Understanding Social Media Dependency, and Uses and Gratifications as a Communication System in the Migration Era: Syrian Refugees in Host Countries as a Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Social Media Use in Crises, Conflicts, and Wars

3. Media System Dependency (MSD), New Media Dependency (NMD), and Social Media Dependency (SMD)

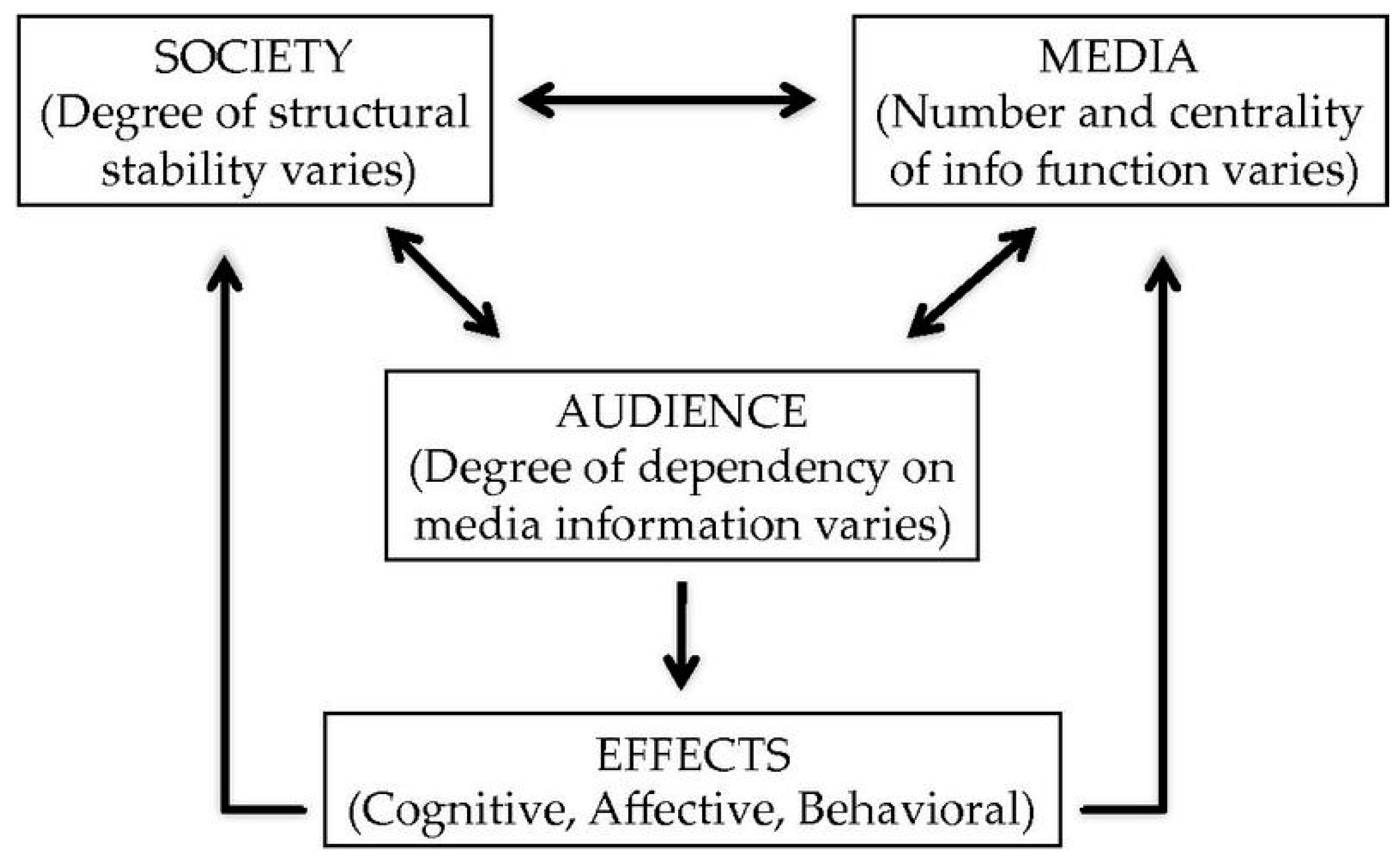

3.1. Media System Dependency (MSD)

3.2. New Media Dependency (NMD) and Social Media Dependency (SMD)

