Life Course and Emerging Adulthood: Protestant Women’s Views on Intimate Partner Violence and Divorce

Abstract

:1. Literature Review

1.1. Biblical Inerrancy and Religiosity in Emerging Adulthood

1.2. Religiosity and Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) in Emerging Adulthood

1.3. Life Course Theory

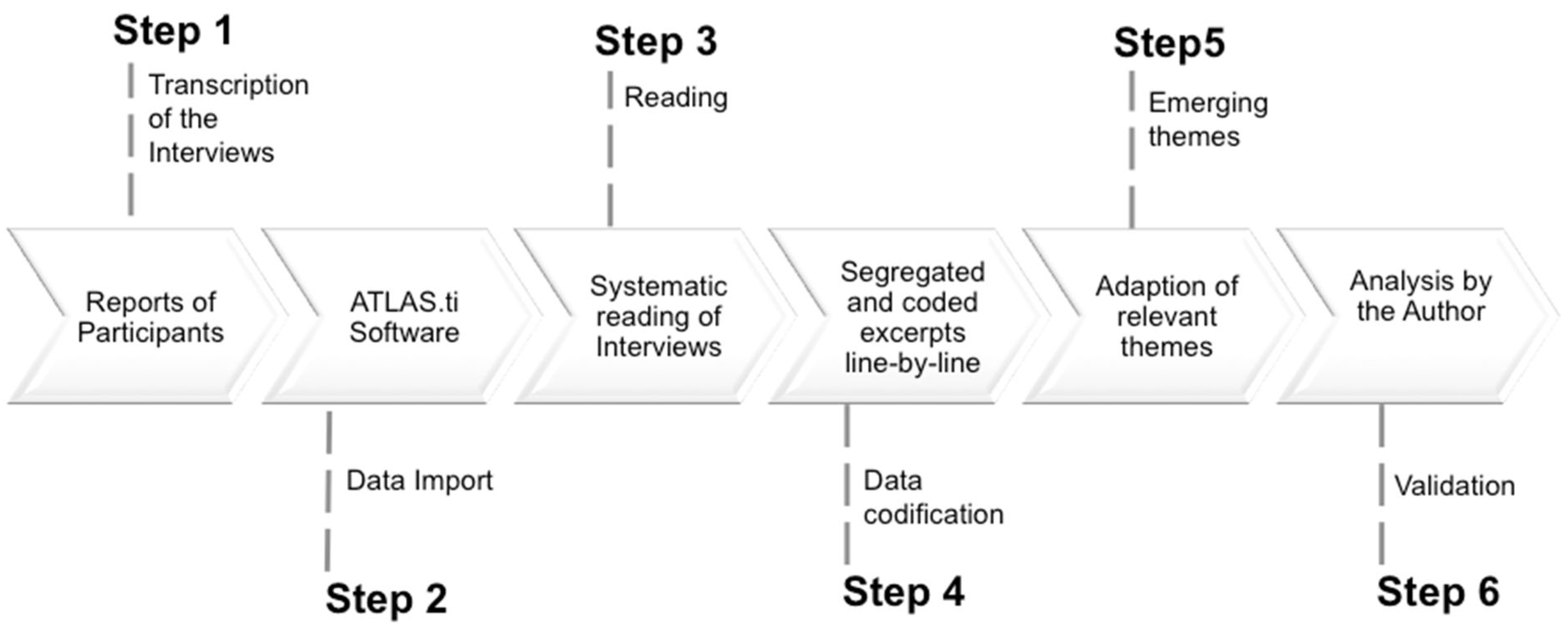

2. Methods

3. Results

- (1).

- How has Protestant women’s religious participation changed since entering emerging adulthood?

