Abstract

Social and material models consider hyperconsumption to be an unsustainable practice of consumer behavior that is responsible for the considerable damage inflicted upon the planet. The primary objective of this research study was to develop and validate a novel measurement scale to assess hyperconsumption behavior (HB) from a consumer’s point of view. Based on the literature on measurement theory, an HB scale was developed and validated over three studies. The first study consisted of item development, while the second study focused on exploring and confirming the factor structure of the scale. The investigations revealed that hyperconsumption behavior was a first-order construct with four underlying dimensions: shopping control (food); perceived repair benefits; possession of a large amount of goods; and experiential consumption. The third study assessed the nomological validity of the proposed scale by testing its association with two relevant scales of materialism and sustainable purchase behavior.

1. Introduction

The depletion of non-renewable energy sources, climate change, the rapid increase in the absolute numbers of the population, and unsustainable consumption practices inflict environmental damage worldwide (). Global population growth and materialistic lifestyles are increasing the global demand for goods and services, thereby leading to unlimited hyperconsumption (). In response to growing consumption, companies increase their production, eventually causing environmental damage. Even if considerable improvement in the production process efficiency is achieved, a successful approach to environmental problems would involve different measures and actions aimed both at the transition to sustainable production and at the restriction of unsustainable hyperconsumption practices.

Hyperconsumption is related to the development of a hypermodern society since the beginning of the 20th century. The very transformation of the post-modern society into a hypermodern one has been an important topic for different social sciences, such as philosophy, sociology, psychology, and economics (; ; ). A hypermodern society is a liberal society characterized by “high-speed movement”. It is expressed through the idea of a life “marked by a climate of immoderation, exacerbation, and forward-fleeing” () and is dominated by modernity in excess. Whereas the modern age functions through a well-arranged and systematic routine, the hypermodern phase favors the autonomy of disorder and deregulation in the different domains of individuals’ everyday lives. Therefore, the hypermodernity concept involves “hyper” dimensions in all spheres of modern life, such as hyper-terrorism, hyperpower, hyperconsumption, hyperproduction, hyperactivity, hyper-capitalism, hyper-technification, hyper-individualism (, ), hyper-narcissism (), hyper-performance () and hyper-change ().

According to (), the post-modern society of the second half of the 20th century has already been transformed into a “hyperconsumption society”. The hyperconsumption society is “itself a vehicle for a veritable explosion of individualism, a hyperindividualism; with multiequipping allowing independent activities; individualized consumerism; personalized use of space, time and goods”. If, previously, one used to consume in order to live, what really matters in a hyperconsumption society is consumption itself: consuming here and now, without any restriction or restraint in the search for unattainable individual happiness solely through consumption. It seems that Descartes’ famous maxim “I think, therefore I am” has been transformed into “I consume, therefore I am”, presenting the newest version of the Cartesian understanding of existence (; ; ; ). However, the interpretation of this transformation is not unequivocal. Thus, () considered consumption as “an outcome of individual emancipation”. To them, “consuming may set us free, but freedom leads us to consume”. () treats consumption as an activity that “provides people with the basic certainty of their existence” and believes that the slogan “I consume, therefore I am” is “applicable to all consumers in modern society”. The criticism of the domination of consumption is mainly directed towards its profound negative consequences (). () contends that “in an era advocating nonsense and frivolity”, excessive consumption is produced, and this is consumption without a substantially positive meaning since human needs cannot be satisfied by excessive consumption. More and more frequently, thoughtless waste and extravagant consumption practices hide mental diseases and social problems. () warns that market economies, driven by a desire for consumption and possession, portend an environmental crisis. He sees the operational logic of “I consume, therefore I am” in “Not giving but consuming”. Behind this consumer mentality, there is the desire for a maximum increase in the quantities of the world’s possessed goods. While the people in some countries consume the planet’s non-renewable resources recklessly and uncontrollably, millions of other human beings cannot even meet their most basic needs.

Evidently, the demand for restricting high consumption levels is most relevant to consumers in rich countries (); therefore, numerous policies have been used in recent years to reduce the environmental footprint at the international and European levels. Some achievements have been registered with regard to this key challenge. The scholarly discussion from a sustainability-centric perspective has increased. Prior research examined aspects such as collaborative consumption (), economically sustainable consumer choices (), pro-environmental consumption (; ; ; ), ethical consumer behavior (), responsible consumption (), etc. However, there is a huge gap regarding the physical manifestations of unsustainable consumer behavior. Although some authors regard hyperconsumption as an inevitable necessity and demand that people “stop demonizing the world of hyperconsumption” (), the present study examines hyperconsumption as unsustainable behavior when the act of hyperconsumption has negative impacts on the ability of the environment to meet the needs of future generations.

There are significant bodies of literature that have focused attention on hyperconsumption as a central feature of a hypermodern society (; ). Previous research discussed the negative effects of hyperconsumption (; ; ) but did not attempt to suggest structural dimensions for measuring hyperconsumption behavior. A possible explanation for that is that the hyperconsumption phenomenon has a complex, multi-aspect nature that is not easily measurable due to its numerous social and economic forms that affect, directly or indirectly, a wide range of stakeholders. For instance, () reviewed two occurrences of hyperconsumption in daily life, transport and eating or “fast cars/fast foods”, and warned that the hyperconsumption of cars and foods added significantly to the ecological impact of human activity and contributed to the naturalization of a way of life. () focused on the hyperconsumption implications on fashion trends and brands. () emphasized that the consumer society development led to a transformation in politics, which turned into an object of hyperconsumption (mainly through mass media). Therefore, hyperconsumption practices are everywhere and are part of everyday life. Furthermore, hyper-consumers include not only individuals but also manufacturers (e.g., via the use of technologies requiring increased energy consumption) and retailers (e.g., via the purchase of large amounts of food products with short shelf lives, which are impossible to sell and eventually generate food waste). Without underestimating the work conducted by various authors on the conceptual clarification of hyperconsumption manifestations and the effects so far, we believe that there is a need for further research and examination on hyperconsumption behavior (HB). Our study makes a contribution to the existing literature by defining the HB construct and offering a valid and reliable framework for its measurement. It is the first attempt to develop a reliable and valid scale for HB measurements from a consumer perspective. We chose this perspective for the development of the scale not only because the literature underlines the key role of the individual hyper-consumer in a “hyperconsumption society” (; ) but also because we believe that individual consumers are equal participants and have to play an active role in the general commitment to the environment. Frequently, their growing needs and desires demand an increase in the manufacture and supply of goods and services, which in turn lead to the depletion of the natural resources, to pollution and to the deterioration of the environment’s quality. Hence, the provision of a tool for the measurement of hyperconsumption consumer behavior is not only a matter of purely academic interest but also a possible contribution to public institutions, business enterprises, non-governmental organizations and other stakeholders, which could take measures and actions towards a reduction in hyperconsumption and encourage responsible consumer behavior.

2. Theoretical Conceptualization

2.1. Hyperconsumption Behavior

For the purpose of the definition and outline of the dimensions of the HB construct, a review of scientific journal articles, e-Books and conference proceedings was conducted in various electronic databases, such as Scopus, Science Direct, ProQuest and Google Scholar. Several keywords were used to search for most relevant publications, including “hyperconsumption”, “hyperconsumption behavior”, “overconsumption”, “unsustainable consumption”, “unsustainable consumption behavior”, “irresponsible consumption”, etc. A cursory review was carried out to evaluate the articles in regard to hyperconsumption from a socio-economic and environmental perspective. It was found that most publications regarded hyperconsumption on a conceptual level and did not offer a valid framework for measuring the HB construct.

