Abstract

As a public space and building, the footbridge is not just a physical concrete building but also carries people’s life experiences and beliefs. In Hong Kong, however, footbridges are a joint product of the government and property developers to control people and drive consumption. Taking the footbridge as an example, this article explores the relationship between public space and the power of discourse. The article first discusses how the government and property developers manipulate footbridges as a social control tool. This article draws on case studies of the use of public space during and after Hong Kong’s social movements in 2019 to discuss how people tried to regain their power of discourse in urban space, and how the government and the bourgeoisie suppressed such attempts. This paper argues that footbridges serve as marginal spaces, and demonstrate power and control by providing a space for people to discuss public affairs and be used to demonstrate power and control, especially in social movements. The footbridges traditionally used are challenged in a social event at the same time, brought under the gaze of planning and management from authorities, on the meaning of public space, the footbridges are narrowed or even prohibited in Hong Kong.

1. Introduction

In modern cities, footbridges are closely related to the living environment and the city’s public space (Wang et al. 2014). Hong Kong has about 1300 underpasses and footbridges (Wang et al. 2014). There are also some mega footbridge networks in Hong Kong, including the footbridge network connecting Central to Admiralty (central business districts in Hong Kong), the one between Mong Kok and Mong Kok East Railway Station (the most densely populated area of the world), and the 5-kilometre-long footbridge network in Tsuen Wan (one of the major shopping areas in Hong Kong) (Tiry 2001; Wang et al. 2016). In residential areas, Tseung Kwan O, known as the ‘City of the Sky’, has many footbridges connecting large housing estates and interlocking shopping malls (Hill et al. 2002). In the planning and urban reconstruction of several new towns, the flows of people and vehicles are completely separated by footbridges. The design of dividing people and vehicles has made the footbridges major constructions of the developments in these districts. Lee (2007) took the urban planning of Tseung Kwan O, a new town in Hong Kong, as a case study and pointed out that Hong Kong lacks public space in the development of new towns. Due to the dense population in Hong Kong, residential areas (or housing estates) are always densely packed with other residential areas and shopping malls that are connected by footbridges between each other. Getting people to cross the road is not the main purpose of footbridges in Hong Kong, as Moir (2002) pointed out, the primary function of the footbridges in Hong Kong is to stimulate consumption by keeping pedestrians in shopping malls, and away from the polluted environment exposed to the driving road.

When the living space is filled with overhead footbridges, the space and power discourses of pedestrians on the ground are taken over by vehicles and highways. The development form dominated by capitalist society also cooperates with the principle of high-altitude development of local real estate developers and consortiums to maximise the benefit of capital gains, making urban planning and construction can only develop towards the sky.

The city itself is not only an object but also a carrier of concepts and norms. By object, it means a reproduction of human culture, while concepts and norms can be social norms, rituals, practices, and politics (Shields 1996). Shields (1991) once examined marginal places, areas distinctive in their cultural distance from the norms of the larger society, and used case studies to demonstrate the importance of the spatial in social practices. Shields (1991) stressed LeFebvre’s notion of space not as an external reality but as a concept that must be understood in terms of the meanings people ascribe to it. Furthermore, Shum (2016) suggested that the experience of the composition of the street proves that space is not merely an integrated existence but a product of society. For example, during Hong Kong’s Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in 2019, footbridges, as marginal space, were not just a physical concrete construction but also carried people’s experiences and beliefs as people stuck posters, slogans, and artworks on the footbridges, making footbridges a battlefield of power and discourse (Hou 2020).

This article aims to reflect on and discuss the role of footbridges as an urban public space, and explore the relationship between space, society, and the power of discourse. This article will first clarify the use of footbridges in Hong Kong and explain footbridges’ practical and social functions in the city. The second part will take Hong Kong, particularly the social movements in 2019, as a case to demonstrate the use of footbridges as public spaces and public domains and to rearticulate and substitute the original meaning of the footbridges, becoming a physical space for citizens’ public and political discussion. The third part will further examine the spatial significance of pedestrian bridges in civil society and the possibility of becoming a public space.

2. Defining Footbridge

The footbridge is a building that assists pedestrians in crossing roads in modern cities. The most common footbridges are those that cross streets or highways, but some footbridges cross rails, light rails, and rivers. The construction of the footbridge can completely separate the pedestrians crossing the road from the vehicles on the road, ensuring smooth traffic and the safety of the pedestrians. Footbridges will also be installed between buildings to facilitate the shuttle between different buildings.

