Abstract

Sydney, the capital of the Australian state of New South Wales, is geographically divided by socio-economic conditions and urban opportunities. However, the division in Sydney has not been investigated from an urban planning perspective. This research hypothesises that the urban planning system and its practice-produced consequences promote inequalities in Sydney. This study conceptualises Sydney’s urban inequality in the context of critical concepts of neoliberalism, the theory of power, and the right to the city. Based on semi-structured interviews, secondary documents, and data analysis, this research claims that residents of lower socio-economic areas lag behind compared to others. The paper emphasises the significance of a just city and strong community engagement to reduce the disparate urban policy practices that influence urban divides in Sydney.

1. Introduction

Cities worldwide have been experiencing increasing growth and transformations. Urban growth, development, and socio-demographic evolution present challenges for metropolitan regions and do not always result in increased affluence or bliss for all residents (Frantzeskaki et al. 2022). Instead, it is a process that every so often enforces division in cities, regions, and communities and widens existing disparities between rich and poor (Olajide et al. 2018). Growing inequality in the city has become a significant concern (Davidson and Arman 2014). However, a city’s physical structures do not create urban inequality. Rather, urban planning principles, practices, and regulations produce situations that promote gaps among residents and regions in metropolises (Hyötyläinen 2019). Cities have been transformed into constrained communities in which urban settings separate peoples and places (Olajide et al. 2018; Trounstine 2023). Access to urban amenities and public services becomes increasingly limited for disadvantaged regions. Numerous scholars across a period of one hundred years have used the term ‘cities within a city’ to explain the disparities that exist in the provision of intra-urban infrastructure and urban inequalities in cities (Iveson 2013; Marcuse 1989). This paper discovers the urban inequalities in Sydney, Australia’s largest and most global city, as representing an example of ‘cities within a city’ and critically explores its existing geographical inequalities.

The populations of Australia’s major cities have continued to increase with the growth of the country’s population (Freestone and Pinnegar 2021). Frantzeskaki et al. (2022) claimed that ‘Australia is a nation of cities and towns.’ Consequently, urban planning approaches in Australia have continued to change and develop to reflect urban progress, expansion, and economic movement (Gibson et al. 2022; Ruming and Gurran 2014). Exclusion, residential differentiation, and access to urban prospects have worsened and become increasingly harsh, despite widespread economic growth (Forster 2006). The urban society of Australia has long been moving towards heightened socio-economic disparity (Pusey and Wilson 2003), and Australia’s market-focused strategy has formed splits in metropolises (Freestone and Hamnett 2017). Such traits are also prevalent in other territories, not only in underdeveloped countries, such as Africa (Obeng-Odoom 2015), but also in developed countries, such as Finland (Hyötyläinen 2019) and the UK and the USA (Taylor 2021). The geographical inequalities and socio-economic divides in urban opportunities, resources, and amenities also exist in the global city, Sydney, the New South Wales (NSW) state capital (Taylor 2021).

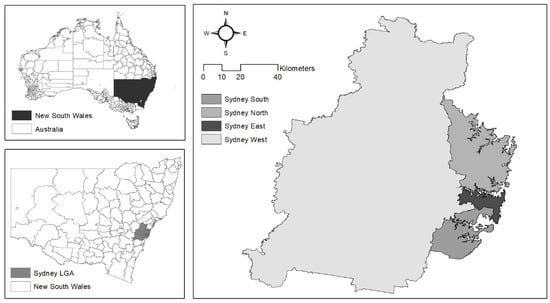

Sydney is one of Australia’s leading and most dense cities. The Sydney metropolitan area, also known as Greater Sydney, comprises a zone of 12,368 square kilometres, a population of 5.3 million people, and 33 local councils or local government areas (LGAs). This research allocates Sydney into four geographical subregions, i.e., east, west, north, and south (Figure 1), based on generally recognised geographical position and demographical features.

Figure 1.

Four subregions in Greater Sydney. Source: authors’ own.

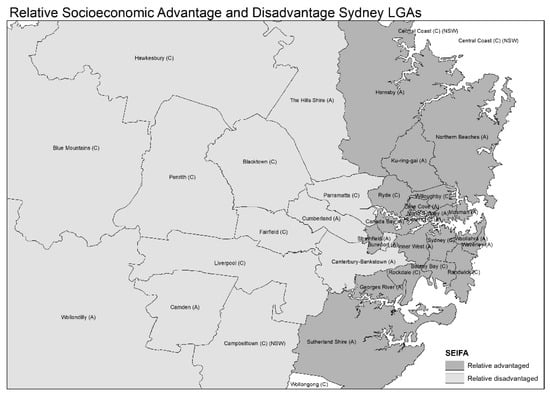

Freestone and Pinnegar (2021) argued that ‘Sydney has never been a shrinking city’ and Sydney’s urbanisation has experienced substantial changes over the decades. In this urban transformation process, some regions of Sydney have developed into centres of global businesses, professional services, knowledge, and many other innovative enterprise zones (Vogel et al. 2020). Conversely, some areas have transformed into disadvantaged regions considering urban opportunities due to unequal urban policy applications and uneven outcomes (Farid Uddin et al. 2022). The Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) SEIFA (Socio-Economic Indexes for Areas) Indexes of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage (IRSAD) at Statistical Area Level 2 shows that Sydney’s disadvantaged populations are clustered in the Greater Western Sydney (referred as Western Sydney) region, and advantaged residents are located in Sydney’s eastern and northern parts (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

The socio-economic advantage regions in Sydney. Source: authors’ own. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) Census 2016—SEIFA The Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage- IRSAD at Statistical Area Level 2. Local government boundaries are superimposed.

Although NSW’s urban planning policies, the planning system, and Sydney’s place-based inaccessibilities have been explored in previous research (MacDonald 2018; Roggema 2019; Ruming and Gurran 2014; Ruming 2019; Wiesel et al. 2018); however, contemporary critical studies on urban inequalities from urban planning perspective are absent. If urban scholarship intends to contribute to the city’s governance, democratisation, and equality, urban studies must critically identify and catalogue the city’s inequalities, rights, and power dynamics. In addition, examining urban disparities in a city that follow the same urban planning arrangement is essential to reduce urban exclusion. This research explores Sydney’s urban divide and conceptualises them in a critical theoretical context and empirical study.

This research contends that Sydney’s urban policy applications and outcomes are geographically differentiated based on socio-economic conditions. In addition, this research hypothesises that the planning system generates place-based inequities and reinforces the city’s pre-existent divisions by locating most new dwellings or populations in Western Sydney. The key research questions are: How has Sydney transformed into an increasingly unequal city? What is the position of the rights to the city in the disadvantaged geographies of Sydney?

