The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany

Abstract

:1. Introduction

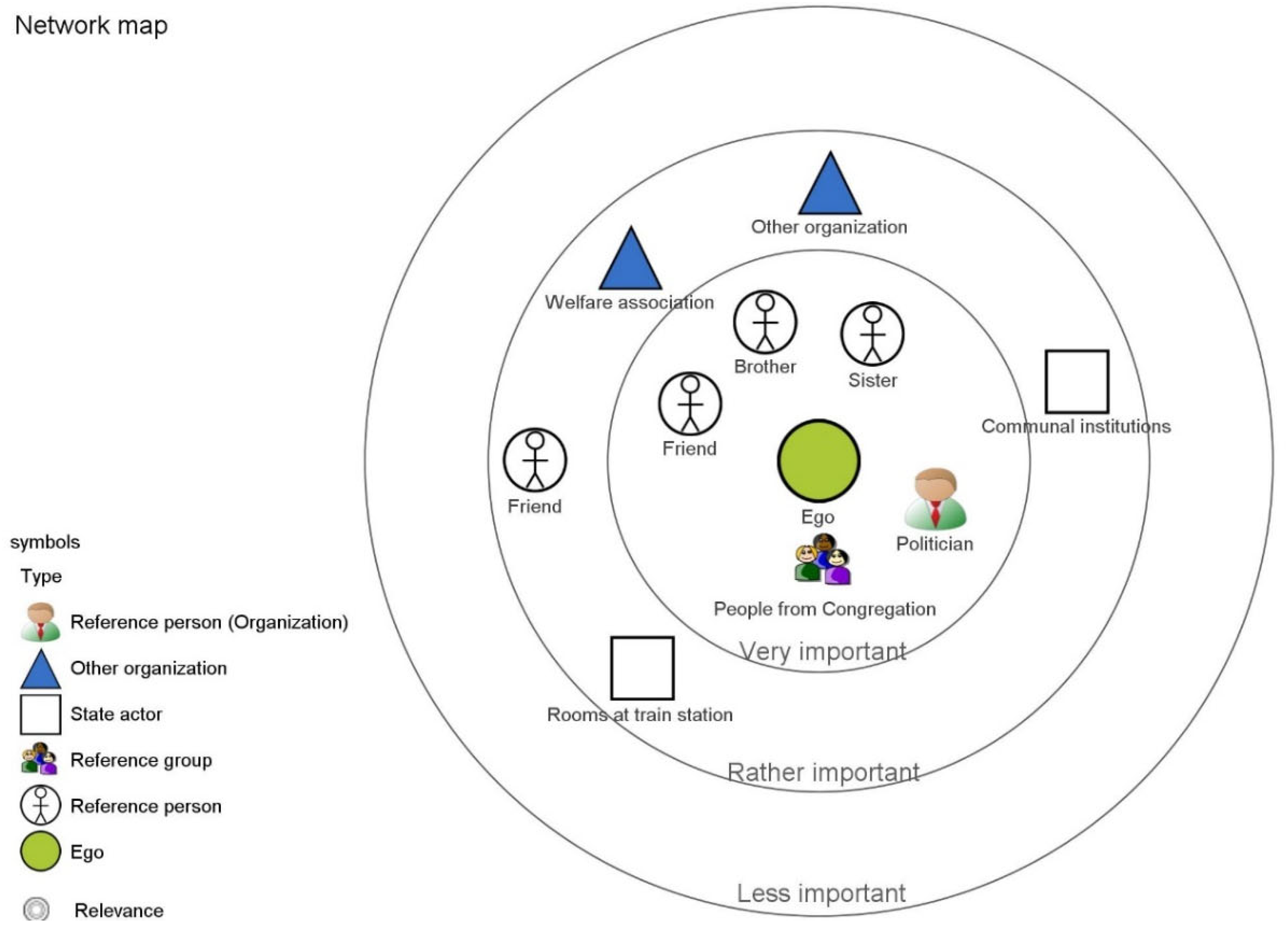

2. Social Protection, Emotions, Belonging, and Migrant Organizations

3. Materials and Methods

4. Results

4.1. Adult Movers

Without work, without language, without social contact, no activities, and just having to wait, what will happen, will [the asylum application] be rejected? Will I be sent back to Turkey or can I stay here? And these thoughts, this insecurity… yes, insecurity… Yes, of course, I received social security, but I was not used to expecting anything from others. I would say that this was not good for me.(Orhan, 52 years old, from Turkey)

