1. Introduction

Migration has been a defining feature of human history, shaping societies and cultures for centuries. In contemporary times, it continues to play a pivotal role in reshaping the dynamics of human populations across the world, and has taken on unprecedented dimensions. In 2020, there were an estimated 281 million international migrants globally (

United Nations Population Division 2020). Migration may be internal, within a country, or international across state borders, and the term migration incorporates both voluntary decisions to move, and forced migration, though some argue this dichotomy is reductive and ‘risks undermining the potential spectrum of drivers and experiences inherent in any migration journey’ (

Erdal and Oeppen 2018;

Talleraas 2022). Three key forms of migration have been identified that encapsulate the majority of migration: labour migration, which includes the movement of both ‘high-skilled’ and ‘low-skilled’ workers, family migration for marriage or the existence of ‘transnational families’ living in different places, and humanitarian migration, which includes refugees and asylum seekers, survivors of human trafficking, unaccompanied minors and internally displaced people. Other forms of migration include lifestyle migration, where people move for a perceived increased quality of life over economic benefits, student migration, and irregular migration, defined as movement outside of the laws or regulations governing countries of origin, transit or destination (

McGarrigle 2022;

Sironi et al. 2019;

Talleraas 2022). Whatever the reason for migration, the interconnectedness of our modern world, facilitated by advancements in transportation and communication, has facilitated a complex web of global migration patterns, and the dynamics of contemporary migration are more intricate and far-reaching than ever before (

World Economic Forum 2022).

The decision to migrate, whether prompted by economic aspirations, political unrest, environmental factors, or other circumstances, initiates a complex process laden with numerous stressors that can profoundly impact the health and wellbeing of the individuals involved (

Zimmerman et al. 2011). Such stressors may occur at the pre-migration stage, for example, economic insecurity, political instability, conflict, environmental disasters and family separation; during the migration process, for example, physical hazards, violence, exploitation or legal uncertainty; and in the post-migration phase, for example, acculturation stressors such as language and cultural barriers, social isolation, discrimination and xenophobia, and economic challenges (

Byrow et al. 2022;

Li et al. 2016;

Sengoelge et al. 2022;

Zimmerman et al. 2011). Women in particular may face additional stressors such as those linked to gender-based violence, family and care responsibilities, reproductive health and rights, a lack of gender-sensitive services, and increased risk of exploitation. They may also experience a lack of empowerment, such as reduced decision-making power, particularly linked to traditional gender and family norms (

Rees and Fisher 2023;

Poya 2021;

Hawkes et al. 2021;

La Cascia et al. 2020;

Llácer et al. 2007).

In the first half of 2022, Spain saw an estimated 441,781 migrants enter the country, a 36% increase in the numbers from the second half of 2021 (

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica 2023). There are a number of routes to becoming a resident in Spain, depending on a person’s country of origin, how long they wish to stay in the country and the purpose of their time there. The process for non-EU citizens is much more complex and requires an individual to apply for one of a variety of different visa types. The applicant must first apply for temporary residency, which allows them to stay in the country for more than 90 days but less than 5 years. After this time has elapsed, permanent residency can be applied for. EU citizens have a right to remain in Spanish territory beyond 90 days, provided that they can demonstrate they are working, that they have enough resources to support themselves and not be a burden on the Spanish system, that they are a student enrolled in a course, or that they are joining an EU family member who satisfies one of the previous conditions. Whilst appointments can be solicited online, everyone applying for resident status in Spain must present a variety of documents in person to either their local ‘Oficina de Extranjeria’ (foreigners/immigration office) in Spain, or to their corresponding Spanish Consulate, depending on the visa application route (

Government of Spain 2023). In 2021, 30% of initial residency documents were granted to people from Europe, 26% to people from Africa, 33% to people from Central and South America, 2% to people from North America, and 8% to people from Asia. Over half of these documents (53%) were granted to women (

Observatorio de la Inmigracion 2023).

In addition to the stressors linked to the act of migration, the need to then interact with bureaucratic administrative processes linked to public departments in the destination country can further add to the stress and uncertainty that migrants face (

Geoffrion and Cretton 2021;

Li et al. 2016). Hattke and colleagues demonstrated, in a laboratory study setting, that people experience significant negative emotions including confusion, anger and frustration in response to bureaucratic red tape (

Hattke et al. 2019). However, this is a phenomenon also seen in the real world, which can disproportionately affect migrant groups. Referred to as ‘bureaucratic violence’ in the literature (

Heckert 2020;

Weinberg 2017), studies have shown that ‘confusing and opaque administrative processes, unpredictable wait times, costly application fees, bureaucratic errors and a lack of accountability’ to name just a few are associated with stressful life consequences for migrants (

Schmidt et al. 2023). Administrative burdens can have social, economic and psychological implications, particularly for vulnerable groups who share a larger proportion of the burden, thereby increasing existing inequalities (

Chen et al. 2017;

Chudnovsky and Peeters 2021;

Heinrich 2018).

Administrative burdens are often exacerbated by the actors involved in their management and implementation. The term ‘street-level bureaucrat’ was originally termed in the 1980s by Lipsky, to describe ‘public service workers who interact directly with citizens in the course of their jobs, and who have substantial discretion in the execution of their work’. He outlined how this is a strategy employed to handle the state–agent relationship and the increasing managerial pressure placed on street-level bureaucrats (

Lipsky 2010). Scholars in migration studies have highlighted how street-level bureaucrats interacting with migrants through social services, and in particular through immigration administration services, often use their discretion to manage or manipulate caseloads and act as gatekeepers of the borders. However, in contrast to Lipsky, they have suggested this is driven by a desire to use value judgements to determine deservingness and combat perceived fraud, rather than as a way to manage workloads (

Alpes and Spire 2013;

Ratzmann and Sahraoui 2021). In either case, the result is the creation of a power imbalance that can have adverse consequences for vulnerable groups, including increased migrant distress and impacts on mental health (

Bhatia 2020;

Schmidt et al. 2023).

Undertaking the arduous process of becoming a resident is one of the major administrative tasks that migrants must address when moving to a new country. A number of studies have documented the challenges and bureaucracy involved with undertaking administrative tasks in Spain (

European Website on Integration 2016;

Fundación Civismo 2020;

Perez et al. 2021). According to the Migrant Integration Policy Index, Spain scores higher than average, and immigrants enjoy ‘more opportunities than obstacles when it comes to integration’. The index notes a ‘slightly favourable’ score for permanent residency, with most non-EU citizens benefiting from an inclusive process. However, it also notes that access to nationality is Spain’s main area of weakness, that anti-discrimination policies, whilst in existence, are enforced by a weak equality body and that when looking at Spain’s integration policies as a whole, including labour market mobility, family reunion, education, health, political participation, permanent residence, access to nationality and anti-discrimination, Spain performs less favourably than other non-EU destination countries such as Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA (

Solano and Huddleston 2020). Certain groups of migrants, such as those seeking asylum, face additional barriers that are integrated into the public systems with the goal of keeping people out. In Spain in particular, changes to the asylum process, the digitalisation of systems and the outsourcing of administration, directly or indirectly, to private actors have been cited as specific strategies to create distance between the state and those seeking asylum, further contributing to their marginalisation and reinforcing territorial and colonial legacies (

Borelli et al. 2023).

