Abstract

Confusion over what constitutes appropriate childrearing practices in culturally diverse settings may result in the stigmatization of ethnic minority families and over-reporting to child welfare services. This study explored stakeholders’ views on (in)adequate supervision across cultural and socioeconomic groups and how they assess the risk of harm in cases of lack of supervision. Focus group discussions were held with (a) adult caregivers (n = 39) and adolescents (n = 63) in family-based care from French-speaking Quebecers and migrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, and South Asia; and (b) professionals (n = 67) in the education, health, child welfare, and security sectors in Quebec. The main criteria used to assess the appropriateness of supervision were the maturity, level of ability, age, and sex of the child, as well as contextual factors, such as proximity of other people, location, and type and duration of the activity. Mobility and immobility notions are used to explore the developmental considerations of competence and readiness within the home and in other social environments where adults’ and children’s perceptions of safety and maturity may differ, as well as the need to move away from rigid policy implementation. This paper advocates for careful consideration of the capacity and agency of children affected by migration in the provision of childcare support and their meaningful participation in research and decision making in matters that affect them.

1. Introduction

Transnational human migration shapes social relations and child rearing beliefs and practices, which in turn are context- and culture-bound. The way in which parents care/supervise depends largely on their own abilities, on each child’s mobility across developmental standpoints (physical, cognitive, emotional, and social), on cultural/local norms/expectations of children’s contributions to their families, and on conditions of the surrounding environment (Weisner 2005). Moreover, as individuals move from their country or community of origin to transit or receiving societies, family dynamics and roles often change, including and who supervises the children and how they do it. These changes can apply to newcomers, as well as to local residents and 2nd and 3rd generation migrants in culturally diverse societies over time. Cross-cultural mobility is often compounded by socio-economic mobility (e.g., due to the type of employment offered to newcomers and reduced support networks) (Putnam 2007), barriers to access services (e.g., due to language skills or lack of familiarity with available resources) (Paat 2013; Yu et al. 2005), and local norms about the “right” methods of raising children. All these circumstances influence parenting behaviors and how parents interact with and are perceived by other members of the community. For instance, there is evidence that some migrant children who spend time home alone while their parents work do so in fear of being reported by their neighbors to the authorities (Klassen et al. 2022). In fact, community members and professionals who interact with parents and children in a range of environments—from schools to clinics—are the main sources of reporting to youth protection in Canada (Hélie et al. 2012). Research has documented that many youth protection professionals consider the parenting practices of immigrants to be less adequate than those of mainstream parents (Chand and Thoburn 2005; Sawrikar and Katz 2014). The extent to which professional assessments consider cross-cultural mobility and families’ views in the determination of what constitutes adequate child supervision by family-serving professionals is unclear. Our study aimed to address this gap.

Accounts of exclusion of migrants and young people’s perspectives are well documented. In the field of child protection, scholars and practitioners have denounced the politics of power, racial discrimination, and insufficient understanding of the predicament of migrants and their influence on childcare practices (Lavergne et al. 2008; Sawrikar and Katz 2014). In culturally diverse societies with a large immigration stock, such as the USA and Canada (UN 2020), these challenges have resulted in stigmatization and overreporting of migrant and racialized families to youth protection (Hassan et al. 2011; Putnam-Hornstein et al. 2013). They have also led to a misunderstanding of how child agency or ‘the intrinsic capacity for intentional behavior within an individual’s environment(s)’ (Thompson et al. 2019, p. 239) is practiced and performed in the context of migration. This contrasts with growing recognition of children as social agents, with capacity to make valuable contribution to their families and communities (Katz 2015). Beyond the need to respect human rights (UNGA 1989), the benefits of strengthening child agency extend to a child’s own wellbeing (González et al. 2015; Gurdal et al. 2016) and protection (Lansdown 2020).

Researchers have paid little attention to how power relationships and cultural bias are played out in the assessment of child supervision practices that differ from those of the mainstream receiving society. Moreover, the perspectives of children and even parents are often missing. These gaps in the scholarly literature are of particular relevance in contexts with increasing immigration and cultural diversity, such as the province of Quebec, where almost 60% of Canada’s asylum seekers live and where international migration has recently driven strong population growth (Institut de la Statistique du Québec 2023). The exclusion of young people from having their voices heard in matters that affect them and the lack of cultural awareness on the part of family-serving professionals can lead to personal interpretations and (un)conscious biases that may result in inadequate service provision and unnecessary parent-child separation (Hafford 2010; Korbin 2002). Overall, a better understanding of the circumstances surrounding migrant families and how cross-cultural mobility influences their child supervision practices can contribute to strengthening community relations in culturally diverse settings (Klassen et al. 2022).

Using data from Geographies of Care, a multisite study about child supervision in cultural context in Quebec, this paper has a twofold objective: first, to contrast key actors’ understandings of what constitutes (in)adequate supervision in a culturally diverse society; and second, to showcase how cross-cultural mobility and child agency [can] shape caregiving and professional practice, including professionals’ assessments of the appropriateness of care (Grégoire-Labrecque et al. 2020). Children, adult caregivers, and professionals’ general views of adequacy of care are presented first, followed by participant-identified criteria used to assess the appropriateness of care at the level of individuals (caregivers and children), along with specific context. The findings are discussed considering previous research, and implications are drawn for future research, policy, and practice.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Setting and Sample

In order to take into consideration factors related to poverty and accessibility to support services, both of which have been linked to neglect, particularly among ethnic minority children (Jonson-Reid et al. 2013; Proctor and Dubowitz 2014; Schumacher et al. 2001), participants were sampled from diverse cultural and socio-economic backgrounds within two urban/suburban settings in Quebec province with both a high and low proportion of migrants (23.4% in Montréal vs. 3.2% in Trois-Rivières-Central Quebec) (Arora 2019).