When I want to meet people and make friends, when I want to learn something, I need to go there [to the Dersim community], because our people are there and when you are there you can meet people and exchange ideas. We support each other and the children will get to know each other. And this further opens other doors.(Orhan, 52 years old, from Turkey)

Yes, we are like a small family. And when you face any challenges, for example, these three families that have heavily handicapped children, they immediately exchange information. Which doctor do you go to, is he good or bad? And what do you do, what path did you take? And they share these difficult issues with each other. Or someone works in a factory and knows that they are looking for new employees. For example, in the banking sector. Then he will ask if someone is looking for employment or if he already knows who is looking for a job. Then he immediately calls them and says ‘Are you still looking for a job?’ Or, when I came here, I asked: ‘I don’t have a doctor here, which would you recommend?’ Where should I go? Is it good or not?’ and so on, based on these recommendations. Or, if parents have problems at school, for example, they come to me: ‘Yes, our child has this and that, what would you recommend?’ And you could always call and ask, in any situation, whether you have a disabled child, whether you look for a job if you have problems filling out a form, or families who have problems with an institution and need a translator; no matter what, we always know who can do what, who could help where. You offer to help yourself or others and ask them to accompany them to an agency or complete a form. That is how it usually works.(Orhan, 52 years old, from Turkey)

I am from Syria. I came with my family to Germany in 2015. As you know, there has been a war for ten years and many problems. And because of my health problems, we wanted to go to Germany. And we also have relatives in Germany. And we could move to Germany without any problems because they wanted to support us at the beginning. But when we arrived, we had to apply for asylum at the agency. And that… Of course, at first, language was a big problem for us. In the first city where we stayed, our children could go to school after one week. That was in the fall of 2015. Two of my children went to the preparation class, the youngest went to daycare. And my husband participated in an integration course for three months. And due to my health, I was unable to join these courses, which was a problem for me. And the city, a citizen in particular, she helped me. And so many people helped us learn the language. A professor and a woman always came to us and we often talked about many things. We lived there for ten months, and then we moved. And I was still motivated to learn the language. So my little boy went to another daycare facility. And then he went to the first grade and there was a cafe in the parent language. And this café was held every week, and I went there every week to learn the language. And through this café I met a Turkish woman. And she was active in International Women. And she also invited me there. […] And I met a woman who also came here, to Kurdo e.V.(Suleika, 43 years old, from Syria)

4.2. The German-Born

However, I must say that young people who now go to university do not need the community as much as they used to. Most of them are quite comfortable. They make use of opportunities provided by the system to receive information. That was different in previous generations, but in my opinion, this has changed.(Levent, 41, born in Germany, parents migrated from Turkey)

The Alevite congregations accomplished a lot in the sense that these children and adolescents can carry their identities in Germany with self-confidence, as the new normal, with naturalness. In Turkey, for example, I still pay attention to this, although I am a grown man now. I will not discuss this question. This sometimes leads to difficult situations, and I prefer to avoid them. But this is the most important aspect, in my opinion: self-esteem as Alevites, self-confidence. And a natural and easy self-understanding not based on unnaturalness or hiding your background or your cultural heritage, without having to identify with it too much, but that you can simply say, yes, my parents have Alevite roots, and that’s nothing special. I mean nothing special in the sense that I don’t have to hide it; I don’t have to talk about it in silence, but with self-confidence.(Levent, 41, parents migrated from Turkey)

