A Multidimensional Understanding of the Relationship between Sexual Identity, Heteronormativity, and Sexual Satisfaction among a Cisgender Sample

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Queer Theory Framework

1.2. Sexual Attraction and Identity

1.3. Sexual Health Disparities

2. Methods

2.1. Sample and Procedures

2.2. Measurement

2.2.1. Sexual Identity

2.2.2. Heteronormativity

2.2.3. Sexual Satisfaction

3. Data Analysis Plan

4. Results

4.1. Preliminary Findings

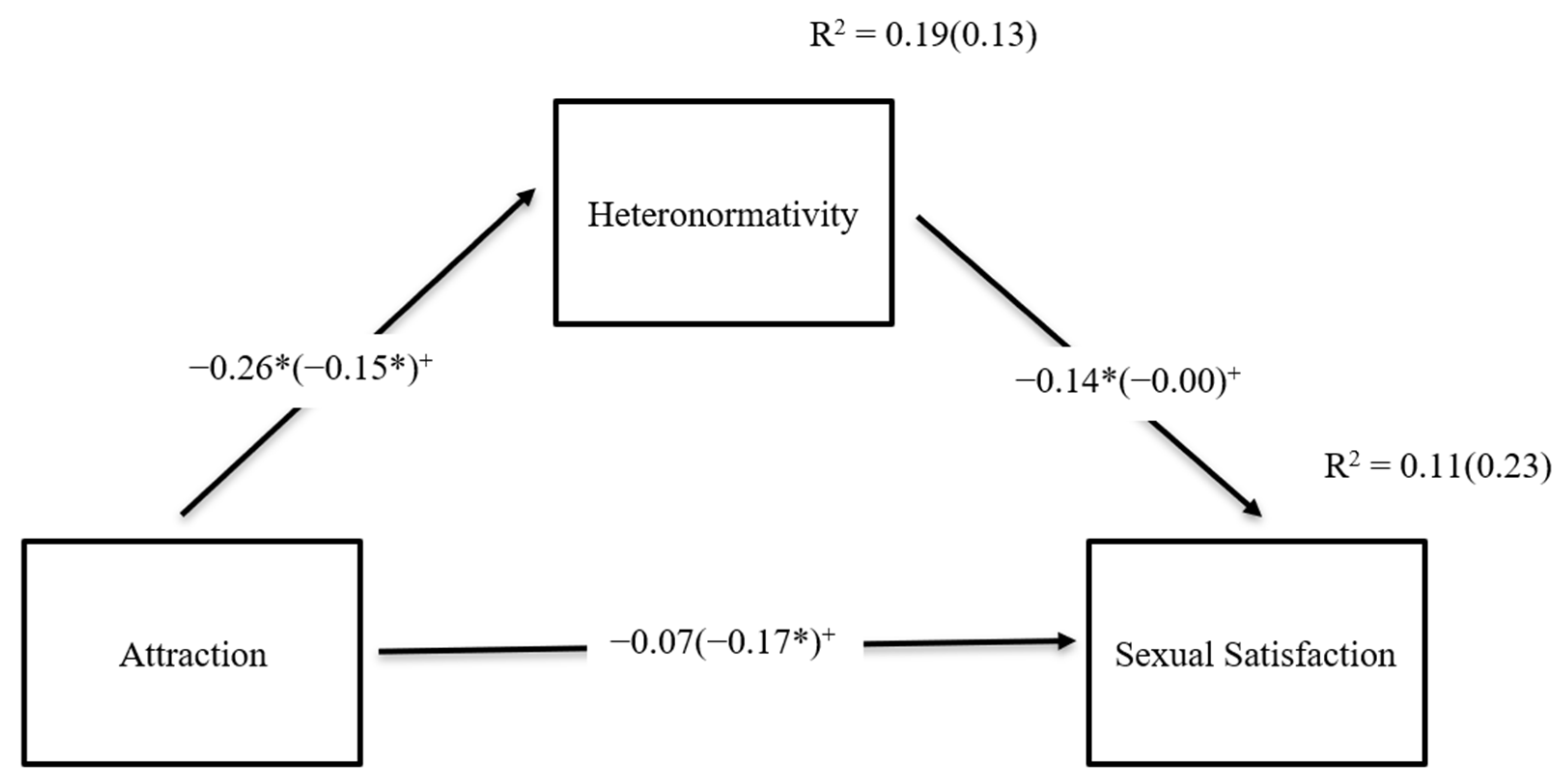

4.2. Results for the Hypothesized Model

5. Discussion

6. Limitations

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abes, Elisa S., and David Kasch. 2007. Using queer theory to explore lesbian college students’ multiple dimensions of identity. Journal of College Student Development 48: 619–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. 2020. Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahamondes, Joaquín, Jaime Barrientos, Mónica Guzmán-González, Lusmenia Garrido-Rojas, Fabiola Gómez, and Ricardo Espinoza-Tapia. 2023. The negative effects of internalized homonegativity on sexual satisfaction: Dyadic effects and gender-based differences in Chile. Journal of Lesbian Studies 27: 22–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldwin, Aleta, Debby Herbenick, Vanessa R. Schick, Brenda Light, Brian Dodge, Crystal A. Jackson, and J. Dennis Fortenberry. 2019. Sexual satisfaction in monogamous, nonmonogamous, and unpartnered sexual minority women in the US. Journal of Bisexuality 19: 103–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beyrer, Chris, Stefan D. Baral, Chris Collins, Eugene T. Richardson, Patrick S. Sullivan, Jorge Sanchez, Gift Trapence, Elly Katabira, Prof Michel Kazatchkine, Owen Ryan, and et al. 2016. The global response to HIV in men who have sex with men. The Lancet 388: 198–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bionat, Justin F.C. 2019. Narratives from over the Rainbow: Health Disparities, Sexual Health Care, and Being Gay, Bisexual and ‘MSM’ (Men WHO have Sex with Men) in Cambodia. Doctoral dissertation, Mahidol University, Nakhon Pathom, Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- Birnbaum, Michael H. 2004. Human research and data collection via the Internet. Annual Review of Psychology 55: 803–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Björkenstam, Carl, Lena Mannheimer, Maria Löfström, and Charlotte Deogan. 2020. Sexual orientation–related differences in sexual satisfaction and sexual problems—A population-based study in Sweden. The Journal of Sexual Medicine 17: 2362–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, Judith. 1990. Gender trouble. In Feminism/Postmodernism. Edited by Linda Nicholson. London: Routledge, pp. 324–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Centers for Disease Control [CDC]. 2021. Sexually Transmitted Infections Treatment Guidelines, 2021; Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control.