“I still kind of identified as being Christian…I just didn’t participate in it anymore. When I first got here [to college], I went to church some and then, um, I don’t know. I didn’t really like the church, it wasn’t really my thing…I would rather just go and hike up a mountain and just sit there and contemplate my existence.”(Sarah)

“I believe there is a God, but I question the denominations…like there was a church that I went to here [in college] and I just did not like it at all. I felt like every time I went to church, I would go out feeling like an awful, horrible person and I was like, I am not. I am a good person…everyone sins and I feel like there are so many hypocritical Christians…I just think its one of those things where like I have questions that aren’t being answered and just like the experiences I have been through… I could easily get back into it, but I just would rather not.”(Adriana)

“They had polarizing views that I did not agree with...they had people [religious speakers] come and talk to us about saving ourselves for marriage…and one thing that I heard people say a lot was “it’s the devil”… like they didn’t do well on their test because the devil made them watch Netflix, so in that talk she [the religious speaker] said: ‘The devil gets in your lives in and out of marriage. Outside of marriage, the devil wants you to have sex, but in marriage, the devil does everything to keep you from having sex.’ I was like, ‘that doesn’t sound right, honey!’” (She laughs)(Tori)

“I am just more involved with the church and I feel like I just know God more because of the years. I am a life group leader and lead on Sunday mornings. I think it’s easier to do because I am living on my own and I don’t have the control of my parents here.”(Natalie)

- (2).

- Do Protestant emerging adult women believe in Biblical inerrancy?

“See this is where it gets hard, because I am kind of on the fence about it. I don’t know. We are not always meant to know this stuff. I feel like a lot of religion was created as a way of a guideline, a sort of rules, so you wouldn’t just have chaos, so…I am not really sure. I don’t know. It could be. I will go with no [the Bible is not the inspired word of God].”(Sarah)

- (3).

- Will Protestant emerging adult women approve of divorce for women experiencing intimate partner violence?

“I would say that the majority of Baptists would say you shouldn’t get divorced. Ya know like in sickness and in health, for richer or poorer, until death do us part. It’s a vow, you know, and I don’t think they think it should be broken, but I personally believe, for instance, that if someone committed adultery… I mean like not only let’s say the wife cheated on the husband, but like, I mean, it’s affecting the family in a bad way… the husband is probably, potentially is never going to get over that and it affects other aspects of their marriage. So something like that, I would think if it ruined the marriage, because someone committed adultery then that’s a good reason to get divorce.”(Ana)

“I would say if a woman or male was getting abused by their partner, that the Baptist people would say they should get a divorce. My dad is a marriage counselor and so, I’ve heard a lot of stories…my dad is an epitome. He lives and breathes the Bible and I see it every day. And um, every little decision and aspect, he relates to the Bible. I remember he mentioned one time that this lady was getting abused and like, he mentioned he thought that they should get a divorce and he wouldn’t have said that if he didn’t think it was a good reason biblically. So I use him for a lot of reference a lot. But yeah, I think that 99% of Baptists would say, ‘s/he should get out, because he could kill her.’ It can go too far one time and then they would be at fault for telling her to stay if she wanted to leave, they would kind of be to blame for that.”(Ana)

“If the marriage becomes abusive, is harmful to any of the spouses, and if it seems like they have literally tried everything to make it work and it’s not working, then it should end.”(Susan)

“Well the only Biblical reason to end marriage is adultery. Now, that is the exception that God has given, but that doesn’t mean that just because adultery happens, he wants you to get a divorce. Like I said, I think marriage is a once in a lifetime thing and I think no matter what happens, you should do whatever it takes to salvage that relationship even if that means being separated for awhile, so not living together. The only time that I think to get a divorce is if you tried everything and it’s still not getting better, is in abusive relationship, but that’s still even knowing that, you know, whoever is abusive is still trying to work it through with them, but if they absolutely cannot, there is no changing, then I believe you should get a divorce and especially if you have children…but I am going to put more weight on the physically abusive rather than the emotionally abusive.”(Ashley)

“I have seen lots of testimonies of couples that have gone through that and the Lord was able to restore those, and so I feel like there is still restoration possible with like those really tough situations and so, I think, I don’t know. I am just not a big fan of divorce at all. I think it’s just caused a lot of destruction.”(Natalie)

“I would say probably that’s okay. I don’t really know. This is so hard without actually having an opinion about this. I would say yeah, like in most of those situations, I feel like that’s a kind of a good reason to get yourself out of that because then it becomes really unsafe…and so I would say if there was a situation where there was physical abuse, then…yes. Like, emotional abuse, though, not so much. I feel like that is something you can work through.”(Natalie)

