Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young Co-Researchers

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Participatory Action Research

“is a collaborative approach in which those typically ‘studied’ are involved as decision makers and co-researchers in some or all stages of the research”.

1.2. Understanding and Recognising Bullying

School bullying is in-person and online behaviour between students within a social network that causes physical, emotional or social harm to targeted students. It is characterized by an imbalance of power that is enabled or inhibited by the social and institutional norms and context of schools and the education system. School bullying implies an absence of effective responses and care towards the target by peers and adults.

1.3. The Present Study

2. The Research Process

2.1. The Exploratory Phase

“There is a strong sense of the school being more than simply a place to receive academic education. There appears to be a degree of pride among students as part of being in the school”.(Staff Participant SP, Female)

“We have an LGBTQ+ committee and an anti-racism group”,(Student Participant (Stu, Female))

“a multi-cultural day, anti-racism club etc.”,(Stu, Female)

“Have students from all over the world”.(Stu, Female)

“The staff are oblivious and just let the one person get away with it Every Single Time. It’s like he gets a slap on the wrist and gets on with life. I don’t want a big scene about it I just want that person to stop it. He sexualises 14-year-old girls and it’s not okay.”.(Stu, Female)

“It’s the society that we’re living in right now in that people are just acting out more and people are like not really caring what’s going on. And not really caring about other people”.(Stu, Male)

“…nested within one another, co-implicating and cohabitating. Yet each retains its own distinct identity, organising logic and emerging patterns”.

“Stitches for snitches is still a popular phrase. We are finding it difficult to become a telling school”.(SP, Female)

“You would get slagged by students if they become aware”.(Stu, Female)

“Most of the girls I think just kind of sit and kind of be quiet.”.(Stu, Female)

“And like if they’re asked a question, they answer.”.(Stu, Female)

“Yeah, but you don’t really like… Not that you don’t engage in the class but it’s mostly like, if a girl tries to be funny, it’s not funny. If a boy is funny, it is funny.”.(Stu, Female)

“There’s a huge culture of not being a rat around here…. I mean, it goes way back you know.”.(SP, Female)

2.2. Recruiting the Co-Researchers and Steering Group

2.3. Deciding the Research Question

“In recent years a great deal has been done to address this issue and will be continued to do so, which is very positive”.(SP, Male)

“the LGBTQ+ group are working very hard to encourage inclusion”.(Co-researcher CR, female)

“I think we should focus on Misogyny or/and Sexism in the school because these issues are very prevalent across the entire school. There are sexism issues concerning both the teachers in the school and the students and I believe that they need to be addressed”(CR, Female)

“…dislike of, contempt for, or prejudice against women”.

“I’ve experienced some gender bullying in the school…. It’s more sort of like how you sort of dress and how you look…. Sometimes they can say very nasty sort of names. Or like they just call you stuff, or maybe talk about you”.(CR, Female)

