Political Attitudes and Participation among Young Arab Workers: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Workers in Five Arab Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Research Context

- Understanding political participation is critical for Arab governments to address population needs. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to give attention to informal workers’ political participation in Arab countries and how this could be enhanced. As such, this contributes a progressive step towards the formalization of labour and achievement of Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 8 on decent jobs.

- The paper provides an Arab region perspective on informality and political participation which is missing in the existing literature. This in turn advances scholarship on a politically important region of the world and raises the issue of whether political participation in developing country contexts simply takes on particular forms rather than being largely absent (Teobaldelli and Schneider 2013).

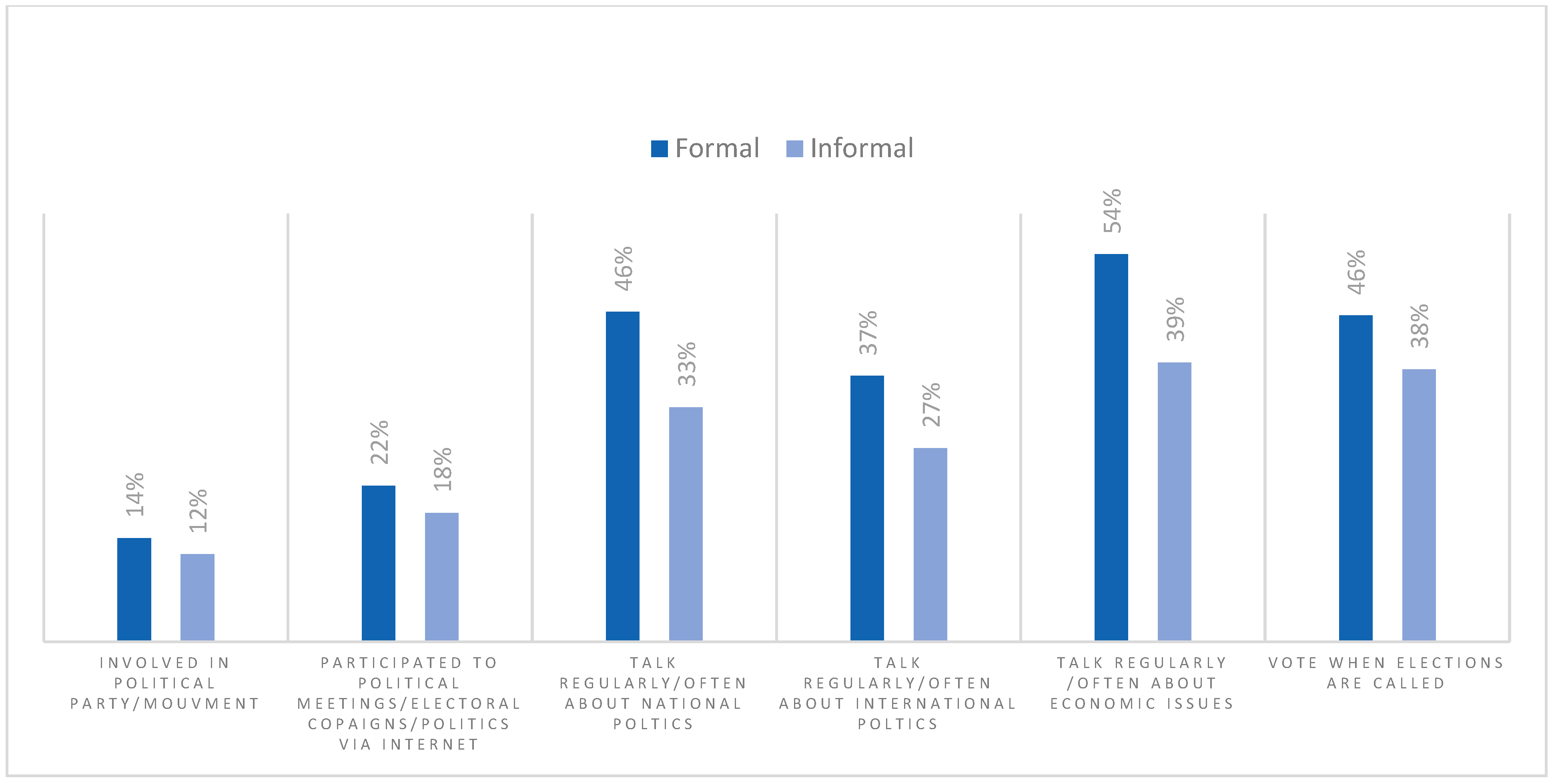

- The paper provides a more robust analysis of political participation beyond the limited scope of voting (Daenekindt et al. 2019) and adds other measures such as affiliation to a political party, participating in political meetings, and frequency of discussion of political topics.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. The Dependent Variables