In North America, footbridges are usually owned by businesses and, therefore, not public spaces compared to sidewalks. However, in Asia, such as Bangkok and Tokyo, most footbridges are constructed and owned by municipal governments. These footbridges in Asia connect private railway stations or other means of transport through government-built footbridges and usually run for several kilometres as an elevated walking network in the city. In Hong Kong, footbridges have different names. Some footbridges are called footbridges; some are called skyways or elevated walkways. In order to facilitate the discussion, this article adopts ‘footbridge’ to indicate a pedestrian bridge because the Road Users’ Code in Hong Kong uses this word (Transport Department 2020).

The relevant legislation in Hong Kong for the construction of footbridges is gazetted in the Building Ordinance, which is the only legal basis for regulating and establishing this space (Hong Kong Government 2022a). Under the current Buildings Ordinance, the design of the footbridge is specified by the Practice Notes for Authorized Persons, Registered Structural Engineers and Registered Geotechnical Engineers No. APP-34 (Structural Design of Bridges and Associated Highway Structures) and No. APP-38 (Bridges over Streets and Lanes—Buildings Ordinance Section 31(1)) (Hong Kong Buildings Department 2022). According to these regulations, footbridges can be broadly classified into private and public. The former is supervised by the Buildings Department in accordance with the Buildings Ordinance, while the latter is approved and supervised by the Highways Department. A private footbridge is a building that connects two private properties or one private property and another built on government land. A public footbridge is constructed entirely on government land.

Hong Kong’s footbridges can be traced back to the early 1960s. The first elevated crossing is the Causeway Round Pedestrian Bridge on Yee Wo Street, Causeway Bay, completed in 1963 (Figure 1). According to Shum (2016), the idea of the government at that time was to cope with the rapidly increasing population and rapid economic development of Hong Kong, so pedestrian bridges (footbridges) and pedestrian tunnels (subways) were built to separate vehicular and pedestrian traffic in layers to improve road safety and regulate traffic flow.1 However, when the British-owned land developer Hongkong Land Group obtained the government’s permission to build and manage the footbridge to connect its Mandarin Oriental Hotel and Prince’s Building in 1965 (Figure 2), the development of the footbridge was no longer limited to the separation of people and vehicles but connect the corridors between shopping malls (Shum 2016). Since then, land developers can easily manage the flow of people and promote consumption by building footbridges between their malls and buildings.

Figure 1.

Two banners made by protesters on the Causeway Round Pedestrian Bridge during the Umbrella Movement in 2014.

Figure 2.

The glass-walled footbridge connecting Mandarin Oriental Hotel and Prince’s Building.

Hong Kong adopts the four primary development directions of ‘connectivity’, ‘safety’, ‘accessibility and comfort’, and ‘attraction and vitality’ in pedestrian planning (Planning Department 2021; Yu 2021c). The directions are guided by the policy network formulated by the Planning Department, such as the combination of attracting pedestrians and real estate projects, promoting car-free zones, encouraging developers to reserve pedestrian passages in development projects and urban renewal measures to improve pedestrian flow, the number of flyovers and footbridges has soared (Planning Department 2021). With the cooperation of laws and government policies, it is easy for land developers to build footbridges to connect their development projects. As long as they are constructed in accordance with the policies of facilitating pedestrian access and separating pedestrians and vehicles, the land developers can usually get approval quickly (Shum 2016).

3. From Representations of Spaces to Representational Spaces: The Meaning of Footbridges

Footbridges may have positive effects on people’s mental and physical health. A study in Hong Kong reported that good walking facilities and accessibility relate to the sense of belonging and encourage people, especially older adults, to walk (Yu 2021c). However, more opinions and studies suggest that footbridges have negative psychological effects, especially depression. For example, McCay and Lai (2018) suggested that dense and vertical urban design would affect people’s behaviour and perception of the environment, as well as increase people’s suicidal tendencies. Hong Kong is densely built and lacks green space; these vertical structures, such as malls, commercial buildings, and apartments, would suffocate people if they were connected by closed pedestrian bridges and tunnels.

