Child Citizenship Status in Immigrant Families and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Parental Time Investments in Children

1.2. Parental Time Investments in Children with and without Citizenship Status

1.3. Research Questions

- How does overall time with parents, one-on-one time with parents, and quality time with parents vary for children in immigrant families in mixed-citizenship status sibships versus those in same-citizenship status sibships (i.e., all citizens and all non-citizens)?

- Which child, parent, and household factors best account for the observed differences in parental time investments by children’s citizenship sibship type (mixed-status versus same-status)?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Primary Explanatory Variable: Citizenship Status of a Child

2.2.2. Dependent Variables: Parental Time Investments

2.2.3. Control Variables

2.3. Analytical Approach

3. Results

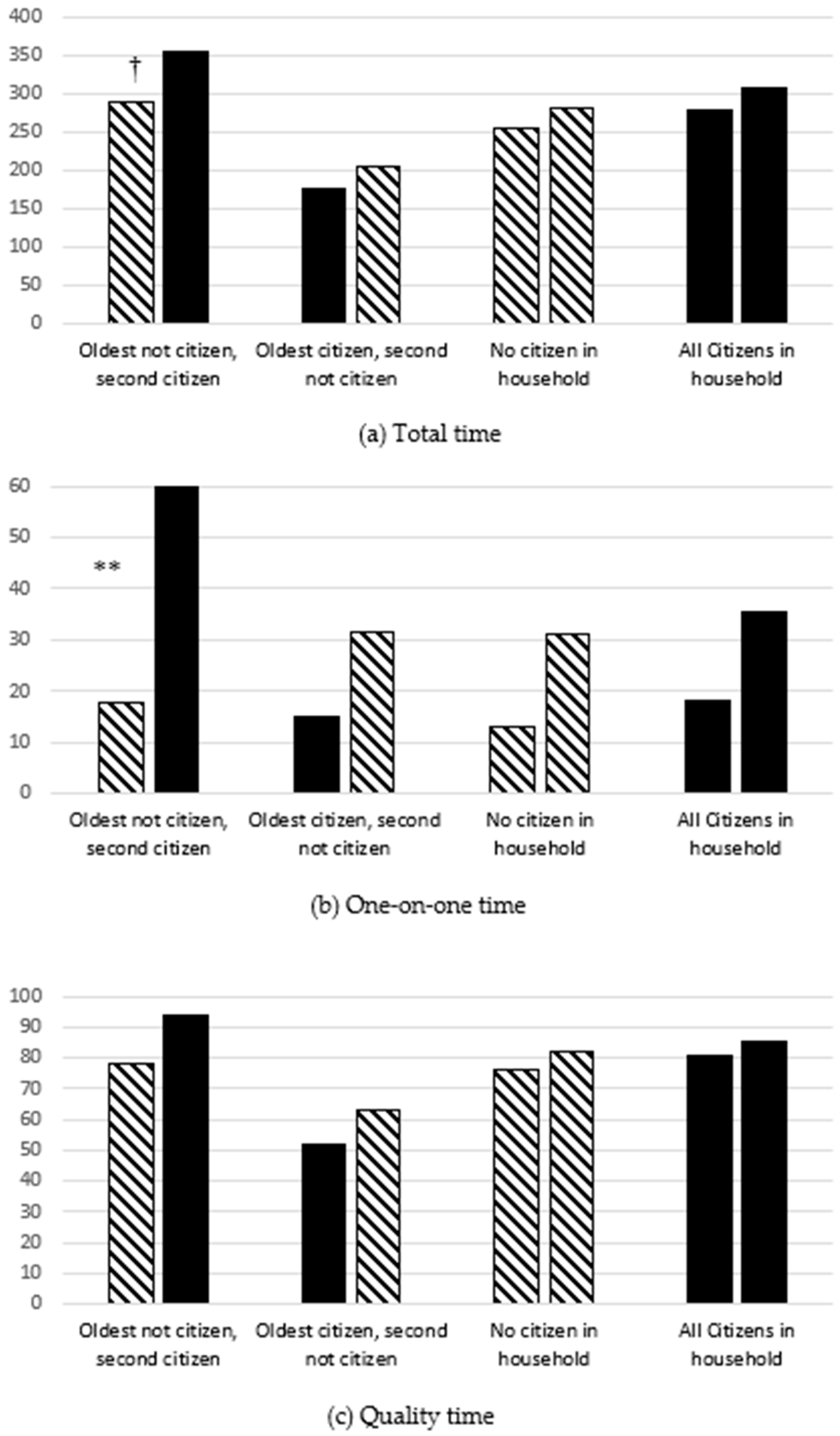

3.1. Descriptive Results

3.2. Multivariate Model Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Activity Description | ATUS Activity Codes | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Time | Any time the parent spends with the focal child | All activity codes |