4. Uses and Gratifications Approach (U&G) and Its Application in New Media Apps and Social Media Platforms

4.1. Uses and Gratifications Approach (U&G) Assumptions

4.2. Uses and Gratifications in Mobile Phones, Internet, and Social Media

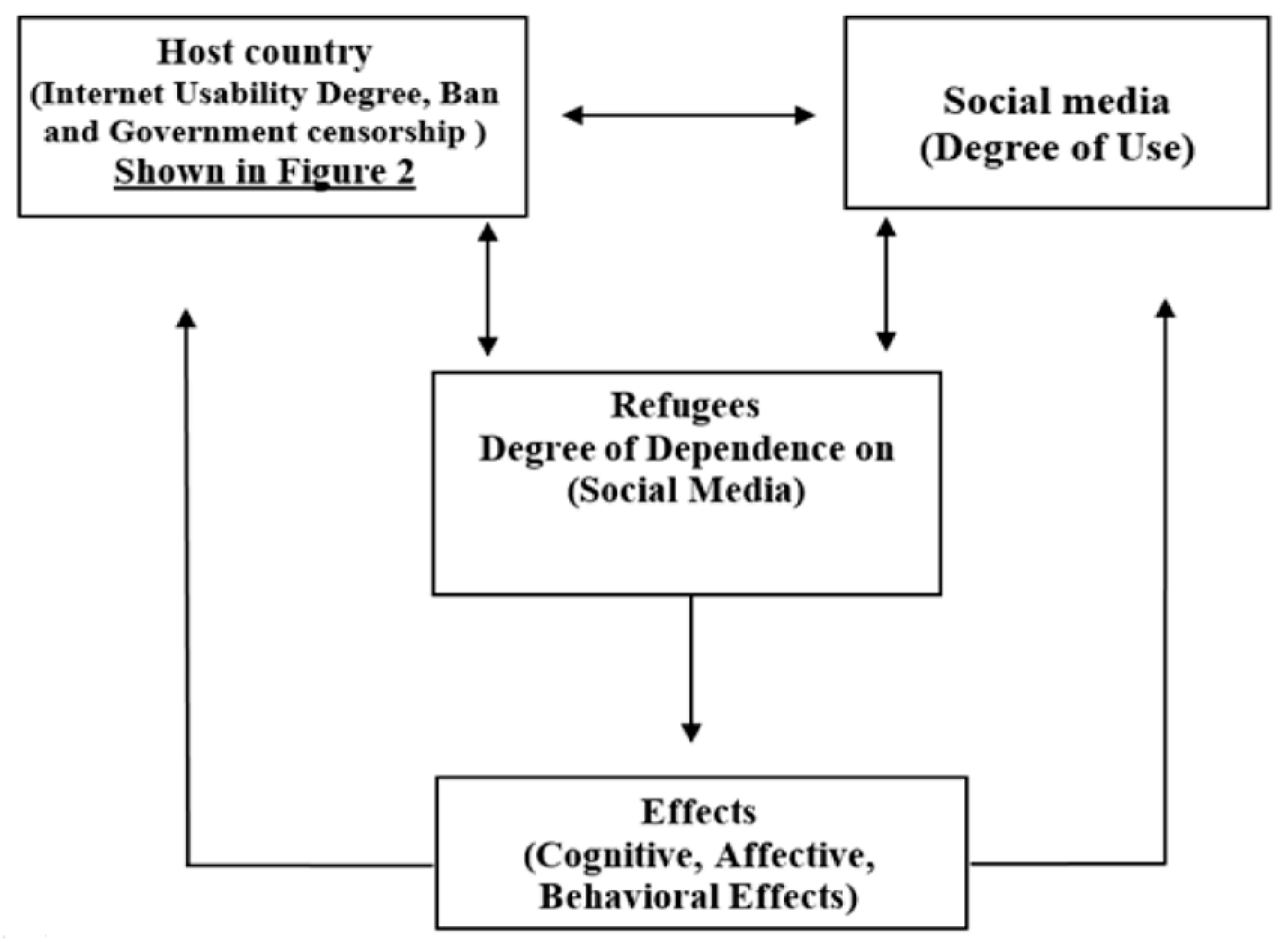

5. Understanding the Syrian Refugees Social Media Use through the MSD Model and the U&G Approach

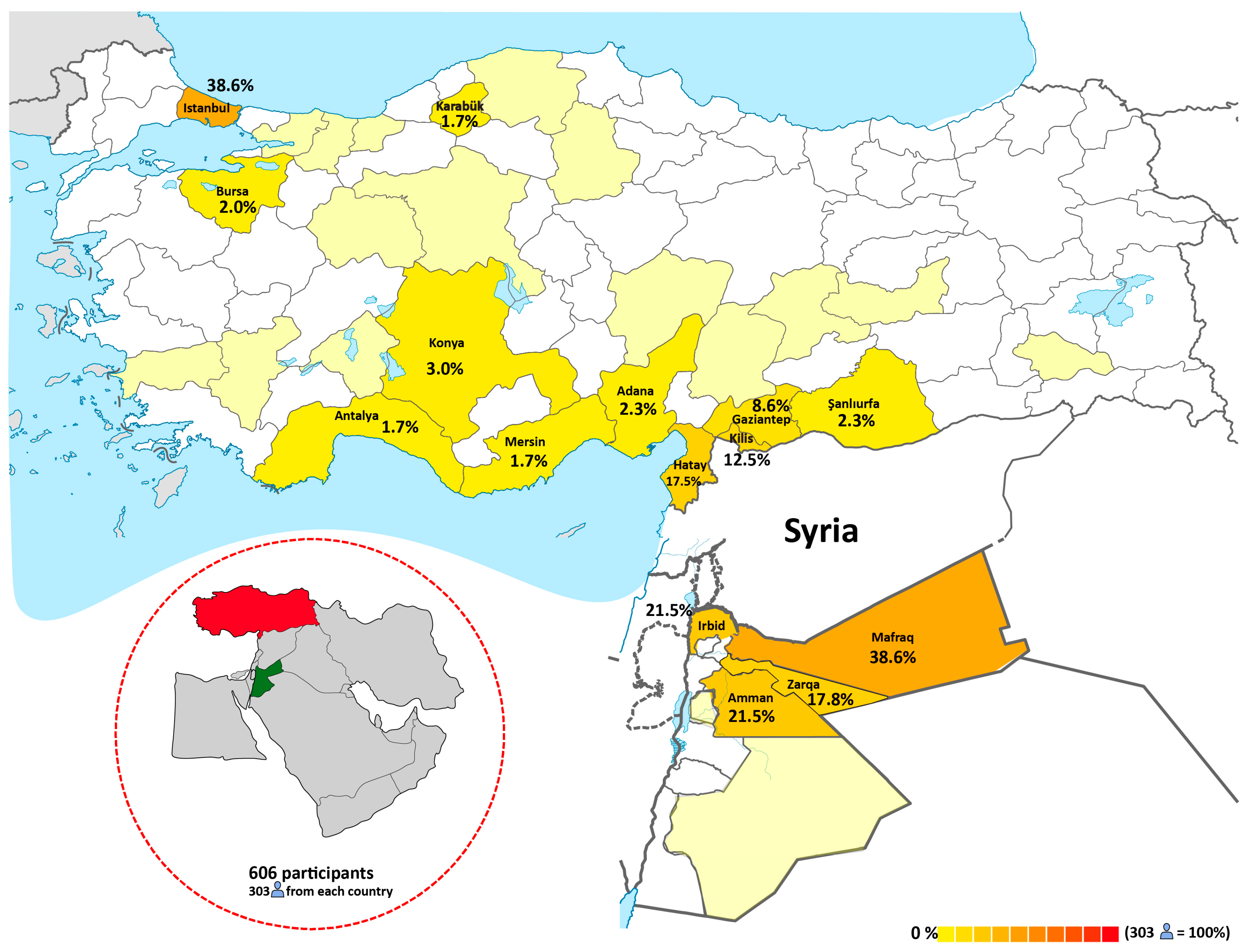

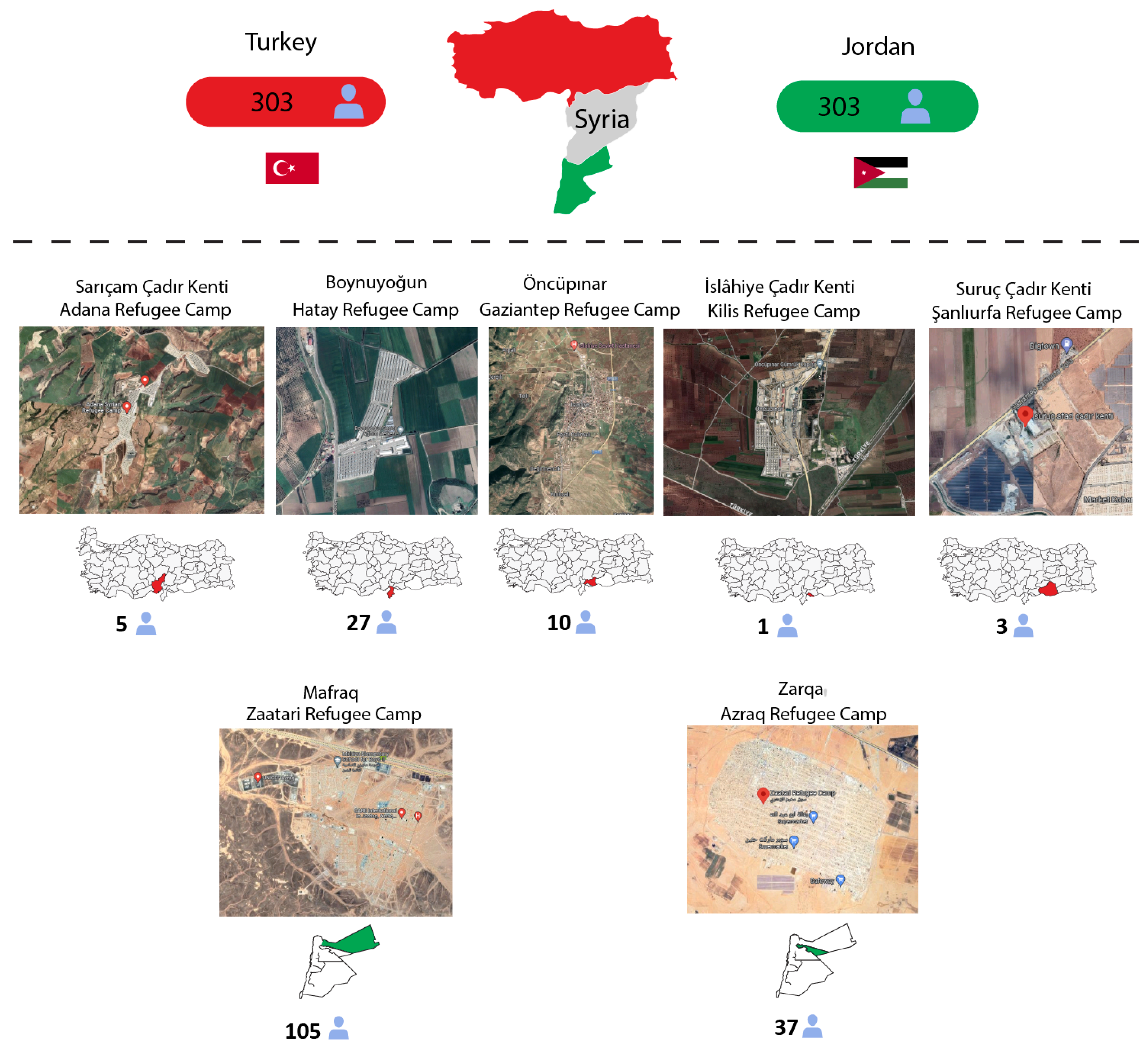

6. Methodological Framework

6.1. Quantitative Method

6.2. Qualitative Method

7. Results and Findings

7.1. The Quantitative Results

7.1.1. The Main Characteristics of the Sample

7.1.2. Social Media Dependency of the Syrian Refugees

7.1.3. Syrian Refugees’ Social Media Uses and Gratifications

7.2. The Qualitative Data

8. Discussion and Analysis of the Findings

8.1. The Increase in Social Media Use among Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Turkey and the Social Media Dependency (SMD)