A group of 169 people participated in the study (Table 1). A total of 39 adult caregivers and 63 children aged 12–17 years in family-based care from mainstream Quebecers (Francophone, Fr), and first- and second-generation migrants from the Afro-Caribbean/Black (ACC), South-Asian (SAC), and Latin American (LAC) communities participated in 13 focus groups (FG). Similarly, 10 FG were conducted with 67 service providers working with ethno-culturally diverse families in Quebec, including: (a) teachers and principals, (b) family doctors, pediatricians, and nurses, (c) police personnel, and (d) front-line child protection workers and supervisors. These categories of professionals refer two out of three cases brought to the attention of child welfare authorities in Quebec (Hélie et al. 2012). Participants were recruited via school boards, health and social services centers, community organizations working with culturally diverse families, youth centers, and the police. The project advisory committee included representatives from these sectors; it facilitated recruitment and contributed to the contextual appropriateness of the study.

Table 1.

Participants in the focus groups.

2.2. Materials and Procedures

Overall, 23 FG were conducted separately with adults and children in family-based care, as well as service providers. FG were selected to allow us to explore a range of perspectives through interactions between participants, including regarding this potentially sensitive issue (Jordan et al. 2007). FG lasted approximately 1.5 h and took place in the researchers’ or participants’ offices (e.g., schools or clinics) or in local community centers. They were conducted in English, French, or Spanish by a moderator and an assistant moderator/notetaker using a structured interview protocol.

After providing informed consent, adults and children in family-based care were asked about (a) current and customary child caregiving beliefs and practices within families and communities, and the role of the state, including changes in recent history in the provision of care; (b) the main challenges that families encounter in caring for children; and (c) the meaning and consequences of this situation for children and families. FG with community leaders and service providers working with children and families explored their experiences related to lack of supervision of children and support (determinants, consequences), and the criteria and threshold they use in assessing/substantiating (risk of) harm and identifying signs of safety and support in the context of different socio-cultural norms. Towards the end of the FG, participants were presented with four case vignettes (V) (Table 2) and asked whether they represented appropriate care/supervision or not and why, as well as whether the family needed any help, and if so, and what type. These vignettes, likely to generate a range of perspectives, were developed with initial input from diverse caregivers and children. Probes throughout the FG explored the role of different family members and variations across child sex, age, ethnicity, and level of ability.

Table 2.

Child supervision vignettes or scenarios used in focus groups.

2.3. Data Analysis

All FG were digitally recorded with the consent of participants, transcribed verbatim, and denominalized for analysis in N-Vivo 11 (Lumivero 2015). Notes taken during the FG, along with participants’ demographic information, were also included in the analysis (Barbour 2014). First, all transcripts and notes were read by two researchers to identify themes from the interview protocol, as well as others that emerged from the discussions, and a preliminary codebook was created (Corbin and Strauss 2008). Then, two researchers applied this codebook to two transcripts, and coding discrepancies were solved through discussion with the first author. Then, the codebook was refined through iterative coding and applied to all transcripts. Results were analyzed for each focus group and then compared across all groups (i.e., professionals, caregivers, and children) to construct cross-cultural typologies of (in)adequate supervision and support, as well as risk assessment approaches (Krueger and Cassey 2015). Attention was paid to other factors which may influence FG results, such as setting and social interactions (Green and Hart 1999; Halkier 2010), developmental level (age/maturity) of the child (Barbour 2014), and disconfirming comments which challenged emergent explanations of patterns in the data (Barbour 2005). Finally, criteria used for assessing adequacy of supervision were grouped according to themes, and mention counts were recorded in Excel by participant group and vignette; a heat map was developed to graphically represent results. Trustworthiness was ensured through verbatim transcription, team coding, audit trail by means of a detailed codebook, and reflexive notes to document observed patterns and decisions made, as well as the use of direct quotes to illustrate the themes (Guest et al. 2012). Preliminary findings were shared with the advisory committee (AC) and local partners, and their input was recorded towards interpretation. All quotes have been translated into English for inclusion in this manuscript.

2.4. Ethics

The study received ethics approval from McGill University’s Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences and the Integrated Health and Social Services University Network for West-Central Montreal. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and parents/guardians of children younger than 14 years. Special attention was focused on facilitating interviews in a nonjudgmental way and creating culturally safe spaces for communities to participate. There were no incentives for participating; transportation costs were covered, and refreshments were provided to all participants.

3. Results

3.1. General Assessment of Appropriateness of Care by Vignette and Respondent Group

Focus group facilitators read each vignette aloud in turn, followed by the questions described in the methods section. Almost consistently, participants would begin requesting clarifications, indicating that there was not enough information in the vignette to make an assessment. In most cases, however, the initial “it depends” did not prevent participants from concluding whether the scenario described revealed appropriate care or not (Figure 1). Thus, overall, there seemed to be general agreement among professionals regarding the appropriateness of care described, particularly in Va (7-year-old with grandparent), Vc (7- and 9-year-old walking back from school and staying home alone), and Vd (15-year-old girl out until 11 p.m.). The latter was, however, deemed clearly inadequate by one group of police personnel and one group of healthcare professionals.

