Abstract

The term political extremism is commonly used to refer to political attitudes considered to be outside the ideological mainstream. This study leverages computational content analysis of big data to longitudinally examine (1970–2019) the prevalence of terms denoting far-right and far-left political extremism in more than 30 million written news and opinion articles from 54 news media outlets popular in the United States and the United Kingdom. We find that the usage of terms denoting right and left political extremism has been increasing across news media outlets in both countries. This trend is particularly stark for far-right-denoting terms, which have been growing in prevalence since at least 2008. Most U.S. and U.K. news media outlets tend to use far-right-denoting terms substantially more often than they use far-left-denoting terms. The rising prevalence in news media of terms denoting political extremism is strongly correlated with similar growing usage of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse.

1. Introduction

Recent years have seen a growth of electoral support for populist right-wing political parties and candidates in North America (Jardina 2019; Mutz 2018; Sides et al. 2018) and Europe (Betz 1998; Norris 2005; Norris and Inglehart 2019) and also radical left-wing parties, especially in Europe, which have doubled their level of support since the 1980s (Krause 2020). Thus, it would be conceivable that news media have reflected in their content the apparent growth of political extremism in the wider society.

In some limited cases, the role of partisan media in driving political extremism has been suggested because new partisan media sources come bundled with cable laid in some homes but not others, creating quasi-control and treatment groups (DellaVigna and Kaplan 2006). Some authors have also shown partial evidence that exposure to ideological homogeneity in news media can drive attitude extremism (Warner 2010). Yet, the full role of news media in driving and/or responding to political extremism remains unclear.

The rise of political candidates and parties outside of the ideological mainstream has occurred in tandem with largely exogenous changes in the media landscape that stem from technological change and the lifting of regulations such as the Fairness Doctrine (Pickard 2018). The link between news media and right-wing extremism has been comparatively explored at greater length than the link between news media and religious extremism or between news media and left-wing political extremism (Alvares and Dahlgren 2016; Müller and Schulz 2021). The role of financial incentives in the manufacturing of political extremism by news media has been suggested before (Bandyopadhyay et al. 2015). Nevertheless, the causal impact of an increasingly decentralized and deregulated mass media—from talk radio to cable TV to the new pay-per-click online revenue model—on political extremism is underdetermined (Klein 2020).

Numerous studies show that those who consume partisan media display greater issue sorting, extremism and negative partisanship than those who do not (Bruine de Bruin et al. 2020; Levy 2021; Martin and Yurukoglu 2017). Ideological extremism has been associated with a preference for news media consumption through social media that leverages social curation via ideological peers to avoid dissonant information from mainstream media sources (Möller et al. 2020). In fact, a common feature among holders of political extremist beliefs is their negative perception of mainstream news media (Baugut and Neumann 2019; Fawzi 2019).

It is well established that news media can play an important agenda-setting role in public opinion (McCombs 2005). The increasing prominence in news media of terrorism, crime or prejudice has been shown to precede increased public concern about terrorism, crime or prejudice, irrespective of the actual prevalence of terror incidents, crime rates or prejudicial attitudes in society (Callanan 2012; Lowry et al. 2003; Rozado et al. 2021; Smith et al. 2019). The agenda-setting literature also finds that trends in prestigious news outlets seem to precede similar tendencies in less prominent media organizations, as most journalists strive to emulate trends in prestige media (McCombs 2005).

Previous work has reported how the stigmatization of political parties by news media reduces their electoral support (van Spanje and Azrout 2019). Thus, news media elites could be tempted to undermine political attitudes they dislike by portraying them in terms that suggest extreme political beliefs for agenda-setting purposes (McCombs 2005). Indeed, some members of the public, according to political or religious orientation, have been shown to favor controversial journalistic practices such as politically biased reporting as means to combat political extremism (Baugut and Scherr 2021).

Methodologically, we address a glaring gap in the survey- and election-data-based literature on political extremism by introducing a big data measure of discursive prevalence in news media of terms suggestive of political extremism. Computational content analysis of news outlets' content can be useful to analyze the dynamics of patterns embedded in journalistic discourse (Caliskan et al. 2017; Kozlowski et al. 2019; Rozado and al-Gharbi 2021). Plotting word frequencies from a longitudinal corpus of news outlets’ written content tracks the time course of historical phenomena and can illuminate the cultural context in which such texts were produced (Rozado 2020; Rozado et al. 2021).

The observational methodology used in this work is limiting since it does not allow us to make causal inferences about what is driving the observed media trends over time. That is, we cannot elucidate whether news media is exaggerating the prevalence of political extremism by increasingly characterizing political factions they dislike as extreme or if the media is simply responding to actual rising political extremism in society. Thus, our aim is mostly descriptive in our attempt at longitudinally documenting the frequency of terms denoting far-right and far-left political extremism across a large and representative set of written news and opinion articles from news media outlets popular in the United States and the United Kingdom.