To make matters worse, the role of pedestrian bridges or footbridges in cities is also a symbol of consumerism and acts as a tool to control people in a mechanical and regulative way. A footbridge seems to be a flowing space, allowing people to flow from one location to another. However, when the pedestrian walk is overhead on the footbridge, it is a restrictive and linearly planned place. Networked footbridges are mall-centric, connecting another shopping mall or transport hub. For Castells (1978), these infrastructures, housing, and transportation are part of the inherent ‘collective consumption’ of capitalism, creating an urban environment conducive to commerce; the space on the footbridge is a consumption space under capitalism as the flow on footbridges, which connect malls, accelerates the flow of capital.

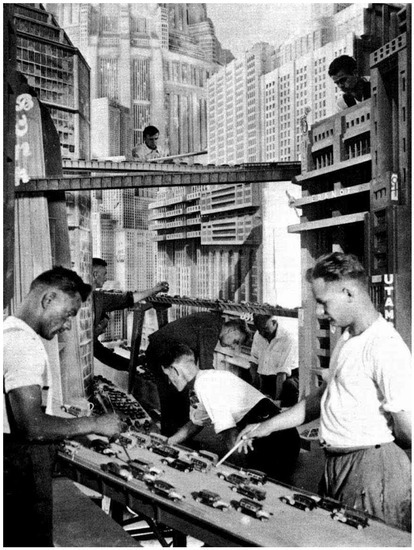

The narrative by Castells (1978) is also a reference to the outlines of urban space presented in the 1927 science fiction film Metropolis by Fritz Lang. The movie presents an imaginary image of the city of the future, with one set depicting a modern metropolis crisscrossed by towering mansions and bridges over elevated skies. Mechanical factories, indifferent and standardised cities, and vertical and geometric compositional buildings form the social order (Figure 3). This vintage film depicts the imagination of the modern city, reflecting the fear of future urban space at that time.

Figure 3.

Behind the scenes of Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, 1927. Source: Public domain.

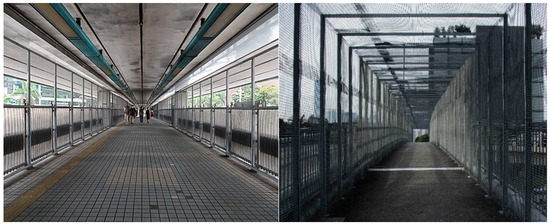

The city presented in the Metropolis is like a standardised cage, and such narrative in the movie can also be seen in the footbridge design in Hong Kong. Since the design of footbridges in Hong Kong is enclosed, the interior of footbridges is usually darker and hotter than the ground. In recent years, especially after the social movement in 2019, the government has even installed barbed wire fences on some bridges to prevent passers-by from throwing objects on the bridge, turning bridges into ‘iron cages’ (Figure 4). This kind of urban design that is dense and lacks open space will reduce the sense of space and freedom, make the already oppressive urban space even more oppressive, and increase depression problems for busy urban people, thus affecting mental health (McCay and Lai 2018).

Figure 4.

Footbridges with barbed wire fences in Hong Kong.

Installing barbed wire fences on footbridges after social movements also shows that footbridges, as a space, are socially and politically constructed. Massey (1994) pointed out that the concept of space involves power and symbolism and the constantly changing composition of social relations. Massey’s insight can be understood as the re-imposition of restrictions on footbridges by the public power, implying further repression in the daily lives of pedestrians. This restriction has specific social and political significance. As Harvey (1994) said, ‘place’ has rich metaphorical meanings; space and place are the structure of discourse. The discourse constructs people’s experiences, memory, desire, and identity (Relph 2008).

Lefebvre (1974) suggested a theory of space and the production of space—representations of space. For Lefebvre (1974), representations of space are technocrats and planners who conceptualised spaces that make society dictated by authority. At the beginning of the article, it was mentioned that the overall pedestrian planning in Hong Kong is preferential treatment for real estate developers; when local real estate developers want to build footbridges, they usually get approval (Shum 2016). Therefore, the identification of lived and perceived spaces by the visions of these technocrats, such as engineers, architects, and planners, who make policies, draft laws, or enforce regulations, is a process of interweaving knowledge and power. In Lefebvre’s words, the process intervenes and modifies the fabric of space infused with adequate knowledge and ideology, and it has an extraordinary influence on the production of space. In capitalist spatial practice, the representations of spaces connecting footbridges facilitate the manipulation of representational spaces, such as enclosed spaces, consumption, waste, and carnival-like situations (Lefebvre 1974).