Maybe we also reduce the barriers to visit the authorities, for refugees or migrants who did not feel like going to the foreign registration office 20 years ago when they could not speak the language. My father now also volunteers and is far beyond me. But 20 or 25 years ago, the barrier was much lower when you accompanied someone. When you said: Come on, I will take you with me. You can talk and if something happens, I am there.(Ufuk, 31, parents migrated from Turkey)

I am very happy with the perspective on life and the world that we share here. This is cosmopolitanism. That is why I am keen to support Gemeinsam Dortmund e.V. because I identify with it. I cannot identify with anything if I am excluded because I do not have a beard. Things like that. Here, all are welcome.(Ufuk, 31, parents from Turkey)

4.3. 1.5. Generation: Transnational Teens

I don’t worry about financial security or things like that here in Germany, because there is always a chance to work. If I were living in Turkey or Syria now, this would probably be very different because then I would not trust that I could use music to build a career. Well, here the chances are also moderate that music makes for a sufficient income. But I also think that if it is really bad that I cannot finance myself, then I would always have the option to look for a job in some way. Even if it is not a job, there is Jobcentre and offers like that, where you do not immediately starve when you do not have money. That is why I feel safe in this life, I simply feel safe here. There is nothing that makes me feel insecure. I have a good high school diploma, and others go to work after 10th grade and go on with their lives, so I am not afraid.(Najim, 17, from Syria)

Because the church, not as a religious institution, but as social contact, has a lot to offer older people who have far fewer opportunities because they are not so mobile anymore, fewer opportunities because they are not socialized in the same way as the following generations. Most of them do not even speak good German. And, based on their intellectual skills, they also have different opportunities. So, this generation is often the guest worker generation who came to Germany; ideally, the second generation, but rather the first generation. Yes, and most of them were illiterates and came from villages and would have had a hard time in Greece, and even harder here. They managed to find their way here, which I find very remarkable, but the older they get and the fewer their contacts, naturally, the natural fluctuation (laughing), the more important these institutions are for these people. And I think that the Greek associations had a peak sometime during the 1980s. They were very active, even if almost all associations were politically motivated.(Anthea, 53 years, from Greece)

If someone asks, ‘Where are you from?’ ‘I am from Greece’. First, you cannot say so simply, ‘I am from Greece’. Because: Yes, my children speak, they speak Greek well, but their Greek is not nearly as good as their German, English, Spanish, or whatever. And I also only know Greece from holidays. And we are still lucky to have family, close family members living in Greece. My siblings live in Greece, so our contact is very close. And this makes this question a bit easier. Because my children found their answer to this question: Home is where you have people who love me! And in Greece some people love them (laughing). That’s their family. And here, it’s their friends. That is something different. Friends are diverse, but the family is unambiguous and only Greek. So, we try to differentiate in this way because it is not easy to answer this question. And when we are in Greece and someone asks ‘Where are you from?’ Then it gets complicated. Then you cannot, you do not feel German, but you are not Greek either.(Anthea, 53 years, from Greece)

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | Although some authors decidedly distinguish between emotion and affect as different aspects of human feelings, in this article we follow scholarship that suggests using them interchangeably (Gorton 2007). Therefore, the “affective” dimension of social protection refers to the emotions at play in the context of managing social risks. |

| 2 | Especially used in the literature on marketing and branding, emotional attachment here refers to “how one becomes emotionally ‘wired’” in the “emotional environment” of the MO, i.e., the ways people develop emotional bonds through their engagement with their MOs (Donley 1993, p. 5). |

References

- Amelina, Anna. 2010. Searching for an Appropriate Research Strategy on Transnational Migration: The Logic of Multi-Sited Research and the Advantage of the Cultural Interferences Approach. Forum: Qualitative Social Research FQS 11: 17. [Google Scholar]

