1. Introduction

In the Philippines, a broad range of actors has recently become more active in debates about the nature and legacies of Marcos’ Martial Law era (1971–1981/1986).

1 They are responding to the ‘weaponization of memory’ and attempts at ‘forcible forgetting’ (

Human Rights Council 2020). Unlike the first wave of truth and memory initiatives that emerged in the immediate post-Marcos years and that prioritized the establishment of memorials and public monuments to commemorate the violence and injustice, the current wave of initiatives adopts a broader variety of approaches to the practice of truth-telling and memorializing: from living libraries and oral history projects to social media campaigns or Wikipedia

editathons. This has led to a complex and dynamic ecology of truth and memorialization initiatives including material and immaterial practices, formal institutionalized and informal grassroots work, and ad hoc as well as long-term interventions, all geared towards shaping collective memories about the violent past.

This article is empirically grounded in interviews with 27 (cultural) practitioners, activists, and artists active in the domain of memory, truth, and justice. As such, their demographic profile to some extent overlapped, in that most interviewees were formally educated and active in the realm of social justice. Their ages varied significantly, with both victims of the Marcos regime as well as younger generations being represented. Some people were interviewed multiple times. Interviewees were selected on the basis of purposive snowballing. Interviews took place in person in Manila and online in the Fall and Winter of 2022–2023 and lasted just above one hour on average. The interviews followed the ethics procedures approved by the European Research Council. Questions varied slightly depending on the profile of the interviews, but always covered interviewees’ relation to memory activism, their role in and perspectives of the specific project they worked on, and how they understood that project in light of a broader transitional justice movement. In addition, primary documents and materials were analyzed and various cultural events were attended, such as exhibitions, movie screenings, commemorative events, or round tables.

The article explores and theorizes how the interaction between place-based and non-place-based truth and memorialization practices, and the nature of the process itself, jointly affect how memories of a violent past are constituted, contested, imagined, transformed—and sometimes erased. Below, I first present theoretical debates undergirding this article and then briefly describe the societal context, before discussing the Weaving Women’s Words on Wounds of War project, and reflecting on how it can inform our understanding of how difficult truths can be ‘presenced’ and listened to.

2. Theoretical Framework: Memory and Truth in Transitional Contexts

This section introduces the debates taking place at the intersection of scholarship on memory, truth, art, and resistance in contexts where there has been a political transition. The notions of memory and truth in particular are central to this article, and to the context of the Philippines, as I will show in the next section. While the scholarly literature on both memory and truth is dense and dynamic and spans a range of disciplines, I will narrow the discussion here to debates about truth and memory in post-dictatorial or post-conflict settings dealing with legacies of violent pasts. This makes transitional justice scholarship a useful, if not the only possible, lens for exploring the relationship between and the societal effects of truth and memorialization initiatives (

Pablo De Greiff 2020).

Truth itself has been one of the main pillars of transitional justice since the domain was consolidated. Formal truth-finding mechanisms, such as state-sanctioned truth (and reconciliation) commissions, in particular, have a long and sound tradition in transitional justice scholarship and practice (

Zunino 2019). These formal mechanisms have from the start been complemented by informal truth initiatives that are typically driven by a range of actors with divergent identities, objectives, and approaches (e.g.,

REMHI 2003;

Fulchirone 2009). Critical transitional justice scholars have decisively shifted the debate away from the initial exclusive focus on formal state-led truth mechanisms, towards more attention to the contributions of grassroots, hybrid and dynamic truth initiatives that sometimes propose new interpretations of how truth-finding should take place and how it may contribute to a culture of peace (

Evrard et al. 2021;

Firchow and Selim 2022). As a consequence, the inherent value and distinctive logic of these informal kinds of truth initiatives are increasingly acknowledged in transitional justice scholarship, and they are no longer treated as mere precursors or as second-best to formal initiatives (

Cohen 2020). Even if state involvement and acknowledgment continue to be important for many victims, informal truth practices can be potent because they may avoid the highly scripted nature of formal mechanisms, can typically better accommodate victims’ voices and needs, tend to allow for more complex narratives and experiences, and are less characterized by preferences for institutional closure or recognizable stories of ideal victim- and perpetratorhood. As such, while often initiated for pragmatic reasons, these informal truth initiatives hold potential for countering the epistemic injustice implicit in many formal truth initiatives by ‘presencing’ (ongoing) lived experiences of harm (

Herremans and Destrooper 2022).

Memorialization, too, has been part of the transitional justice ‘toolkit’ from the early days, even if it was only formally acknowledged as a fifth pillar of transitional justice in 2020 (

Human Rights Council 2020). This formal foregrounding of memorialization underlines its centrality for achieving transitional justice’s normative objectives of building cultures of peace. Moreover, its designation as a sui generis fifth pillar facilitates the examination of how memorialization interacts with other transitional justice initiatives, for example, in the domain of truth. Like truth initiatives, memory initiatives can be driven by states as well as non-state actors, and can be more or less formalized and institutionalized. While states in which violations of human rights have been committed have a duty to carry out memory processes, the ‘weaponization of memory’ and the tendency to manipulate information and memory in ways that encourage violence have pushed a growing number of non-state actors to also engage in memory work. These actors (from artists to victims’ collectives to international NGOs) often bypass the state and propose innovative and context-sensitive approaches to memorialization (

Human Rights Council 2020).