Chan (2017) also claimed that the footbridge is a top-down spatial production with a set of order and production logic that can effectively restrict the flow and direction of pedestrians by using symbols like arrows. Footbridges make consumption a loop, as the beginning and end of the footbridges connect with malls, making consumption indefinite. In contrast, floor-level pedestrian walkways have higher autonomy; as different from footbridges that connect with different malls, people can explore different side streets, rows, old shops, restaurants, and intersections on the streets. Such interactions on the ground level are impossible as footbridges exploit the autonomy of pedestrians and make the original space (street-level) that connects the real community disappear (Chan 2017). Such disappearance will eventually generate the template of consumption patterns: enclosed shopping malls that stay away from the exhaust gas and cramped, stuffy, and noisy roads (Lau 2009). Traditional communities will disappear, and sole proprietorships will be forced to close. Instead, there are air-conditioned malls and chain stores.

Even so, as a public space, the production meaning of the footbridges is not a stone wall. The meaning of space practice transforms with continuous changes in the users’ experience. The practice of space not only produces social relations but is produced by social relations. Therefore, the following section discusses how footbridges connect with social events and generate specific social relations, as well as the reproduction of space under the bottom-up angle.

4. Challenging the Representations of Space

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt argued that the definition and visibility of public space are interdependent (Arendt 2013). Apart from serving as a physical place for the living experience or acting as a tool to control people in a top-down way, footbridges can be a place of political struggle and wrestling. As a public space, people in Hong Kong have tried to take back the control, discourse, and visibility of footbridges through social and political activities in recent years, subverting the original social functions of the footbridges that were labelled and cast by the coalition of officials and land developers in the city, that are social controls and consumerism (Shum 2016). Anthropologist James Scott also suggested a similar idea in his book Weapons of the Weak: Everyday Forms of Peasant that people can challenge the absolute control of the state through actions in public places (Scott 1986).

The footbridge in Hong Kong has the characteristics of marginality and transition. The social relationship of this fluid space in the city is mainly dominated by ‘representations of space’—that is, technocrats and urban planners—the linear planning model shaped by the bourgeoisie like capitalists and land developers, as well as the barbed wire fences, closed-circuit television cameras, and other restrictions imposed by the state. These representations of space reflect top-down constraints, aiming to prevent proletariats (or semi-proletariats) from getting discourse dominance. Nonetheless, the nature of space is diverse, and space can construct and generate meaning from changing social relationships. We should consider how to practice life experience in these marginal spaces that initially belonged to the people. By challenging the ‘representations of space’, we can gain other possibilities to achieve empowerment. For example, Wong (2018) once surveyed North Point—a district on Hong Kong Island. While it is illegal to gather on footbridges in Hong Kong, Wong found that the footbridge at the Tong Shui Road Market in North Point is a gathering place for Filipino and Indonesian domestic helpers every Sunday. The marginal space on the footbridge has provided them with a rain-proof rest space to gather with other homesick domestic helpers (Wong 2018).

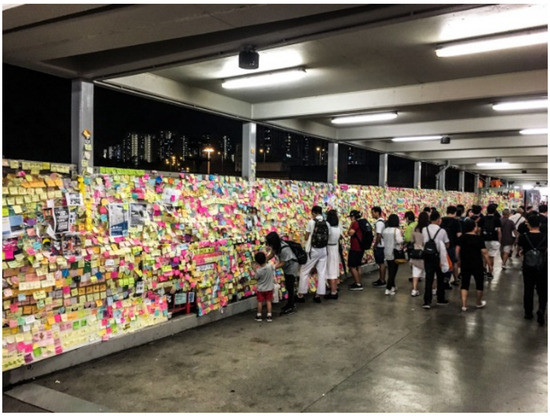

As an atypical and twisted public space controlled by the state, footbridges have rearticulated and reset the meaning of public space in social movements. As said in the introduction, the Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement in Hong Kong in 2019 was an example. During the 2019 Anti-Extradition Law Amendment Bill Movement, there were some public places where public gatherings emerged (either legally or illegally) on the streets of Hong Kong, from street parades or customary gatherings in landmarks such as Edinburgh Place and Victoria Park to traditional political rallies like the 1 July Rally (Purbrick 2019, 2020). However, the function of footbridges is not limited to connecting different sites and buildings. During the social movement in 2019, the meaning of the footbridge was recreated (Hou 2020). The social meaning of footbridges seems to be separated from commerciality in social movements, and there was the possibility of returning the power of discourse to the public. Various community groups held small screenings on some large footbridge networks during the social movement in 2019 (Hou 2020). These footbridge networks are generally crowded and located in busy central business districts and downtowns. This phenomenon made the footbridge—as a fluid space—not only a medium for distributing information but also a space where citizens could stop and communicate with each other.