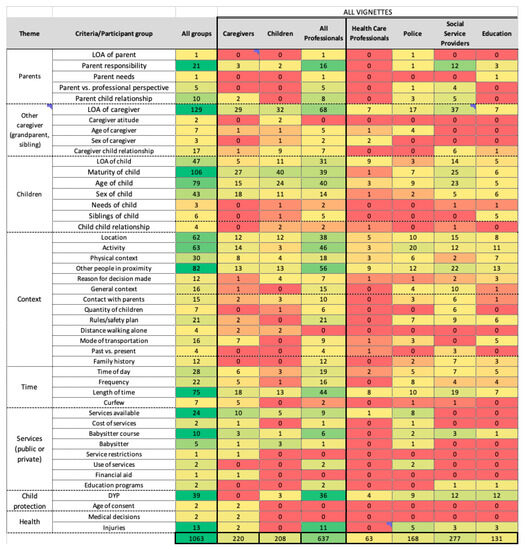

Figure 1.

Aggregate of criteria volunteered by participant group across four scenarios. Note: colors indicate frequency of mentions ranging from dark green (more mentions) to solid red (no mentions).

Opinions seemed more divided among caregivers and children. Only situations described in Vb and Vc were deemed (mostly) to portray inadequate care by half (Vb) and 40% (Vc) each in regards to caregivers’ and children’s groups, respectively, while some groups reached no agreement. Oftentimes, French Quebecer caregivers assessed situations as inadequate when migrant groups did not. This was particularly salient for vignettes (b) and (c). Vb seemed to be the most controversial among both families and professionals and was largely assessed as inadequate care by the former, as well as by 3 out of 11 professional groups (with another two reaching no agreement).

Some differences were noted among children from different cultural groups (e.g., Vc was considered adequate by ACC and Fr, but considered inadequate by SAC, with consistency of opinion within cultural groups), and between caregivers and children (within cultural groups) (e.g., Vd among Fr caregivers and children and Va among ACC caregivers and children).

3.2. Criteria Created by Respondent Groups to Assess Appropriate Care

3.2.1. Overall Themes/Factors Identified by Participants

Criteria spontaneously identified by caregivers, children, and professionals to assess appropriate care are listed on Figure 1. These can be grouped as referring to parents and other caregivers in the scenario (e.g., grandparents or older siblings), children, context, or environmental conditions such as location and time, existing programs (e.g., childcare services) and policies (e.g., child protection regulations), and health concerns. Not all factors were raised (or pertinent) in the discussion of all vignettes, yet at least one factor in each of those groups was spontaneously mentioned for all vignettes.

Across all groups and scenarios, the main criteria used to assess appropriateness of care pertained to (a) caregiver level of ability; (b) maturity, age, level of ability, and sex of the child; and (c) contextual factors, such as whether there were other people nearby, location, and type and duration of the activity (Figure 1). The role of the Directorate of Youth Protection (DYP) was also often mentioned by professionals and some children (not caregivers). Caregiver level of ability stood out as a key criterion identified by all participant groups. Adults and children alike highlighted the importance of knowing whether the caregiver can care for him/herself (e.g., able to run out of the house in the case of fire) as well as children: “What is limited mobility? It depends (…) in a wheelchair, blind?” and, “if he [elder] is able to speak and the child can cook for him to eat” (police). In regards to the same vignette, Va, children explained the challenge as follows:

“Yeah it’s a problem because, well if they sit down and they can’t get up, what if the kid is playing around with a lighter and a can of hairspray, I know that’s a bad child, but … What if they were playing around with those kinds of things and you set yourself on fire. You’re going to take forever to stand up and come at you and put you out. Or reach the phone.”(ACC)

“The kid can have too much energy and the grandparents can’t keep up with them.”(ACC)

“If the kid goes out of the house, they won’t be able to chase him.”(SAC)

“The old grandfather is not the one taking care of the child but rather the child taking care of the grandfather. That depends on the grandfather’s health state.”(LAC)

Some caregiver presented the limited mobility of the grandparent in this scenario as a potential opportunity for the elder to bond with the child: “He is not immobile, he is not lying in a bed, it is a reduced mobility so it is a moment of intimacy between them to share” (Fr).

In the case of the 10-year-old girl looking after her younger siblings, participants questioned the maturity and autonomy/independence of the girl and considered it may be too much responsibility for the child, particularly if the younger siblings have special needs or the child had not taken the babysitting training. Children, for example, were concerned that:

“There is a lot; there can be unexpected accidents at home and the girl will not be able to handle the situation alone and far less with the other two children.”(LAC)

Professionals, however, raised concerns related to the looked-after children and identified several contextual factors that would need to be considered, along with the level of ability of the caregiving child:

“5 AND 3 YEARS, OH MY GOD”(Health Care)

“A 3-year-old child is easier for a 10-year-old to take care of. It’s the 5-year-old who will sometimes be in opposition or will decide to do things that the other has trouble telling him ‘no, you can’t do that’”(Education)

“If I had a 10-year old daughter, like super responsible and I’m not far away, and I have my cellphone, I’d feel okay with that.”(Police)