2. Method

This research applies a qualitative method to analyse Sydney’s urban inequality in the urban planning context. In so doing, the paper utilises content analysis and semi-structured interviews to collect data. This research analyses hundreds of newspaper reports, web pages, metropolitan strategies, and literature to track Sydney’s contemporary urban planning trends and perceives society’s perceptions. The study also analyses secondary sources of publicly available data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics and the Department of Planning. Finally, the researchers also conducted 23 qualitative face-to-face and zoom interviews with four groups of interviewees, with conversations lasting between 30 and 70 min throughout 2019 and 2021 to gather individuals’ valuable opinions. Interviewees include local government officials, state and local politicians, experts and other stakeholders, and residents and community groups. However, this paper uses quotes from seven interviewees (Table 1), considering the relevance of the contents and the paper’s length.

Table 1.

Summary of interviewees associated with this paper.

3. Literature Review

Cities are the centre for entrepreneurialism, concentrating on growth and development; conversely, cities also generate adverse consequences for urban residents (Miraftab et al. 2015). Cities have increased the spectre of gentrification, intense poverty, homelessness, social isolation, violence, crime, affordability, ecological challenges, unequal access to opportunities, and many other difficulties (Storper and Scott 2016). Consequently, cities are being separated into the rich and the poor (Marcuse 1989). The prevailing urban inequality in cities is a critical academic interest. Besides, inequality in a global city such as Sydney draws much more earnest attention to understanding the form of urban discrepancies. The founding philosophy of urban planning practice is to make the city an equitable place for everyone (Yiftachel and Hedgcock 1993). Different schools of critical thought and philosophers delivered numerous planning theories concerning urban practices (Kincheloe and McLaren 2011). Critical theory can be defined as an essential critique of analytical tools to illuminate and inform the urban theory and practice that delivers fundamental concepts to improve socio-political discrepancy (Marcuse 2009). Critical urban studies employing critical theories are significant in exploring inequality from urban perspectives (Marcuse et al. 2014).

Various research has explored urban inequalities through different philosophical contexts. For example, Iveson (2013)’s analysis of urban practices concentrated on the right to the city theory. Marcuse (2009) applied the right to the city theory in the critical urban theory and practice. Using the power theory, Richardson (1996) analysed the policy process and planning, while Obeng-Odoom (2015) studied African urban inequality with the theory of neoliberalism.

Although critical theories are widely used in analysing numerous issues, some critics of critical theories exist. For example, Kellner (1990) argued that critical theories have been ineffective in developing and articulating changes, and postmodern and postindustrial theories have been deficient in continuous social research. In addition, critical theory is insufficient in analytically and precisely exploring its theories, methods, and norms; additionally, theorists failed to provide a unique narrative formula and a particular approach that provides the necessary and sufficient solutions to such limitations (Bohman 2005). However, there is optimism, as Kincheloe and McLaren (2011) claimed, that critical theory as a philosophy is often induced and misconstrued.

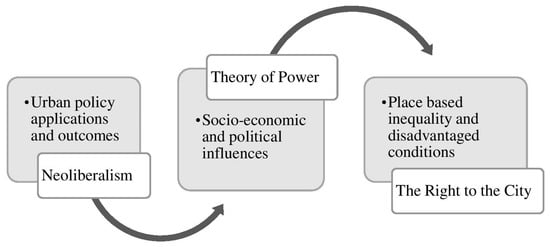

Though there are some criticisms of critical theories, the shifting trends of urban planning theory and practices that highly concentrate on economic efficiency and commodifications and hardly emphasise oppression, domination, and inequality in cities need a critical position in exploring urban planning roles (Yiftachel 1998). Therefore, critical theories remain vital for analysing the fundamental nature of urban disparities more than the traditional analytical focuses of urban planning theory and practices. This research considers that instead of a single theory, multiple theories can be framed together to explore urban planning issues (McFarland 2011). In addition, each theoretical concept can help balance the gaps between other theories. Considering the strengths, limitations, and prospects of critical theories, this research applied multiple critical theories to give thoughtful insight into the global city Sydney’s urban inequality. This research applied the combined critical urban theories (Figure 3) of neoliberalism, the theory of power, and the theory of the right to the city.

Figure 3.

Critical urban thoughts applied in this research. Source: authors’ own.

The urban political economy significantly manipulates the organisational actions influencing urban actions (Healey 2003). The political-economic power influence known as neoliberalism seems to be in all spaces (Peck and Tickell 2002). Neoliberalism is defined as political-economic dominance to expand the market and means to establish associations with the state to ensure the benefits of the market (Fainstein 2017). In addition, neoliberalism is a functioning structure for reforming various state agendas in national and local settings to enhance the supremacy of capital by ceasing the obstacles of the market (Fainstein 2017; Peck and Tickell 2002). Harvey (2008) argued that neoliberalism has produced new arrangements of power that integrate ‘state and corporate interests’.

The theory of power is as ancient as the history of philosophy (Moghadam and Rafieian 2019). Power is a complicated multifactorial idea that signifies the socio-economical capacity and authority to establish domination (Bathelt and Taylor 2002). It is significant to classify the features of urban planning and development from the standpoint of power and substantially important to discover planning and its applications aspects (Moghadam and Rafieian 2019). Moreover, Horsell (2006) argued that the perception of power is noteworthy in reframing the urban transformation.

The right to the city is a robust theoretical framework, practical slogan, and a right to access manifests urban amenities for underprivileged groups (Friendly 2013; Marcuse 2009; Qian and He 2012). The right to the city theory confirms its residents’ needs and supports a dignified and evocative daily life (Friendly 2013). Iveson (2013) argued that the right to the city’s thoughts is promising for progressive urban policy.

Commonly, disadvantaged situations and inequality are the differences in socio-economic conditions and lack of access to opportunities. The growing market-tailored policy changes involved in urban renovation and growth have shifted the fundamentals of urban life by pushing disadvantaged groups further behind (Bengtsson 2016). In the hegemonic neoliberal world order, the capacity to participate, contest, and modify the prevailing social order, the authority of commercialisation, and profit-boosting undermine the notions of rights (Brenner et al. 2012). Citizens’ rights in the city are continually narrowed down, confined, and controlled by the powerful political and economic elites who prioritise their interests rather than collective interest in modelling cities (Harvey 2008). Unequal urban settings generate, uphold, and imitate uneven power, thus impacting social orders and structures (Qian and He 2012). The market-oriented urban planning orthodoxy has created differences among various places in cities, whilst the disproportionate dispersal of urban services favours the needs of some groups above those of others in Sydney (Bengtsson 2016; Qian and He 2012).

Table 2 outlines the key focus of the applied critical theories and the relevant indicators to demonstrate their appropriateness in exploring and explaining contemporary urban inequalities in Sydney.

Table 2.

Key focus and indicators of critical analyses.