3.3. The Independent Variables

4. Method

5. Empirical Analysis

5.1. Job Satisfaction

5.2. Gender

5.3. Confidence in Government

5.4. Age

5.5. Education

5.6. Marital Status

5.7. Employment Status

5.8. Urban vs. Rural Differences

5.9. Sectorial Analysis

5.10. Cross Country Comparison

6. Conclusions and Key Policy Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Model 1 | Model2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable VIF | VIF | Variable | VIF | Variable VIF | Variable | VIF | |

| Informal | 8.31 | Informal | 1.35 | Informal | 1.41 | Informal | 1.23 |

| Gender | 3.48 | Job satisfaction | 1.12 | Job satisfaction | 1.13 | Job satisfaction | 1.12 |

| Confidence in government | 4.98 | Gender | 1.07 | Gender | 1.11 | Gender | 1.07 |

| Education | 6.87 | Confidence in government | 1.01 | Confidence in government | 1.01 | Confidence in government | 1 |

| Occupational statuts | Age | 1.27 | Age | 1.35 | Age | 1.27 | |

| Unemployed | 1.15 | Married | 1.14 | Education | 1.28 | Married | 1.14 |

| Student | 1.12 | Occupational status | Married | 1.14 | Occupational status | ||

| Inactive | 1.08 | Unemployed | 1.1 | Occupational status | Unemployed | 1.1 | |

| Job position | Student | 1.11 | Unemployed | 1.11 | Student | 1.11 | |

| Employee | 3.91 | Inactive | 1.05 | Student | 1.17 | Inactive | 1.04 |

| Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.53 | Job position | Inactive | 1.05 | Job position | ||

| Urban | 2.6 | Employee | 1.46 | Job position | Employee | 1.45 | |

| Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.44 | Employee | 1.46 | Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.44 | ||

| Urban | 1.07 | Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.43 | Urban | 1.07 | ||

| private | 1.15 | Urban | 1.08 | ||||

| Private | 1.16 | ||||||

| Mean VIF | 3.5 | Mean VIF | 1.18 | Mean VIF | 1.21 | Mean VIF | 1.17 |

| Involved in Political Party/Mouvment | Participated in Political Meeting/Electoral Campaigns/Politics via the Internet | Speal about National Politics Regularly/Often | Speak about International Politics Regularly/Often | Speak about Economic Issues Regularly/Often | Vote When Election Are Called | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Formal | Informal | Formal | Informal | Formal | Informal | Formal | Informal | Formal | Informal | Formal | Informal |

| Algeria | 6.11 | 6.08 | 21.4 | 27.66 | 38 | 37.19 | 37.11 | 39.82 | 46.72 | 39.38 | 55.46 | 38.3 |

| Egypt | 8.51 | 4.21 | 8.51 | 8.24 | 47.51 | 32.48 | 31.21 | 19.7 | 44.68 | 34.81 | 73.76 | 63.19 |

| Lebanon | 20.29 | 22.49 | 25 | 16.63 | 55.3 | 34.96 | 38.53 | 28.61 | 72.06 | 54.04 | 28.53 | 15.65 |

| Morocco | 34.34 | 25.67 | 53.54 | 37.97 | 28.28 | 23.26 | 29.29 | 20.59 | 26.26 | 24.06 | 35.35 | 30.75 |

| Tunisia | 6.96 | 4.41 | 7.59 | 4.96 | 48.73 | 36.91 | 44.93 | 31.68 | 53.16 | 44.08 | 50 | 33.33 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Morocco) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| Informal | 0.630 | 0.802 | 1.134 | 0.845 | 1.180 |

| (0.333) | (0.357) | (0.273) | (0.283) | (0.629) | |

| Job Satisfaction | 1.827 | 0.801 | 0.582 ** | 0.945 | 0.916 |

| (0.842) | (0.340) | (0.158) | (0.294) | (0.407) | |

| Male | 0.466 | 0.398 * | 2.182 *** | 1.290 | 1.432 |

| (0.246) | (0.208) | (0.545) | (0.480) | (0.865) | |

| Confident in government & political institutions | 1.406 | 1.617 ** | 8.258 *** | 0.891 | 1.801 * |

| (0.341) | (0.357) | (3.580) | (0.185) | (0.614) | |

| Age | 1.105 * | 0.965 | 1.010 | 0.924 ** | 0.968 |

| (0.0618) | (0.0707) | (0.0301) | (0.0337) | (0.0717) | |

| Married | 0.415 | 2.248 | 1.933 *** | 2.057 ** | 0.721 |

| (0.233) | (1.118) | (0.440) | (0.619) | (0.395) | |

| Education | 0.864 | 1.646 * | 1.158 | 1.147 | 2.153 *** |

| (0.244) | (0.489) | (0.145) | (0.166) | (0.529) | |

| 2. Employee | 0.819 | 0.951 | 0.757 | 1.325 | 0.977 |

| (0.445) | (0.808) | (0.168) | (0.404) | (0.624) | |

| 3. Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.481 | 4.990 * | 0.733 | 1.411 | 0.393 |