Maturity, age, level of ability, and sex of the child were also regularly considered when assessing the appropriateness of care. In vignette (a), if the child was calm, obedient, autonomous (e.g., could walk, eat, and go to the toilet by herself), did not have behavioral issues, and was well educated, then it may not a problem to leave the child with an elderly grandparent:

“If it’s a calm kid, like listen to what the grandparent says, like if the grandparent says to sit here and stay calm, if the kid listens and everything, I think that, I don’t think it’s a problem.”(Child SAC)

“I feel that the boy might be like very energetic, compared to the girl who might like calm down if you give her toys and like let her play. The boy might want to play outside more, like I want to go play soccer, or I want to go to the park. [inaudible], okay here’s a doll. It’s savage.”(Child SAC)

“What if something happens to the grandparents, the child won’t know what to do. If the grandparent had a heart attack or something like that, the child won’t know like what to do with him. He won’t know like to call; he won’t have the sudden reflexes to call 911.”(Child SAC)

The interaction with the previous criterion, however, was also raised. For example:

“To have old people in my family, it means that when you get up from the toilet, you have a hard time getting up. It means that if you get into the bath, you are no longer able to get out. So, a 7-year-old can’t do that because their spine isn’t made to support a heavy person.”(Police)

The personal characteristics of children in Vc and Vd were also evaluated, as well as the interaction between the children in scenario (Vc) (e.g., “it’s two boys and they might fight” SAC children [and police]).

“At this age [9 and 7 years of age] you can do silly things for two hours.”(Fr Caregivers)

“If they are able to come home from school on their own, they are able to take care of themselves.”(Fr Children)

“At that age, they’re not that responsible enough to do their homework and take care of each other.”(SAC Children)

“I feel that a 9-year-old would be able to manage.”(SAC Children)

The children’s own confidence and comfort levels regarding being left unsupervised must also be considered:

“It depends on the child; it depends on their sense of personal security in relation to that. If the children feel comfortable in that space, they don’t see any problems. The routine is clear, no one is afraid, everyone feels safe. Parents are not worried, it’s okay.”(Education)

Children deferred to parents for assessing children’s ability to stay on their own:

Parents know their children and if they are ready to be left alone. Like at 7 years old I think their mother will know how, mother or father, they will know how their child acts, how they will react.

I2: then it depends on the child not to …

P3: but it depends if the mother leaves them or not, if she said it’s ok it’s ok. I think she knows”(SAC children)

The children described nuanced and reciprocal roles between parents and children in preparing them for self-direction and the responsibility involved in the supervision of themselves and their siblings. When asked how children are raised in their communities, three 15-year-olds, all from Latin American communities, responded as follows:

“… mothers are the ones who take care of the care and feeding, who are responsible for the things of children, young people, and adults. How we organize our room, wash our clothes, do homework at a certain time, play, go with friends outside … have a balanced schedule.”(P2)

Gendered socialization and context, including perceptions of the safety of the neighborhood, were also included in the youths’ descriptions of their preparation.

“… being a girl, they are more capable of being calm than a boy because they are more responsible because from a young age, they are taught things …”(P2)

Caregivers also highlighted the role of parents in preparing children to be unsupervised:

“At a certain point you have to look at the level of responsibility of your child to allow you to move forward and evolve; otherwise, we wait, and she is 16 years old, and I say to myself ‘I should have [addressed the issue] before”(Fr Caregivers)

Several professionals agreed that parents are best positioned to assess children’s ability to care for themselves. For example:

“We can try to see with the parents if they consider that their children are mature enough, but I find that a bit young.”(Police)

“P3: Me, my children, they are at 11 and 9 years old, but that was it. They are all alone and they come to have lunch alone, they call me when they arrive. They eat their plate. They leave. They call me back afterwards. In the evening, when they get home from school, they call me, they do their homework and they ask each other their vocabulary words, and their sheets are there. I arrive and it works. They have great good grades … so I don’t need any help We know our children; we brought them up a certain way.

P5: We know our children.”(Police)

Nonetheless, some professionals considered that the abilities of children aged 7 and 9 years were not to be relied upon:

“Can a child be trusted? He’s a child. Does he have reasoning ability, analytical ability? No, he doesn’t. You can’t stay there even if it’s a responsible child. You have to take it for granted that maybe he will want to challenge and try … something new! Fire—he knows he’s not allowed to play with it, but we’ll try to light the candle. It’s going to be cool. It’s gonna be beautiful.”(Police)

The risk to overprotect children was also raised by some professionals:

“We find it appalling, a 13-year-old girl cannot be left alone, but we infantilize them, we protect them, but perhaps if the children are well equipped and the parent has no choice because he works, he maybe they need to be equipped or I don’t know …”(Health Care)

Even if girls were said to mature earlier, in general, caregivers and professionals held the same opinion for adolescent girls and boys going out at night.

Contextual factors most often mentioned included proximity of other people, location, and type and duration of the activity. The proximity of family, friends or neighbors who can assist with childcare, or at least serve as a resource for children in an emergency, was mentioned by all participating groups. In the words of an educator, “Is there an adult ready to intervene if ever something comes up?” (Vd)

“Sometimes there is a neighbour that they just go knocking across the hall, I’m okay with that, you know?”(Social Services)

“P: Not necessarily services but ask a friend, a neighbor, a grandmother to come as I’m going to do my grocery shopping can you just come.”