While there are significant differences within and between the domains of truth and memorialization, initiatives in both realms typically share the underlying assumption that knowing and acknowledging past violence helps citizens regain trust, both in the State and each other, and that this contributes to a democratic, inclusive, and peaceful society (

Human Rights Council 2020). In this sense, the notion of truth-finding has been interpreted as having a component of truth-seeking (e.g., through archival work or formal investigations), as well as truth-telling (e.g., through victim testimonies). This practice of truth-telling can also be observed within the domain of memorialization, for example, in initiatives like living libraries, oral history projects, or when victims tell their stories of harm during commemorative events. Whereas memorials and public monuments continue to be important manifestations of memorialization, they are increasingly complemented by these more dynamic truth practices that are premised on narrative approaches.

What has been missing from both fields of scholarship and practice, however, is a focus on what I will refer to as

truth-listening, i.e., questions of whether and how these difficult truths are listened to, how they operate in society, or how various approaches to truth-telling and memorialization interact differently with people’s pre-existing beliefs in the quest for more peaceful and just societies (

Arnould and Sriram 2014;

Stahn 2020). This notion of truth-listening, concerning both truth and memorialization initiatives, is central to this article. It foregrounds reception, and the complex processes required to facilitate reception.

One specific way of refocusing the debate on these questions related to truth-listening is through the lens of artistic practices as an approach to truth and memorialization. Throughout the world, in post-conflict or post-authoritarian settings, artists have developed practices that revolve around truth and memorialization and that have the potential to foreground thicker truths that go beyond forensic documentation (

Herremans and Destrooper 2022) In doing so, they problematize the ontological status of truth in debates over past violence and ongoing individual and societal harm (

Breslin 2017). As such, artistic interventions in the domain of truth and memorialization may resist dominant tropes, like that of the passive voiceless victim, the dichotomy between perpetratorhood and victimhood, the linear victim narrative, or the encapsulation of violence in a remote past (

Mihai 2018). By allowing for a variety of approaches to narration, and for multi-layeredness, complexity, and ambiguity, these artistic interventions touch upon questions about how truth practices can ‘presence’ difficult truths, as well as how these difficult truths are received. Artistic practices that operate in the domain of truth and memorialization could re-center the discussion about truth-telling and truth-listening and push it in new directions through their focus on asking questions rather than providing solid answers, the destabilization inherent in and required for artistic practices, and the requirement for audiences to be receptive (

Cohen 2020). Moreover, in the context of this article, artistic practices’ potential for resistance is also relevant in terms of the avenues they provide for resisting and counteracting the ongoing historical revisionism by foregrounding thicker understandings of truth that require authentic listening. The next section gives an overview of this history of violence and the responses to it.

3. Contextual Background: How Violent Legacies Have (Not) Been Dealt with

When the Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (EDSA) People Power Revolution overthrew the Marcos dictatorship in 1986, the incoming administration of Corazon Aquino had to deal with a legacy of massive direct as well as structural violence that took place during Marcos’ Marital Law. This legacy included high numbers of extrajudicial killings, torture and

salvagings,

2 illegal detention, and other gross violations of human rights, as well as large-scale fraud, corruption, and money laundering, along with institutional capture and cronyism (

Celoza 1998;

ICTJ 2021). Martial Law affected all Filipinos, but had particularly harsh effects in the Autonomous Region of Muslim Mindanao, a region historically inhabited by various Islamized ethnolinguistic groups collectively known as the Bangsamoro (

Lamchek and Radics 2021). The region had been disadvantaged compared to other parts of the Philippines since long before the Martial Law era. Under Marcos, however, the army significantly stepped up its violent repression and attacks in the region, and socio-economic and cultural injustices surged (

Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission 2016). This situation resulted in a protracted armed conflict between the Moro Islamic Liberation Front and the central government, which was formally concluded with a peace agreement in 2014.

Because of different timelines, nature of the violence, and political context, there are also great differences in the ways in which violent legacies related to Martial Law in general and those related to violence in Mindanao have been dealt with. Regarding the general legacy of Martial Law, the two most striking elements are the absence of formally designated truth mechanisms and the delay in large-scale memorialization initiatives.

To the extent that truth-seeking took place in the immediate post-Marcos period, it was part of the work of institutions like the Philippine National Historical Commission (a permanent body with no specific truth mandate), the Presidential Commission on Good Governance (that was mandated to locate and retrieve laundered money) (

Carranza 2008) or the Presidential Commission on Human Rights (which morphed into a standing Commission on Human Rights before concluding its report) (

Mendoza 2013), or of prosecutions of the Marcoses that took place in the US (

Davidson 2017), or, much later, the Supreme Court hearing regarding Marcos’ reburial on the Cemetery of Heroes and Martyrs (

Destrooper 2023). While carrying out important documentary work, none of these instances had the formal objectives of truth mechanisms, such as reconciliation, cementing state-sanctioned narratives about past violence, or reaching out to broad audiences. Hence, even if significant documentation about past violence and injustice exists, these facts do not always easily find their way into public discourse. An important example thereof is the multitude of affidavits submitted by victims in the US class action against Marcos, which never traveled back to the Philippines due to prohibitive procedures for access to these documents (

Ela 2017).