In the existing literature, there is lack of agreement on the definition of hyperconsumption. For instance, according to (), hyperconsumption needs to be considered as a manifestation of a different market logic. It is composed of two phenomena. On the one hand, the consumption of material goods occupies an increasingly larger part of social life. On the other hand, consumption itself is becoming more emotional and hedonic, overcoming the symbolic social confrontations described by Bourdieu. This means that people consume mainly because of the hedonic aspect of consumption, in which they find pleasure, entertainment and meaning, rather than for the demonstration of status or competition with others. That is, in Charles’ view, the individual and entertaining value of consumption exceeds the symbolic and status value. () define hyperconsumption by “heightened levels of individual and collective obsession”. Lipovetsky and Serroy (as cited in ), in turn, regard hyperconsumption as “one that is highly individualized, erratic, and emotional, and carried out in a sprawling retail universe where to consume is not just an aspect of life, perhaps a point of social prestige, but is life itself: in a universe where to exist is to consume”. Hence, (1) hyperconsumption is emotional, hedonic and psychosomatic; (2) it plays a certain therapeutic role for individuals who consume in order to fill a void in their lives; (3) the boundaries of the social aspect of consumption are fuzzy insofar as consumption is no longer a matter of social status or class culture. () suggests that hyperconsumption refers to the consumption of goods and services for non-functional purposes, i.e., “consumption is not a means to other ends but becomes the end in and of itself”. Similarly, () also contends that hyperconsumption is often defined as the extreme maximalist consumption of goods/commodities for non-functional purposes. On the other hand, () points out that hyperconsumption connotes consumption where the ecological referent is obscured—consumers are no longer aware of the natural resources used in the manufacture of goods. () state that hyperconsumption exists on two related levels: there is speeded up consumption (a matter of pace) and there is greater consumption (a matter of intensity).

The social and material hyperconsumption models affect various aspects of people’s lives. Table 1 presents different physical manifestations/forms and effects of hyperconsumption identified as a result of the literature review.

Table 1.

Physical manifestations and effects of hyperconsumption.

Regardless of the lack of a single definition of hyperconsumption, the key phrases that define the notion can be generalized as follows: “acquisition of large amounts of goods”; “cult of novelty”; “individualism”; “high speed of purchase decision making”; “pursuit of happiness”; “purchase of goods for non-functional purposes“; “strong desire for experiencing pleasure”; “high frequency of the manifestation“; “hedonic delight in consumption”; “hedonic behavior unrelated to social status” and “psychosomatic effect“.

In our opinion, the two notions, “hyperconsumption behavior” and “hyperconsumption”, should not be used interchangeably since they differ both in content and in coverage. They stand in a part–whole relationship. Hyperconsumption is a generalized notion that functions as a macro-frame. For instance, hyperconsumption can be observed with individuals with a particularly strong desire to be informed (e.g., watching television programs all day for the purpose of being well-informed) and with people who have an overwhelming desire to create social contacts (e.g., by joining various and numerous social communities in social networks). The “hyperconsumption behavior” of consumers is related to the accepted consumer behavior model with regard to some goods that turn into the objects of hyperconsumption. That is, the act of acquiring goods and services through purchasing underlies this behavior. Furthermore, in order to study this type of behavior, we have adopted the notion of “hyperconsumption” introduced by the French philosophical school of thought, regardless of the possibility of HB overlapping with other terms used in the literature, e.g., “overconsumption” (; ; ) or “high consumption” ().

Taking into account the “hyperconsumption” key words identified by us and the meaning of the combining form “hyper” that signals excessive, constant, overreaching, maximum and extremities (), we would suggest the following definition for hyperconsumption behavior: consumer behavior characterized by increased levels of the acquisition of goods and services for satisfying non-basic needs at high speeds and frequencies of occurrence. To us, HB as a construct presenting actual occurrences of hyperconsumption has at least four dimensions: shopping control; perceived repair benefits; the possession of a large amount of goods; and experiential consumption. Furthermore, being an unsustainable practice, HB is driven by an uncontrollable, strong desire that ignores the social, ethical and ecological effects of the purchase decision made.

2.1.1. Shopping Control (Food)

The excess consumption of foods rich in fats, salt and sugar and of ultra-processed products is one of the reasons for the occurrence of overweight and obesity. Obesity in early childhood or adolescence or among working age individuals has irreversible consequences later in their lives: They develop diseases such as diabetes mellitus, arterial hypertension, high cholesterol and triglyceride levels, joint or respiratory disorders, etc. (). However, this is only one aspect of the problem related mainly to consumers’ eating habits. The other aspect is hyperconsumption behavior, which causes food waste. Research indicates that “households, and thus, consumers, are the biggest food waste producers” (). The purchase of large amounts of food is the most frequently discussed hyperconsumption practice in the literature (; ; ; ). Food loss and waste due to the purchase of food amounts that are too large to be eaten are global problems with financial, ecological and social implications that need to be solved urgently in view of the forecasts for a high world population growth rate (by over 30% to around 9.3 billion people in 2050) (). On a European level, an ambitious goal was formulated for waste reduction by 30% until 2025 and by 50% until 2030 in the territory of the entire EU. The EU Code of Conduct on Responsible Food Business and Marketing Practices () emerged as a significant part of EU’s efforts directed to the enhancement of sustainability in the food sector.

The predominant view in the literature is that the decision-making for the purchase of large amounts of food is determined by the consumers’ inability to apply self-control while shopping (; ).

Shopping control (SC) is defined as a consumer’s ability to resist the desire for purchasing larger amounts of food than needed. Consumers with lower SC levels tend to waste more food. More specifically, SC reflects three dimensions: food-related routines; marketing/sale addition and perceived behavioral control. Basic routines, including the act of grocery shopping, can have a significant effect on food waste (). Marketing/sale addition relates to marketing and sales strategies (such as the layout of goods and special offers in supermarkets) that can further affect consumers’ behavior (). The perceived behavioral control represents the beliefs of individuals regarding the difficulty of reducing their food waste behavior (; ).

2.1.2. Perceived Repair Benefits

According to (), the constant pursuit of novelty is a relevant feature of every hyper-consumer. In hyperconsumption, () found a cult for novelty and pointed out that it was mainly due to: (a) the accelerated supply of disposable goods; (b) planned obsolescence; (c) breakthrough innovations that replace previous technology and d) fashion trends followed by consumers.

The academic literature on the circular economy strategy describes repair as an essential factor in extending the lifetime of products (). Numerous studies focused on barriers to both the supply of and demand for repair. For instance, () outlined a wide range of fundamental obstacles relative to the performance of repair activities in the EU and U.S., such as the Intellectual Property Law (e.g., patents, copyrights, design, and trademarks), Consumer Law (warranties and guarantees), Contract Law (e.g., end-user license agreements and sales contracts), Tax Law and Chemical Law, along with issues of design, consumer perceptions and markets. Cooper and Salvia (as cited in ) classified the barriers to repair into three categories: “barriers related to the product and poor design”; ”propensity and the ability of the owner to repair products” and “barriers related to the context”. Regardless of the nature and scope of the different barriers, however, as () and () suggested, in the end, the decision to repair is dependent on the consumer’s choices and perceptions. The reasons for the choice of non-repair that are most frequently identified in the scientific literature are financial expenditure, a lack of time, lack of trust in the quality of the repair services provided (), higher repair price compared to the price of a newly purchased item and perceived repair difficulty ().

