Abstract

The main purpose of this study was to create a global index of perceived job quality that assesses individuals’ perceptions of enjoyment, meaning, and engagement at work, as well as freedom of choice in job selection. The study also explored the correlation between weekly working hours and perceived job quality. A sample of 121,207 individuals from 116 countries was used, sourced from the Gallup World Poll. Additionally, variables from other sources were incorporated to establish the nomological net of the new index. Perceived job quality was highest in South and North America, while it was lowest in East Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Perceived job quality was weakly associated with cultural characteristics at the national level, while it was more strongly associated with experienced positive affect, psychosocial well-being, and optimism. No evidence was found that countries with higher levels of wealth have higher average levels of perceived job quality. The number of hours worked per week was not significantly related to perceived job quality at the national level. Working hours were found to be longer in collectivist, hierarchical, and less free countries, as well as in countries where work is valued over leisure. Weekly working hours was largely unrelated to economic indicators at the national level.

1. Introduction

Work plays a central role in most people’s lives and is a critical factor in psychological well-being (Mira 2021; Blustein 2008). When people in many countries are asked what gives their lives meaning and purpose, job/career is among the most frequently mentioned factors (Silver et al. 2021). Are people satisfied with their jobs? This varies from person to person and from job to job, but research suggests that many people do not perceive their work as fulfilling, even in advanced economies. For example, one study measured people’s well-being at random times of the day (Bryson and MacKerron 2016) and found that being sick in bed and working were associated with lower levels of well-being than about 40 other activities recorded in the study. Thus, although unemployment is a reliable predictor of unhappiness (van der Meer 2012; De Neve and Ward 2017), a low-quality job may not be much of an improvement.

Job quality or quality of working life has been defined in numerous ways, and there is no consensus on what constitutes it (Green 2006; Taipale et al. 2011). The European Commission (2001) has provided a comprehensive definition of job quality: “a relative concept regarding a job–worker relationship which takes into account both objective characteristics related to the job and the match between worker characteristics, on the one hand, and job requirements, on the other. It also involves subjective evaluation of these characteristics by the respective worker on the basis of his or her characteristics, experience, and expectations.” (p. 65). In the present study, job quality is considered to be worker-centered, referring to “what is good for the worker, not what an employer or customer might want (though these can affect the worker’s well-being directly or indirectly)” (Green 2006, p. 9). Many models and frameworks have been developed to explain what constitutes a desirable working life (for reviews, see Cazes et al. 2015; Charlesworth et al. 2014; Stefana et al. 2021). Job quality is considered a complex and multifaceted construct that consists of elements such as labor productivity, employment security, social protection, skill development and training, and work hours, to name a few. Many studies have attempted to measure job quality within a single nation (Miao et al. 2017) or across multiple nations, particularly in European countries (Holman 2012) and OECD countries (Clark 2005). However, there is no recent study that has examined job quality globally.

The present study attempted to fill this gap by analyzing data from the Gallup World Poll from 116 countries across continents and levels of development. The survey also included a variable measuring weekly working hours, which was examined as a potential predictor of job quality in this study. The study had five main objectives:

- (1)

- To develop a new index of perceived job quality at the national level using relevant items from the Gallup World Poll.

- (2)

- To examine the global and regional status of perceived job quality.

- (3)

- To investigate the relationship between the new index of job quality and weekly working hours.

- (4)

- To examine the associations between perceived job quality and a wide range of social, economic, cultural, and well-being variables at the national level.

- (5)

- As a supplementary objective, to examine whether the construct of perceived job quality holds at the individual level as well, and to examine whether it is associated with a number of demographic variables.

2. Defining and Measuring Job Quality

The economics literature typically focuses on the external aspects of job quality such as income levels (Mira 2021). However, it is not only income that matters (Monnot 2015). Since high income does not guarantee optimal levels of engagement and satisfaction, many social scientists advocate a worker-centered approach that focuses on the psychological well-being of the worker (e.g., Green 2006). The present study focused on subjective aspects of job quality, i.e., the extent to which individuals find their work activities enjoyable, significant, engaging, and how much choice they have in their work. Of course, there are other subjective aspects of job quality that deserve attention. However, given that this study used data from the Gallup World Poll, the choice of variables was limited by the availability of items in the data set.