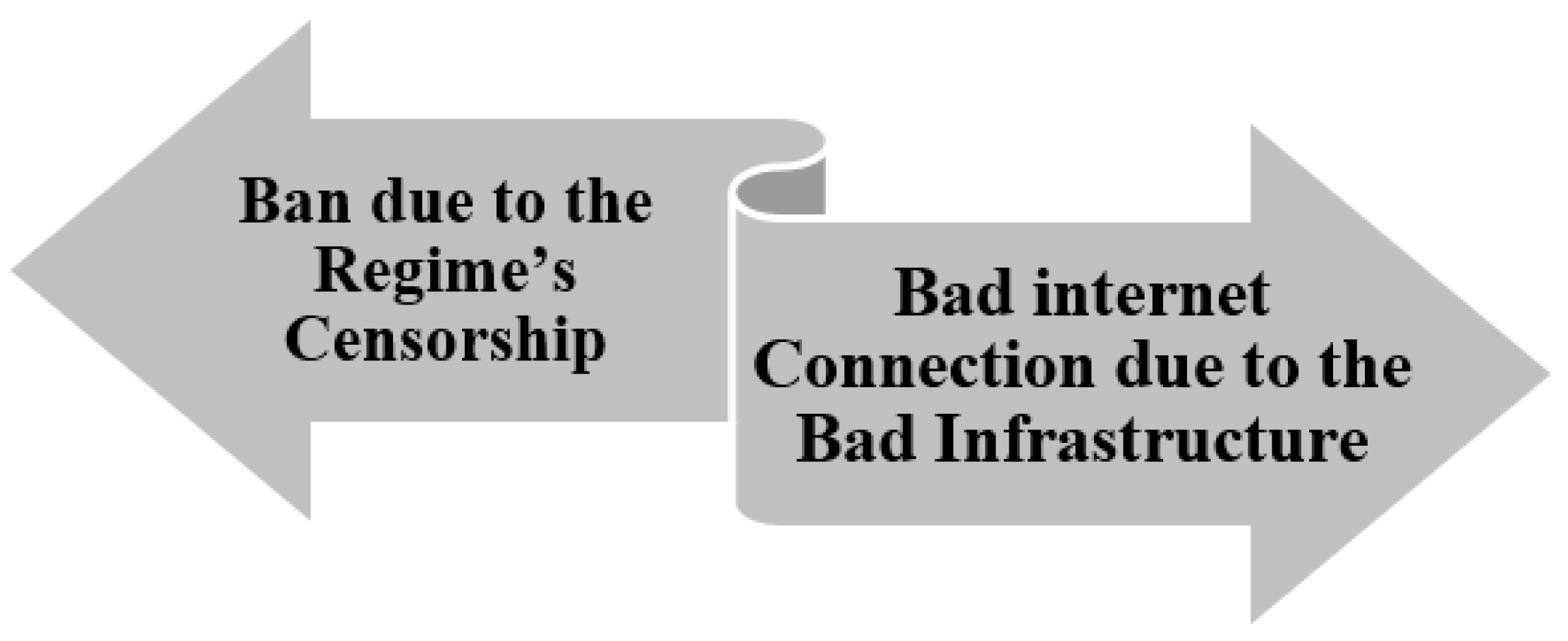

8.1.1. The Increase in Social Media Use among Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Turkey

“The internet was weak and slow in Syria, but here it is fast and available at affordable prices”.(Extract 1, Istanbul Participant 4, Male, 26, Undergraduate student)

“There were restrictions on internet use in Syria, and Facebook was banned due to pressure and security control.”(Extract 5, Amman, Participant 8, Male, 31, Bachelor’s degree/working)

“I had no idea what social media was before because the Internet was not available well in Syria and its speed was slow, but the Internet availability and technological development in Jordan are more advanced than in Syria.”(Extract 2, Amman, Participant 13, Female, 25, College graduate/working)

“I was living in the countryside in Syria; I didn’t have a cell phone and the technology wasn’t advanced. The use of social media was not successful due to the poor quality of the Internet”.(Extract 3, Istanbul, Participant 9, Male, 24, Less than high school education/working)

“There was no freedom in the past. We know that Tal Al-Mallohi, a secondary school student in Homs, was arrested by the Syrian State Security in December 2009 for posting some materials on her blog”.(Extract 4, Istanbul Participant 1, Female, 31, Ph.D. student)

8.1.2. Social Media Dependency (SMD) among Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Turkey

“There were restrictions on internet use in Syria, and Facebook was banned due to pressure and security control.”(Extract 5, Amman, Participant 8, Male, 31, Bachelor’s degree/working)

8.2. The Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among Syrian Refugees

8.2.1. The Commercial, Work, and Business-Based Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among the Syrian Refugees

“After I left Syria, social media has helped me a lot in finding opportunities and networking with organizations and individuals.”(Extract 14, Amman, Participant 1, Female, 30, Graduate student)

8.2.2. The Educational Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among the Syrian Refugees

“Social media has helped me communicate, follow lessons, and get help from my teachers and friends.”(Extract 9, Istanbul, Participant 1, Female, 31, Ph.D. student)

8.2.3. The Entertainment and Leisure-Time-Based Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among the Syrian Refugees

“I have nothing to do in Turkey. I am alone and have neither money nor friends to have fun. But I have fun with social media.”(Extract 6, Istanbul Participant 6, Male, 27, High School graduate/not working)

“I use social media a lot to distract myself from the state of being a refugee and the troubles and difficult conditions I am in. I want to relieve myself of the stress and shortness of breath caused by the war.”(Extract 7, Istanbul Participant 8, Male, 21, Bachelor’s degree/working)

8.2.4. The Self-Expression, Conveying Voices, and Sympathy-Seeking-Based Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among the Syrian Refugees

“Social media was the only window to express the views and know the news of cities and towns that were completely uncovered in the news of the traditional media. If social media platforms were not there, those would be buried in the traditional media.”(Extract 8, Istanbul Participant 3, Female, 35, Master’s degree/not working)

“I’ve been an online activist since the Syria crisis started, and there are a lot of beneficial groups for Syrians on Facebook, and that’s why I started using Facebook here.”(Extract 10, Amman, Participant 15, Male, 32, Graduate student)

8.2.5. The Social Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among Syrian Refugees

“The family broke up, but social media gathered us.”(Extract 12, Istanbul Participant 11, Female, 43, High School graduate/not working)

“Social media was able to connect families and bring people from multiple countries or regions together, despite the distance and difficulty of physiological communication during the revolution. It also expanded the circle with other people.”(Extract 13, Amman, Participant 3, Male, 34, Higher diploma/not working)

“Social media revealed the truth by conveying the suffering of the Syrian people and documenting violations and crimes committed by the regime that are not found in the official media, such as bombing, killing, arresting, displacement, and disclosure.”(Extract 15, Amman, Participant 12, Female, 34, Less than high school graduate/not working)

8.2.6. The Access to Information Uses and Gratifications of Social Media among the Syrian Refugees

“Syrian refugees would not have received the help and aid that were provided if social media did not convey the conditions of the Syrian revolution.”(Extract 11, Istanbul, Participant 4, Male, 26, Undergraduate student)

“Social media platforms focused on some people’s success stories, and it has had a nice effect on them.”(Extract 15, Amman, Participant 2, Male, 33, Undergraduate/Working)

9. Conclusions

10. Limitations and Future Research

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2017. The Role of Print and Electronic Media in the Defense of Human Rights: A Jordanian Perspective. Jordan Journal of Social Sciences 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2023a. Can a Negative Representation of Refugees in Social Media Lead to Compassion Fatigue? An Analysis of the Perspectives of a Sample of Syrian Refugees in Jordan and Turkey. Journalism and Media 4: 90–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldamen, Yasmin. 2023b. Xenophobia and Hate Speech towards Refugees on Social Media: Reinforcing Causes, Negative Effects, Defense and Response Mechanisms against That Speech. Societies 13: 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Dulaimi, Mohammed. 2021. Recent Young Iraqi Political Participation, Social Media Use, Awareness and Engagement. Munich: Technical University of Munich. [Google Scholar]