2. Materials and Methods

The textual content of news and opinion articles from the 54 outlets analyzed, listed in Figure S1 and Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials (SM), is available in the outlets’ online domains and/or public cache repositories such as Google cache, The Internet Wayback Machine (Notess 2002) or Common Crawl (Mehmood et al. 2017). The textual content included in our analysis is circumscribed to the articles’ headline and main text. This work has not analyzed video or audio content from news media organizations, except when an outlet explicitly provides a transcript of such content in article form. Targeted articles’ URLs were located using a variety of methods such as online indexes, pagination, search engine searches by date of publication tag or crawling/parsing of public online domains or public cache repositories. The targeted textual content was located in HTML raw data using outlet-specific XPath expressions. Tokens were lowercased prior to estimating frequency counts.

To prevent outlets with sparse text content for a year from distorting average yearly frequency counts across outlets, we only include outlet frequency counts from years for which the outlet has at least 1 million words of articles’ textual content available. This threshold was chosen to maximize inclusion in our analysis of outlets with low article volume per year, such as Reason, AlterNet or The American Spectator, while simultaneously maintaining a large enough sample size of words to obtain accurate frequency counts per outlet/year.

Yearly frequency usage of a target word or n-gram in an outlet was estimated by dividing the number of occurrences of the target word/n-gram in all articles within a given year by the total number of all words in all articles of that year. This method of estimating frequency accounts for the variable volume of total article output over time.

The temporal coverage of article availability in different online news outlets is not uniform. For most media organizations, substantial news article availability in online domains or Internet cache repositories becomes sparse in earlier years. This is not the case for a few news outlets, such as The New York Times or The Washington Post, where online availability of news articles goes back as far as the 1970s. Still, frequency data of news media word usage is constrained in its representativeness since most news outlets do not have online availability of news article content in their online domains prior to the year 2000. Figures S3 and S4 in the Supplementary Materials illustrate the time ranges of article data analyzed based on news outlets’ online articles availability and the number of words and articles per outlet/year fulfilling our minimum total yearly word count inclusion criteria.

In a small percentage of articles, outlet-specific XPath expressions failed to properly capture the content of the article due to the heterogeneity of HTML elements and CSS styling combinations with which the articles’ text content is arranged in outlets’ online domains. As a result, the total and target word count metrics for a small subset of articles might not be precise.

Most of the incorrect frequency counts were only minor deviations from the actual counts, such as, for instance, counting a target word in an article footnote or sidebar that the XPath expression mistakenly included as the content of the article’s main text. Some additional outlet-specific inaccuracies that we could identify occurred in The Hill and Newsmax news outlets, where XPath expressions were suboptimal at precisely capturing articles’ content. For The Hill, in the years 2007–2009, XPath expressions failed to capture the complete text of the article in about 40% of the articles. This does not necessarily result in incorrect frequency counts for that outlet but in a sample of articles’ words that is about 40% smaller than the total population of articles words for those years. In the case of NewsMax, the issue was that for some articles, XPath expressions mistakenly captured the entire text of the article twice. This again does not result in incorrect frequency counts. If a word appears times in an article with a total of words, the same frequency count will still be derived when the script counts the word times in the version of the article with a total of words.

In a data analysis of millions of articles, we cannot manually check the correctness of frequency counts for every single article, and one hundred percent accuracy at capturing articles’ content is elusive due to the small number of difficult-to-detect edge cases, such as noncompliant HTML markup syntax in online domains. Overall, however, our derived frequency metrics appear to be representative of word prevalence in print news media content, as illustrated by Figure 1.

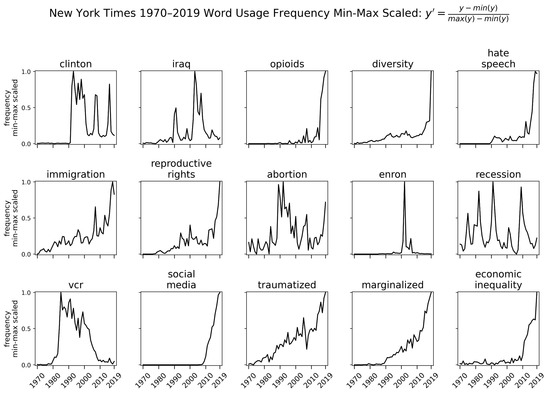

Figure 1.

Min-max scaled yearly frequencies of word usage in New York Times articles.

Figure 1 shows the min-max scaled yearly frequencies of several illustrative words in The New York Times content during the past 50 years. Min-max scaling is a common way to normalize time series. The method rescales the range of the data to a scale between 0 and 1 using the formula shown in Equation (1), where is the original frequency count for a given word, and is its normalized/scaled value. Min-max scaling of frequency counts allows for the comparison of minimum and maximum temporal prevalence across terms in the corpus irrespective of their absolute/relative frequency ranges.

Our set of target terms denoting right and left political extremism was selected by emphasizing symmetry (i.e., far-right/far-left, right-wing/left-wing extremism, etc.) to attempt a fair comparison when documenting the prevalence of terms signifying political extremism in news media content. While our methodology is not perfect, we are not aware of a better or more rigorous methodology for evaluating bespoke words used by each side of the political spectrum to refer to extremism on the opposite side.

We used external human ratings of outlet ideological leanings to classify outlets by their political leanings. For U.S.-based outlets, we used the comprehensive AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (AllSides 2019). For U.K.-based news outlets, we used a majority voting of human ratings from Ad Fontes Media, YouGov and AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (Andrew McGee 2021; YouGov 2021; AllSides 2019); see Supplementary Materials for details.