| One-on-one Time | Any time the parent spends with only the focal child and no other people | All activity codes |

| Quality Time | Activities carried out with the focal child including reading, arts and crafts, playing sports, exercise, talking with or listening to, homework or home schooling, providing medical care to, eating and drinking, playing games, hobbies, attending museums and performing arts, religious services, and religious activities | 30102-30106, 30201, 30203, 30301, 110101, 110199, 110201, 110299, 119999, 120307, 120309-120313, 120401, 120402, 130101-130136, 130199, 140101-140102, 149999 |

| Total Time | One-on-One Time | Quality Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | |

| Citizenship | ||||||

| Has citizenship, sibling does not | 0.22 | 13.37 | 0.68 | 6.31 | 3.05 | 5.35 |

| Has no citizenship, sibling does | −12.09 | 13.19 | −4.44 | 3.12 | −3.45 | 4.89 |

| No citizenship, self or siblings | 0.96 | 12.23 | −0.21 | 3.31 | 4.21 | 5.01 |

| Citizenship, self and sibs | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female | 1.04 | 3.40 | −0.45 | 2.63 | −0.04 | 1.05 |

| Age | −9.64 *** | 1.33 | −7.08 *** | 1.10 | −1.91 *** | 0.44 |

| Birth order | ||||||

| Oldest (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youngest | −7.20 | 4.72 | −8.30 * | 3.80 | −1.71 | 1.62 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | −32.50 * | 13.72 | 2.15 | 3.97 | −27.87 *** | 5.36 |

| Hispanic | 3.53 | 8.35 | 2.32 | 2.40 | −9.36 ** | 3.54 |

| Other (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female responding parent | 58.67 *** | 7.25 | 13.16 *** | 2.02 | 7.41 * | 3.37 |

| Married responding parent | 33.80 ** | 11.03 | −6.54 | 3.55 | 16.44 *** | 4.51 |

| Age of responding parent | −1.33 * | 0.56 | 0.13 | 0.17 | −0.09 | 0.26 |

| Responding parent is an immigrant | 14.29 | 8.51 | 0.53 | 2.33 | 13.50 *** | 3.59 |

| Responding parent is not English language proficient | 10.52 | 10.06 | −2.22 | 2.90 | −1.75 | 4.40 |

| Highest education of responding parent | ||||||

| Less than High School | 8.38 | 10.60 | −5.11 | 2.88 | −7.69 | 4.90 |

| High School | −14.37 | 9.02 | −3.34 | 2.48 | −8.43 * | 3.58 |

| Some College + (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Responding parent worked full time | −119.47 *** | 8.18 | −22.82 *** | 2.66 | −33.81 *** | 3.98 |

| Yearly family incomea | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 *** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Average age of household children | −2.71 | 1.60 | 6.43 *** | 1.14 | −2.76 *** | 0.59 |

| Std. dev. of age of household children | −0.64 | 1.79 | 6.31 *** | 0.73 | −1.33 | 0.84 |

| Fraction female of household children | 13.09 | 9.72 | 4.64 | 3.60 | −4.07 | 4.70 |

| Mean | 292.54 | 27.25 | 82.82 | |||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.09 | |||

| Unadjusted Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A—Has Citizenship, Sibling Does Not | Group B—No Citizenship, Sibling Has Citizenship | Group C—No Children in Household Have Citizenship | Group D—All Children in Household Have Citizenship | |

| N = 1669 | N = 1491 | N = 1641 | N = 20,923 | |

| Total time | 339.02 bcd | 293.49 a | 276.47 ad | 297.28 ac |

| One-on-one time | 31.96 bcd | 14.25 acd | 21.88 ab | 21.79 ab |

| Quality time | 90.42 bcd | 79.00 a | 83.03 a | 82.27 a |

| Adjusted Results | ||||

| Total time | 305.23 | 296.63 | 304.24 | 297.28 |

| One-on-one time | 30.8 | 22.57 | 25.66 | 21.79 |

| Quality time | 88.26 | 84.64 | 91.88 | 82.27 |

| 1 | The ATUS classified household children of a coresident partner as children of the respondent about half of the time, and foster children were not classified as children of the respondent. |

| 2 | Children in households with missing information on child citizenship differed in terms of individual and household characteristics. They were younger, had younger parents, had more educated parents, had higher household incomes, and had fewer children in the family compared to those providing citizenship information. They were also more likely to be missing information on race and ethnicity. |