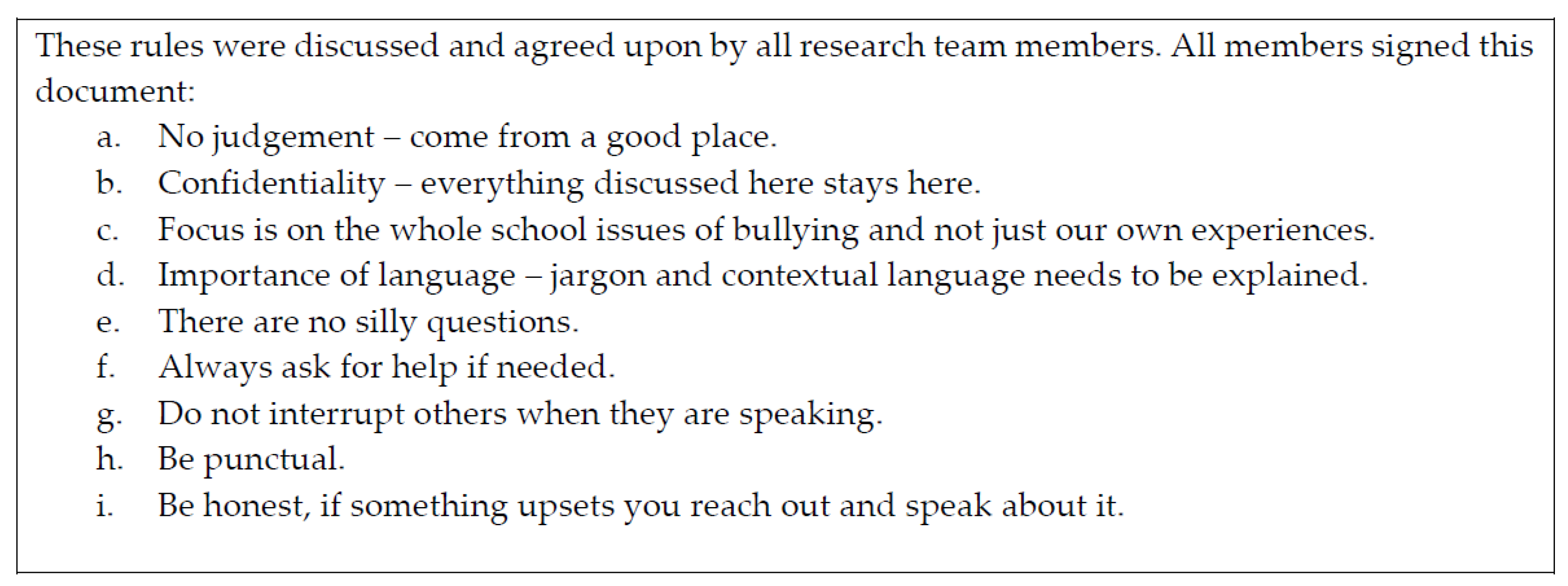

“At yesterday’s meeting, a few of you shared some personal viewpoints and stories so just a reminder of the importance of confidentiality in our sessions (ground rules [Figure 1] that we set at our first meeting) and not sharing other people’s stories outside of our discussions”.(Email 1 March 2022)

“…prejudice or discrimination based on one’s sex or gender. Sexism can affect anyone, but it primarily affects women and girls. It has been linked to stereotypes and gender roles and may include the belief that one’s sex or gender is intrinsically superior to another”.

“And I don’t know, I think that it might be hard for especially some of the boys in our year to decide if it’s like stop as in a joking stop, or stop as in like just stop”.(CR, Female)

“I don’t play rugby anymore but the boy’s rugby team would get new jerseys every year and the girls just don’t ever get rugby jerseys. But then for hockey, it’s similar but like not as bad, not as noticeable as the rugby I think between like boy’s hockey and girl’s hockey”.(CR, Male)

“…. if a school wants to prevent bullying to certain people, vulnerable people. If they want to remove misogynist sayings about women, or even males, they have to push their protocol they have to do every single step. What…is actually getting done? How is it being done? What are the repercussions of this? How are we going to help the bully? How are we going to help the victim?”.(CR, Male)

3. Discussion

- Acknowledging the complexities of power dynamics.

- Understanding time as duration and non-linear.

3.1. Acknowledging the Complexities of Power Dynamics

“…generates different data from adult-to-child enquiry because children observe with different eyes, ask different questions and communicate in fundamentally different ways”.

3.2. Understanding Time as Duration and Non-Linear in the PAR Process 779

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | The latter two to be discussed elsewhere. |

| 2 | The findings from this study will be presented in a future publication. |

References

- Åkerström, Jeanette, and Elinor Brunnberg. 2012. Young people as partners in research: Experiences from an interactive research circle with adolescent girls. Qualitative Research 13: 528–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyon, Yolanda, Bender H. Kennedy, and Jonah Dechants. 2018. A systematic review of Youth Participatory Action Research (YPAR) in the United States: Methodologies, youth osutcomes, and Future Directions. Health Education & Behavior 45: 865–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attawell, Kathy. 2019. Behind the Numbers: Ending School Violence and Bullying. Paris: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Bergström, Jan, Gerhard Andersson, Brjánn Ljótsson, Christian Rück, Sergej Andréewitch, Andreas Karlsson, Per Carlbring, Erik Andersson, and Nils Lindefors. 2010. Internet-versus group-administered cognitive behaviour therapy for panic disorder in a psychiatric setting: A randomised trial. BMC Psychiatry 10: 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradbury-Jones, Caroline, and Julie Taylor. 2015. Engaging with children as co-researchers: Challenges, counter-challenges and solutions. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 18: 161–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Louca-Mai, Lorna Templeton, Paul Toner, Judith Watson, David Evans, Barry Percy-Smith, and Alex Copello. 2018. Involving young people in drug and alcohol research. Drugs and Alcohol Today 18: 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brank, Eve M., Jennifer L. Woolard, Veda E. Brown, Mark Fondacaro, Jennifer L. Luescher, Ramona G. Chinn, and Scott A. Miller. 2007. Will they tell? Weapons reporting by middle-school youth. Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice 5: 125–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2022. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: Avoiding common problems and be (com) ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health 24: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brydon-Miller, Mary, Michael Kral, and Alfredo Ortiz Aragón. 2020. Participatory Action Research: International Perspectives and Practices. International Review of Qualitative Research 13: 103–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, Alan. 2004. Social Research Methods, 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press, p. 592. [Google Scholar]

