Technological Utopias: Loneliness and Rural Contexts in Western Iberia

Abstract

:1. Loneliness and Ageing in Western Iberia

2. Materials, Methods and Settings

3. Definition and Uses of Loneliness and Technologies

3.1. Emotional Loneliness, Social Loneliness

Look, on New Year’s Eve—I really struggled, because that was the first year that I had dinner alone, at home. And I didn’t want to go to somebody else’s—as I said, “I am not going to another family when they are celebrating together, while I do not have a family”(Luz, 71 years old)

There is a poor man living all alone—as there are everywhere. And women do not go to their houses, or they go less often. When a woman is left alone, she always has compaña [company]—all her [female] neighbours and everybody visit and give compaña(Ana, 83 years old)

Back then, when my husband and I were at school, there were thirty-two or thirty-three of us children here. A few of us were from here, others came from a village now abandoned, where there is nobody left (…) And also over there, over there by the rocky hilltops. And from here, you see, there were a few of us… But now there is not a single child left(Luisa, 82 years old)

3.2. Analogue Ageing in Rural Contexts

When my mother died, my father stayed in their home. That’s all he wanted—to stay at home. So the people from Red Cross gave him that gadget in case something happened, which he could wear around his neck. And he never took it off. Back then they used to phone him, too(Rosana, 68 years old)

The television—because you hear it while you are around doing things, cleaning. So you can hear something going on. Different conversations—some you listen to, some you don’t. You want politics, you switch to [channel] six. You want gossip, you switch to [channel] five. You have plenty to choose from, so you don’t waste time(Luz, 71 years old)

Normally, for me, it is the television—I don’t listen to the radio. It helps me escape, it is almost as if I wasn’t alone—others might have also told you this, the television is an ugly machine, whatever, but… It keeps you company. That’s how I feel, and others might have said this already, because this is just the way it is(Julia, 77 years old)

The telly—I have it on all day. The telly, I get up (…) there, it is on. Because the telly, for me—it is my life. I hear the conversations. I’ll tell you this, don’t ask me what I have been watching (…) But the telly is one of the most important things in my house. I tell you, I could not be without it. I could do without a washing machine, but not the telly—I know you won’t believe it(Francisca, 75 years old)

3.3. Limitations to the Introduction of Digital Technology

I often get phone calls, from the bank, or the electricity company, and they say “if you were to move to online [billing] it would be cheaper, I could take these away”. But… How am I going to manage that, at my age?—Me, dealing with online―? Come on, it is too late…(Manuel, 84 years old)

I really do not want it. I can manage the mobile. I can phone… I do not need that WhatsApp, if I need to phone anybody I just do it, I have the numbers written down and that’s it. Because this lassie, she has also put my sons in the mobile too… But I—with things like this—no…(María, 78 years old)

When my daughter is visiting sometimes, I have to say, “Come on, I am going to completely ban mobiles at home—I feel I am talking, and nobody is listening”. We are having a meal, and the first thing people do is put these on the table. Well, I do not think that is right—a meal with friends and the first thing we do is leave these on top of the table(María, 78 years old)

They really should know that you do not—for us, at our age, to put those things… What I mean is, they put the public notices up there instead of—they put them up in WhatsApp. What the heck… They should do the public notices as they used to before, for us old people(Manuel, 84 years old)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