References

- Abrego, Leisy. 2019. Sacrificing Families: Navigating Labor, Laws, and Love across Borders. Stanford: Stanford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Aguiar, Mark, and Eric Hurst. 2007. Measuring trends in leisure: The allocation of time over five decades. Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 969–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, and Chad Sparber. 2014. In-State Tuition for Undocumented Immigrants and Its Impact on College Enrollment, Tuition Costs, Student Financial Aid, and Indebtedness. Regional Science and Urban Economics 49: 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Amuedo-Dorantes, Catalina, and Francisca Antman. 2017. Schooling and Labor Market Effects of Temporary Authorization: Evidence from DACA. Journal of Population Economics 30: 339–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attanasio, Orazio, Sarah Cattan, Emla Fitzsimons, Costas Meghir, and Marta Rubio-Codina. 2020. Estimating the production function for human capital: Results from a randomized controlled trial in Colombia. American Economic Review 110: 48–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Michael, and Kevin Milligan. 2016. Boy-girl differences in parental time investments: Evidence from three countries. Journal of Human Capital 10: 399–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, Gary, and Nigel Tomes. 1976. Child endowments and the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy 84: 143–62. [Google Scholar]

- Behrman, Jere R., Mark R. Rosenzweig, and Paul Taubman. 1994. Endowments and the allocation of schooling in the family and in the marriage market: The twin experiment. Journal of Political Economy 102: 1131–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger Cardoso, Jodi, Kalina Brabeck, Randy Capps, Tzuan Chen, Natalia Giraldo-Santiago, Anjely Huertas, and Nubia A. Mayorga. 2021. Immigration enforcement fear and anxiety in Latinx high school students. Journal of Adolescent Health 68: 961–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blake, Judith. 1981. Family size and the quality of children. Demography 18: 421–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozick, Robert, and Trey Miller. 2014. In-State College Tuition Policies for Undocumented Immigrants: Implications for High School Enrollment among Non-Citizen Mexican Youth. Population Research and Policy Review 33: 13–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozick, Robert, Trey Miller, and Matheu Kaneshiro. 2016. Non-Citizen Mexican Youth in US Higher Education: A Closer Look at the Relationship between State Tuition Policies and College Enrollment. International Migration Review 50: 864–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breining, Sanni, Joseph Doyle, David N. Figlio, Krzysztof Karbownik, and Jeffrey Roth. 2020. Birth Order and Delinquency: Evidence from Denmark and Florida. Journal of Labor Economics 38: 95–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2019. American Time Use Survey user’s guide: Understanding ATUS 2003 to 2018. Available online: https://www.atusdata.org/atus/resources/linked_docs/atususersguide.pdf (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Castañeda, Heide, and Milena Andrea Melo. 2014. Health Care Access for Latino Mixed-Status Families: Barriers, Strategies, and Implications for Reform. American Behavioral Scientist 58: 1891–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catron, Peter. 2019. The citizenship advantage: Immigrant socioeconomic attainment in the age of mass migration. American Journal of Sociology 124: 999–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cha, Yun, and Hyunjoon Park. 2020. Converging educational differences in parents’ time use in developmental child care. Journal of Marriage and Family 83: 769–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Eleanor Jawon, and Jisoo Hwang. 2015. Child gender and parental inputs: No more son preference in Korea? American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 105: 638–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobb-Clark, Deborah, Nicolas Salamanca, and Anna Zhu. 2019. Parenting style as an investment in human development. Journal of Population Economics 32: 1315–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, Ann C., and M. Sue Crowley. 1990. School-age children’s time alone with fathers in single- and dual-earner families: Implications for the father-child relationship. Journal of Early Adolescence 10: 296–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crouter, Ann C., Melissa R. Head, and Susan M. McHale. 2004. Family time and the psychosocial adjustment of adolescent siblings and their parents. Journal of Marriage and Family 66: 147–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, Janet, and Doug Almond. 2011. Human capital development before age five. In Handbook of Labor Economics. Edited by Orley Ashenfelter and David Card. Oxford: Elsevier, vol. 4B, pp. 1315–486. [Google Scholar]