| (0.949) | (4.489) | (0.318) | (0.934) | (0.363) | |

| 2. Industry | 1.049 | 3.906 ** | 0.665 | 0.907 | 5.116 |

| (1.286) | (2.562) | (0.429) | (0.491) | (6.004) | |

| 3. Construction | 2.859 | 2.048 | 2.384 | 0.994 | 3.145 |

| (3.071) | (1.663) | (1.545) | (0.596) | (3.554) | |

| 4. Health Services | 0.673 | 0.720 | 0.831 | 2.865 | |

| (0.992) | (0.818) | (0.634) | (3.885) | ||

| 5. Education sector | 0.325 | 3.149 | 0.851 | 2.087 | 5.381 |

| (0.569) | (3.197) | (0.534) | (1.759) | (7.137) | |

| 6. Trade | 1.476 | 0.781 | 1.141 | 0.811 | 1.938 |

| (1.590) | (0.651) | (0.646) | (0.361) | (2.409) | |

| 7. Other commercial services | 1.709 | 3.199 | 0.954 | 1.283 | 3.992 |

| (1.899) | (2.509) | (0.528) | (0.631) | (4.747) | |

| 8. Administration, non-commercial services | 0.308 | 5.018 ** | 0.611 | 0.551 | |

| (0.426) | (3.522) | (0.396) | (0.317) | ||

| Urban | 2.922 ** | 1.328 | 0.969 | 1.240 | 1.478 |

| (1.558) | (0.554) | (0.222) | (0.376) | (0.856) | |

| Constant | 0.00569 ** | 0.0109 * | 0.00996 *** | 1.465 | 0.00116 ** |

| (0.0127) | (0.0278) | (0.0139) | (1.786) | (0.00337) | |

| Observations | 549 | 658 | 731 | 347 | 455 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Morocco) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| Informal | 1.063 | 0.889 | 0.358 *** | 0.685 | 0.785 |

| (0.363) | (0.408) | (0.0937) | (0.202) | (0.437) | |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.795 | 0.869 | 0.329 *** | 0.846 | 0.738 |

| (0.207) | (0.299) | (0.0903) | (0.248) | (0.328) | |

| Male | 0.964 | 1.944 | 2.237 *** | 1.458 | 2.837 |

| (0.306) | (0.974) | (0.580) | (0.572) | (1.908) | |

| Confident in government & political institutions | 1.963 *** | 1.572 ** | 9.527 *** | 0.781 | 0.768 |

| (0.272) | (0.294) | (3.548) | (0.162) | (0.369) | |

| Age | 1.025 | 0.991 | 0.969 | 0.866 *** | 0.899 |

| (0.0365) | (0.0473) | (0.0323) | (0.0304) | (0.0669) | |

| Married | 0.830 | 0.624 | 1.020 | 1.916 ** | 1.081 |

| (0.230) | (0.232) | (0.235) | (0.532) | (0.565) | |

| Education | 0.785 | 0.893 | 1.331 ** | 1.034 | 2.789 *** |

| (0.119) | (0.139) | (0.171) | (0.153) | (0.773) | |

| 2. Employee | 0.867 | 1.047 | 0.366 *** | 0.940 | 2.573 |

| (0.259) | (0.569) | (0.0887) | (0.267) | (2.164) | |

| 3. Contributing family workers and apprentices | 0.996 | 1.193 | 0.578 | 0.830 | 1.731 |

| (0.420) | (0.834) | (0.259) | (0.500) | (1.522) | |

| 2. Industry | 0.629 | 1.094 | 0.552 | 1.285 | 0.510 |

| (0.340) | (0.658) | (0.346) | (0.648) | (0.354) | |

| 3. Construction | 1.253 | 0.767 | 0.817 | 1.185 | 0.355 |

| (0.519) | (0.469) | (0.535) | (0.704) | (0.259) | |

| 4. Health Services | 0.924 | 0.497 | 0.665 | ||

| (0.532) | (0.601) | (0.506) | |||

| 5. Education sector | 0.591 | 3.472 | 1.078 | 1.843 | 1.266 |

| (0.431) | (3.148) | (0.651) | (1.564) | (1.050) | |

| 6. Trade | 0.674 | 1.150 | 0.484 | 0.846 | 0.291 |

| (0.288) | (0.678) | (0.268) | (0.371) | (0.252) | |

| 7. Other commercial services | 0.626 | 1.536 | 0.460 | 0.733 | 0.911 |

| (0.270) | (0.893) | (0.248) | (0.329) | (0.587) | |

| 8. Administration, non-commercial services | 0.680 | 1.032 | 0.548 | 0.513 | 0.501 |