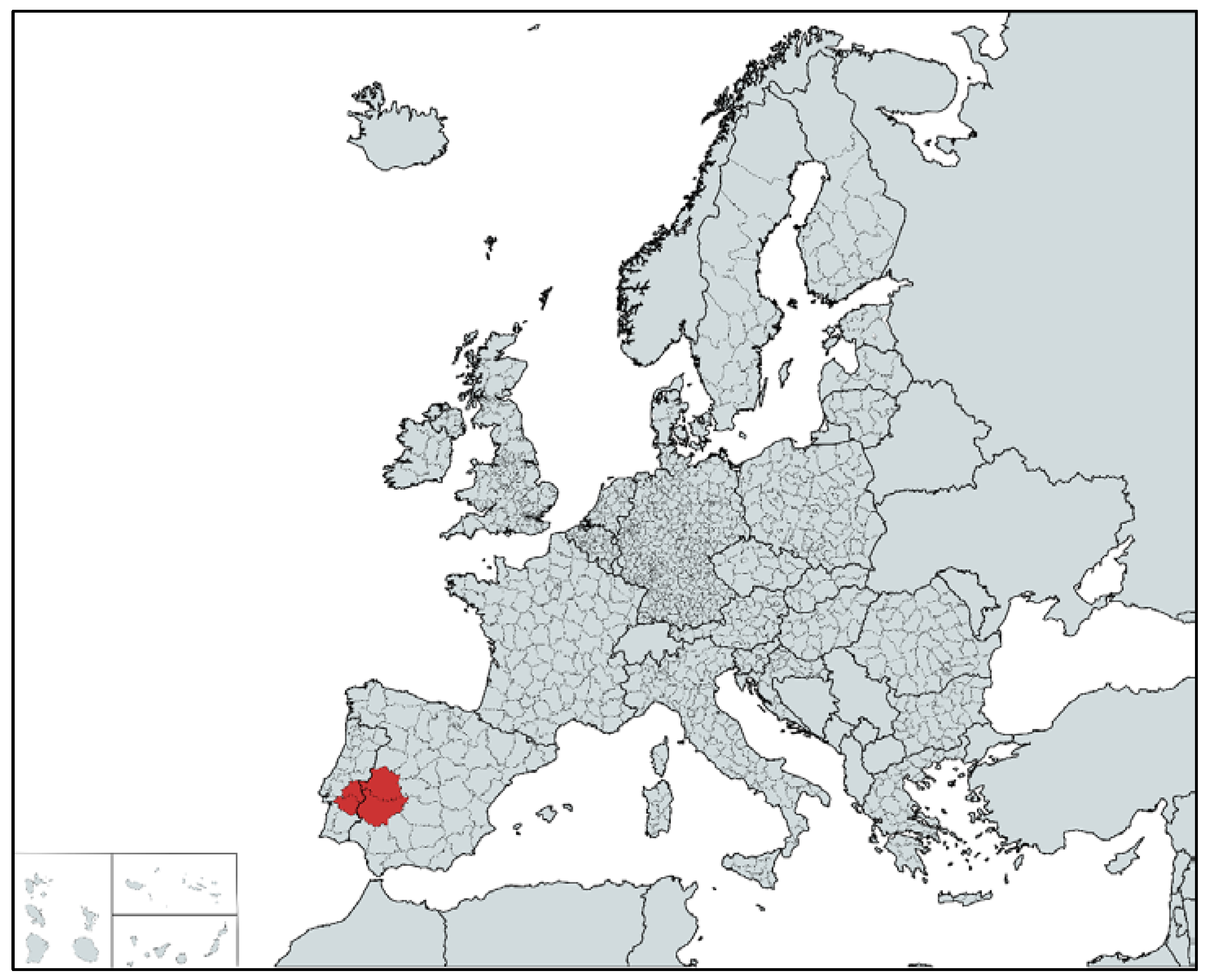

| 1 | In Extremadura, 53% of the population resides in rural municipalities with less than 5000 inhabitants, 22% in intermediate municipalities and 25% in urban municipalities, those with more than 1000 inhabitants. There is a low population density, with large areas below 10 inhabitants/km. This translates into greater investment in all types of health, social and cultural services. In addition, the region’s low industrialisation makes it difficult to create jobs for young people, which again fuels migration. |

| 2 | In this text we understand older people to be the age stage that begins at 65 years old. There is a convention in our context of study that this is the beginning of the elderly, probably related to the age at which workers traditionally retire and can start receiving a pension. We understand that in other cultures and contexts this age may be a little earlier or later than the one chosen, but we believe that it is the one that best fits the old age in our context. |

| 3 | The data that is usually used when talking about loneliness refers to the number of single-person households, giving the idea that living alone in a household would be the same as having feelings of loneliness; something that although we believe may be related, as many previous studies on the subject point out, it does not have to be a defining fact. |

| 4 | In this text we understand ‘rural’ as those municipalities with a population of less than 10,000 inhabitants. According to the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, this type of population can be subdivided into intermediate (those with a population between 2000 and 10,000 inhabitants) or small or rural (with a population of less than 2000 inhabitants). The latter subdivision includes the municipalities where the empirical material used for the development of this article has been collected. |

| 5 | All names of research participants were changed to avoid their identification. |

