Abstract

Bridging the Pacific provides an image of two separate regions which share the Pacific Rim, becoming connected in multiple aspects, not limited to a predominantly economic interconnection. This image, thus, points toward a constructive mechanism to work toward a resolution of the over-arching global issue, including climate change. This image and the method for its practical implementation are suggested by the Forum for East Asia and Latin America Cooperation—FEALAC. In the overall field of regionalism studies, inter-regionalism can be considered as ‘the third wave’ under the new regionalism, and FEALAC can be located in this analytical framework. To begin, this paper traces the process and features of regionalism by typification of three different versions, or ideal types of regionalism. In this work, each type of regionalism is not viewed as a successor to, considered better than the previous one, but rather provides a typology for analytical purposes. Next, taking up this historical and analytical framework of regionalism, this paper examines the FEALAC in terms of its strengths and weaknesses considered from the perspective of the five systemic functions. Finally, this paper demonstrates the ways in which FEALAC can be considered a relevant framework of inter-regional governance.

1. Introduction

What makes inter-regional governance critical for the future of global governance? Among the various inter-regional entities, what is FEALAC? Is FEALAC just a ‘meeting’ or ‘process?’ Or, is it a ‘framework’ or an ‘institution’? How does FEALAC add value to East Asia–Latin America relations within the myriad entities, including APEC,1 Korea-SICA,2 China–CELAC,3 PBEC,4 and PECC?5 Finally, we ask if there is an Asia–Pacific identity,6 and does FEALAC support its formation or vice versa?

With so many competing inter-regional frameworks, raising the question of FEALAC’s role and identity is indeed pertinent. One possibility is that FEALAC might be the overarching framework in which all other above bilateral and inter-regional fora should be subsumed. Another alternative is that FEALAC may remain just one of the many extant frameworks. If the latter, then it is necessary to address what are FEALAC’s unique comparative advantages, and what manner of added value which FEALAC could offer compared to the other frameworks and fora. Given the nature of FEALAC, which was established in 2000, its institutionalizing process has been paid scant attention, which this paper will rectify by examining the historically embedded features of FEALAC and possible ways to raise awareness of it, which should focus on the non-traditional security realm, including agendas for climate change adaptation.7 “This focus may lead toward a path for FEALAC’s identity, which may be termed the ‘FEALAC Way.’ By adopting the notion of Higgott (1994) and Amitav (1997), the Asia-Pacific identity has been formed by a networking activity, which is facilitated by ‘open-regionalism’, ‘cooperative security’, soft regionalism, and consensus. These aspects are highly shaped by the ideas and cultural norms provided by a critical inter-subjective framework for interactions and socialization. In this vein, the ‘FEALAC way’ can be adopted by these aspects, particularly by the consensual and cautious approach extrapolated from the ASEAN Way (Amitav 1997, p. 319).

In this realm, FEALAC emphasizes the global issue at the inter-regional level via south–south cooperation, articulating the post-hegemonic actor in inter-regional cooperation (Riggirozzi and Tussie 2012, p. 18). To see where the FEALAC can gain a footing and further expand its institutional territory, this study reflects on the FEALAC via the existing knowledge on the varieties of regionalism and based on the overarching global agenda. In other words, this paper demonstrates how and in what ways FEALAC will play as a critical role in supporting cooperation not only at the inter-regional level but also potentially at the global and local level, given that the global agenda is not solely as global as it should be.

The raison d’etre of the FEALAC is to establish the missing inter-regional link between East Asia and Latin America. The purpose of the forum was formulated at the first Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (FMM) in 2001, “[T]o promote better understanding, political and economic dialogue and cooperation in all areas so as to achieve more effective and fruitful relations and closer cooperation between the two regions” (fealac.org). Additionally, at the first FMM, FEALAC outlined its basic principles, “[T]he forum should be forward looking and future-oriented. It will be voluntary, informal and flexible in its working procedures. It will conduct itself in accordance with basic principles of international law (FEALAC 2015).”

These principles include:

- Respect for each other’s sovereignty and territorial integrity;

- Non-interference in each other’s internal affairs;

- Equality, mutual benefit, and the common goal of development;

- Respect for each other’s unique cultures and social values;

- Decision-making by consensus.

This underlying orientation of FEALAC demonstrates how it has developed over time. Currently, FEALAC is entering its third decade since its inception, and, as in accordance with its design, the FMM and preliminary meetings are held every two years. Each FMM produces its own declaration based on the consensus of member countries. The FMM declaration, along with various meetings at different levels, indicate how FEALAC progresses under the auspices of the concept of regional governance, with special reference to the inter-regional level.

Given the scope and purpose of this paper, the structure is as follows: First, we explore how and where inter-regionalism can be located in the realm of regionalism studies, and the ways in which inter-regionalism is crucial in understanding regionalism and globalism. Second, we critically study the process of inter-regionalism, particularly for the purpose of analyzing FEALAC. Third, we bring up the notion of the necessity of special features, which may include institutional development or the flagship projects. This will be critically assessed by the notion of five systemic functions. Within this exploration, the paper discusses the notion of global issues including climate change, which is an aspect that FEALAC should target to enter into the global realm and become a truly global institution beyond the inter-regional realm. This concluding section reflects on how and in what ways FEALAC identity along with the process of institution building can be employed for global issues. This includes climate change in the framework of inter-regional governance, with special a focus on FEALAC.

2. Theoretical Underpinnings of Regionalism

In what ways does the notion of regionalism come into play in the global sphere, how does it evolve, and why has regionalism appeared? Where is inter-regionalism located in the process of regionalism?

There is little doubt that the narrative of regionalism and its process is highly related to the emergence of the European Union (Hurrell 1995; Katzenstein 1996; Gamble and Payne 1996; Amitav 2014). In other words, the EU’s experience has been the reference point in developing the regionalism-related literature. The scholarship has been focused on explaining European integration, with the EU as the object of study. From an analytical point of view, the EC(U)’s regionalism is known as old regionalism, the first wave regionalism, or the first generation of regionalism (Söderbaum 2015). In this vein, several theoretical approaches have been developed to address old regionalism, including functionalist theories (Mitrany 1948), neofunctionalist approaches (Haas 2009), and inter-governmentalist theories (Hoffman 1966).

As will be shown below, the image of the first wave of regionalism was ‘the ocean,’ as a metaphor of realism. Given that realism became the dominant paradigm in international relations theory, Mitrany argued that the peace is feasible through the concept of “the effect of ramification.” The metaphor of ramification includes functional cooperation with a special emphasis on societal and the economic relations among nation-states. If taken to its logical conclusion, it could eventually achieve world peace. Mirany supported the need to limit the supranational organization’s power and ensure its functional and technical nature. His concept was employed and also mutually reinforced by the European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) and later by the European Economic Community (EEC).

This perspective was criticized by Haas, who pointed out that politics is the necessary realm for moving forward, with his concept of the ‘spill-over effect.’ In other words, a sole area of cooperation would not necessarily continue onwards to the next step, and thus it would need deliberative political decision-making for advancement to the next level of cooperation. In addition, neofunctionalists believed that high levels of economic interdependence would lead to greater political integration (Hwee and Vidal 2008). However, this perspective is also criticized by the inter-governmentalists, who argued that nation-states remain the system’s main political entity, in spite of the timid transfers of authority via the spillover effect. In this vein, Hoffman, who is a leading figure in this inter-governmentalist camp, stated that, “[s]tates were willing to create supranational organizations to coordinate various economic policies (i.e., low politics) but not to deal with issues such as security and diplomacy (i.e., high politics)” (Hwee and Vidal 2008, p. 40). In short, there is, to some degree, a transfer of sovereignty to supranational organizations, but the states ultimately supervise the decisions made by such organizations.

The Eurocentric approach to regionalism has also received heavy criticism, particularly from Gamble and Payne (1996), who argue that there is “excessive attention paid by regional integration theorists to institutions, on the grounds that it is merely an observation applicable to the European case and not a universal parameter” (Hwee and Vidal 2008, p. 41). Europe is just one of several regions which can be viewed as ‘regional worlds,’ a concept developed by Amitav Acharya (Amitav 2018, p. 99). Moreover, regionalism takes place without the creation of large, formal organizations, often through the commercial activity of non-state actors, such as in the case of APEC. These cases indicate that the Eurocentric approach, or ‘old regionalism’, proved less capable of explaining the regionalism process outside of Europe. This led to the emergence of a regionalism-related scholarship that came to be known as ‘new regionalism.’ The second wave of regionalism emerged largely due to the collapse of the bipolar world of the Cold War. The explanatory limitations of the old regionalism were due to the changing context after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the emergence of a post-hegemonic and post-Eurocentric ideology.