Despite the existence of laws and frameworks to protect migrants in Spain (

European Website on Integration 2023), they still face a host of challenges and barriers to integration, including in accessing public services and interacting with public administration systems. This has been particularly documented in the healthcare field, with migrants facing reduced access to healthcare due to their immigration status, not having the correct paperwork or health card, or not being able to prove that they are eligible to receive care, such as having been in Spain for more than 90 days (

Hsia and Gil-González 2021;

Ndumbi et al. 2018;

Solanes Corella 2015). Specific challenges and barriers experienced during the residency application process in Spain, however, have not been well documented within the academic literature, particularly for migrant women. In their strategy for migration 2021–2026, the Valencian government highlighted a goal to diagnose ‘institutional racism in discriminatory actions and insurmountable bureaucratic barriers for migrants in Valencian administrations’ (

Generalitat Valenciana 2020).

This paper fills a gap in the literature by seeking to answer two main research questions: What are the specific barriers that migrant women face when applying for resident status in Spain? And do different socio-demographic subgroups of migrant women experience different barriers? These questions are answered through the use of mixed-methods data collected as part of a wider study on intimate partner violence and mental health in migrant women living in the Valencian Community of Spain. As Spain continues to attract a diverse range of international migrants, understanding the challenges and experiences specific to this group, and particularly to migrant women who face additional stressors and vulnerabilities, is of the utmost importance.

2. Materials and Methods

An online non-probabilistic cross-sectional survey was conducted of migrant women living in the Valencian Community of Spain to collect data on socio-demographic characteristics, experiences of interacting with public administration systems, symptoms of poor mental health and experiences of intimate partner violence. The survey was advertised through social media channels, including Facebook and Instagram, and was available in Spanish, English and French. Participants could opt to enter into a prize draw to win a EUR 90 voucher for El Corte Ingles once they had begun the survey. Survey instructions reminded participants that they were not required to complete the survey to be included in the prize draw. An eligibility filter was added at the beginning of the survey to increase the chance of collecting responses only from the target population. People who identified as a woman, who were aged 18 or over, were either not from Spain or were born in Spain but did not grow up in the country, and who currently resided in the Valencian Community were able to access the survey. The study was explained in full on the first page, and consent was received before proceeding. Data were collected via the LimeSurvey platform (LimeSurvey GmbH,

http://www.limesurvey.org (accessed on 14 September 2023)) between January and March 2023.

2.1. Data Collection Tool

A total of 1998 migrant women, predominantly from Europe and Latin America, accessed the survey. All respondents lived in the Valencian Community at the time of completing the survey. Forty-five percent of women completed the survey in English, 44% in Spanish and 11% in French. The survey asked women demographic and background questions including their age, ethnicity, country of origin, religion, if they had ever been married or lived with a partner, whether or not they had children, and if so, how many, and their ages.

Women were then asked about the length of time that they had lived in Spain, their current living arrangements, whether they were currently working, which included the category ‘not permitted to work’, and their approximate monthly household income. Women were also asked whether or not they were a resident in Spain. A follow-up question asked those who did have residency about any barriers that they faced during the application process, and those that did not have residency were asked what was preventing them from obtaining it. These were multiple-response questions that contained the response options ‘language barriers’, ‘lack of information’, ‘do not meet the requirements’, ‘discrimination’, ‘no barrier/not applicable’ and ‘other’. In addition to collecting quantitative data, the survey included a number of open-text comment boxes to collect more detailed qualitative information on various aspects, including barriers faced in the residency application process. In this case, the ‘other’ option contained an open-text box asking respondents to specify in more detail.

Additional sections of the survey included assessments of mental health, intimate partner violence, and ease of access to healthcare, not presented in this paper.

2.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

Two outcome variables were created to assess barriers to residency. The first was a binary ‘yes/no’ variable to identify women who had reported at least one of the barriers in the residency process. The second was a count variable, which calculated the number of barriers that each woman had reported. The maximum option was five (language barrier, lack of information, do not meet requirements, discrimination, or other).

Descriptive analyses of outcome and predictor variables were conducted to gain a comprehensive understanding of the study population. Measures of spread, such as standard deviation and interquartile ranges, were calculated to assess the dispersion and variability within each demographic attribute. Frequency distributions were plotted and histograms and box plots utilised to visualise the distributional patterns of the demographic characteristics, gain insights into central tendencies and identify potential outliers in the data.

Due to skews in the data, a number of the categorical variables were collapsed for the purposes of analysis in order to reduce the risk of complete separation. Through an iterative process, the ethnicity and country-of-origin variables were reduced down to a smaller number of categories that made logical and theoretical sense. A balance was sought between reducing the data sufficiently and retaining important distinctions between groups. The religion variable was condensed into three categories: ‘No religion/Atheist’, ‘Christian/Catholic’ and ‘Other’ based on the distribution of respondents across the different religious categories. The sexual orientation variable was condensed into a ‘majority’ (heterosexual) and a ‘minority’ (queer/gay/lesbian/bisexual) group. The age of children was categorised as either above or below 18, as it was theorised that those with adult children compared to those with minors might have experienced different challenges in the residency process. As all respondents reported that they had completed secondary education, the education variable represented ‘secondary education’ versus ‘higher education qualification’.

To assess the relationship between socio-demographic variables and the barrier-to-residency outcome variables, bivariate analyses were first conducted using Pearson’s chi-square tests for independence to test for an association between the binary variable of any barriers experienced in the residency process and socio-demographic variables, Fisher’s exact tests to test the same associations when expected cell frequencies in contingency tables were small, and Kruskal–Wallis H tests to assess associations between the number of barriers experienced and socio-demographic variables. Univariable regression analyses were performed for each socio-demographic predictor against the outcome variable. A logistic regression was used for the binary outcome variable of any barriers experienced and a Poisson regression model used for the count outcome variable of number of barriers experienced, after checking for overdispersion of the data.