| (0.346) | (0.710) | (0.330) | (0.268) | (0.391) | |

| Urban | 1.713 ** | 1.589 | 0.960 | 0.847 | 1.029 |

| (0.433) | (0.483) | (0.233) | (0.271) | (0.516) | |

| Constant | 0.157 | 0.0511 | 0.434 | 55.44 *** | 0.0345 |

| (0.227) | (0.109) | (0.554) | (65.56) | (0.0914) | |

| Observations | 549 | 658 | 731 | 347 | 490 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Morocco) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| Informal | 0.613 | 0.861 | 0.319 *** | 1.384 | 0.875 |

| (0.199) | (0.218) | (0.107) | (0.445) | (0.256) | |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.663 * | 1.266 | 0.868 | 1.027 | 0.954 |

| (0.165) | (0.245) | (0.286) | (0.308) | (0.226) | |

| Male | 2.299 *** | 0.820 | 1.020 | 1.017 | 1.370 |

| (0.692) | (0.226) | (0.272) | (0.373) | (0.369) | |

| Confident in government & political institutions | 1.184 | 1.057 | 1.320 | 1.935 ** | |

| (0.196) | (0.135) | (0.251) | (0.590) | ||

| Age | 1.004 | 1.030 | 0.995 | 0.963 | 1.071 ** |

| (0.0359) | (0.0292) | (0.0327) | (0.0329) | (0.0373) | |

| Married | 1.267 * | 1.161 | 1.363 ** | 1.532 *** | 1.430 *** |

| (0.180) | (0.112) | (0.188) | (0.208) | (0.186) | |

| Education | 2.588 *** | 0.984 | 1.876 ** | 1.319 | 1.740 * |

| (0.788) | (0.203) | (0.520) | (0.375) | (0.547) | |

| 2. Employee | 0.773 | 0.795 | 0.805 | 1.069 | 0.868 |

| (0.236) | (0.262) | (0.236) | (0.304) | (0.300) | |

| 3. Contributing family workers and apprentices | 1.530 | 0.765 | 1.036 | 0.488 | 1.794 |

| (0.707) | (0.318) | (0.494) | (0.336) | (0.770) | |

| 2. Industry | 0.623 | 1.350 | 1.588 | 1.280 | 0.835 |

| (0.327) | (0.448) | (0.927) | (0.654) | (0.386) | |

| 3. Construction | 1.528 | 0.914 | 4.471 ** | 0.911 | 1.116 |

| (0.743) | (0.292) | (3.146) | (0.520) | (0.529) | |

| 4. Health Services | 0.628 | 1.454 | 10.33 ** | 1.288 | |

| (0.381) | (0.733) | (11.84) | (0.980) | ||

| 5. Education sector | 1.538 | 0.673 | 2.584 | 1.901 | 0.466 |

| (1.033) | (0.372) | (1.666) | (1.642) | (0.287) | |

| 6.Trade | 0.879 | 0.781 | 3.318 ** | 1.412 | 0.716 |

| (0.433) | (0.246) | (1.810) | (0.616) | (0.324) | |

| 7. Other commercial services | 1.235 | 1.969 ** | 4.799 *** | 3.521 *** | 0.604 |

| (0.601) | (0.678) | (2.550) | (1.639) | (0.283) | |

| 8. Administration, non-commercial services | 0.828 | 1.473 | 3.761 ** | 2.049 | 0.330 * |

| (0.454) | (0.555) | (2.361) | (1.069) | (0.188) | |

| Urban | 0.936 | 0.626 ** | 0.926 | 1.414 | 1.036 |

| (0.250) | (0.117) | (0.251) | (0.419) | (0.266) | |

| Constant | 2.308 | 0.906 | 5.955 | 0.209 | 0.170 |

| (3.195) | (0.950) | (8.475) | (0.250) | (0.222) | |

| Observations | 549 | 658 | 683 | 347 | 515 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Morocco) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| Informal | 0.544 ** | 0.906 | 0.445 *** | 0.889 | 1.013 |

| (0.145) | (0.249) | (0.117) | (0.275) | (0.257) | |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.770 | 1.057 | 0.674 | 0.706 | 1.263 |

| (0.173) | (0.212) | (0.271) | (0.211) | (0.278) | |

| Male | 0.699 | 1.652 * | 1.597 * | 1.327 | 0.815 |

| (0.179) | (0.482) | (0.427) | (0.492) | (0.195) | |

| Confident in government & political institutions | 1.605 *** | 1.706 *** | 5.861 *** | 1.160 | 1.620 ** |