2.1. New Regionalism as the Second Wave of Regionalism

New regionalism is characterized, first and foremost, by its multidimensional nature and it has five distinctive features. Firstly, this new wave of regional projects was initially confined to the economic component. The first feature is the liberalization of the economies that came together in such projects setting this new trend apart from the old regionalism, which was much more protectionist (Amitav 2018, p. 42). This process is also called ‘regionalization’, which defines a trade-driven, bottom-up process (Hänggi et al. 2006, p. 4). It also includes monetary policy and security-related projects, such as the ASEAN+3 and EAS (East Asia Summit). Secondly, the economic aspect in the new regionalism is driven by the critical juncture, which is the demise of bipolar order. This ‘end of history’ provides a room to maneuver for open-regionalism. Thirdly, the new regionalism is more flexible and informal, leaving behind the much more institutionalized structures of Europe’s old regionalism. To reiterate, new regionalism is characterized by informal rules and consensus-based decision-making processes. Fourthly, in the second wave of regionalism, ‘Global South’ regionalism has received more attention compared to the fact that old regionalism was more attentive to ‘Global North’ regionalism, refereeing to the EU. Fifthly, many different types of actors come into play in the second wave of regionalism. Although new regionalism does not refute that state is a key actor, non-state actors are critically important in the new wave of regionalism. Multinational Corporations (MNCs), Business Associations, INGOs and local governments, amongst others, have taken roles in the complex structure of global governance. To reiterate, this multi-dimensionalism leads to increased interdependencies between geographically adjacent states, societies, and economies (Hänggi et al. 2006, p. 4). Hwee and Vidal (2008) stated that the second wave of regionalism “result [s] in a greater capacity for action in a variety of contexts” (Hwee and Vidal 2008, p. 44). Elaborating on this theme, Söderbaum and Langehove argued that this greater internal cohesion (regionness) and its ability to influence the environment (actorness) have led to the need for interaction between regions. This invites the degree of inter-regionalism which can be considered as the third wave of regionalism or third-generation regionalism (Söderbaum and Van Langehove 2006, p. 139).

2.2. Inter-Regionalism and Its Features under the Third Wave of Regionalism

The key aspect, amongst others, in the wave of inter-regionalism can be recognized as ‘cooperative balancing.’ This concept was coined by Link (1998) to describe the situation that applied during the 1990s and afterwards, when economic globalization created new competitive pressure to which nation-states have responded with regional cooperation. The emerging regional blocs, however, are characterized by (economic) power disequilibria, to which regional organizations seek to adjust by (institutional) balancing. It is this management of interdependence and polarization through balancing and ‘bandwagoning’ which gives rise to the emergence of flexible inter-regional structures of cooperation (Hänggi et al. 2006). In short, balancing the phenomenon of ‘unevenness’ is a feature of inter-regionalism per se. This aspect sheds light on the rationale and process by which the inter-regionalism takes place and develops beyond the ‘open-regionalism,’ which is a feature of new regionalism. Currently, there are two different features which emerge in inter-regionalism: (1) Triad regions, the leading regions in the world economy, namely, North America, Europe, and East Asia (excluding Japan), and (2) the appearance of additional forums of this nature, linking the Triad with non-Triadic regions, and connecting regions at the periphery of the Triad with each other. In this vein, the inter-regionalism can be categorized as taking three different forms. First, relations between regional groupings; second, the bi-regional and trans-regional arrangements, and third, the hybrid regions such as relations between regional groupings and single powers. These three different forms of inter-regionalism are grouped by region.

The three different types have distinctive features. The first type between the regional groupings is the EU’s traditional group-to-group dialogues which were carried out over the 1970s and can be considered the prototype of inter-regional arrangements. This relationship is closely linked to “old regionalism” (Hänggi 2000, p. 4). In short, the feature of this type is a ‘hub-and-spokes’ system, due to the fact that EC was the most advanced regional entity and had relations with other regional groupings, particularly ASEAN. However, with the end of the Cold War, this first type of inter-regional relations gave rise to another arrangement. Thus, the global network of group-to-group relations expanded beyond the EU-dominated ‘hub-and-spoke’ system (Hänggi 2000, p. 4). As shown in Table 1, there are other types of group-to-group relations in this respect, particularly ASEAN with other regional groupings.

Table 1.

Typology of three different forms of inter-regionalism.

The second type of inter-regionalism is the bi-regional and trans-regional arrangement. Its membership is rather heterogenous and so more diffuse than in traditional group-to-group dialogue (Hänggi 2000, p. 6). There are five significant bi-regional or trans-regional linkages that have been established between the Americas, Europe, East Asia, Oceania, and Africa

In particular, the Asian currency crisis was a critical juncture that drove and even deepened the inter-regional institutions across the Asian region, which has been known as a ‘region without regionalism’ (Hänggi and Rüland 2006, p. 3). In this vein, ASEM, APEC, ASEAN+3, and even FEALAC have emerged and/or been reshaped by this external threat that the region-level assessed.

The third type of inter-regionalism encompasses the relations between groupings and single powers. The main actors are Europe, US, and China. In particular, China has been actively approaching so-called third world groups including Latin America and Africa, for the purpose of meeting its interests, namely, natural resources (Lee 2016, pp. 185–188). However, China has paid little attention to the internal affairs of its counterpart regional member countries.

Thus, these inter/trans-regional forums may be considered a novelty in international relations. They seem to have contributed to a marked differentiation of international relations, constituting components of a fledging multi-layered system of global governance (Hänggi 2000, p. 6). Particularly from the perspective of existing IR theory, inter-regionalism is a representative and/or ‘agora’ that takes place in combining the structural or neorealist approach to IR (Kenneth 1979) with interdependence theory (Keohane and Nye 2012). As stated above, cooperative balancing transpires at the global level via the inter-regional system.

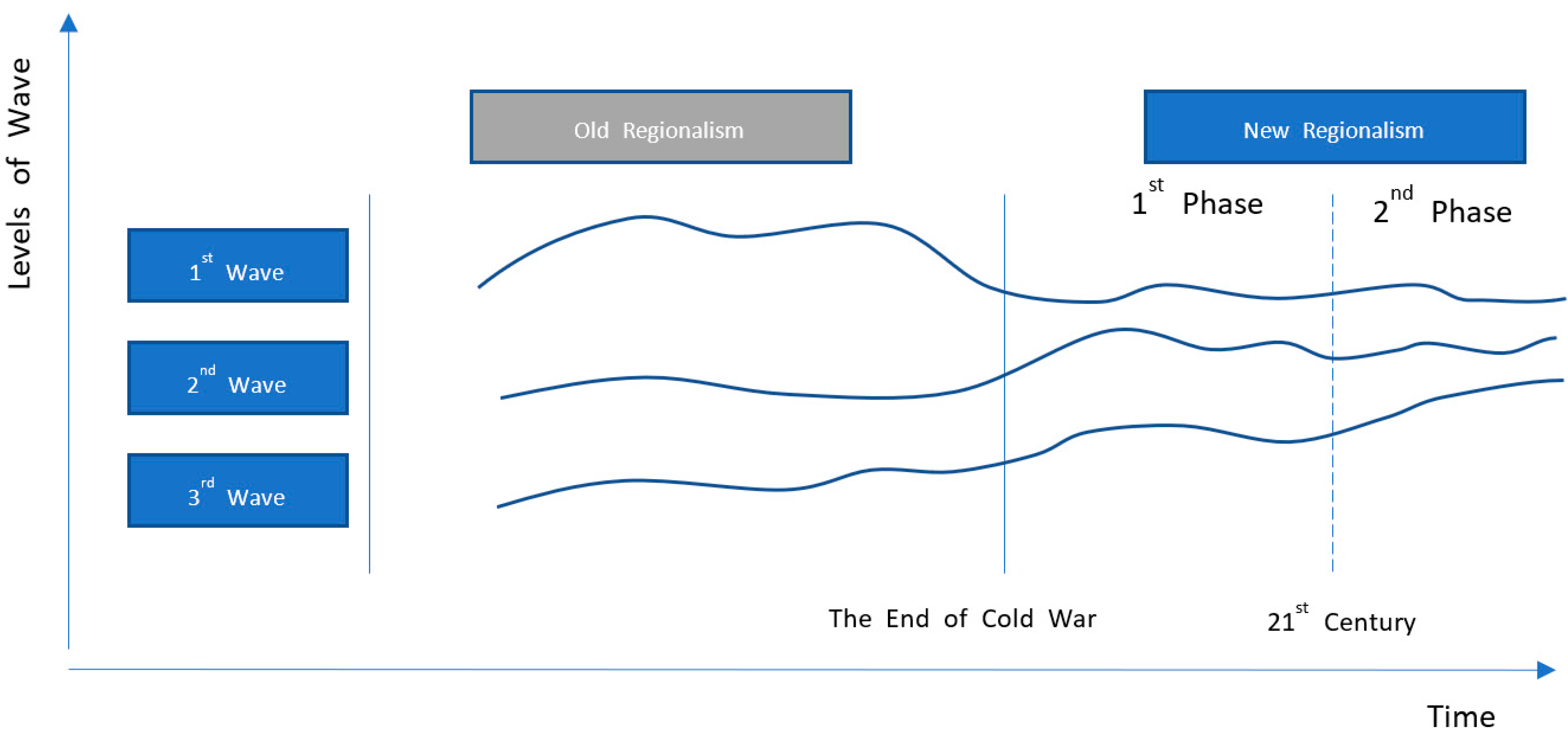

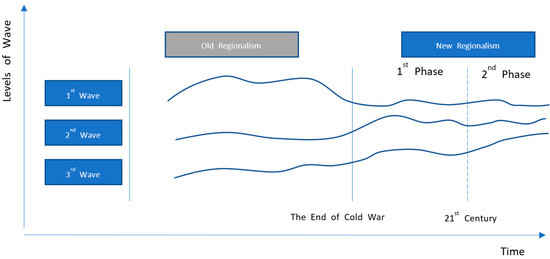

Overall, Figure 1 demonstrates that the waves of regionalism have been based on distinctive features. As studied above, inter-regionalism has also taken place over the era of old regionalism, with special reference to the hub–spoke system by EC. To reiterate, it has been mainly ‘in-Triad’ or ‘Triad + periphery.’ However, one of the features that this study paid attention to is ‘the periphery + periphery’ inter-regional cooperation over the 21st century. In this regard, FEALAC, arguably, is considered to fit into this category.