“I don’t know, I think… if you want your marriage to last, you need to work for it. If you both put enough effort, it should last. I don’t’ think its fair to just get tired of a person… you know if you’ve been married 25 years and then you get tired of them and cheat on them, I don’t think that’s fair. I think you already owe that person so much more, and you owe them an effort for it to work. I don’t think cheating is right at all.”(Katie)

“Abuse. If you are getting physically abused, verbally abused. Um I think also if that person, if they are not even providing anything for you and helping with the children. Cheating is also another reason.”(Katie)

“Um, no. Because I think it becomes empty and unfulfilling based on society’s—on things going on in the world and that if you go back to the basics of your marriage, you find where it started and you fall back in love. I have witnessed it with my parents the last three years—it’s, I mean, my dad took on… he went from a firefighter to a police officer, and I think the outside influence affected him and pulled him away from his marriage and that’s where the problems started…I think if he were to come back and really work on their marriage, like he would realize where it started and why he fell in love with her in the first place, and I mean that is why my parents are still married. She refuses to sign the divorce papers, because she said ‘til death do us part’ and so like that is what I have definitely grown up with…that when you say “I do” that it is forever, divorce isn’t an option…I mean work is placed so high and the outside influence of the demands of the job affects the marriage and because it becomes so common, it’s like well we aren’t happy and we haven’t been happy for a whole month, so lets just get divorced… that being said, a marriage that was started in the right ways, not I met you, we had a one night stand, I got pregnant so we got married! (laughs)(Joanna)

“That depends, I think. Um, on the kids. Well, I don’t know. See my parents were like… it worked, but it wasn’t happy, you know? So that’s kind of what I was used to, I don’t know. Yeah, I don’t know… I don’t know how much harm it did having them together and not happy as opposed to them getting a divorce and… I mean, they are both pretty happy right now [divorced after being married for 22 years], um, I think it was harder for my brother. He had to live with my mom another two years, but now he is out of the house. Um, but I don’t know… that’s a hard question. Yeah, I mean, yeah I guess it was good that they were together for that long, but also no, because they weren’t happy and it was kind of hard on all of us because they would argue and stuff…Yeah, I don’t know if there is a right answer for me.(Tori)

4. Discussion and Conclusions

5. Limitations

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | “I say to you, whoever divorces his wife (unless the marriage is unlawful) and marries another commits adultery” (Matthew 19: 9 from World Bible Publishing St 1987, p. 1040); “He said to them, ‘Whoever divorces his wife and marries another commits adultery against her, and if she divorces her husband and marries another, she commits adultery’” (Mark 10: 11–12 from World Bible Publishing St 1987, p. 1079). |

| 2 | “unless the marriage is unlawful” (Matthew 19: 9 from World Bible Publishing St 1987, p. 1040) |

| 3 | “If the unbeliever separates, however, let him separate. The brother or sister is not bound in such cases” (1 Corinthians 7: 15 from World Bible Publishing St 1987, p. 1237). |

| 4 | (1) life-span development (significant developmental changes take place after 18 years old), (2) human agency (an individual’s choices directly affect their life direction), (3) time and place (the socio-historical context impacts an individual’s worldview and experiences), (4) timing (the impact a series of events and transitions is dependent on when they occur), and (5) linked lives (an individual’s experiences are interdependent on their social relationships). |