In 2020, the Gallup World Poll included three questions related to perceived job quality in its survey of 116 countries. These three questions capture important subjective aspects of working life, including a sense of enjoyment, significance, and self-determination. In addition to these questions, Gallup’s employee engagement index was used as another aspect of job quality. This index was developed by Gallup using three individual items and a specific weighting scheme. This index divides participants into three groups: Actively disengaged, disengaged, and engaged. These four variables were used together to develop a new index of perceived job quality for 116 countries. The four items were subjected to quantitative data analysis to determine whether they could form a reliable and valid unidimensional construct.

These items capture various aspects of job quality that have been highlighted in previous research. For example, Jones et al. (2014) emphasize the perceived benefits of one’s work to society as a component of job quality. Goods et al. (2019) stress the enjoyment derived from one’s work as a key aspect of job quality. Many studies have found significant associations between engagement and other aspects of job quality and job satisfaction (e.g., Ariza-Montes et al. 2021; del Pozo-Antúnez et al. 2021; Kamalanabhan et al. 2009; Wang et al. 2020). Of course, some of the items in this study do not relate exclusively to the inherent characteristics of the individual’s current job. For example, the question about the freedom to choose work might reflect, to some extent, the range of employment opportunities in an economy and/or the individual’s ability to perform a variety of jobs. However, it is undeniable that a sense of autonomy in choosing or changing jobs or work activities is an important aspect of the subjective quality of a person’s working life (Esser and Olsen 2011). Similarly, the engagement index may be, to some extent, reflective of a person’s commitment to a job or his or her level of motivation, and not necessarily a measure of the inherent quality of a job. Nonetheless, feeling engaged in one’s work (as opposed to being disengaged) represents an important aspect of the quality of working life (Schaufeli 2021). In summary, this perceived job quality index is not intended to only assess the characteristics of a respondent’s current job. Instead, the index attempts to assess people’s subjective feelings about their working life and their interactions with their jobs.

3. Methods

3.1. Participants

The data were drawn from the 2020 Gallup World Poll sample, which included 121,207 individuals (mean age = 39.812, range = 15–99, SD = 16.696, females = 48.9%) from 116 countries in which work-related questions were asked. The data were collected between March 2020 and March 2021. More information on Gallup’s global data and study procedures is available at https://www.gallup.com/analytics/318875/global-research.aspx (accessed on 1 February 2022). The three questions regarding enjoying work, perceived significance of work, and having choices were asked only of respondents who reported being employed by an employer or self-employed (N = 76,712, percentage of total sample = 63.3%). The working hour per week question was asked of the same group of participants, and 61.7% of the sample provided their responses (N = 74,785). The engagement index was available only for participants who reported being employed by an employer (N = 49,164, percentage of total sample = 40.6%). The engagement index was not available for Tajikistan. More information on sample sizes is reported in Table S1.

3.2. Measures

3.2.1. Perceived Job Quality

This index was constructed by averaging four variables at the national level. Included were three items added to the survey in 2020 with a yes/no response format asking about enjoying work, perceived significance of work, and having choices. The questions were “Do you enjoy the work you do in your job every day, or not?”, “Do you think the work you do in your job significantly improves the lives of other people outside of your own household, or not?”, and “Do you, personally, have many choices in regard to the type of work you can do in your life?”. Along with these items, the 2020 Gallup World Poll included an index of employee engagement that categorized participants into three groups: Actively disengaged, not engaged, and engaged based on their responses to three items (the data for the individual items are not released). The perceived job quality index was calculated at the national level. In each country, the percentages of participants who answered “yes” to the three job-related questions were first calculated. The percentage of people classified as “engaged” in the engagement index was also calculated. This resulted in four percentage variables for each nation. The four percentages were then averaged to calculate a perceived job quality index for each country.