Spaces with different functions, such as streets, bridges, parks, and squares, become places for expressing opinions, giving full play to civic participation, and breaking through the limitations of the daily use of these infrastructures (Lowe et al. 2021; Liao 2021). Furthermore, some fringe (or marginal) public places, such as subways, footbridges, and bridge pillars under highways, became Lennon Walls, covered by colourful stickers with words supporting the demonstrators during the movement. In these ambiguous and unclearly defined mobile spaces, there are post-it notes with different demands and slogans of the movement, all of which have carried the voices of the people and the expression of social demands (Lowe et al. 2021; Liao 2021). Using the Lennon Walls as a space for collective communication became a specific functional field during the movement (Figure 5). Thus, the inconspicuous marginal public space became a place for regenerating new social meanings during the social movement.

Figure 5.

A footbridge in Central during the social movement in 2019.

Many areas in Hong Kong are dense and crowded, lacking prominent landmarks and public spaces to accommodate large crowds. The general function of these crossing passages, like subways and footbridges, was only a transitional space connecting buildings like malls, transport hubs and housing estates from one another. However, during the social movement, an alternative platform for expressing voices in various ways emerged in the narrow and marginal spaces of the city, such as posting banners, sticking post-it notes, screenings, and public speaking (Lowe et al. 2021; Liao 2021). The restricted pedestrian experience has been rewritten and reproduced through civic actions and social movements with a new meaning of public space (Hou 2020). This new meaning of public space is defined by Hou (2010, p. 2) as ‘the insurgent public space’, meaning civic contestations and informal activity spaces ‘that are no longer confined to the archetypal categories of neighbourhood parks, public plaza, and civic architecture’. Such attempts on the footbridge also explored the alternative functions and possibilities of traditional spaces. The practice of the democratic movement on footbridges not only reinvented the function of space but also proved that social space is dynamic and constituted by constantly changing social relations (Jane and Barker 2016).

Yet, the footbridge is a space of heterotopia that the state has constructed. While footbridges serve as a space on the fringe, providing people with a space to discuss public affairs, footbridges can be used as a tool to showcase power and control, especially during social movements. During the processions, the police always set video cameras on the bridge or use digitised closed-circuit television with facial recognition to monitor citizens’ behaviour from the top, making pedestrians and protestors under the bridge have no place to hide (Purbrick 2019, 2020). Under digital authoritarianism, the entire city has become a cage for the state to monitor and discipline the public, which is conducive to the official prohibition and dispersal of the democratic movement (Foucault 1977). This digital authoritarianism again reflects the footbridge as a tool of power as digital authoritarianism has led to the budding public discourse space re-becoming a space for the state to control the public. Strictly speaking, it is not just a control but a top-down and all-round police-state-style monitor (Castells 1978).

From the case of the footbridge in the social movement in 2019, we can see that there is a diversity of relationships of spaces: intersecting, cooperating, existing, and opposing (Liao 2021). When the government intervenes and regulates footbridges, the footbridge will become a venue for exploited citizens to defend their rights and regain the freedom they should have enjoyed in the public space. Thus, these marginal public spaces have the power of empowerment. However, in late 2019, the Hong Kong government started installing barbed wire fences on footbridges in various districts (Lau and Lou 2019). The added wire acts as an additional political tool to control people and gives the flyover a ‘double oppression’ (Figure 6). The footbridge has become an iron cage-like configuration, transformed into a more closed and suppressive space, and strengthened the suppression in the original solidified flow space, that is, the capitalist social space.

Figure 6.

Police arrest a protester on a footbridge.

The discussion above brings us back to the question: Does public space exist? In The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, Jürgen Habermas referred to the ideal public space as a public square or café in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, where traditional intellectuals could speak, discuss politics, and have freedom of action (Habermas 1991). Many activists (especially protesters in Hong Kong) once expected that Hong Kong’s public spaces, especially flyovers, tunnels, and parks, could be transformed into spaces for public dialogue, just like the social movements in 2014 and 2019. However, Habermas’s introduction to the book has made it clear at the outset that publicity does not necessarily mean accessibility (Habermas 1991). Public buildings or spaces also do not have to be open to the public. It may be public because the building, or space, houses a public authority, such as the government. Of course, whether this government is public depends on whether it is openly elected through a democratic process. Habermas (1991) also pointed out that the importance of public space lies in its role as an intermediary between the private sphere (i.e., a civil society dominated by family life and commodity exchange) and public authority (i.e., the state and the courts).