| (0.214) | (0.272) | (2.171) | (0.219) | (0.395) | |

| Age | 1.124 *** | 1.174 *** | 2.052 *** | 1.033 | 1.190 *** |

| (0.0332) | (0.0371) | (0.206) | (0.0354) | (0.0387) | |

| Married | 1.188 | 0.933 | 1.654 ** | 1.096 | 0.979 |

| (0.293) | (0.201) | (0.387) | (0.309) | (0.248) | |

| Education | 1.033 | 1.446 *** | 1.163 | 1.291 * | 1.668 *** |

| (0.133) | (0.148) | (0.162) | (0.181) | (0.208) | |

| 2. Employee | 0.777 | 0.818 | 0.512 ** | 0.815 | 1.020 |

| (0.199) | (0.304) | (0.146) | (0.237) | (0.322) | |

| 3. Contributing family workers and apprentices | 0.654 | 0.603 | 2.173 | 0.397 | 1.251 |

| (0.260) | (0.273) | (1.110) | (0.275) | (0.465) | |

| 2. Industry | 0.371 ** | 0.612 | 0.880 | 3.236 * | 1.254 |

| (0.161) | (0.224) | (0.577) | (1.992) | (0.501) | |

| 3. Construction | 0.433 ** | 0.424 ** | 1.456 | 2.266 | 1.215 |

| (0.168) | (0.152) | (0.977) | (1.494) | (0.495) | |

| 4. Health Services | 0.262 *** | 0.679 | 1.781 | 8.723 ** | 1.991 |

| (0.134) | (0.377) | (1.280) | (8.618) | (1.022) | |

| 5. Education sector | 0.268 ** | 0.466 | 0.917 | 3.668 | 0.788 |

| (0.158) | (0.290) | (0.606) | (3.168) | (0.453) | |

| 6. Trade | 0.323 *** | 0.560 | 0.820 | 2.718 ** | 0.666 |

| (0.128) | (0.207) | (0.488) | (1.357) | (0.279) | |

| 7. Other commercial services | 0.375 *** | 0.725 | 0.650 | 3.551 ** | 0.817 |

| (0.143) | (0.284) | (0.374) | (1.887) | (0.331) | |

| 8. Administration, non-commercial services | 0.550 | 0.373 ** | 0.542 | 2.830 * | 1.102 |

| (0.249) | (0.160) | (0.349) | (1.543) | (0.566) | |

| Urban | 0.948 | 0.470 *** | 0.798 | 1.000 | 0.692 |

| (0.212) | (0.0912) | (0.206) | (0.294) | (0.175) | |

| Constant | 0.277 | 0.0183 *** | 6.91e-10 *** | 0.0564 ** | 0.00164 *** |

| (0.318) | (0.0198) | (2.07e-09) | (0.0689) | (0.00198) | |

| Observations | 549 | 658 | 731 | 352 | 515 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Tunisia) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | ODDS Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| EMP315 | 0.994 | 0.442 ** | 1.140 | 0.718 | 0.679 |

| (0.357) | (0.166) | (0.205) | (0.188) | (0.279) | |

| Constant | 0.0655 *** | 0.226 ** | 0.223 *** | 0.621 | 0.104 *** |

| (0.0392) | (0.147) | (0.0658) | (0.293) | (0.0716) | |

| Observations | 558 | 687 | 749 | 473 | 521 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Tunisia) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| EMP315 | 1.549 * | 0.937 | 0.598 *** | 0.595 ** | 0.679 |

| (0.347) | (0.323) | (0.109) | (0.145) | (0.267) | |

| Constant | 0.190 *** | 0.103 *** | 0.557 ** | 1.507 | 0.122 *** |

| (0.0730) | (0.0653) | (0.158) | (0.670) | (0.0807) | |

| Observations | 558 | 687 | 749 | 473 | 521 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Tunisia) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| EMP315 | 0.818 | 0.620 ** | 0.244 *** | 0.720 | 0.711 |

| (0.190) | (0.129) | (0.0623) | (0.174) | (0.171) | |

| Constant | 4.936 *** | 4.048 *** | 62.35 *** | 2.011 | 6.359 *** |

| (1.938) | (1.564) | (29.10) | (0.893) | (2.732) | |

| Observations | 558 | 687 | 749 | 473 | 521 |

| (Algeria) | (Egypt) | (Lebanon) | (Tunisia) | (Tunisia) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| EMP315 | 0.552 *** | 0.597 ** | 0.465 *** | 0.559 ** | 0.511 *** |

| (0.105) | (0.127) | (0.0844) | (0.143) | (0.101) | |

| Constant | 2.292 *** | 4.836 *** | 0.859 | 1.263 | 1.892 * |

| (0.723) | (1.914) | (0.237) | (0.588) | (0.647) | |

| Observations | 558 | 687 | 749 | 473 | 521 |

| 1 | See for example https://www.europarl.europa.eu/election-results-2019/en/turnout/ (accessed on 1 February 2022). |