3.2.2. Working Hours

Participants who reported being employed by an employer or self-employed were also asked about the total number of hours they worked per week, with these options: 1 = less than 15 h, 2 = 15 to 29 h, 3 = 30 to 39 h, 4 = 40 to 49 h, 5 = 50 or more hours. Thus, the responses range between 1 and 5, with higher scores showing longer working hours per week.

3.2.3. Gallup World Poll-Based Measures of Well-Being

Some well-being variables commonly used in Gallup World Poll studies were included (Helliwell et al. 2021; Joshanloo 2018). Positive affect was measured by two questions asking respondents if they enjoyed themselves most of the day and if they smiled or laughed a lot yesterday. The negative affect scale consisted of four questions asking participants if they felt anxious, sad, stressed, or angry most of the day yesterday. To assess optimal psychosocial functioning, the eudaimonic well-being index (Joshanloo 2018) was used. This indicator was composed of seven Gallup World Poll questions that assessed learning experiences, social support, respect, efficacy, freedom, and social interest. However, the component related to efficacy was not included in 2020 and was, therefore, omitted. To determine life satisfaction, participants were asked which step of the life ladder they felt they were on, from 00 = worst possible to 10 = best possible. Future life satisfaction was measured by asking participants where they thought they would be in the future.

3.2.4. Other Gallup-Based Variables

Two other national variables were calculated based on two Gallup items. Percentage of participants per country that chose “getting better” in response to “Right now, do you feel your standard of living is getting better or getting worse?”, and those who chose “good time” in response to “Thinking about the job situation in the city or area where you live today, would you say that it is now a good time or a bad time to find a job?”.

3.2.5. Cultural Dimensions

Hofstede’s main cultural dimensions commonly used in multi-national research were used (Hofstede et al. 2005): Individualism/collectivism (the strength of attachment to one’s ingroups), power distance (the extent to which power inequality between people is accepted), masculinity (the extent to which men’s and women’s roles do not overlap), and uncertainty avoidance (the extent to which uncertainty is accepted). To measure the extent to which national cultures value work and leisure, joint data from the World Values Survey-Wave 7, collected during 2017–2021, and the European Values Survey-Wave 5, collected during 2017–2020, were used (EVS/WVS 2020). Two questions asked respondents to “For each of the following, indicate how important it is in your life”: Leisure time and work. For each nation, two variables were calculated showing the percentage of people per country who chose the “very important” option for each question. Another variable showed the percentage of participants per country who selected “very important” in response to the question “Here is a list of qualities that children can be encouraged to learn at home. Which, if any, do you consider to be especially important? Please choose up to five!”.

3.2.6. Social and Economic Indicators

Income inequality was measured using the Gini index estimated by the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SI.POV.GINI, accessed on 1 February 2022). To decrease missing values as much as possible, scores from 2016 to 2019 (the latest available years) were averaged for each country. The latest available gender inequality index (2019) estimated by the United Nations Development Programme was used (http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/gender-inequality-index-gii, accessed on 1 February 2022). This index quantifies gender disadvantages in three areas: Reproductive health, empowerment, and the labor market. The annual percentage growth rate of Gross Domestic Product in 2020 was used as estimated by the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG, accessed on 1 February 2022). The 2020 corruption perceptions index was used to measure corruption (https://www.transparency.org/en/cpi/2020/index/nzl#, accessed on 1 February 2022). This index quantifies the perceived level of corruption in the public sector in each country. The urbanization variable measures the proportion of the total population that is urban, as estimated by the World Bank in 2020 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.URB.TOTL.IN.ZS, accessed on 1 February 2022). The female labor force participation variable measures the ratio of female to male labor force participation in 2019 (the latest available year) as modeled by the International Labour Organization (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FM.ZS, accessed on 1 February 2022). The unemployment in 2020 was measured using the unemployment rate (% of the total labor force) estimated by the World Bank (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS, accessed on 1 February 2022). The ease of doing business index assesses how friendly the regulatory climate was for starting and running a local firm in 2020 (https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/rankings, accessed on 1 February 2022). Finally, the Legatum Prosperity Index, related to 2020 was included, consisting of 12 scores for each nation measuring the fundamental pillars of national prosperity: Economic quality, education, enterprise conditions, governance, health, investment environment, living conditions, market access and infrastructure, natural environment, personal freedom, safety and security, social capital (https://www.prosperity.com, accessed on 1 February 2022).