- Aléncar, Amanda. 2020. Mobile communication and refugees: An analytical review of academic literature. Sociology Compass 14: e12802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Majdhoub, Fatima Mohammed, and Azizah Hamzah. 2016. Framing the ISIL: A content analysis of the news coverage by CNN and Aljazeera. Malaysian Journal of Communication 32: 335–64. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Rawi, Ahmad, and Shahira Fahmy. 2018. Social media use in the Diaspora: The case of the Syrian community in Italy. In Diaspora and Media in Europe: Migration, Identity, and Integration. Edited by H. Karim and Ahmed Al-Rawi. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 71–96. [Google Scholar]

- Alshwawra, Ahmad. 2021. Syrian Refugees’ Integration Policies in Jordanian Labor Market. Sustainability 13: 7234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Sasha, and Marguerite Daniel. 2020. Refugees and social media in a digital society: How young refugees are using social media and the capabilities it offers in their lives in Norway. The Journal of Community Informatics 16: 26–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, Antonio Diaz, and Bill Doolin. 2016. Information and communication technology and the social inclusion of refugees. Mis Quarterly 40: 405–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bache, Christina. 2020. Challenges to economic integration and social inclusion of Syrian refugees in Turkey. Career Development International 25: 14–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballout, Ghada, Najeeb Al-Shorbaji, Nada Abu-Kishk, Yassir Turki, Wafaa Zeidan, and Akihiro Seita. 2018. UNRWA’s innovative e-Health for 5 million Palestine refugees in the Near East. BMJ Innovations 4: 128–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, Sandra J. 1985. The origins of individual media-system dependency: A sociological framework. Communication Research 12: 485–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball-Rokeach, Sandra J., and Melvin L. DeFleur. 1976. A dependency model of mass-media effects. Communication Research 3: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BBC. 2011. Syria: Unblock Facebook without an Official Announcement. Available online: https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast/2011/02/110209_syria_facebook_ (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Bonds-Raacke, Jennifer, and John Raacke. 2010. MySpace and Facebook: Identifying dimensions of uses and gratifications for friend networking sites. Individual Differences Research 8: 27–33. [Google Scholar]

- Bulbul, Abdullah, Cagri Kaplan, and Salah Haj Ismail. 2018. Social Media based Analysis of Refugees in Turkey. Paper presented at the BroDyn: First Workshop on Analysis of Broad Dynamic Topics over Social Media @ ECIR 2018, Grenoble, France, March 26; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar]

- Charmarkeh, Houssein. 2012. Social media usage, tahriib (migration), and settlement among Somali refugees in France. Refuge 29: 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Gina Masullo. 2011. Tweet this: A uses and gratifications perspective on how active Twitter use gratifies a need to connect with others. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 755–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Yoonwhan. 2009. New Media Uses and Dependency Effect Model: Exploring the Relationship between New Media Use Habit, Dependency Relation, and Possible Outcomes. Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate School-New Brunswick, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen, Britt, and Ali Khalil. 2021. Reporting conflict from afar: Journalists, social media, communication technologies, and war. Journalism Practice 17: 300–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Alton Y. K., Dion Hoe-Lian Goh, and Chei Sian Lee. 2012. Mobile content contribution and retrieval: An exploratory study using the uses and gratifications paradigm. Information Processing & Management 48: 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, Rianne, and Godfried Engbersen. 2014. How social media transform migrant networks and facilitate migration. Global Networks 14: 401–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekker, Rianne, Godfried Engbersen, Jeanine Klaver, and Hanna Vonk. 2018. Smart refugees: How Syrian asylum migrants use social media information in migration decision-making. Social Media+ Society 4: 2056305118764439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diminescu, Dana. 2020. Researching the connected migrant. In The Sage Handbook of Media and Migration. Edited by Kevin Smets, Koen Leurs, Myria Georgiou, Saskia Witteborn and Radhika Gajjala. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Donohew, Lewis, Leonard Tipton, and Roger Haney. 1978. Analysis of information-seeking strategies. Journalism Quarterly 55: 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltantawy, Nahed, and Julie B. Wiest. 2011. The Arab spring|Social media in the Egyptian revolution: Reconsidering resource mobilization theory. International Journal of Communication 5: 18. [Google Scholar]

- Etzel, Morgan. 2022. New models of the “Good refugee”–bureaucratic expectations of Syrian refugees in Germany. Ethnic and Racial Studies 45: 1115–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillespie, Marie, Souad Osseiran, and Margie Cheesman. 2018. Syrian refugees and the digital passage to Europe: Smartphone infrastructures and affordances. Social Media + Society 4: 2056305118764440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, Greg, Kathleen M. MacQueen, and Emily E. Namey. 2012. Applied Thematic Analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Ha, Louisa, Kisung Yoon, and Xiaoqun Zhang. 2013. Consumption and dependency of social network sites as a news medium: A comparison between college students and general population. Journal of Communication and Media Research 5: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ifinedo, Princely. 2016. Applying uses and gratifications theory and social influence processes to understand students’ pervasive adoption of social networking sites: Perspectives from the Americas. International Journal of Information Management 36: 192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Committee of the Red Cross. 2016. Syria in Focus. Available online: https://www.icrc.org/en/where-we-work/middle-east/Syria (accessed on 7 February 2022).

- Jung, Joo-Young, and Munehito Moro. 2012. Cross-level analysis of social media: Toward the construction of an ecological framework. The Journal of Social Science 73: 53–74. [Google Scholar]

- Katz, Elihu, Jay G. Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch. 1973. Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly 37: 509–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katz, Elihu, Jay G. Blumler, and Michael Gurevitch. 1974. The Uses and Gratifications Approach to Mass Communication. Beverly Hills: Sage Pubns. [Google Scholar]