4. Findings and Analysis

Sydney has experienced a great deal of (ongoing) change in its socio-demographic geographies (Freestone and Pinnegar 2021). The NSW planning system and its strategies have been continuously restructured and re-instigated to consolidate, accelerate, and hand over planning powers to managerial bodies to ensure smooth development approval and a high pace of urban growth (Farid Uddin et al. 2022; MacDonald 2018; Ruming and Gurran 2014). This study contends that NSW urban planning considers the planning organisation and their associate’s interests in their urban transformation process instead of focusing on underprivileged regions’ added opportunities aligned with advantaged regions. Thus, Sydney’s urban growth leads to a cities-within-a-city divide. The following subsections outline Sydney’s existing urban divide from critical urban theoretical perspectives.

4.1. Neoliberal Urbanity

The neoliberal process transforms the state’s intentions by concentrating on economic and market-centric approaches (Springer 2012). Urban planning in Sydney has a long history of neoliberal influence, and the critical concentration of policy reforms has been enacted to ensure the market’s interests (MacDonald 2018). The NSW government introduced the Environmental Planning and Assessment (EP&A) Act in 1979 to ensure public participation in the planning process; however, numerous amendments have been made to the EP&A 1979 since then. Urban policy reform inventions, such as complying development, state-significant infrastructure development, the low-rise housing diversity code, and the provision of private certifiers, have facilitated new developments via an easier and faster process. The easy-going approval process and options for more new urban development benefit the political economy of urban growth and development (Healey 2003). One interviewee of this study noted:

“… it (policy reform) is persuaded by politics and politicians, particularly from the right side. They are obviously for development and pro-development, and they want to make development a lot easier to occur. They feel that doing it through a SEPP (State Environment Planning Policy) and then obviously having the opportunity for complying development, because it happens quicker, there will be more opportunities for development. They will not be held back from doing those sorts of developments. So, it (complying development) is a pro-development opportunity.”(Interviewee O4)

Over the last two decades, the population growth estimated in Sydney’s strategic plans has progressively risen, and each plan unveiled a higher target than the previous (Troy et al. 2020). In addition, new housing development employing higher-density infill development in the outer regions is a central aim of the metropolitan strategy (Gilbert and Gurran 2021; Troy et al. 2020). As a result, there has been a growing push by the state authorities to increase density and make more land available for new housing in the west of Sydney.

Western Sydney is the largest region in Sydney. Currently, it comprises 44% of Sydney’s population and has become one of Australia’s largest-growing urban regions, which is predicted to accommodate around two-thirds of Sydney’s metropolitan population by 2036 (Farid Uddin and Piracha 2022). The most recent metropolitan strategy, the 2018 Region Plan, and the associated District Plans have set a new housing supply target of 725,000 in the Sydney Metropolitan area for the next 20 years (GSC 2018b).

Although the indicative goal of creating good jobs and enhanced opportunities closer to peoples’ residences is at the forefront of the strategies, the key objectives of the state planning departments are to promote housing and population growth in NSW. Subsequently, the urban strategic plan ensures urban growth by setting housing and population targets for the local government areas. One interviewee noted:

“For 25 years in Sydney, the state government used to produce urban development programs, and this basically set out where all new development was scheduled to be happening across the Greater Sydney area and was updated on an annual basis with interaction with all the key developers and state government agencies to have a robust and one source of truth about where new housing was going to be provided over a five-year period.”(Interviewee S3)

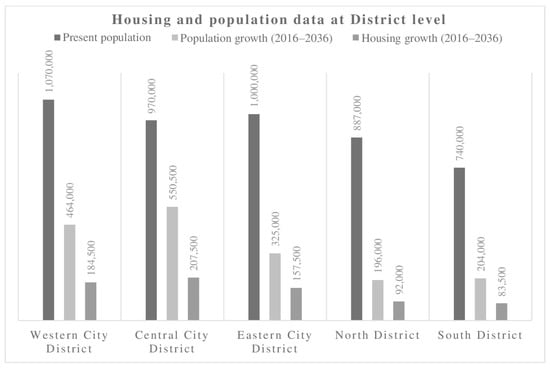

One of the urban planning objectives is to balance the distribution of jobs as ‘journey to work’ problems have been created as a consequence of the high level of employment and other commercial activities concentrated in Sydney city’s central area and surrounding regions, distant from residents in the west. NSW urban planning has positioned Western Sydney as the urban area to accommodate Sydney’s population growth. Of the housing supply target of 725,000 in the ‘A Metropolis of Three Cities’ (GSC 2018b) strategy, Western Sydney received a higher target than other districts (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Current population and forecasted housing and population targets by District 2016 and 2036. Source: authors’ own. Data from the Greater Sydney Commission District Plans, accessed from https://www.greater.sydney/strategic-planning, on 14 February 2021.

Figure 4 shows that the two districts of Western City and Central City (both parts of Greater Western Sydney) have been allocated 54% of the total new housing target. In contrast, the East District received 22% and the North District received 13%. In reality, the geographic positions of the Central City and Western City were understood as Western Sydney prior to the inception of the Greater Sydney Commission in 2015. The Western City District LGAs include Blue Mountains, Camden, Campbelltown, Fairfield, Hawkesbury, Liverpool, Penrith, and Wollondilly, and the Central City District LGAs include Blacktown, Cumberland, Parramatta, and The Hills. Central City is a new designation for a part of Western Sydney, as those LGAs are a fragment of the Greater Western Sydney region. It can be argued that the new designation, such as Western City, Central City, and Western Parkland City, is the neoliberal concept of cities within a city to achieve the state government’s urban strategic intent. Whatever the city’s name or designation, all areas fall over to the Greater Western Sydney region.

The NSW Government’s existing plans add considerably to Sydney’s housing provision. The government’s urban planning and development authorities significantly focus on the western part of Sydney as a suitable location for additional housing and populations. The Department of Planning and Environment (DoP&E), the Greater Sydney Commission, and the infrastructure deal (Western Sydney City Deal) also target Western Sydney as a suitable place for urban growth. In this process of neoliberal urban growth, more and more people and housing are being addressed in Western Sydney’s suburbs. At the same time, advantaged areas have much lower housing targets than Western Sydney (Gellie 2019).