References

- Aartsen, Marja, and Marja Jylhä. 2011. Onset of loneliness in older adults: Results of a 28 year prospective study. European Journal of Ageing 8: 31–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Allerton, Catherine. 2007. What Does It Mean to Be Alone? In Anthropology of This Century. Edited by Rita Astuti, Jonathan Parry and Charles Stafford. London: Routledge, vol. 18, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci, Toni C., Kristine J. Ajrouch, and Jasmine A. Manalel. 2017. Social Relations and Technology: Continuity, Context, and Change. Innovation in Aging 1: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baecker, Ron, Kate Sellen, Sarah Crosskey, Veronique Boscart, and Barbara Barbosa Neves. 2014. Technology to Reduce Social Isolation and Loneliness. Paper presented at the 16th International ACM SIGACCESS Conference on Computers and Accessibility, Rochester, NY, USA, October 27–34. [Google Scholar]

- Ball, Christopher, Jessica Francis, Kuo Ting Huang, Travis Kadylak, Shelia R. Cotten, and R. V. Rikard. 2019. The Physical–Digital Divide: Exploring the Social Gap Between Digital Natives and Physical Natives. Journal of Applied Gerontology 38: 1167–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barbosa Neves, Barbara, and Fausto Amaro. 2012. Too Old for Technology? How The Elderly Of Lisbon Use And Perceive ICT. The Journal of Communitiy Informatics 8: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa Neves, Barbara, Rachel Franz, Rebecca Judges, Christian Beermann, and Ron Baecker. 2019. Can Digital Technology Enhance Social Connectedness Among Older Adults? A Feasibility Study. Journal of Applied Gerontology 38: 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barnard, Yvonne, Mike D. Bradley, Frances Hodgson, and Ashley D. Lloyd. 2013. Learning to use new technologies by older adults: Perceived difficulties, experimentation behaviour and usability. Computers in Human Behavior 29: 1715–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berg, Turi, Rachel Winterton, Maree Petersen, and Jeni Warburton. 2017. ‘Although we’re isolated, we’re not really isolated’: The value of information and communication technology for older people in rural Australia. Australasian Journal on Ageing 36: 313–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonilla-García, Miguel Ángel, and Ana Delia López-Suárez. 2016. Ejemplificación del proceso metodológico de la teoría fundamentada. Cinta de Moebio 57: 305–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Boyd, Adele, Jonathan Synnott, Chris Nugent, David Elliott, and John Kelly. 2017. Community-based trials of mobile solutions for the detection and management of cognitive decline. Healthcare Technology Letters 4: 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bray, Francesca. 2007. Gender and Technology. Annual Review of Anthropology 36: 37–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Brinkmann, Svend, and Steinar Kvale. 2015. InterViews. In Learning the Craft of Qualitative Research Interviewing. London: SAGE Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Buz Delgado, José. 2013. Envejecimiento y Soledad. La Importancia de Los Factores Sociales. In Por Una Cultura Del Envejecimiento. Edited by M. Cubillo and F. Quintanar. México City: Centro Mexicano Universitario de Ciencias y Humanidades, pp. 271–81. [Google Scholar]

- Cacioppo, John T., and William Patrick. 2008. Loneliness. In Human Nature and the Need for Social Connection. London: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Casamayou, Adriana. 2017. Personas Mayores y Tecnologías Digitales: Desafíos de Un Binomio. Psicología Conocimiento y Sociedad 7: 152–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cayetano Rosado, Moisés. 2006. Extremadura y Alentejo: Del subdesarrollo heredado a los retos del futuro. Revista de Estudios Extremeños 62: 1167–88. [Google Scholar]

- Cayetano Rosado, Moisés. 2011. Emigración exterior de la Península Ibérica durante el desarrollismo europeo. El caso extremeño-alentejano. Revista de Estudios Extremeños 67: 1653–80. [Google Scholar]