“The community, if you make friends here”(Fr Caregivers)

“She [mother] raised us to know the neighbour’s numbers (…) Especially if it’s an emergency”(ACC Children)

“I would have a plan with the neighbors to be sure that if something happens, they have the resources and that there is at least one helper who looks after the house.”(Police)

“In a small Native community where everybody knows each other, like I would allow it.”(Police, Vd)

In the case of Vd, knowing who the adolescent is with (i.e., one or more people? older than or same age as her? Boyfriend or girlfriend?), and whether there are parents around was important for adults.

“- As a parent you will assess who the boy is. If you find out that she’s coming back with a boy and you don’t know him, I think you’re going to have a chat with your daughter.

- It’s a friend anyway. Whether it’s a girl’s friend, it’s the same principle. Who is she going with? You need to make sure you know who she is with.”(Social Services, Vd)

Living arrangements (e.g., apartment vs. detached house), place of residence (e.g., rural vs. urban), and surrounding spaces (e.g., where adolescents gather (Vd), or the environment which the children need to walk through on their way back from school (Vc)) were mentioned by participants. For example, children described aspects of location to justify the appropriateness of some care arrangements:

“I used to go to the park. I knew exactly where I was, or I go to my neighbor’s house”(ACC Children, Vc)

“It depends on the neighborhood. Like if it’s like very, if there are a lot of houses close by and the neighbors are, like you know the neighbors are good, I guess you can leave them at home. I know my cousins like, two of my cousins stayed home at a really young age after school. And like they were fine. It’s because they live in a really close neighborhood.”(SAC Children, Vc)

Knowing where children are and what they are doing was important for caregivers and professionals:

“It depends on the activity, it depends where.”(Education, Vd)

“Do they go somewhere by the side of the road or in a bar downtown.”(Education)

“P2: It’s sure that they were … where?, at the IGA [supermarket] or at the disco …

P4: At the convenience store, downtown, St-Michel …”(Police)

“P2: It’s more about knowing what she’s doing until 11 p.m., is she in the park with I don’t know who? Or?”

“P1: there is a difference between being at Émile-Gamelin park, and being at Lafontaine Park, or the park next door, you know …”(Social Services)

“If they see the Lion King sitting on the couch, while you had to do the grocery shopping … I think there’s no problem!”(Police, Vb)

In the context of an adolescent going out in the evening, several adults compared the current situation with their own experiences as youth growing up in Quebec or in other countries. Contrasts with the countries of origin were drawn by caregivers:

“Everybody knows here when you were in the Caribbean, you were not allowed to go anywhere!

P: Amen!

P: You weren’t allowed to go anywhere unless it’s like up the road with friends. If you wanted to go to an event, it better be church event …”

“Now, when it comes to asking parents to go out, I’m sorry, in my neighborhood that’s something you do not do. They can’t be like ‘oh mommy, there’s a party going down the road can I go’. (…) Your parent like ‘what!’ [inaudible] ‘until you have your own house, until you have your own house, you can decide where you want to go.’”(ACC Caregivers)

“P: I said it depends on where the child is going. It could be to a soccer match … (…) a school event … and if it’s not school event you come on time.”(ACC Caregivers)

Youth also referenced shifts in parental expectations related to their perceptions of danger in the community context.

“Here the parents are more liberal. EN Colombia is very different because they pay more attention to the dangers. Here, there is not much danger.”(P1)

“… in countries like Mexico they are more concerned because there are more dangers on the street such as theft.”(P2)

“… here they are more liberal and give you more confidence because of the security issue. There they put many limits on you as if one is always worried. It is more comfortable for parents because they do not always have to worry but there are dangers.”(P3)

Professionals also recalled their experiences growing up and the differences regarding where young people gathered:

“Let’s say I was going to a little dance, I don’t know what, the other parents were also aware that their children were going there, so there it was like a network of parents who knew we were a group. It’s supervised. I come from the countryside, I was in a social class, it is sure that I could not go anywhere by public transport. Sometimes it was the tractors passing by!”(Police)

The length of time the activity or situation extends can also make a big difference, whether it is used to assess the time children spend home alone after school (“2 h is too long” and “every day and all the time it’s long” (Fr caregiver groups), or to assess the case of a child left alone with an elder:

“If you leave the child for 30 min or 1 h it’s something but the whole day so as not to miss work and the person has difficulty cooking, it’s not appropriate but if it’s for a short time because you’re stuck, it’s ok to troubleshoot.”(Fr Caregivers)

3.2.2. Criteria Variation by Respondent Group

Overall, professionals provided more nuanced analyses of the scenarios presented than did families, resulting in a larger number of assessment criteria mentioned. They concentrated on aspects related to parents and caregivers (most notably, caregiver level of ability and parent responsibility), children (particularly age, maturity, and level of ability), and contextual factors, such as proximity of other people, type and duration of the activity, and location. The role of the DYP was also considered by all professional groups. In contrast, very limited attention was paid to the existence of and access to public and private services to support parents with childcare.

Within professional groups, social service providers were the ones to mention a wider range of criteria and to mention these criteria more often (n = 34 criteria and 276 mentions), followed by the police and educators (n = 33 and 30 criteria, 167 and 129 mentions, respectively). Health care professionals listed the smallest number of criteria (n = 19 criteria and 63 mentions), concentrating largely on contextual factors, and to a much smaller degree, on the basic traits of the children (e.g., level of ability and age). No criteria related to parents, health, or services were listed by the caregivers group.