Perceived repair benefits (PRBs) are used herein to refer to an individual’s positive perceptions of the repair services associated with preferences for the possibility of repair rather than the purchase of or replacements with a new item in the event of non-compliance (with the sales agreement and the provisions related to the product use).

2.1.3. Possession of Large Amounts of Goods

Hyperconsumption is manifested in the personal possession of larger amounts of material goods, such as home appliances, clothes, shoes, electronic devices, automobiles, etc. (; ; ). The effects of the manufacture and planned obsolescence of these products on the environment are well-known. Thus, the impacts of the fashion industry include over 92 million tons of waste produced per year and 79 trillion liters of water consumed (). The amount of waste electrical and electronic equipment (WEEE or e-waste) has become the fastest growing category of waste in developed countries, a matter of concern in developing countries and is expected to double by 2050 (). It is important to emphasize the role of consumers’ choices but the responsibility for the encouragement of these choices lies with the manufacturers and traders.

The indicator of an HB manifestation via the possession of large amounts of goods (PLAG) used in our study is the level of the amounts of goods possessed, which are (1) used according to their intended purpose and (2) are not used according to their intended purpose but are stored, although they have not lost their ability to perform their functions.

2.1.4. Experiential Consumption

To (), the hedonic measurement of consumption is best illustrated by the growing role of leisure industries (tourism, amusement parks, video games, theme festivals, tank driving, igloo accommodation, etc.) in our societies. They offer multiple opportunities to experience entertainment and shows, games, tourism and relaxation. In this context, hyper-consumers not only seek to possess things but also to multiply their experiences and to experience because of the experience itself and because of the feeling of elation and new emotions. The utility of a hedonically based purchase decisions refers to aesthetic or sensual pleasure, arousal and excitement from a choice (). Unlike physical goods, hedonic consumption is experiential in nature and does not involve ongoing ownership and continued usage (). Perhaps this is what makes hedonic consumption less responsible for the infliction of considerable damage on the planet, but consumers’ addiction to tourist air travel (for instance), leading to excessive flying, has destructive outcomes with respect to the environment in view of climate change (). Visits to various events may create heavy environmental pressure via the use of different modes of transport, the generation of waste from catering facilities, the use of local resources, such as energy, food and other raw materials that may already be in short supply, etc. ().

Experiential consumption (EC) emphasizes the emotional and hedonic qualities in the marketplace and refers to consumption as a legitimate method of generating interesting and relevant experiences ().

3. Development of a Scale to Measure Hyperconsumption Behavior

In order to develop a scale for hyperconsumption behavior, three empirical studies were conducted. First, in Study 1, we generated an initial pool of items using a literature review, focus group discussions and in-depth interviews and had them validated by content experts. In Study 2, we conducted exploratory factor analyses (EFA) to achieve the final items and consider the underlying constructs, which was verified by subsequent confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) performed with the assistance of structural equation modeling. After the EFA, we ended up with a 14-item hyperconsumption behavior scale consisting of four factors. To assess the nomological validity of the new scale, we investigated the relationships of hyperconsumption behavior with existing, relevant scales of materialism and sustainable purchase behavior in Study 3.

3.1. Study 1: Item Generation

After a cursory review of the literature, an initial pool of potential items was generated. In line with other publications on scale development (e.g., ; ; ), a qualitative study was conducted to provide a deeper understanding of the phenomenon of hyperconsumption behavior. Two focus group discussions (FGD) and 15 in-depth interviews (IDI) were conducted in this regard. Ten members were included in each FGD. The profile of the participants in the FGD and IDI is shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of the focus group discussion and in-depth interview participants.

The two FGDs were conducted in person (in compliance with the anti-COVID-19 restrictions that are in effect in the territory of the country) in lecture halls at a Bulgarian academic institution. The IDI participants were contacted via e-mails and phone calls. All respondents volunteered to participate in our survey. Semi-structured questions were used. In accordance with the approach applied by (), we formulated the following questions:

- What do you know about hyperconsumption behavior?

- How do you perceive HB?

- (Upon providing the HB definition) Do you agree with this definition? If yes, why? If no, why? Please explain further;

- In your opinion, how many domains do you think HB should have? Please explain further;

- (Upon providing the list of HB items). Do you think these items are in-line with the HB definition? If not, which items do you think need to be deleted and why?

- Could you please suggest some more items that reflect HB?

- After completion of the FGD and IDI, 34 items for measuring SC, PRB, PLAG and EC were generated.

Table A1 (Appendix A) presents the four constructs of the scale we developed for measuring HB. We adopted the name “shopping control” for the SC construct as suggested by (). However, we adapted SC so that it would meet the objectives of our study by taking into account the work of (); (); (); and (). To measure the respondents’ shopping control, seven items were used in three dimensions: food-related routines; marketing/sale addition; and perceived behavioral control. We included three items for the purpose of assessing the participants’ food-related routines (SC1, SC2, and SC3). The marketing/sale addition was measured using two items (SC4 and SC5). The degree of difficulty the participants expected to encounter in reducing their food waste (perceived behavioral control) was assessed using two items (SC 6 and SC7).

The “perceived repair benefits”, “possession of large amounts of goods” and “experiential consumption” constructs were developed by the authors of this study especially for its purposes and corresponded to the hyperconsumption objects established in the literature, such as clothes, electrical appliances, real property, shoes, cell phones, books, electronic gadgets, toys, skincare products, cars, travel, entertainment, etc. PRB, which represents the respondents’ attitude to repair and their new product-purchasing practices, was measured using nine items (PRB1–PRB9). PLAG was measured using eight items (PLAG1–PLAG8) and referred to the possession of large amounts of goods that exceeded the participants’ basic needs on the one hand but were used according to their designation (for instance, through the following statements: “I pride myself on the wide variety of accessories I possess” and “I have so many skincare products that I will not be able to use them before their expiry dates”). On the other hand, they were stored; i.e., they were not used according to their designation (for instance, through the following statements: “I have a lot of clothes that I have never worn” and “I have too many shoes that I do not wear”). EC was measured using nine items (EC1–EC9), which demonstrated the respondents’ inclination towards and practices of hyperconsumption related to the shared experience of places and events.

To further ensure the content validity of this measurement scale, a list of items generated from the FGD and IDI was sent to five experts who were asked to rate the 34 items along a 5-point evaluation scale in terms of representativeness, specificity and clarity (similarly to ). The required threshold for an item to remain was that it would score above three out of five in all categories. The demographic profile of these five experts has been shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic profile of the content validity experts.

The experts were chosen with regard to their expertise in the specific substantive area of the construct. We believe that content validity was secured through this procedure. The experts’ overall feedback on our HB items was positive and the different perspectives towards hyperconsumption that were included in the items were considered relevant for the HB scale. As a result, 6 items were deleted, and finally, 28 measurement items were retained for the data collection. The questionnaire used a 7-point Likert-type scale (1 = extremely agree and 7 = extremely disagree).