The NSW planning department’s (DoP&E 2021) housing supply forecast over the five years from 2020–2021 to 2024–2025 for Sydney LGAs shows that the targets for new housing in Western Sydney are significantly higher than the other areas. Around 61% of the new housing supply is allocated to Western Sydney LGAs. Even a local government area of Western Sydney is positioned for a 178% population increase by 2036 (GSC 2018a). Conversely, Sydney’s eastern and northern LGAs have only very small targets. It is also worth noting that Sydney’s eastern and northern regions are unlikely to meet their new housing provision targets because of strong local opposition (Farid Uddin et al. 2022). Farid Uddin et al. (2022) further argued that the eastern and northern residents and community groups actively participate in urban planning consultation, they strongly oppose neoliberal urban growth, and even the neoliberal urban policies are applied differently in various regions of Sydney considering residents’ socio-economic conditions. Western Sydney has always been a place for more housing sites and a target of neoliberal economic gains that serve urban capitalism’s interest (Miraftab et al. 2015). One interviewee noted:

“Urban development gets further and further from the city, more impacted largely by traffic congestion and air quality problems… it is not a strategic planning shift; it is just a response to the market.”(Interviewee P3)

In Australia, the housing market is an important economic sector for the government, private sector, and individuals, as earnings from housing have become a leading revenue provider (Ryan-Collins and Murray 2021). Property development lobby groups dominate the planning systems across Australia, and in Sydney, the government’s urban planning reforms are pursued mainly by developers and supported by neoliberal economic objectives (Gilbert and Gurran 2021; Troy et al. 2020).

In the market-led and economic-centric planning practices (Troy et al. 2020), the NSW state government’s key urban planning motivation is to place excessive housing development to attain the neoliberal economic benefits. The state provides direct aid (First Home Buyers Grants) and indirect financial support (negative gearing via the taxation system) to boost the housing market (Ryan-Collins and Murray 2021). Since 2000, Australia has been considered first or second in house price increase (Ryan-Collins and Murray 2021), and the government continually promotes new housing supply to boost economic growth (Troy et al. 2020). The new housing development leads to the expansion of the market economy and directs unsought consequences in parts of Sydney.

Substantial homeowners or landlords in Western Sydney are investors, as significant capital gains from housing properties influence them to buy properties as a secured investment (Pawson and Martin 2020). Bangura and Lee (2022) also claimed that Western Sydney is a comparatively low-income area with an elevated amount of investor focus, making it a housing bubble-prone region. Troy et al. (2020) argued that Sydney’s strategic and regulatory urban planning contexts have cleverly been bestowed with the notion of ‘growth-dependent planning’. Thus, 2018′s strategic regional and related subregional plans also emphasise urban growth by placing excessive housing targets. The NSW planning department’s neoliberal development approach has placed more housing in Western Sydney, widening Greater Sydney’s place-based inequalities.

4.2. Exercise of Power

Power is instituted in societies that successively dominate the social order (Innes and Booher 2015). Power is often also masked within government structures (Stein and Harper 2003). Njoh (2009) argued that citizens are progressively under the state’s control and that the state wants to supervise citizens’ activities highly. Multiple planning organisations, such as the Department of Planning and Environment, the Independent Planning Commission, Local Planning Panels, and the Greater Cities Commission (former Greater Sydney Commission), are part of the planning device. In addition, numerous urban planning policies and plans, such as the Environmental Planning and Assessment Act 1979 (EP&A Act), the State Environmental Planning Policy (SEPP), the Local Strategic Planning Statement, the Development Control Plan, the Local Environmental Plan, and the Community Participation Plans, as well as various regional and subregional strategic plans exist in the NSW planning structure. Cumulatively, it is not viable for all communities to learn these bulk of planning policies, consequently making the planning system complex for residents (Farid Uddin et al. 2022; Ruming 2019). The lower socio-economics residents have poor educational backgrounds and social circumstances, which makes it difficult for them to go through the planning regulations. One interviewee noted that:

“If you do not come from a planning background, you need to do a lot of research. There are so many things that you can potentially be following; you have to prioritise which ones. You have to teach yourself in a way and connect with people who can give you good advice and professional expertise.”(Interviewee R5)

However, within the existing scope of community engagement, the advantaged areas always find ways to actively contribute to the planning procedure to control urban planning consequences (Ruming 2019). It follows that differential community engagement abilities significantly influence policy applications. One interviewee noted that:

“Some parts of Sydney are very active, and again they are active on the local level because they care about what is happening to them. So that sort of just skews how the plan is happening a little bit. In an affluent area, people usually have a lot more resources, so they have time, finances, access to computers all day, and access to people’s skill sets, so it is easy to organise groups around a particular issue. Which, when you are in the outer suburb again, people are less affluent, so they struggle to…”(Interviewee P2)

Community groups’ abilities, the scope of engagement potentials, and skills to enact the same differ across Sydney’s urban geographies according to the socio-economic characteristics and geographic positions of particular areas. Ruming (2019) claimed that high-income and inner suburb people are more conscious of planning contexts and are typically enthusiastic about playing a part in planning consultations; on the other hand, lower-income Western Sydney residents lack planning knowledge and do not engage in planning consultations. Gurran and Phibbs (2013) also argued that there have been higher disagreements with urban policy applications and practices in some regions of Sydney than in others. In detail, the west of Sydney possesses lower educational attainment levels and jobs of lower status compared to other parts of Sydney. Consequently, residents’ skills and competencies differ between several areas of Sydney’s urban geography, increasing gaps in urban planning applications, practices, and outcomes in some regions (Farid Uddin et al. 2022).

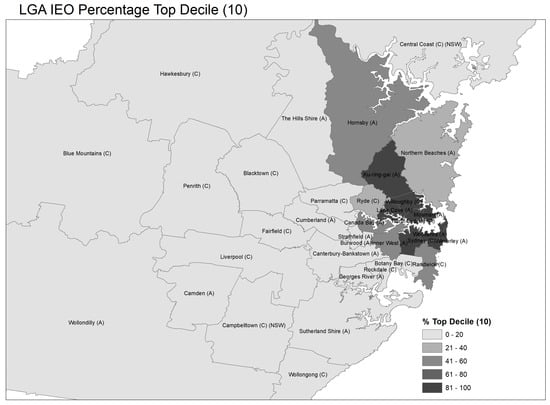

The ABS Index of Education and Occupation (IEO) outlines the residents’ occupational and educational positions. The occupation variables divide employees into significant clusters and skilfulness ranks of the Australian and New Zealand Standard Classification of Occupations (ANZSCO) and the jobless. A lower score specifies that the given individual has a comparatively lesser education and poor occupation position compared to other individuals in the region. In general, if there are a lot of people with fewer qualifications, with low-skilled jobs, or who are unemployed, and a minor amount of people with a high level of qualifications, this leads to a lower score. In opposition, if there are more educated people and people with a good occupation status in the area, with only some individuals with poor qualifications or skilled jobs, this leads to a higher score in IEO.