- Cahill, Caitlin. 2007a. Doing research with young people: Participatory research and the rituals of collective work. Children’s Geographies 5: 297–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, Caitlin. 2007b. The personal is political: Developing new subjectivities through Participatory Action Research. Gender, Place & Culture 14: 267–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camino, Linda. 2005. Pitfalls and promising practices of youth–adult partnerships: An evaluator’s reflections. Journal of Community Psychology 33: 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chabot, Cathy, Jean A. Shoveller, Grace Spencer, and Joy L. Johnson. 2012. Ethical and Epistemological Insights: A Case Study of Participatory Action Research with Young People. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics 7: 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colebrook, Claire. 2002. Understanding Deleuze. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin. [Google Scholar]

- Cooke, Bill, and Uma Kothari, eds. 2001. Participation: The New Tyranny? London: Zed Books. [Google Scholar]

- Cuadrado-Gordillo, Isabel. 2012. Repetition, power imbalance, and intentionality: Do these criteria conform to teenagers’ perception of bullying? A role-based analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 27: 1889–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dadswell, Anna, and Niamh O’Brien. 2021. Working with Adolescents to Understand Bullying and Self-Exclusion from School. International Journal of Developmental Sciences 14: 63–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus. Mineapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ditch the Label. 2020. The Annual Bullying Survey 2020. Available online: https://www.ditchthelabel.org/research-papers/the-annual-bullying-survey-2020/ (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- Eriksen, Tine L. M., Helena S. Nielsen, and Marianne Simonsen. 2018. Bullying in Elementary School. The Journal of Human Resources 49: 839–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Institute for Gender Equality. 2021. What Is Sexism? Available online: https://eige.europa.eu/publications/sexism-at-work-handbook/part-1-understand/what-sexism (accessed on 30 January 2022).

- Evans, Caroline B., and Paul R. Smokowski. 2016. Theoretical explanations for bullying in school: How ecological processes propagate perpetration and victimization. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal 33: 365–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fenwick, Tara. 2012. Complexity science and professional learning for collaboration: A critical reconsideration of possibilities and limitations. Journal of Education and Work 25: 141–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamada, Shoko, Hitoshi Kaneko, Masayoshi Ogura, Aya Yamawaki, Junko Maezono, Lauri Sillanmäki, and Shuji Honjo. 2018. Association between bullying behavior, perceived school safety, and self-cutting: A Japanese population-based school survey. Child and Adolescent Mental Health 23: 141–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart Barnett, Juliet E., Kim W. Fisher, Natasha O’Connell, and Kimberlee Franco. 2019. Promoting upstander behavior to address bullying in schools. Middle School Journal 50: 6–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellström, Lisa, and Adrian Lundberg. 2020. Understanding bullying from young people’s perspectives: An exploratory study. Educational Research 62: 414–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herr, Kathryn, and Gary L. Anderson. 2005. The Action Research Dissertation: A Guide for Students and Faculty. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, Christina, and Kurt W. Fischer. 2008. Research schools: Grounding research in educational practice. Mind, Brain, and Education 2: 157–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horgan, Deirdre. 2017. Child Participatory research methods: Attempts to go ‘deeper’. Childhood 24: 245–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, Paul. 2011. School Bullying and Social and Moral Orders. Children & Society 25: 268–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, Jenny, and Jaimee Stuart. 2020. Do research definitions of bullying capture the experiences and understandings of young people? A qualitative investigation into the characteristics of bullying behaviour. International Journal of Bullying Prevention 2: 180–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellett, Mary. 2010. Small Shoes, Big Steps! Empowering Children as Active Researchers. American Journal of Community Psychology 46: 195–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, Tina, and Debbie Kralik. 2009. Participatory Action Research in Health Care. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, Kurt. 1946. Action Research and Minority Problems. Journal of Social Issues 2: 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linstead, Stephen, and Torkild Tharem. 2007. Multiplicity, Virtuality & Organization: The Contribution of Gilles Deleuze. Organizational Studies 28: 1483–501. [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, Anne M., Jacqueline Celemencki, and Melissa Calixte. 2014. Youth participatory action research and school improvement: The missing voices of black youth in Montreal. Canadian Journal of Education 37: 283–307. [Google Scholar]