Bartlett’s test of sphericity confirmed that the frequency-time series of our target far-right- and far-left-denoting terms were highly correlated, thus suggesting the potential of factor analysis to derive latent factors. A Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test confirmed the suitability of the far-right terms time series for factor analysis (KMO = 0.75). The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test for the far-left terms time series was slightly suboptimal (KMO = 0.55). The number of factors to extract was determined using an eigenvalue cutoff of 2 to establish a minimum threshold for how much of the total time series each factor explains. Factor estimation was carried out using varimax rotations. A factor loading cutoff of 0.5 was used to ascribe terms to a factor. Chronbach alphas to determine if the resulting factors appeared coherent were all above 0.82.

3. Results

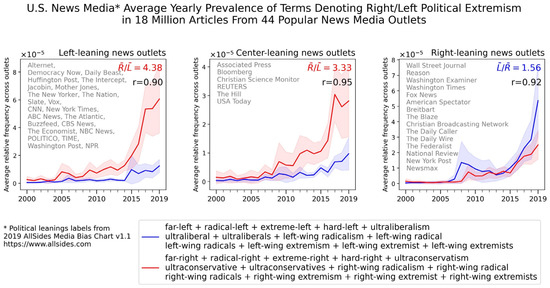

The average yearly prevalence of words denoting left- and right-wing political extremism across 44 U.S. news media outlets’ content arranged by outlets’ ideological leanings according to human ratings from AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (AllSides 2019) is shown in Figure 2. Left-leaning news outlets have tended to use terms that denote far-right political extremism, on average, four times more often than terms that denote far-left political extremism for the time period 2000–2019 (ratio of average far-right to average far-left terms frequency: /). There is an increasing trend in the usage of terms denoting right-wing political extremism in left-leaning news outlets prior to 2015, but the pattern appears to accelerate after that pivotal year, which saw the political emergence of Donald Trump. A similar trend is observable in human-rated center-leaning news outlets, with the average prevalence of far-right-denoting terms being, on average, more than three times higher than the prevalence of far-left political extremism (/). For left- and center-leaning outlets, the / ratio also appears to be increasing over time. Conversely, right-leaning outlets use, on average, terms denoting far-left political extremism only slightly more often than they use terms denoting far-right political extremism ().

Figure 2.

Average yearly prevalence of an aggregate set of terms denoting far-right (red) and far-left (blue) political extremism in 44 popular U.S. news media outlets arranged by outlets’ ideological leanings according to human ratings from AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (AllSides 2019). Shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence interval around the mean. The average prevalence ratio between both time series (/ or ) is color-coded according to which ratio is dominant. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, of the time series is shown on the top right of each subplot.

The usage of both far-right and far-left denoting terms appears to be rising across outlets regardless of their ideological leanings, but the pattern is more pronounced for far-right denoting terms. There is a mild uptick in the usage of terms denoting far-left political extremism in right-leaning outlets coinciding with Barack Obama’s victory in the U.S. presidential election of 2008, though this is much less pronounced than the recent rise in terms denoting far-right political extremism in left-leaning outlets. Another noteworthy feature of these results is that, on average, right-leaning news outlets are about two times more likely to talk about right-wing political extremism than left-leaning news outlets are to talk about left-wing political extremism. Across the political spectrum, the correlation between the time series representing the usage of terms denoting left- and right-wing political extremism terms is high.

A potential confound in Figure 2 is the decreasing availability of news articles’ content in outlets’ online domains for earlier years and the fact that some influential outlets in 2019 did not exist in the early 2000s (see Supplementary Materials for metrics of articles availability per outlet/year). However, replicating the analysis in Figure 2 for the 27 media outlets with continuous news content available since at least 2010 shows the same trends as those in Figure 2 (see Supplementary Materials for details). We also replicated the analysis in Figure 2 with the 10 U.S. outlets in our data set with continuous article content available since the year 2000. The results are very similar to those in Figure 2 for left-leaning and center-leaning news outlets. In contrast, the three right-leaning news outlets (The Wall Street Journal, The New York Post and The Washington Times) fulfilling the inclusion criteria for this analysis showed a higher prevalence of far-right-denoting terms than far-left-denoting terms in recent years’ content (see Supplementary Materials).

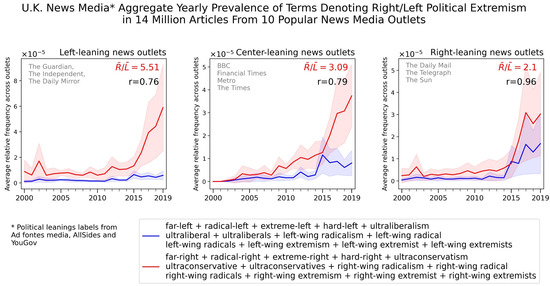

We replicated the analysis above for 10 popular news media outlets based in the United Kingdom. The results are very similar to those from U.S. news outlets (see Figure 3), with rising usage of terms denoting political extremism, a higher overall prevalence of far-right-denoting terms than far-left-denoting terms and even right-leaning news media using far-right-denoting terms more often than they use far-left-denoting terms. Right-leaning news outlets in the U.K. are, on average, five times more likely to use far-right denoting terms than left-leaning news outlets are to use far-left denoting terms. Replicating these analyses for the 6 U.K. news outlets with continuous availability of news content since the mid-2000s generates similar results (see Supplementary Materials).

