How Do Gendered Labour Market Trends and the Pay Gap Translate into the Projected Gender Pension Gap? A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries with Low, Middle and High GPGs

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Socio-Economic Context

2.1. Gender Gaps in the Labour Market

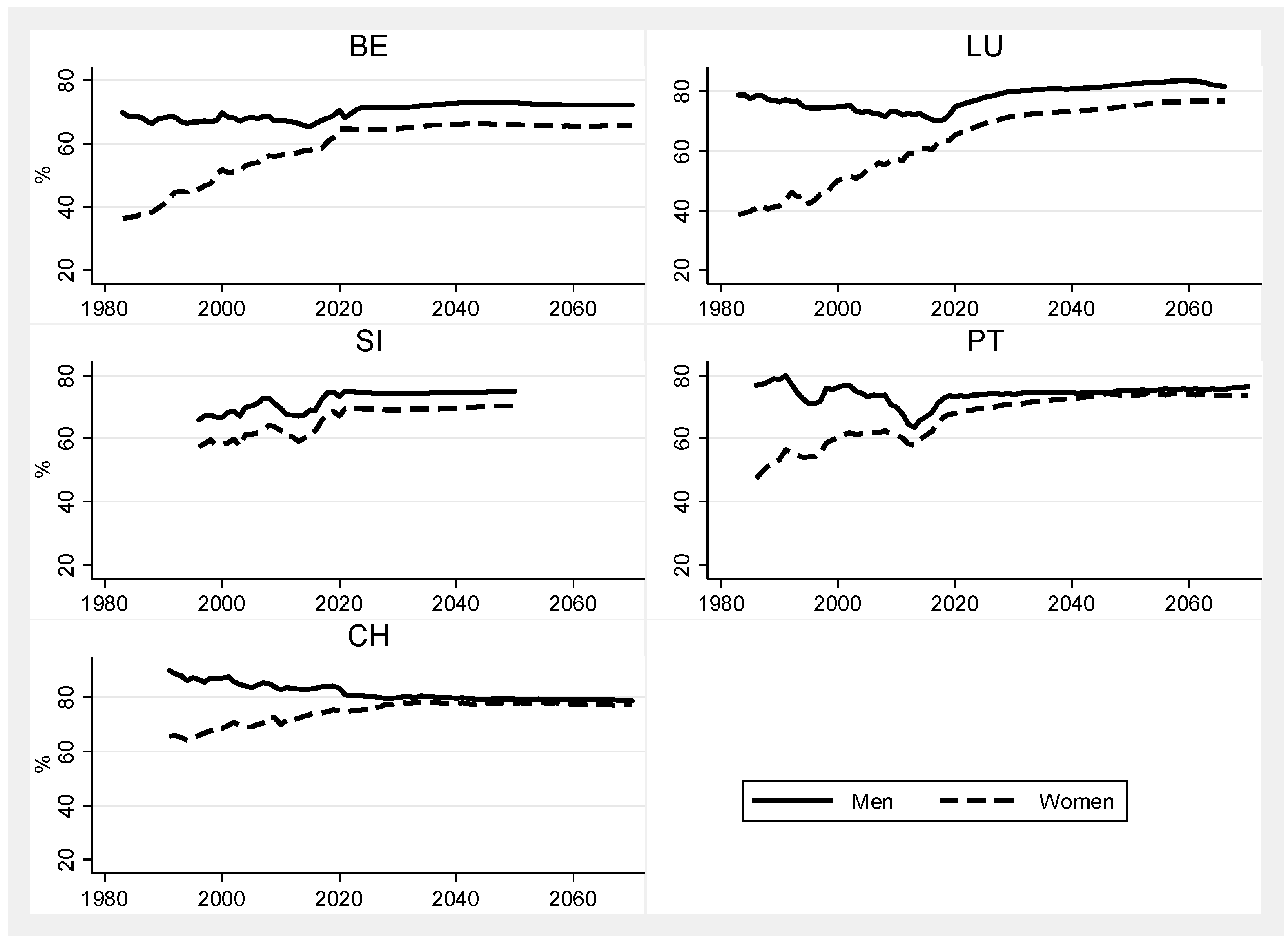

2.2. Gender Difference in Employment Rates

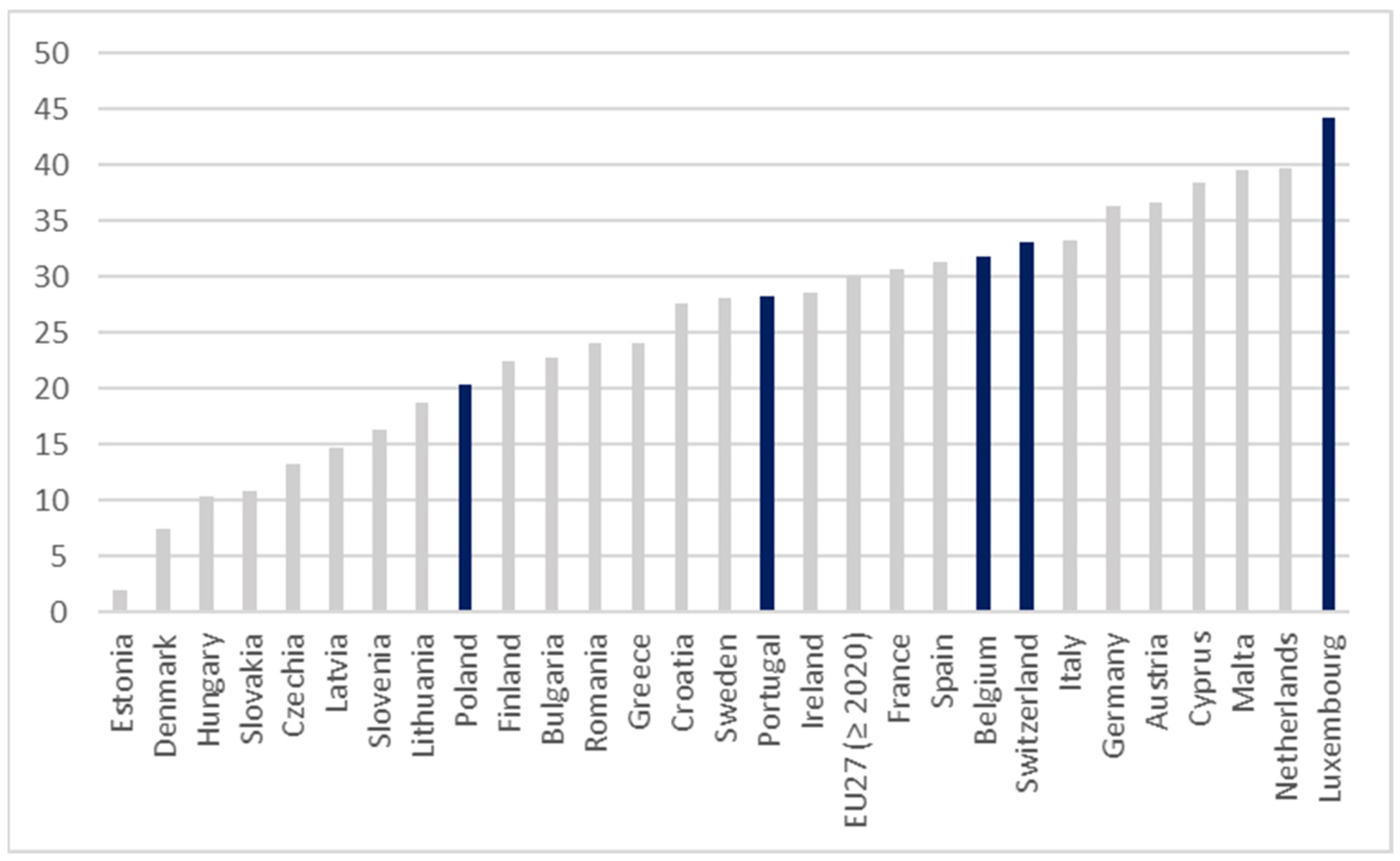

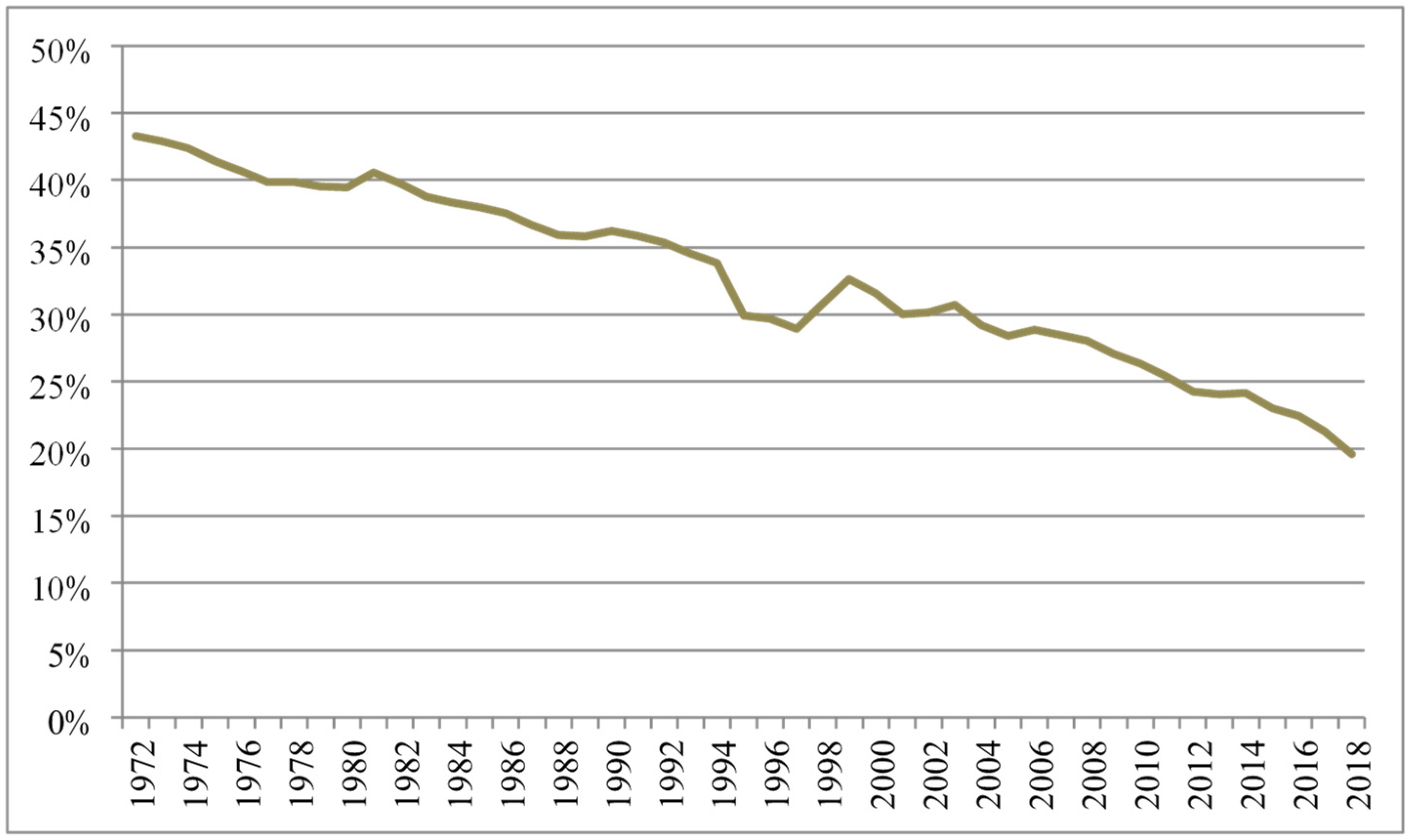

2.3. Gender Difference in Wages

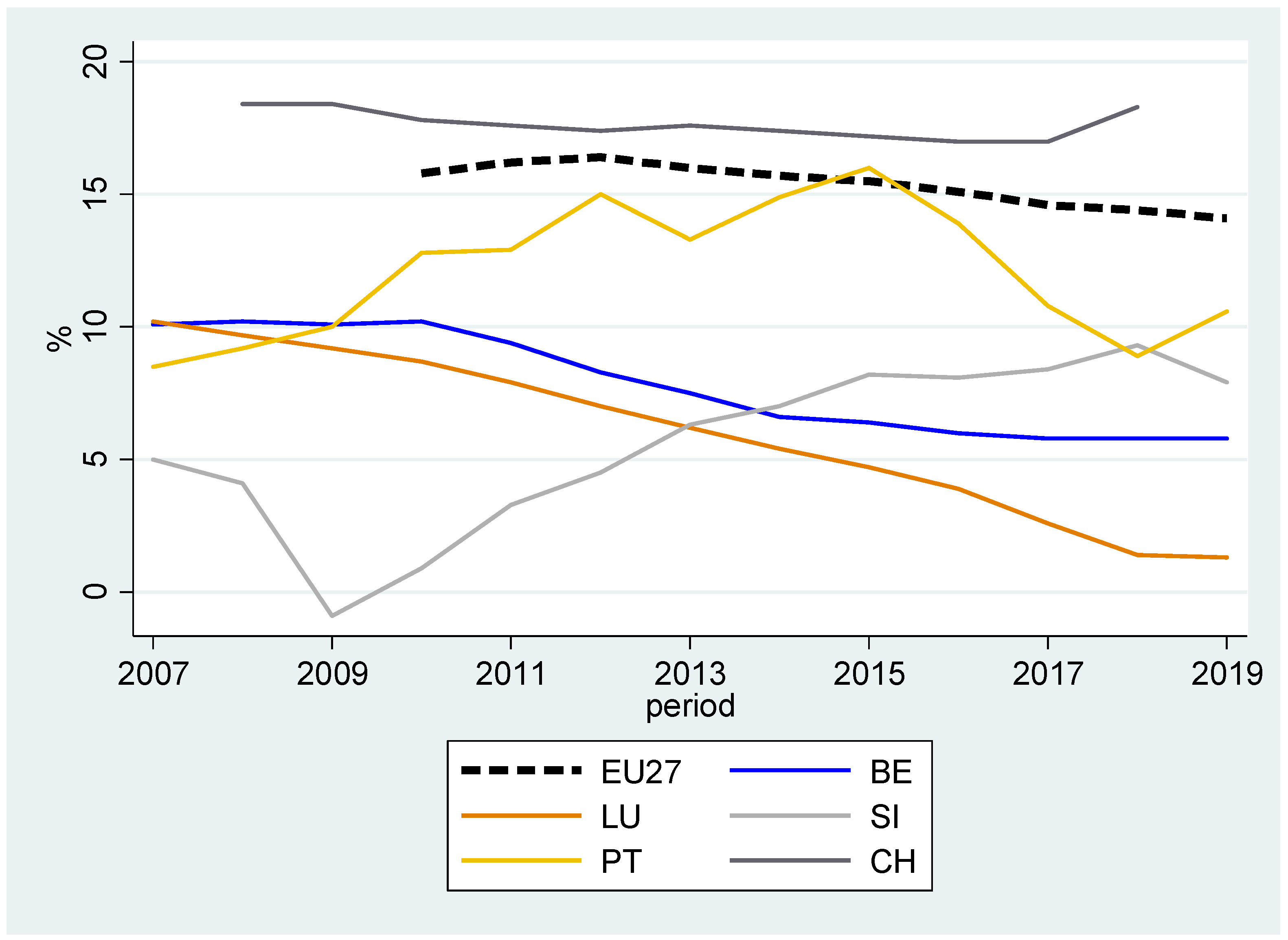

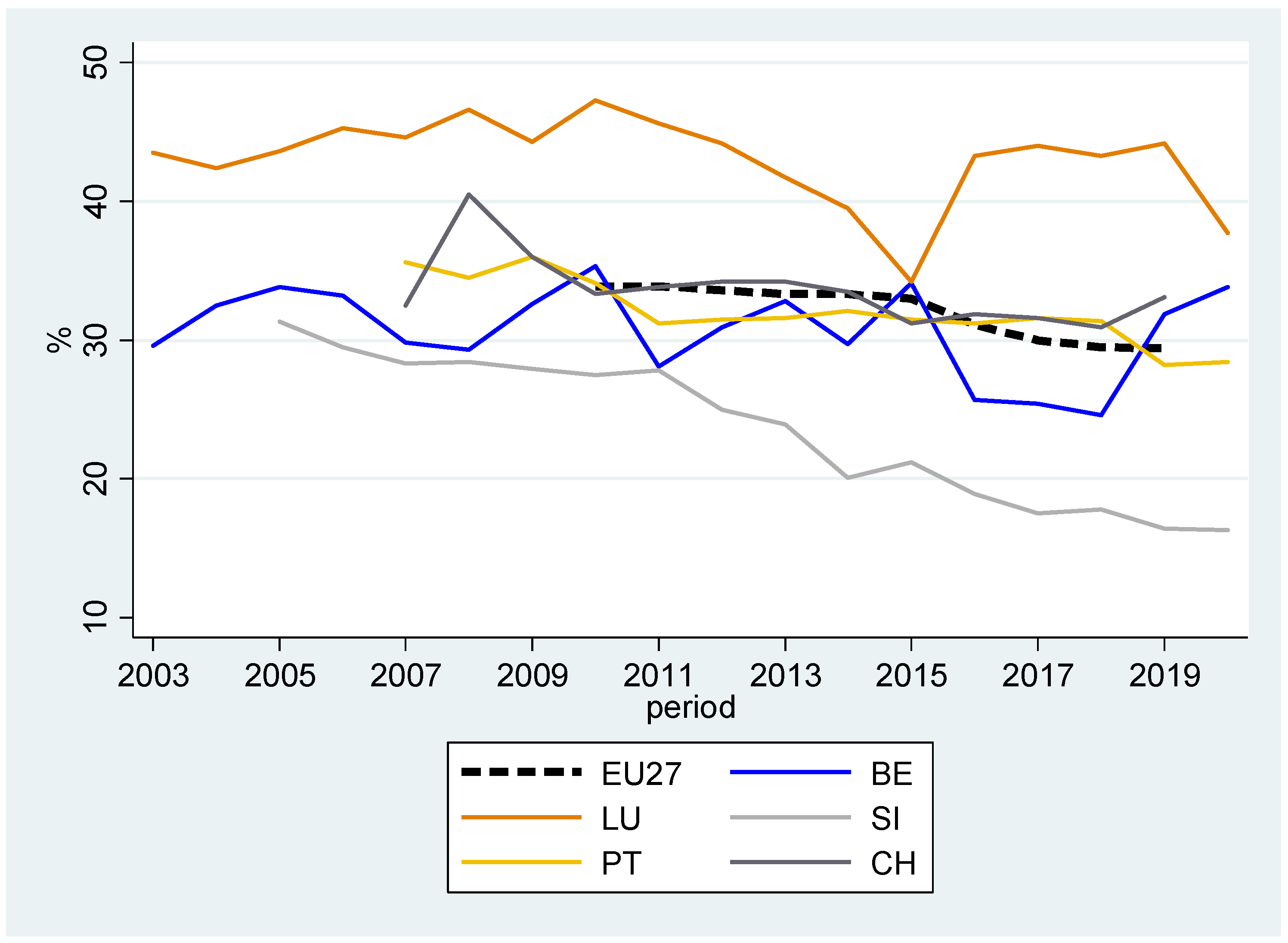

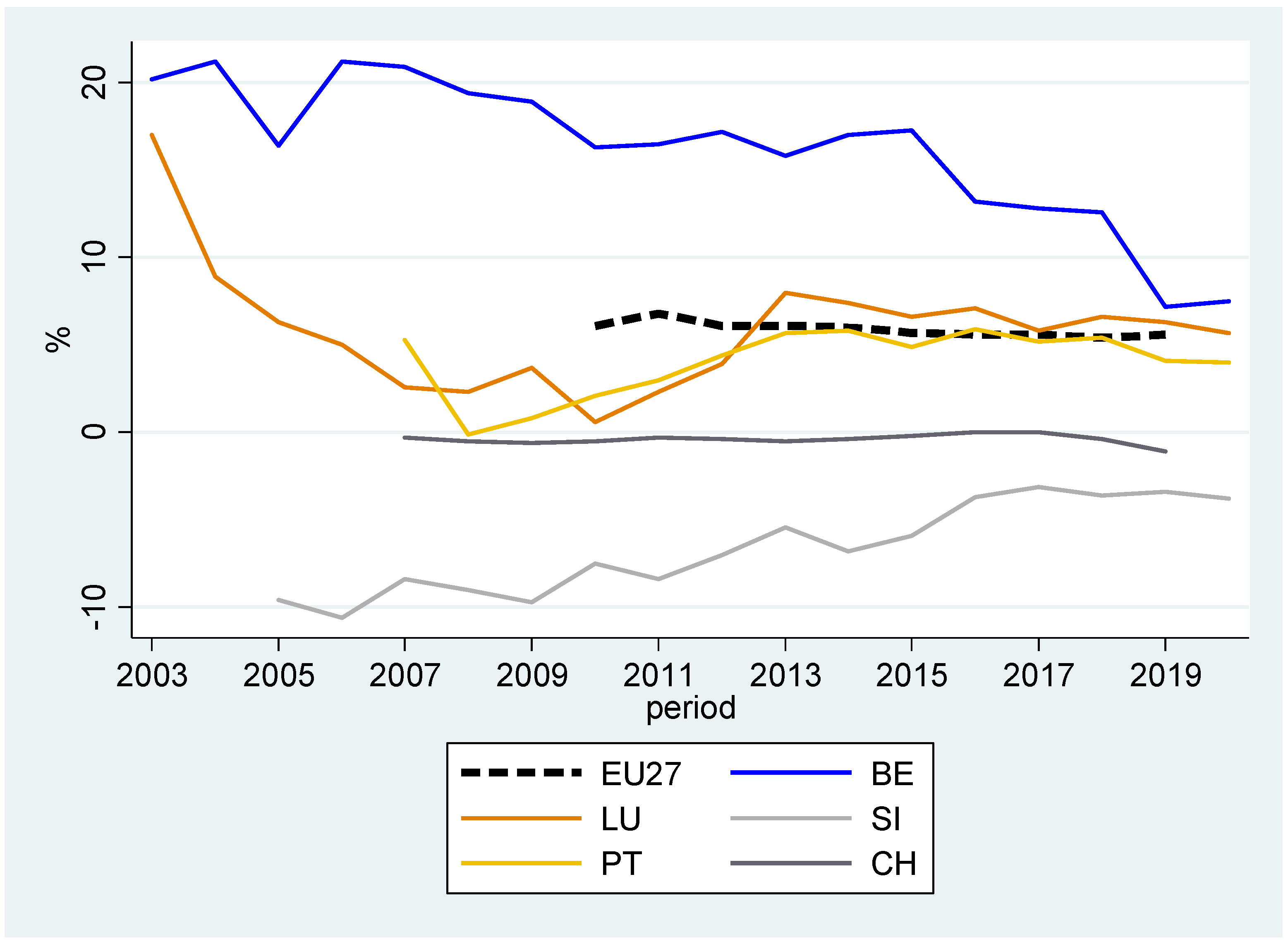

2.4. Recent Evolution of the Gender Pension Gap

3. Pension Regulations

4. Methodology and Pension Models