Memorialization received more attention from the start, both by state and non-state actors, but a boom in memorialization initiatives only materialized in the past decade. On the side of state actors, the so-called Reparations Law of 2012

3 sought to offer reparations to victims of the Marcos regime, both monetary (for which Marcos’ stolen assets would be used) as well as through the establishment of a memorial. A Human Rights Violations Victims’ Memorial Commission was established to construct a physical memorial, museum, and library to honor and memorialize victims of Martial Law. Interestingly, while the Commission was supposed to develop a physical space for memorialization, Congress’s refusal to release (available) funds until early 2023 meant that the Commission had to proceed through low-budget non-material initiatives for most of its existence. This resulted in creative and innovative approaches to memorialization that can exist in the absence of a physical space for memorialization, such as living libraries, talking circles based on oral history approaches, Wikipedia editathons, or TikTok battles.

This exploration of immaterial and non-place-based memorialization initiatives can also be observed on the side of civil society, where memorialization has a longer tradition. One of the main actors in the domain of memorialization,

Bantayog ng mga Bayani (Monument of Heroes), has been documenting stories of resistance and martyrs since before the fall of the dictatorship. It erected a Memorial Wall and documentation center in Manila, which it complemented with immaterial and non-place-based practices, albeit in more traditional forms, such as commemorative events. Recently, Bantayog staff joined forces with a younger generation of justice activists to set up an online museum to reach a broader audience. This younger generation of activists is an important driver behind the current boom in memorialization efforts. Their activism is typically inspired by the ongoing disinformation campaigns that seek to muddy historical facts and create a climate of uncertainty regarding Martial Law (also see

Wedeen 1999). As some activists indicated, they sometimes label their activism as memorialization rather than truth-telling in response to the contested connotation of the word ‘truth’ and the polarized societal debate, and as an attempt to reach audiences across societal divides. The choice for immaterial and non-place-based initiatives, too, was explained along similar lines by some interviewees: in a context of shrinking space for activism (notably since the presidency of Duterte) and resource scarcity, decentralized and immaterial approaches that can less easily be physically attacked have become more prominent.

4 As I will argue below, this pragmatic choice for immaterial approaches has had interesting consequences with regard to truth-listening.

A specific subset of civil society initiatives in the domain of truth and memorialization are those driven by artists, curators, and creative professionals. These include exhibitions by and in galleries (e.g., Ateneo Art Gallery), research projects with an artistic component (e.g., Weaving Women’s Words), projects by artistic collectives (e.g., Dakila), individual artists developing artistic practices around Martial Law violence (e.g., Kiri Dalena), and creative professionals engaging in the narrativization of existing documentation (e.g., the Storytellers). The prominence of these artistic practices further contributes to a memory landscape that is shaped by the interaction between material and immaterial, and place-based and non-place-based practices. In addition to being rooted in the broader ‘memory boom’, these artistic engagements can also partly be understood in light of the explicitly activist profile of some of the important art academies and universities.

5 Also, the 2014 Mindanao Peace Accords and the growing attention to violence there could be argued to have contributed to this memory activism—artistic and otherwise—by putting debates over memory and truth (including those related to Martial Law proper) higher on the agenda again.

As part of these peace accords, a Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission (TJRC) was established, which delivered its report in 2016. In addition to adopting a long-term perspective that assessed Martial Law-era violence in light of longer and deeper dynamics of direct and structural violence, the work of the TJRC underlined the importance of not only focusing on truth-seeking and truth-telling, but also listening: it organized several

listening sessions where victims could talk about their experience (

Transitional Justice and Reconciliation Commission 2016). Using this label implicitly shifts the focus from victims giving testimony toward related questions of what is needed for audiences to be able to listen to these stories. Because of institutional limitations and limited mandates, these questions were eventually left unanswered as the structure of the listening sessions remained fairly close to that of a typical truth-telling exercise. It is against this background that the Weaving Women’s Words project has sought to revisit this question of how to ‘presence’ complex and multilayered truths in ways that can meaningfully be received. This paper speaks to practitioners’, activists’, and professionals’ growing attention to how difficult truths can be heard, and seeks to enrich the conceptual underpinnings of this emerging debate, without seeking to be an impact study of how impactful their strategies are.

4. Case Study: Weaving Women’s Words on Wounds of War

The focus of the empirical section of this article is the ‘Weaving Women’s Words on Wounds of War’ project (WWWWW), which is the artistic component of the ‘Weaving Women’s Voices’ research project run by the Department of Political Science at Ateneo de Manila University, which seeks to further research, solidarity-building, knowledge-sharing, and training, and which presents itself as a memory project seeking to further transitional justice (

Weaving Women’s Voices 2022). The broader project is coordinated by Lourdes Veneración Rallonza, a former senior gender advisor at the TJRC who was involved in the development of its listening sessions. It starts from the acknowledgment that there has been limited societal awareness about the experiences of women who faced massive direct and structural violence (personally and as members of specific communities) and about the impunity for that violence.

6 The project, therefore, approaches participating women as bearers of knowledge and co-authors of the emerging narratives, arguing that ‘it is important to document those narratives because in the Philippines, we still do not have that kind of formal process or mechanism’.