3.2. Study 2: Exploratory and Confirmatory Factor Analysis

3.2.1. Study Sample

In order to collect the data, a web-based survey procedure was conducted with the help of a certified sociological agency operating in Bulgaria. A quota sampling approach was employed to provide a representation of the sample by considering the following predetermined quota characteristics: gender; age groups and place of living in administrative territorial regions in the country. The sample reproduced the structure of the population in Bulgaria as of 31 December 2020 (in conformity with the data published by the National Statistical Institute in the Republic of Bulgaria). We chose Bulgaria as a case study for the following reasons. Firstly, the Republic of Bulgaria belongs to the category of European countries with post-communist transition economies that were once communist but underwent a dramatic shift from Soviet-style central planning to capitalist-style market liberalization in the early 1990s. In an observation made with regard to East Germany but that is also perfectly valid for and applicable to Bulgaria, () pointed out that under planned economies, there had been a constant deficiency of consumer goods that forced people into spending time and energy on acquiring the most fundamental items, whereas the transition to a market economy led to the introduction of new brands and a flood of advertising and retail outlets. The existence of a “communist footprint” as an ideological stamp from the external environment () affects the consumption patterns of Bulgarians; still, similar to the other post-communist countries, Bulgaria quickly shifted from a planned economy to a demand economy and formed its current hyper-consumer society within a short period of time. Unlike the Western world, which passed through different stages of consumer culture gradually, over nearly a century (), in Bulgaria and other former socialist countries hyperconsumption reached its current phase in only a few decades. Secondly, being a full-fledged EU and United Nations (UN) member, Bulgaria shares the responsibilities of governments and all stakeholders for the achievement of the UN Global Goals (Sustainable Development Goals, or SDGs), including SDG12, which aims to ensure responsible consumption and production patterns. Bulgaria’s first Voluntary National Review of the implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals () outlines the challenges faced by the country in relation to SDG12, namely, food waste per capita and the need for raising the awareness of students, their families and the public as a whole regarding environmental protection and ecological balance.

The final sample consisted of 708 valid responses after the deletion of the observations with missing values and straight lining (Table 4).

Table 4.

Socio-demographic profile of the sample (n = 708).

Afterwards, the full sample of 708 participants was divided randomly into two sub-samples. The smaller sub-sample (n = 338) was analyzed using exploratory factor analysis, and the larger sub-sample (n = 370) was analyzed using confirmatory factor analyses. The gender, age and administrative division ratio was preserved when the split was made. Results of chi-square tests of independence indicated that the participants in the two sub-samples were not statistically different with regard to the selected characteristics. Hence, the results suggested that the random split assignment was appropriate.

3.2.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted in Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 26 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to reduce the number of items and to test the dimensional structure of the HB scale (HBS). The ratio of the sample size to the number of items in EFA was approximately 12:1. The normality of the data was not violated since the threshold of the absolute skewness value and absolute kurtosis value did not exceed 2 and 7, respectively (). Hence, the maximum likelihood extraction method was used in compliance with the recommendations concerning the future use of the measures with other datasets (). Promax rotation with Kaiser normalization was applied because oblique rotations allowed factors to be correlated (; ), as was expected in the present study.

Following the current recommendations (; ) and including the avoidance of cross-loadings, factor loadings less than 0.4 and communalities less than 0.2, we removed fourteen items. Thus, the initial pool of 28 items was reduced to a final set of 14 items.

The factorability of the data was provided via the determinant of the correlation matrix, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) measure of sampling adequacy and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (). The determinant of the correlation matrix was 0.001, indicating the absence of high intercorrelations among the items. The KMO was 0.872 corresponding to “meritorious” on Kaiser’s classification of measure values (). Bartlett’s test of sphericity was statistically significant (χ2 (91) = 2432.3, p = 0.000), showing once again that the data were probably factorizable.

Based on eigenvalues greater than one and a scree plot test, the EFA revealed a four-factor solution that explained 73.57% of the total variance. The first factor, shopping control, explained 40.45% of the variance (eigenvalue = 5.63). The second factor, perceived repair benefits, accounted for 12.59% of the variance (eigenvalue = 1.76). The third factor, the possession of large amounts of goods, explained 8.51% of the variance (eigenvalue = 1.19). The last factor, experiential consumption, explained 10.02% of the variance (eigenvalue = 1.68).

The internal reliability of these extracted four factors was assessed with the help of Cronbach’s alpha. All values of Cronbach’s alpha for the distinct dimensions of HB exceeded the cut-off value of 0.70 (); thus, the internal reliability was established. Table 5 and Table 6 show the results of the descriptive statistics and EFA, respectively.

Table 5.

Descriptive statistics of the final items.

Table 6.

Results of EFA.

Harman’s single-factor test was performed to test for common method bias (CMB). The result, based on the unrotated principal axis factoring, revealed that the first factor explained 37% of the total variance, which was less than the critical value of 50% (; ). Henceforth, CMB was not a concern in the present study.

3.2.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

To validate the psychometric properties of the HBS, CFA was conducted on the second portion of the dataset (n = 380) using Amos V.24. The Amos software was chosen because the covariance-based SEM allows for the assessment of an entire structural model via the fit statistics that compare the estimated covariance matrix to the observed covariance matrix ().

A model with four first-order factors was tested based on the EFA results. Correlations between factors were expected and allowed. The maximum likelihood estimation method was used as all variables were sufficiently normal based on the recommended criteria of the skewness and kurtosis values ().

The statistical accuracy of the model was estimated using absolute, incremental and parsimony fit indices. The proposed model exhibited a good model fit: χ2 (71) = 114.36; χ2/df = 1.61; GFI = 0.96; AGFI = 0.94; RMSEA = 0.04; SRMR = 0.03; NFI = 0.96; TLI = 0.98; CFI = 0.98; PNFI = 0.75 (; ).

Multiple approaches were used to assess the reliability and validity of the construct. The reliability was measured using Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR). The average variance extracted (AVE) was applied to assess the convergent validity. The Fornell–Larcker criterion and Heterotrait–Monotrait Ratio (HTMT) were applied to evaluate the discriminant validity (DV).

Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.840 to 0.881, whereas the CR statistics ranged from 0.844 to 0.881 (Table 7). Both indicators of reliability had values over the required threshold of 0.70 (). Hence, the construct reliability was established.

Table 7.

Construct reliability analysis.

The results of the construct validity analysis are presented in Table 8. The AVE of each latent variable was greater than the cut-off value of 0.5 and the square of the correlation coefficient of the constructs with other constructs (). All HTMT values were consistently smaller than the benchmark of 0.85 (), indicating once again no lack of discriminant validity (Table 9). Hence, the construct validity for the model was established.

Table 8.

Construct validity analysis.

Table 9.

Discriminant validity with HTMT.

Finally, the common method bias was tested using the common latent factor (CLF). The differences in the standardized regression weights of all items with and without CLF were found to be under 0.2, indicating that CMB was not a concern in this study ().

The final four-factor model with a path coefficient has been presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Four-factor model of HBS. Note: All coefficient values are standardized and they can be seen above the linked path. p < 0.05.

3.3. Study 3: Nomological Validity

We chose to assess the nomological validity of the developed HB scale with two relevant scales—materialism and sustainable purchase behavior (SPB)—for two main reasons. First, it was found that there were measurement scales for materialism, which was also regarded as unsustainable behavior (). Secondly, there are few studies to date that have investigated the influence of values with a negative effect, such as materialism or hyperconsumption, on sustainable-related behavior (; ).

In the consumer behavior literature, materialism is typically defined as “the importance consumers place on material goods as a means for reaching important life goals” (; ). Some authors contend that “everybody is to some extent materialistic“ (). We support this view, but in relation to hyperconsumption, we would like to stress that not every consumer may be regarded as a hyper-consumer. In addition, a materialistic lifestyle is dominated by a certain cultural worldview of individuals () and is connected with a desire for the possession of material goods, whereas hyperconsumption affects excess consumption in all domains of human life. Perhaps, materialistically oriented individuals would be more inclined to demonstrate behavior that tends towards hyperconsumption. We expect that materialism will positively affect all HB dimensions.