| 2 | NDI website: https://www.ndi.org/middle-east-and-north-africa/morocco (accessed on 1 February 2022). |

| 3 | The Middle East Monitor online article: https://www.middleeastmonitor.com/20200224-protests-in-morocco-demanding-improvement-of-social-and-human-rights-conditions/ (accessed on 1 February 2022). |

| 4 | According to http://www.electionguide.org/, the voter turnout decreased from 63% and 60% (second round) in 2014 to 48% and 54% in 2019. |

| 5 | The question was worded as follows: “Could you tell me if you belong to [Political party; Political movement that is not a political party], as a sympathiser, participant, donor or volunteer? 1. Yes, as a sympathizer; 2. Yes, as a participant 3. Yes, as a donor 4. Yes, performing voluntary work 5. No 6. Never”. |

| 6 | The questions were worded as follows: Using this card, how often have you participated [a-Participate in party political meetings or activities; b-Participate in electoral campaigns; c-Political participation via the internet] in the past 12 months? 1. Every day 2. More than once a week 3. About once a week 4. About once a month 5. A few times a year 6. Never. The dummy is equal to 1 if the respondent picked one of the 5 first alternatives in at least one of the three questions (a, b and c). |

| 7 | Using this card, how often do you speak about [National political affairs; International and regional political affairs; Economic issues] with the following person [Mother, Father, Brothers/sisters, Friends, Wife/husband, Colleagues/classmates, others]? 1. Regularly 2. Often 3. Sometimes 4. Rarely 5. Never. The alpha Cronbach is calculated combing the all the questions/alternatives. |

| 8 | Do you vote when elections are called? 1. Always 2. Often 3. Sometimes 4. Rarely 5. Never. We grouped the two first alternative into one category for people who vote (patriciate to politics). |

| 9 | It is measured, in the survey, using the following question: Are you satisfied with your job? [1] Very satisfied [2] satisfied [3] dissatisfied [4] Very dissatisfied. |

| 10 | The stronger is the relationship between the two variables, the closest to 1 is the value of Gamma test. |

| 11 | Constant cut1—This is the estimated cut point on the latent variable used to differentiate lowest value of dependent variables from other values when values of the predictor variables are evaluated at zero. |

| 12 | These variables are a Likert scale ordered from (0) Not at all confident to (10) very confident. |

| 13 | This may be the reason why age’s coefficients were not significant in the two first models. |

| 14 | This reflects the number of possible combinations between the testing/secondary variables. |

| 15 | Student test has been used to test the significance of the coefficients, for the robustness check. |

References

- Aguilar, Edwin Eloy, Alexander Pacek, and Douglas S. Thornton. 1998. Political Participation among Informal Sector Workers in Mexico and Costa Rica. Prepared for delivery at the 1998 meeting of the Latin American Studies Association, The Palmer House Hilton Hotel, Chicago, Illinois, September 24–26; Available online: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/ar/libros/lasa98/Aguilar-Pacek-Thorton.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2022).

- Amat, Francesc, Carles Boix, Jordi Muñoz, and Toni Rodon. 2020. From Political Mobilization to Electoral Participation: Turnout in Barcelona in the 1930s. The Journal of Politics 82: 1559–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrighi, Barbara A., and David J. Maume. 1994. Workplace Control and Political Participation. Sociological Focus 27: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaad, Ragui. 2014. Making sense of Arab labor markets: The enduring legacy of dualism. IZA Journal of Labor & Development 3: 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, Andy, and Dalton Dorr. 2022. Labor Informality and the Vote in Latin America: A Meta-analysis. Latin American Politics and Society 64: 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Andy, and Vania Ximena Velasco-Guachalla. 2018. Is the Informal Sector Politically Different? (Null) Answers from Latin America. World Development 102: 170–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balasubramanian, Girish, and Santanu Sarkar. 2020. Organising experience of informal sector workers—A road less travelled. Employee Relations 42: 798–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barslund, Mikkel, John Rand, Finn Tarp, and Jacinto Chiconela. 2007. Understanding Victimization: The Case of Mozambique. World Development 35: 1237–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Başbay, Mustafa Metin, Ceyhun Elgin, and Orhan Torul. 2018. Socio-demographics, political attitudes and informal sector employment: A cross-country analysis. Economic Systems 42: 556–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassier, Joshua Budlender, Rocco Zizzamia, Murray Leibbrandt, and Vimal Ranchhod. 2021. Locked down and locked out: Repurposing social assistance as emergency relief to informal workers. World Development 139: 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekaj, Armend, and Lina Antara. 2018. Political Participation of Refugees: Bridging the Gaps. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance. ISBN 978-91-7671-148-4. [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, Stephen Earl, and Linda L. M. Bennett. 1986. Political participation. Annual Review of Political Science 1: 157–204. [Google Scholar]

- Benstead, Lindsay, and Ellen Lust. 2015. The Gender Gap in Political Participation in North Africa. Available online: https://www.mei.edu/ (accessed on 1 January 2022).