- Del Boca, Daniela, Christopher Flinn, and Matthew Wiswall. 2014. Household choices and child development. The Review of Economic Studies 81: 137–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bono, Emilia, Marco Francesconi, Yvonne Kelly, and Amanda Sacker. 2016. Early Maternal Time Investments and Early Child Outcomes. The Economic Journal 126: F96–F135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickson, Lisa M., T. H. Gindling, and James Kitchin. 2017. The Education and Employment Effects of DACA, in-State Tuition and Financial Aid for Undocumented Immigrants. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 11,109. Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics. Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/11109/the-education-and-employment-effects-of-daca-in-state-tuition-and-financial-aid-for-undocumented-immigrants (accessed on 29 October 2022).

- Dreby, Joanna. 2015. Everyday Illegal. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dreby, Joanna, Florencia Silveira, and Eunju Lee. 2022. The anatomy of immigration enforcement: Long-standing socio-emotional impacts on children as they age into adulthood. Journal of Marriage and Family 84: 713–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enriquez, Laura E. 2015. Multigenerational Punishment: Shared Experiences of Undocumented Immigration Status Within Mixed-Status Families. Journal of Marriage and Family 77: 939–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiorini, Mario, and Michael Keane. 2014. How the allocation of children’s time affects cognitive and noncognitive development. Journal of Labor Economics 32: 787–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomby, Paula, and Kelly Musick. 2018. Mothers’ time, the parenting package, and links to healthy child development. Journal of Marriage and Family 80: 166–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertler, Paul, James Heckman, Rodrigo Pinto, Arianna Zanolini, Christel Vermeersch, Susan Walker, Susan M. Chang, and Sally Grantham-McGregor. 2014. Labor market returns to an early childhood stimulation intervention in Jamaica. Science 344: 998–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibby, Ashley Larsen, Jocelyn S. Wikle, and Kevin Thomas. 2021. Adoption Status and Parental Investments: A Within-Sibling Approach. Journal of Child and Family Studies 30: 1776–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Roberto G. 2009. On the rights of undocumented children. Society 46: 419–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzales, Roberto G. 2011. Learning to be illegal undocumented youth and shifting legal contexts in the transition to adulthood. American Sociological Review 76: 602–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, Eric D., Avi Simhon, and Bruce A. Weinberg. 2019. Does parent quality matter? Evidence on the transmission of human capital using variation in parental influence from death, divorce, and family size. Journal of Labor Economics 38: 569–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossbard, Shoshana Amyra, and Victoria Vernon. 2020. Do immigrants pay a price when marrying natives? Lessons from the US time use survey. IZA Journal of Development and Migration 11: 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gugl, Elisabeth, and Linda Welling. 2012. Time with sons and daughters. Review of Economics of the Household 10: 277–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guryan, Jonathan, Erik Hurst, and Melissa Kearney. 2008. Parent education and parental time with children. Journal of Economics Perspectives 22: 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Erin R., Caitlin Patler, and Robin Savinar. 2021. Transition into Liminal Legality: DACA’s Mixed Impacts on Education and Employment among Young Adult Immigrants in California. Social Problems 68: 675–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofferth, Sandra L., Sarah M. Flood, Matthew Sobek, and Daniel Backman. 2020. American Time Use Survey Data Extract Builder: Version 2.8 [Dataset]. College Park: University of Maryland. Minneapolis: IPUMS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jewers, Mariellen, and Leighton Ku. 2021. Noncitizen children face higher health harms compared with their siblings who have US citizen status. Health Affairs 40: 1084–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahneman, Daniel, Alan B. Krueger, David A. Schkade, Norbert Schwarz, and Arthur A. Stone. 2004. A survey method for characterizing daily life experience: The day reconstruction method. Science (New York, N.Y.) 306: 1776–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalil, Ariel, Rebecca Ryan, and Michael Corey. 2012. Diverging destinies: Maternal education and the developmental gradient in time with children. Demography 49: 1361–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaushal, Neeraj. 2008. In-State Tuition for the Undocumented: Education Effects on Mexican Young Adults. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 27: 771–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keown, Louise J., and Melanie Palmer. 2014. Comparisons between paternal and maternal involvement with sons: Early to middle childhood. Early Child Development and Care 184: 99–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimmel, Jean, and Rachel Connelly. 2007. Mothers’ time choices: Caregiving, leisure, home production, and paid work. Journal of Human Resources 42: 643–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowal, Amanda K., Jennifer L. Krull, and Laurie Kramer. 2006. Shared understanding of parental differential treatment in families. Social Development 15: 276–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuka, Elira, Na’ama Shenhav, and Kevin Shih. 2020. Do Human Capital Decisions Respond to the Returns to Education? Evidence from DACA. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 12: 293–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lam, Chun Bun, Susan M. McHale, and Ann C. Crouter. 2012. Parent-child shared time from middle childhood to late adolescence: Developmental course and adjustment correlates. Child Development 83: 2089–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, Reed W., and Maryse H. Richards. 1991. Daily companionship in late childhood and early adolescence: Changing developmental contexts. Child Development 62: 284–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larson, Reed W., Maryse H. Richards, Giovanni Moneta, Grayson Holmbeck, and Elena Duckett. 1996. Changes in adolescents’ daily interactions with their families from ages 10 to 18: Disengagement and transformation. Developmental Psychology 32: 744–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, Shelly, and Sabrina Wulff Pabilonia. 2007. Time Allocation of Parents and Investments in Sons and Daughters. Working Paper. ResearchGate. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/252401196_Time_Allocation_of_Parents_and_Investments_in_Sons_and_Daughters (accessed on 31 August 2020).