Sustainable purchasing involves procuring sustainable products that possess social, economic, and environmentally friendly attributes (). Considering the results of previous research (; ; ) that concern the impact of materialism on sustainability-related behavior, we assume that, similar to materialism, HB will also have a negative effect upon sustainable purchase behavior (SPB).

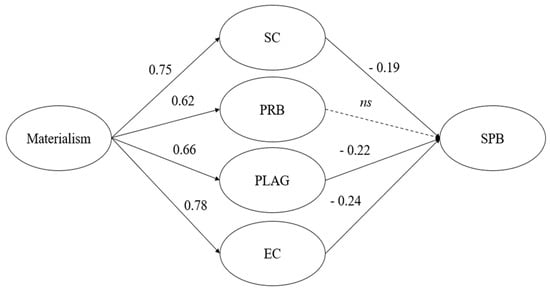

Hence, the nomological validity of the developed HB scale was assessed by testing its association with two relevant scales of materialism and SPB. Materialism was measured using a 9-item short version of the () scale as proposed and tested by (). The scale measuring SPB (4 items) was taken from (). For the purpose of the nomological validation, a sample of 273 respondents was collected. It was expected that materialism would be positively related with the HB scale, while HB would be negatively related with SPB. A structural equation model was assessed with AMOS and delivered an acceptable fit: χ2 (316) = 656.99; χ2/df = 2.08; GFI = 0.84; AGFI = 0.81; RMSEA = 0.06; SRMR = 0.05; NFI = 0.89; TLI = 0.93; CFI = 0.94; PNFI = 0.80. The results revealed that materialism positively affected all HB dimensions, which in turn had a negative impact on the SPB scale, except for the PRB dimension, which showed a non-significant relation with SPB (Figure 2). Therefore, the nomological validity of the scale was established.

Figure 2.

Results of the nomological analysis. Note: p < 0.05; ns: non-significant.

4. Discussion

Our objective was to develop and test a scale to measure hyperconsumption behavior in a valid and efficient way. To this end, a thorough literature review was completed, followed by three related studies. On the basis of the literature review, the conclusion was drawn that there was a growing body of research devoted to the scales that tended to measure “intention” or “attitude” to purchase rather than how consumers acted in reality. A similar finding was reported by (). In this sense, we found it more useful to examine actual occurrences of hyperconsumption rather than the propensity or attitude to this phenomenon. Initially, a qualitative study was conducted (2 focus group discussions with 10 participants in each FGD and 15 IDI), resulting in the generation of 34 items intended to measure HB. This initial scale was validated by discussion with 5 subject experts and 28 items remained after the content validation. The survey sample comprised 708 participants who were divided randomly into 2 sub-samples. The smaller sub-sample (n = 338) was analyzed using EFA, and the larger sub-sample (n = 370) was analyzed using CFA. After the EFA, the initial pool of 28 items was reduced to a final set of 14 items. The final measurement scale consisted of four interrelated HB factors, namely the following: shopping control (five items); perceived repair benefits (three items); possession of large amounts of goods (three items); and experiential consumption (three items).

The CFA results revealed a good model of fit of the refined scale, based on a number of absolute, incremental and parsimony fit indices.

Furthermore, this study confirmed the nomological validity of the model by demonstrating a positive effect of materialism on HB and a negative effect of HB on SCB.

5. Conclusions

This study is a first attempt at enabling the quantitative assessment of hyperconsumption behavior. Thus far, the majority of the authors of specialized literature have considered the manifestations of hyperconsumption by consumers on a predominantly conceptual level. In this regard, our research contributes to the existing literature by elaborating an HB conceptualization and a reliable and valid scale with the desirable psychometric properties. The new HB construct is a four-dimension, fourteen-item and seven-response-choice frequency scale of the first-order.

There are a few limitations to our research. Firstly, our scale does not measure intention or attitude; instead, it measures the physical manifestations of HB from a consumer’s point of view. Secondly, the scale provides an efficient method for assessing HB but does not allow for the examination of the effect of the specific psychological factors that shape or interfere with people’s consumption preferences, e.g., compensation, social motives, affective forecasting, adaptation, etc. (). Thirdly, as the sample in Study 2 reflects the population structure in a country of our choice, it does not ensure representativeness of the data. Nevertheless, we believe that these limitations do not undermine the value of our scale. In our opinion, the scale provides a valid and helpful instrument for future research in the field of hyperconsumption behavior.

We suggest that the situational contexts of consumers be included in future studies. For instance, the idea of the existence of a communist footprint affecting the current behavior of individuals may be used (). In this way, a better understanding can be achieved on the effect of the absence compared to the duration of exposition to communism (low or high level of communist footprint) on HB. Another research direction that could be of interest to future researchers in the field is the HB effect on sustainable consumption behavior as habits in all behavior categories: quality of life; caring for the environment and resources for future generations (). Another possibility for future research is to test the links between one construct and other constructs, such as brand addiction (), propensity to buy on credit (), willingness to participate (), etc. In addition, differences may be observed in the manifestations of hyperconsumption depending on sociodemographic factors, such as gender, age, income, etc.

The output of this research has essential implications for the public institutions, which play an important role in the development of a regulatory context and strategic orientation towards the adoption of sustainable consumption and production models for business enterprises, which will benefit from the manufacture of sustainable products; for non-governmental organizations, which can raise public awareness and culture regarding environmental issues; and for consumers, who are increasingly informed and could form more sustainable consumption habits.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.D. and V.S.; methodology, T.D.; software, I.I.; validation, T.D. and I.I.; formal analysis, I.I.; investigation, T.D.; resources, T.D.; writing—original draft preparation, T.D. and I.I.; writing—review and editing, T.D.; visualization, I.I.; supervision, T.D. and V.S.; project administration, T.D.; funding acquisition, T.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department for Scientific and Applied Activities at the University of Plovdiv Paisii Hilendarski, Bulgaria (Project ФП21-ФИCH-004).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the Guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the certified sociological agency BluePoint Ltd. The respondents confirmed their participation using a consent form.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Items generated from the qualitative study and purified based on content validity.

Table A1.

Items generated from the qualitative study and purified based on content validity.

| Factors and Preliminary Items | Source | Items Retained Based on Content Experts’ Suggestion |

|---|---|---|

| Shopping control (food) | ||

| SC1. I often buy food in packages that are too big for my household’s needs. | (; ) | Retained |

| SC2. I frequently buy too much food. | () | Retained |

| SC3. I frequently end up buying food that I did not intend to buy. | () | Retained |

| SC4. The layout of the products in supermarkets makes me purchase unnecessary items. | (; ) | Retained |

| SC5. Special offers in supermarkets make me buy more food than necessary. | (; ) | Retained |

| SC6. I find it difficult to plan my food shopping in such a way that all the food I purchase is eaten. | (; ) | Retained |

| SC7. I have the feeling that I cannot do anything about the food wasted in my household. | (; ) | Retained |

| Perceived repair benefits | Own development | |

| PRB1. I prefer to buy new electrical appliances rather than repair the old ones. | Retained | |

| PRB2. I prefer replacement to repair if a newly purchased item turns out to be faulty. | Retained | |

| PRB3. The repair of appliances is unnecessarily time-consuming. | Retained | |

| PRB4. I do not like mending my old clothes. | Retained | |

| PRB5. I remember the bitter experience I had last time I had my apartment redecorated. | Retained | |

| PRB6. I do not believe that repair saves me money. PRB7. I prefer to buy new shoes rather than repair old ones. | Retained Retained | |