Multivariable regression models were built for each barrier outcome to adjust for the confounding effects of the other socio-demographic variables. For the logistic regression model, socio-demographic predictors were added following a theoretical, hierarchical structure, in line with recommendations from

Victora et al. (

1997). The variables were categorised into theoretical levels based on whether they were directly related to the woman (age, ethnicity, country of origin, religion, education), to her close relationships (if she had ever been married or lived with a partner, whether she had children, how many and their age(s)) and to her life in Spain (the length of time in Spain, her living arrangements, whether or not she was working, her income level, and whether or not she perceived that she had social support). Variables in level 1 were added simultaneously. Those that showed significance at a level of

p < 0.05 were retained for model 2, where the level 2 variables were added. Again, those that showed statistical significance were retained. The process was repeated for the level 3 variables until a final model was reached. Age was retained as an a priori predictor in all models. The following predictors were retained in the final model: age, country of origin, sexual orientation, education, length of time in Spain, current living arrangements, working status, monthly household income and perceived social support. For the Poisson regression, the same process was conducted and the same set of predictors retained in the final model. Pearson’s chi-square test for goodness of fit was used to test the fit of the models, and odds ratios and incident-rate ratios displayed for the logistic and Poisson models, respectively. All analyses were conducted in Stata (

StataCorp LLC 2017).

2.3. Qualitative Data Analysis

If respondents selected ‘other’ in response to the barriers faced during the residency process, they were presented with an open-text comment box and asked to provide more detail. Responses to these questions were extracted from the dataset and translated into English, where necessary. A thematic analysis of the data was performed in Atlas.ti Web (

Atlas.ti Web Version 3.15.0 2022), using an iterative approach to identify codes and patterns within the data. A mixture of inductive and deductive coding was used, with a priori codes determined by the pre-existing quantitative response options, namely language barriers, a lack of information, not meeting the requirements, and discrimination. Codes were subsequently merged and grouped, allowing for larger themes within the data to emerge.

3. Results

Within the survey, 1789 women (90%) completed the demographic background questions and experiences of applying for residency. The socio-demographic distribution of respondents is summarised in

Table 1. The age of participants ranged from 18 to 85, with the average age being 37.3 (SD 13.8). The majority of participants identified as White (50.5%), followed by Latina (31.3%). Those in the ‘other’ ethnicity category included women who identified as South, East, or South East Asian, Central Asian, Middle Eastern or North African, and Black African, Black American and Black European.

Almost half of respondents came from other countries in Europe (48.2%). These were made up of respondents predominantly from Western Europe, such as the UK and France. The largest representation from Eastern Europe included Poland, Romania and the Ukraine, with a similar proportion of respondents also coming from Russia; 38.7% of respondents came from countries in Latin America, with the largest representation from Colombia and Venezuela.

The majority of respondents identified as heterosexual, had a higher education qualification and were not religious (48%); 46% were Christian or Catholic and the remaining 6% followed another religion, including Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Judaism. Just over half of respondents had ever been married or lived with a partner (56.5%); however, only 37.3% had children. Of those who had children, women had two on average, with 60% having a child under 18 and 47% having a child over 18.

Almost half of respondents (48.3%) had been living in Spain less than 3 years, indicating a significant proportion of relatively new migrants. This reflects trends in national migration data that suggest that inward migration to Spain has significantly increased since 2019 (

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica 2023). Half of the women were currently working; however, around 10% were not permitted to work due to visa restrictions. The approximate monthly household income for most women (46.1%) fell in the medium range of EUR 1000–3000. Of the respondents, 57.2% reported that they felt they had a network of social support in Spain; however, a significant proportion (42.2%) did not feel that they had support.

Two hundred and twelve respondents (11.9%) provided additional detail on barriers to residency through the open-text comment boxes. Their mean age was 37.3 (SD 11.8), reflecting that of the sample as a whole. Of them, 28% were Latina, 36% were White and 36% had a range of ‘other’ ethnicities. This representation of ‘other’ ethnicities is much larger than the general sample, suggesting that women from minoritised ethnic groups were more likely to have experienced complex or nuanced barriers in their residency application that required further detail. Of the women who left qualitative comments, 60.4% had been in Spain for less than three years.

3.1. General Barriers in the Residency Application Process

At the time of the survey, 76.5% of respondents were residents in Spain. Two thirds (64.9%) had faced at least one barrier in the residency application process, with the maximum number of barriers faced being four. The main barrier reported was a lack of information (33.7%), followed by not meeting requirements (20.5%), language barriers (19.9%) and ‘other’ barriers (17.4%). Of the respondents, 8.7% reported experiencing discrimination in the residency application process (

Table 2).

Four major themes emerged from the qualitative comments when respondents were prompted for further detail linked to ‘other’ barriers to residency: Challenges with accessing information and complex administrative processes linked to residency application, Challenges in understanding and meeting the legal requirements for residency, Interpersonal communication with public officials, and Strategies adopted by women migrants to cope with the hurdles. These have been discussed further in

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4,

Section 3.5 and

Section 3.6.

3.2. Barriers to Residency by Socio-Demographic Characteristics

Unadjusted odds ratios showed an association between all socio-demographic variables, except income level, and whether or not women had experienced a barrier in the residency process (

Table 3). After adjusting for the confounding influence of other socio-demographic predictors, women who came from Africa, Asia or the Middle East were more likely to experience barriers in the residency process than women who came from Europe (AOR 2.35, 95% CI 1.31–4.23). Those who identified as queer, lesbian, gay or bisexual were more likely to experience barriers than those who identified as heterosexual (AOR 1.78, 95% CI 1.27–2.49), as were those who had a higher education qualification compared with those who had only completed secondary education (AOR 1.83, 95% CI 1.40–2.40).

For women who had lived in Spain for more than 10 years, the odds of having experienced a barrier to residency were reduced by 61% compared with women who had been living in Spain less than one year (AOR 0.39, 95% CI 0.27–0.57). Women who lived with their parents or other family members had 2.4 times the odds (95% CI 1.31–4.24) of experiencing a barrier in the residency process compared with women who lived alone; however, no associations were seen for any other living arrangements. Finally, women who were not currently working, compared to those who were, were less likely to have experienced a barrier in the residency process (AOR 0.64, 95% CI 0.50–0.82); however those who were not permitted to work had almost twice the odds of experiencing a barrier (AOR 1.98, 95% CI 1.21–3.23).

Table 4 shows that after controlling for the effects of other socio-demographic variables, the only statistically significant association with the number of barriers faced in the residency process was for women who came from Africa, Asia or the Middle East. The expected number of barriers faced is approximately 1.23 times higher for these women, compared to women from Europe (95% CI 1.01–1.50).