- Mammen, Kristin. 2011. Fathers’ time investments in children: Do sons get more? Journal of Population Economics 24: 839–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangual Figueroa, Ariana. 2012. “I have papers so I can go anywhere!”: Everyday talk about citizenship in a mixed-status Mexican family. Journal of Language, Identity and Education 11: 291–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milkie, Melissa A., Kei M. Nomaguchi, and Kathleen E. Denny. 2015. Does the amount of time mothers spend with children or adolescents matter? Journal of Marriage and Family 77: 355–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moroni, Gloria, Cheti Nicoletti, and Emma Tominey. 2019. Child Socio-Emotional Skills: The Role of Parental Inputs. IZA Discussion Paper, No. 12432. Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics. Available online: https://www.iza.org/publications/dp/12432/child-socio-emotional-skills-the-role-of-parental-inputs (accessed on 4 June 2020).

- Nottmeyer, Olga. 2014. Relative labor supply in intermarriage. IZA Journal of Migration 3: 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Offer, Shira. 2013. Family time activities and adolescents’ emotional well-being. Journal of Marriage and Family 75: 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passel, Jeffrey S. 2011. Demography of immigrant youth: Past, present, and future. The Future of Children 21: 19–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pope, Nolan G. 2016. The Effects of DACAmentation: The Impact of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals on Unauthorized Immigrants. Journal of Public Economics 143: 98–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Potochnick, Stephanie. 2014. How States Can Reduce the Dropout Rate for Undocumented Immigrant Youth: The Effects of in-State Resident Tuition Policies. Social Science Research 45: 18–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Price, Joseph. 2008. Parent-child quality time: Does birth order matter? Journal of Human Resources 43: 240–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price, Joseph, and Ariel Kalil. 2019. The effect of mother-child reading time on children’s reading skills: Evidence from natural within-family variation. Child Development 90: e688–e702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero Morales, Ana, and Andres J. Consoli. 2020. Mexican/Mexican-American siblings: The impact of undocumented status on the family, the sibling relationship, and the self. Journal of Latinx Psychology 8: 112–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosales-Rueda, Maria Fernanda. 2014. Family investment responses to childhood health conditions: Intrafamily allocation of resources. Journal of Health Economics 37: 41–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayer, Liana C., Suzanne M. Bianchi, and John P. Robinson. 2004. Are parents investing less in children? Trends in mothers’ and fathers’ time with children. American Journal of Sociology 110: 1–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, Lawrence. 2020. Adolescence, 12th ed. New York: McGraw Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Jay. 2013. Tobit or not Tobit? Journal of Economic and Social Measurement 38: 263–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, Michael. 2013. Resilience, trauma, context, and culture. Trauma, Violence and Abuse 14: 255–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ungar, Michael, Mehdi Ghazinour, and Jorg Richter. 2013. Annual research review: What is resilience within the social ecology of human development? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 54: 348–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hook, Jennifer, and Kelly Stamper Balistreri. 2006. Ineligible parents, eligible children: Food stamps receipt, allotments, and food insecurity among children of immigrants. Social Science Research 35: 228–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vargas, Andres J., and Manuel Chavez. 2010. Assimilation Effects beyond the Labor Market: Time Allocation of Mexican Immigrants to the U.S. Lubbock: Texas Tech University. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, Edward D., and Vickie D. Ybarra. 2017. U.S. Citizen Children of Undocumented Parents: The Link between State Immigration Policy and the Health of Latino Children. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19: 913–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wikle, Jocelyn S., and Alexander C. Jensen. 2021. Childhood Disabilities and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings. Paper presented at European Society for Population Economics Meeting, Virtual, June 18. [Google Scholar]