- Amelina, Anna. 2022. Knowledge production for whom? Doing migrations, colonialities and standpoints in non-hegemonic migration research. Ethnic and Racial Studies 45: 2393–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelina, Anna, and Niklaas Bause. 2020. Forced migrant families’ assemblages of care and social protection between solidarity and inequality. Journal of Family Research 32: 415–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amelina, Anna, and Thomas Faist. 2008. Turkish Migrant Associations in Germany: Between Integration Pressure and Transna-tional Linkages. Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 24: 91–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Amelina, Anna, Emma Carmel, Ann Runfors, and Elisabeth Scheibelhofer, eds. 2020. Boundaries of European Social Citi-Zenship. Transnational Social Security in Regulations, Discourses, and Experiences. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Antonsich, Marco. 2010. Searching for—Belonging: An analytical framework. Geography Compass 4: 644–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Aşkın, Basri, Anke Wagner, Mesut Tübek, and Monika A. Rieger. 2018. Die Rolle von Migrantenselbstorganisationen in der Gesundheitsversorgung. Ein integrativer Review. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen 139: 37–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassar, Loretta. 2008. Missing kin and longing to be together: Emotions and the construction of co-presence in transnational relationships. Journal of Intercultural Studies 29: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, Karolina. 2019. Cultures of Transnationality in European Migration. Abingdon: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Barglowski, Karolina. 2021. Transnational parenting in settled families: Social class, migration experiences and child rearing among Polish migrants in Germany. Journal of Family Studies, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, Karolina, and Lisa Bonfert. 2022a. Beyond integration versus homeland attachment: How migrant organizations affect processes of anchoring and embedding. Ethnic and Racial Studies. forthcoming. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, Karolina, and Lisa Bonfert. 2022b. Migrant organisations, belonging and social protection. The role of migrant organisations in migrants’ social risk-averting strategies. International Migration, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barglowski, Karolina, and Paula Pustulka. 2018. Tightening early childcare choices:–Gender and social class ine-qualities among Polish mothers in Germany and the UK. Comparative Migration Studies 6: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baxter, Kate, and Caroline Glendinning. 2013. The Role of Emotions in the Process of Making Choices About Welfare Services: The experiences of disabled people in England. Social Policy and Society 12: 439–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benson, Michaela. 2016. Deconstructing belonging in lifestyle migration: Tracking the emotional negotiations of the British in rural France. European Journal of Cultural Studies 19: 481–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bericat, Eduardo. 2016. The Sociology of Emotions: Four decades of progress. Current Sociology 64: 491–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilecen, Başak. 2015. Home-Making Practices and Social Protection across Borders: An Example of Turkish Migrants Living in Germany. Dordrecht: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Bilecen, Başak. 2020. Asymmetries in transnational social protection: Perspectives of migrants and non-migrants. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences 689: 168–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilecen, Başak, and Karolina Barglowski. 2015. On the Assemblages of Informal and Formal Transnational Social Protection. Population, Space and Place 21: 203–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blachnicka-Ciacek, Dominika, Agnieszka Trabka, Irma Budginaite-Mackine, Violetta Parutis, and Paula Pustulka. 2021. Do I deserve to belong? Migrants’ Migrant perspectives on the debate of merit and belonging. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 47: 3805–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, Paolo. 2014. What is in a house (migrant)? Changing Domestic Spaces, the negotiation of belonging and Home in Ecuadorian migration. Housing, Theory and Society 31: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boccagni, Paolo, and Pierrette Hondagneu-Sotelo. 2021. Integration and the struggle to turn space into ‘our’ place: Homemaking as a way beyond the stalemate of assimilationism versus transnationalism. International Migration. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonfert, Lisa, Eva Günzel, Ariana Kellmer, Karolina Barglowski, Ute Klammer, Sören Petermann, Ludger Pries, and Thorsten Schlee. 2022. Migrantenorganisationen und soziale Sicherung. In IAQ-Report. Essen: University Duisburg-Essen. [Google Scholar]