3.3. Statistical Software

The analyses presented in this study were conducted using SPSS 29 and Mplus 8.7.

4. Results

4.1. Constructing Perceived Job Quality Index

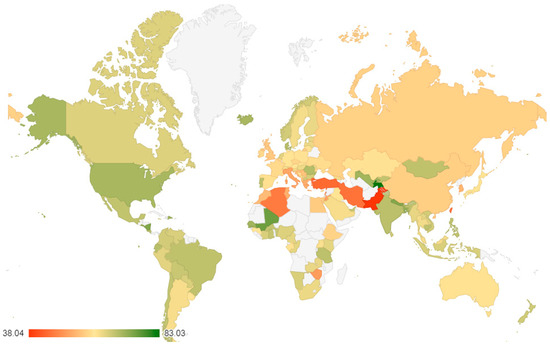

Table 1 shows the Spearman correlations between the four variables that constitute the job quality index at the national level. The correlations were significant and positive. A principal axis factoring was performed at the national level with the four job quality variables. This analysis showed that a one-factor model is consistent with the data. A single factor with an eigenvalue of 2.284 explained 57.102% of the variance in the variables. The second eigenvalue was 0.750. Factor loadings ranged between 0.767 (improve life) and 0.488 (engaged). The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.727 suggesting acceptable internal consistency despite the short length of the scale. The four variables were averaged to construct an index of perceived job quality for 116 countries (M = 62.439, SD = 6.740). The national scores are reported in Table S2 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations for the four items.

Figure 1.

Perceived job quality. Grey color indicates no available data.

4.2. Correlations with Working Hours at National Level

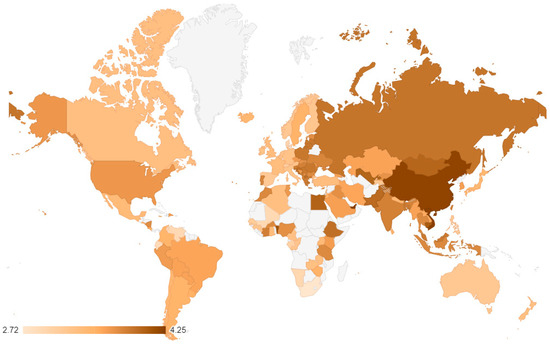

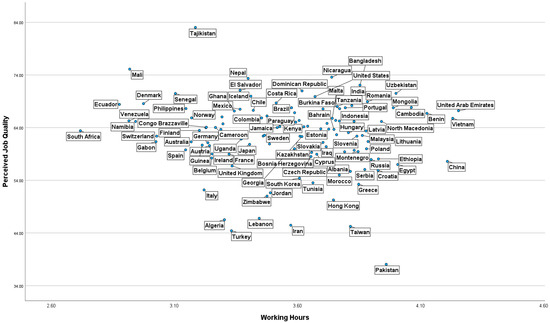

The weekly working hours scores (ranging between 1 and 5) were averaged in each country to construct a measure of national working hours (M = 3.566, SD = 0.314). Higher scores indicate longer working hours per week. The national scores are shown in Figure 2 and Table S2. Working hours and job quality were not significantly correlated (Spearman r = −0.088). Figure 3 shows that the association between working hours and job quality at the national level was trivial.

Figure 2.

Working hours. Grey color indicates no available data.

Figure 3.

The association between working hours and job quality at the national level.