- Wikle, Jocelyn S., and Clara Wilson. 2021. Parental Time Investments in Children through Childhood. Paper presented at Population Association of America Annual Meetings, Virtual, May 6. [Google Scholar]

- Wikle, Jocelyn S., Elizabeth Ackert, and Alexander C. Jensen. 2019. Companionship patterns and emotional states during social interactions for adolescents with and without siblings. Journal of Youth and Adolescence 48: 2190–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Qingwen, and Kalina Brabeck. 2012. Service utilization for Latino children in mixed-status families. Social Work Research 36: 209–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshikawa, Hirokazu, and Ariel Kalil. 2011. The effects of parental undocumented status on the developmental contexts of young children in immigrant families. Child Development Perspectives 5: 291–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zayas, Luis H., and Lauren E. Gulbas. 2017. Processes of belonging for citizen-children of undocumented Mexican immigrants. Journal of Child and Family Studies 26: 2463–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Group A—Has Citizenship, Sibling Does Not | Group B—No Citizenship, Sibling Has Citizenship | Group C—No Children in Household Have Citizenship | Group D—All Children in Household Have Citizenship | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 533 | N = 533 | N = 902 | N = 11,044 | |

| Characteristics of the Focal Child | ||||

| Age | 5.59 bcd | 11.10 ad | 11.01 ad | 8.35 abc |

| Female | 0.51 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| Black non-Hispanic | 0.09 c | 0.09 c | 0.06 ab | 0.07 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.13 d | 0.10 d | 0.14 d | 0.21 abc |

| Hispanic | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| Oldest household child | 0.07 bcd | 0.93 acd | 0.50 ab | 0.50 ab |

| Youngest household child | 0.93 bcd | 0.07 acd | 0.50 ab | 0.50 ab |

| Characteristics of the Focal Parent | ||||

| Parent is female | 0.53 | 0.53 | 0.54 | 0.53 |

| Parent is married | 0.91 d | 0.91 d | 0.91 d | 0.87 abc |

| Age of parent | 37.64 cd | 37.64 cd | 39.93 abd | 38.99 abc |

| Parent is an immigrant | 0.98 d | 0.98 d | 0.98 d | 0.84 abc |

| Highest education of parent | ||||

| Less than High School | 0.29 d | 0.29 d | 0.30 d | 0.24 abc |

| High School | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.21 d | 0.25 c |

| Some College + | 0.46 d | 0.46 d | 0.49 | 0.51 ab |

| Works full-time | 0.62 cd | 0.62 cd | 0.69 ab | 0.71 ab |

| Characteristics of the Household | ||||

| Yearly family income | 61,428.05 d | 61,428.05 d | 63,534.76 d | 77,104.60 abc |

| Average age of household children | 8.35 c | 8.35 c | 11.01 abd | 8.35 abd |

| Std. dev. of age of household children | 4.25 cd | 4.25 cd | 2.68 ab | 2.62 ab |

| Fraction female of household children | 0.48 | 0.48 | 0.47 | 0.49 |

| Unadjusted Results | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A—Has Citizenship, Sibling Does Not | Group B—No Citizenship, Sibling Has Citizenship | Group C—No Children in Household Have Citizenship | Group D—All Children in Household Have Citizenship | |

| N = 533 | N = 533 | N = 902 | N = 11,044 | |

| Total time | 342.97 bcd | 284.87 a | 268.74 ad | 292.52 ac |

| One-on-one time | 56.38 bcd | 18.88 ad | 22.10 a | 26.70 ab |

| Quality time | 91.13 bc | 77.26 a | 79.28 a | 82.99 |

| Adjusted Results | ||||

| Total time | 300.62 | 290.22 | 289.76 | 292.52 |

| One-on-one time | 30.45 | 23.75 | 25.74 | 26.70 |

| Quality time | 85.01 | 80.66 | 88.61 | 82.99 |

| Total Time | One-on-One Time | Quality Time | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | β | SE(β) | |