Figure 3.

Average yearly prevalence of an aggregate set of terms denoting far-right (red) and far-left (blue) political extremism in 10 popular U.K. news media outlets arranged by outlets’ ideological leanings according to human ratings from AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1, Ad Fontes Media and YouGov (AllSides 2019; Andrew McGee 2021; YouGov 2021). Shaded areas indicate the 95% confidence interval around the mean. The average prevalence ratio between both time series (/ or ) is color-coded according to which ratio is dominant. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, between the time series is shown on the top right of each subplot.

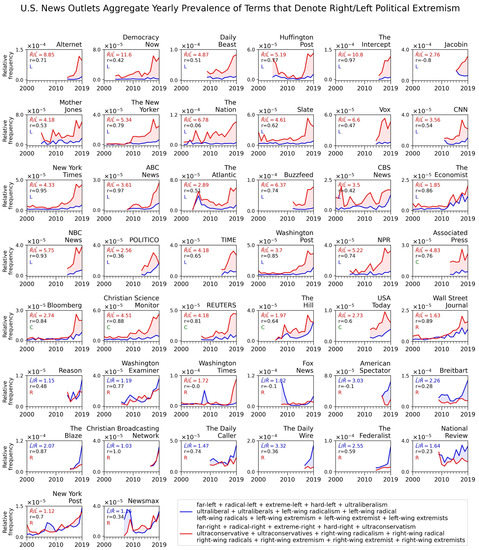

Figure 4 shows the prevalence of far-right- and far-left-denoting terms in all the individual U.S. outlets studied. This disaggregation by source shows that the growing usage of terms denoting political extremism is visible within most outlets, thus confirming the consistency of the trend across media organizations. The trend of left-leaning and center-leaning news outlets using far-right denoting terms substantially more often than far-left denoting terms is likewise apparent. Right-leaning outlets display a more moderate and diverse pattern. Similar to their left-leaning counterparts, some right-leaning outlets such as The Wall Street Journal, The Washington Times or The New York Post tend to use far-right denoting terms more often than they use far-left denoting terms. Other right-leaning news outlets, like Breitbart or National Review, tend to use extreme-left denoting terms more often than extreme-right denoting terms. However, the ratio of the political out-group being characterized as extreme tends to be more moderate in right-leaning than in left-leaning news outlets. Whether this disparity stems from biased news media perceptions or the empirical reality of more far-right than far-left activity is beyond the scope of this analysis. It could also be that right-wing partisan outlets use a wider set of terms to refer to the far-left than vice-versa. However, as there is no clear methodology for compiling a list of comparable bespoke terms, we opted to use a consistent set of pairings that emphasize symmetry between the two sets of terms denoting right and left political extremism.

Figure 4.

Yearly prevalence of an aggregate set of terms denoting far-right (red line) and far-left (blue line) political extremism in popular U.S. news media outlets. The colored area between time series for each outlet is used to highlight the dominant prevalence. Red areas indicate higher average prevalence of far-right denoting terms. Conversely, blue areas indicate higher prevalence of far-left denoting terms. The average prevalence ratio between both time series (/ or ) is also color-coded according to which ratio is dominant. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, between the time series is shown on the top left of each subplot. The political bias from each outlet, according to the AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (AllSides 2019), is indicated with L (left-leaning), C (center-leaning) and R (right-leaning).

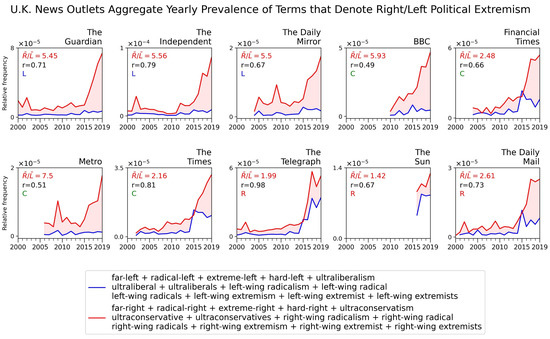

Replicating the analysis above for all the individual outlets in the U.K. generates similar results; see Figure 5. All ten outlets analyzed, including right-leaning sources, use terms denoting far-right political extremism more often than they use terms denoting far-left political extremism.

Figure 5.

Yearly prevalence of an aggregate set of terms denoting far-right (red line) and far-left (blue line) political extremism in popular U.K. news media outlets. The colored area between time series for each outlet is used to highlight the dominant prevalence. Red areas indicate higher prevalence of far-right denoting terms. Conversely, blue areas would indicate higher prevalence of far-left denoting terms. The average prevalence ratio between both time series (/ or ) is also color-coded according to which ratio is dominant. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, between the time series is shown on the top left of each subplot. The political bias from each outlet, according to a majority voting from media bias rating sources including AllSides Media Bias Chart 2019 v1.1 (AllSides 2019), YouGov (YouGov 2021) and Ad Fontes Media (Andrew McGee 2021), is indicated with L (left-leaning), C (center-leaning) and R (right-leaning).