7Because of the acknowledgment that the experiences of these women (who come from six different sites in the Philippines, including Bangsamoro) do not lend themselves to ‘easy storytelling’, and that ‘theirs are not stories that translate in straightforward ways from raw experiences to narrative form,

8 the research component was complemented with an artistic project. This component starts from an exploration of the limitations of different kinds of documentation, the difficulty of navigating vast amounts of documentation, the ‘diminished gaze’ of mainstream media, and deeply rooted prejudices against women, indigenous groups, and Islamic cultures (

Castro 2023). The creation of spaces for articulating lived violence in new ways therefore became a crucial ambition, addressed through the WWWWW project that constituted a space where narratives of violence are constructed and circulated through visual artefacts and interventions (Ibid.). This approach illustrates the vital role of artistic practices in the pursuit of justice, truth, and memory, as well as the importance of curatorial practices for the dynamics of truth-listening. Because of this article’s focus on truth-listening, the curatorial approach that has been put in place to achieve this aim constitutes the focus of this empirical section.

9The WWWWW exhibition encompassed a physical show as well as an online virtual exhibition, both developed by the participating women who collaborated with an artwork developer and a curator, seeking to move beyond traditional representations of violence.

10 Starting from this position, the curatorial team developed a practice that revolved around the recovery, reconstruction, and problematization of images to create new

lieux de mémoire, as well as around artistic and traditional practices’ broader potential in terms of accounting for complex forms of violence (

Castro 2023). This approach steered the interventions in each of the six localities, which constituted the organizing principle for the exhibition. Throughout the exhibition, material and immaterial interventions interacted. A majority of the material artworks consisted of or included narratives expressed through weaving and textiles. These textiles were considered to have multiple meanings and effects, from highlighting the rich textile tradition and the role of women therein, to the risk of locking women up in more stereotypical roles and the need to deconstruct these stereotypes through careful curation of the artworks.

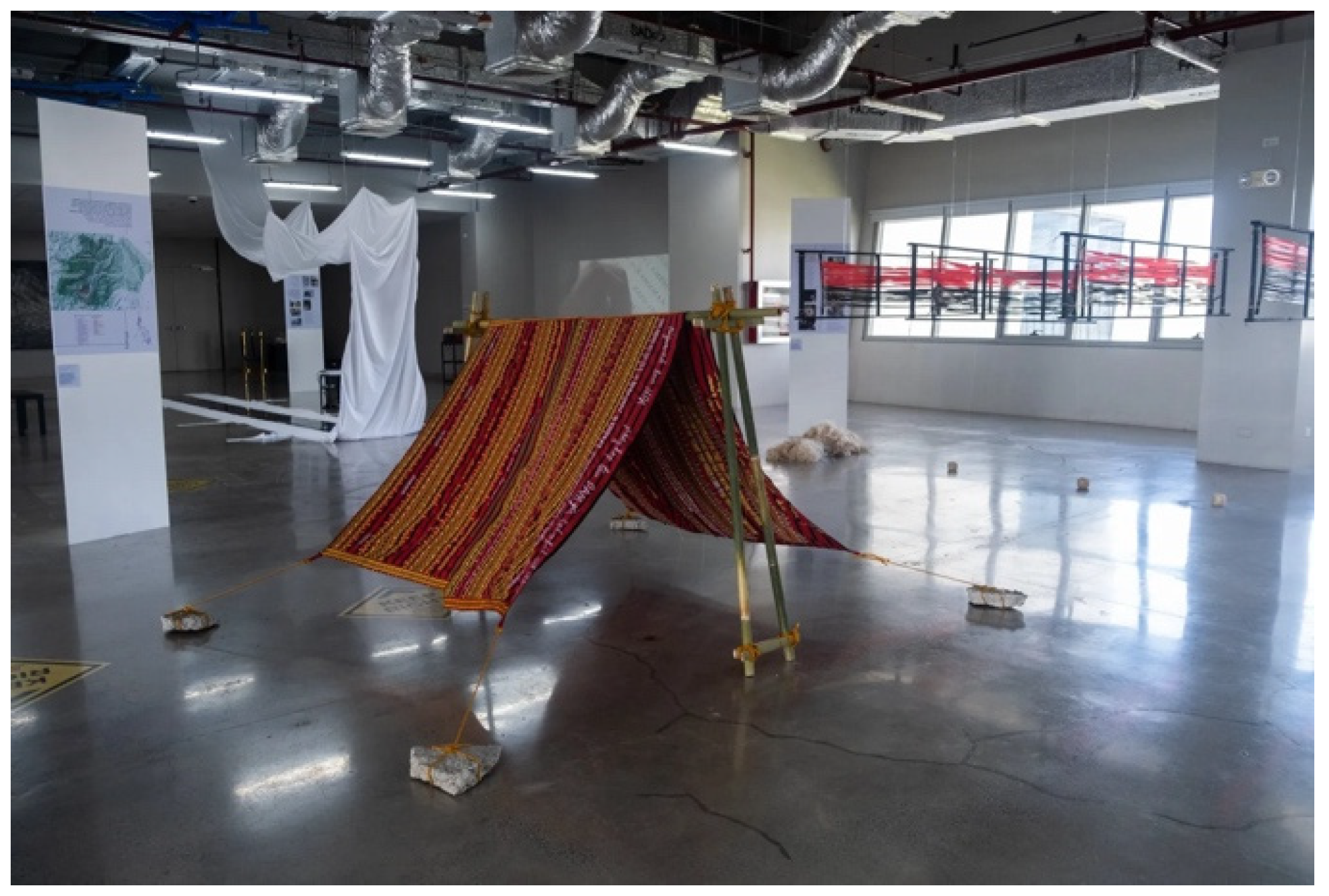

11For the installation reflecting the first site (see

Figure 1), the notion of tenacity was used as a central organizing principle. This installation included autobiographical recollection, backstrap weaving, embroidery, annotated maps, and a video installation. It combined narrative forms (such as excerpts from autobiographies) with visual prompts (such as maps capturing geographies of resistance in the Cordilleras region) and artistic and artisan interventions (such as hand-woven wrap-around

kalinga skirts), highlighting the inter-temporal nature of both the violence and the resistance to it.