| PRB8. I repair my home appliances myself. | Suggested to delete | |

| PRB9. I prefer to buy a new cell phone because I believe that repair services are of poor quality. | Retained | |

| Possession of large amounts of goods | Own development | |

| PLAG1. I have a lot of clothes that I have never worn. | Retained | |

| PLAG2. I have too many shoes that I do not wear. | Retained | |

| PLAG3. I have too many books that I will probably never read. | Retained | |

| PLAG4. I like having the latest electronic gadgets. | Retained | |

| PLAG5. I pride myself on the wide variety of accessories I possess. | Retained | |

| PLAG6. My child has so many toys that there is no room for them in my home. | Retained | |

| PLAG7. I have so many skincare products that I will not be able to use them before their expiry dates. | Retained | |

| PLAG8. I have different cars for commuting, intercity travel and off-road. | Suggested to delete | |

| Experiential consumption | Own development | |

| EC1. When I plan a journey abroad, I choose travelling by plane. | Retained | |

| EC2. I always choose excursions to different places. | Suggested to delete | |

| EC3. I feel the need for shared experiences of places and events. | Retained | |

| EC4. I want something exciting to happen at every moment of my life. | Retained | |

| EC5. I discover myself through constant communication with others. | Suggested to delete | |

| EC6. The work–home daily routine suffocates me. | Retained | |

| EC7. I do my best to make every family holiday an unforgettable memory. | Suggested to delete | |

| EC8. I frequently go to entertainment events (concerts, happenings and performances) that I am not a fan of. | Retained | |

| EC9. I go to all matches of my favorite football teams. | Retained | |

| EC10. I am addicted to video games. | Suggested to delete |

References

- Ackermann, Laura, Jan P. L. Schoormans, and Ruth Mugge. 2021. Measuring consumers’ product care tendency: Scale development and validation. Journal of Cleaner Production 295: 126327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Salinas, W., Sara Ojeda-Benitez, Samantha Cruz-Sotelo, and Juan R. Castro-Rodríguez. 2017. Model to evaluate pro-environmental consumer practices. Environments 4: 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahlström, Richard, Tommy Gärling, and John Thøgersen. 2020. Affluence and unsustainable consumption levels: The role of consumer credit. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption 1: 10003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albinsson, Pia A., Marco Wolf, and Dennis A. Kopf. 2010. Anti-consumption in East Germany: Consumer resistance to hyperconsumption. Journal of Consumer Behaviour 9: 412–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almanasreh, Enas, Rebekah Moles, and Timothy F. Chen. 2019. Evaluation of methods used for estimating content validity. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 15: 214–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzubaidi, Hawazin, Emma L. Slade, and Yogesh K. Dwivedi. 2021. Examining antecedents of consumers’ pro-environmental behaviours: TPB extended with materialism and innovativeness. Journal of Business Research 122: 685–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ammann, Jeanine, Olivia Osterwalder, Michael Siegrist, Christina Hartmann, and Aisha Egolf. 2021. Comparison of two measures for assessing the volume of food waste in Swiss households. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 166: 105295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelova, Mina, Teofana Dimitrova, and Daniela Pastarmadzhieva. 2021. The effects of globalization: Hyper consumption and environmental consumer behavior during the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Economics and Business Administration 9: 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aubert, Nicole. 2006. L’individu hypermoderne et ses pathologies [The hypermodern individual and their pathologies]. L’Information psychiatrique 82: 605–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banalieva, Elitsa R., Charlotte M. Karam, David A. Ralston, Detelin Elenkov, Irina Naoumova, Marina Dabic, Vojko Potocan, Arunas Starkus, Wade Danis, and Alan Wallace. 2017. Communist footprint and subordinate influence behavior in post-communist transition economies. Journal of World Business 52: 209–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beavers, Amy S., John W. Lounsbury, Jennifer K. Richards, Schuyler W. Huck, Gary J. Skolits, and Shelley L. Esquivel. 2013. Practical considerations for using exploratory factor analysis in educational research. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation 18: 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Colin. 2004. I shop therefore I know that I am: The metaphysical basis of modern consumerism. In Elusive Consumption. Edited by Karin M. Ekström and Helene Brembeck. London: Routledge, pp. 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Colin. 2015. The curse of the new: How the accelerating pursuit of the new is driving hyper-consumption. In Waste Management and Sustainable Consumption: Reflections on Consumer Waste. Edited by Karin Ekström. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 29–51. [Google Scholar]

- Caniëls, Marjolein C. J., Wim Lambrechts, Johannes Platje, Anna Motylska-Kuźma, and Bartosz Fortuński. 2021. 50 shades of green: Insights into personal values and worldviews as drivers of green purchasing intention, behaviour, and experience. Sustainability 13: 4140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, Patricia, and Luis S. R. Gomez. 2018. Trend research and fashion branding in the modern hyperconsumption society. ModaPalavra e-periódico 11: 208–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Sébastien. 2005–2006. De la postmodernité à l’hypermodernité [From postmodernity to hypermodernity]. Argument—Politique, Société et Histoire 8: 1. Available online: http://www.revueargument.ca/article/2005-10-01/332-de-la-postmodernite-a-lhypermodernite.html (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Charles, Sébastien. 2009. For a humanism amid hypermodernity: From a society of knowledge to a critical knowledge of society. Axiomathes 19: 389–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Child, Dennis. 2006. The Essentials of Factor Analysis, 3rd ed. London: Continuum International. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Scott A., James E. S. Higham, and Christina T. Cavaliere. 2011. Binge flying: Behavioural addiction and climate change. Annals of Tourism Research 38: 1070–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, Joel E. 2020. Applied Structural Equation Modeling Using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Cyr, Marie G. 2020. China: Hyper-Consumerism. Abstract Identity. Cuaderno 78: 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dash, Ganesh, and Justin Paul. 2021. CB-SEM vs PLS-SEM methods for research in social sciences and technology forecasting. Technological Forecasting and Social Change 173: 121092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dávid, L. 2009. Environmental impacts of events. In Event Management and Sustainability. Edited by Razaq Raj and James Musgrave. Cambridge: CABI, pp. 66–75. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Alexander, Mohammad Reza Habibi, and Michel Laroche. 2018. Materialism and the sharing economy: A cross-cultural study of American and Indian consumers. Journal of Business Research 82: 364–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Andrade, Pedro. 2021. Globalization of consumption, lifestyles and ‘viral society’. E-Revista de Estudos Interculturais-REI 9: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhandra, Tavleen K. 2019. Achieving triple dividend through mindfulness: More sustainable consumption, less unsustainable consumption and more life satisfaction. Ecological Economics 161: 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanesh, Ganga S. 2020. Who cares about organizational purpose and corporate social responsibility, and how can organizations adapt? A hypermodern perspective. Business Horizons 63: 585–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrova, Teofana, Iliana Ilieva, and Mina Angelova. 2022. Exploring Factors Affecting Sustainable Consumption Behaviour. Administrative Sciences 12: 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Paddy. 2002. The sustainability of “sustainable consumption”. Journal of Macromarketing 22: 170–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dürrschmidt, Jörg, and Graham Taylor. 2007. Globalization, Modernity and Social Change: Hotspots of Transition. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. 2021. EU Code of Conduct for Responsible Food Business and Marketing Practices. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/system/files/2021-06/f2f_sfpd_coc_final_en.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Fachbach, Ines, Gernot Lechner, and Marc Reimann. 2022. Drivers of the consumers’ intention to use repair services, repair networks and to self-repair. Journal of Cleaner Production 346: 130969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Featherstone, Mike. 2007. Consumer Culture and Postmodernism, 2nd ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, Vitor B., and João Varajão. 2010. Nutritional monitoring and advising information system for healthcare support. In Handbook of Research on Developments in e-Health and Telemedicine: Technological and Social Perspectives. Edited by Maria Manuela Cruz Cunha, António J. Tavares and Ricardo Simoes. Hershey: Medical Information Science Reference, pp. 636–51. [Google Scholar]