- Cheong, JooSeok, and David P. MacKinnon. 2012. Mediation/indirect effects in structural equation modeling. In Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling. Edited by R. H. Hoyle. New York: The Guilford Press, pp. 417–35. [Google Scholar]

- Chevrette, Roberta. 2013. Outing heteronormativity in interpersonal and family communication: Feminist applications of queer theory, beyond the sexy streets. Communication Theory 23: 170–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lauretis, Teresa. 1991. Queer theory: Lesbian and gay sexualities. Differences 3: iii–xviii. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erickson-Schroth, Laura, and Jennifer Mitchell. 2009. Queering queer theory, or why bisexuality matters. Journal of Bisexuality 9: 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinstein, Brian, Manuel Hurtado, Jr., Christina Dyar, and Joanne Davila. 2023. Disclosure, minority stress, and mental health among bisexual, pansexual, and queer (Bi+) adults: The roles of primary sexual identity and multiple sexual identity label use. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 10: 181–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Few-Demo, AprilL., and Katherine R. Allen. 2020. Gender, feminist, and intersectional perspectives on Families: A decade in review. Journal of Marriage and Family 82: 326–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finer, Lawrence B., and Mia R. Zolna. 2016. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States 2008–2011. The New England Journal of Medicine 374: 843–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fish, Jessica, and Stephen T. Russell. 2018. Queering methodologies to understand queer families. Family Relations 67: 12–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleary, Sasha A., Claudio R. Nigg, and Karen M. Freund. 2018. An examination of changes in social disparities in health behaviors in the US, 2003–2015. American Journal of Health Behavior 42: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foucault, Michel. 1990. The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Galupo, M. Paz, Shane B. Henise, and Nicholas L. Mercer. 2016. “The labels don’t work very well”: Transgender individuals’ conceptualizations of sexual orientation and sexual identity. International Journal of Transgenderism 17: 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaskin, James. 2012. Group Differences. Stats Tools Package. Available online: http://statwiki.kolobkreations.com/ (accessed on 23 April 2023).