| Citizenship | ||||||

| Has citizenship, sibling does not | 8.10 | 11.89 | 3.75 | 5.72 | 2.02 | 4.65 |

| Has no citizenship, sibling does | −2.30 | 11.64 | −2.95 | 2.77 | −2.33 | 4.25 |

| No citizenship, self or siblings | −2.76 | 10.82 | −0.96 | 2.84 | 5.62 | 4.37 |

| Citizenship, self and sibs (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female | 1.09 | 3.08 | −0.61 | 2.31 | −0.27 | 0.93 |

| Age | −9.79 *** | 1.18 | −6.79 *** | 0.97 | −2.00 *** | 0.39 |

| Birth order | ||||||

| Oldest (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Youngest | −7.28 | 4.26 | −7.76 * | 3.34 | −1.94 | 1.44 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||

| Black, non-Hispanic | −33.85 ** | 12.76 | 1.59 | 3.65 | −27.34 *** | 4.87 |

| Hispanic | 5.11 | 7.24 | 0.94 | 1.91 | −11.01 *** | 3.08 |

| Other (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Female responding parent | 59.66 *** | 6.61 | 13.43 *** | 1.79 | 7.89 ** | 3.00 |

| Married responding parent | 30.51 ** | 10.14 | −5.77 | 3.19 | 14.29 *** | 4.00 |

| Age of responding parent | −1.40 ** | 0.52 | 0.12 | 0.15 | −0.12 | 0.23 |

| Responding parent is an immigrant | 16.61 * | 7.70 | 0.65 | 2.02 | 11.78 *** | 3.29 |

| Highest education of responding parent | ||||||

| Less than High School | 10.99 | 9.19 | −5.72 * | 2.56 | −9.10 * | 4.40 |

| High School | −10.76 | 8.16 | −3.59 | 2.20 | −8.09 * | 3.19 |

| Some College + (reference) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Responding parent worked full time | −120.20 *** | 7.49 | −22.39 *** | 2.36 | −34.41 *** | 3.48 |

| Yearly family incomea | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 *** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Average age of household children | −2.92 * | 1.44 | 6.18 *** | 1.00 | −2.43 *** | 0.53 |

| Std. dev. of age of household children | −0.33 | 1.60 | 6.21 *** | 0.65 | −1.35 | 0.72 |

| Fraction female of household children | 11.38 | 8.88 | 3.87 | 3.21 | −1.86 | 4.25 |

| Mean | 292.54 | 27.25 | 82.82 | |||

| R2 | 0.18 | 0.06 | 0.09 | |||

| Total Time | One-on-One Time | Quality Time | |

|---|---|---|---|

| β | β | β | |

| Has citizenship | 2.85 | −3.23 | 3.79 |

| (9.83) | (4.57) | (3.53) | |

| Female | 13.03 | 2.47 | 2.05 |

| (6.57) | (3.64) | (2.09) | |

| Age | −8.22 *** | −2.58 *** | −1.33 ** |

| (1.49) | (0.77) | (0.50) | |

| Birth order | |||

| Oldest (reference) | -- | -- | -- |

| Middle | −22.80 * | −11.22 * | −1.73 |

| (9.51) | (4.75) | (2.97) | |

| Youngest | −5.14 | 12.79 * | −0.96 |

| (12.52) | (6.37) | (3.69) | |

| Mean | 317.98 | 23.77 | 85.15 |

| R2 | 0.80 | 0.55 | 0.72 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wikle, J.; Ackert, E. Child Citizenship Status in Immigrant Families and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110507

Wikle J, Ackert E. Child Citizenship Status in Immigrant Families and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(11):507. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110507

Chicago/Turabian StyleWikle, Jocelyn, and Elizabeth Ackert. 2022. "Child Citizenship Status in Immigrant Families and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings" Social Sciences 11, no. 11: 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110507

APA StyleWikle, J., & Ackert, E. (2022). Child Citizenship Status in Immigrant Families and Differential Parental Time Investments in Siblings. Social Sciences, 11(11), 507. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110507