References

- Alvarez-Lizotte, Pamela, Sophie M. Bisson, Geneviève Lessard, Annie Dumont, Chantal Bourassa, and Valèrie Roy. 2020. Young Adults’ Viewpoints Concerning Helpful Factors When Living in an Intimate Partner Violence Context. Children and Youth Services Review 119: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammerman, Nancy Tatom. 1987. Bible Believers: Fundamentalists in the Modern World. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey J. 1997. Young People’s Conceptions of the Transition to Adulthood. Youth & Society 29: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2000. Emerging Adulthood: A Theory of Development from the Late Teens Through the Twenties. American Psychologist 55: 469–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2007. Emerging Adulthood: What Is It, and What Is It Good For? Society for Research in Child Development 1: 68–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen. 2015. Introduction to the Special Section: Reflections on Expanding the Cultural Scope of Adolescent and Emerging Adult Research. Journal of Adolescent Research 30: 655–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Arnett, Jeffrey Jensen, and Lene Arnett Jensen. 2002. A Congregation of One: Individualized Religious Beliefs Among Emerging Adults. Journal of Adolescent Research 17: 451–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ATLAS.ti. 2002–2013. Scientific Software Development. Version 1.0.27 (104). Berlin: GmbH. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoszuk, Karin, and James E. Deal. 2016. Personality, Identity Styles, and Fundamentalism During Emerging Adulthood. An International Journal of Theory and Research 16: 142–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berkel, LaVerne A., Beverly J. Vandiver, and Angela D. Bahner. 2004. Gender Role Attitudes, Religion, and Spirituality as Predictors of Domestic Violence Attitudes In White College Students. Journal of College Student Development 45: 119–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, Michele C., Kathleen C. Basile, Matthew J. Breiding, Sharon G. Smith, Mikel L. Walters, Melissa T. Merrick, Jieru Chen, and Mark. R. Stevens. 2011. The National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey (NISVS): 2010 Summary Report. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Carbone-Lopez, Kristin, Callie Marie Rennison, and Ross Macmillan. 2012. The Transcendence of Violence Across Relationships: New Methods for Understanding Men’s and Women’s Experiences of Intimate Partner Violence Across the Life Course. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 28: 319–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, Mark. 2011. American Religion: Contemporary Trends. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper-White, Pamela. 2011. Intimate Violence Against Women: Trajectories for Pastoral Care in a New Millennium. Pastoral Psychology 60: 809–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Côté, James E. 2000. Arrested Adulthood: The Changing Nature of Maturity and Identity. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Côté, James E. 2006. Emerging Adulthood as an Institutionalized Moratorium: Risks and Benefits to Identity Formation. In Emerging Adults in America: Coming of Age in the 21st Century. Edited by Jeffrey Jensen Arnett and Jennifer Lynn Tanner. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Denton, Melinda Lundquist. 2012. Family Structure, Family Disruption, and Profiles of Adolescent Religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 51: 42–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Desmond, Scott A., Kristopher H. Morgan, and George Kikuchi. 2010. Religious Development: How (and Why) Does Religiosity Change From Adolescence to Young Adulthood? Sociological Perspectives 53: 247–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumont, Annie, and Geneviève Lessard. 2020. Young Adults Exposed to Intimate Partner Violence in Childhood: The Qualitative Meanings of This Experience. Journal of Family Violence 35: 781–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagan, Kevin. 2016. The American Freshman: Fifty-Year Trends, 1966–2015. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA. [Google Scholar]

- Elder, Glen H. 1998. The Life Course as Developmental Theory. Child Development 69: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elder, Glen H., Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson, and Robert Crosnoe. 2003. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In Handbook of the Life Course. Edited by Jeylan T. Mortimer and Michael J. Shanahan. Boston: Springer, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, Christopher G., and Kristen L. Anderson. 2001. Religious Involvement and Domestic Violence Among US Couples. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 40: 269–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellison, Christopher G., John P. Bartkowski, and Kristin L. Anderson. 1999. Are There Religious Variations in Domestic Violence? Journal of Family Issues 20: 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, Robert M. 2001. Contemporary Field Research: Perspectives and Formulations. Long Grove: Waveland Press, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson, Erik H. 1963. Childhood and Society, 2nd ed. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Etherington, Nicole A., and Linda L. Baker. 2016. The Link Between Boys’ Victimization and Adult Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence: Opportunities for Prevention Across the Life Course. London: Centre for Research & Education on Violence. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald, Scott T., and Jennifer Glass. 2008. Can Early Family Formation Explain the Lower Educational Attainment of U.S. Conservative Protestants? Sociological Spectrum: Mid-South Sociological Association 28: 556–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallagher, Sally K. 2003. Evangelical Identity and Gendered Family Life. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. 2022. Religion. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/1690/religion.aspx (accessed on 31 October 2021).