- Klapp, Orrin Edgar. 1972. Currents of Unrest: An Introduction to Collective Behavior/Orrin E. Klapp. New York: Holt, Rinehart a. Winston, Cop. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, Amanda E., Adrian C. North, and Brody Heritage. 2014. The uses and gratifications of using Facebook music listening applications. Computers in Human Behavior 39: 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kümpel, Anna Sophie, Veronika Karnowski, and Till Keyling. 2015. News sharing in social media: A review of current research on news sharing users, content, and networks. Social Media+ Society 1: 2056305115610141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, Louis, and Ran Wei. 2000. More Than Just Talk on the Move: Uses and Gratifications of the Cellular Phone. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 77: 308–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Beck, Michael, Alan E. Bryman, and Tim Futing Liao. 2004. The Sage Encyclopedia of Social Science Research Methods. Newcastle upon Tyne: Sage, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Yang. 2008. Media dependency theory. In Encyclopedia of Political Communication. Edited by Lynda Lee Kaid and Christina Holtz-Bacha. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Malik, Aqdas, Amandeep Dhir, and Marko Nieminen. 2016. Uses and gratifications of digital photo sharing on Facebook. Telematics and Informatics 33: 129–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancini, Tiziana, Federica Sibilla, Dimitris Argiropoulos, Michele Rossi, and Marina Everri. 2019. The opportunities and risks of mobile phones for refugees’ experience: A scoping review. PLoS ONE 14: e0225684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matei, Sorin Adam. 2010. Can Media System Dependency Account for Social Media? Or Should Communication Infrastructure Theory Take Care of It? Available online: https://matei.org/ithink/2010/07/27/from-media-dependency-system-to-communication-infrastructure-theory/ (accessed on 17 March 2022).

- McQuail, Denis. 1972. The television audience: A revised perspective. In Sociology of mass Comunications. Edited by Denis McQuail, Jay G. Blumler and Joseph R. Brown. Penguin Modern Sociology Readings. Harmondsworth: England Penguin, pp. 135–65. [Google Scholar]

- McQuail, Denis. 2010. McQuail’s Mass Communication Theory. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 420–30. ISBN 978-1849202923. [Google Scholar]

- Menon, Devadas. 2022. Updating ‘Stories’ on social media and its relationships to contextual age and narcissism: A tale of three platforms–WhatsApp, Instagram and Facebook. Heliyon 8: e09412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammad, Rohullah, and Yasmin Aldamen. 2023. Media dependency, uses and gratifications, and knowledge gap in online learning during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Afghanistan and Turkey. Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies 13: e202324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narli, Nilüfer. 2018. Life, Connectivity and Integration of Syrian Refugees in Turkey: Surviving through a Smartphone. Questions de Communication 33: 269–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- News 24. 2011. Social Media: Double-Edged Sword in Syria. Available online: https://www.news24.com/news24/SciTech/News/Social-Media-Double-edged-sword-in-Syria-20110713 (accessed on 2 January 2022).

- Obschonka, Martin, Elisabeth Hahn, and Nida ul Habib Bajwa. 2018. Personal agency in newly arrived refugees: The role of personality, entrepreneurial cognitions and intentions, and career adaptability. Journal of Vocational Behavior 105: 173–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oudshoorn, Abe, Sarah Benbow, and Matthew Meyer. 2020. Resettlement of Syrian Refugees in Canada. Journal of International Migration and Integration 21: 893–908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, Namsu, Kerk F. Kee, and Sebastián Valenzuela. 2009. Being immersed in social networking environment: Facebook groups, uses and gratifications, and social outcomes. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 12: 729–33. [Google Scholar]

- Raacke, John, and Jennifer Bonds-Raacke. 2008. MySpace and Facebook: Applying the uses and gratifications theory to exploring friend-networking sites. Cyberpsychology & Behavior 11: 169–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reuters. 2011. Social Media: A Double-Edged Sword in Syria. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-social-media/social-media-a-double-edged-sword-in-syria-idUSTRE76C3DB20110713 (accessed on 7 September 2020).

- Ruangkanjanases, Athapol, Shu-Ling Hsu, Yenchun Jim Wu, Shih-Chih Chen, and Jo-Yu Chang. 2020. What drives continuance intention towards social media? Social influence and identity perspectives. Sustainability 12: 7081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, Alan M. 2009. Uses-and-gratifications perspective on media effects. In Media Effects. Milton Park: Routledge, pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Sabie, Dina, Samar Sabie, Cansu Ekmekcioglu, Yasaman Rohanifar, Fatma Hashim, Steve Easterbrook, and Syed Ishtiaque Ahmed. 2019. Exile within borders: Understanding the limits of the internally displaced people (IDPs) in Iraq. In LIMITS ‘19: Proceedings of the Fifth Workshop on Computing within Limits Conference in Lappeenranta Finland, June 10–11. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholten, Peter, and Frans Van Nispen. 2015. Policy analysis and the “migration crisis”: Introduction. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 17: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selwyn, Neil. 2002. ‘E-stablishing’an inclusive society? Technology, social exclusion and UK government policy making. Journal of Social Policy 31: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, Guosong. 2009. Understanding the appeal of user-generated media: A uses and gratification perspective. Internet Research 19: 7–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwood, Harriet. 2014. Global Refugee Figure Passes 50 m for First Time since Second World War. The Guardian. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jun/20/global-refugee-figure-passes-50-million-unhcr-report (accessed on 20 June 2020).

- Singer, Peter Warren, and Emerson Brooking. 2015. Terror on Twitter: How ISIS Is Taking War to Social Media—and Social Media Is Fighting Back. Popular Science. Available online: https://www.popsci.com/terror-on-twitter-how-isis-is-taking-war-to-social-media/ (accessed on 26 June 2020).

- Social Watch. 2017. Social Degradation in Syria: How the War Impacts on Social Capital, Social Watch News. Syrian Center for Policy Research. Available online: http://www.socialwatch.org/node/17648 (accessed on 28 July 2020).

- Stafford, Thomas F., Marla Royne Stafford, and Lawrence L. Schkade. 2004. Determining uses and gratifications for the Internet. Decision Sciences 35: 259–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Shaojing, Alan M. Rubin, and Paul M. Haridakis. 2008. The role of motivation and media involvement in explaining internet dependency. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 52: 408–31. [Google Scholar]

- Taha, Perjan Hashim, and Marit Sijbrandij. 2021. Gender differences in traumatic experiences, PTSD, and relevant symptoms among the Iraqi internally displaced persons. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 9779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tai, Zixue, and Tao Sun. 2007. Media dependencies in a changing media environment: The case of the 2003 SARS epidemic in China. New Media & Society 9: 987–1009. [Google Scholar]

- Tufekci, Zeynep, and Christopher Wilson. 2012. Social media and the decision to participate in political protest: Observations from Tahrir Square. Journal of Communication 62: 363–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. 2015. Syria Emergency. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/syria-emergency.html (accessed on 27 July 2020).