Figure 1.

Waves of Regionalism according to bifurcated reflection on regionalism. Source: Author’s compilation from existing regionalism studies. Note: The height of wave demonstrates the representation and/or popularity of regional institutions. It is not meant for comparison among the waves, but rather, to showing the flows and tendencies of the characteristics of regionalism.

Under the umbrella of the old regionalism, three waves existed. However, as shown in Figure 1, the first wave is the most salient feature in the old regionalism. Subsequently, in the 1990s, as we have discussed, new regionalism replaces old regionalism by providing more nuances and explanations for the surge of regional institutions at that time. Over this period, inter-regional governance took place more intensively, particularly at the start of the 21st century. This new regional architecture understands cooperation through inter-regional aspects and attempts to embrace globalism through inter-relationships, providing room for changing its institutional features.

To reiterate, one feature that this study takes seriously is the second phase of new inter-regionalism, which primarily began in the 21st century. In the initial period, one salient feature is the non-Triad relational regionalism. In other words, the Global South–South cooperation has appeared. It has been mainly ‘in-Triad’ or ‘Triad + periphery.’ However, one of the features that requires attention is ‘the periphery + periphery’ inter-regional cooperation over the 21st century. In this line of argument, FEALAC fits into this category.8

3. Five Systemic Functions and FEALAC

As a non-Triad entity, FEALAC provides an example of inter-regionalism that can be analyzed through its five systemic functions, based on both rationalist (including realism and neoliberal institutionalism) and reflectivist (social constructivism) perspectives. These critical actions for successful inter-regionalism include (1) balancing, (2) institution-building, (3) rationalizing decision-making in global multilateral forums, (4) agenda setting, and (5) collective identity building. The next section will explore these functions of inter-regionalism as applied to ASEM and EU-ASEAN dialogues (Rüland 1999; Rüland 2001, pp. 19–20) and will use this conceptualization to analyze FEALAC.

3.1. Balancing

Balancing the various functions of inter-regionalism involves two interconnected factors (Doidge 2014, p. 37). These can be classified as internal-oriented and external-led balancing rationales. In short, the former involves the idea that nation-states pursue their own interest given the neorealist perspective, which is a world of self-help. Thus, it could be interpreted as a self-focused component of balancing which leads to diversification of trade relationships as a means of reducing dependence on particular markets (Faust 2004, p. 747; Doidge 2014, p. 42). Under the framework of inter-regionalism, there is room for maneuvering for nation-states to meet their national interests—politically, economically, and culturally. The latter factor functions as a ‘sign’ for external actors and other institutions, including the EU, APEC, and ASEM. In other words, inter-regional institutions are a mechanism for constraining other actors or ensuring their open and honest participation within the global multilateral architecture (Doidge 2014, p. 42). In this sense, Faust (2004) analyzed the inter-relationship between Latin America and Asia, from a Latin American perspective. The reason why Latin America intends to expand its relationship with Asia, particularly circa the 2000s, is closely related to the argument presented here with respect to the self-focused component of balancing. This aspect also coincides with Asia’s point of view, especially Japan,9 China,10 and Korea,11 among others, so as to diversify its relationship beyond western countries. In the sense of nation-state interests embedded in the balancing mechanism, there are largely three distinctive and, at the same time, inter-related factors that led to the formation of FEALAC for the purpose of counter-balancing features. This is a more rationalist explanation than that of the constructivist approach.

In this aforementioned sense, first, the rationale behind FEALAC was as a response to the external threat of the Asian Financial Crisis (Paz 2018, p. 167). It started in Thailand and had repercussions all the way to Brazil, but only western countries escaped its impact. Thus, in this explanation, a sense of economic threat was embedded, giving momentum to the search for balancing behind FEALAC, which emerged as an inter-regional arrangement. Similarly, the ASEM (Asia–Europe Meeting) itself provided an impetus that inspired and encouraged FEALAC (Abad 2010, p. 210). ASEM, established in 1996, may be considered to exert a sort of peer pressure for FEALAC, which was discussed in 1998 and realized afterwards. Thus, the peer pressure can also be counted toward the function of balancing. Furthermore, the emergence of another (sub) regional economic entity, NAFTA, took place in 1994 and also contributed to inciting FEALAC as a multilateral response to prevent unilateral action by a specific power (Doidge 2014, p. 42). Thus, several suitable factors are indicative of balancing as the major rationale behind FEALAC. This stance is largely shown by the very first sentence of the first official Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (FEALAC 2001) document: “Global interdependence is a reality that cannot be ignored. But the global market is highly uneven in its effects and does not in itself create international cohesion” (1st FMM, official document). This aspect is coupled with the notion of ‘cooperative balancing’ (Link 1998). In this sense, the social constructivist approach assumes a significant role as cooperative balancing is deeply ingrained in the notion of inter-subjectivity. In other words, it is based on mutual understanding. This aspect emphasizes that interactions at the inter-regional level are socially constructed. Further elaboration on this point will be provided in the subsequent subsection.

3.2. Institution Building

The rationalist approach, with a special reference to neoliberal institution, has a powerful perspective to shed light on the course of institution building. The institutional process of FEALAC is a mechanism to facilitate cooperation between member states by setting rules, norms, and procedures that promote efficiency and stability in the inter-regional realm. In this vein, while this approach has the power to explicate it, as Rüland (2006) observed, inter-regional entities including FEALAC are still under the auspices of “soft institutionalization”(Rüland 2006, pp. 302–304).

In the realm of institution building, however, this paper views two features as salient. One aspect is the emergence of FEALAC and its maintenance as an informal and less institutionalized entity. At the same time, the diametrically opposite aspect is that FEALAC intends to institutionalize. The rationale behind FEALAC’s commitment to a lower degree of formality is that it adopts an informal and flexible approach to avoid rigid adherence to an institutional blueprint—an approach which was adopted at the very beginning of its inception (Hermawan 2016, p. 194). Furthermore, there is a lack of strong intra-regional organizations (in terms of formality) on each sides of the Pacific region. Thus, FEALAC can benefit and also learn from institution-building mechanisms (Hermawan 2016, p. 196). In this line, the intra-regional legacy may lead to pessimism, particularly with Japan and China emphasizing bilateral relations; the legacy of distrustful relations looms large and shapes the feature of this region, largely due to the colonial legacy and its continuing effects.

However, over the course of the second decade of its establishment, FEALAC has become increasingly institutionalized. As a matter of fact, beginning with the second decade of the 21st century, the global order has been unsettled primarily due to three factors: (1) the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis, which predominantly affected the so-called western world, (2) China’s ‘peaceful’ rise, which has surpassed Japan economically and threatens the United States in several ways, and (3) the annual G20 summit since 2010, which provides room for developed and developing countries to discuss the key global issues and agenda. These three external dynamics have provided impetus for FEALAC to become institutionalized, resulting in a second phase of FEALAC’s development.