4.1. Variant GPG Definitions and Alternative Scenarios

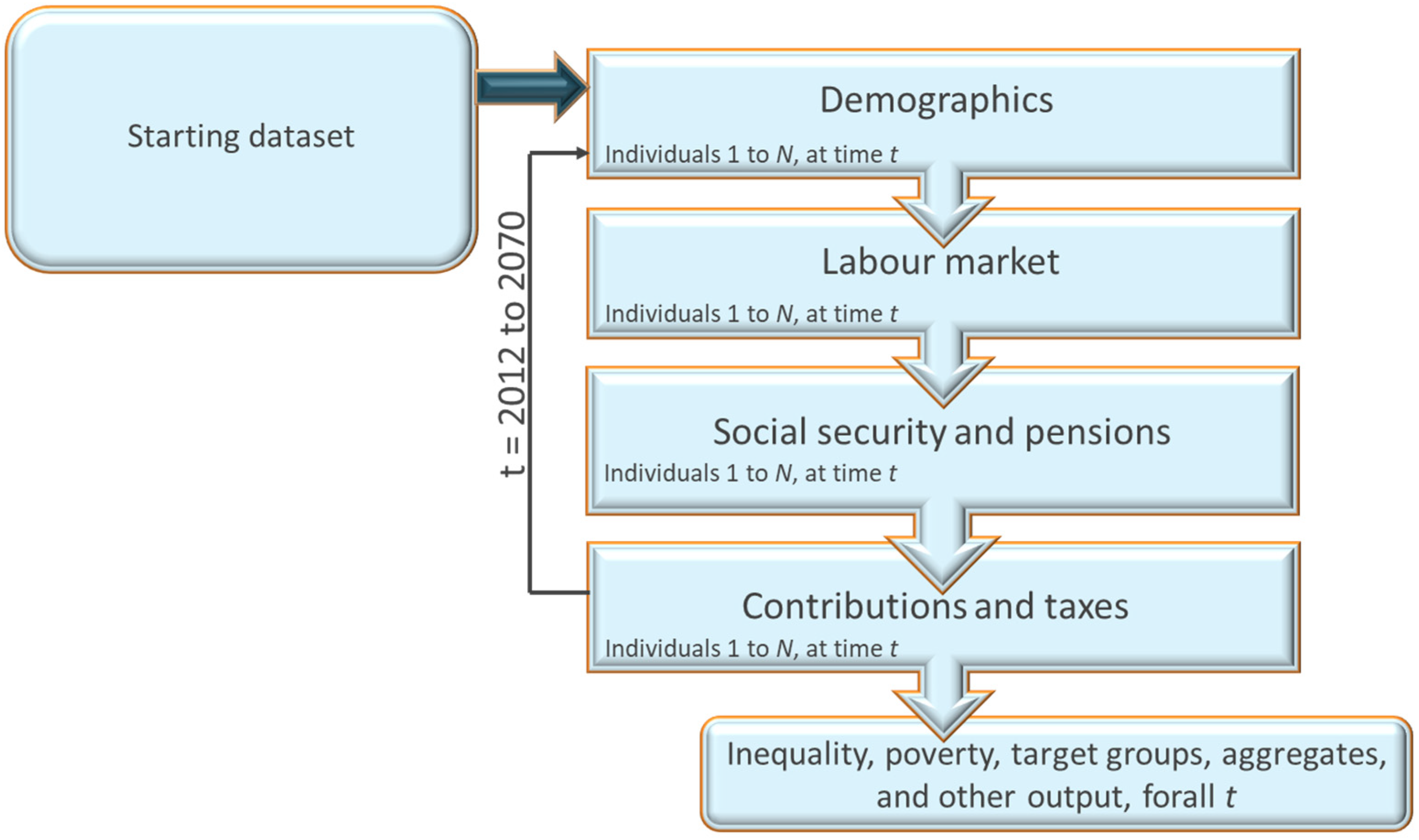

4.2. Microsimulation Modelling Framework

5. Results

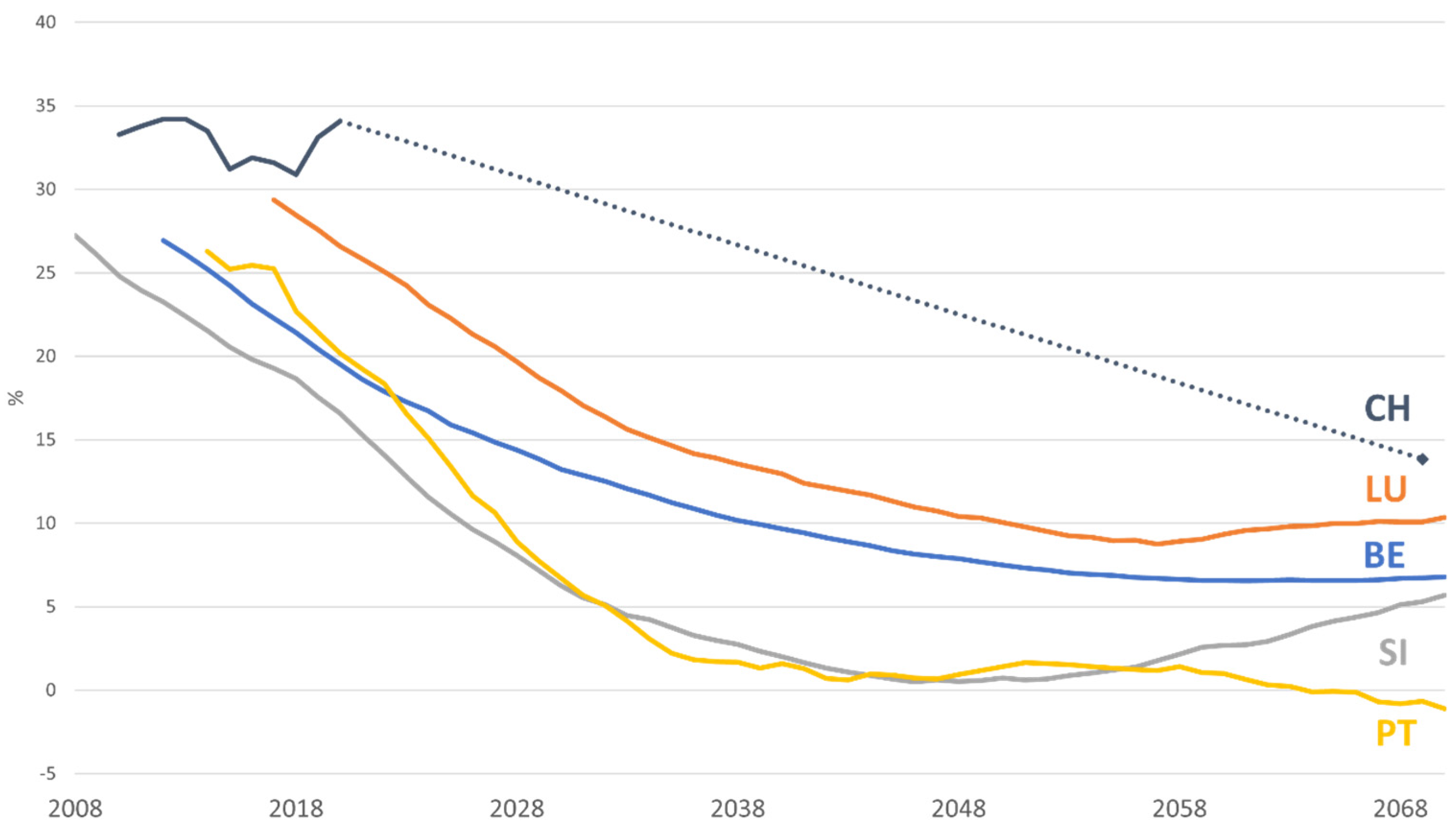

5.1. Base-Scenario Results

5.2. Variants and Alternative Scenarios

5.2.1. GPG and the Coverage Gap

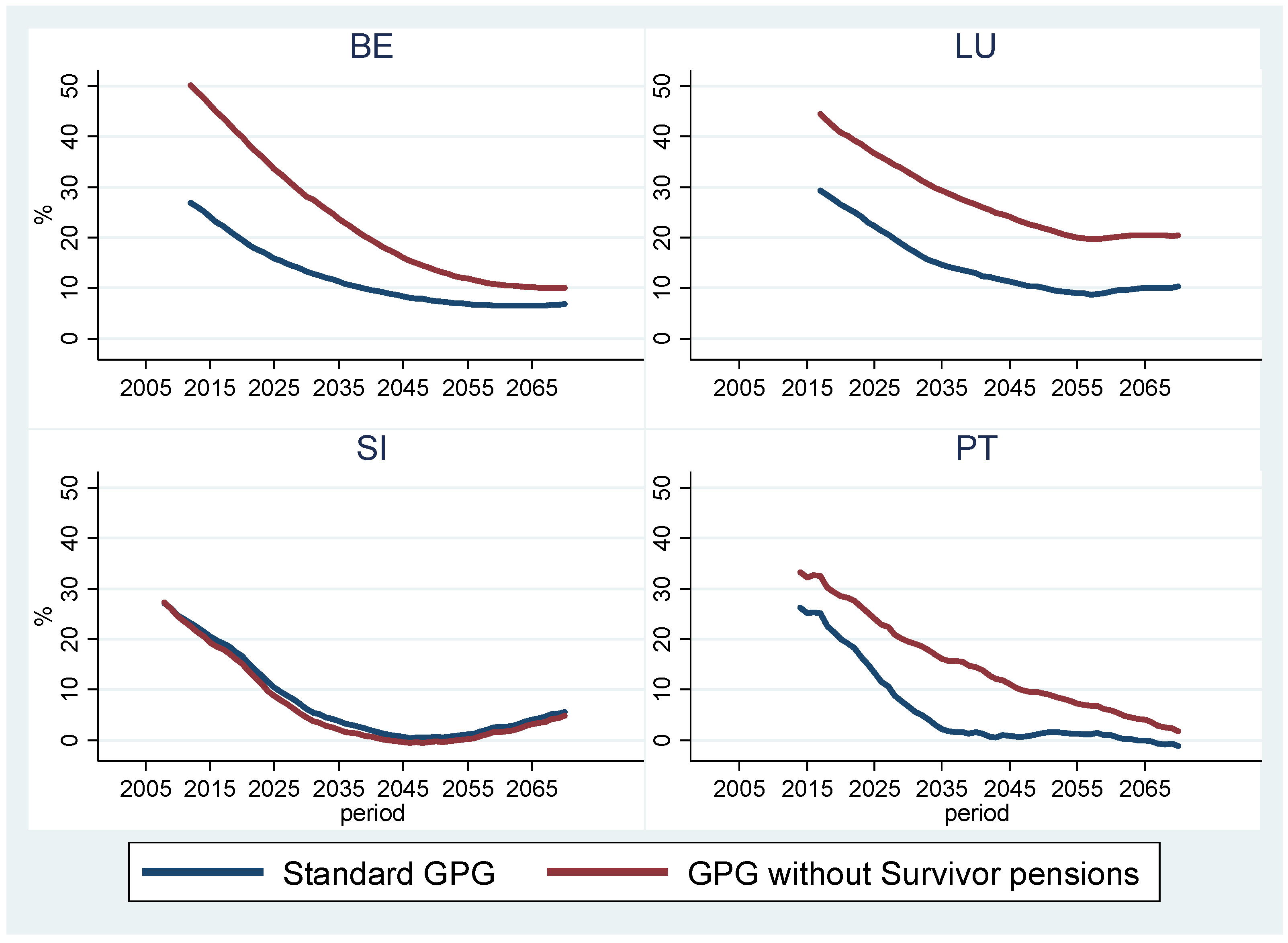

5.2.2. Impact of Survivors’ Pension

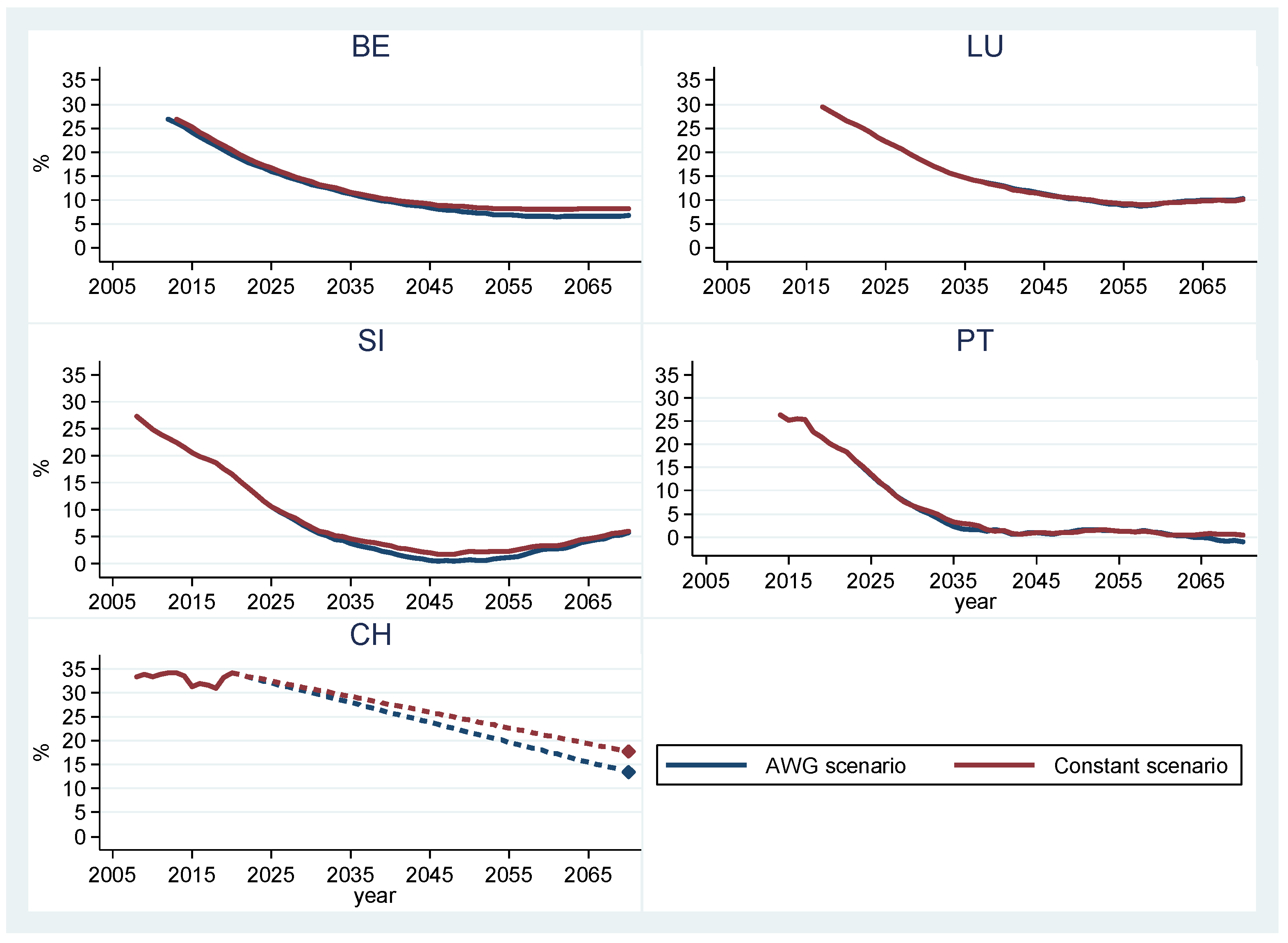

5.2.3. GPG When Assuming That Current Labour Market Outcomes Are Kept Constant

5.2.4. Gender Pension Gap Projections When Equalising Labour Market Status and Pay

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Country | Aggregate Replacement Rate (1) | Retirement Ages | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | F | Early (2) | Normal (3) | Future (3) | |