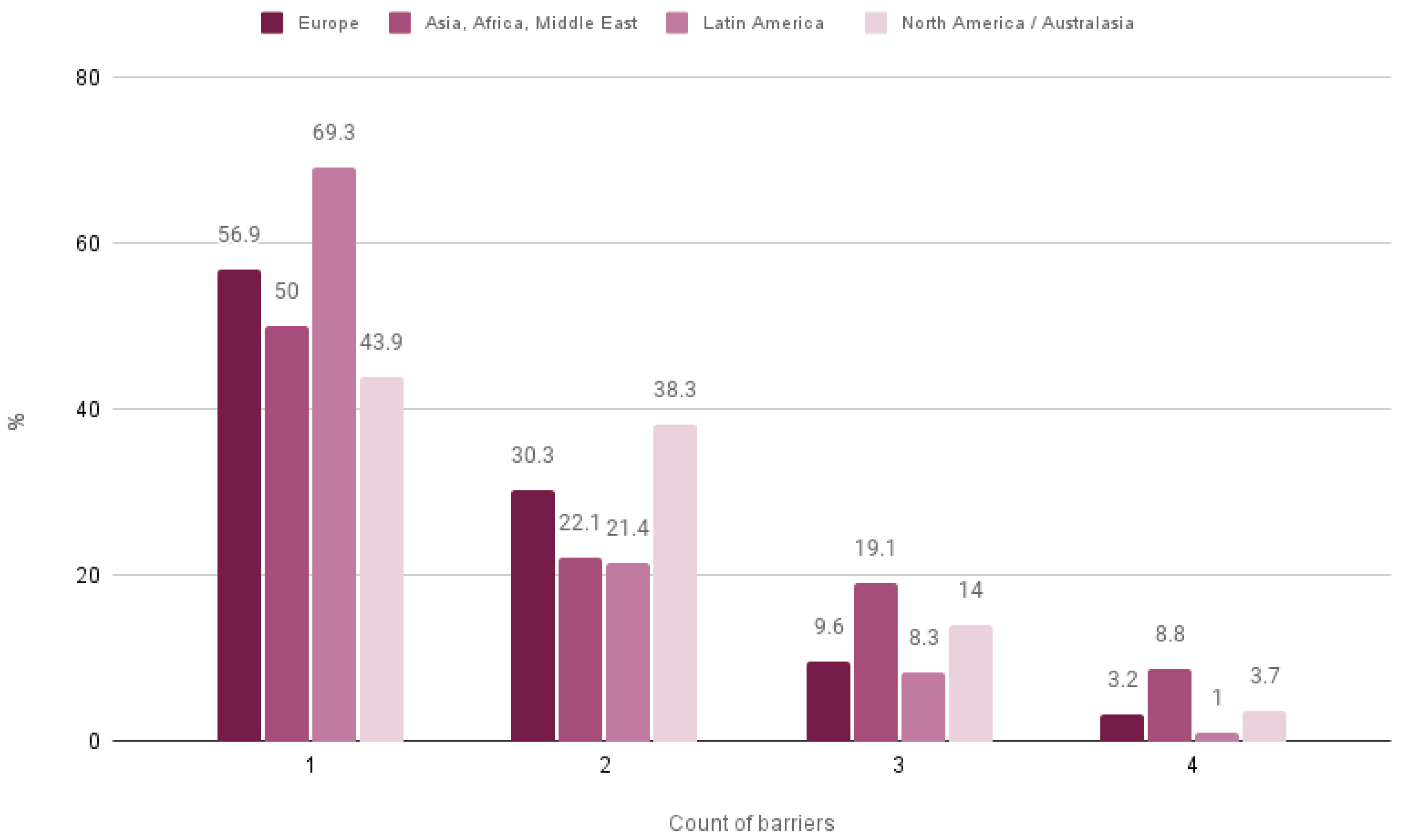

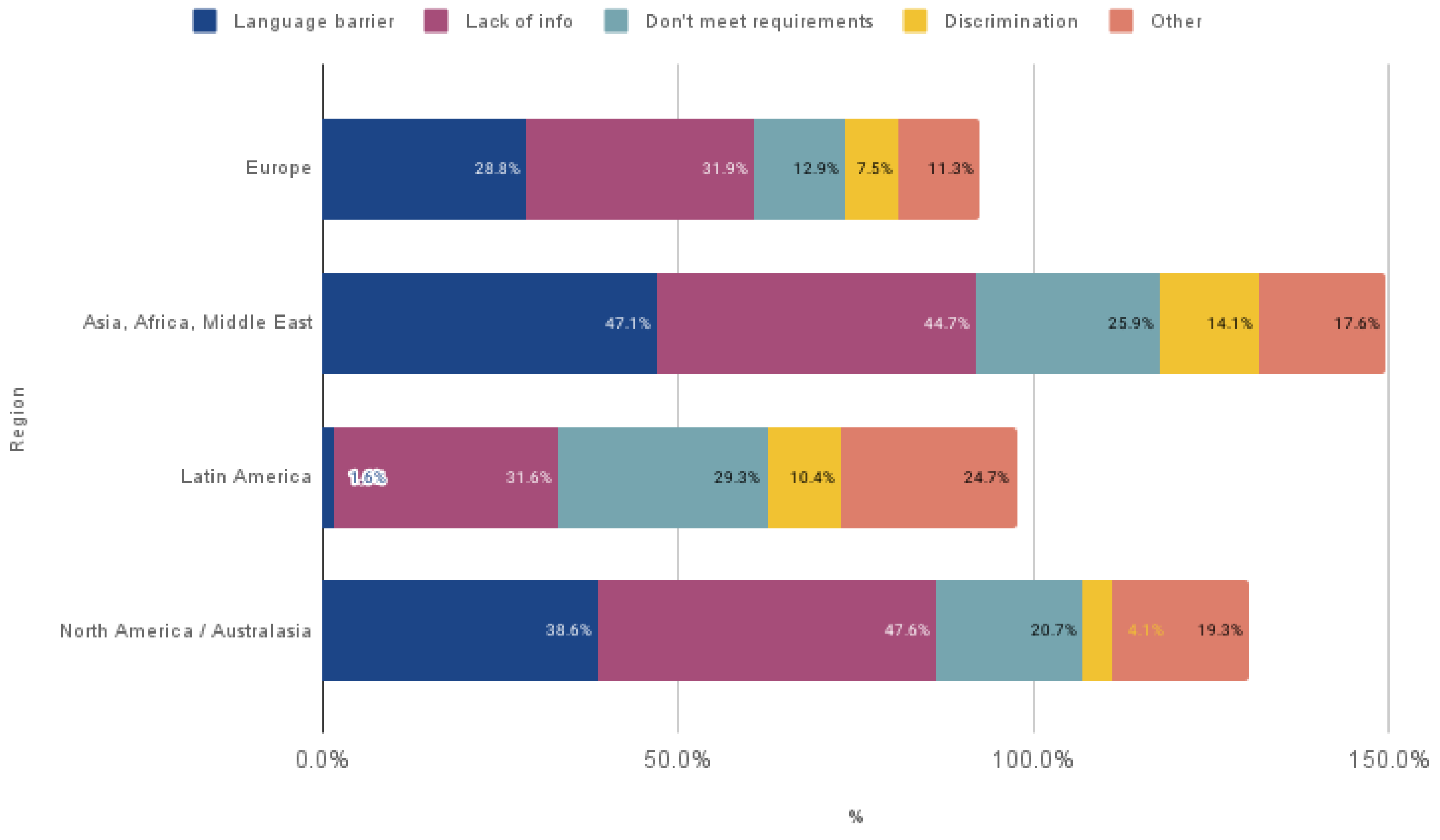

A higher proportion of women from Africa, Asia or the Middle East reported three or four barriers than women from any other region (