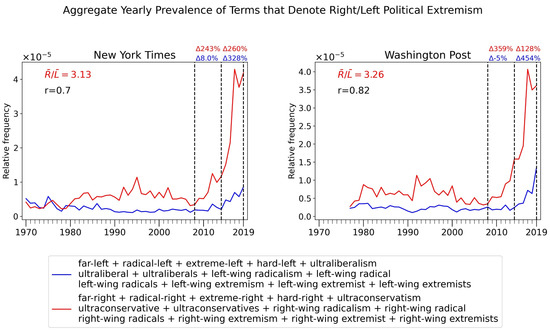

Figure 2 and Figure 3 only display the prevalence patterns of political extremism denoting terms in news media content for the time interval 2000–2019. We next examine the prevalence of such terms for a longer time frame. Only two influential news outlets in our data set have substantial news articles content available online all the way back to the 1970s: The New York Times and The Washington Post. Thus, we replicate the analysis in Figure 2 above for just those outlets for the time range encompassing 1970–2019; see Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Yearly prevalence of an aggregate set of terms denoting far-right (red) and far-left (blue) political extremism in two prestigious news media outlets: The New York Times and The Washington Post. The average dominant prevalence ratio between both time series is displayed as /. The Pearson correlation coefficient, r, between the time series is shown on the top left of each subplot. The years 2008, 2014 and 2019 are highlighted with vertical dashed lines. The percentage growth of target terms between 2008 and 2014 and between 2014 and 2019 for each time series is indicated with color-coded deltas (Δ).

In the 1970s, The New York Times used terms denoting far-right and far-left political extremism at a comparable rate. Since the 1980s, however, both in The New York Times and in The Washington Post, the prevalence of right-wing-extremism-denoting terms has been, on average, more than three times higher than the prevalence of terms denoting left-wing extremism. Usage of terms denoting right-wing political extremism has been relatively stable from the 1980s until around 2010, with a mild prevalence peak in the mid-1990s. Usage of terms denoting far-left political extremism has been relatively stable since the 1980s, but the usage of such terms started to grow in 2015. Figure 6 highlights with vertical dashed lines three relevant years: 2008, when Barack Obama won for the first time the U.S. presidential election; 2014, the year prior to the 2015 entrance of Donald Trump into the U.S. political scene and 2019, the final year of our analysis. The usage of far-right-denoting terms grew substantially from 2008 to 2014 (243% and 359% in The New York Times and The Washington Post, respectively) and continued to increase from 2015 to 2019 (260% and 128%). These patterns indicate a strong polarizing dynamic arising before Trump, with his arrival in 2015–2016 arguably serving as a reinforcer.

In contrast, far-left-denoting terms did not grow in prevalence in either outlet between 2008 and 2014. However, between 2014 and 2019, the prevalence of such terms increased markedly (328% in the New York Times and 454% in the Washington Post), indicating rising far-left activity in society or a growing concern with the far-left in these moderate left-leaning outlets. Despite the latter increase, the prevalence of far-right-denoting terms in the year 2019 remained almost 4 times higher than far-left-denoting terms in The New York Times and 3 times higher in The Washington Post. The correlation between the right and left political extremism-denoting terms in the two outlet-specific time series is large.

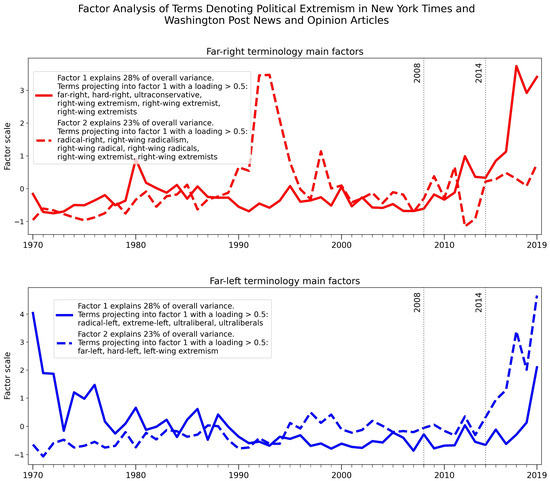

Adding up the relative frequencies of related terms denoting right and left political extremism is useful to quantify the overall prevalence of each theme in the corpus. However, such aggregate metrics can obscure the temporal dynamics of individual terms within the set since the specific dynamics of lower prevalence terms can be masked by terms with larger prevalence. To provide another vantage point of the phenomena under study, we carry out a factor analysis of the target terms for the two newspapers with the longer frequency time-series data available, The New York Times and The Washington Post; see Figure 7. The results confirm our previous conclusions but add detail. The prominence of several terms denoting far-right extremism increased substantially in both newspapers between 2008 and 2014 and then accelerated further post-2014. In the early 1990s, a reduced set of far-right-denoting terms such as radical-right, right-wing radicals or right-wing extremists experienced peak usage coinciding with the deadly sieges at Ruby Ridge, Idaho, in 1992 and Waco, Texas, in 1993. Some far-left-denoting terms such as radical-left decreased in prominence in The New York Times during the early 1970s. Increasing usage of far-left denoting terms picked up again only post-2014 in both outlets.