Compared to the professionals, caregivers and children did not volunteer criteria about parents (except a handful of mentions in regards to parent responsibility and parent-child relationship by caregivers), or family history. Children did not mention any criteria related to health, and only a few pertaining to services and context. In fact, young people focused largely on the level of ability of the caregiver, the maturity and age of the child, the location where the scenario took place, and the duration of the activity/situation described. As for caregivers, the main criteria used to assess appropriateness of care included the caregiver’s level of ability; the maturity, age, and sex of the child; the duration and location of the activity described; and the services available.

4. Discussion

This study provides insights into the experiences of children, caregivers, and family-serving professionals regarding child caregiving and supervision concerning migration and cultural diversity. Caregiver and child competence/ability and contextual factors influence families’ and professionals’ assessment of safety and maturity and the type of supervision they deem appropriate within and outside the physical boundaries of the home. As migrants leave their familiar environment and encounter new social and cultural norms and conditions, parents’ perception of readiness, competence, and safety may change and result in mobility restrictions or the lifting of these restrictions in the receiving society. Thus, for instance, several participants commented on their perceived higher sense of safety in Canada vis-à-vis their country of origin.

Context changes also contribute to shifts in perspectives for residents over time, including second and third generation migrants. Thus, some professionals shared contrasting experiences and views while growing up vs. those in present-day in Quebec. As Grégoire-Labrecque et al. (2020) indicated, this may also be the result of the institutional and professional cultures accompanying their current professional roles. The contextual factors most frequently mentioned by all participants groups were proximity of other people, location, and type and duration of the activity. Other studies have documented the important role of social support networks in the provision of childcare and supervision and in combatting loneliness and other negative emotions that accompany time spent home alone for many children (Ruiz-Casares et al. 2012). In another study regarding migrant children in Montreal who spend time home alone, access to a “cellphone or neighbor who can be trusted” was mentioned as essential when deciding whether a child could stay home alone or with their younger siblings (Ruiz-Casares and Rousseau 2010). Moreover, single parenthood and lack of availability of parents (e.g., if they work evening shifts), the existence of older siblings, and any relatives in town or nearby often resulted in children spending time home alone. Like in our study, children also identified aspects of location (e.g., safe neighborhood) and the activities that they were allowed to engage in (e.g., cooking and leaving the house were often not allowed by parents), and parents generally knew their whereabouts.

In Canada, child welfare legislation is typically written in broad strokes to achieve general application, and specific regulations about child supervision are not always available (e.g., only three provinces have legislated the age at which a child can stay home alone). Social worker discretion in interpreting the legislation is variably guided by provincial policy. However, literal interpretation may produce more problems than it solves. Beyond criticizing or romanticizing the cultural supervision practices of migrants, our findings and professional experience call for a move away from prescriptive policies that set an age for appropriate supervision, as well as from rigid/static policy implementation. Instead, there is a need to carve out space for professional reflection and decision making that respects the ability of the child and other key actors, their context, and their culture on a case-by-case basis. The perspectives of both children and adults are crucial in the assessment of risk and appropriateness of care and the development of solutions/strategies to support families. Indeed, well-rounded training of professionals that includes cultural awareness and skills to engage with migrant parents and children is necessary. In turn, migrants’ experiences and perspectives can help reshape professional practice by means of interpersonal relations and reflection with professionals. Indeed, there is a need to revisit the guidance provided to practitioners to facilitate their relationship with children and their consideration of children’s perspectives in professional assessments, while meeting statutory obligations (Deng et al. 2022; Williams and Parry 2023).

By collecting information from children and parents, we gained a better understanding of their lived experiences regarding child supervision. For example, our participants described how parents prepared children gradually to take responsibility for their own supervision, as well as for that of their siblings. This resonates with conclusions from a recent systematic review showing how migrant children exercise agency in decision making and family life, and how this is key to their healthy development and adaptation (Deng et al. 2022). What our participants described, however, was a teaching and mentoring role not fully captured in provincial legislation and policy. The direct engagement of children in research and decision making is also crucial to the realization of their right to participate in matters that affect them (UNGA 1989). This applies equally to their childcare arrangements, such as deciding (jointly with their caretakers) when they are ready to stay home alone (Ruiz-Casares and Rousseau 2010). Children’s input also helps to inform interventions that respond better to children’s (supervisory) needs and protection. Emphasizing child agency is congruent with the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNGA 1989) and should be reflected in the adaptation of traditional research methods within mobilities research. For instance, the use of participatory and visual methods (e.g., drawing, photographs, video) with migrant children can facilitate their participation and yield rich insights into their lives (Moskal 2017; Vecchio et al. 2017). Child-centered research, however, does not mean excluding adult stakeholders. In fact, there is a growing focus on listening to the voices of parents in child welfare, education, and other sectors (e.g., Koskela 2021), and the nuanced perceptions of professionals are key to understanding how they assess risk and make decisions in cases of lack of supervision.

Some limitations must be noted. A small sample size and the recruitment strategy across all age, professional, and cultural groups prevent us from generalizing these results to these communities. The dynamic nature of culture and its interaction with child rearing practices further contribute to this limitation (Korbin 2002). Self-selection for participation in the study among professionals may have yielded higher levels of cultural awareness than those prevalent among their colleagues/other family-serving professionals It may also be that the people who agreed to participate espoused particularly strong perspectives on appropriate child supervision practices. Limited variation in assessment criteria mentioned by healthcare professionals may at least partly reflect homogeneity within the participants (i.e., all worked closely with migrant families and were committed to helping newcomers integrate into the receiving society, being reticent to report to DYP, and likely to take the blame away from parents and cultural practices). Variable exposure to the country of origin among children—ranging from being born and/or living there for several years, to shorter vacation visits—may influence their familiarity with the day-to-day responsibilities and conditions of child rearing in those contexts.