Figure 1). When looking at the breakdown of these barriers,

Figure 2 shows that a higher proportion of women from this region experienced language barriers (47.1%), did not meet the requirements for residency (25.9%) and experienced discrimination (14.1%), compared with women from any other region. A large proportion (44.7%) also reported a lack of information as a major barrier, similar to the proportion of women from North America/Australasia (47.6%).

Overall, these findings suggest that women from minority ethnic groups, and with minoritised sexual identities, were more likely to experience any barrier in the residency process than those from majority groups. Lower educational status, not working, and living alone appeared to be protective against barriers to residency, as did having lived in Spain a longer time. The number of barriers experienced, which could be viewed as a proxy for the severity of bureaucratic violence in the residency application process, was most pronounced for women from Africa, Asia or the Middle East, suggesting that women from these minority ethnic groups may be more vulnerable throughout the process of gaining resident status in Spain.

The following sections outline the findings from the qualitative analysis of the open-text comments, providing more detail and nuance in relation to specific challenges and barriers faced during the residency application process.

3.3. Challenges with Accessing Information and Complex Administrative Processes Linked to Residency Applications

The residency and immigration process was marred by a series of bureaucratic hurdles and difficulties, mainly stemming from complex and out-dated administrative systems, resulting in delays, inefficiencies and limited access to appointments.

Participants frequently encountered a range of administrative issues, including enduring long, complex bureaucratic processes, grappling with unclear guidelines and facing a lack of information, which ultimately led to feelings of frustration and confusion. One participant lamented that it was an ‘extremely long and tiring process that required multiple appointments and a lot of paperwork’ [27, White, UK]. Another expressed her experience with multiple barriers:

‘Paperwork, a lot of it and lack of clear and concise information and very slow’

[32, Latina, Venezuela]

Women highlighted how it was very difficult to obtain official information or advice, particularly if they were new to the country:

‘I have not been able to access advice, I have communicated with the town hall and they tell me that I must be registered for at least 1 year to be able to ask for an appointment with social work. I have been with my family to the town halls of Alicante and Benidorm and we have not obtained advice or guidance in many aspects’

[27, Latina, Colombia]

‘People assuming I knew things that make no sense for a foreigner to know (who just arrived), everything being complicated, especially anything related to the government’

[28, Latina, Puerto Rico].

This reflects the findings from the quantitative data that a major barrier in the residency application process is a lack of clear information. Participants expressed how this confusing system can lead to feelings of being overwhelmed, burnout and scepticism towards any new information provided:

‘I have gotten so much wrong and confusing information that I burn out and have difficulty believing any new information is true or will work’

[38, Black, USA].

The use of archaic and out-dated administrative processes, particularly the absence of online options for the processing of paperwork, further added to the participants’ discontent. As one participant stated,

‘No processes are online, everything must be done in person at appointments that take trial and error to get’

[25, White, New Zealand].

A major concern for applicants was the significant delays in the immigration process, which often impacted their plans and aspirations. For instance, one participant shared,

‘My paperwork was not processed in time by the embassy which led to a backlog in my documentation and my original visa expired’ [34, Latina, Paraguay]. Another remarked how ‘delays in procedures…affected my employment relationship’

[38, Latina, Colombia].

In line with stories recently published in the news (

The Local Spain 2023), securing appointments for residency applications proved to be a daunting task for many participants, as they cited corruption and opportunistic practices as additional barriers. One participant stated that it is ‘impossible to get the appointment for the application for international protection; the closed system is only managed by the mafias who sell the appointments in Valencia’ [58, Latina, Venezuela]. Another participant added, ‘There are never any appointments and when there are appointments they are in neighbouring villages, each office asks for what it wants’ [35, Latina, Uruguay]. The prevalence of intermediaries, referred to as ‘corrupt gestors’ [55, White, UK], charging exorbitant fees of ‘EUR 40–60 to help get an earlier appointment’ [32, White, Latvia], were acknowledged as the only way to be able to secure a residency appointment, which further exacerbated the situation. Consequently, applicants found themselves entangled in a web of ‘scams’ and illicit practices, hindering their access to crucial appointments.

This theme collectively highlights the complexities and bureaucratic challenges faced by individuals when dealing with the residency and immigration process. The presence of archaic systems, delays, a lack of clear information and corruption presented significant barriers, impacting applicants’ experiences and aspirations throughout the entire process.

3.4. Challenges in Understanding and Meeting the Legal Requirements for Residency

Participants encountered arduous challenges while striving to meet the stringent prerequisites of the residency process. They struggled with various obstacles that hindered their ability to fulfil specific requirements, which impeded their progress through the immigration process. The four main pathways to achieving temporary residency in Spain, that is, to have permission to stay more than 90 days but less than 5 years, for non-EU citizens include a non-lucrative visa where applicants are not permitted to work, a visa for family reunification, a visa that authorises the applicant to work in specific circumstances only, such as for people linked to scientific or academic institutions, and a visa linked to exceptional circumstances such as for international protection or for humanitarian reasons. Each route mandates a variety of pre-requisites, including being able to demonstrate sufficient economic means to support life in Spain, having adequate housing, having health insurance or being able to demonstrate that you meet the requirements for exceptional work or life circumstances (

Government of Spain 2023).

For many women, these pre-requisites presented a common barrier at the nexus of legal and financial obligations. The need to prove adequate financial means to support themselves was a difficult task for some participants, often delaying the process of becoming a resident. One woman shared her struggles, stating, ‘They asked to prove financial means but did not accept the papers from my country. It took me 1 year to get all the papers together’ [27, Latina, Peru]. Another said that her ‘request for residency was denied for not having enough funds. Re-applied this year and still waiting for approval’ [30, White, Uruguay]. Participants highlighted that they had ‘to pay for very expensive health insurance’ [59, Latina, Chile], and some simply stated ‘money’ as one of their barriers. For many women, the challenge of proving that they had the financial means to support themselves was exacerbated by visa restrictions that prevented them from working:

‘I do not have a work contract and I had a study visa, which did not allow me to work’

[32, Latina, Dominican Republic].