| EU27 | 0.56 | 0.53 | |||

| BE | 0.47 | 0.46 | 63 | 65 | 67 |

| LU | 0.99 | 0.95 | 62 | 62 | 62 |

| SI | 0.43 | 0.42 | 60 | 62 | 62 |

| PT | 0.67 | 0.64 | 62 | 65.3 | 68 |

| CH | 0.55 | 0.57 | 63 | 65 (M), 64 (F) | 65 (M), 64 (F) |

Appendix B. A Discussion of Dynamic Microsimulation of Pensions

| 1 | The Gender Pension Gap (GPG) measures the relative difference between the pensions of women and men. In a general form, the GPG(l, x) can be written as ; usually l is the mean of the variable of interest, x, e.g., gross pension income, though l can be any measure of location. |

| 2 | The official name is the Working Group on Ageing Populations and Sustainability of the Economic Policy Committee. |

| 3 | Further details can be found in the national reports: Dekkers and Van den Bosch (2021), for Belgium; Liégeois (2021), for Luxembourg; Moreira and Wall (2021), for Portugal; Kump and Stropnik (2021), for Slovenia, and Kirn and Bauman (2021), for Switzerland. |

| 4 | Gender pay gap in unadjusted form in industry, construction, and services (except public administration, defence, compulsory social security). Source: Eurostat, EARN_GR_GPGR2. This indicator reflects the difference between average hourly earnings of male and female employees working in firms with at least 10 employees, expressed as a percentage of the former. |