- Gelinas, Luke, Robin Pierce, Sabune Winkler, I. Glenn Cohen, Holly Fernandez Lynch, and Barbara E. Bierer. 2017. Using social media as a research recruitment tool: Ethical issues and recommendations. The American Journal of Bioethics 17: 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gezgin, Elif. 2023. Between Privileges and Sacrifices: Heteronormativity and Turkish Nationalism in Urban Turkey. Journal of Homosexuality 70: 2072–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glynn, Tiffany R., Don Operario, Madeline Montgomery, Alexi Almonte, and Philip A. Chan. 2017. The duality of oral sex for men who have sex with men: An examination into the increase of sexually transmitted infections amid the age of HIV prevention. AIDS Patient Care and STDs 31: 261–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golder, Scott A., and Michael W. Macy. 2014. Digital footprints: Opportunities and challenges for social research. Annual Review of Sociology 40: 129–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Habarth, Janice M. 2015. Development of the heteronormative attitudes and beliefs scale. Psychology & Sexuality 6: 166–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, Donald E. 2003. Queer Theories. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Hambour, Victoria K., Amanda L. Duffy, and Melanie J. Zimmer-Gembeck. 2023. Social identification dimensions, sources of discrimination, and sexuality support as correlates of well-being among sexual minorities. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammack, Phillip L., Sam D. Hughes, Julianne M. Atwood, Elliot M. Cohen, and Richard C. Clark. 2021. Gender and sexual identity in adolescence: A mixed-methods study of labeling in diverse community settings. Journal of Adolescent Research 37: 167–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heiman, Julia, J. Scott Long, Shawna N. Smith, William A. Fisher, Michael S. Sand, and Raymong C. Rosen. 2011. Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior 40: 741–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, Jenny A., Margo Mullinax, James Trussell, J. Kenneth Davidson Sr, and Nelwyn B. Moore. 2011. Sexual satisfaction and sexual health among university students in the United States. American Journal of Public Health 101: 1643–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hosking, Warwick. 2012. Satisfaction with open sexual agreements in Australian gay men’s relationships: The role of perceived discrepancies in benefit. Archives of Sexual Behavior 42: 1309–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurlbert, David Farley, L. Cynthia White, R. David Powell, and Carol Apt. 1993. Orgasm consistency training in the treatment of women reporting hypoactive sexual desire: An outcome comparison of women-only groups and couples-only groups. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry 24: 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iasenza, Suzanne. 2010. What is queer about sex? Expanding sexual frames in theory and practice. Family Process 49: 291–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaestle, Christine E. 2019. Sexual orientation trajectories based on sexual attractions, partners, and Identity: A longitudinal investigation from adolescence through young adulthood using a U.S. representative sample. The Journal of Sex Research 56: 811–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnish, Kelly K., Donald Stephen Strassberg, and Charles Turner. 2005. Sex differences in the flexibility of sexual orientation: A multidimensional retrospective assessment. Archives of Sexual Behavior 34: 173–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, Celia. 2005. Heteronormativity in action: Reproducing the heterosexual nuclear family in after-hours medical calls. Social Problems 52: 477–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knight, Rod, Jean A. Shoveller, John L. Oliffe, Mark Gilbert, and Shira Goldenberg. 2012. Heteronormativity hurts everyone: Experiences of young men and clinicians with sexually transmitted infection/HIV testing in British Columbia, Canada. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 17: 441–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuru-Utumpala, Jayanthi. 2013. Butching it up: An analysis of same-sex female masculinity in Sri Lanka. Culture, Health & Sexuality 15: S153–S165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Joseph T. F., Jean. H. Kim, and Hi Yi Tsui. 2005. Mental health and lifestyle correlates of sexual problems and sexual satisfaction in heterosexual Hong Kong Chinese population. Urology 66: 1271–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lawrance, Kelli-An, and Elaine Sandra Byers. 1995. Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The Interpersonal Exchange Model of sexual satisfaction. Personal Relationships 2: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mark, Kristen P., Michael D. Toland, Dani E. Rosenkrantz, Holly M. Brown, and Sang -hee Hong. 2018. Validation of the sexual desire inventory for lesbian, gay, bisexual, Trans, and queer adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 5: 122–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matacotta, Joshua J., Francisco J. Rosales-Perez, and Christian M. Carrillo. 2020. HIV preexposure prophylaxis and treatment as prevention—Beliefs and access barriers in men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women: A systematic review. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews 7: 265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo, Cris. 2013. Unsettled relations: Schools, gay marriage, and educating for sexuality. Educational Theory 63: 543–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, Seth, and Nicole Elias. 2023. Rainbow research: Challenges and Recommendations for sexual orientation and gender identity and expression (SOGIE) survey design. Voluntas 34: 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, Jonathan J., and Christopher A. Daly. 2008. Sexual minority stress and changes in relationship quality in same-sex couples. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 25: 989–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Laboy, M., J. Garcia, P. A. Wilson, R. G. Parker, and N. Severson. 