In addition to the financial requirements, a number of women faced the challenge of needing to present an employment contract before arriving in the country, which was not always easily attainable. Participants noted that the immigration office ‘asked for an employment contract before coming here’, that they needed ‘to be hired by an employer’ and that it was ‘difficult to get a job’. One respondent highlighted, ‘The workplaces are not willing to make a 40-h contract, which is a requirement in foreign countries’ [22, Latina, Honduras]. Furthermore, some participants encountered logistical complexities that significantly impacted their progress. For instance, one participant had to apply for a visa from her home country, which incurred significant time and financial burdens:

‘I had to apply for a visa from Colombia, despite being in Spain legally. They did not accept my documents and I had to travel to Colombia from one day to the next. It cost a lot of money.’

[32, Latina, Colombia]

For some women, they simply had not resided in Spain long enough to be eligible to apply for residency. One woman said ‘I need one year of residence to be eligible for residency’ [29, Latina, Colombia]. This was echoed by other women who said that they ‘do not have the stipulated time to apply’ or ‘do not yet have the required length of stay’. The required length of stay to obtain residency appeared to differ for different women, perhaps depending on the route through which they were applying, or suggesting a lack of clarity in the information women were receiving. In order to obtain permanent residency in Spain, it is necessary to reside in the country continuously for 5 years (

Government of Spain 2023). Some women appeared to be in this process: ‘I am waiting until I am eligible after 5 years’ [37, Black, Zimbabwe]; however, others appeared to have different information:

‘I shall meet the criteria after my third year working as an English teacher/auxiliary’

[35, Latina, South America].

Another route to obtaining residency in Spain is through the ‘Arraigo Social’, or Social Roots visa. This allows for individuals who have been living in Spain undocumented for a minimum of three years to apply for residency if they can meet certain requirements (

Government of Spain 2023). A number of respondents were applying for their residency through this route. Some women had attempted to apply for their residency through various different routes, which highlights the complexity of the process and the challenge that many face in meeting all the necessary requirements:

‘I have submitted 3 times the residence application. (1) Arraigo Social, yes, I needed a work contract because I had my own income, and it was NOT favourable. (2) Non-lucrative visa, they told me no. (3) Now I am presenting through a study visa.’

[56, Latina, Argentina]

Supporting the finding from the quantitative data that challenges in meeting the requirements is a significant burden, this theme underscores the difficulties that individuals face while attempting to meet specific criteria or fulfil certain conditions during the residency process. These challenges often arise due to incomplete documentation, hard-to-satisfy prerequisites, and limitations imposed by financial and legal and logistical obligations.

While many of these requirements are standard immigration procedures, it is essential to acknowledge that they can create additional barriers for many individuals and exacerbate inequalities by disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable groups. Addressing these challenges and finding ways to mitigate their impact is crucial to ensuring a more inclusive and accessible residency process for all applicants.

3.5. Interpersonal Communication with Public Officials

Respondents highlighted the interpersonal dynamics they experienced during the residency and immigration process, particularly concerning interactions with the street-level bureaucrats working in immigration administration—specifically, the clerks and administrative staff based in the various ‘Oficinas de Extranjeria’ (foreigners/immigration offices) involved with the in-person processing of visa applications.

Supported by the quantitative findings, which showed that a significant proportion of respondents faced language barriers during their application process, the qualitative data highlighted again that language differences and communication breakdowns were prominent challenges that impacted the effectiveness of interactions throughout the process.

Holzinger (

2020) suggested that language barriers in the migration process and a lack of strategies to deal with linguistic diversity are less an accepted fact and more ‘socially constructed and contingent’ outcomes of the contexts created within institutions (

Holzinger 2020).

Some respondents cited facing general ‘communication barriers’, while others specifically pointed out difficulties in communicating with administrative staff in the immigration offices. One participant expressed her frustration, commenting on the ‘Inaccessibility of officials. [It’s like] talking to robots.’ [73, Latina, El Salvador]. The breakdown in communication often led to further confusion and added to the challenge of navigating unclear and complex procedures. Participants noted receiving inconsistent and even contradictory information from different staff members, contributing to the sense of uncertainty:

‘Unclear and even contradictory information re: process and requirements. Changed every time I talked to someone different’

[44, Multiple ethnicities, Canada]

A recurring observation was that individual clerks seemed to wield considerable influence over the process, leading to discrepancies in handling cases. Some participants observed that the official processes seemed rather informal and reliant on the discretion of the individual handling the case, contributing to a lack of clarity and efficiency:

‘Many of Valencia’s official processes seem very laid back and up to the discretion of whatever person you’re dealing with at that moment. Instructions are not very clear’

[25, Latina, USA].

Others highlighted how ‘sometimes it seems like everything depends on the individual clerk’ [38, White, Hungary] and that they would receive ‘different information [at] each meeting’

[52, White, Sweden].

This ties in with the findings from the earlier theme from

Section 3.3 on challenges in accessing information and the complex administrative processes, demonstrating that unclear systems, processes, and a lack of information generally are exacerbated by the street-level bureaucrats that applicants encounter in the process. Participants expressed concerns about the competence and training of administrative staff, with some ‘funcionarios [civil servants] requesting documents that are not required by the law’ [34, White, Russia]. Furthermore, a ‘lack of knowledge on the subject on the part of foreign officials’ [37, White, USA], or those working in immigration administration, added to the difficulties faced by applicants, as it prolonged and complicated the process. In some cases, the dissatisfaction with the administration of residency applications extended beyond the clerks working in immigration offices to other street-level bureaucrats. For example, one woman who was trying to apply for a visa through the exceptional circumstances route, due to being a victim of gender-based violence, cited a ‘lack of training in gender-based violence for the lawyer who filed my asylum application documents for continuous GBV’ [45, Latina, Venezuela] as a barrier to residency.

Whilst in some cases a lack of knowledge or training may have explained the confusing and inconsistent information imparted by administrative staff, these findings are supported by the wider literature on street-level bureaucrats that highlights how the use of discretionary power can influence access to relevant, important and consistent information, particularly in immigration settings (

Alpes and Spire 2013;

Bastien 2009;

Borrelli and Andreetta 2019;

Lipsky 2010).