- Carmel, Emma, and Bozena Sojka. 2021. Beyond Welfare Chauvinism and Deservingness. Rationales of Belonging as a Conceptual Framework for the Politics and Governance of Migrant Rights. Journal of Social Policy 50: 645–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cvetkovich, Ann. 1992. Mixed Feelings: Feminism, Mass Culture and Victorian Sensationalism. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- D’Angelo, Alessio. 2015. Migrant Organizations: Embodied Community Capital? In Migrant Capital. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 83–101. [Google Scholar]

- Dahinden, Janine. 2012. Transnational belonging, nonethnic forms of identification and diverse mobilities: Rethinking migrant inte-gration? In Migrations: Interdisciplinary Perspectives. Vienna: Springer, pp. 117–28. [Google Scholar]

- Dankyi, Ernestina, Valentina Mazzucato, and Takyiwaa Manuh. 2017. Reciprocity in global social protection: Providing care to migrants’ children. Oxford Development Studies 45: 80–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolberg, Pnina, and Karin Amit. 2022. On a fast-track to adulthood: Social integration and identity formation experiences of young-adults of 1.5 generation immigrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donley, Margarete G. 1993. Attachment and the Emotional Unit. Clinical Theory and Practice 32: 3–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eurofound. 2015. Access to Social Benefits: Reducing Non-Take-Up. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Faist, Thomas. 2017. Transnational Social Protection in Europe: A social inequality perspective. Oxford Development Studies 45: 20–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faist, Thomas, Başak Bilecen, Karolina Barglowski, and Joanna Jadwiga Sienkiewicz. 2015. Transnational Social Protection. Migrant Strategies and Patterns of Inequalities. Population, Space and Place 21: 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fauser, Margit. 2016. Migrants and Cities: Accommodation of Migrant Organizations in Europe. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Godin, Marie. 2020. Far from a burden: EU migrants as pioneers of a European social protection system from below. International Migration 58: 136–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gorton, Kristyn. 2007. Theorizing emotion and affect: Feminist engagements. Feminist Theory 8: 333–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greco, Monica, and Paul Stenner. 2013. Emotions: A Social Science Reader. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Grzymala-Kazlowska, Aleksandra. 2016. Social anchoring: Immigrant identity, security, and integration reconnected? Sociology 50: 1123–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halm, Dirk, Martina Sauer, Saboura Naqshband, and Magdalena Nowicka. 2020. Wohlfahrtspflegerische Leistungen von Säkularen Migrantenorganisationen in Deutschland, unter Berücksichtigung der Leistungen für Geflüchtete. Baden-Baden: Nomos. [Google Scholar]

- Hernández-Plaza, Sonia, Enrique Alonso-Morillejo, and Carmen Pozo-Muoz. 2006. Social support interventions in migrant populations. British Journal of Social Work 36: 1151–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoesch, Kirsten, and Gesa Harbig. 2019. Migrantenorganisationen in der Flüchtlingsarbeit: Neue Chancen für die kommunal Integrationspolitik? Überlegungen anhand des Projekts Samo.fa und des lokalen Verbundes VMDO. In Flüchtigkeiten. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, pp. 103–31. [Google Scholar]

- ILO International Labour Organization. 2021. World Social Protection Report 2020–2022. Social Protection at the Crossroads, in Pursuit of a Better Future. Geneva: International Labour Office. [Google Scholar]