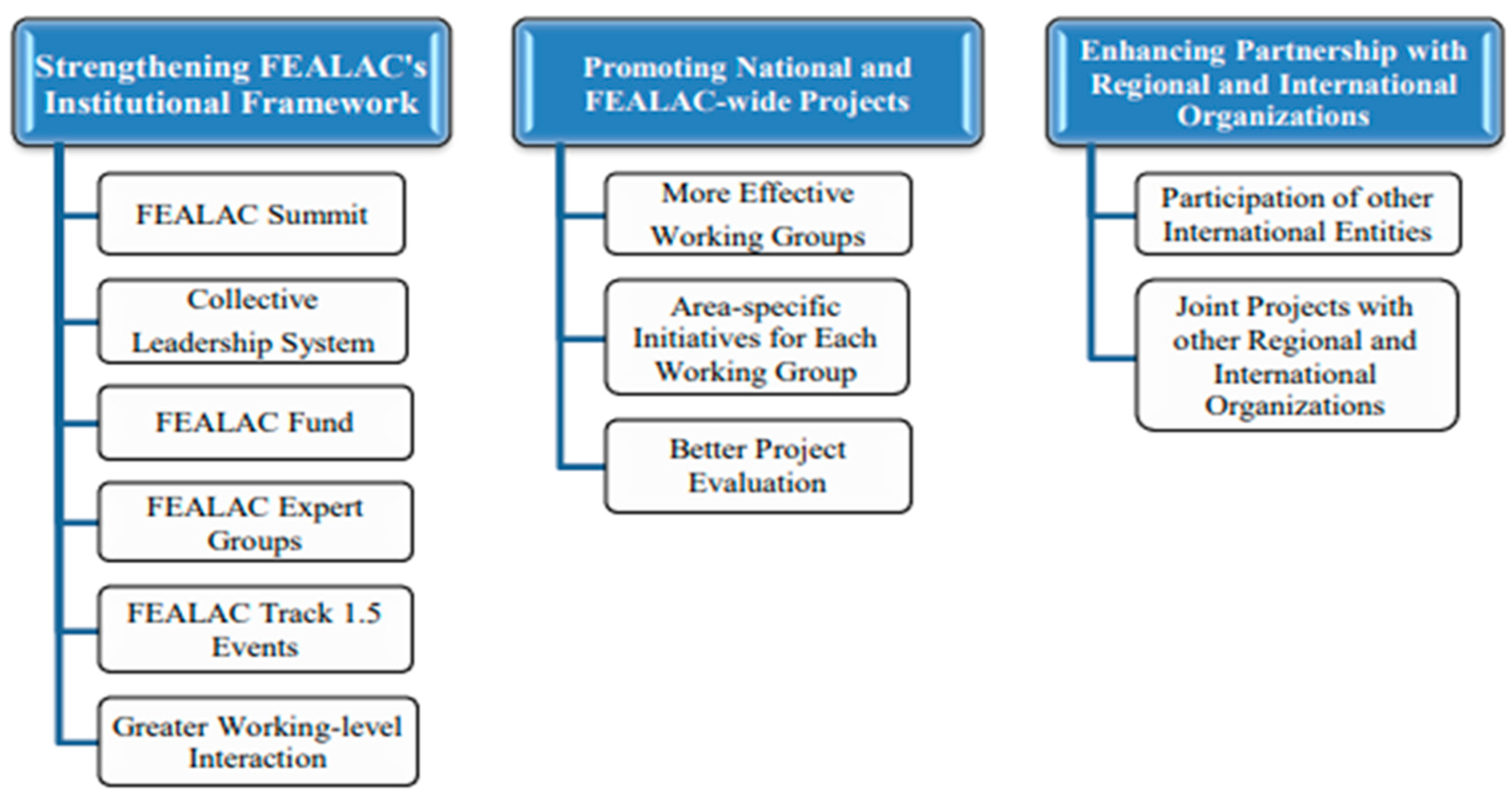

In this aforementioned vein, amongst many others, there are three distinctive institutional processes that took place. First, in 2011, the FEALAC Cyber Secretariat was established in Seoul, South Korea. This institutional mechanism was carried out according to the outcome of the Fourth FMM held in Tokyo in 2010. The significance of having a proper secretariat is that there is an official forum that supports all FEALAC-related activity and can also serve as a think tank for future development. In fact, this Cyber Secretariat as an institutional mechanism can be seen as being located between the APEC and ASEM. In other words, while APEC has its own secretariat in Singapore, ASEM does not have its own proper secretariat.12 Second, the ‘New FEALAC Action Plan’ was proposed for the celebration of the 20th anniversary of FEALAC in 2017, and it is currently in the implementation phase following the planned structure as shown in Figure 2.

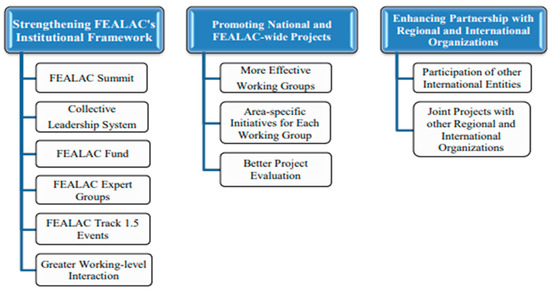

Figure 2.

New FEALAC Action Plan. Source: fealac.org (Annex IV of 7th FMM Declaration Document).

As seen in Figure 2, the New FEALAC Action Plan is composed of three pillars: (1) Strengthening FEALAC’s Institutional Framework, (2) Promoting National and FEALAC-wide Projects, and (3) Enhancing Partnership with Regional and International Organizations. As to whether these plans, which are proposed and decided among member countries, could be deemed successful or not, should be analyzed in a detailed manner. One of the important aspects of this institutional building pillar proposed by the Action Plan is the FEALAC fund, which will be discussed in the following subsection.

Third, the main organs of FEALAC have been changed and further institutionalized to enhance more effective and fruitful relations between two regions through the ‘FEALAC Troika Modality.’ This modality was held on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly, consisting of the previous, current, and incoming Regional Coordinators. This raises the question of how to ensure an effective implementation of mid-to-long-term projects and enhance the predictability of the FEALAC agenda (FEALAC 2019).

3.3. Rationalizing the Decision-Making in the Global Multilateral Forums

According to Hänggi’s explanation, rationalizing with respect to inter-regionalism refers to a process by which “multilateral global forums have to contend with an increasingly complex and technical nature of policy matters and growing number of actors, often representing diverse interests […] inter and trans-regional relations [serve] as clearing house for global forums, streamline the overburdened agenda of global organizations” (Hänggi et al. 2006, p. 11). In a similar vein, Rüland (2006, p. 306) argues that inter-regional dialogue can serve to unlock multilateral gridlocks. This aspect brings the notion of a regional world perspective into play. Acharya elaborates this view, stating that “the rise of [inter-]regionalism could be at least partly attributed to the limitations and weaknesses of global institutions” (Amitav 2018, pp. 109–10). It is a consequence of a system of global governance that increasingly seems to have fallen short of expectations. Thus, the (inter-)regionalism seems to be a rather optimal solution for the multifaceted global agenda in the turbulent global order.

However, regionalism is no panacea for world disorder (Amitav 2018, p. 110), because a different degree of regional organizations exists, when comparing Asia with the African region. Furthermore, the orientation and order of priorities should differ because each region has its own agenda with specific priorities that need to be addressed through region-based institutions. The Asian region possesses significant economic strength, but political mistrust persists among certain Asian countries, including China, Japan, and Korea. This mistrust can be attributed to factors such as colonial legacies, ideological incompatibilities, and the deeply entrenched norm of non-intervention (Amitav 2018, p. 110).

Overall, as discussed previously, the current form of regionalism is often regarded as new regionalism, which is characterized by the open regionalism mechanism. Open regionalism, in this context, is primarily understood as a non-exclusionary form of regionalism. This mechanism serves as a cost-effective approach to rationalize thinking and establish meaningful connections between region-to-region cooperation and trans-regional cooperation in a rational and pragmatic manner. This paper supports the notion that this rationalizing explanation can be considered as an inter-subjective perspective. Member states in inter-regional institutions utilize rational decision-making processes to shape their actions and strategies. They engage in rationalizing their decision-making to ensure coherence and effectiveness within the inter-regional context. In short, rationalizing the decision-making is what member states in the inter-regional dialogues make of it. Through the inter-regional mechanism, member states are willing to actively engage in shaping agendas that will yield mutual benefits in various aspects. Therefore, as they are becoming institutionalized, the member states employ this inter-regional mechanism to satisfy their interests. It is a stance to be learned from agenda setting.

3.4. Agenda Setting

The rationalizing function is closely related to the agenda-setting functions of inter-regional forums (Hänggi et al. 2006, p. 12; Hwee and Vidal 2008). To reiterate, what has garnered the greatest interest from regional actors is the potential contribution that inter-regional structures may offer in addressing the inherent difficulties of large-scale multilateral negotiations and advancing a cooperative agenda at the global level (Doidge 2014, p. 43). In a similar vein, Hwee and Vidal (2008) pointed out that, “Inter-regional forums can reduce the ‘bottleneck effect’ in multilateral negotiations by allowing the various parties to discuss their interests beforehand” (Hwee and Vidal 2008, p. 52). This paper supports the idea that an explanation related to the process of agenda setting focuses on the global agenda. In other words, this inter-regional dialogue serves to filter the global agenda, which functions as a mechanism of ‘pause and go.’ This deductive explanation can be confirmed by empirical cases.

However, there is also a set of specialized agendas at the inter-regional level. All agendas can be discussed at the various levels of meetings, beginning with the working groups (WGs) which specialize in deliberating on which agendas should be taken up and discussed further. In this vein, the most important decision-making mechanism is the Foreign Ministers’ Meeting (FMM), which is the highest authority organ. To reiterate, WGs are entities that meet regularly to present agendas based on their own topics and execute them.

In fact, over the course of a series of meetings (FMM, SOM, WGs), FEALAC has discussed global agendas and implements them in the inter-regional realm. This aspect is largely examined in the FMM declaration documents. Among the nine FMMs held so far, the fourth FMM (held in Japan, which was the 10th anniversary of FEALAC’s founding) undertook to reassess and reemphasize the global issues that can be discussed at the inter-regional level. This Tokyo Declaration underlines the importance of bi-regional cooperation to overcome the global financial crisis, and confirms the need to strengthen cooperation among member countries on climate change, environmental issues, and sustainable development (Fourth FMM Official Document 2010).

In addition, during the ninth Forum of Ministers of Foreign Affairs (FMM), held in the Dominican Republic, ‘climate change’ was incorporated as a new topic to be addressed under the Socio-Political Cooperation and Sustainable Development Working Group. The revamped working group (WG) was adopted at this FMM.13 Hence, apart from following the global agenda, the inter-regional mechanism can also play a role in generating new agendas.