Even individuals who did not encounter language barriers noted challenges in the process. This highlights the significant burdens that many applicants face, which are compounded for those not proficient in the language:

‘Bureaucracy and paperwork in general is extremely tedious, even when you know the language’

[35, White, UK]

Aside from communication barriers, respondents also raised issues regarding the demeanour of administrative staff. Instances of rudeness and unhelpfulness were reported in interactions. One participant expressed her dissatisfaction, stating her experience with ‘very unpleasant office clerks’ [35, White, Hungary] and another, the ‘lack of respect by public immigration workers’ [36, White, Finland]. One woman remarked that she stopped seeking help from certain places due to the fear of receiving more ‘rejection from civil servants’ [27, Latina, Colombia]. Some participants perceived differential treatment based on their non-citizen status and described feeling disrespected and undervalued during the process:

‘Undignified treatment. I felt in the process that I was treated differently for not being a citizen’

[26, Latina, Nicaragua].

Others specifically mentioned mistreatment, xenophobia and discrimination in their interactions with administrative staff in the immigration system. This again reflects the literature on street-level bureaucrats attached to immigration systems that highlights how value and social judgements are often used in the upholding or subversion of the law. This can be impacted by consciously and subconsciously held beliefs about deservingness based on gender, racial, cultural and religious biases, among others (

Alpes and Spire 2013;

Ratzmann and Sahraoui 2021). One study conducted in non-governmental organisations in Andalusia found that racist gatekeeping played a significant role in staff members’ decision-making about who would receive help or not (

Rogozen-Soltar 2012), and another found that some civil servants working at the Asylum and Refugee Bureau in Spain would alter the questions they asked or the notes they took when interviewing applicants based on previous judgements they had made about whether it was a good or bad case (

Bastien 2009).

Whilst participants did not disclose how they responded to their challenging interactions with street-level bureaucrats, other studies have suggested that migrants are likely to respond in one of five main ways: Exiting the situation, such as by trying to subvert formal systems or switch service provider; Voicing their concerns through complaints or speaking up; Remaining loyal to the street-level bureaucrat by continuing with the process without speaking up; Neglecting the situation by becoming indifferent; or Gaming the system by trying to exploit or manipulate the rules in their favour (

Schierenbeck et al. 2023). Whilst formal complaint procedures to raise concerns with civil servants in Spain exist, they are unlikely to be used in the context of immigration procedures given the precarious status of the applicants, the inherent power imbalance and the extent to which street-level bureaucrats acting in this field are ‘protected from external examination’ and ‘empowered to interpret and apply legal texts and regulations without, in most cases, having to fear administrative appeals’ (

Alpes and Spire 2013).

This theme highlights the complexity and challenges that arise when interacting with administrative staff during the immigration process. It underscores the significance of effective communication and addresses potential issues arising from a lack of training, negative behaviour and discriminatory attitudes exhibited by some street-level bureaucrats. The presence of language barriers further complicated interactions, leading to potential misunderstandings and hindering communication.

3.6. Strategies Adopted by Women Migrants to Cope with the Hurdles

The costs associated with bureaucratic violence have been conceptualised into three main categories: ‘learning costs’, which include the effort required to access all the necessary information about application processes and systems; ‘compliance costs’, which refer to the required financial resources, effort and time to complete application processes and comply with pre-requisites; and ‘psychological costs’, which include the ‘emotional burden associated with these processes’ (

Moynihan et al. 2015;

Schmidt et al. 2023). The challenges and barriers faced in the process of applying for residency described in

Section 3.3,

Section 3.4 and

Section 3.5 carry with them one or more of these costs. Confusing and cumbersome administrative systems and a lack of clear information on the application process are associated with the learning costs of attempting to find the relevant information in order to proceed with residency applications. The difficulties faced in meeting the stringent visa requirements carry compliance costs as applicants attempt to gather the necessary paperwork and proof, which requires time, effort and money. The stress of dealing with learning and compliance costs are likely to lead to psychological costs, which will be further exacerbated by challenging or traumatic interactions with street-level bureaucrats. In a study of experiences navigating the immigration system for migrants in Canada, Schmidt and colleagues found that ‘The feeling of being at the mercy of an opaque and powerful bureaucracy had a detrimental impact on the emotional wellbeing of many of the interviewees, leading to stress, mental fatigue and a sense of being overwhelmed’ (

Schmidt et al. 2023).

Various strategies were employed by applicants to overcome the challenges posed by the residency application system and to reduce the associated costs involved. Participants shared different solutions, including seeking assistance from professional advisors (gestors) or employers, as well as relying on support from partners, friends or family members to facilitate the application process. For those who had the opportunity to seek support, it proved beneficial in reducing barriers to obtaining residency. However, some individuals also acknowledged their privilege in being able to access such support:

‘I was lucky to be privileged enough to hire a gestor’

[58, White, Germany]

Some applicants sought help from professional advisors, or gestors, to navigate the intricacies of the residency application process. The expertise of these professionals assisted them in understanding the requirements, gathering the necessary documentation, and handling bureaucratic complexities more effectively, in addition to increasing their chances of securing an application appointment, as previously discussed. Some individuals also relied on their employers to assist them with the application, which streamlined the process and minimised potential obstacles. As one participant stated, ‘I didn’t face any barriers because my employer did the application for me’ [27, White, The Netherlands].

Participants highlighted the significance of support from their social network, namely, partners, friends or family members. This support network played a crucial role in providing guidance, emotional assistance, and practical help throughout the application process. By relying on the expertise and resources of their social connections, some applicants were able to overcome hurdles and successfully progress in their residency journey. This finding is in contrast to the quantitative data, which did not show an association between social support and a reduced likelihood of barriers in the multivariable analysis. However, at the univariable level, women who reported having social support were less likely to have experienced a barrier than women who did not have support.

In some cases, individuals found their residency process eased by being married to a European or Spanish citizen. Marriage became a strategic approach to resolve the challenges faced by the application process, even if it meant marrying earlier than planned. By formalising their romantic relationships, these applicants were able to access certain benefits and streamlined procedures related to residency. One participant shared her experience, saying, ‘Since we were not married at the time, it was harder for me to access residencia than my (now) husband. We married to make the paperwork easier!’ [42, White, UK].

Overall, this theme sheds light on the diverse strategies people employ to navigate the residency application process successfully. However, these strategies predominantly favour individuals with specific privileges or social status, leaving the most vulnerable migrants without viable means to reduce their barriers to residency, which could thereby exacerbate inequalities.

This section delved into the qualitative comments provided by respondents to give more detail on the barriers faced during their residency application process and the reasons why they still may not have resident status. The themes that emerged highlighted the intricate and confusing systems associated with applying for residency in Spain. Participants encountered bureaucratic hurdles and administrative complexities, leading to frustration and confusion. The lack of clear and concise information exacerbated the challenges, leaving applicants grappling with the ambiguous guidelines. Communication barriers, as well as experiences of mistreatment and discrimination from street-level bureaucrats, further hindered effective interactions, adding to the complexity of the process. Respondents appeared to be equally frustrated by the bureaucratic and legal barriers that they faced, as they were with the behavioural barriers of street-level bureaucrats created by the space under Spanish law within which they were able to exercise discretion in the processing of applications. Despite these difficulties, some applicants sought solutions through professional advice and support from their social network, but it was evident that these strategies were often only available to individuals with specific privileges.