The concept of grace structured the second installation (see

Figure 2), which included an autobiographical recollection, an impression on cornstarch, annotated maps, and an installation of plain-woven polychromatic prayer mats. These works explored the tension between women’s aspirations and pressures emerging from modernization, Christianity, and fundamentalist strands of Islam. The mats woven by the Samalan women sought to capture grace and ephemerality within the material of the work, of which the molds will disappear soon to reveal new—or pre-existing—realities (

Weaving Women’s Voices 2022). The justice, truth, and memorialization called for in this installation is one that acknowledges Sama and Tausug ritual life, counters invisibilization, and guarantees their survival and flourishing.

The installation reflecting the third locality foregrounded the concept of discretion, and comprised autobiographical recollection, annotated maps, impressions on cornstarch, and a video installation (see

Figure 3). It represented the innovations in social order and the active role of women weavers, dyers, and embroiderers in leading their communities into a cash economy by selling their works. For this specific site, considerations about what women did (not) want to become public knowledge about their histories of violence and resistance were central. For this specific intervention, considerations about what women did (not) want to become public knowledge about their histories of violence and resistance were central. This led to complex questions about the right of the nation to know and the agency of the victim to choose whether they want to speak or stay silent, which in turn posed its own complexities because individuals were often inclined to speak about their suffering but also experienced a reticence to do so. This led the curatorial team to explore the technique of Ikat, which is part of T’boli culture. Ikat is a system of reserve dyeing whereby parts of the threads or the cloth are treated with a product that resists dye, meaning that once the thread is dyed, parts of it are covered and others remain visible, so that the story ‘is there, but it’s not there’ (

Weaving Women’s Voices 2022). The artwork consists of reproductions of

ikat warping frames for dyeing with printed text.