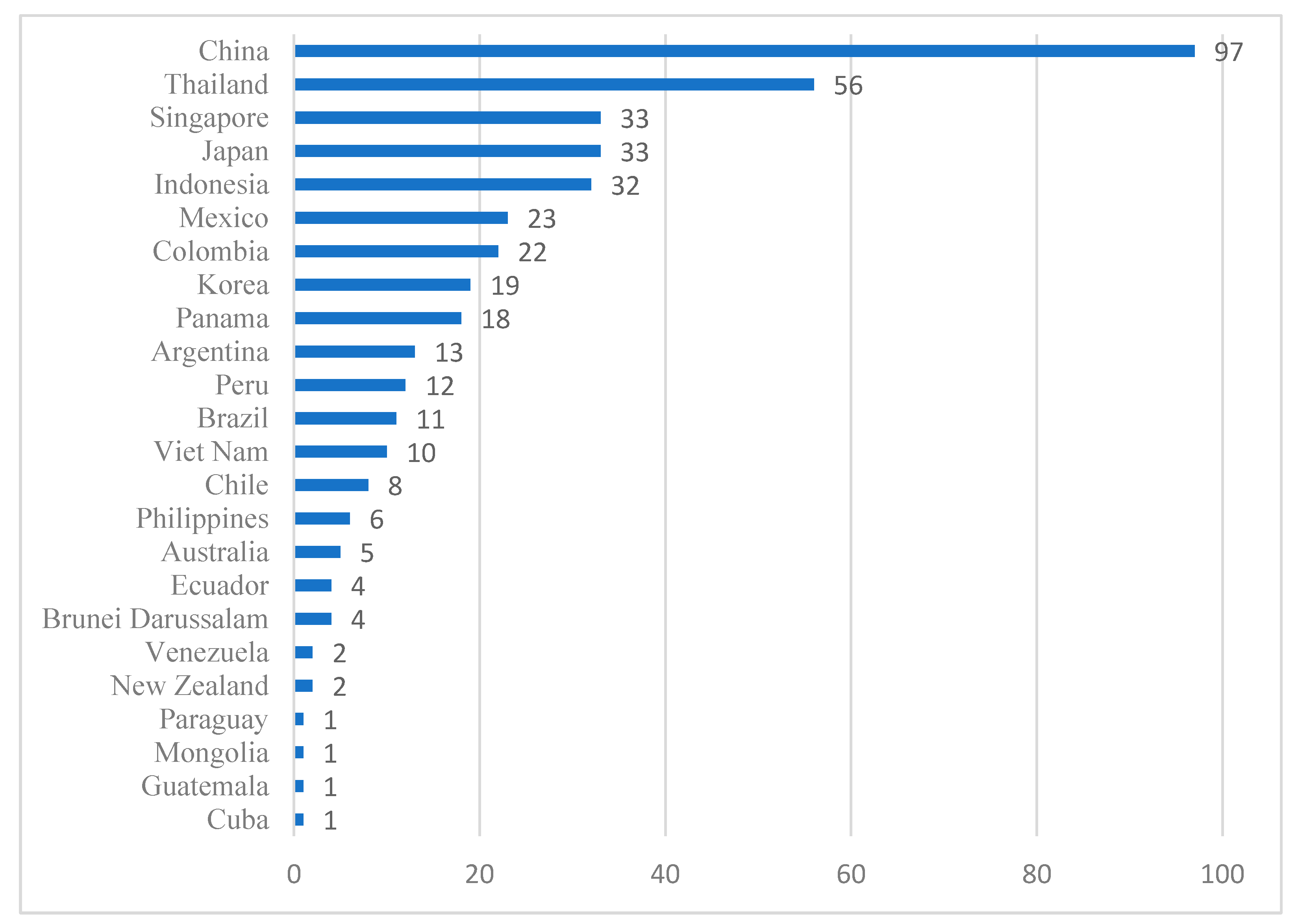

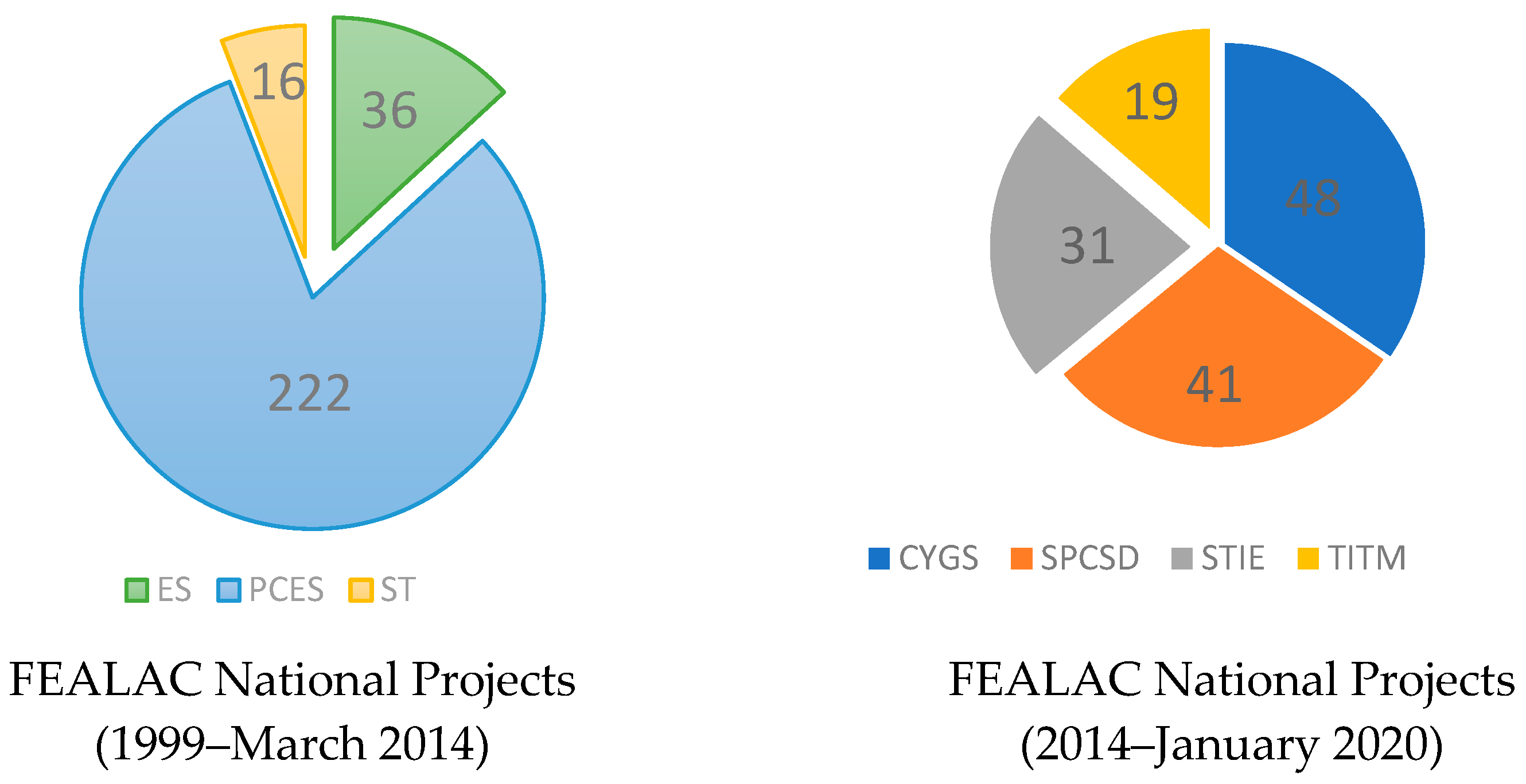

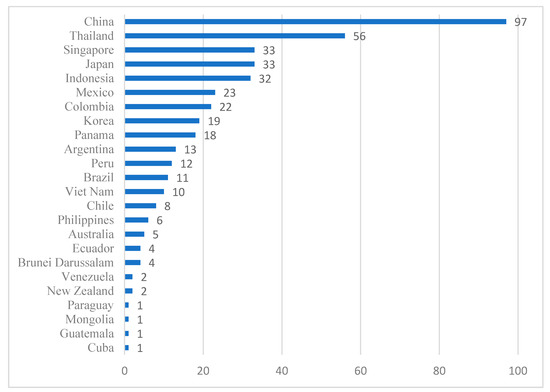

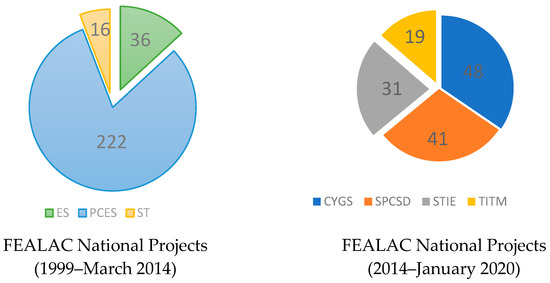

As mentioned, the rationale behind this institution comes into play to fill the gap between the two regions in various ways. As depicted in Figure 3, there have been notable national projects undertaken. Furthermore, Figure 4 illustrates that these projects are executed under the auspices of various working groups (WGs).