2014. Heteronormativity and sexual partnering among bisexual Latino men. Archives of Sexual Behavior 44: 895–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Mustanski, Brian, Michelle Birkett, George J. Greene, Margaret Rosario, Wendy Bostwick, and Bethany G. Everett. 2014. The association between sexual orientation identity and behavior across race/ethnicity, sex, and age in a probability sample of high school students. American Journal of Public Health 104: 237–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orellana, Ligia, Tatiana Alarcón, and Berta Schnettler. 2022. Behavior without beliefs: Profiles of heteronormativity and well-being among heterosexual and non-heterosexual university students in chile. Frontiers in Psychology 13: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrillo, Brandon T., and Randall D. Brown. 2021. Sexual Communication Between Queer Partners. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Communication. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pascoal, Patricia M., Krystelle Shaughnessy, and Maria Joana Almeida. 2019. A thematic analysis of a sample of partnered lesbian, gay, and bisexual people’s concepts of sexual satisfaction. Psychology & Sexuality 10: 101–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Eric R., and Jeremy Kurz. 2016. Using Facebook for health-related research study recruitment and program delivery. Current Opinion in Psychology 9: 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Beatriz, Maria Teresa Ramiro, and Jaime Barrientos. 2023. Editorial: Victimization in sexual and reproductive health: Violence, coercion, discrimination, and stigma. Frontiers in Psychology 14: 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollitt, Amanda M., Sara E. Mernitz, Stephen. T Russell, Melissa A. Curran, and Russell B. Toomey. 2019. Heteronormativity in the lives of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and queer young people. Journal of Homosexuality 68: 522–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul Poteat, V., Stephen T. Russell, and Alexis Dewaele. 2019. Sexual health risk behavior disparities among male and female adolescents using identity and behavior indicators of sexual orientation. Archives of Sexual Behavior 48: 1087–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Raymond C., Joseph Catania, Lance Pollack, Stanley Althof, Michael O’Leary, and Allen D. Seftel. 2004. Male Sexual Health Questionnaire (MSHQ): Scale development and psychometric validation. Urology 64: 777–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubinsky, Valerie, and Angela Hosek. 2020. “We have to get over it”: Navigating sex talk through the lens of sexual communication comfort and sexual self-disclosure in LGBTQ intimate partnerships. Sexuality & Culture 24: 613–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rust, Paula C., and Paula C. Rodriguez Rust. 2000. Bisexuality in the United States: A Social Science Reader. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Salomaa, Anna, Jes Matsick, Cara Exten, and Mary Kruk. 2023. Different categorizations of women’s sexual orientation reveal unique health outcomes in a nationally representative U.S. sample. Women’s Health Issues 33: 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacker, Randall. E., and Richard G. Lomax. 2010. A Beginner’s Guide to Structural Equation Monitoring. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Sedgewick, Eve. 1990. The Epistemology of the Closet. Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Shepler, Dustin K., Jared M. Smendik, Kate M. Cusick, and David R. Tucker. 2018. Predictors of sexual satisfaction for partnered lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity 5: 25–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoptaw, Steven, Robert E. Weiss, Brett Munjas, Christopher Hucks-Ortiz, Sean D. Young, Sherry Larkins, Gregory D. Victorianne, and Pamina M. Gorbach. 2009. Homonegativity, substance use, sexual risk behaviors, and HIV status in poor and ethnic men who have sex with men in Los Angeles. Journal of Urban Health 86: 77–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Sprecher, Susan, and Susan Hendrick. 2004. Self-disclosure in intimate relationships: Associations with individual and relationship characteristics over time. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 23: 836–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urban, Jennifer B., and Brad van Eeden-Moorefield. 2018. Designing and Proposing Your Research Project. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valocchi, Stephen. 2005. Not yet queer enough. Gender & Society 19: 750–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela, Maria do Mar Castro, Nikita Dhawan, and Antke Engel, eds. 2016. Hegemony and Heteronormativity: Revisiting ‘the Political’ in Queer Politics. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Velten, Julia, and Jurgen Margraf. 2017. Satisfaction guaranteed? how individual, partner, and relationship factors impact sexual satisfaction within partnerships. PLoS ONE 12: e0172855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walker, David A., and Thomas J. Smith. 2017. Computing robust, bootstrap-adjusted fit indices for use with nonnormal data. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 50: 131–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, Daniel Noam. 2004. Towards a queer research methodology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 1: 321–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, Margaret, Brooke Wells, Christina Ventura-DiPersia, Audrey Renson, and Christian Grov. 2017. Measuring sexual orientation: A review and critique of U.S. data collection efforts and implications for health policy. The Journal of Sex Research 54: 507–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeeman, Laetitia, Kay Aranda, and Alec Grant. 2013. Queer challenges to evidence-based practice. Nursing Inquiry 21: 101–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, Yao, and Anna Madill. 2018. The heteronormative frame in Chinese Yaoi: Integrating female Chinese fan inter views with Sinophone and Anglophone survey data. Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 9: 435–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Demographic Characteristic | Queer Respondents (n = 165) | Non-Queer Respondents (n = 291) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 37.93(SD = 11.48) | 34.86(SD = 11.20) | |