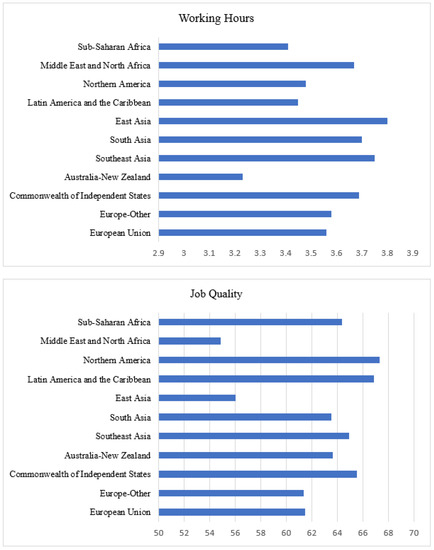

4.3. Regional Averages of Job Quality and Working Hours

Figure 4 shows the average job quality and working hours in 11 world regions. Working hours were longest in East Asia and shortest in Australia and New Zealand. Perceived job quality was highest in North America and lowest in the Middle East and North Africa. Table S3 shows the countries that fall into each of the regions.

Figure 4.

Regional averages for working hours and job quality.

4.4. Correlations with Country-Level Variables

One of the objectives of the study was to establish the nomological networks of perceived job quality and working hours. To this end, the correlations between these variables and a large set of national variables were calculated. These correlations are reported in Table 2. While working hours were primarily associated with personal freedom and cultural variables, job quality was mainly related to national well-being and perceptions of living standards and the job market.

Table 2.

Correlations at The National Level.

4.5. Supplementary Individual-Level Analysis

Although the focus of the study was at the national level, supplementary analyses were conducted at the individual level to provide preliminary results concerning basic demographic variables. A principal axis factoring using the robust weighted least squares (WLSMV) estimator was conducted to examine whether the four items constitute a single factor at the individual level. This estimator is appropriate for categorical indicators (Brown 2015; Kline 2023), as is the case with the present analysis. Results indicated that a unidimensional factor structure was consistent with the data, first eigenvalue = 1.925 (the second eigenvalue = 0.811), with factor loadings ranging from 0.726 (enjoyment of work) to 0.477 (engaged). These results suggest that the construct of job quality also holds at the individual level. Accordingly, in a regression model, some demographic variables were used as potential predictors of personal job quality: Individual working hours, age, gender, education level, place of residence, and employment status. To account for the nested data structure (individuals within nations) and the categorical nature of the perceived job quality index (ranging from 0 to 4), a Bayesian multilevel analysis was performed1. The results are presented in Table 3. As can be seen, hours worked, age, and secondary and tertiary education (as opposed to elementary education) were positive predictors of job quality at the individual level. Being a woman, living in a small town or village (as opposed to a large city), and being self-employed and having a part-time job (as opposed to full-time employment for an employer) were negative predictors of job quality at the individual level. Based on the standardized regression coefficients, tertiary education was the strongest predictor of job quality among all predictors. Together, the predictors explained about 2.5% of the variance in job quality (R2 = 0.024).

Table 3.

Parameter Estimates For Multi-Level Model Predicting Job Quality Using Individual-Level Predictors.

5. Discussion

Job quality is a fundamental dimension of human well-being because working conditions affect not only people’s quality of life but also national progress. Four items from the Gallup World Poll were considered relevant to the construct of perceived job quality and were included in this study. The four-item scale was internally consistent and had a one-factor structure, confirming that the index has satisfactory statistical properties at the national and individual levels.