- Jupp, Eleanor. 2022. Emotions, affect, and social policy: Austerity and Children’s Centers in the UK. Critical Policy Studies 16: 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klammer, Ute, Simone Leibner, and Sigrid Leitner. 2017. Leben im transformierten Sozialstaat: Sozialpolitische Perspektiven auf Soziale Arbeit: Überlegungen zur Zusammenführung zweier Forschungsstränge. Soziale Passagen 9: 71–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klok, Jolien, Theo van Tilburg, Tineke Fokkema, and Bianca Suanet. 2020. Comparing the transnational behaviour of generations of migrants: The role of the transnational convoy and integration. Comparative Migration Studies 8: 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lafleur, Jean-Michel, and Maria Vivas Romero. 2018. Combining transnational and intersectional approaches to immigrant social protection: The case of Andean families’ access to health. Comparative Migration Studies 6: 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levitt, Peggy. 2004. Redefining the boundaries of belonging: The institutional character of transnational religious life. Sociology of Religion 65: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levitt, Peggy, Jocelyn Viterna, Armin Mueller, and Charlotte Lloyd. 2017. Transnational social protection: Setting the agenda. Oxford Development Studies 45: 2–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Louie, Vivian. 2006. Growing up ethnic in transnational worlds: Identities among second-generation Chinese and Dominicans. Identities. Global Studies in Culture and Power 13: 363–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAuslan, Ian, and Rachel Sabates-Wheeler. 2011. Structures of Access and Social Provision for Migrants. In Migration and Social Protection. Claiming Social Rights Beyond Borders. Edited by Rachel Sabates-Wheeler and Rayah Feldman. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, Rahsaan. 2010. Evaluating Migrant Integration: Political attitudes between generations in Europe. International Migration Review 44: 25–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mayblin, Lucy, and Poppy James. 2019. Asylum and refugee support in the UK: Civil society filling the gaps? Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 375–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Osipovic, Dorota. 2015. Conceptualisations of Welfare Deservingness by Polish Migrants in the UK. Journal of Social Policy 44: 729–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palash, Polina, and Virginie Baby-Collin. 2018. The Other Side of Need. Reverse economic flows to ensure transnational social protection of migrants. Population, Space and Place 25: e2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauschmayer, Felix. 2005. Linking Emotions to Needs: A Comment on Mindsets, Rationality and Emotion in Multi-criteria Decision Analysis. Journal of Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis 13: 187–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Louise. 2007. Migrant women, social networks, and motherhood: The experiences of Irish nurses in Britain. Sociology 41: 295–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, Louise. 2018. Differentiated embedding: Polish migrants in London negotiating belonging over time. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel, and Rayah Feldman. 2011. Migration and Social Protection. Claiming Social Rights Beyond Borders. Rethinking International Development series; Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Safi, Mirna. 2017. Varieties of Transnationalism and Its Changing Determinants across Immigrant Generations: Evidence from French data. International Migration Review 52: 853–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saksela-Bergholm, Sanna. 2019. Welfare Beyond Borders: Informal social protection strategies of Filipino transnational families. Social Inclusion 7: 221–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweyher, Mateus, Gunhild Odden, and Kathy Burrell. 2019. Abuse or Underuse? Narratives of Polish Migrants Claiming Social Benefits in the UK in Times of Brexit. Central and Eastern European Migration Review 8: 101–22. [Google Scholar]

- Serra Mingot, Ester, and Valentina Mazzucato. 2018. Providing social protection to mobile populations: Symbiotic relationships between migrants and welfare institutions. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44: 2127–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- SVR Forschungsbereich beim Sachverständigenrat deutscher Stiftungen für Integration und Migration (SVR). 2020. Vielfältig Engagiert–Breit Vernetzt–Partiell Eingebunden? Berlin: Migrantenorganisationen als gestaltende Kraft in der Gesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- van Oorschot, Wim, Femke Roosma, Bart Meuleman, and Tim Reeskens, eds. 2017. The Social Legitimacy of the Targeted Welfare. Attitudes towards Welfare-Deservingness. Cheltenham, Gloucestershire and Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wetherell, Margaret. 2013. Affect and discourse: What is the problem? From affect as excess to affective/cognitive practice. Subjectivity 6: 349–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wise, Amanda, and Selvaraj Velayutham. 2017. Transnational affect and emotion in migration research. International Journal of Sociology 47: 116–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barglowski, K.; Bonfert, L. The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110505

Barglowski K, Bonfert L. The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(11):505. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110505

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarglowski, Karolina, and Lisa Bonfert. 2022. "The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany" Social Sciences 11, no. 11: 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110505

APA StyleBarglowski, K., & Bonfert, L. (2022). The Affective Dimension of Social Protection: A Case Study of Migrant-Led Organizations and Associations in Germany. Social Sciences, 11(11), 505. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110505