- Gillett, Shirley. 1996. No Church to Call Home. In Women, Abuse, and the Bible: How Scripture Can Be Used to Hurt or Heal. Edited by Catherine Clark Kroeger and James R. Beck. Grand Rapids: Baker Books, pp. 106–14. [Google Scholar]

- Glass, Jennifer, and Jerry Jacobs. 2005. Childhood Religious Conservatism and Adult Attainment Among Black and White Women. Social Forces 84: 551–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haaken, Janice, Holly Fussell, and Eric Mankowski. 2007. Bringing the Church to its Knees: Evangelical Christianity, Feminism, and Domestic Violence Discourse. Psychotherapy and Politics International 5: 103–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haney, Alison M., and David Rollock. 2020. A Matter of Faith: The Role of Religion, Doubt, and Personality in Emerging Adult Mental Health. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 12: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higginbotham, Brian J., Scott A. Ketring, Jeff Hibbert, David W. Wright, and Anthony Guarino. 2007. Relationship Religiosity, Adult Attachment Styles, and Courtship Violence Experienced by Females. Journal of Family Violence 22: 55–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoge, Dean R., Benton Johnson, and Donald A. Luidens. 1993. Determinants of Church Involvement of Young Adults Who Grew Up in Presbyterian Churches. Journal of the Scientific Study of Religion 32: 242–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Melissa S., Meredith G. F. Worthen, Susan F. Sharp, and David A. McLeod. 2018. Life As She Knows It: The Effects of Adverse Childhood Experiences on Intimate Partner Violence Among Women Prisoners. Child Abuse & Neglect 85: 68–79. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman-Parks, Angela M., Alfred DeMaris, Peggy C. Giordano, Wendy D. Manning, and Monica A. Longmore. 2018. Intimate Partner Violence Perpetration From Adolescence to Young Adulthood: Trajectories and The Role of Familial Factors. Journal of Family Violence 33: 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaukinen, Catherine, Angela R. Gover, and Jennifer L. Hartman. 2012. College Women’s Experiences of Dating Violence in Casual and Exclusive Relationships. American Journal of Criminal Justice 37: 146–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Angie C., Deborah Bybee, Heather L. McCauley, and Kristen A. Prock. 2018. Young Women’s Intimate Partner Violence Victimization Patterns Across Multiple Relationships. Psychology of Women Quarterly 42: 430–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Angie C., Elizabeth Meier, and Kristen A. Prock. 2021. A Qualitative Study of Young Women’s Abusive First Relationships: What Factors Shape Their Process of Disclosure? Journal of Family Violence 36: 849–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, Jerome R., and Ignacio Luis Ramirez. 2010. Religiosity, Christian Fundamentalism, and Intimate Partner Violence Among U.S. College Students. Review of Religious Research 51: 402–10. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig, Laura B. 2015. Change and Stability in Religiousness and Spirituality in Emerging Adulthood. The Journal of Genetic Psychology 176: 369–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koenig, Laura B., Matt McGue, and William G. Iacono. 2008. Stability and Change in Religiousness During Emerging Adulthood. Developmental Psychology 44: 532–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krigel, Karni, and Orly Benjamin. 2020. Women Working in the Shadow of Violence: Studying the Temporality of Work and Violence Embeddedness (WAVE). Women’s Studies International Forum 102433: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Ferle, Carrie, and Sidharth Muralidharan. 2019. The Role of Religiosity in Motivating Christian Bystanders to Intervene. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 58: 874–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacCharles, Jeffrey D., and E. Nicole Melton. 2021. Charting Their Own Path: Using Life Course Theory to Explore the Careers of Gay Men Working in Sport. Journal of Sport Management 35: 407–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macmillan, Ross, and Rosemary Gartner. 1999. When She Brings Home the Bacon: Labor-Force Participation and the Risk of Spousal Violence Against Women. Journal of Marriage and the Family 61: 947–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Wendy D., Monica A. Longmore, and Peggy C. Giordano. 2018. Cohabitation and Intimate Partner Violence During Emerging Adulthood: High Constraints and Low Commitment. Journal of Family Issues 39: 1030–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Laura M., and Reeve Vanneman. 2003. Context Matters: Effects of the Proportion of Fundamentalists on Gender Attitudes. Social Forces 82: 115–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Paat, Yok-Fong, and Christine Markham. 2019. The Roles of Family Factors and Relationship Dynamics on Dating Violence Victimization and Perpetration Among College Men and Women in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 81–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pascarella, Ernest T., and Patrick T. Terenzini. 1991. How College Affects Students: Findings and Insights from Twenty Years of Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, Lisa, and Melinda Lundquist Denton. 2011. A Faith of Their Own: Stability and Change in the Religiosity of America’ s Adolescents. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Peek, Charles W., George D. Lowe, and L. Susan Williams. 1991. Gender and God’s Word: Another Look at Religious Fundamentalism and Sexism. Social Forces 69: 1205–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perales, Francisco, and Gary Bouma. 2019. Religion, Religiosity and Patriarchal Gender Beliefs: Understanding the Australian experience. Journal of Sociology 55: 323–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Perry, William Graves. 1999. Forms of Ethical and Intellectual Development in the College Years: A Scheme. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Pew Research Center. 2010. Religion Among the Millenials. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2010/02/millennials-report.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Pew Research Center. 2012. The Global Religious Landscape. Available online: http://assets.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/11/2014/01/global-religion-full.pdf (accessed on 30 October 2021).