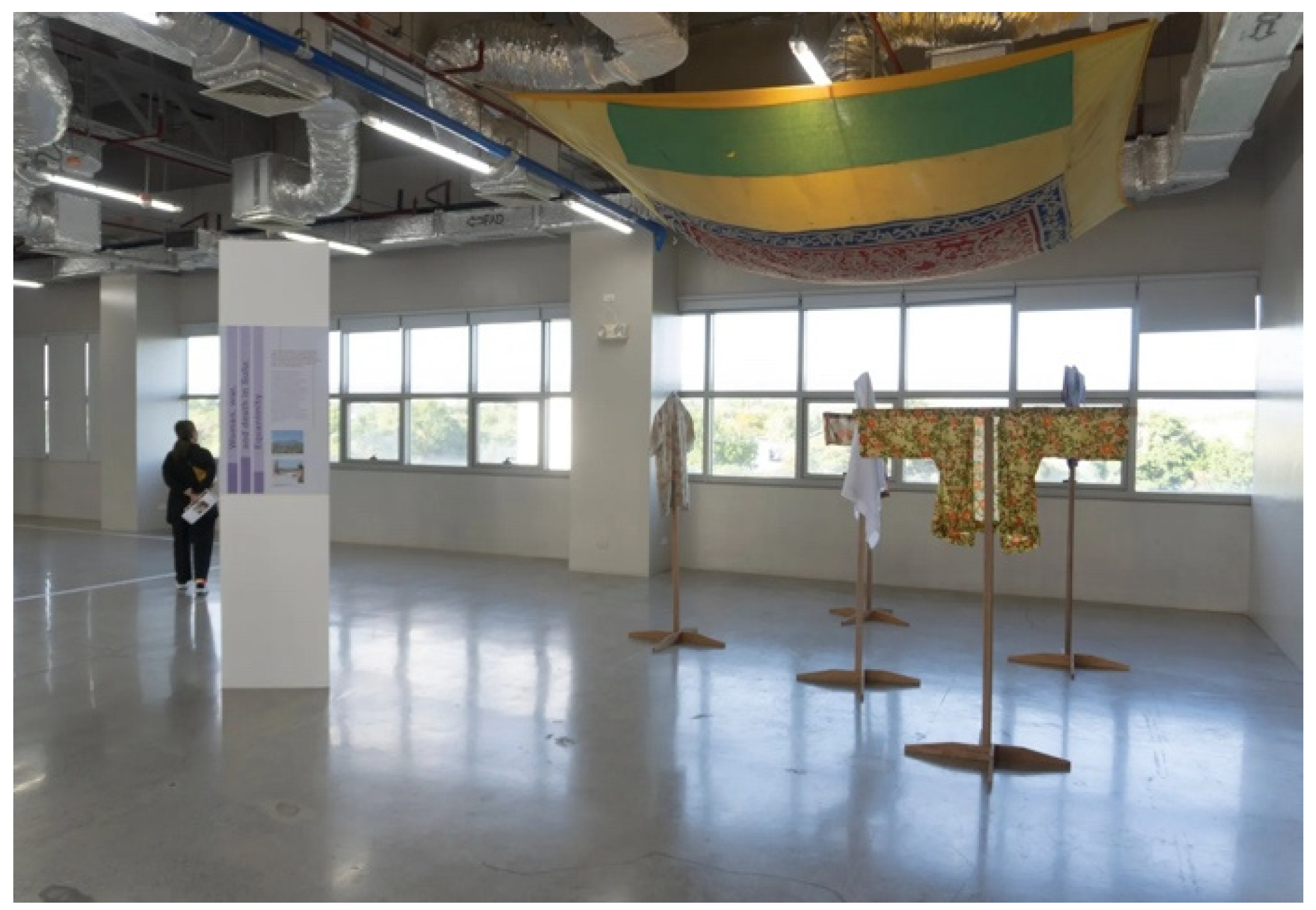

Equanimity was the concept structuring the installation for the fourth site, which included autobiographical recollection, embroidery on garments, annotated maps, woodworking, and an installation of a traditional Tausug appliqued canopy

(luhul) (see

Figure 4). This installation reflected on the loss, reconfiguration, and recreation of identities women faced when joining armed groups. For the installation, women donated a uniform they used at the time of war, which they embroidered with their names, to tell stories that ought to be understood as a form of memorialization as much as an ongoing reality of negotiating identities.

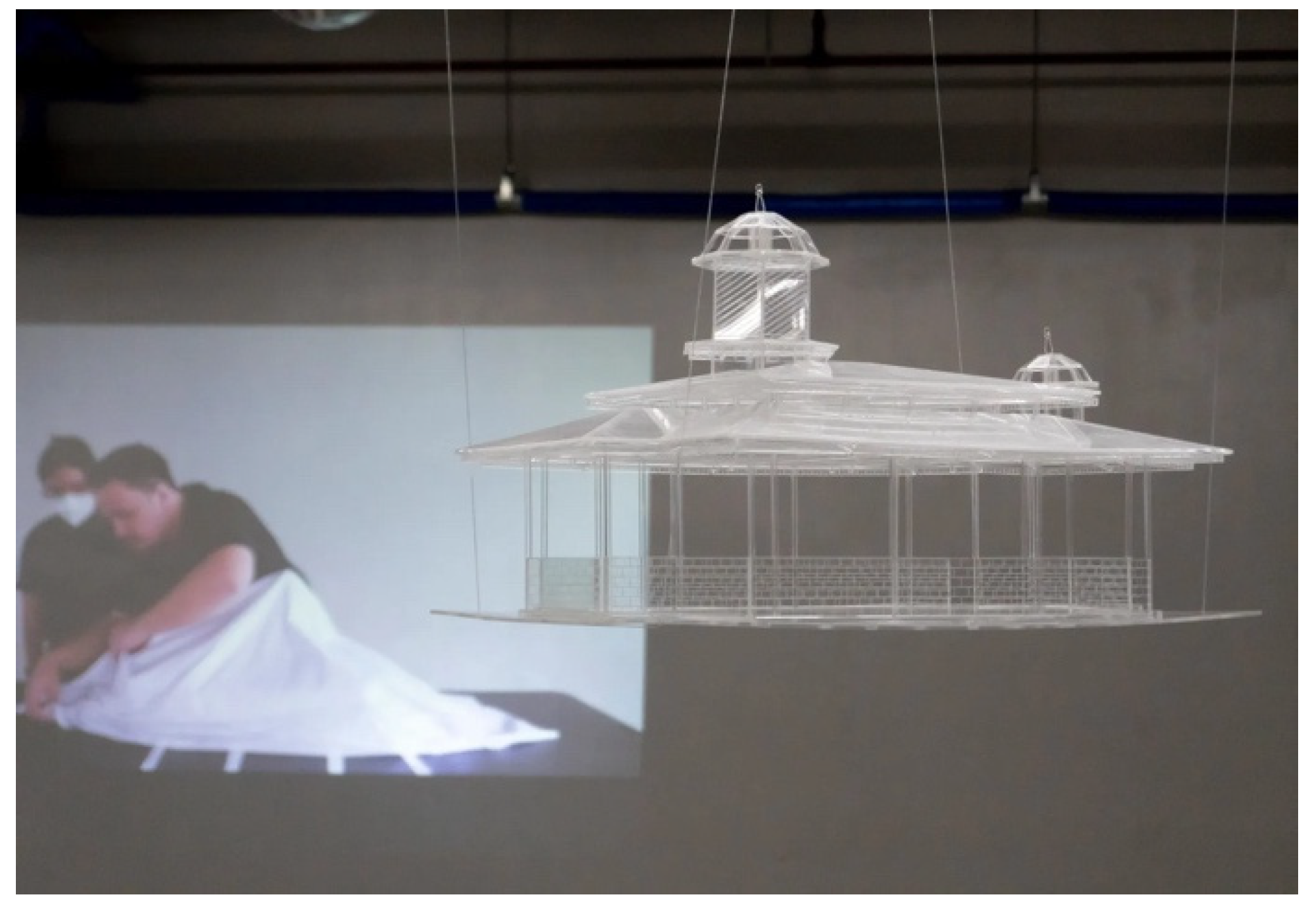

For the fifth site, narratives were organized around the concept of endurance (see

Figure 5). An installation consisting of an autobiographical recollection, masonry, sandblasted engraving on stone, videography, photographs, annotated maps, and a digital architectural rendering entered into dialogue with a place-based mass grave marker near the Taqbil Mosque in Palimbang where victims of the 1974 Malisbong massacre are buried and remembered. The non-place-based intervention complements the preference of residents for a form of memorialization and truth-telling that revolves around the actual mosque which still carries the marks of gunshots and blood (

Weaving Women’s Voices 2022). The exhibition features a video installation documenting the design and fabrication of a physical memorial that is currently portable, but that may be permanently installed in the Taqbil Mosque in due course. This way of proceeding allows for the mobility of this memorialization material, as well as integration into more permanent structures.