- Lundy, Laura. 2018. In defence of tokenism? Implementing children’s right to participate in collective decision-making. Childhood 25: 340–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lushey, Clare J., and Emily R. Munro. 2015. Participatory peer research methodology: An effective method for obtaining young people’s perspectives on transitions from care to adulthood? Qualitative Social Work 14: 522–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manchester, Helen, and Emma Pett. 2015. Teenage Kicks: Exploring cultural value from a youth perspective. Cultural Trends 24: 223–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, Jennifer. 2002. Qualitative Researching, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Mayall, Berry. 2000. The Sociology of Childhood in Relation to Children’s Rights. The International Journal of Children’s Rights 8: 243–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNiff, Jean, and Jack Whitehead. 2011. All You Need to Know about Action Research, 2nd ed. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Meinck, Sabine, Julian Fraillon, and Rolf Strietholt. 2022. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Education: International Evidence from the Responses to Educational Disruption Survey (REDS). Paris: UNESCO. [Google Scholar]

- Merves, Marni L., Caryn R. Rodgers, Ellen J. Silver, Jamie H. Sclafane, and Laurie J. Bauman. 2015. Engaging and sustaining adolescents in Community-Based Participatory Research: Structuring a youth-friendly CBPR environment. Family & Community Health 38: 22. [Google Scholar]

- Migliaccio, Todd, and Juliana Raskauskas. 2016. Bullying as a Social Experience: Social Factors, Prevention and Intervention. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mitra, Dana L. 2009. Collaborating with students: Building youth-adult partnerships in schools. American Journal of Education 115: 407–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohan, Greta, Selina McCoy, Eamonn Carroll, Georgiana Mihut, Seán Lyons, and Ciarán Mac Domhnaill. 2020. Learning for All? Second-Level Education in Ireland During COVID-19. Survey and Statistical Report Series (ESRI) Number 92. Dublin: ESRI. [Google Scholar]

- Nyman, Anneli, Stina Rutberg, Margareta Lilja, and Gunilla Isaksson. 2022. The Process of using Participatory Action research when trying out an ICT solution in home based rehabilitation. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 21: 16094069221084791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Niamh. 2016. To ‘Snitch’ or Not to ‘Snitch’? Using PAR to Explore Bullying in a Private Day and Boarding School. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis, Anglia Ruskin University, Chelmsford, UK. Available online: http://arro.anglia.ac.uk/700970/ (accessed on 2 February 2023).

- O’Brien, Niamh. 2021. School Factors with a Focus on Boarding Schools. In The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Bullying: A Comprehensive and International Review of Research and Intervention. Edited by P. K. Smith and J. O’Higgins Norman. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Niamh, and Audrey Doyle. 2023. Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young co-Researchers. Paper presented at the 7th World Conference on Qualitative Research, Faro, Portugal, January 25–27. [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Niamh, and Tina Moules. 2007. So round the spiral again: A reflective particpatory research project with children and young people. Educational Action Research 15: 385–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Niamh, and Tina Moules. 2012. Not sticks and stones but tweets and texts: Findings from a national cyberbullying project. Pastoral Care: An International Journal of Personal, Social and Emotional Development 31: 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Niamh, Carol Munn-Giddings, and Tina Moules. 2018. The Ethics of Involving Young People Directly in the Research Process. Childhood Remixed, 115–28. Available online: https://www.uos.ac.uk/sites/default/files/Childhood%20Remixed_Journal_2018%20updated.pdf (accessed on 16 February 2023).