- UNHCR. 2018. Syria Seven Years on: Timeline of the Syria Crisis. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/ph/13427-seven-years-timeline-syria-crisis.html (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- West, Richard L., Lynn H. Turner, and Gang Zhao. 2010. Introducing Communication Theory: Analysis and Application. New York: McGraw-Hill, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Wissö, Therése, and Margareta Bäck-Wiklund. 2021. Fathering practices in Sweden during the COVID-19: Experiences of Syrian refugee fathers. Frontiers in Sociology 6: 721881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalim, Asli Cennet, and Isok Kim. 2018. Mental health and psychosocial needs of Syrian refugees: A literature review and future directions. Advances in Social Work 18: 833–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| N | Hypothesis |

|---|---|

| H1 | Some factors affected the Syrian refugees’ use of social media before and after seeking refuge and led to an increase in social media dependency after seeking refuge in host countries. |

| H2 | There are differences in what social media platforms Syrian refugees rely on the most and the reasons for that. |

| H3 | The Syrian refugees in Jordan and Turkey have a high level of social media dependency for many gratifications, such as information, social, commercial, educational, and cultural gratifications. |

| # | Facebook Groups In Turkey | Link |

| 1 | Student Community in Turkey | https://www.facebook.com/groups/turkiyedekiogrencitoplulugu/ |

| 2 | International Students Community in Kahramanmaraş | https://www.facebook.com/groups/1429901697319612/ |

| 3 | Community of Syrians in Turkey | https://www.facebook.com/syrian.tr/ |

| 4 | Kahramanmaraş Sutcu Imam University Union | https://www.facebook.com/KSU.Birligi/ |

| 5 | Kırıkhan Syrians Community | https://www.facebook.com/syria.kirikhan |

| 6 | Bu ne? | https://www.facebook.com/groups/452659511553316/ |

| # | Facebook Groups In Jordan | Link |

| 7 | Tagamo Syria | https://www.facebook.com/groups/tagamo3syria/ |

| 8 | Syrians Gathered in Jordan | https://www.facebook.com/Syrians.gathered.in.Jordan/ |

| 9 | Zaa’tari Refugee Camp | https://www.facebook.com/ZaatariCamp/ |

| 10 | Syrian Jordanian Aid | https://www.facebook.com/groups/348669608913195/ |

| Focus Groups Discussion in Istanbul | Focus Groups Discussion in Amman | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | Gender | Age | Marital Status | Education | Gender | Age | Marital Status | Education |

| 1 | Female | 31 | Single | PhD student | Female | 30 | Single | Current graduate student |

| 2 | Female | 21 | Single | Current undergraduate student | Male | 33 | Single | Undergraduate graduate/working |

| 3 | Female | 35 | Single | Current Postgraduate/not working | Male | 34 | Single | High diploma/not working |

| 4 | Male | 26 | Single | Undergraduate student | Female | 29 | Married | Undergraduate/not working |

| 5 | Female | 33 | Single | High school graduate/not working | Male | 45 | Married | High school graduate/working |

| 6 | Male | 27 | Married | High school graduate/not working | Male | 22 | Single | High school graduate/working |

| 7 | Female | 33 | Married | Undergraduate graduate/working | Female | 32 | Married | Undergraduate graduate/working |

| 8 | Male | 21 | Single | Undergraduate graduate/working | Male | 31 | Married | Undergraduate graduate/working |

| 9 | Male | 24 | Married | Less than high school graduate/working | Male | 39 | Married | Undergraduate graduate/working |

| 10 | Male | 33 | Single | Current Master’s degree/working as engineer | Female | 48 | Married | PhD/working |

| 11 | Female | 43 | Married | High school graduate/not working | Male | 19 | Single | Undergraduate student |

| 12 | Male | 22 | Single | High school graduate/not working | Female | 34 | Married | Less than high school graduate/not working |

| 13 | Male | 23 | Single | Current undergraduate/working as a translator | Female | 25 | Single | High school graduate/working |

| 14 | Female | 20 | Married | Less than high school graduate/working | Male | 27 | Single | High school graduate/working |

| 15 | Male | 19 | Single | Undergraduate student | Male | 32 | Single | Graduate student |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wireless (Wi-Fi) | 37 | 12.2% | 94 | 31.0% |

| Internet Subscription | 55 | 18.2% | 24 | 7.9% |

| Both of them | 21 | 6.9% | 53 | 17.5% |

| No Personal Computer | 190 | 62.7% | 132 | 43.6% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wireless (Wi-Fi) | 30 | 9.9% | 116 | 38.3% |

| Internet Subscription | 223 | 73.6% | 67 | 22.1% |

| Both of them | 45 | 14.9% | 119 | 39.3% |

| No Smartphones | 5 | 1.7% | 1 | 0.3% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 184 | 60.70% | 235 | 77.60% |

| No | 32 | 10.60% | 12 | 4.00% |

| No member in the family over the age of 18 | 87 | 28.70% | 56 | 18.50% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number in Jordan | Number in Turkey |

|---|---|---|

| 279 | 292 | |

| Youtube | 101 | 139 |

| 93 | 181 | |

| 95 | 80 | |

| Others: Quora, 9GAG, Flickr, InterPals, ASKfm, Telegram, LinkedIn | 45 | 29 |

| Multiple answers were accepted from each respondent The total is more than 303, so the percentage is not valid in this question | ||