- Binder, Leonard. 1977. Review Essay: Political Participation and Political Development. American Journal of Sociology 83: 751–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryan, Christopher J., Gregory M. Walton, Todd Rogers, and Carol S. Dweck. 2011. Motivating Voter Turnout by Invoking the Self. Edited by Brian Skyrms. Irvine: University of California. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Andrea Louise. 2003. How Policies Make Citizens: Senior Political Activism and the American Welfare State; Princeton: Princeton University Press. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7rtmp (accessed on 29 October 2021).

- Cammett, Melani, and Isabel Kendall. 2021. Political Science Scholarship on the Middle East: A View from the Journals. PS: Political Science & Politics 54: 448–55. Available online: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/ps-political-science-and-politics/article/abs/political-science-scholarship-on-the-middle-east-a-view-from-the-journals/5F87A92D15367146DC860F651324EEE3 (accessed on 27 October 2021).

- Chen, Martha, and Jenna Harvey. 2017. The Informal Economy in Arab Nations: A Comparative Perspective, WIEGO. Available online: https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/migrated/resources/files/Informal-Economy-Arab-Countries-2017.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2021).

- Daenekindt, Stijn, Willem de Koster, and Jeroen van der Waal. 2019. Partner Politics: How Partners Are Relevant to Voting. Journal of Marriage and Family 82: 1124–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Soto, Hernando. 1989. The Other Path. New York: Harper and Row Publishers Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Delli Carpini, Michael X., Roberta S. Sigel, and Robin Snyder. 1983. Does it make any difference how you feel about your job? An empirical study of the relationship between job satisfaction and political orientation. Micropolitics 3: 227–51. [Google Scholar]

- Elbadawi, Ibrahim, and Norman Loayza. 2008. Informality, Employment and Economic Development in the Arab World. Journal of Development and Economic Policies 10: 25–75. [Google Scholar]

- Elden, J. Maxwell. 1981. Political Efficacy at Work: The Connection between More Autonomous Forms of Workplace Organization and a More Participatory Politics. American Political Science Review 75: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, Ahmed, and Jackline Wahba. 2019. Political Change and Informality. Economics of Transition and Institutional Change 27: 31–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavin, Patrick, and Michael J. Keane. 2012. Life Satisfaction and Political Participation: Evidence from the United States. Journal of Happiness Studies 13: 63–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gërxhani, Klarita. 2004. The informal sector in developed and less developed countries: A literature survey. Public Choice 120: 267–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, Donald P., and Alan S. Gerber. 2015. Get Out the Vote: How to Increase Voter Turnout. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, Alisha C., and Calla Hummel. 2022. Informalities: An Index Approach to Informal Work and Its Consequences. Latin American Politics & Society 64: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hummel, Calla. 2021. Why Informal Workers Organize: Contentious Politics, Enforcement, and the State. Oxford: Oxford Academic. Available online: https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780192847812.001.0001 (accessed on 16 September 2022).

- ILO. 2003a. Guidelines Concerning a Statistical Definition of Informal Employment. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---stat/documents/normativeinstrument/wcms_087622.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- ILO. 2003b. Statistical definition of informal employment. Paper presented at 7th International Conference of Labour Statisticians 2003, Geneva, Switzerland, November 24–December 3. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2020. Global Employment Trends for Youth 2020: Arab States. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_737672.pdf (accessed on 5 January 2021).

- ILO. 2022. Productivity Growth, Diversification and Structural Change in the Arab States. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_dialogue/---act_emp/documents/publication/wcms_840588.pdf (accessed on 25 August 2022).

- International Monetary Fund. 2020. Regional Economic Outlook—Middle East and Centra Asia. Chiyoda: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar]

- Kingston, Paul William, and Steven E. Finkel. 1987. Is There a Marriage Gap in Politics? Journal of Marriage and Family 49: 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leighley, Jan E., and Jonathan Nagler. 2013. Who votes now? In Demographics, Issues, Inequality, and Turnout in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1981. Political Man: The Social Bases for Politics. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Major, Brett C. 2018. Postcards for Virginia Study—Brief Report. Available online: https://www.brettmajor.work/project/postcards-for-virginia/ (accessed on 1 February 2022).