4. Discussion

The findings presented in this study provide valuable insights into some of the barriers faced by migrant women in the process of applying for residency in Spain, as well as how these barriers differ by socio-demographic characteristics. The results highlight significant disparities among different groups of migrant women and shed light on the challenges experienced by many seeking residency in Spain.

The majority of respondents had faced at least one barrier during the application process; the most commonly reported was a lack of information, indicating that the residency process is complex and difficult to navigate. This was supported by the findings from the qualitative data, which highlighted complicated, unclear processes and a lack of information as significant challenges and sources of frustration for migrant women. Another study of migration networks between Romania and Spain found that Romanian migrants who did not already have family living in Spain found it very difficult to migrate because of the lack of information, alongside the high costs involved (

Elrick and Ciobanu 2009). Whilst these challenges could be attributed to the innocuous systems of a country that has long displayed a bloated bureaucracy (

Chislett 2018), the considerable and ongoing barriers may also be strategic. Borelli and colleagues highlight that ‘bureaucracy has become one of the main aspects of the migration and asylum infrastructure regulating entry, permanence and access to welfare in receiving countries’ (

Borelli et al. 2023). Anti-immigrant sentiment has become more pronounced globally in recent years, including within Spain (

López Sala et al. 2021;

Olmos and Garrido 2012), and many countries are displaying ‘national interest postures’ that further add to the barriers that migrants face (

World Economic Forum 2022).

Women from Africa, Asia or the Middle East not only faced a higher likelihood of encountering barriers in the residency compared to women from Europe, but they also had a higher chance of facing multiple barriers. Discrimination, not being able to meet requirements for residency, and language barriers, were more prevalent for them than for women from other regions. These findings suggest a disturbing trend of discrimination within the residency application process, which is reinforced by the qualitative comments, revealing instances of discrimination, xenophobia and mistreatment during interactions with street-level bureaucrats.

Despite having laws in place to protect against it, systemic racism and discrimination persist within Spain (

Rodríguez-García 2022). This issue has been documented within the public administration system, as evidenced by a study focusing on African and Afro-descendent populations in Spain. Respondents highlighted that after ‘society in general’ and the workplace, public authorities were the place where they experienced most discrimination due to their nationality (

Cea D’Ancona and Martinez 2021). In addition, a study on NGO workers in Granada found that decision-making and the provision of services to aid migrants was based on racist stereotypes that dictated views on deservingness (

Rogozen-Soltar 2012) and that the responses of street-level bureaucrats to migrant cases based in Spanish immigration offices were dependent on pre-conceived notions about the client (

Bastien 2009). Moreover, racism and discrimination pose significant challenges for migrants in various aspects of their lives, including access to housing, education, the labour market and healthcare (

Agudelo-Suárez et al. 2009;

Cea D’Ancona and Martinez 2021;

Provivienda 2022;

Rodríguez-García 2022;

Solanes Corella 2015). This discrimination has also been cited as a strategy with which to protect borders and uphold colonial legacies within the immigration process (

Borelli et al. 2023).

The bureaucratic burdens associated with residency applications have a direct and significant impact on the lives of migrants. This raises the stakes involved with applying for residency and creates situations of bureaucratic violence due to the structural and legal violence inherent in state systems that maintain social inequalities and legitimise the unequal power dynamics between migrants and street-level bureaucrats (

Schmidt et al. 2023). The qualitative findings highlighted a lack of clarity and contradictory information, particularly on the part of public administrative staff. These street-level bureaucrats often become gatekeepers to information, services, and the state more generally, particularly when policies are vague, left to the discretion of autonomous regions, as they often are in Spain, and can be open to interpretation (

Borelli et al. 2023;

Hsia and Gil-González 2021). Situating this within the context of an inherently discriminatory system creates a scenario where the most vulnerable people will be left more exposed. For migrants, the perceptions and experiences of discrimination in the host country can lead to substantial stress and negatively impact their wellbeing (

Agudelo-Suárez et al. 2011;

García-Cid et al. 2020;

Szaflarski and Bauldry 2019). These factors therefore not only restrict migrant rights and increase their vulnerability, but also have far-reaching consequences for their overall welfare.

A number of other interesting associations were seen between socio-demographic characteristics and barriers in the residency process. Those with higher education qualifications were more likely to have experienced barriers, which could be influenced by the type of visa they were applying for, particularly if they are planning to work in Spain. This is supported by the fact that women who are not permitted to work due to visa restrictions were also more likely to have experienced barriers during their residency application process. Longer-term residents (over 10 years) were less likely to experience barriers in the residency process compared with women who had been in the country for a shorter period of time. This finding could be influenced by recall bias, as women who have been in the country longer might find it harder to recall specific details about their application process, or it could reflect an increasingly optimised and formalised system over time that creates additional bureaucratic hurdles for applicants (

Fintonelli and Rinken 2023). Women living with their parents or family were more likely to experience barriers in the residency process than those living alone. It is possible that these women were applying alongside multiple family members or were applying for family reunification visas, which could add complexity to the process. None of these associations were significant when considered against the number of barriers to residency, however, and could benefit from further investigation to develop a more comprehensive understanding.

In examining the findings of this study, it is crucial to acknowledge certain limitations that may impact the generalisability of the results. The survey was conducted on a non-probabilistic sample of migrant women living in the Valencian community. Participants were recruited via social media, which may have inadvertently excluded individuals who are less connected to online platforms, and the majority had resident status in Spain, were highly educated and had satisfactory income levels. As with all research with marginalised populations, it is important to consider the voices that remain unheard and underrepresented, including those from low-income households, those from marginalised ethnic groups, and those with irregular migrant status, and the additional barriers that may be faced by these more vulnerable women. Additionally, whilst the open-text boxes allow us to dig deeper into the experiences of various barriers to residency than would have been possible only with quantitative data, there is a level of nuance that is impossible to extract from short text comments, and therefore a deeper level of understanding may have been missed around the barriers faced whilst applying for residency in Spain, particularly for different sub-sets of migrant women. Further research should build on this work to add to the body of literature investigating migrant experiences of interacting with the immigration system in Spain. In particular, using more probabilistic methods of sampling for surveys relevant to hard-to-reach groups and conducting in-depth qualitative research to understand the nuance of the experiences for different migrant groups, how they respond to and cope with bureaucratic violence and its impact on their wellbeing in this context, would be beneficial.