Footbridges are rare in European countries, and most are uncovered open bridges crossing rivers or rails, such as North Bridge in Edinburgh and the Millennium Bridge in London (Figure 7). Many public spaces in foreign countries allow people to conduct political gatherings and speeches, like Hyde Park in the United Kingdom (Yu 2021a). In Hong Kong, Chapter 132BC (Pleasure Grounds Regulation) of the Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance prohibits citizens from using loudspeakers in parks (Hong Kong Government 2022b; Yu 2021a). Hong Kong’s Public Order Ordinance also prohibits all gatherings in public spaces unless approved by the police. The Public Order Ordinance has a strict definition of illegal assembly:

When 3 or more persons, assembled together, conduct themselves in a disorderly, intimidating, insulting or provocative manner intended or likely to cause any person reasonably to fear that the persons so assembled will commit a breach of the peace, or will by such conduct provoke other persons to commit a breach of the peace, they are an unlawful assembly.(Hong Kong Government 2022c)

Figure 7.

Musicians busking on a bridge in Edinburgh.

The Public Order Ordinance in Hong Kong is a colonial-era law. As long as citizens conduct political activities in public spaces such as parks and footbridges, the government can prosecute the participants for illegal assembly on the grounds that three people gather and affect public order (Kwong 2016). The British government once revised the Public Order Ordinance in Hong Kong in the 1990s to meet the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, but the Ordinance was restored by the Provisional Legislative Council controlled by China after 1997 (Ku 2004).

In his book, Habermas (1991, p. 85) said, ‘[t]he public sphere of civil society stood or fell with the principle of universal access. A public sphere from which specific groups would be eo ipso excluded was less than merely incomplete; it was not a public sphere at all’. In practice, only the well-educated and possessed of assets can enter the bourgeois public sphere. In this way, most members of society are excluded from the public sphere. Historically, it has excluded the poor, women, enslaved people, immigrants, criminals, and other vulnerable groups; In Hong Kong, the open space has excluded ordinary citizens with no political and financial powers. In a sense, the public sphere of Habermas never existed in reality.

The same phenomenon can also be observed in the media. Since the advent of the news, the functions of traditional public spaces have been transferred to mass media. However, in recent decades, the media have gradually lost their checks and balances on society and even the government worldwide because of the support of the capitalists and governing departments (that is, special treatment of news and information for the sake of profit). The rise of the Internet can be said to extend the life of public space in time. At the beginning of the new media era, people had high expectations for online platforms and even felt they could communicate online and offline (Yu 2022b). The unrestricted information release, multiple release channels and multimedia presentations can be said to determine the decline of traditional public space and media public space (Yu 2022b). Yet, in reality, online platforms and new media, such as Facebook and Twitter, have been disappointing in recent years. Many Internet users have found that the government and the owners of these media often cooperate in formulating policies limiting people’s participation in political discussions (Yu 2022b).

5. Conclusions

By understanding the notion of footbridges in Hong Kong city, a preliminary scope view of liquid public space is developed from the reappearance of the meaning of footbridges in Hong Kong’s social movement in 2019. Shields (1996, p. 227) once said the city itself is a representation, and such representation of regional significance is political (see Shields 1996). The use of space is liquified by citizens; out of the footbridges, the civilians utilise the social media platform to extend the ‘rebellious public space’ online. HK Street Observation, an Instagram account created in 2020 with 85,000 followers, has been recording graffiti on the streets, footbridges, floors, and electrical boxes in Hong Kong. Many posts with political sentences and slogans have been posted on the page, such as ‘democracy now’ and ‘come on, Hong Kong people’. Those created public spaces could become a space for expressing political opinions and mobilisation because of people’s co-creation; just like what Hou (2010, p. 2) defined, the insurgent public space is no longer limited to parks and public plazas.