| 5 | Indeed, women already are more likely than men to provide informal care (OECD 2020, p. 3) and they provide more hours of informal care. As informal care is often accompanied by a reduction or abandonment of professional activity by the caregiver (Ciccarelli and Van Soest 2018; European Commission and Social Protection Committee 2021a, pp. 83–84), the gender difference in informal care-responsibilities adds to the Gender Pension Gap (Bettio et al. 2013; Burkevica et al. 2015). |

| 6 | https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20200207-1. See also the two most recent Pension Adequacy Reports (European Commission and Social Protection Committee 2018, 2021b), and the 2019 Report on Equality between Women and Men in the EU (European Commission 2019, Figure 6, p. 24). |

| 7 | Third-pillar private pensions are not discussed in this article. |

| 8 | |

| 9 | |

| 10 | This section is based on European Commission and Social Protection Committee (2021c) for the four EU countries, and on Kirn and Bauman (2021) for Switzerland. Note that the state of the various pension systems are being included as they were up to early 2021, analogous to the projections of the AWG. This includes all forward-looking measures that were legislated at the time of our modelling. An example of the latter are the future increases of the pensionable age in Belgium and Portugal and gender-neutral pension calculation rules in Slovenia. |

| 11 | Self-employed people and other non-insured persons can contribute voluntarily. |