Figure 7.

Factor analyses of a set of terms denoting right (top plot in red) and left (bottom plot in blue) political extremism in news media articles from The New York Times and The Washington Post. The vertical dotted lines highlight the years 2008 and 2014.

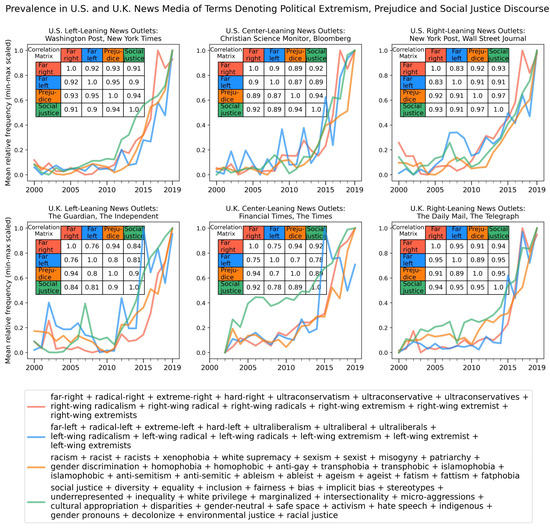

Finally, we note that the growing prevalence of terms denoting political extremism in U.S. and U.K. news media is strongly associated with concomitant trends documented previously (Rozado 2020; Rozado et al. 2021) about the rising use of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in news media content; see Figure 8. The figure shows the most widely read news outlets in our data set with complete and continuous data availability since the year 2000. An exception had to be made for the U.K. center-leaning outlets The Times and the Financial Times, for which online data availability only started in the years 2002 and 2004, respectively.

Figure 8.

Yearly aggregate frequencies (min-max scaled) of sets of related terms denoting right/left political extremism, prejudice and social justice discourse in popular U.S. and U.K news outlets arranged by ideological orientation. The correlation matrix shows the Pearson correlation coefficient between the four time series.

4. Discussion

Our results indicate that the prevalence of terms denoting political extremism in U.S. and U.K. news media has been increasing dramatically since at least 2008 and that this trend is particularly acute for terms denoting far-right extremism. We also noted that the increasing usage of terms denoting political extremism is strongly associated with the previously documented rising prevalence of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse in news media content. This connection suggests the potential existence of a common latent factor simultaneously driving news media’s usage of terms denoting political extremism, social justice discourse and prejudice. Our results also illustrate that mainstream news media is, on average, substantially more likely to use far-right-denoting terms than far-left-denoting terms. A natural follow-up question is the reasons for this disparity.

In chronological terms, the sharp increase in the prevalence of far-right-denoting terms in news media content appears to have begun during the Obama presidency, with very substantial increases in the prevalence of far-right-denoting terms in news outlets between 2008 and 2014. The political emergence of Donald Trump in 2015 might have reinforced this trend. Nevertheless, it is important to emphasize that the growth began prior to the political rise of Donald Trump. This largely parallels the rising prevalence in news media of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse that have been identified as also rising prior to 2015 (Rozado 2020; Rozado et al. 2021).

The biggest limitation of this work is that we cannot elucidate whether the media’s increasing use of terms denoting political extremism is driving, exaggerating or merely responding to concomitant rising political extremism in society. It is conceivable that far-right activity in society could have increased more markedly than far-left activity, justifying news media concern about it. It is, however, challenging to establish an Archimedean point of political neutrality to use as a reference for determining precisely what counts as political extremism.

That is, while it is indisputable that groups which are labeled hard-right have been increasingly prominent in U.S. and European politics, it is also plausible that the center of gravity in established media newsrooms, as in other elite professions (Heterodox Academy 2017), has been shifting leftwards, especially as prestige news media is increasingly organized and edited by graduates from elite universities who tend to hold increasingly socially liberal beliefs (Pew Research 2016). Indeed, journalists have been found to lean left more than the general population (Benson 2005; Call et al. 2021; Dennis 1997; Hopmann et al. 2010; West 2021). Therefore, a plausible explanation for the asymmetry in the prevalence of terms denoting left and right political extremism in news media content could be due to the ideological imbalance in newsrooms that might shape journalists’ choices of political adjectives so as to trigger negative associations with political actors or attitudes that they dislike.

Another potential explanatory factor for the rising incidence of political extremism-denoting terms in news media is the existence of financial incentives for media organizations to maximize the diffusion of news articles through social media channels. It has been demonstrated that user engagement in social media can be increased by news content that triggers negative sentiment/emotions (Hansen et al. 2011). Furthermore, political out-group animosity has been shown to drive engagement in social media-based news consumption (Rathje et al. 2021). Thus, a perverse incentive might have emerged in which news outlets are incentivized to use terminology denoting political extremism to maximize the engagement and spread of their news content through social media.

All of the aforementioned hypotheses (rising political extremism in society, the political biases of news media professionals shaping what gets labeled as political extremism and financial incentives motivating the usage of emotionally charged language) are plausible and consistent with our results on the rising prevalence of political extremism terminology in news media content. Yet, our methodology cannot discriminate among them. This is, therefore, an open question for future research.

