the gender composition of these occupations, we find that STEM professions are male-dominated, with women representing less than 33.3% of the workforce (

Torre 2019), while health and medicine and teaching are female-dominated (women constitute more than 66.6% of the workforce); economic and administrative occupations and the legal-cultural professions, on the other hand, are “gender-neutral”, although the second group is much closer to the female-dominated threshold (see

Table 4).

We advance two arguments. Occupations heavily shape people’s life chances. These life chances encompass both the material dimension, such as wages and compensation, and the immaterial dimension, such as how working conditions expose workers to risks to their mental health and well-being. For this reason, we further this first hypothesis.

H1. We expect to observe relevant variations within women in the exposure to work strains in different occupations.

Moreover, segregation is a system of social control (

Jacobs 1989). For this reason, compensation, pay, and working conditions should be better in occupations where women are largely excluded. Specifically, health and medicine, teaching, and legal-cultural occupations involve job tasks that require a high amount of emotional labor, which previous research hinted could be a major factor in exposing workers to strains and burnout. For this reason, we also further the following hypothesis.

H2. Work strain exposure is higher in women in health and medicine, teaching, and legal-cultural occupations.