| 12 | A special arrangement in the Swiss first-pillar pension is that years of care for children below 16 years are counted as contributory years at a rate of three times the minimum pension. |

| 13 | See European Commission (2021b, Figure 30, p. 77). Figures not available for Switzerland. |

| 14 | A particular issue in this context is the decision to retire. In the Slovenian model, individuals most often retire as soon as they are eligible, but they can decide to work up to 3 years longer (based on the probability). In the other models, however, the retirement decision before the statutory retirement age (i.e. early retirement) is mostly the negative result of the labour market equations, i.e., follows from not remaining in the labour market. Once an individual ceases to work at an older age, which is the result of the combination of behavioural equations and alignment tables by age and gender, then the a priori risk of entering into one of the alternative states (unemployment, disability, etc.) becomes very low if he or she is eligible for retirement, with the result that he or she will very likely retire. At the statutory retirement age, all individuals will by definition enter retirement. |

| 15 | Figures for 2019. Eurostat, table “lfsa_eppgacob”. |

| 16 | Each month counts towards the minimum contributory period as soon as 64 h of work have been registered. Furthermore, “surplus” hours worked can be transferred from one month to the next. Therefore, if working 20% of a full time job, one month of every second month counts as a contributory period. Finally, contributory periods include unemployment, registered care periods, and maternity leave. |

| 17 | In 2018, expenditures on old-age and survivor pensions were equal to 9.6% and 1.6% GDP in the EU-27 as a whole (European Commission and Social Protection Committee 2021b, p. 35). |

| 18 | The impact of survivors’ pension could not be determined in the model for Switzerland. |

| 19 | Do note that this scenario does not mean that individuals remain in the state that they occupy in 2021, but rather that the proportional sizes of the various labour market states remain at their 2021 levels. In the reference scenario, the proportional sizes of the various (labour market) states by age and gender change over time. For example, the activity rate among women increases towards that of men; unemployment rates decrease, etc. All these developments are blocked in the constant scenario. However, even though the proportional sizes of the various categories remain constant, individuals still move from one state to another. |

| 20 | For Portugal, only private employment and self-employment rates are equalised. The relative shares of public workers and civil servants remain unchanged (Moreira and Wall 2021). |

References

- Arcanjo, Manuela. 2019. Retirement Pension Reforms in Six European Social Insurance Schemes between 2000 and 2017: More Financial Sustainability and More Gender Inequality? Social Policy and Society 18: 501–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arza, Camila. 2007. Changing European welfare: The new distributional principles of pension policy. In Pension Reform in Europe. London: Routledge, pp. 125–47. [Google Scholar]

- Bettio, Francesca, Platon Tinios, and Gianni Betti. 2013. The Gender Gap in Pensions in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn. 2017. The gender wage gap. Journal of Economic Literature 55: 789–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bonnet, Carole, Jean Michel Hourriez, and Paul Reeve. 2012. Gender Equality in Pensions: What Role for Rights Accrued as a Spouse or a Parent? Population 67: 123–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, Carole, Sophie Buffeteau, and Pascal Godefroy. 2006. Effects of Pension Reforms on Gender Inequality in France. Population 61: 51–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkevica, Ilze, Anne Laure Humbert, Nicole Oetke, and Merle Paats. 2015. Gender Gap in Pensions in the EU: Research Note to the Latvian Presidency. Vilnius: The European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE). [Google Scholar]

- Chłoń-Domińczak, Agnieszka. 2017. Gender Gap in Pensions: Looking Ahead. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Ciccarelli, Nicoléa, and Arthur Van Soest. 2018. Informal Caregiving, Employment Status and Work Hours of the 50+ Population in Europe. De Economist 166: 363–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Conseil Supérieur des Finances. 2021. Comité d’Etude sur le Veillissement. Rapport Annuel. Brussels: Federal Planning Bureau, Available online: https://www.plan.be/uploaded/documents/202107080852050.REP_CEVSCVV2021_12466_F.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Cremer, Helmuth, and Pierre Pestieau. 2003. Social insurance competition between Bismarck and Beveridge. Journal of Urban Economics 54: 181–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dekkers, Gijs, and Karel Van den Bosch. 2021. Projections of the Gender Pension Gap in Belgium using MIDAS. Project MIGAPE Work Package 3. Brussels: Belgian Federal Planning Bureau, Available online: http://www.migape.eu/future.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Dekkers, Gijs, Hermann Buslei, Maria Cozzolino, Raphael Desmet, Johannes Geyer, Dirk Hofmann, Michele Raitano, Victor Steiner, Paola Tanda, Simone Tedeschi, and et al. 2010. The flip side of the coin: The consequences of the European budgetary projections on the adequacy of social security pensions. European Journal of Social Security 12: 94–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, Gijs, Raphael Desmet, Ádám Rézmovits, Olle Sundberg, and Krisztián Tóth. 2015a. On Using Dynamic Microsimulation Models to Assess the Consequences of the AWG Projections and Hypotheses on Pension Adequacy: Simulation Results for Belgium, Sweden and Hungary. Budapest: Federal Planning Bureau and the Central Administration of National Pension Insurance (ONYF), Available online: https://www.plan.be/admin/uploaded/201506121351500.REP_SIMUBESEHU0515_11026.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Dekkers, Gijs, Raphael Desmet, Nicole Fasquelle, and Saskia Weemaes. 2015b. The social and budgetary impacts of recent social security reform in Belgium. In The Young and the Elderly at Risk: Individual Outcomes and Contemporary Policy Challenges in European Societies. Edited by Ioana Salagean, Catalina Lomos and Anne Hartung. Cambridge: Intersentia, pp. 129–58. [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers, Gijs, Riccardo Conti, Raphael Desmet, Olle Sundberg, and Karel Van den Bosch. 2018. What Are the Consequences of the AWG 2018 Projections and Hypotheses on Pension Adequacy? Simulations for Three EU Member States. Report Federal Planning Bureau 11732. Available online: https://www.plan.be/admin/uploaded/201807181105000.REP_AWG2018pension_11732.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Ebbinghaus, Bernhard. 2021. Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Social Policy & Administration 55: 440–55. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2012. White Paper: An Agenda for Adequate, Safe and Sustainable Pensions, COM(2012) 55 Final. Brussels: European Commission, Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:52012DC0055&from=en (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission. 2019. 2019 Report on Equality between Women and Men in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2020. The 2021 Ageing Report: Underlying Assumptions & Projection Methodologies. European Economy Institutional Papers 142. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/economy-finance/ip142_en.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission. 2021a. Gender Pay Gap Statistics. Eurostat: Statistics Explained. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Gender_pay_gap_statistics#Gender_pay_gap_much_lower_for_young_employees (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission. 2021b. The 2021 Ageing Report. Economic and Budgetary Projections for the EU Member States (2019–2070). European Economy Institutional Papers 148. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/publications/2021-ageing-report-economic-and-budgetary-projections-eu-member-states-2019-2070_en (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission. 2022. Gender Pension Gap by Age Group. Available online: https://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_pnp13&lang=en (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission and Social Protection Committee. 2018. Pension Adequacy Report 2018. Current and Future Income Adequacy in Old Age in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, vol. 1. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission and Social Protection Committee. 2021a. Long-Term Care Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission and Social Protection Committee. 2021b. Pension Adequacy Report 2021, Vol. I. Current and Future Income Adequacy in Old Age in the EU. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4ee6cadd-cd83-11eb-ac72-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- European Commission and Social Protection Committee. 2021c. Pension Adequacy Report 2021, Vol. II. Country Profiles. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/4849864a-cd83-11eb-ac72-01aa75ed71a1/language-en/format-PDF/source-search (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Fransen, Eva, Janneke Plantenga, and Jan Dirk Vlasblom. 2012. Why do women still earn less than men? Applied Economics 44: 4343–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frericks, Patricia, Trudy Knijn, and Robert Maier. 2009. Pension Reforms, Working Patterns and Gender Pension Gaps. Europe Gender, Work and Organization 16: 710–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FSO. 2020. Erwerbsbeteiligung der Frauen 2010–2019. Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/arbeit-erwerb/erwerbstaetigkeit-arbeitszeit/merkmale-arbeitskraefte/vollzeit-teilzeit.assetdetail.14941826.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- FSO. 2021. Entwicklung der Arbeitszeit 2010–2020. Neuchâtel: Swiss Federal Statistical Office. Available online: https://www.bfs.admin.ch/asset/de/2098-2000 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Goldin, C. 2014. A grand gender convergence. The American Economic Review 104: 1091–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Halvorsen, Elin, and Axel West Pedersen. 2019. Closing the gender gap in pensions. A microsimulation analysis of the Norwegian NDC pension system. Journal of European Social Policy 29: 130–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Herd, Pamela. 2009. Women, Public Pensions, and Poverty: What Can the United States Learn from Other Countries? Journal of Women, Politics & Policy 30: 301–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute for the Equality of Women and Men. 2021. De Loonkloof Tussen Vrouwen en Mannen in België. IGVN Rapport. Available online: https://igvm-iefh.belgium.be/nl/publicaties/de_loonkloof_tussen_vrouwen_en_mannen_in_belgie_rapport_2021 (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Jolly, Richard. 2014. Inequality And ageing. In Facing the Facts: The Truth about Ageing and Development. London: Age International. [Google Scholar]