- Policastro, Christina, and Leah E. Daigle. 2019. A Gendered Analysis of the Effects of Social Ties and Risky Behavior on Intimate Partner Violence Victimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 34: 1657–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renzetti, Claire M., C. Nathan DeWall, Amy Messer, and Richard Pond. 2017. By the Grace of God: Religiosity, Religious Self-regulation, and Perpetration of Intimate Partner Violence. Journal of Family Issues 38: 1974–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizo, Cynthia. 2016. Intimate Partner Violence Related Stress and the Coping Experiences of Survivors: There’s Only So Much a Person Can Handle. Journal of Family Violence 31: 581–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberto, Karen A., and Brandy Renee McCann. 2021. Violence and Abuse in Rural Older Women’s Lives: A Life Course Perspective. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36: 2206–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodenhizer, Kara Anne E., Katie M. Edwards, Emily E. Camp, and Sharon B. Murphy. 2021. It’s HERstory: Unhealthy Relationships in Adolescence and Subsequent Social and Emotional Development in College Women. Violence Against Women 27: 1337–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saltzman, Linda E., Janet L. Fanslow, Pamela M. McMahon, and Gene A. Shelley. 1999. Intimate Partner Violence Surveillance: Uniform Definitions and Recommended Data Elements, Version 1.0. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore, Christopher. 2017. The Emerging Adulthood Gap: Integrating Emerging Adulthood into Life Course Criminology. International Social Science Review 93: 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Sharp, Shane. 2009. Escaping Symbolic Entrapment, Maintaining Social Identities. Social Problems 56: 267–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, Rui, André Coelho, Nuno Sousa, and Patrícia Quesado. 2021. Family Business Management: A Case Study in the Portuguese Footwear Industry. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 7: 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonič, Barbara. 2021. The Power of Women’s Faith in Coping with Intimate Partner Violence: Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Religion and Health 60: 4278–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Christian. 1998. American Evangelicalism: Embattled and Thriving. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Christian. 2021. Religious Identity and Influence Survey, 1996. The Association of Religion Data Archives (ARDA). Available online: https://www.thearda.com/Archive/Files/Descriptions/RIIS.asp (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Smith, Christian, and Patricia Snell. 2009. Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan A., Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin. 2009. Interpreative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Spilman, Sarah K., Tricia K. Neppl, M. Brent Donnellan, Thomas J. Schofield, and Rand D. Conger. 2013. Incorporating Religiosity into a Developmental Model of Positive Family Functioning Across Generations. Developmental Psychology 49: 762–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Spišákova, Dominika, and Beáta Ráczová. 2020. Emerging Adulthood Features: An Overview of the Research in Approaches and Perspectives in Goals Area. Individual and Society 23: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station: StataCorp LP. [Google Scholar]