- Field, Andy. 2018. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics, 5th ed. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Freund, Peter, and George Martin. 2008. Fast cars/fast foods: Hyperconsumption and its health and environmental consequences. Social Theory & Health 6: 309–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuller, Christie M., Marcia J. Simmering, Guclu Atinc, Yasemin Atinc, and Barry J. Babin. 2016. Common methods variance detection in business research. Journal of Business Research 69: 3192–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, Alvaro C., Aimee Ambrose, Anna Hawkins, and Stephen Parkes. 2021. High consumption, an unsustainable habit that needs more attention. Energy Research & Social Science 80: 102241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godignon, Anne, and Jean-Louis Thiriet. 1994. The end of alienation? In New French Thought: Political Philosophy. Edited by M. Lilla. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 220–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottschalk, Simon. 2009. Hypermodern Consumption and Megalomania. Journal of Consumer Culture 9: 307–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán Rincón, Alfredo, Ruby Lorena Carrillo Barbosa, Ester Martín-Caro Álamo, and Belén Rodríguez-Cánovas. 2021. Sustainable consumption behaviour in Colombia: An exploratory analysis. Sustainability 13: 802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, Joseph F., Jr., William C. Black, Barry J. Babin, and Rolph E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed. Upper Saddle River: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Zhen. 2013. On the transformation of value orientation of commodity symbols: Some philosophical considerations on spiritual transformation of consumptive activities. In Values of Our Times: Contemporary Axiological Research in China. Edited by Deshun Li. Berlin: Springer, pp. 109–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, Daire, Joseph Coughlan, and Michael Mullen. 2008. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods 6: 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hüttel, Alexandra, Florence Ziesemer, Mathias Peyer, and Ingo Balderjahn. 2018. To purchase or not? Why consumers make economically (non-)sustainable consumption choices. Journal of Cleaner Production 174: 827–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İşcan, Erhan. 2020. The Impact of Collaborative Consumption on Sustainable Development. In Sharing Economy and the Impact of Collaborative Consumption. Hershey: IGI Global, pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger-Erben, Melanie, Vivian Frick, and Tamina Hipp. 2021. Why do users (not) repair their devices? A study of the predictors of repair practices. Journal of Cleaner Production 286: 125382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jantzen, Christian, James Fitchett, Per Østergaard, and Mikael Vetner. 2012. Just for fun? The emotional regime of experiential consumption. Marketing Theory 12: 137–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jigani, Adina-Iuliana, Camelia Delcea, and Corina Ioanăș. 2020. Consumers’ behavior in selective waste collection: A case study regarding the determinants from Romania. Sustainability 12: 6527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Yatish, and Zillur Rahman. 2019. Consumers’ sustainable purchase behaviour: Modeling the impact of psychological factors. Ecological Economics 159: 235–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jyrkinen, Maddy. 2016. McSexualization of bodies, sex and sexualities: Mainstreaming the commodification of gendered inequalities. In Prostitution, Harm and Gender Inequality. Theory, Research and Policy. Edited by Maddy Coy. London: Routledge, pp. 13–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Henry F. 1974. An index of factorial simplicity. Psychometrika 39: 31–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kakkar, Shiva, Anurag Dugar, and Rajneesh Gupta. 2022. Decoding the sustainable consumer: What yoga psychology tells us about self-control and impulsive buying? South Asian Journal of Business Studies 11: 276–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karraker, Meg W. 2013. Global Families, 2nd ed. Edited by Susan Ferguson. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Karremans, Johan C., Mathieu Kacha, Jean-Luc Herrmann, Christophe Vermeulen, and Olivier Corneille. 2016. Oversatiation negatively affects evaluation of goal-relevant (but not goal-irrelevant) advertised brands. Journal of Consumer Marketing 33: 354–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, Sushant, and Rambalak Yadav. 2021. The impact of shopping motivation on sustainable consumption: A study in the context of green apparel. Journal of Cleaner Production 295: 126239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lai, Michael K. W., and Amy P. Y. Ho. 2020. Unravelling potentials and limitations of sharing economy in reducing unnecessary consumption: A social science perspective. Resources, Conservation and Recycling 153: 104546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laitala, Kirsi, Ingun G. Klepp, Vilde Haugrønning, Harald Throne-Holst, and Pål Strandbakken. 2021. Increasing repair of household appliances, mobile phones and clothing: Experiences from consumers and the repair industry. Journal of Cleaner Production 282: 125349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Minh T. H. 2020. Social comparison effects on brand addiction: A mediating role of materialism. Heliyon 6: e05460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Weng M. 2017. Inside the sustainable consumption theoretical toolbox: Critical concepts for sustainability, consumption, and marketing. Journal of Business Research 78: 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindblom, Arto, Taru Lindblom, and Heidi Wechtler. 2018. Collaborative consumption as C2C trading: Analyzing the effects of materialism and price consciousness. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 44: 244–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2005. Time against time: Or the hypermodern society. In Hypermodern Times. Edited by Gilles Lipovetsky and Sébastien Charles. Malden: Polity Press, pp. 29–71. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2008. Paradoksalnoto shtastie: Opit varhu obshtestvoto na hiperkonsumirane [The Paradoxical Happiness: Essay on Hyperconsumption Society]. Sofia: Riva. [Google Scholar]

- Lipovetsky, Gilles. 2011. The hyperconsumption society. In Beyond the Consumption Bubble. Edited by Karin Ekström and Kay Glans. London: Routledge, pp. 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- Maden, Deniz, and Nahit E. Köker. 2013. An empirical research on consumer innovativeness in relation with hedonic consumption, social identity and self-esteem. Journal of Educational and Social Research 3: 569–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Matsunaga, Masaki. 2010. How to factor-analyze your data right: Do’s, don’ts, and how-to’s. International Journal of Psychological Research 3: 97–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mette, Frederike M. B., Celso Augusto de Matos, Simoni F. Rohden, and Mateus Canniatti Ponchio. 2019. Explanatory mechanisms of the decision to buy on credit: The role of materialism, impulsivity and financial knowledge. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance 21: 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, Li, Xinran Lehto, and Wei Wei. 2011. The Hedonic Experience of Travel-Related Consumption. International CHRIE Conference-Refereed Track. 7. Available online: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/refereed/ICHRIE_2011/Saturday/7 (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Migliore, Daniel L. 2014. Faith Seeking Understanding: An Introduction to Christian Theology, 3rd ed. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Forestry of Bulgaria. 2021. National Program to Prevent and Reduce Food Loss 2021–2026. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/food/safety/food_waste/eu-food-loss-waste-prevention-hub/eu-member-state-page/show/BG (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Ministry of Interior of the Republic of Bulgaria. 2020. Voluntary National Review of the Republic of Bulgaria of the Implementation of the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/26289VNR_2020_Bulgaria_Report.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Mondéjar-Jiménez, Juan-Antonio, Guido Ferrari, Luca Secondi, and Ludovica Principato. 2016. From the table to waste: An exploratory study on behaviour towards food waste of Spanish and Italian youths. Journal of Cleaner Production 138: 8–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niinimäki, Kirsi, Greg Peters, Helena Dahlbo, Patsy Perry, Timo Rissanen, and Alicon Gwilt. 2020. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment 1: 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunnally, Jim C., and Ira H. Bernstein. 1994. Psychometric Theory, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Pandelaere, Mario. 2016. Materialism and well-being: The role of consumption. Current Opinion in Psychology 10: 33–38. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1854/LU-8512528 (accessed on 4 November 2022). [CrossRef]