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 262 | 86.5% | 192 | 63.4% | |

| 8 | 2.6% | 54 | 17.8% | |

| Youtube | 6 | 2.0% | 26 | 8.6% |

| 2 | 0.7% | 8 | 2.6% | |

| Others: Quora, 9GAG, Flickr, InterPals, ASKfm, Telegram, LinkedIn | 25 | 8.3% | 22 | 7.3% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| More than 4 h per day | 58 | 19.1% | 95 | 31.4% |

| 2–4 h per day | 83 | 27.4% | 109 | 36.0% |

| Less than 2 h per day | 162 | 53.5% | 99 | 32.7% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 223 | 73.6% | 263 | 86.8% |

| No | 80 | 26.4% | 40 | 13.2% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evet | 253 | 83.5% | 247 | 81.5% |

| Hayır | 50 | 16.5% | 56 | 18.5% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 260 | 85.8% | 241 | 79.5% |

| No | 43 | 14.2% | 62 | 20.5% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 283 | 93.4% | 251 | 82.8% |

| No | 20 | 6.6% | 52 | 17.2% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 75 | 24.8% | 52 | 17.2% |

| No | 101 | 33.3% | 51 | 16.8% |

| I do not have children | 127 | 41.9% | 200 | 66.0% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 81 | 26.7% | 74 | 24.4% |

| No | 222 | 73.3% | 229 | 75.6% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 230 | 75.9% | 217 | 71.6% |

| No | 73 | 24.1% | 86 | 28.4% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 169 | 55.8% | 200 | 66.0% |

| No | 134 | 44.2% | 103 | 34.0% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 263 | 86.8% | 214 | 70.6% |

| No | 40 | 13.2% | 89 | 29.4% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 31 | 10.2% | 24 | 7.9% |

| No | 272 | 89.8% | 279 | 92.1% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 273 | 90.1% | 246 | 81.2% |

| No | 30 | 9.9% | 57 | 18.8% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 240 | 79.2% | 138 | 45.5% |

| No | 63 | 20.8% | 165 | 54.5% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 105 | 34.7% | 76 | 25.1% |

| No | 175 | 57.8% | 220 | 72.6% |

| An attempt was made to reach me | 23 | 7.6% | 7 | 2.3% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 95 | 31.4% | 58 | 19.1% |

| No | 28 | 9.2% | 14 | 4.6% |

| Refused to answer | 5 | 1.7% | 11 | 3.6% |

| Total | 128 | 42.2% | 83 | 27.3% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 4 | 1.3% | 10 | 3.3% |

| No | 287 | 94.7% | 273 | 90.1% |

| Refused to answer | 12 | 4.0% | 20 | 6.6% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Answer | Number and Percentage in Jordan | Number and Percentage in Turkey | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | 178 | 58.7% | 182 | 60.1% |

| No | 125 | 41.3% | 121 | 39.9% |

| Total | 303 | 100% | 303 | 100% |

| Extracts | Codes | Themes |

|---|---|---|

| “The internet was weak and slow in Syria, but here it is fast and available at affordable prices”. (Extract 1, Istanbul Participant 4, Male, 26, Undergraduate student) |

|

|

| “I had no idea what social media was before because the Internet was not available well in Syria or its speed was slow, but the Internet availability and technological development in Jordan are more advanced than in Syria.” (Extract 2, Amman, Participant 13, Female, 25, College graduate/working) |

| |

| “I was living in the countryside in Syria;, I didn’t have a cell phone, and the technology wasn’t advanced. The use of social media was not successful due to the poor quality of the Internet”. (Extract 3, Istanbul, Participant 9, Male, 24, Less than high school education/working) |

| |

| “There was no freedom in the past. We know that Tal Al-Mallohi, a secondary school student in Homs, was arrested by the Syrian State Security in December 2009 for posting some materials on her blog”. (Extract 4, Istanbul Participant 1, Female, 31, PhD. student) |

|

|

| “There were restrictions on internet use in Syria, and Facebook was banned due to pressure and security control.” (Extract 5, Amman, Participant 8, Male, 31, Bachelor’s degree/working) |

| |

| “I have nothing to do in Turkey. I am alone and have neither money nor friends to have fun. But I have fun with social media.” (Extract 6, Istanbul Participant 6, Male, 27, High School graduate/not working) |

|

|

| “I use social media a lot to distract myself from the state of being a refugee and the troubles and difficult conditions I am in. I want to relieve myself of the stress and shortness of breath caused by the war.” (Extract 7, Istanbul Participant 8, Male, 21, Bachelor’s degree/working) |

| |

| “Social media was the only window to express the views and know the news of cities and towns that were completely uncovered in the news of the traditional media. If social media platforms were not there, those would be buried in the traditional media.” (Extract 8, Istanbul Participant 3, Female, 35, Master’s degree/not working) |

|

|

| “Social media has helped me communicate by following lessons and getting help from my teachers and friends.” (Extract 9, Istanbul, Participant 1, Female, 31, PhD student) |

|

|

| “Social media has helped me communicate, follow lessons, and get help from my teachers and friends.” (Extract 9, Istanbul, Participant 1, Female, 31, PhD student) |

|

|

| “Syrian refugees would not have received the help and aid that were provided if social media did not convey the conditions of the Syrian revolution.” (Extract 11, Istanbul, Participant 4, Male, 26, Undergraduate student) |

| |

| “The family broke up, but social media gathered us.” (Extract 12, Istanbul Participant 11, Female, 43, High School graduate/not working) |

|

|

| “Social media was able to connect families and bring people from multiple countries or regions together, despite the distance and difficulty of physiological communication during the revolution. It also expanded the circle with other people” (Extract 13, Amman, Participant 3, Male, 34, Higher Diploma, not working). |

| |

| “After I left Syria, social media has helped me a lot in finding opportunities and networking with organizations and individuals.” (Extract 14, Amman, Participant 1, Female, 30, Graduate student) |

|

|

| “Social media platforms focused on some people’s success stories, and it has had a nice effect on them.” (Extract 15, Amman, Participant 2, Male, 33, Undergraduate/working) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Aldamen, Y. Understanding Social Media Dependency, and Uses and Gratifications as a Communication System in the Migration Era: Syrian Refugees in Host Countries as a Case Study. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060322

Aldamen Y. Understanding Social Media Dependency, and Uses and Gratifications as a Communication System in the Migration Era: Syrian Refugees in Host Countries as a Case Study. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(6):322. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060322

Chicago/Turabian StyleAldamen, Yasmin. 2023. "Understanding Social Media Dependency, and Uses and Gratifications as a Communication System in the Migration Era: Syrian Refugees in Host Countries as a Case Study" Social Sciences 12, no. 6: 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060322

APA StyleAldamen, Y. (2023). Understanding Social Media Dependency, and Uses and Gratifications as a Communication System in the Migration Era: Syrian Refugees in Host Countries as a Case Study. Social Sciences, 12(6), 322. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12060322