Figure 5 shows the IEO for Sydney LGAs with the proportion of decile ten areas; this informs people’s occupational and educational positions. The map demonstrates the ratio of people in individual LGAs. In total, 100% of individuals of Hunters Hill, Ku-ring-gai, Lane Cove, Mosman, North Sydney, Sydney City, Waverley, Willoughby, and Woollahra LGAs are in the top IEO decile. In contrast, 11 of the 13 LGAs in Western Sydney are positioned in the lowest quartile. This means that none of the Blacktown, Blue Mountains, Camden, Campbelltown, Canterbury-Bankstown, Cumberland, Fairfield, Hawkesbury, Liverpool, Penrith, and Wollondilly local government areas are in the top decile with regard to educational and occupational positions. This reflects that a higher amount of people in Western Sydney have a poor income and education and stay in underprivileged conditions due to their lack of access to opportunities. The dearth of socio-economic prospects drives people to remain in a weak position.

Figure 5.

Sydney LGAs IEO percentage (decile 10). Source: authors’ own. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016 Census.

The residents of affluent areas in Sydney’s north and east are very insistent, involved in urban planning matters, and strongly oppose urban growth and development (Farid Uddin et al. 2022; Ruming 2019). The elites increasingly apply resources and networks effectively to maximise their benefits; on the other hand, the excluded disadvantaged groups are left behind when it comes to bargaining with institutional powers (Farid Uddin et al. 2022). One interviewee noted that:

“Some people are going to have louder voices than others and be more convincing—they are going to be better resourced to make more convincing cases than others.”(Interviewee P3)

The weak socio-economic position also leads to a poor position in urban planning practices. Consequently, Western Sydney residents have weak involvement in urban planning consultation. A higher number of housing and population targets of urban authorities should be in areas with good access to education and income opportunities. However, Sydney’s urban planning context is the opposite, and immense urban growth is placed in the less advantaged and geographically far away urban areas of Western Sydney. DoP&E (2021) statistics show that most of the dwellings built in the past five years in Sydney have been constructed within the territories enveloped by Western Sydney LGAs. It is also the case that new housing growth forecasts for the forthcoming five fiscal years are much higher for these areas. On the other hand, the privileged east and north areas have lower housing targets than Western Sydney (Gellie 2019).

The arguments and evidence indicate that power domination is predominant in Sydney’s urban planning practices. The affluent and advantaged northern and eastern Sydney residents have a strong position in Sydney’s urban planning in bargaining and opposing undesired urban growth considering their powerful socio-economic and political status. The powerful stance of particular residents controls the initiation, implementation, and reform of urban policies, thereby leading to splits in Sydney’s urban locations.

4.3. Rights to the City

Lefebvre (1976) claimed that the right to the city is a point of view where specific communities will not be placed in a location that generates place-based inaccessibility. It follows that residents must have the right to entry to the city’s opportunities and benefits (Friendly 2013). The western part of Sydney lacks qualifications, skills, and jobs (Figure 5). The residents of Western Sydney struggle to access better jobs, good education, and modern urban facilities. In addition, the NSW urban planning strategy has been positioning nearly all new populations in Western Sydney, where the existing residents struggle to survive with the disadvantaged in lifestyles and opportunities. The population of affluent areas have decreased where there are more opportunities; conversely, Western Sydney areas are carrying the growth of Sydney metropolitan and Western Sydney ‘people at the coal face of the city’s growth’ with poor infrastructure facilities (Koziol 2022). This unequal position creates a depressing situation where residents fight for their fundamental rights to maintain their livelihoods. One interviewee suggested that:

“The bigger point here is no point in increasing the population density if you do not create more jobs or facilities. If people have to travel to Sydney or North Sydney or somewhere in Parramatta, then what is the point of having too many people here in Western and South Western Sydney? The government should support creating jobs locally, so people do not have to travel.”(Interviewee R3)

The quiet Western Sydney suburbs are becoming congested and chaotic with the growing population. The people moving to the new suburbs are experiencing inadequate socio-economic services. For example, Marsden Park, one of Sydney’s growing suburbs, is located in Greater Western Sydney, where thousands of new houses are already built, and additional thousands are planned where even minimum urban infrastructure is not available (Baker 2022). One frustrated home buyer of Marsden Park remarked in the media (Baker 2022) that:

“The public primary was the size of a country school and now has 19 demountables. The closest shops were 20 min away; if she forgot milk, it was a 40-min round trip, often in traffic. Trains came hourly, even at the peak. Narrow roads were choked. The hospital repeatedly promised for nearby Rouse Hill didn’t exist, and still does not. Meanwhile, the population grows exponentially.”(A disappointed resident of Western Sydney’s brand-new suburb)

In addition to the excessive growth and lack of facilities, the disadvantaged regions are experiencing lower support compared to the affluent. For example, the NSW government introduced ‘The Stronger Communities Fund’ in 2016 to assist councils (Local Government) affected by forced council mergers. The reform largely impacted the Western Sydney LGAs, who could get maximum funding. However, the rules were changed in June 2018 to allocate funds to councils, irrespective of whether they had merged. The funds were allocated purposefully to gain political benefits in certain councils. For example, the affluent northern Sydney Hornsby Shire council controversially obtained 90 million AUD to renovate a quarry into a park, which was strange and at least 30–40 times higher than the councils who received the fund (Cormack and O’Sullivan 2022). Greater Western Sydney is the third-largest economy in Australia, with a higher population, and Western Sydney residents significantly contribute to the state and country’s socio-economic progress (Soldatic et al. 2020). However, Greater Western Sydney lags behind other areas with regard to access to infrastructure and amenities (Farid Uddin and Piracha 2022; Soldatic et al. 2020; Wiesel et al. 2018). The right to the city’s appeal of Western Sydney is not for luxury; instead, it is to achieve fundamental rights that should be available for every citizen in the city, such as quality jobs, good education, good infrastructure, and better natural environments.

The concept of a city’s right is a dynamic, practical slogan for disadvantaged classes. Mayer (2009) claimed the right to the city as a living slogan that transforms cities. Thus, the right to the city offers the opportunity for disadvantaged residents to expose and demand their urban rights, which allows them the courage to question the government and urban authorities. One interviewee questioned:

“Why is Parliament House in Macquarie Street? Why isn’t it at Blacktown or Penrith or Campbelltown or Liverpool? Why isn’t it at the new Aerotropolis? …… Why is that?”(Interviewee O3)

Government policies and strategies foster progress and empowerment in society. However, there is a difference between regions in Sydney considering the right to the city and empowerment. In addition to the specific urban rights, such as job, income, housing affordability, or amenities, the disadvantaged Western Sydney residents appeal for the right to the city catchphrase for equality, empowerment, and capacity-building that will lead to equal opportunity in Sydney’s unequal urban geographies.

5. Discussion

Sydney’s urban planning system, practices, and outcomes indicate that the state advances the market’s interests by accommodating Sydney’s extended population and dwellings in Western Sydney. In addition, the residents of the advantaged area are aware of planning issues. They have established social and political control in urban planning and can easily accomplish their planning objectives. Conversely, residents of less affluent and disadvantaged regions are unable to influence urban planning. They essentially fail to set their intent and stay behind in securing their interest in the established state planning system’s obstacles or by the manoeuvres of the powerful socio-economic groups. Thus, NSW urban policy practices induce a surge of inequality in Sydney with undesirable urban consequences in the disadvantaged west.