An important question raised by our results concerns the social consequences of news media's increasing usage of adjectives denoting extreme political beliefs. If political attitudes are indeed becoming more radical, news media institutions are fulfilling their role of reporting social trends to their readership. If, however, people are not leading the change, but rather newsrooms are responding to economic or ideological factors that incentivize the usage of extreme political adjectives, this could be contributing to rising political animosity in society. The fact that U.K. media trends are similar to those in the U.S. suggests the existence of common factors driving these trends internationally.

A methodological limitation of this work is our inability to control for changes in the language used to signify political extremism. That is, contemporary discourse terminology used to describe political extremism might have undergone semantic shifts compared to previous decades. In addition, different terms employed to signify political extremism might have increased or decreased in popularity over time. While our analysis does not explicitly control for these factors, our usage of different vantage points from which to observe the studied trends, such as factor analysis, allowed us to distinguish increases and decreases in the popularity of specific right- and left-wing extremism-denoting terms over time.

Another limitation of our analysis is the human ratings of outlets’ ideological biases that we used to classify publications as left, centrist or right-leaning. We used static labels for outlets’ ideological bias based on contemporary human ratings. It is possible that some outlets have changed their ideological leanings over time, creating the potential risk of using recent ratings on historical data. However, such changes have probably been rare and relatively mild, like an outlet gravitating from centrist leanings toward left-of-center. Thus, we find it unlikely that such occasional shifts would substantially alter the main findings reported here.

To conclude, we find a rising prevalence in news content since at least 2008, and especially since 2015, of terms that denote extreme left- and right-wing ideologies. This holds in both the U.S. and the U.K., and among left-, centrist- and right-leaning outlets. Furthermore, for at least the past two decades, most news media outlets across the U.S. and the U.K. have tended to use terms that denote far-right political inclinations substantially more often than those pertaining to the far-left. The rising usage of terms denoting political extremism in news media is analogous to the concomitant growing usage of terms denoting prejudice and social justice discourse.

Supplementary Materials

Supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci11040167/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.R. and E.K.; methodology, D.R.; software, D.R.; validation, D.R.; formal analysis, D.R.; investigation, D.R.; resources, D.R.; data curation, D.R.; writing—original draft preparation, D.R. and E.K.; writing—review and editing, D.R. and E.K.; visualization, D.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The analysis scripts, list of written articles’ URLs analyzed and the counts of target words and total words per article are provided as supplementary material in electronic form, DOI: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.5437015 (accessed on 22 March 2022).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- AllSides. 2019. AllSides Media Bias Ratings. AllSides. Available online: https://www.allsides.com/blog/updated-allsides-media-bias-chart-version-11 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Alvares, Claudia, and Peter Dahlgren. 2016. Populism, Extremism and Media: Mapping an Uncertain Terrain. European Journal of Communication 31: 46–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew McGee. 2021. Interactive Media Bias Chart. Ad Fontes Media. Available online: https://adfontesmedia.com/interactive-media-bias-chart/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Bandyopadhyay, Siddhartha, Kalyan Chatterjee, and Jaideep Roy. 2015. Manufacturing Extremism: Political Consequences of Profit-Seeking Media. Working Paper, 2015–03. Birmingham Business School Discussion Paper Series; Nottingham: Nottingham Interdisciplinary Centre for Economic and Political Research. [Google Scholar]

- Baugut, Philip, and Katharina Neumann. 2019. How Right-Wing Extremists Use and Perceive News Media. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 96: 696–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baugut, Philip, and Sebastian Scherr. 2021. The News Expectation Predicament: Comparing and Explaining What Audiences Expect from the Roles and Reporting Practices of Reporters on Right-Wing Extremism. Journalism, 1464884921996307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, Rodney. 2005. American Journalism and the Politics of Diversity. Media, Culture & Society 27: 5–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Betz, Hans. 1998. The New Politics of the Right. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Bruine de Bruin, Wändi, Htay-Wah Saw, and Dana P. Goldman. 2020. Political Polarization in US Residents’ COVID-19 Risk Perceptions, Policy Preferences, and Protective Behaviors. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 61: 177–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caliskan, Aylin, Joanna J. Bryson, and Arvind Narayanan. 2017. Semantics Derived Automatically from Language Corpora Contain Human-like Biases. Science 356: 183–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Call, Andrew C., Scott A. Emett, Eldar Maksymov, and Nathan Y. Sharp. 2021. Meet the Press: Survey Evidence on Financial Journalists as Information Intermediaries. SSRN Scholarly Paper. ID 3279453. Rochester: Social Science Research Network. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Callanan, Valerie J. 2012. Media Consumption, Perceptions of Crime Risk and Fear of Crime: Examining Race/Ethnic Differences. Sociological Perspectives 55: 93–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DellaVigna, Stefano, and Ethan Kaplan. 2006. The Fox News Effect: Media Bias and Voting. Working Paper 12169. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, Everette E. 1997. How ‘Liberal’ Are the Media, Anyway?: The Continuing Conflict of Professionalism and Partisanship. Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics 2: 115–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fawzi, Nayla. 2019. Untrustworthy News and the Media as ‘Enemy of the People?’ How a Populist Worldview Shapes Recipients’ Attitudes toward the Media. The International Journal of Press/Politics 24: 146–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, Lars Kai, Adam Arvidsson, Finn Aarup Nielsen, Elanor Colleoni, and Michael Etter. 2011. Good Friends, Bad News—Affect and Virality in Twitter. In Future Information Technology, Communications in Computer and Information Science. Edited by James J. Park, Laurence T. Yang and Changhoon Lee. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, pp. 34–43. [Google Scholar]