- Papadas, Karolos-Konstantinos, George J. Avlonitis, and Marylyn Carrigan. 2017. Green marketing orientation: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Journal of Business Research 80: 236–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pla Vargas, Lluís. 2014. Hiperconsumo y devaluación política [Hyperconsumption and political devaluation]. Oxímora Revista Internacional De Ética Y Política 5: 17–30. Available online: https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/oximora/article/view/10805 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Purcell, Rod. 2005. Working in the Community: Perspectives for Change, 2nd ed. Durham: Lulu Press. [Google Scholar]

- Qazi, Asim, Veronique Cova, Shahid Hussain, and Ubedullah Khoso. 2022. When and why consumers choose supersized food? Spanish Journal of Marketing–ESIC 26: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quoquab, Farzana, Jilhad Mohammad, and Nurain N. Sukari. 2019. A multiple-item scale for measuring “sustainable consumption behaviour” construct: Development and psychometric evaluation. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 31: 791–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhéaume, Jacques. 2017. Subject and hypermodernity. Psicología, Conocimiento y Sociedad 6: 223–42. Available online: http://www.scielo.edu.uy/pdf/pcs/v6n2/v6n2a12.pdf (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Richins, Marsha L. 2004. The material values scale: Measurement properties and development of a short form. Journal of Consumer Research 31: 209–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha L., and Lan Nguyen Chaplin. 2015. Material Parenting: How the Use of Goods in Parenting Fosters Materialism in the Next Generation. Journal of Consumer Research 41: 1333–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, Marsha L., and Scott Dawson. 1992. A consumer values orientation for materialism and its measurement: Scale development and validation. Journal of Consumer Research 19: 303–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritzer, George. 2012. “Hyperconsumption” and “hyperdebt”: A “hypercritical” analysis. In A debtor world. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Debt. Edited by Ralph Brubaker, Robert Lawless and Charles Tabb. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 60–86. [Google Scholar]

- Roult, Romain, and Frédéric Martineau. 2021. Flowart, a physical activity at the level of hypermodernity, even hypomodernity. Exercise and Quality of Life 13: 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandberg, Maria. 2021. Sufficiency transitions: A review of consumption changes for environmental sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production 293: 126097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seegebarth, Barbara, Mathias Peyer, Ingo Balderjahn, and Klaus-Peter Wiedmann. 2016. The sustainability roots of anti-consumption lifestyles and initial insights regarding their effects on consumers’ well-being. The Journal of Consumer Affairs 50: 68–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano Archimi, Carolina, Emmanuelle Reynaud, Hina M. Yasin, and Zeeshan A. Bhatti. 2018. How perceived corporate social responsibility affects employee cynicism: The mediating role of organizational trust. Journal of Business Ethics 151: 907–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. Joseph. 2001. Handbook of Quality-of-Life Research: An Ethical Marketing Perspective. Dordrecht: Springer Science+Business Media. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonego, Monique, Márcia E. Echeveste, and Henrique G. Debarba. 2022. Repair of electronic products: Consumer practices and institutional initiatives. Sustainable Production and Consumption 30: 556–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stancu, Violeta, Pernille Haugaard, and Liisa Lähteenmäki. 2016. Determinants of consumer food waste behaviour: Two routes to food waste. Appetite 96: 7–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stefan, Violeta, Erica van Herpen, Ana A. Tudoran, and Liisa Lähteenmäki. 2013. Avoiding food waste by Romanian consumers: The importance of planning and shopping routines. Food Quality and Preference 28: 375–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudbury Riley, Lynn, Florian Kohlbacher, and Agnes Hofmeister. 2014. A cross-cultural analysis of pro-environmental consumer behaviour among seniors. In Contemporary Issues in Green and Ethical Marketing. Edited by Morven McEachern and Marylyn Carrigan. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 100–121. [Google Scholar]

- Svensson-Hoglund, Sahra, Jessika L. Richter, Eléonore Maitre-Ekern, Jennifer D. Russell, Taina Pihlajarinne, and Carl Dalhammar. 2021. Barriers, enablers and market governance: A review of the policy landscape for repair of consumer electronics in the EU and the US. Journal of Cleaner Production 288: 125488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terzioğlu, Nazli. 2021. Repair motivation and barriers model: Investigating user perspectives related to product repair towards a circular economy. Journal of Cleaner Production 289: 125644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomșa, Monica-Maria, Andreea-Ioana Romonți-Maniu, and Mircea-Andrei Scridon. 2021. Is sustainable consumption translated into ethical consumer behavior? Sustainability 13: 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urien, Bertrand, and William Kilbourne. 2008. On the role of materialism in the relationship between death anxiety and quality of life. Advances in Consumer Research 35: 409–15. Available online: http://www.acrwebsite.org/volumes/13132/volumes/v35/NA-35 (accessed on 1 November 2022).

- Uzir, Md U. H., Hussam Al Halbusi, Rodney Lim, Ishraq Jerin, Abu B. A. Hamid, Thurasamy Ramayah, and Ahasanul Haque. 2021. Applied Artificial Intelligence and user satisfaction: Smartwatch usage for healthcare in Bangladesh during COVID-19. Technology in Society 67: 101780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeven, Piet, and Dejan Verčič. 2017. Organising and communicating in hypermodern times. Communication Director 4: 38–41. Available online: https://www.communication-director.com/issues/strategy-and-cco/organising-and-communicating-hypermodern-times/#.YjHc_zWxVPY (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Verhoeven, Piet, Ansgar Zerfass, Dejan Verčič, Ralph Tench, and Angeles Moreno. 2018. Public relations and the rise of hypermodern values: Exploring the profession in Europe. Public Relations Review 44: 471–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschers, Vivianne H. M., Nadine Wickli, and Michael Siegrist. 2016. Sorting out food waste behaviour: A survey on the motivators and barriers of self-reported amounts of food waste in households. Journal of Environmental Psychology 45: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voorhees, Clay M., Michael K. Brady, Roger Calantone, and Edward Ramirez. 2016. Discriminant validity testing in marketing: An analysis, causes for concern, and proposed remedies. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 44: 119–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Luxiao, Dian Gu, Jiang Jiang, and Ying Sun. 2019. The Not-So-Dark Side of Materialism: Can Public Versus Private Contexts Make Materialists Less Eco-Unfriendly? Frontiers in Psychology 10: 790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- West, Stephen G., John F. Finch, and Patrick J. Curran. 1995. Structural equation models with nonnormal variables: Problems and remedies. In Structural Equation Modeling: Concepts, Issues, and Applications. Edited by Rick Hoyle. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, pp. 56–75. [Google Scholar]

- Xiaohong, Zhou. 2020. Cultural Reverse II: The Multidimensional Motivation and Social Impact of Intergenerational Revolution. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Yuwei, Gao, Yuan Chen, Yangguang Zhu, and Shaofu Du. 2022. Pricing design and contract selection with customers’ self-control: A strategic analysis. Journal of Modelling in Management. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaman, Atiq U., and Steffen Lehmann. 2013. The zero waste index: A performance measurement tool for waste management systems in a ‘zero waste city’. Journal of Cleaner Production 50: 123–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).