- Crewdson, James A. 2016. The Effect of Loneliness in the Elderly Population: A Review. Healthy Aging & Clinical Care in the Elderly 8: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Silva, W.M. Amarasiri, and Jayaprasad Welgama. 2014. Modernization, Aging and Coresidence of Older Persons: The Sri Lankan Experience. Anthropology & Aging 35: 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Donio-Bellegarde, Mónica. 2017. La Soledad de Las Mujeres Mayores Que Viven Solas. Universitat de Valencia: Available online: http://roderic.uv.es/handle/10550/58362 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Douglas, Mary. 1996. Natural Symbols. Explorations in Cosmology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton, Willian H., and Bianca C. Reisdorf. 2019. Cultural divides and digital inequalities: Attitudes shaping Internet and social media divides. Information, Communication & Society 22: 18–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emans, Ben. 2004. Interviewing. Theory, Techniques and Training. London: Routedge. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat. 2020. Ageing Europe. Looking at the Lives of Older People in the EU. Louxembourg: Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3217494/11478057/KS-02-20-655-EN-N.pdf/9b09606c-d4e8-4c33-63d2-3b20d5c19c91?t=1604055531000 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Franklin, Adrian, Barbara Barbosa Neves, Nicholas Hookway, Roger Patulny, Bruce Tranter, and Katrina Jaworski. 2019. Towards an understanding of loneliness among Australian men: Gender cultures, embodied expression and the social bases of belonging. Journal of Sociology 55: 124–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammersley, Martom, and Paul Atkinson. 1994. Etnografía. In Métodos de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Byung-Chul. 2020. La Desaparición de los Rituales. Barcelona: Herder Editorial. [Google Scholar]

- Happio-Kirk, Laura, Charlotte Hawkins, Maya de Vries-Kedem, and Daniel Miller. 2020. Ageing with Smartphones ‘from below’: Insights from Japan, Uganda, Al-Quds and Ireland. Paper presented at the Selecxted Papers of #AoIR2020: The 21st Annual Conference of the Association of Internat Resera-chers. Virtual Event. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Niail, Lucas Introna, and Marcia Tavares Smith. 2019. Ensembles of Practice: Older Adults, Technology, and Loneliness & Social Isolation in Rural Settings. Paper presented at the 52nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Maui, HI, USA, January 8–11; vol. 6, pp. 4287–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt-Lunstad, Julianne, Timothy B. Smith, Mark Baker, Tyler Harris, and Davis Stephenson. 2015. Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science 10: 227–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística de España. 2019. Estadística del Padrón Continuo. Available online: https://www.ine.es/dyngs/INEbase/es/operacion.htm?c=Estadistica_C& cid=1254736177012& menu=ultiDatos& idp=1254734710990 (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Instituto Nacional de Estadistica de Portugal. 2021. Índice de Envelhecimento por Local de Residência. Available online: https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpid=INE& xpgid=ine_indicadores& indOcorrCod=0011187&contexto=bd& selTab=tab2 (accessed on 17 February 2021).

- Liddle, Jennifer, Nicole Pitcher, Kyle Montague, Barbara Hanratty, Holly Standing, and Thomas Scharf. 2020. Connecting at local level: Exploring opportunities for future design of technology to support social connections in age-friendly communities. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 5544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marston, Hammah Ramsden, Rebecca Genoe, Shannon Freeman, Cory Kulczycki, and Charles Musselwhite. 2019. Older Adults’ Perceptions of ICT: Main Findings from the Technology in Later Life (TILL) Study. Healthcare 7: 86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martín Martín, Francisco Marcos. 2017. Habilidades comunicativas como condicionantes en el uso de las TIC en personas adultas mayores. International Journal of Educational Research and Innovation (IJERI) 8: 220–32. [Google Scholar]