5.1. Perceived Job Quality

Perceived job quality is highest in the Americas and lowest in East Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa. Cultural values and dimensions do not contribute much to explaining differences in job quality across countries. Desirable Economic indicators are also either unrelated to perceived job quality (such as GDP growth, economic quality and enterprise conditions) or weakly and negatively related to it (such as living conditions, infrastructure and market access, and ease of doing business). Overall, this pattern of relationships suggests that greater national wealth does not guarantee higher perceived job quality. It may also indicate that people in wealthier countries use stricter standards and expectations when assessing the quality of their working lives. While perceived job quality is only weakly related to economic indicators, it is most strongly associated with certain aspects of national well-being, including eudaimonic well-being, positive affect, and future life satisfaction. These three variables of well-being are categorized by Joshanloo et al. (2019) as indicators of psychosocial functioning that are distinct from the indicators of socioeconomic progress at the national level. Perceived job quality was not related to life satisfaction, which is closely related to economic indicators (Joshanloo et al. 2019). Perceived job quality was also positively related to people’s perception that the job market is good and their expectation that their standard of living will improve.

5.2. Working Hours

Although some models and frameworks consider working hours as an element of job quality (Leschke and Watt 2013), the present study found that national levels of weekly working hours were unrelated to national levels of perceived job quality. Working hours was also weakly related or unrelated to a comprehensive set of national well-being indicators. A recent comprehensive analysis of working hours at the individual level also failed to demonstrate a robust direct causal link between working hours and physical or mental well-being (Ganster et al. 2016). Possibly, it is not the number of hours worked that matters, but how satisfied people are with the number of hours they work. The results showed that working hours are longer in Asian countries, while they are shortest in Australia, New Zealand, Sub-Saharan Africa, and the Americas. The pattern of intercorrelations with other variables suggests that collectivist, hierarchical, and less free countries have longer working hours. Countries that place a high value on work and a low value on leisure also tend to have longer working hours. As shown in Table 2, weekly working hours is not strongly associated with economic indicators. However, these results should be interpreted with one caveat: weekly working hours was measured categorically, not in hours, but in intervals (i.e., from “less than 15 h” to “50 or more hours”). Importantly, these intervals are not of equal length, and the last category has no upper limit. Future research could consider measuring working hours in hours or in intervals of equal length to achieve greater precision and accuracy in the analyses.

5.3. Supplementary Analysis at the Individual Level

The results of the individual-level factor analysis indicated that a single-factor structure was consistent with the data. Thus, the construct of job quality measured by the four items applies to individuals as well as nations. A regression analysis accounting for the nested structure of the data showed that working hours and demographic variables were significant determinants of an individual’s job quality. The most important predictor was having tertiary education. A full-time job working for an employer proved to be a positive predictor of job quality after controlling for all other explanatory variables. Notably, weekly working hours, which showed virtually no association with job quality at the national level, was a positive (albeit weak) predictor of job quality at the individual level.

6. Concluding Remarks and Direction for Future Research

Taken together, these results suggest that perceived job quality at the national level is primarily related to the extent to which people in a country experience positive feelings, perceive themselves as psychologically and socially competent, and are optimistic about the future. At the individual level, a person’s level of education and employment status appear to be most important for perceived job quality, but the effects at this level are small. These results show only global trends, and studies in individual countries may find effects or different directions or magnitudes. Overall, these results suggest that improving a country’s economic indicators may not necessarily lead to improvements in perceived job quality, if it is not accompanied by improved psychosocial well-being and cultural values. Therefore, improving job quality requires a holistic approach that considers not only economic factors, but also the psychosocial well-being and cultural characteristics of the population.

Data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many people’s jobs had new characteristics during this time. Therefore, it is possible that perceived job quality during this period differed from job quality before the pandemic. The pandemic likely had an impact on many people’s work lives, but the nature and magnitude of this impact cannot be assumed and must be studied empirically. For example, many expected the pandemic to have enormous effects on people’s overall life evaluation, but global results showed that the pandemic’s effects on life satisfaction were not large (Helliwell et al. 2021). In some countries, subjective well-being remained unchanged or even improved slightly in 2020. It is also possible that the pandemic did not have a large impact on subjective job quality at the global level. One of the variables in the study, the percentage of people classified as engaged at work, was also included in the Gallup World Poll prior to the pandemic, so it is possible to compare engagement levels in 2020 with earlier years. The global percentage of people classified as engaged was 17.9% in 2018, 19.2% in 2019, and 19.7% in 2020. Although the countries included in each year vary, this comparison at least shows that there was no engagement crisis in 2020. However, the pandemic has undeniably affected people’s working lives in many ways, which must be taken into account when interpreting the current results. In any case, the impact of the pandemic on various aspects of job quality remains to be further investigated in future studies.