The government predicts that the construction of Western Sydney International Airport will generate thousands of jobs and facilities for residents of Western Sydney. However, it is argued in the media that the job projection is “exaggerated and inflated at least four-fold” (Madigan 2018). In addition, the most disadvantaged areas in Western Sydney have experienced significantly lower levels of infrastructure investment (Wiesel et al. 2018). In addition, many highly underprivileged Western Sydney people live in unfortunate natural and physical environments. New houses are built on small plots that leave minimal spaces between houses and only provide small open spaces and gardens (Roggema 2019).

Western Sydney is also hotter in summer, has less annual rainfall, and is more prone to bushfires and floods than Sydney’s north and east parts. For example, in January 2020, portions of the Western Sydney region experienced up to 52.0 degrees Celsius (Pfautsch et al. 2020). In contrast, the coastal inner eastern and northern neighbourhoods were much cooler. Many houses in the west must have air conditioners to cope with high temperatures, increasing residents’ electricity costs. Residents in Western Sydney also face longer commute times and higher travel costs to reach amenities and jobs compared to those in other parts of Sydney. Once more, this strains household budgets and reduces disposable incomes (Roggema 2019).

Urban planning is far behind in ensuring residents’ benefit (Gibson et al. 2022); as a result, the urban disparity in Greater Sydney is expanding (Farid Uddin et al. 2022). In Greater Sydney’s urban settings, the notion is that urban planning reinforces divisions within the city by favouring affluent neighbourhoods in urban policy applications, particularly regarding placing added houses or people. Housing and population growth impose hefty burdens on urban opportunities, as existing opportunities cannot cope with further increased density (Olajide et al. 2018). Western Sydney currently houses nearly half of Sydney’s inhabitants and is expected to contain nearly two-thirds of the total population by 2036 (GSC 2018b).

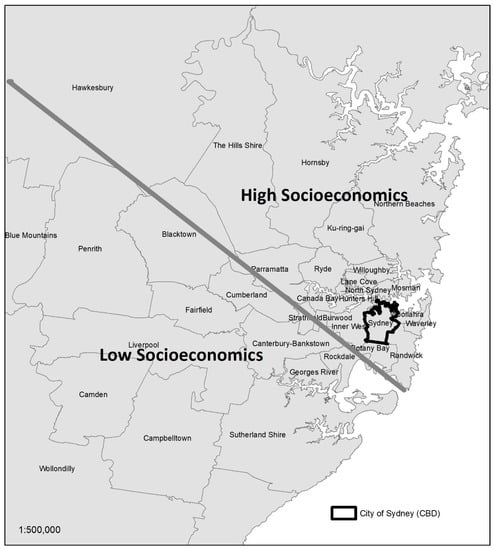

This study defines the division as an ‘east–west divide’ (Figure 6), as Sydney’s north and south parts are essentially northeast and southeast of Sydney, which is also partway to the east of Sydney. A dividing line splits the affluent and well-positioned east from the less affluent and underprivileged west. This diagonal line extends from northwest to southeast and distinguishes Greater Sydney’s division.

Figure 6.

The east–west urban divide in Greater Sydney. Source: authors’ own. Data from the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) 2016 digital local government boundaries.

The disadvantaged areas in Western Sydney face various difficulties, and the advantaged areas in eastern and northern Sydney are places of wealth and opportunity. Instead of minimising the gap, the NSW urban planning is placing Sydney’s western areas in harsh situations with a lack of access to sufficient amenities and opportunities by placing a vast population and housing. The high socio-economic eastern and northern areas are attracting high-tech investment and skilled employment and have become the global economic corridor of Greater Sydney (Vogel et al. 2020). Conversely, the low socio-economic Western Sydney suburbs have significantly lower levels of investment in innovation precincts, business parks, and educational facilities and higher levels of urban growth. While capital is directed to western suburbs, it is often towards new housing development and state-needed infrastructure (airport), reinforcing both the concentration of poverty and lack of access to urban amenities (Wiesel et al. 2018). The affluent are favoured in neoliberal urban growth and experience fewer housing and population targets, whilst benefitting from expanded opportunities. In contrast, the disadvantaged regions have extreme urbanisation instead of greatly needed urban opportunities and infrastructure support. The NSW urban planning practices are strongly influenced by socio-economic power; consequently, high socio-economics areas influence urban growth and development. In contrast, the less affluent residents of low socio-economic areas of Sydney are deprived of their urban rights and their livelihoods are challenged by the cities-within-a-city divide.

6. Conclusions

The existing geographical divide in its urban settings is a significant challenge to Sydney’s global reputation and is miserable for its residents, specifically disadvantaged Western Sydney people. Steil and Connolly (2019) argue that as urban inequality lingers and exclusions increase, attention to righteousness in the principle of urban policies is essential. Cities must reconsider and prioritise eliminating inequalities in urban geographies. Pursuing an equal city entails a fundamental transformation of urban planning and policy practices that ensure more openness, intense consensus, and inclusiveness in urban settings (Steil and Connolly 2019). The NSW state government’s urban planning organisations have advanced various policy reforms and initiated strategies to ensure an innovative and connected Greater Sydney. However, urban inequality and place-based underprivileged conditions continue to challenge Sydney’s growing urban expansion and development. This research has outlined Sydney’s urban inequalities from an urban planning perspective. Neoliberal planning is fully applied in Western Sydney, whereas the eastern and northern parts of Sydney receive exemptions because of their politics, clout, and ability to resist. The neoliberal planning purposes and institutional and socio-economic influence contribute to unequal urban outcomes that deepen the urban division in Sydney.

Consequently, it ignores the urban rights of nearly half of Sydney’s residents who live in disadvantaged Western Sydney regions. NSW urban planning systems fundamentally require uniform applications of urban policy and just urban geography with equal access to urban opportunities for all regions. Numerous scholars have acknowledged that urban inequality exists and shared viewpoints for equal cities and empowered communities. For example, Fainstein (2010) debates urban political philosophy, spatial phenomena, and social justice and introduces the “Just City” concept to develop an urban philosophical and practical notion to ensure urban justice in city planning and the development policy realm. A just city concept requires three urban governing principles, equity, diversity, and democracy, as the essential tools for urban equality (Fainstein 2010, 2014). It emphasises the need for a shift in the reasoning, strategic action and execution of urban policies to improve the quality of urban residents’ lives. Equity emphasises the equal distribution of socio-economic and political opportunities; diversity stress confirming that people are not excluded for their social, political and economic conditions; and finally, democracy involves establishing democratic processes in urban plans and policies focusing on the participation of minor, disadvantaged people and enhanced consultation in the underprivileged areas (Fainstein 2010; Steil and Connolly 2019). Fainstein (2014) argues that ‘the stronger the role of disadvantaged groups in policy decisions, the more redistributional will be the outcomes; thus, broad participation and deliberation should produce more just outcomes’.