Figure 3.

FEALAC National Projects by Country (1999–2020). Source: Author’s calculation from data provided by fealac.org.

Figure 4.

FEALAC National Projects by WGs. Source: Author’s calculation from data provided by fealac.org.

According to Figure 3, it is evident that China (97), Thailand (56), and Singapore (33) in the East Asia region have undertaken a higher number of projects compared to their counterparts. However, it is worth noting that Mexico (23) and Colombia (22), among the Latin American countries, have also implemented their own national projects.

This graph provides an overview of how FEALAC operated in terms of national projects under the two distinct periods of working groups. All national and joint projects are discussed at relevant WG meetings. According to its protocol, all national projects, to some extent, receive recognition at the FMM. Table 2 demonstrates how particular WGs, which are exclusively responsible for agendas, evolve and provide their relevant distinctive contents.

Table 2.

History and Summary of WGs.

Given the different versions of WGs, the evaluation of the effectiveness of WG projects would not be included in the scope of this research. De facto, as stated above, the New FEALAC Action Plan proposed during the eighth Forum of Ministers of Foreign Affairs (FMM) incorporates the second pillar, which focuses on Promoting Effectiveness of Working Groups and Projects. Along with the Vision Group’s recommendation, this aspect has been initiated for implementation. In particular, the FEALAC multi-donor trust fund has been established at the eighth FMM14 and the purpose of this fund is to promote a pan-FEALAC (FEALAC-wide project) in which all FEALAC member countries participate, under the partnership with the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), and the United Nations Economic Commission for Asia and the Pacific (ESCAP). With the establishment of this fund, two FEALAC-wide projects have been implemented, as shown in Table 3 below.

Table 3.

FEALAC-wide projects.

Subsequently, following the modification of the working groups to include the issue of climate change during the ninth Forum of Ministers of Foreign Affairs (FMM), this globally critical issue has been considered from the inception of FEALAC. Starting from the second FMM, every adopted declaration has emphasized the significance of addressing climate change. However, despite this priority, the implementation of climate change initiatives has been limited to a very small number of nationally driven projects. Among the numerous national projects listed in Table 4, only three are directly related to climate change.

Table 4.

Climate Change-Related Projects.

At present, there exists a disparity between the de jure recognition of the climate change issue and the de facto implementation of actions to address it, despite its overwhelming global significance. This gap between rhetoric and action is a key aspect that this paper highlights, emphasizing the need to reshape the orientation and identity of FEALAC to effectively tackle this pressing issue.

3.5. Collective Identity Building

How and in what ways does the FEALAC mechanism shape or enhance this inter-regional building effort that is commonly situated in the Pacific Rim? To a large extent, it seems that (inter-)regional identity has emerged from the relations which are characterized by mutual trust driven by social learning (Higgott 1994; Amitav 1997). According to Adler and Barnett (1998, p. 54).

Learning increases the knowledge that individuals in states have not just about each others’ purposes and intentions but also of each others’ interpretations of society, politics, economics, and culture; to the extent that these interpretations are increasingly shared and disseminated across national borders, the stage has been laid for the development of a regional collective identity.

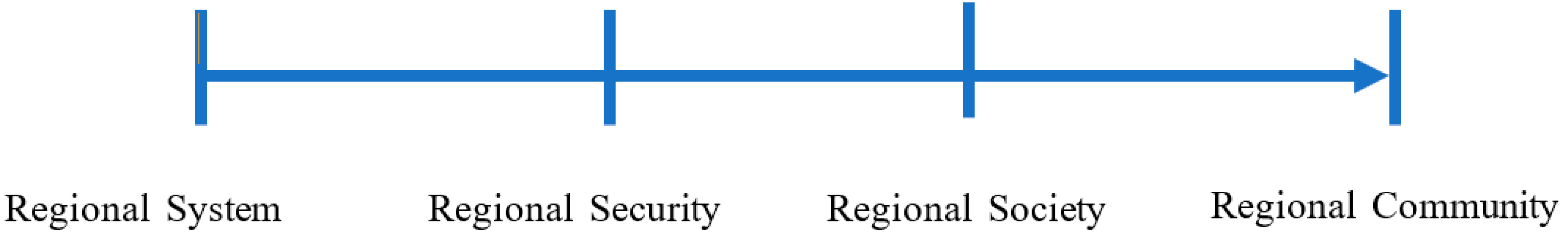

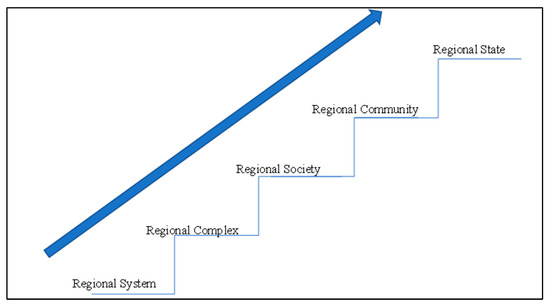

To reiterate, learning is one key aspect in which (inter-)regional institutions help enhance collective identity. This learning aspect is developed through the notion of transactions and communication flows (Checkel 2016, p. 560. In this concept, (inter-)regional collective identity can be differentiated by its stage and degree, based upon the ways this (inter-)region has been inter-related. While Ayoob (1999) classified four distinctive concepts, as shown in Figure 5, Hettne and Söderbaum (2000, pp. 457–73) provide five, as demonstrated in Figure 6. Ayoob (1999) visualized a continuum stretching from regionalism system at one end to regional community at the other, with regional security and regional society lying in between.

Figure 5.

Four levels and scopes of regionalization. Source: Author’s compilation from Mohammed Ayoob.

Figure 6.

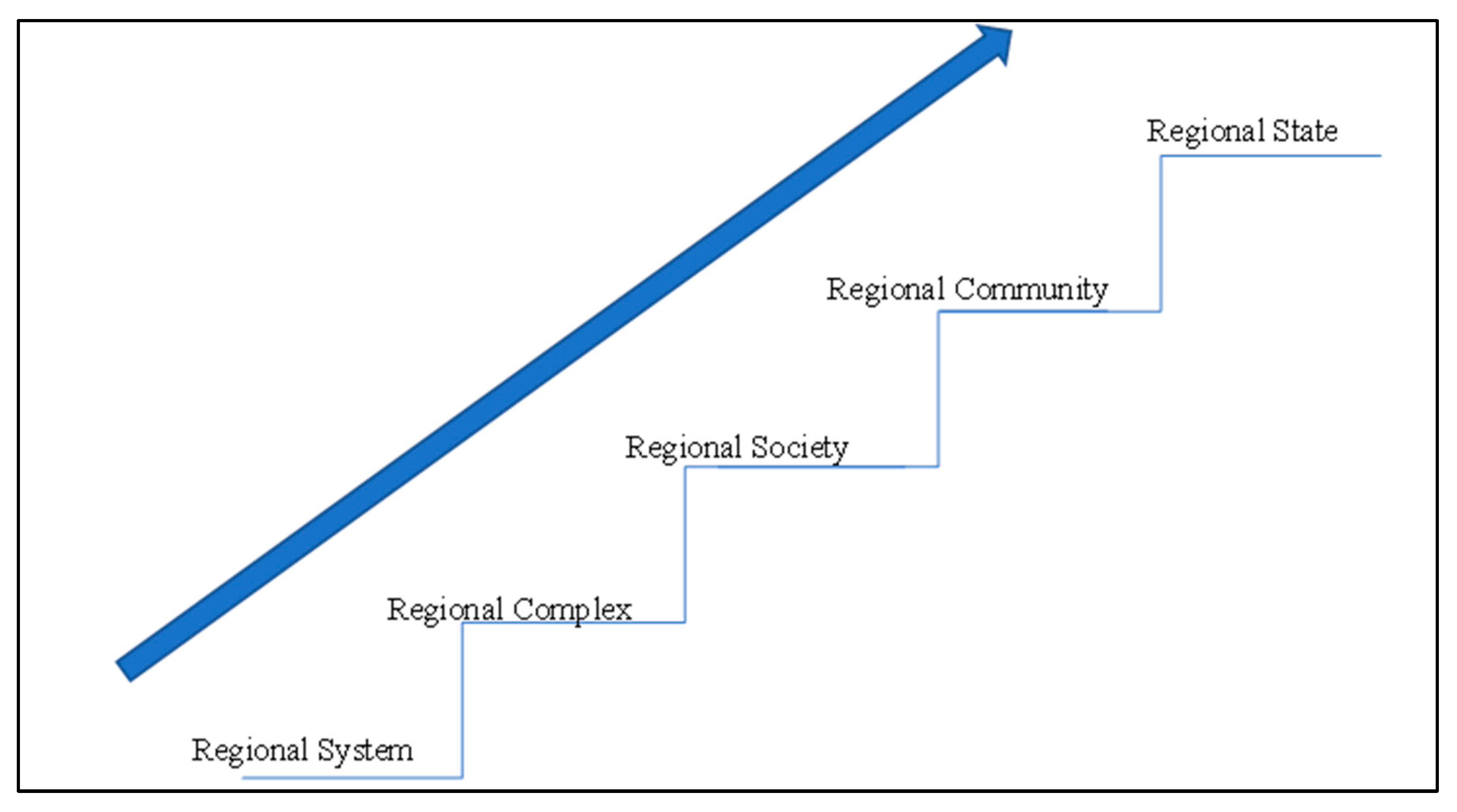

Five Regions: Degree and Scope of regional integration. Source (Hettne and Söderbaum 2000).