- O’Higgins Norman, J., Christian Berger, Christophe Cornu, Donna Cross, Magnus Loftsson, Dorte Marie Sondergaard, Elizabethe Payne, and Shoko Yoneyama. 2021. Presenting a Proposed Revised Definition of School Bullying. Stockholm: World Anti-Bullying Forum & UNESCO. Paris: Ministère de l’éducation Nationale, de la Jeunesse et des Sports. [Google Scholar]

- Olweus, Dan. 2013. School Bullying: Development and Some Important Challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 9: 752–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozer, Emily J., and Laura Douglas. 2015. Assessing the key processes of youth-led participatory research: Psychometric analysis and application of an observational rating scale. Youth & Society 47: 29–50. [Google Scholar]

- Patten, Mildred. 2016. Questionnaire Research: A Practical Guide. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Percy-Smith, Barry. 2012. Exploring the role of children and young people as agents of change in sustainable community development. The International Journal of Justice and Sustainability 18: 323–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resnick, Lauren B. 2010. Nested Learning Systems for the Thinking Curriculum. Educational Researcher 39: 183–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reynaert, Didier, Maria Bouverne-de-Bie, and Stijn Vandevelde. 2009. A Review of Children’s Rights Literature Since the Adopton of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Childhood 16: 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwartz, Amy Ellen, Leanna Stiefel, and Michah W. Rothbart. 2016. Do top dogs rule in middle school? Evidence on bullying, safety, and belonging. American Educational Research Journal 53: 1450–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, William R. 2008. Approaching adulthood: The maturing of institutional theory. Theory and Society 37: 427–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamrova, Daria P., and Cristy E. Cummings. 2017. Participatory action research (PAR) with children and youth: An integrative review of methodology and PAR outcomes for participants, organizations, and communities. Children and Youth Services Review 81: 400–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skelton, Tracey. 2008. Research with children and young people: Exploring the tensions between ethics, competence and participation. Children’s Geographies 6: 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slattery, Lindsey. 2019. Defining the word bullying: Inconsistencies and lack of clarity among current definitions. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth 63: 227–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slonje, Robert, and Peter K. Smith. 2008. Cyberbullying: Another main type of bullying? Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 49: 147–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, Spyros. 2011. The limits of children’s voices: From authenticity to critical, reflexive representation. Childhood 18: 151–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoudt, Brett G., Peter Kuriloff, Michael C. Reichert, and Sharon M. Ravitch. 2010. Educating for Hegeony, Researching for Change: Collaborating with Teachers and Students to Examine Bullying at an Elite Private School. In Class Privilege & Education Advantage. Edited by Adam Howard and Ruben A. Gaztambide-Fernandez. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield, pp. 31–53. [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, Robert, and Hanna Delby. 2019. How do secondary school students explain bullying? Educational Research 61: 142–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tofteng, Ditte, and Mette Bladt. 2020. ‘Upturned participation’ and youth work: Using a Critical Utopian Action Research approach to foster engagement. Educational Action Research 28: 112–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillancourt, Tracy, Patricia McDougall, Shelley Hymel, Amanda Krygsman, Jessie Miller, Kelley Stiver, and Clinton Davis. 2008. Bullying: Are researchers and children/youth talking about the same thing? International Journal of Behavioral Development 32: 502–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaughn, Lisa M., and Farrah Jacquez. 2020. Participatory Research Methods: Choice Points in the Research Process. Journal of Participatory Research Methods 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, Christine. 1989. Action Research: Philosophy, methods and personal experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing 14: 403–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia. 2022. Misogyny. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Misogyny (accessed on 30 January 2023).

- Wójcik, Małgorzata, and Krzysztof Rzeńca. 2021. Disclosing or hiding bullying victimization: A grounded theory study from former victims’ point of view. School Mental Health 13: 808–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younan, Ben. 2019. A systematic review of bullying definitions: How definition and format affect study outcome. Journal of Aggression, Conflict and Peace Research 11: 109–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

O’Brien, N.; Doyle, A. Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young Co-Researchers. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050276

O’Brien N, Doyle A. Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young Co-Researchers. Social Sciences. 2023; 12(5):276. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050276

Chicago/Turabian StyleO’Brien, Niamh, and Audrey Doyle. 2023. "Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young Co-Researchers" Social Sciences 12, no. 5: 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050276

APA StyleO’Brien, N., & Doyle, A. (2023). Exploring School Bullying: Designing the Research Question with Young Co-Researchers. Social Sciences, 12(5), 276. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci12050276