This paper emphasises the significance of a just city and strong community engagement in NSW urban planning to reduce Sydney’s cities-within-a-city divide. The state government must also ensure necessary support by adding infrastructure and improving existing facilities, resources, and opportunities by considering the needs of the disadvantaged regions. It highlights the need for an equal distribution of socio-economic, political, and cultural infrastructure, resources, and opportunities to ensure a just Sydney. This research also urges empowering local politics, increasing information sharing, enhancing partnerships, and improving community participation efforts to ensure that disadvantaged residents may be actively engaged in the planning process.

This research is necessarily critical in the sense of negative criticism of the urban planning system and its practices; however, it has not only decried urban planning practices, but also critically exposed the aspects that lead a city to a divided city. The findings of this research are crucial for urban practitioners and policymakers to rethink urban policy practices. This research has sought to add to existing urban studies knowledge by critically exploring urban inequalities from an urban planning perspective. The key contribution of the research is that it highlights that Sydney’s urban planning policy and practices are deepening the intra-city socio-economic divide. The research has contributed to the existing urban literature by integrating planning policy and practice and urban inequality in the framework of neo-critical discourse. This research develops a combined critical approach by relating critical theories of neoliberalism, theory of power, and the right to the city. Besides, this research is the evidence for policymakers, practitioners, urban managers, and researchers to rethink existing urban practices. Finally, this research provides a framework to study and analyse socio-economic divisions in other global cities. However, this research is confined to certain aspects of urban facets and limited to qualitative methods with a relatively small number of informants. Future research can explore urban inequality more broadly, address the challenges of urban inequalities, and identify techniques to ensure just and better cities by employing wider qualitative and quantitative approaches.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.F.U. and A.P.; methodology, K.F.U.; formal analysis, K.F.U.; investigation, K.F.U.; writing—original draft preparation, K.F.U.; writing—review and editing, A.P.; visualisation, A.P.; supervision, A.P.; project administration, K.F.U. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was not supported by a grant.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was reviewed and approved by the Western Sydney University Human Research Ethics Committee; the approval number is H13384.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all informants involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

All data are stored in the Western Sydney University Research Data Repository “ResearchDirect”.

Acknowledgments

The authors are thankful to the interviewees for volunteering their time and delivering invaluable thoughts. Special thanks to the journal’s editorial team for the insightful comments on the earlier version of the paper and for providing helpful support. Furthermore, the anonymous reviewers are thanked for delivering valuable and constructive comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, Jordan. 2022. ‘Here’s what’s missing—Everything’: No schools and noservices but houses keep going up. The Sydney Morning Herald, October 15. [Google Scholar]

- Bangura, Mustapha, and Chyi Lin Lee. 2022. Housing price bubbles in Greater Sydney: Evidence from a submarket analysis. Housing Studies 37: 143–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathelt, Harald, and Mike Taylor. 2002. Clusters, power and place: Inequality and local growth in time–space. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 84: 93–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, Stina. 2016. The Right to the Citi (zen) Urban Spaces in Commercial Media Environments. Space and Culture 19: 478–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohman, James. 2005. Critical theory. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Edited by Metaphysics Research Lab. Stanford: Stanford University. [Google Scholar]

- Brenner, Neil, Peter Marcuse, and Margit Mayer. 2012. Cities for People, not for Profit: Critical Urban Theory and the Right to the City. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Clegg, Stewart R. 1989. Frameworks of Power. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Cormack, Lucy, and Matt O’Sullivan. 2022. Berejiklian oversaw program to issue councilgrants ‘in the most politically advantageousway’. The Sydney Morning Herald, February 8. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Kathryn, and Michael Arman. 2014. Planning for sustainability: An assessment of recent metropolitan planning strategies and urban policy in Australia. Australian Planner 51: 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, Mitchell. 2013. The Signature of Power: Sovereignty, Governmentality and Biopolitics. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- DoP&E. 2021. Sydney Housing Supply Forecast Insights. Available online: https://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Research-and-Demography/Sydney-Housing-Supply-Forecast/Forecast-data (accessed on 12 September 2022).

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2010. The Just City. Ithaca and New York: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2014. The just city. International Journal of Urban Sciences 18: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fainstein, Susan S. 2017. Urban planning and social justice. In The Routledge Handbook of Planning Theory. London: Routledge, pp. 130–42. [Google Scholar]

- Farid Uddin, Khandakar, and Awais Piracha. 2022. Sustainable and Resilient Community in the Times of Crisis: The Greater Sydney Case. In Community Empowerment, Sustainable Cities, and Transformative Economies. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 475–93. [Google Scholar]

- Farid Uddin, Khandakar, Awais Piracha, and Peter Phibbs. 2022. A tale of two cities: Contemporary urban planning policy and practice in Greater Sydney, NSW, Australia. Cities 123: 103583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, Clive. 2006. The challenge of change: Australian cities and urban planning in the new millennium. Geographical Research 44: 173–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, Niki, Cathy Oke, Guy Barnett, Sarah Bekessy, Judy Bush, James Fitzsimons, Maria Ignatieva, Dave Kendal, Jonathan Kingsley, and Laura Mumaw. 2022. A transformative mission for prioritising nature in Australian cities. Ambio 51: 1433–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freestone, Robert, and Simon Pinnegar. 2021. Sydney: Evolution Towards a Tri-city Metropolitan Region and Beyond. In The Routledge Handbook of Regional Design. London: Routledge, pp. 263–83. [Google Scholar]

- Freestone, Robert, and Stephen Hamnett. 2017. Australian Cities and Their Metropolitan Plans Still Seem to Be Parallel Universes. Available online: http://theconversation.com/australian-cities-and-their-metropolitan-plans-still-seem-to-be-parallel-universes-87603 (accessed on 28 June 2018).