As an insurgent public space and building, the footbridge is, therefore, not just a physical concrete building but also carries people’s life experiences and beliefs. By using the social movement in 2019 as an example, the article points out that citizens in Hong Kong have tried to gain a voice in public spaces on the street. The footbridge became an insurgent public space during the social movement; the value of the footbridge space temporarily strips from commercialisation, which has been discussed in this case study. Footbridges, underpasses, and other forms of walkways, including outdoor escalators, are functional necessities in Hong Kong. However, this article argues that most footbridges, by design, are a joint product of the government and property developers to control people and drive consumption in Hong Kong. After Hong Kong’s handover, accusations of collusion between the government and businessmen have grown stronger. Many social, political, and economic demands of citizens cannot be answered; the government often ignores and suppresses these opposing voices, resulting in a more divided social and political environment in recent years. (Ortmann 2015; Yu 2019, 2021b, 2022a). This article also points out that the new meaning of the footbridges created in the social movement in 2019 was quickly suppressed by the government and the bourgeoisie, such as adding fences and CCTV. Like the movie Metropolis portrayed, Footbridges in Hong Kong are social tools to control and suppress people, making no public space for people to get involved in social affairs but consumerism. As in Habermas’s eyes, modernisation is still an unfinished process, and public spaces are only controlled by the government and bourgeoisie (Cubitt 2005, p. 93).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.K.N.L. and A.Y.; Writing—original draft, S.K.N.L. and A.Y.; Writing—review & editing, S.K.N.L. and A.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | In the Road Users’ Code in Hong Kong, subways mean pedestrian tunnels. Rapid transit (Underground or Tube in London and Subway in North America) is called the Mass Transit Railway in Hong Kong. |

References

- Arendt, Hannah. 2013. The Human Condition. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castells, Manuel. 1978. City, Class and Power. London: Palgrave. [Google Scholar]

- Chan, Ka Ming. 2017. City of Flyovers: Space Reproduction. Available online: https://www.inmediahk.net/node/1052735 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Cubitt, Sean. 2005. Ecomedia. Amsterdam: Rodopi. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, Michel. 1977. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. New York: Vintage. [Google Scholar]

- Habermas, Jürgen. 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Massachusetts: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, David. 1994. From Place to Space and Back again: Reflections on the Condition of Postmodernity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, Juilia, Louis Lam, and Shuet-keung Lo. 2002. Tseung Kwan O Station and Tunnels. HKIE Transactions 9: 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong Kong Buildings Department. 2022. Practice Notes for Authorized Persons, Registered Structural Engineers and Registered Geotechnical Engineers; Hong Kong: Hong Kong Buildings Department. Available online: https://www.bd.gov.hk/en/resources/codes-and-references/practice-notes-and-circular-letters/index_pnap.html (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Hong Kong Government. 2022a. Cap. 123 Buildings Ordinance; Hong Kong: Hong Kong e-Legislation. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap123 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Hong Kong Government. 2022b. Cap. 132 Public Health and Municipal Services Ordinance; Hong Kong: Hong Kong e-Legislation. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap132 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Hong Kong Government. 2022c. Cap. 245 Public Order Ordinance; Hong Kong: Hong Kong e-Legislation. Available online: https://www.elegislation.gov.hk/hk/cap245?xpid=ID_1438402885810_002 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Hou, Jeffrey. 2010. Insurgent Public Space: Guerrilla Urbanism and the Remaking of Contemporary Cities. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, Jeffrey. 2020. Be Water, as in Liquid Public Space. Hong Kong: Medium. Available online: https://houjeff.medium.com/be-water-as-in-liquid-public-space-8148a2c80026 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Jane, Emma, and Chris Barker. 2016. Cultural Studies: Theory and Practice. London: Sega. [Google Scholar]