The development of this index provides policymakers and organizations with an effective means of measuring the quality of work life at the national level to improve worker satisfaction and overall well-being worldwide. However, this study is only a preliminary examination of the global and regional status of job quality and its relationship with some national variables. While the results are informative, they highlight the need for further research to fully understand the complex and nuanced nature of job quality and its determinants. Future studies should look more closely at the local and regional factors that influence perceived job quality. It would be useful to examine how national characteristics such as wealth, political freedom, and cultural values may attenuate the relationship between individual predictors such as hours worked per week and age and perceived job quality. In summary, this study provides valuable insights into the determinants of perceived job quality, but it is only the beginning of a broader and more comprehensive investigation of this complex and important topic.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci12090492/s1, Table S1: Sample Sizes. Table S2: National Scores. Table S3: Global Regions.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Well-being for Planet Earth Foundation awarded in 2021.

Institutional Review Board Statement

No data collection was conducted for the purposes of this study. All data used were obtained from secondary sources. As a result, the requirement for Institutional Review Board approval was deemed unnecessary.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from each participant as a routine part of Gallup’s data collection process.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are freely available from the original sources, with the exception of Gallup data, which are available for a fee (https://www.gallup.com/analytics/318875/global-research.aspx, accessed on 1 February 2022). Gallup-based indices developed and used in this study are provided in the Supplementary Materials, Table S2.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Mplus was used for Bayesian multilevel modeling. Two Markov chain Monte Carlo chains were used with the GIBBS (PX1) algorithm and 10,000 draws (the first half was used as burnin by default) and the default priors of Mplus (Muthén et al. 2017). Posterior distributions were recorded at every 10th iteration. Age and working hours were group-mean centered. Regression effects were set as fixed effects. The potential scale reduction factor of the model was 1.000, indicating convergence. Additionally, the Bayesian plots showed optimal chain mixing and autocorrelation. |

References

- Ariza-Montes, Antonio, Aleksandar Radic, Juan M. Arjona-Fuentes, Heesup Han, and Rob Law. 2021. Job quality and work engagement in the cruise industry. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research 26: 469–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, David L. 2008. The role of work in psychological health and well-being: A conceptual, historical, and public policy perspective. American Psychologist 63: 228–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Timothy A. 2015. Confirmatory Factor Analysis for Applied Research. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bryson, Alex, and George MacKerron. 2016. Are you happy while you work? The Economic Journal 127: 106–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazes, Sandrine, Alexander Hijzen, and Anne Saint-Martin. 2015. Measuring and Assessing Job Quality: The OECD Job Quality Framework. Paris: OECD. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charlesworth, Sara, Jennifer Welsh, Lyndall Strazdins, Marian Baird, and Iain Campbell. 2014. Measuring poor job quality amongst employees: The VicWAL job quality index. Labour and Industry 24: 103–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, Andrew E. 2005. Your money or your life: Changing Job quality in OECD countries. British Journal of Industrial Relations 43: 377–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Neve, Jan Emmanuel, and George Ward Ward. 2017. Happiness at work. In World Happiness Report 2017. Edited by John Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey Sachs. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network, pp. 144–77. [Google Scholar]

- del Pozo-Antúnez, Jose Joaquin, Horacio Molina-Sánchez, Antonio Ariza-Montes, and Francisco Fernández-Navarro. 2021. Promoting work engagement in the accounting profession: A machine learning approach. Social Indicators Research 157: 653–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esser, Ingrid, and Karen M. Olsen. 2011. Perceived job quality: Autonomy and job security within a multi-level framework. European Sociological Review 28: 443–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2001. Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion. In Employment in Europe 2001: Recent Trends and Prospects. Belgium: European Communities. [Google Scholar]