- Friendly, Abigail. 2013. The right to the city: Theory and practice in Brazil. Planning Theory & Practice 14: 158–79. [Google Scholar]

- Gellie, Campbell. 2019. Two Tales. The Daily Telegraph, February 11. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, Chris, Crystal Legacy, and Dallas Rogers. 2022. Deal-making, elite networks and public–private hybridisation: More-than-neoliberal urban governance. Urban Studies 60: 183–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, Catherine, and Nicole Gurran. 2021. Can ceding planning controls for major projects support metropolitan housing supply and diversity? The case of Sydney, Australia. Land Use Policy 102: 105278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GSC. 2018a. OUR GREATER SYDNEY 2056, Western City District Plan– Connecting Communities. Edited by Greater Sydney Commission. Sydney: Greater Sydney Commission. [Google Scholar]

- GSC. 2018b. Greater Sydney Region Plan A Metropolis of Three Cities. Sydney: Greater Sydney Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Gurran, Nicole, and Peter Phibbs. 2013. Housing supply and urban planning reform: The recent Australian experience, 2003–2012. International Journal of Housing Policy 13: 381–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2008. The right to the city. New Left Review 53: 23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Patsy. 2003. Collaborative planning in perspective. Planning Theory 2: 101–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsell, Chris. 2006. Homelessness and social exclusion: A Foucauldian perspective for social workers. Australian Social Work 59: 213–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyötyläinen, Mika. 2019. Divided by policy: Urban Inequality in Finland. Helsinki: University of Helsinki. [Google Scholar]

- Innes, Judith E., and David E. Booher. 2015. A turning point for planning theory? Overcoming dividing discourses. Planning Theory 14: 195–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iveson, Kurt. 2013. Cities within the city: Do-it-yourself urbanism and the right to the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 37: 941–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, Douglas. 1990. Critical theory and the crisis of social theory. Sociological Perspectives 33: 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, Joe L., and Peter McLaren. 2011. Rethinking critical theory and qualitative research. In Key Works in Critical Pedagogy. Bold Visions in Educational Research. vol. 32, Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, pp. 285–326. [Google Scholar]

- Koziol, Michael. 2022. Punishment or reward? The housing remark that revivedSydney’s east-west divide. The Sydney Morning Herald, November 12. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1976. The Survival of Capitalism. London: Allison and Busby. [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, Heather. 2018. Has planning been de-democratised in Sydney? Geographical Research 56: 230–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madigan, Damien. 2018. Jobs for the West report slams Western Sydney Airport jobs claims. Blue Mountains Cazette, August 20. [Google Scholar]

- Marcuse, Peter, David Imbroscio, Simon Parker, Jonathan S. Davies, and Warren Magnusson. 2014. Critical urban theory versus critical urban studies: A review debate. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38: 1904–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, Peter. 1989. ‘Dual city’: A muddy metaphor for a quartered city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 13: 697–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcuse, Peter. 2009. From critical urban theory to the right to the city. City 13: 185–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, Margit. 2009. The ‘Right to the City’in the context of shifting mottos of urban social movements. City 13: 362–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, Paul. 2011. The best planning system in Australia or a system in need of review? An analysis of the New South Wales planning system. Planning Perspectives 26: 403–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraftab, Faranak, David Wilson, and Ken Salo. 2015. Cities and Inequalities in a Global and Neoliberal World. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Moghadam, Seyed Navid Mashhadi, and Mojtaba Rafieian. 2019. If Foucault were an urban planner: An epistemology of power in planning theories. Cogent Arts & Humanities 6: 1592065. [Google Scholar]

- Njoh, Ambe J. 2009. Urban planning as a tool of power and social control in colonial Africa. Planning Perspectives 24: 301–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obeng-Odoom, Franklin. 2015. The social, spatial, and economic roots of urban inequality in Africa: Contextualizing Jane Jacobs and Henry George. American Journal of Economics and Sociology 74: 550–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olajide, Oluwafemi Ayodeji, Muyiwa Elijah Agunbiade, and Hakeem Babatunde Bishi. 2018. The realities of Lagos urban development vision on livelihoods of the urban poor. Journal of Urban Management 7: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pawson, Hal, and Chris Martin. 2020. Rental property investment in disadvantaged areas: The means and motivations of Western Sydney’s new landlords. Housing Studies 36: 621–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, Jamie, and Adam Tickell. 2002. Neoliberalizing space. Antipode 34: 380–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfautsch, Sebastian, Agnieszka Wujeska-Klause, and Susanna Rouillard. 2020. Benchmarking Summer Heat Across Penrith, New South Wales. Sydney: Western Sydney University. [Google Scholar]

- Pusey, Michael, and Shaun Wilson. 2003. The Experience of Middle Australia: The Dark Side of Economic Reform. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, Junxi, and Shenjing He. 2012. Rethinking social power and the right to the city amidst China’s emerging urbanism. Environment and Planning A 44: 2801–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Tim. 1996. Foucauldian discourse: Power and truth in urban and regional policy making. European Planning Studies 4: 279–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roggema, Rob. 2019. Australian Urbanism; State of the Art. In Contemporary Urban Design Thinking. The Australian Approach. Edited by Rob Roggema. Cham: Springer, pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ruming, Kristian, and Nicole Gurran. 2014. Australian planning system reform. Australian Planner 51: 102–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruming, Kristian. 2019. Public Knowledge of and Involvement with Metropolitan and Local Strategic Planning in Australia. Planning Practice & Research 34: 288–304. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan-Collins, Josh, and Cameron Murray. 2021. When homes earn more than jobs: The rentierization of the Australian housing market. Housing Studies, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soldatic, Karen, Liam Magee, Paul James, Shuman Partoredjo, and Jakki Mann. 2020. Disability and migration in urban Australia: The case of Liverpool. Australian Journal of Social Issues 55: 456–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Springer, Simon. 2012. Neoliberalism as discourse: Between Foucauldian political economy and Marxian poststructuralism. Critical Discourse Studies 9: 133–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steil, Justin, and James Connolly. 2019. Just City. The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Urban and Regional Studies, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stein, Stanley M., and Thomas L. Harper. 2003. Power, trust, and planning. Journal of Planning Education and Research 23: 125–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Storper, Michael, and Allen J. Scott. 2016. Current debates in urban theory: A critical assessment. Urban Studies 53: 1114–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, Andrew. 2021. ‘Postcode privilege’: Australia edges towardsUK and US levels of inequality. The Sydney Morning Herald, December 12. [Google Scholar]

- Trounstine, Jessica. 2023. You Won’t be My Neighbor: Opposition to High Density Development. Urban Affairs Review 59: 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troy, Laurence, Bill Randolph, Simon Pinnegar, Laura Crommelin, and Hazel Easthope. 2020. Vertical sprawl in the Australian city: Sydney’s high-rise residential development boom. Urban Policy and Research 38: 18–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, Ronald K., Roberta Ryan, Alex Lawrie, Bligh Grant, Xianming Meng, Peter Walsh, Alan Morris, and Chris Riedy. 2020. Global city Sydney. Progress in Planning 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiesel, Ilan, Fanqi Liu, and Caitlin Buckle. 2018. Locational disadvantage and the spatial distribution of government expenditure on urban infrastructure and services in metropolitan Sydney (1988–2015). Geographical Research 56: 285–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, Oren, and David Hedgcock. 1993. Urban social sustainability: The planning of an Australian city. Cities 10: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yiftachel, Oren. 1998. Planning and social control: Exploring the dark side. Journal of Planning Literature 12: 395–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).