- Ku, Agnes Shuk Mei. 2004. Negotiating the space of civil autonomy in Hong Kong: Power, discourses and dramaturgical representations. The China Quarterly 179: 647–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Kwong, Ying-ho. 2016. State-society conflict radicalisation in Hong Kong: The rise of ‘anti-China’ sentiment and radical localism. Asian Affairs 47: 428–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, Chris, and Zoe Lou. 2019. Fences Added to Footbridges to Stop Protesters Throwing Objects onto Roads. Hong Kong: South China Morning Post. Available online: https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/politics/article/3043742/metal-fences-added-hong-kong-footbridges-stop-protesters (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Lau, Wai Sze. 2009. Malls Such as Battlefields—Deconstructing Consumption and Symbols. Hong Kong: Cutural Studies@Lingnan. Available online: https://www.ln.edu.hk/mcsln/archive/13th_issue/feature_02.shtml (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Lee, Chiu-yun. 2007. Public Space in Tseung Kwan O. 2007 Annual Syposium: Privatising Public and Private. Available online: https://www.ln.edu.hk/cultural/mcs/materials/Sym%202007/5_P3.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Lefebvre, Henri. 1974. The Production of Space. London: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, Sara. 2021. Feeling the 2019 Hong Kong anti-ELAB movement: Emotion and affect on the Lennon Walls. Chinese Journal of Communication 3: 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowe, John, Hsun-Hui Tseng, and Stephan Ortmann. 2021. Photo essay: Reclaiming the university–Cartographies of student resistance during the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests. Asian Affairs 52: 344–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, Doreen. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCay, Layla, and Larissa Lai. 2018. Urban design and mental health in Hong Kong: A city case study. Journal of Urban Design and Mental Health 4: 9. [Google Scholar]

- Moir, Nicola. 2002. The Commercialisation of Open Space and Street Life in Central District. Hong Kong: Civic Exchange. [Google Scholar]

- Ortmann, Stephan. 2015. The umbrella movement and Hong Kong’s protracted democratisation process. Asian Affairs 46: 32–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planning Department. 2021. Hong Kong Planning Standards and Guidelines; Hong Kong: Planning Department. Available online: https://www.pland.gov.hk/pland_en/tech_doc/hkpsg/full/index.htm (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Purbrick, Martin. 2019. A report of the 2019 Hong Kong protests. Asian Affairs 50: 465–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purbrick, Martin. 2020. Hong Kong: The torn city. Asian Affairs 51: 463–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relph, Edward. 2008. Place and Placelessness: Research in Planning and Design Series. London: Pion Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, Jim. 1986. Everyday forms of peasant resistance. The Journal of Peasant Studies 13: 5–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, Rob. 1991. Places on the Margin: Alternatives Geographies of Modernity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Shields, Rob. 1996. A guide to urban representation and what to do about it: Alternative traditions of urban theory. In Re-Presenting the City. London: Palgrave, pp. 227–52. [Google Scholar]

- Shum, Tak-sing. 2016. The City of Footbridges. Hong Kong: Cutural Studies@Lingnan. Available online: https://www.ln.edu.hk/mcsln/archive/55th_issue/pdf/Key_Concept.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Tiry, Corinne. 2001. Hong Kong’s future is guided by transit infrastructure. Development 17: 28–35. [Google Scholar]

- Transport Department. 2020. Road Users’ Code; Hong Kong: Transport Department. Available online: https://www.td.gov.hk/filemanager/en/content_172/road_users_code_2020_eng.pdf (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Wang, Weijia, Kin Wai Michael Siu, and Kwok Choi Kacey Wong. 2014. Loose Space, Inclusive Life: A Case Study of Mong Kok Pedestrian Bridge as an Everyday Place in a Densely Populated Urban Area. International Journal of the Constructed Environment 5: 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Weijia, Kin Wai Michael Siu, and Kwok Choi Kacey Wong. 2016. The pedestrian bridge as everyday place in high-density cities: An urban reference for necessity and sufficiency of placemaking. Urban Design International 21: 236–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, Sampson. 2018. Ways of Urbanist Seeing. Hong Kong: Mingpao. Available online: https://m.mingpao.com/ldy/cultureleisure/culture/20180225/1519496244893 (accessed on 28 August 2022).

- Yu, Andrew. 2019. Harmony and discord: Development of political parties and social fragmentation in Hong Kong, 1980–2017. Open Political Science 2: 53–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Andrew. 2021a. Open space and sense of community of older adults: A study in a residential area in Hong Kong. Archnet-IJAR: International Journal of Architectural Research 15: 539–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Andrew. 2021b. The failure of the welfare ideology and system in Hong Kong: A historical perspective. Human Affairs 31: 99–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Andrew. 2021c. Walkable environment and community well-being: A case from the city of Kwun Tong. Open House International 46: 162–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Andrew. 2022a. Hong Kong, CANZUK, and Commonwealth: The United Kingdom’s Role in Defending Freedom and the Global Order under ‘Global Britain’. The Round Table 111: 516–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Andrew. 2022b. The Internet’s role in promoting civic engagement in China and Singapore: A Confucian view. Human Affairs 32: 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).