- Kirn, Tanja, and Nicolas Bauman. 2021. Project MIGAPE Work Package 3: Results of the Dynamic Simulations for Switzerland. Mimeo MIGAPE Project. March 29. Available online: http://www.migape.eu/future.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Kolmar, Martin. 2007. Beveridge versus Bismarck public-pension systems in integrated markets. Regional Science and Urban Economics 37: 649–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kump, Nataša, and Nada Stropnik. 2021. Projections of the Gender Pension Gap in Slovenia Using DYPENSI. MIGAPE Work Package 3. Ljubljana: Institute for Economic Research, Available online: http://www.migape.eu/future.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Leitner, Sigrid. 2001. Sex and gender discrimination within EU pension systems. Journal of European Social Policy 11: 99–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lequien, Laurent. 2012. The Impact of Parental Leave Duration on Later Wages. Annals of Economics and Statistics 107/108: 267–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liégeois, Philippe. 2021. Projections of the Gender Pension Gap in Luxembourg Using LU-MIDAS 2020. MIGAPE Work Package 3. Esch-sur-Alzette: Luxembourg Institute for Socio-Economic Research (LISER), Available online: http://www.migape.eu/future.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- Möhring, Katja. 2018. Is there a motherhood penalty in retirement income in Europe? The role of lifecourse and institutional characteristics. Ageing & Society 38: 2560–89. [Google Scholar]

- Moreira, Amílcar, and Karen Wall. 2021. Projections of the Gender Pension Gap in Portugal Using DYNAPOR. MIGAPE Work Package 3. Lisbon: Institute of Social Sciences, University of Lisbon, Available online: http://www.migape.eu/future.html (accessed on 8 July 2022).

- OECD. 2012. Closing the Gender Gap: Act Now. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2020. Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Care Workers for the Elderly. OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. 2021. Pensions at a Glance 2021. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staff, Jeremy, and Jeylan T. Mortimer. 2012. Explaining the motherhood wage penalty during the early occupational career. Demography 49: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thévenon, Olivier, and Anne Solaz. 2013. Labour Market Effects of Parental Leave Policies in OECD Countries. OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 141. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- van Hek, Margriet, Gerbert Kraaykamp, and Maarten Wolbers. 2016. Comparing the gender gap in educational attainment: The impact of emancipatory contexts in 33 cohorts across 33 countries. Educational Research and Evaluation 22: 260–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veremchuck, Anna. 2020. Gender Gap in Pension Income: Cross-Country Analysis and Role of Gender Attitudes. Kiel: ZBW-Leibniz-Informationszentrum Wirtschaft, Available online: http://zbw.eu/econis-archiv/bitstream/11159/4575/1/febawb126.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2022).

| Country | Active Persons | Older Persons (Men/Women) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occup | Personal | Public | Occup | Personal | |

| BE | 59.6 | 38 | 98.8/83.1 | 2.4/1.5 | 3.3/1.5 |

| LU | 5.1 | .. | 96.4/92.0 | 9.5/1.6 | 4.2/1.7 |

| SI | 36.5 | 1.4 | 90.2/87.6 | 1.1/0.7 | 1.8/2.1 |

| PT | 3.7 | 4.5 | 87.2/78.8 | ../.. | 0.8/1.0 |

| CH | 56.8/43.2 | .. | 97.6/98.7 | 82.9/69.5 | 45.1/34.9 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dekkers, G.; Van den Bosch, K.; Barslund, M.; Kirn, T.; Baumann, N.; Kump, N.; Liégeois, P.; Moreira, A.; Stropnik, N. How Do Gendered Labour Market Trends and the Pay Gap Translate into the Projected Gender Pension Gap? A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries with Low, Middle and High GPGs. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070304

Dekkers G, Van den Bosch K, Barslund M, Kirn T, Baumann N, Kump N, Liégeois P, Moreira A, Stropnik N. How Do Gendered Labour Market Trends and the Pay Gap Translate into the Projected Gender Pension Gap? A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries with Low, Middle and High GPGs. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(7):304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070304

Chicago/Turabian StyleDekkers, Gijs, Karel Van den Bosch, Mikkel Barslund, Tanja Kirn, Nicolas Baumann, Nataša Kump, Philippe Liégeois, Amílcar Moreira, and Nada Stropnik. 2022. "How Do Gendered Labour Market Trends and the Pay Gap Translate into the Projected Gender Pension Gap? A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries with Low, Middle and High GPGs" Social Sciences 11, no. 7: 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070304

APA StyleDekkers, G., Van den Bosch, K., Barslund, M., Kirn, T., Baumann, N., Kump, N., Liégeois, P., Moreira, A., & Stropnik, N. (2022). How Do Gendered Labour Market Trends and the Pay Gap Translate into the Projected Gender Pension Gap? A Comparative Analysis of Five Countries with Low, Middle and High GPGs. Social Sciences, 11(7), 304. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11070304