- McHugh Power, Joanna E., Caoimbe Hannigan, Sile Carney, and Brian A. Lawlor. 2017. Exploring the meaning of loneliness among socially isolated older adults in rural Ireland: A qualitative investigation. Qualitative Research in Psychology 14: 394–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez Álvarez-Dardet, Susana, Bárbara Lorence Lara, and Javier Pérez-Padilla. 2020. Older adults and ICT adoption: Analysis of the use and attitudes toward computers in elderly Spanish people. Computers in Human Behavior 110: 106377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Daniel. 2015. The Tragic Denouement of English Sociality. Cultural Anthropology 30: 336–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muñoz-Rodríguez, José Manuel, María José Hernández-Serrano, and Carmen Tabernero. 2020. Digital identity levels in older learners: A new focus for sustainable lifelong education and inclusion. Sustainability 12: 657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neumann, Cecilie Basberg, and Iver B. Neumann. 2018. Interview Techniques. In Power, Culture and Situated Research Methodology. Autobiography, Field, Text. Edited by Cecilie Basberg Neumann and Iver B. Neumann. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Nikou, Shahrokh, Wirawan Agahari, Wally Keijzer-Broers, and Mark de Reuver. 2020. Digital healthcare technology adoption by elderly people: A capability approach model. Telematics and Informatics 53: 101315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowell, Lorelli S., Jill M. Norris, Deborah E. White, and Nancy J. Moules. 2017. Thematic Analysis: Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 16: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa-de Silva, Chiklako, and Michelle Parsons. 2020. Toward an anthropology of loneliness. Transcultural Psychiatry 57: 613–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Páez, Dario, María Ángeles Bilbao, Magdalena Bobowik, Myriam Campos, and Nekane Basabe. 2011. Merry Christmas and Happy New Year! The impact of Christmas rituals on subjective well-being and family’s emotional climate. Revista de Psicologia Social 26: 373–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, Michelle Anne. 2020. Being unneeded in post-Soviet Russia: Lessons for an anthropology of loneliness. Transcultural Psychiatry 57: 635–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peacock, James Lowe. 1986. Method. In The Anthropological Lens. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peplau, Letitia Anne, and Daniel Perlman. 1982. Loneliness: A Sourcebook of Current Theory, Research and Therapy. New York: John Willey and Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez García, Ruben, Leticia Cano López, Ana María Llera De La Torre, Celia María Morales Córdoba, Ana Belén Parra Díaz, and Agustín Aibar Almazán. 2019. El uso de las nuevas tecnologías para evitar la soledad de las personas mayores de 80 años. Paraninfo Digital 30: e30084. [Google Scholar]

- Pettigrew, Simone, and Michelle Roberts. 2008. Addressing loneliness in later life. Aging & Mental Health 12: 302–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinilla, Vicente, and Luis Antonio Sáez. 2016. La Despoblación Rural En España: Génesis De Un Problema Y Políticas Innovadoras. Centro de Estuios Sobre Despoblación y Desarrollo de Áreas Rurales: Available online: https://www.roldedeestudiosaragoneses.org/wp-content/uploads/Informes-2017-2-Informe-SSPA1_2017_2.pdf (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Pinquart, Martin, and Silvia Sörensen. 2007. Correlates of physical health of informal caregivers: A meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 62: P126–P137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pope, Catherine. 2000. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ 320: 114–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portacolone, Elena. 2015. Older Americans Living Alone: The Influence of Resources and Intergenerational Integration on Inequality. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 44: 280–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, Susan J. 2020. Images of loneliness in Tuareg narratives of travel, dispersion, and return. Transcultural Psychiatry 57: 649–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratcliffe, John, Andrea Wigfield, and Sara Alden. 2021. «A lonely old man»: Empirical investigations of older men and loneliness, and the ramifications for policy and practice. Ageing and Society 41: 794–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivero Jiménez, Borja, David Conde-Caballero, and Lorenzo Mariano Juárez. 2021. Loneliness Among the Elderly in Rural Contexts: A Mixed-Method Study Protocol. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 20: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roos, Vera, and Lelanie Malan. 2012. The role of context and the interpersonal experience of loneliness among older people in a residential care facility. Global Health Action 5: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanley, Mandy, Wendy Moyle, Alison Ballantyne, Katrina Jaworski, Megan Corlis, Deborah Oxlade, Andrew Stoll, and Beverly Young. 2010. «Nowadays you don’t even see your neighbours»: Loneliness in the evereyday lives of older Australians. Health and Social Care in the Community 18: 407–14. [Google Scholar]

- Sayago, Sergio, and Josep Blat. 2009. Older people and ICT: Towards understanding real-life usability and experiences created in everyday interactions with interactive technologies. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics) 5614: 154–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoenbach, Klaus. 2001. Myths of Media and Audiences: Inaugural Lecture as Professor of General Communication Science, University of Amsterdam. European Journal of Communication 16: 361–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snell, Keith David Malcom. 2016. Modern Lonelines in Historical Perspective. In The Correlates of Loneliness. Edited by Ami Rokach. Sharjah: Bentham Science Publishers, pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, Jacob Y., and Rivka Tuval-Mashiach. 2015. The Social Construction of Loneliness: An Integrative Conceptualization. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 28: 210–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strauss, Anselm, and Juliet Corbin. 2002. Bases de La Investigación Cualitativa. In Técnicas y Procedimientos Para Desarrollar La Teoría Fundamentada. Antioquia: Editorial Universidad de Antioquia. [Google Scholar]