A sixth and last installation, revolving around the notion of amplification, contained autobiographical recollection, digital architectural renderings, acrylic and wood architectural modeling, annotated maps, embroidery, and an installation (see

Figure 6). The artwork dealt with past and ongoing military action in the region and underlined the fear of repetition created by the blind spot in the national imagination about past massacres brought on by the

Ilagâ. At the same time, the artwork also questioned the dynamics of memory and the truthfulness of remembering (see below).

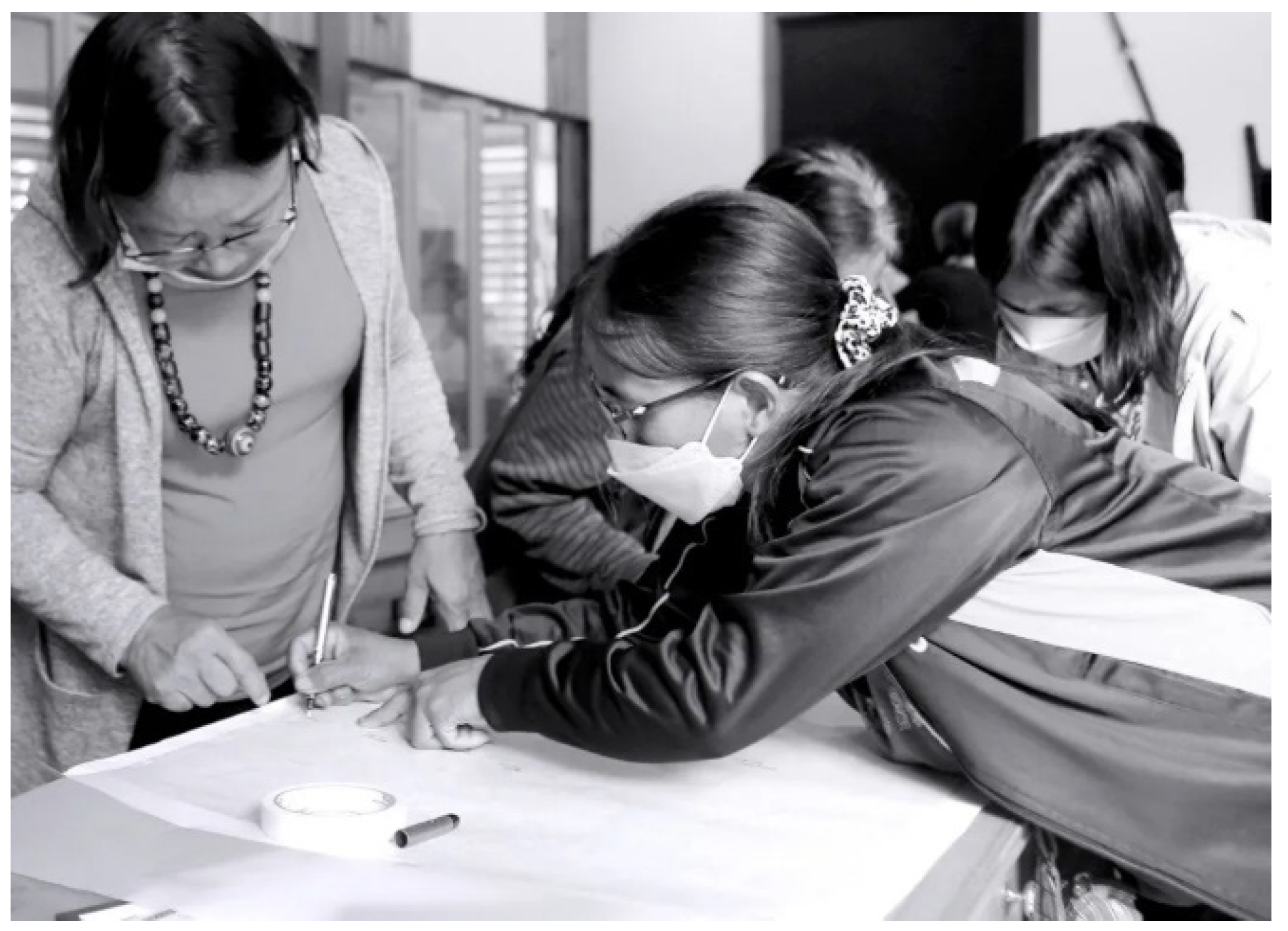

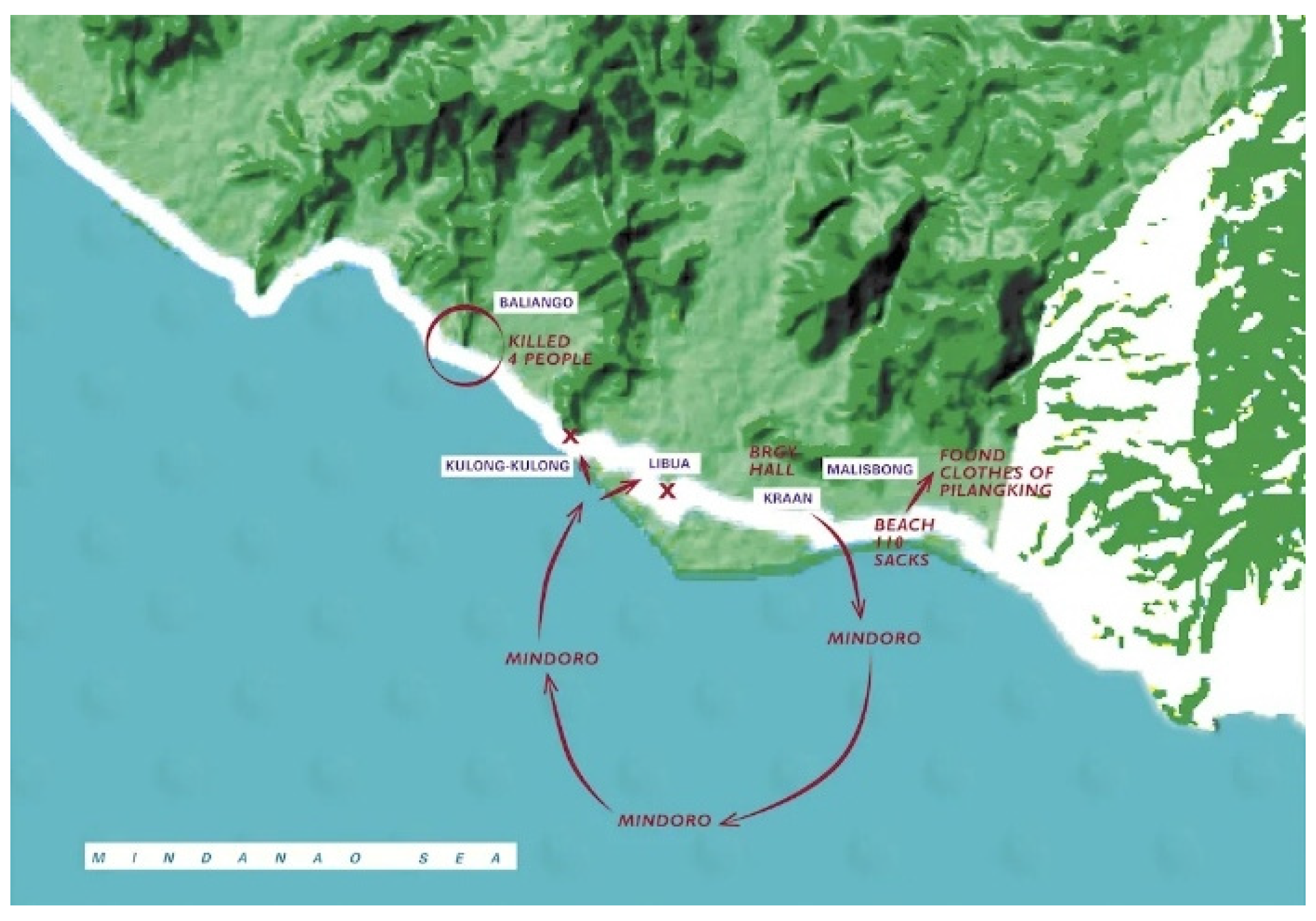

Throughout, maps and the practice of mapping played a crucial role in defining the memorial practice and installation. With each of the six groups of women, the team first engaged in a geographical mapping of stories, to make visible experiences in ways that are not linear or narrative, per se, but that follow a place-based logic (see

Figure 7). In doing so, the narratives, memories, and memorial practices emerging throughout the process have an inherent place-based dimension to them, even if some final outcomes, like the online museum, are entirely untethered from the places and spaces in which these stories emerged. Maps were used to detail the locations of activities of participants in combat, to identify relevant and constitutive spaces in women’s lives, to overlay individual and personal maps with collective trajectories and geographies, or to bring that which was invisible because it happened in remote spaces back into the conversation. An example of the latter is Map 5 which shows the trajectory of the Mindoro ship (see

Figure 8). Most narratives of violence regarding the Palimbang massacre focus on the killing of men in the Taqbil Mosque. Simultaneously, however, women and children were taken to a naval landing ship, the Mindoro, for weeks, where they experienced rape, forced marriages, hunger, psychological violence, and torture. Their remoteness at sea rendered this violence invisible. Starting from a mapping exercise, facilitators sought to counter this invisibilization. Also, other mapping exercises offered non-verbal tools to present a personal or collective experience as part of a broader dynamic of place-based and cultural violence. While facilitators started from place-based approaches, they also moved beyond these to avoid the entrapment of stories, experiences, and narrators in frameworks typically associated with these place-based practices, and to propose new interpretations, formulations, and ways of imagining. This interaction between place-based and non-place-based approaches could be observed in the process as well as the outcome, where, for example, several installations could be read as stand-alone non-place-based interventions, as well as being components of a greater place-based memorial structure. This combination of place-based and non-place-based approaches to memorialization and ‘presencing’ sought to reflect layers and complexity that otherwise risk being overlooked.