- Tenkorang, Eric Y., and Adobea Y. Owusu. 2018. A Life Course Understanding of Domestic and Intimate Partner Violence in Ghana. Child Abuse and Neglect 79: 384–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uecker, Jeremy E., Mark D. Regnerus, and Margaret L. Vaaler. 2007. Losing My Religion: The Social Sources of Religious Decline in Early Adulthood. Social Forces 85: 1667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, Debra, Mieke Beth Thomeer, Kristi Williams, Patricia A. Thomas, and Hui Liu. 2016. Childhood Adversity and Men’s Relationships in Adulthood: Life Course Processes and Racial Disadvantage. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences 71: 902–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Walker, Anthony B. 2019. An Exploration of Family Factors Related to Emerging Adults’ Religious Self-Identification. Religions 10: 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Mei-Chuan, Sharon G. Horne, Heidi M. Levitt, and Lisa M. Klesges. 2009. Christian Women in IPV Relationships: An Exploratory Study of Religious Factors. Journal of Psychology and Christianity 28: 224–35. [Google Scholar]

- Westenberg, Leonie. 2017. When She Calls for Help: Domestic Violence in Christian Families. Social Sciences 6: 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wilcox, Bradford. 2004. Soft Patriarchs, New Men: How Christianity Shapes Fathers and Husbands. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willits, Fern K., and Donald M. Crider. 1989. Church Attendance and Traditional Religious Beliefs in Adolescence and Young Adulthood: A Panel Study. Review of Religious Research 31: 68–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bible Publishing St. 1987. The New American Bible. Pittsburgh: World Catholic Press. [Google Scholar]

| Participant | Pseudo-Name | Age | Relationship Status | Parents’ Marital Status | Religion | Religious Participation | Belief in Biblical Inerrancy * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ana | 21 | Single | Married | Baptist | Decreased | C |

| 2 | Susan | 21 | Single | Widowed | Methodist | Increased | B |

| 3 | - | 20 | Single | Married | Methodist | Decreased | B |

| 4 | - | 20 | Single | Married | United Methodist | Decreased | B |

| 5 | Katie | 19 | Single | Married | Baptist | Increased | B |

| 6 | Adriana | 20 | Single | Married | Episcopalian | Decreased | C |

| 7 | Ashley | 21 | Single | Married | NDC | Increased | B |

| 8 | - | 20 | Relationship | Divorced | NDC | Increased | B |

| 9 | Mary | 22 | Relationship | Married | Baptist | Increased | B |

| 10 | Joanna | 21 | Single | Separated | Lutheran | Decreased | B |

| 11 | Krystal | 19 | Relationship | Married | Episcopalian | Decreased | C |

| 12 | Chanel | 22 | Relationship | Married | Methodist | About the Same | B |

| 13 | Jenna | 22 | Single | Widowed | NDC | Decreased | A |

| 14 | Sarah | 22 | Single | Married | Methodist | Decreased | D |

| 15 | Julia | 20 | Relationship | Married | Lutheran | Decreased | B |

| 16 | - | 19 | Single | Divorced | NDC | Decreased | C |

| 17 | Emily | 20 | Single | Married | NDC | Decreased | B |

| 18 | Natalie | 19 | Single | Married | NDC | Increased | B |

| 19 | Tori | 20 | Single | Divorced | Presbyterian | Decreased | C |

| 20 | - | 21 | Single | Married | Baptist | Decreased | A |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ochoa, M.K. Life Course and Emerging Adulthood: Protestant Women’s Views on Intimate Partner Violence and Divorce. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040169

Ochoa MK. Life Course and Emerging Adulthood: Protestant Women’s Views on Intimate Partner Violence and Divorce. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(4):169. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040169

Chicago/Turabian StyleOchoa, Melissa K. 2022. "Life Course and Emerging Adulthood: Protestant Women’s Views on Intimate Partner Violence and Divorce" Social Sciences 11, no. 4: 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040169

APA StyleOchoa, M. K. (2022). Life Course and Emerging Adulthood: Protestant Women’s Views on Intimate Partner Violence and Divorce. Social Sciences, 11(4), 169. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11040169