Alternatively, Hettne and Söderbaum (2000, pp. 457–73) visualize the stages as follows: regional system, regional complex, regional society, regional community, and regional state.

Subsequently, given these processes and level of regionness, the inquiry proceeds as to which one can locate the (inter-)regional governance with a special reference to FEALAC in the Pacific Rim. As demonstrated above, there have been mutual relations via the FEALAC mechanism. In fact, as Paz (2018) indicated, there are four phases for relations between Asia and Latin America, after the end of the Cold War, which include: (1) the increase in bilateral political dialogue of the 1990s, (2) the Asian Economic Crisis (3) China’s accession to the WTO in 2001, which led to other Asian countries including Korea having the FTA with Chile, and (4) the financial crisis in 2008, which provided an impetus for Asia (particularly China) to form links to Latin America in various ways including FDI. These bi-regional relations contribute to the enhancement of regional identity, a phenomenon that can be better understood through the lens of the social constructivist approach.

In addition to these aspects, as Paz (2018, p. 166) mentioned, the first regular relations between the regions was that of the ‘Galeon de Manila,’15 which started as early as 1565 and lasted for 250 years. While galleons crossed the Pacific, this relation made possible processes of socialization, of learning, and also of identity adaptation as countries of the Pacific. This initial development played a critical role in enhancing the growing network of the Asia–Pacific region, although arguably, there was a certain degree of missing linkage between two regions after the galleons’ voyage. The initial phase of relation was a ‘nutritive element’ for understanding the importance of ideas in identity formation. Inter-regionalism, as an increasingly densely institutionalized structure of region-to-region relations, provides a locus for regularized contact and a venue for socialization. It offers, in short, a framing context for the construction of regional identities and awareness (Higgott 1994).

Subsequently, there has been different phases in which the two regions have become socialized through certain institutions, including FEALAC. As Checkel (2016) explains, the identity shapes institutions and vice versa (Checkel 2016, p. 52). In this regard, the level and extent of both regions can be predominantly characterized as an inter-regional society, as emphasized by scholars such as Ayoob (1999) and Hettne and Söderbaum (2000). Hence, while ‘Region without Regionalism’ is a critique of the (inter-)regional level, compared to the EU, it is understood that there is a certain degree of regionalism that has taken place in this inter-region. Thus, it refers to the notion that inter-regional dialogues may spur collective identities.

Taken together, all five seemingly distinct systemic functions form the basis for analyzing how FELAC fits into the existing knowledge of (inter-)regionalism. Consequently, inter-regionalism represents the third wave of new regionalism, characterized by its own distinctiveness. Rather than being static and top-down, it embodies “soft regionalism” and “flexible consensus,” as demonstrated in the official framework document of FEALAC. Therefore, the process of institutionalization proceeds at a relatively slow pace. While both regions are aligned with this characteristic, as emphasized by Amitav (2018), FEALAC should prioritize the climate issue, as reiterated during the ninth FMM. This pathway to enhancing FEALAC’s role allows it to evolve into a genuine inter-regional actor within the global architecture, akin to the regional worlds proposed by Amitav.

4. Conclusions

This paper demonstrates how inter-regional governance is a key aspect of the global realm. In other words, globalism and regionalism are not mutually exclusive, but rather mutually reinforcing, forming a cohesive system. This is exemplified through the evolution and distinctive characteristics of various waves of regionalism. In this vein, FEALAC, which arguably receives less attention and is less studied, has been taken into account for the purpose of understanding the scope and degree of inter-regional governance. Upon establishing its system, FEALAC presented its orientation, which encompasses the informal and less institutionalized entities. While FEALAC has experienced a gradual process of institutionalization, it has nonetheless made significant progress, particularly during the second decade of its existence, guided by the New FEALAC Action Plan. Following the new plan, the FEALAC Multi-donor Trust Fund has been realized, along with innovation of WGs. This aspect is remarkably significant, as FEALAC assumes a crucial role in shaping the global agenda beyond inter-regionalism. In this context, FEALAC, being predominantly non-Triad, has the potential to transition from a rule-taker to a rule-maker, particularly in addressing the climate change issue. Up to the present, FEALAC has not been effectively and efficiently engaged in the realm of climate change action, although it has recognized its importance in almost all of the FMM official documents. However, the significance of this issue can be further strengthened by the development of the Asia–Pacific Identity, which has evolved through inter-regional dependencies since the early 1500s. This aspect has been examined within the context of the formation of collective regional identity.

In this sense, given that the COVID-19 pandemic is highly related to climate change, there is room for maneuvering by which FEALAC may enhance its awareness and become a truly global actor. This paper suggests that the Pan-FEALAC WAY project, presented by FEALAC, is timely and serves as a flagship initiative. Furthermore, while trade issues are often addressed at the bilateral or (sub-)regional level through various regional entities, it is crucial to address the globally significant aspect at the (inter-)regional level. This has been proved to be more effective and efficient than that of the global approach. In this vein, climate-related issues, which start with the local realm, move to the global one. It is recognized that the most effective way to address these challenges lies within the realm of (inter-)regionalism, surpassing the limitations of the UN system. Therefore, this system is expected to be a defining characteristic of the near future, as we already encounter multifaceted agendas. This approach will be deeply ingrained in the spirit of the 21st century.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (Ministry of Education) of 2018 [NRF-2018S1A6A3A02081030].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) is an inter-governmental forum for 21 member economies in the Pacific Rim. This entity promotes free trade throughout the Asia–Pacific region. APEC started in 1989, in response to the growing interdependence of Asia–Pacific economies. In 1989, in Canberra, Australia, APEC began as an informal ministerial-level dialogue group with 12 founding members. In 1993, in Blake Island, United States, APEC economic leaders met for the first time and outlined APEC’s vision of “stability, security and prosperity for our peoples” (Source: APEC official website). |

| 2 | The Central American Integration System (Sistema de la Integración Centroamericana in Spanish) is the institutional framework of Central American Regional Integration. The cooperation Korea–SICA began with the Korea–SICA summit in 1996. At the first summit, President Kim Young-sam and the heads of five Central American countries agreed to establish the Korea-SICA dialogue council (Source: Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs official website). |

| 3 | The Community of Latin American and the Caribbean States (CELAC) is an intergovernmental mechanism for dialogue and political agreement, which permanently includes thirty-three countries in Latin America and the Caribbean. CELAC aspires to be a unique voice with structured decision-making policy decisions in the political realm and with cooperation in support of regional integration programs (Source: CELAC official website). On July 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping attended the China–Latin America and the Caribbean Summit led in Brasilia. The Meeting adopted a Joint Statement on China–Latin America and the Caribbean Summit in Brasilia, announcing the formal establishment of the China–CELAC Forum (Source: China–CELAC official website). |

| 4 | The Pacific Basin Economic Council (PBEC) was founded in 1967, and is the oldest independent business association to link the economies of the Asia–Pacific region. PBEC is the independent voice of sustainable business and trade across the Pacific–an organization of business leaders seeking access and opportunities. It is completely independent and apolitical (Source: PBEC official website). |

| 5 | The Pacific Economic Cooperation Council (PECC) is a unique tripartite partnership of senior individuals from business and industry, government, academic, and other intellectual circles. All participate in their private capacity and discuss freely current and practical policy issues of the Asia–Pacific region (Source: PECC official website). |

| 6 | As Richard Higgott (1994) pointed out, the emergence of multilateralism in APEC, ARF, and other forums has contributed to the formation of an Asia–Pacific identity that goes beyond mere economic or security aspects and emphasizes networking activities (p. 367). Similarly, Amitav (1997) has described the construction of a regional identity as the Asia–Pacific Way, which has been facilitated by avoiding institutional grand designs and adopting some features of the “ASEAN Way” (p. 319). |

| 7 | The scope of discussion regarding the typology of security studies is beyond the scope of this paper. However, to put it simply, traditional security is related to miliary affairs, whereas non-traditional security comprises a range of human security concerns, including climate, food insecurity, and others. In this sense, Michael Klare (2002) regards traditional security as a threat from abroad, whereas non-traditional security is being regarded as a threat from within (Klare 2002). |

| 8 | By its definition, the Triad refers to EU, US, and Japan. In this vein, triad region means Europe, North America, and East Asia, re-spectively. In this paper although Japan is a member state of FEALAC, most of its member states are global south including the Latin American members. Thus, this paper considers FEALAC as global south entity. In this aspect, Tsardanidis (2010) stated “FEALAC could be considered as ‘peripheral’ transregionalism because it involves primarily lower-medium and small powers of the South which could not alter the main structural pillars of the international system” (Tsardanidis 2010, p. 228). |

| 9 | For example, except Tokyo in Japan, the largest Japanese population live in Brazil. This indicates that Japan is highly interrelated to Latin America, especially Brazil. |