5. Conclusions

Mobilities, migration, and power relationships are intrinsically connected in the field of child protection. Mobility—spatial, social, economic, and cultural—emerges as a “fundamental underlying concept” (Adey 2017) in the study of childrearing and social integration. It further plays into how migrant families’ child rearing beliefs and practices are shaped by (and in turn, can shape) the values and behaviors of professionals and other community members in the receiving society.

Child supervision practices invariably change in contexts of migration and relocation. The passage of time within increasingly diverse societies also seems to breed changes in perceptions and practices in regards to what constitutes appropriate supervision. Our study documented variations across adult caregivers, youth, and professionals, as well as across cultural groups. Families in our study acknowledge the place of adaptation in parenting in a different geographical and social context. Youth participants either acknowledged this as a challenge for their parents, or credited their parents with making the shift. We urge the integration of our findings in professional assessments of the adequacy of supervision and the policies that guide their work. Thus, professionals working with migrant and culturally diverse families should put their assumptions on hold and rather engage with parents and children in assessing the appropriateness of supervision on an ongoing, case-by-case basis. This will take us beyond a rigid and literal interpretation of legislation and closer to its mission in understanding the difficulties and dynamics of parenting in the context of changes, within both their children and their communities.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.R.-C., R.S. and C.L.; methodology, M.R.-C., C.L., R.S. and P.L.; formal analysis, M.R.-C. and E.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-C. and E.G.; writing—review & editing, C.L., R.S. and P.L.; visualization, M.R.-C. and E.G.; supervision: M.R.-C.; project administration, M.R.-C. and E.G.; funding acquisition, M.R.-C., C.L. and P.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (grant number 430-2015-00839) and Partnership (grant number 895-2011-1015) Grants, by the Centre d’études interdisciplinaires sur le développement de l’enfant et la famille, Université du Québec à Trois-Rivières, Fonds de Recherche du Québec—Santé, and by a gift from the Royal Bank of Canada foundation to support the McGill Centre for Research on Children and Families’ Children’s Services Research and Training Program.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the McGill University Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences (protocol code A12-B57-15A).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to ethical reasons.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the children and adults who participated in this study, as well as the project advisory committee for their guidance, and community-based organizations for their assistance with recruitment. We also thank all the research team members and project coordinators for their valuable input. Special thanks to Christina Klassen, Irene Beeman, Geneviève Grégoire-Labrecque, and Nicole D’Souza for project coordination and implementation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Adey, Peter. 2017. Mobility, 2nd ed. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Arora, Anil. 2019. A Data Story: Ethnocultural Diversity and Inclusion. A Discussion with Statistics Canada. Centre for Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics, Statistics Canada. Available online: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/en/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2019001-eng.pdf?st=A5u5CTt3 (accessed on 17 September 2022).

- Barbour, Rosaline S. 2005. Making Sense of Focus Groups. Medical Education 39: 742–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbour, Rosaline S. 2014. Analysing Focus Groups. In The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Analysis. Edited by Uwe Flick. Hong Kong: SAGE Publications, pp. 313–26. [Google Scholar]

- Chand, Ashok, and June Thoburn. 2005. Research review: Child and family support services with minority ethnic families: What can we learn from research? Child & Family Social Work 10: 169–78. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Juliet, and Anselm Strauss. 2008. Strategies for qualitative data analysis. In Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Zihong, Jianli Xing, Ilan Katz, and Bingqin Li. 2022. Children’s Behavioral Agency within Families in the Context of Migration: A Systematic Review. Adolescent Research Review 7: 1–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, Mónica, Ma Eugènia Gras, Sara Malo, Dolors Navarro, Ferran Casas, and Mireia Aligué. 2015. Adolescents’ perspective on their participation in the family context and its relationship with their subjective well-being. Child Indicators Research 8: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Judith, and Laura Hart. 1999. The impact of context on data. In Developing Focus Group Research. Edited by Rosaline S. Barbour and Jenny Kitzinger. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire-Labrecque, Geneviève, Vicky Lafantaisie, Nico Trocmé, Carl Lacharité, Patricia Li, Geneviève Audet, Richard Sullivan, and Mónica Ruiz-Casares. 2020. ‘Are We Talking as Professionals or as Parents?’ Complementary views on supervisory neglect among professionals working with families in Quebec, Canada. Children and Youth Services Review 118: 105407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Greg, Kathleen M. MacQueen, and Emily E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gurdal, Sevtap, Jennifer E. Lansford, and Emma Sorbring. 2016. Parental perceptions of children’s agency: Parental warmth, school achievement and adjustment. Early Child Development and Care 186: 1203–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafford, Carol. 2010. Sibling caretaking in immigrant families: Understanding cultural practices to inform child welfare practice and evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning 33: 294–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, Bente. 2010. Focus groups as social enactments: Integrating interaction and content in the analysis of focus group data. Qualitative Research 10: 71–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, Ghayda, Brett D. Thombs, Cécile Rousseau, Laurence J. Kirmayer, John Feightner, Erin Ueffing, and Kevin Pottie. 2011. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Appendix 12: Child maltreatment: Evidence review for newly arriving immigrants and refugees. Canadian Medical Association Journal 183: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Hélie, Sonia, Daniel Turcotte, Nico Trocmé, and Marc Tourigny. 2012. Quebec Indicidence Study 2008 (EIQ-2008): Final Report. Montréal: Centre Jeunesse de Montréal-Institut Universitaire. ISBN 978-2-89218-258-3. [Google Scholar]