- Heterodox Academy. 2017. The Problem. HeterodoxAcademy.Org. Available online: https://heterodoxacademy.org/problems/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Hopmann, David Nicolas, Christian Elmelund-Præstekær, and Klaus Levinsen. 2010. Journalism Students: Left-Wing and Politically Motivated? Journalism 11: 661–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jardina, Ashley. 2019. White Identity Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Ezra. 2020. Why We’re Polarized. New York: Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Kozlowski, Austin C., Matt Taddy, and James A. Evans. 2019. The Geometry of Culture: Analyzing the Meanings of Class through Word Embeddings. American Sociological Review 84: 905–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Krause, Werner. 2020. Appearing Moderate or Radical? Radical Left Party Success and the Two-Dimensional Political Space. West European Politics 43: 1365–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levy, Ro’ee. 2021. Social Media, News Consumption, and Polarization: Evidence from a Field Experiment. American Economic Review 111: 831–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowry, Dennis T., Tarn Ching Josephine Nio, and Dennis W. Leitner. 2003. Setting the Public Fear Agenda: A Longitudinal Analysis of Network TV Crime Reporting, Public Perceptions of Crime, and FBI Crime Statistics. Journal of Communication 53: 61–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, Gregory J., and Ali Yurukoglu. 2017. Bias in Cable News: Persuasion and Polarization. American Economic Review 107: 2565–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McCombs, Maxwell. 2005. A Look at Agenda-Setting: Past, Present and Future. Journalism Studies 6: 543–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, Muhammad Amir, Hafiz Muhammad Shafiq, and Abdul Waheed. 2017. Understanding regional context of World Wide Web using common crawl corpus. Paper presented at 2017 IEEE 13th Malaysia International Conference on Communications (MICC), Johor Bahru, Malaysia, November 28–30; pp. 164–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Möller, Judith, Robbert Nicolai van de Velde, Lisa Merten, and Cornelius Puschmann. 2020. Explaining Online News Engagement Based on Browsing Behavior: Creatures of Habit? Social Science Computer Review 38: 616–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Müller, Philipp, and Anne Schulz. 2021. Alternative Media for a Populist Audience? Exploring Political and Media Use Predictors of Exposure to Breitbart, Sputnik, and Co. Information, Communication & Society 24: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mutz, Diana C. 2018. Status Threat, Not Economic Hardship, Explains the 2016 Presidential Vote. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 115: E4330–E4339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Norris, Pippa. 2005. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Pippa, and Ronald Inglehart. 2019. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. New York: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Notess, G. R. 2002. The Wayback Machine: The Web’s Archive. Online. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=4370136 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Pew Research, 1615 L. St. 2016. Ideological Gap Widens Between More, Less Educated Adults. Pew Research Center—U.S. Politics & Policy. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2016/04/26/a-wider-ideological-gap-between-more-and-less-educated-adults/ (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Pickard, Victor. 2018. The Strange Life and Death of the Fairness Doctrine: Tracing the Decline of Positive Freedoms in American Policy Discourse. International Journal of Communication 12: 3434–53. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, Steve, Jay J. Van Bavel, and Sander van der Linden. 2021. Out-Group Animosity Drives Engagement on Social Media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 118: e2024292118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rozado, David. 2020. Prejudice and Victimization Themes in New York Times Discourse: A Chronological Analysis. Academic Questions 33: 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozado, David, Musa Al-Gharbi, and Jamin Halberstadt. 2021. Prevalence of Prejudice-Denoting Words in News Media Discourse: A Chronological Analysis. Social Science Computer Review, 08944393211031452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozado, David, and Musa al-Gharbi. 2021. Using Word Embeddings to Probe Sentiment Associations of Politically Loaded Terms in News and Opinion Articles from News Media Outlets. Journal of Computational Social Science, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sides, John, Michael Tesler, and Lynn Vavreck. 2018. Identity Crisis: The 2016 Presidential Campaign and the Battle for the Meaning of America, Illustrated ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Benjamin K., Michael Stohl, and Musa al-Gharbi. 2019. Discourses on Countering Violent Extremism: The Strategic Interplay between Fear and Security after 9/11. Critical Studies on Terrorism 12: 151–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Spanje, Joost, and Rachid Azrout. 2019. Tainted Love: How Stigmatization of a Political Party in News Media Reduces Its Electoral Support. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 31: 283–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Warner, Benjamin R. 2010. Segmenting the Electorate: The Effects of Exposure to Political Extremism Online. Communication Studies 61: 430–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2021. Why Are Journalists so Left-Wing? UnHerd. Available online: https://unherd.com/thepost/why-are-journalists-so-left-wing/ (accessed on 10 February 2022).

- YouGov. 2021. The Most Popular Newspapers in the UK|Media|YouGov Ratings. Available online: https://yougov.co.uk/ratings/media/popularity/newspaper/all (accessed on 1 November 2021).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).