- EVS/WVS. 2020. European Values Study and World Values Survey: Joint EVS/WVS 2017–2021 Dataset (Joint EVS/WVS). Dataset Version 1.0.0. Madrid and Vienna: JD Systems Institute & WVSA Secretariat. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganster, Daniel C., Christopher C. Rosen, and Gwenith G. Fisher. 2016. Long working hours and well-being: What we know, what we do not know, and what we need to know. Journal of Business and Psychology 33: 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goods, Caled, Alex Veen, and Tom Barratt. 2019. “Is your gig any good?” Analysing job quality in the Australian platform-based food-delivery sector. Journal of Industrial Relations 61: 502–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Francis. 2006. Demanding Work: The Paradox of Job Quality in the Affluent Economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helliwell, John F., Richard Layard, Jeffrey Sachs, and Jan-Emmanuel De Neve, eds. 2021. World Happiness Report 2021. New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstede, Geert, Gert Jan Hofstede, and Michael Minkov. 2005. Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. New York: Mcgraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Holman, David. 2012. Job types and job quality in Europe. Human Relations 66: 475–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Wendy, Roger Haslam, and Cheryl Haslam. 2014. Measuring job quality: A study with bus drivers. Applied Ergonomics 45: 1641–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, Mohsen. 2018. Optimal human functioning around the world: A new index of eudaimonic well-being in 166 nations. British Journal of Psychology 109: 637–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshanloo, Mohsen, Veljko Jovanović, and Tim Taylor. 2019. A multidimensional understanding of prosperity and well-being at country level: Data-driven explorations. PLoS ONE 14: e0223221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamalanabhan, T. J., L. Prakash Sai, and Duggirala Mayuri. 2009. Employee Engagement and Job Satisfaction in the Information Technology Industry. Psychological Reports 105: 759–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kline, Rex B. 2023. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Leschke, Janine, and Andrew Watt. 2013. Challenges in Constructing a Multi-dimensional European Job Quality Index. Social Indicators Research 118: 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Yang, Lingui Li, and Ying Bian. 2017. Gender differences in job quality and job satisfaction among doctors in rural western China. BMC Health Services Research 17: 848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mira, María Cascales. 2021. New model for measuring job quality: Developing an European intrinsic job quality index (EIJQI). Social Indicators Research 155: 625–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monnot, Matthew J. 2015. Marginal utility and economic development: Intrinsic versus extrinsic aspirations and subjective well-being among Chinese employees. Social Indicators Research 132: 155–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthén, Bengt O., Linda K. Muthén, and Tihomir Asparouhov. 2017. Regression and Mediation Analysis Using Mplus. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén. [Google Scholar]

- Schaufeli, Wilmar. 2021. Engaging leadership: How to promote work engagement? Frontiers in Psychology 12: 754556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, Laura, Patrick van Kessel, Christine Huang, Laura Clancy, and Sneha Gubbala. 2021. What Makes Life Meaningful? Views from 17 Advanced Economies. Washington, DC: Pew Research Center. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2021/11/18/what-makes-life-meaningful-views-from-17-advanced-economies/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Stefana, Elena, Filippo Marciano, Diana Rossi, Paola Cocca, and Giuseppe Tomasoni. 2021. Composite indicators to measure quality of working life in Europe: A systematic review. Social Indicators Research 157: 1047–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taipale, Sakari, Kirsikka Selander, Timo Anttila, and Jouko Nätti. 2011. Work engagement in eight European countries. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 31: 486–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Meer, Peter H. 2012. Gender, unemployment and subjective well-being: Why being unemployed is worse for men than for women. Social Indicators Research 115: 23–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Chaohui , Jiahui Xu, Tingting Christina Zhang, and Qinglian Melo Li. 2020. Effects of professional identity on turnover intention in China’s hotel employees: The mediating role of employee engagement and job satisfaction. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 45: 10–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).