- Sum, Shima, R. Mark Mathews, Ian Hughes, and Andrew Campbell. 2008. Internet use and loneliness in older adults. Cyberpsychology and Behavior 11: 208–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tichenor, Phillip J., George A. Donohue, and Clarice N. Olien. 1970. Mass media flow and differential growth in knowledge. Public Opinion Quarterly 34: 159–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valtorta, Nicole, and Barbara Hanratty. 2016. Loneliness, isolation and the health of older adults: Do we need a new research agenda? Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 105: 518–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Victor, Christina, Sasha Scambler, and John Bond. 2009. The Social World of Older People. Understanding Loneliness and Social Isolation in Later Life, 1st ed. Maidenhead: Open University Press/McGraw Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Robert S. 1974. Loneliness: The Experience of Emotional and Social Isolation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, Benjamin, Judy Hoffman, and Jamie Morgenstern. 2019. Predictive Inequity in Object Detection. Available online: http://arxiv.org/abs/1902.11097 (accessed on 20 March 2022).

- Yu, Kexin, Shinyi Wu, and Iris Chi. 2021. Internet Use and Loneliness of Older Adults Over Time: The mediating effect of social contact. The Journals of Gerontology Series: B 76: 541–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name5 | Age | Sex | Marital Status | Household Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emilia | 91 | Female | Widow | Living alone, cared for by her children, dependent. |

| Luz | 71 | Female | Widow | Living alone in her house, her children do not live near |

| Manuel | 84 | Male | Single | Living alone, no close relatives |

| Camilo | 82 | Male | Married | Lives with his wife and one son |

| Manuela | 92 | Female | Widow | Living alone, her children live in the village. |

| Rosana | 68 | Female | Divorcee | Living alone, no children, mobility problems |

| Julia | 77 | Female | Widow | Living alone, no childern |

| Joao | 79 | Male | Married | Living with his wife, no children nearby |

| María | 76 | Female | Married | Living with her husband, they do not leave their house. |

| Sabina | 84 | Female | Widow | Living alone, one of her children lives in the village. |

| Ana | 83 | Female | Widow | Health problems, daughter temporarily in home |

| Luisa | 82 | Female | Couple | Lives with partner, no close relatives |

| Victor | 84 | Male | Couple | Lives with partner, no close relatives |

| Manuel | 70 | Male | Married | Lives with his wife, his children live abroad. |

| Joaquim | 81 | Male | Single | Living alone, no close relatives nearby |

| María | 78 | Female | Married | Living alone, children visit her 2–3 times a week |

| Francisca | 75 | Female | Widow | Living alone, her daughter lives in the village |

| Themes | Categories | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|

| Loneliness | Emic definitions (emotional loneliness vs. social loneliness) | “Lack of companionship” “Lack of social happiness” |

| Feelings of loneliness | “It’s because I get sad. I get that depression thing, which is very bad—and that’s it” | |

| Technology | Perception of “technology” | “My husband switches the telly on and starts surfing channels, searching—but I get bored” |

| Perception of its uses | “Do not give me that WhatsApp thing—because I don’t want it!” | |

| Adoption of new technologies | “I wasn’t very keen before—but it is true that now, with the tablet, they write to me and I can see my daughter” |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rivero Jiménez, B.; Conde-Caballero, D.; Mariano Juárez, L. Technological Utopias: Loneliness and Rural Contexts in Western Iberia. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050191

Rivero Jiménez B, Conde-Caballero D, Mariano Juárez L. Technological Utopias: Loneliness and Rural Contexts in Western Iberia. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(5):191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050191

Chicago/Turabian StyleRivero Jiménez, Borja, David Conde-Caballero, and Lorenzo Mariano Juárez. 2022. "Technological Utopias: Loneliness and Rural Contexts in Western Iberia" Social Sciences 11, no. 5: 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050191

APA StyleRivero Jiménez, B., Conde-Caballero, D., & Mariano Juárez, L. (2022). Technological Utopias: Loneliness and Rural Contexts in Western Iberia. Social Sciences, 11(5), 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11050191