| 10 | See, among others, Lee Taeheok, “China’s One Belt, One Road’ Initiative, Latin America between “Bandwagoning” and “Balancing,” Latin American and Caribbean Studies 36: 109–10. Realizing that China’s going out strategy to sustain its sustainable development, Lee (2017) critically stated that China has accessed to Latin America as a whole to meet its purpose. |

| 11 | To diversify and increase its economic muscle, Korea, having a FTA with Chile, announced to discuss in 1998 and ratified in 2004. |

| 12 | ASEM rather employs ASEF (Asia Europe Foundation) which is a unique standing organization, and it operates infoboard (aseminfoboard.org) so as to demonstrate how ASEM works. ASEF carries out for the strengthening Asia-Europe relations through seminars, workshops, conferences, publications, web portals, grants and public talks (asef.org). |

| 13 | FEALAC’s WGs have been modified at least three times. It started with three WGs: (1) Politics, Culture, Education and Sports [PCES]; (2) Economy and Society [ES]; (3) Science and Technology [ST]. At the 6th FMM (held in Indonesia), WGs were modified to four: (1) Socio-Political Cooperation and Sustainable Development [SPCSD]; (2) Trade, Investment, Tourism, MSMEs [TITM]; (3) Culture, Youth and Gender, Sports [CYGS]; (4) Science and Technology, Innovation, Education [STIE]. And the at the 9th FMM, ‘Climate Change’ has been incorporated into the first WG which was renamed as Socio-Political Cooperation, Sustainable Development, Climate Change. |

| 14 | The FEALAC Multi-donor Trust Fund is the main content of the ‘New Action Plan’ and reflects the results of recognition of the necessity of the fifth, sixth and seventh FMMs. has been approved. In other words, during the fifth FMM, members shared the need for research on the establishment of a fund (Fifth FMM/51), and the establishment of a fund recommended by the Vision Group at the sixth FMM is a way to make a qualitative leap forward in FEALAC (FEALAC Vision Group Final Report: Evaluations and Recommendations: Article 4.3). At the seventh FMM, the establishment of a cooperative system for regular dialogue to establish a fund with international financial institutions was discussed (Seventh FMM/paragraph 48). As such, the multi-donor trust fund was established as a result of the last three FMMs following discussions among FEALAC members. |

| 15 | The Galeon was a type of Spanish ship which starting as early as 1565, began to sail from Acapulco, Mexico, to Manila in the Philippines, establishing a regular trip that lasted until 1815, a duration of 250 years. |

References

- Abad, Garcia. 2010. Non-triadic interregionalism: The Case of FEALAC. In Asia and Latin America: Political, Economic and Multilateral Relations. Edited by Jorn Dosch and Olaf Jacob. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, Emanuel, and Michael Barnett. 1998. Security Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge University, p. 54. [Google Scholar]

- Amitav, Acharya. 1997. Ideas, identity, and institution-building: From the ‘ASEAN way’ to ‘Asia-Pacific way’? The Pacific Review 10: 319–46. [Google Scholar]

- Amitav, Acharya. 2014. Global International Relations (IR) and Regional Worlds: A New Agenda for International Studies. International Studies Quarterly 58: 647–59. [Google Scholar]

- Amitav, Acharya. 2018. The End of American World Order. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Ayoob, Mohammed. 1999. From Regional System to Regional Society: Exploring Key Variables in the Construction of Regional Order. Australian Journal of International Affairs 53: 247–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Checkel, Jeff. 2016. Regional Identities and Communities. In The Oxford Handbook of Comparative Regionalism. Edited by Tanja A. Borzel. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Doidge, Matthew. 2014. Interregionalism and the European Union: Conceptualizing Group-to-Group Relations. In Intersecting Regionalism. Edited by Francis Baert, Tizinia Scaramagli and Fredrick Söderaum. Heidelberg, New York and London: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Faust, Jörg. 2004. Latin America, Chile and East Asia: Policy-Networks and Successful Diversification. Journal of Latin American Studies 36: 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FEALAC. 2001. First FEALAC FMM. Available online: https://www.fealac.org/new/m/document/board_view.do?idx=4&sboard_id=official_documents&sboard_category=fmm&page=1&onepage=9&orderby=A&sort=desc&sboard_01=&sboard_19=&sboard_20=&sboard (accessed on 3 August 2022).

- FEALAC. 2015. FEALAC Guide. Available online: https://www.fealac.org/new/document/board.do?sboard_id=leaflet&onepage=100 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- FEALAC. 2019. FEALAC Guide. Available online: https://www.fealac.org/new/document/board.do?sboard_id=leaflet&onepage=100 (accessed on 5 August 2022).

- Fourth FMM Official Document. 2010. Available online: https://www.fealac.org/new/document/board.do (accessed on 9 August 2022).

- Gamble, Andrew, and Anthony Payne. 1996. Regionalism and World Order. New York: St. Martin’s Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haas, Ernst. 2009. International Integration: The European and the Universal Process. International Organization 15: 366–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hänggi, Heiner. 2000. Interregionalism: Empirical and theoretical perspectives. Paper prepared at Dollars, Democracy and Trade: External Influence on Economic Integration in the Americas, Los Angeles, CA, USA, May 18. [Google Scholar]

- Hänggi, Heiner, Ralf Roloff, and Jurgen Rüland. 2006. Interregionalism: A new phenomenon in international relations. In Interregioanlism and International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hermawan, Yulius. 2016. Institutionalization of interregional cooperation: The case of ASEM and FEALAC. In Institutionalizing East Asia. Edited by Alice D. Ba, Kuik Cheng-Chwee and Sudo Sueo. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hettne, Bjorn, and Fredrik Söderbaum. 2000. Theorizing the rise of regionness. New Political Economy 5: 457–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgott, Richard. 1994. Ideas, identity, and policy coordination in the Asia-Pacific. The Pacific Review 7: 368–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, Stanley. 1966. Obstinate or Obsolete? The Fate of the Nation-State and the Case of Western Europe. Daedalus 95: 862–915. [Google Scholar]

- Hurrell, Andrew. 1995. Explaining the Resurgence of Regionalism in World Politics. International Studies 21: 331–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwee, Lay Yeo, and Lulc Lopez I. Vidal. 2008. Regionalism and Interregionalism in the ASEM Context: Current Dynamics and Theoretical Approaches. Documentos CIDOB (December 2008). Available online: https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/103570/doc_asia_23.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Katzenstein, Peter. 1996. Regionalism in Comparative Perspective. Cooperation and Conflict 31: 123–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kenneth, Waltz. 1979. Theories of International Politics. Reading: Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Keohane, Robert, and Joseph Nye. 2012. Power and Interdependence, 4th ed. Boston: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Klare, Michael. 2002. Resource Wars: The New Landscape of Global Conflict. New York: A Metropolitan Owl Book. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Taeheok. 2016. Dual Identity of Ecuador: The emergence of China and the paradox of the political and economic development of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Revista Asiática de Estudios Iberoamericanos 27: 185–88. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Taeheok. 2017. China‘s ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiative, Latin America between “Bandwagoning” and “Balancing”. Latin American and Caribbean Studies 36: 85–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, Werner. 1998. Die Neuordnung der Weltpolitik. Grundprobleme globaler Politik an der Schwelle zum 21. Jahrhundert. München: Beck. [Google Scholar]

- Mitrany, David. 1948. The Functional Approach to World Organization. International Affairs 24: 350–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paz, Gonzalo. 2018. Remapping Latin America and East Asia Interregional Relations. In Interregionalilsm and the Americas. Edited by Gian Luca Gardini, Simon Koschut and Andreas Falke. Lanham, Boulder, New York and London: Lexington Books, p. 166. [Google Scholar]

- Riggirozzi, Pia, and Diana Tussie. 2012. Reconstructing Regionalism. In The Rise of Post-Hegemonic Regionalism, 1st ed. Edited by Riggirozzi Pia and Diana Tussie. London: Springer, vol. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Rüland, Jürgen. 1999. ASEAN and the European Union: A Bumpy International Relationship, ZEI Discussion Paper C 95. Bonn: Center for European Integration Studies. [Google Scholar]

- Rüland, Jürgen. 2001. The EU as Inter-Regional Actor: The Asia-Europe Meeting (ASEM). Paper presented at International Conference Asia-Europe on the Eve of the 21st Century, Bangkok, Thailand, August 19–20. [Google Scholar]

- Rüland, Jürgen. 2006. Interregionalism: An unfinished agenda. In Interregionalism and International Relations. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 295–313. [Google Scholar]

- Söderbaum, Fredrik. 2015. Early, Old, New and Comparative Regionalism: The Scholarly Development of the Field”, KFG Working Paper, 64 (October 2015). Available online: https://cris.unu.edu/sites/cris.unu.edu/files/Soderbaum-WP-2015.pdf (accessed on 9 June 2022).

- Söderbaum, Fredrik, and Luk Van Langehove. 2006. The EU as a Global Player: The Politics of Interregionalism. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Tsardanidis, Charalambos. 2010. Interregionalism: A comparative analysis of ASEM and FEALAC. In Asia and Latin America: Political, Economic and Multilateral Relations. Edited by Jorn Dosch and Olaf Jacob. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).