| Gender | Cisgender, female | 44.80% | 84.90% |

| Cisgender, male | 55.20% | 15.10% | |

| Race | Black, Afro-Caribbean, African American | 1.33% | 2.40% |

| East Asian or Asian American | 3.60% | 1.38% | |

| Hawaiian, Pacific Islander | 0.00% | 1.00% | |

| Latinx, Hispanic, Hispanic American | 6.67% | 5.50% | |

| Middle Eastern or Arab American | 1.00% | 1.03% | |

| Native American, Alaskan Native | 1.33% | 2.06% | |

| Non-Hispanic White, Caucasian | 83.03% | 84.54% | |

| South Asian, Indian American | 1.00% | 1.00% | |

| Multiracial | 4.67% | 2.06% | |

| Relationship Status | No regular partner | 32.7% | 18.60% |

| Regular partner | 67.30% | 81.40% | |

| Income | Under $25,000 | 14.50% | 6.90% |

| $25,000–49,999 | 19.40% | 12.40% | |

| $50,000–74,999 | 21.20% | 22.10% | |

| $75,000–99,999 | 13.30% | 19.30% | |

| $100,000–124,999 | 9.70% | 15.50% | |

| $125,000 or more | 21.30% | 23.80% | |

| Education | Did not complete high school | 2.40% | 0.30% |

| High school/GED | 6.70% | 3.80% | |

| Some college | 9.70% | 9.30% | |

| Associate’s degree/Trade degree | 6.70% | 5.90% | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 31.50% | 36.10% | |

| Master’s degree | 29.10% | 30.90% | |

| Doctorate or other advanced degree above a master’s | 13.90% | 13.70% | |

| Variable | Attraction | Heteronormativity | Sexual Satisfaction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attraction | - | −0.24 ** | −0.00 |

| Heteronormativity | −0.16 ** | - | −0.15 * |

| Sexual Satisfaction | −0.19 ** | 0.02 | - |

| Mean | 1.61(1.28) ** | 34.65(43.72) ** | 19.52(20.94) * |

| SD | 0.71(0.45) | 14.51(19.09) | 7.29(6.70) |

| Range | 2(1) | 70(103) | 27(24) |

| Alpha | - | 0.87(0.92) | 0.94(0.93) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

van Eeden-Moorefield, B.; Cooke, S.; Bible, J.; Gyan, E. A Multidimensional Understanding of the Relationship between Sexual Identity, Heteronormativity, and Sexual Satisfaction among a Cisgender Sample. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090527

van Eeden-Moorefield B, Cooke S, Bible J, Gyan E. A Multidimensional Understanding of the Relationship between Sexual Identity, Heteronormativity, and Sexual Satisfaction among a Cisgender Sample. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(9):527. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090527

Chicago/Turabian Stylevan Eeden-Moorefield, Brad, Steph Cooke, Jacqueline Bible, and Elvis Gyan. 2023. "A Multidimensional Understanding of the Relationship between Sexual Identity, Heteronormativity, and Sexual Satisfaction among a Cisgender Sample" Social Sciences 12, no. 9: 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090527

APA Stylevan Eeden-Moorefield, B., Cooke, S., Bible, J., & Gyan, E. (2023). A Multidimensional Understanding of the Relationship between Sexual Identity, Heteronormativity, and Sexual Satisfaction among a Cisgender Sample. Social Sciences, 12(9), 527. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12090527