- Institut de la Statistique du Québec. 2023. International Migration Drove Québec’s Strong Population Growth in 2022. Available online: https://statistique.quebec.ca/en/communique/international-migration-drove-quebec-strong-population-growth-2022 (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- Jonson-Reid, Melissa, Brett Drake, and Pan Zhou. 2013. Neglect Subtypes, Race, and Poverty: Individual, Family, and Service Characteristics. Child Maltreatment 18: 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordan, Joanne, Una Lynch, Marianne Moutray, Marie-Therese O’Hagan, Jean Orr, Sandra Peake, and John Power. 2007. Using Focus Groups to Research Sensitive Issues: Insights from Group Interviews on Nursing in the Northern Ireland “Troubles”. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 6: 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Emma. 2015. Domestic violence, children’s agency, and mother-child relationships: Towards a more advanced model. Children & Society 29: 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klassen, Christina L., Emilia Gonzalez, Richard Sullivan, and Mónica Ruiz-Casares. 2022. ‘I’m just asking you to keep an ear out’: Parents’ and children’s perspectives on caregiving and community support in the context of migration to Canada. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 48: 2762–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korbin, Jill E. 2002. Culture and child maltreatment: Cultural competence and beyond. Child Abuse & Neglect 26: 637–44. [Google Scholar]

- Koskela, Teija. 2021. Promoting Well-Being of Children at School: Parental Agency in the Context of Negotiating for Support. Frontiers in Education 6: 652355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, Richard A., and Mary Anne Cassey. 2015. Focus Groups A Practical Guide for Applied Research, 5th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lansdown, Gerison. 2020. Strengthening child agency to prevent and overcome maltreatment. Child Abuse & Neglect 110: 104398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lavergne, Chantal, Sarah Dufour, Nico Trocmé, and Marie-Claude Larrivée. 2008. Visible Minority, Aboriginal, and Caucasian Children Investigated by Canadian Protective Services. Child Welfare 87: 59–76. [Google Scholar]

- Lumivero. 2015. NVivo, Version 11; Available online: www.lumivero.com.

- Moskal, Marta. 2017. Visual Methods in Research with Migrant and Refugee Children and Young People. In Handbook of Research Methods in Health Social Sciences. Edited by Pranee Liamputtong. Singapore: Springer, pp. 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paat, Yok-Fong. 2013. Working with immigrant children and their families: An application of Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 23: 954–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, Laura J., and Howard Dubowitz. 2014. Child Neglect: Challenges and Controversies. In Handbook of Child Maltreatment. Edited by Jill E. Korbin and Richard D. Krugman. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media, pp. 27–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam, Robert D. 2007. E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century the 2006 Johan Skytte Prize Lecture. Scandinavian Political Studies 30: 137–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putnam-Hornstein, Emily, Barbara Needell, Bryn King, and Michelle Johnson-Motoyama. 2013. Racial and ethnic disparities: A population-based examination of risk factors for involvement with child protective services. Child Abuse & Neglect 37: 33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Casares, Monica, and Cécile Rousseau. 2010. Between freedom and fear: Children’s views on home alone. British Journal of Social Work 40: 2560–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Casares, Mónica, Cécile Rousseau, Janice L. Currie, and Jody Heymann. 2012. “I Hold on to my Teddy Bear Really Tight”: Results from a Child Online Survey on Being Home Alone. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 82: 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawrikar, Pooja, and Ilan Barry Katz. 2014. Recommendations for improving cultural competency when working with ethnic minority families in child protection systems in Australia. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 31: 393–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumacher, Julie A., Amy M. Smith Slep, and Richard E. Heyman. 2001. Risk factors for child neglect. Aggression and Violent Behavior 6: 231–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, Amy, Rebecca Maria Torres, Kate Swanson, Sarah A. Blue, and Óscar Misael Hernández Hernández. 2019. Re-conceptualising agency in migrant children from Central America and Mexico. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 235–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2020. International Migrant Stock 2020. UN Population Division. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/content/international-migrant-stock (accessed on 10 September 2023).

- United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). 1989. Convention on the Rights of the Child. General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989. New York: UNGA. [Google Scholar]

- Vecchio, Lindsay, Karamjeet K. Dhillon, and Jasmine B. Ulmer. 2017. Visual methodologies for research with refugee youth. Intercultural Education 28: 131–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisner, Thomas S., ed. 2005. Discovering Successful Pathways in Children’s Development. Mixed Methods in the Study of Childhood and Family Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Tracey L., and Sarah L. Parry. 2023. The voice of the child in social work practice: A phenomenological analysis of practitioner interpretation and experience. Children and Youth Services Review 148: 106905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Stella M., Zhihuan J. Huang, Renee H. Schwalberg, and Michael D. Kogan. 2005. Parental awareness of health and community resources among immigrant families. Maternal and Child Health Journal 9: 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).