- Mansfield, Edward R., and Billy P. Helms. 1981. Detecting Multicollinearity. The American Statistican 36: 158–60. [Google Scholar]

- Matilla-Santander, Nuria, Emily Ahonen, Maria Albin, Sherry Baron, Mireia Bolíbar, Kim Bosmans, and Bo Burström. 2021. COVID-19 and Precarious Employment: Consequences of the Evolving Crisis. International Journal of Health Services 51: 226–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merouani, Walid, Claire El Moudden, and Nacer Eddine Hammouda. 2021. Social Security Enrollment as an Indicator of State Fragility and Legitimacy: A Field Experiment in Maghreb Countries. Social Sciences 10: 266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merouani, Walid. 2019. The Impact of Mass Media on Voting Behavior: The Cross Country Evidence. ERF Working Paper N1330. Available online: https://erf.org.eg/publications/the-impact-of-mass-media-on-voting-behavior-the-cross-country-evidence-2/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Milbrath, Lester W., and Madan Lal Goel. 1977. Political Participation. Chicago: Rand McNally. [Google Scholar]

- Morocco World News. 2021. IMF: Morocco’s Pandemic Social Protection Solutions a ‘Success Story’. Available online: https://www.moroccoworldnews.com/2020/10/323175/imf-moroccos-pandemic-social-protection-solutions-a-success-story/ (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- Nie, Norman H., G. Bingham Powell, and Kenneth Prewitt. 1969. Social Structure and Political Participation: Developmental Relationships, Part I. American Political Science Review 63: 361–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, Kim, Juliana Menasce Horowitz, Anna Brown, Richard Fry, D’vera Cohn, and Ruth Igielnik. 2018. Urban, Suburban and Rural Residents’ Views on Key Social and Political Issues. Pew Research Center Paper. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2018/05/22/urban-suburban-and-rural-residents-views-on-key-social-and-political-issues/ (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Peterson, Steven A. 1990. Political Behavior. Newbury Park: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Pop-Eleches, Cristian, Harsha Thirumurthy, James P. Habyarimana, Joshua G. Zivin, Markus P. Goldstein, Damien De Walque, Leslie Mackeen, Jessica Haberer, Sylvester Kimaiyo, John Sidle, and et al. 2011. Mobile phone technologies improve adherence to antiretroviral treatment in a resource-limited setting: A randomized controlled trial of text message reminders. AIDS 25: 825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Refaei, Mostafa Magdy. 2015. Political Participation in Egypt: Perceptions and Practice. Giza: BASEERA. [Google Scholar]

- Roth, Silke, and Clare Saunders. 2018. Gender Differences in Political Participation: Comparing Street Demonstrators in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Sociology 53: 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudra, Nita. 2002. Globalization and the Decline of the Welfare State in Less-Developed Countries. International Organization 56: 411–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharoni, Sari. 2012. e-Citizenship. Electronic Media & Politics 1: 119–35. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Friedrich. 2004. Shadow economies around the world: What do we really know? European Journal of Political Economy 21: 598–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemiatycki, Myer, and Anver Saloojee. 2003. Formal and non-formal political participation by immigrants and newcomers: Understanding the linkages and posing the questions. Canadian issue. April. Available online: https://www.proquest.com/openview/ba77d7a72ba0ee52e30893788d809af4/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=43874 (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Solati, Fariba. 2017. Women, work, and patriarchy in the Middle East and North Africa. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Teobaldelli, Désirée, and Friedrich Schneider. 2013. The Influence of Direct Democracy on the Shadow Economy. Working Paper, No. 1316. Johannes Kepler University of Linz, Department of Economics, Linz. Available online: https://www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/97439/1/770461697.pdf (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Torney-Purta, Judith, Carolyn Henry Barber, and Wendy Klandl Richardson. 2004. Trust in government related institutions and political engagement among adolescents in six countries. Acta Politica 39: 380–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thornton, Douglas S. 2000. Political attitudes and participation of informal and formal sector workers in Mexico. Comparative Political Studies 33: 1279–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNDP & ILO. 2012. Rethinking Economic Growth: Towards Productive and Inclusive Arab Societies. Geneva: ILO. [Google Scholar]

- UNESCWA. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 on Money Metric Poverty in Arab Countries. Available online: https://www.unescwa.org/publications/impact-covid-19-money-metric-poverty-arab-countries (accessed on 1 February 2021).

- Verba, Sidney, and Norman H. Nie. 1972. Participation in America: Political Democracy and Social Equality. New York: Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Welch, Susan. 1977. Women as Political Animals? A Test of Some Explanations for Male-Female Political Participation Differences. American Journal of Political Science 21: 711–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, Colin C., John Round, and Peter Rodgers. 2007. Beyond the formal/informal economy binary hierarchy. International Journal of Social Economics 34: 402–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| (Model A: Involvement) | (Model B: Participation) | (Model C: Talk Politics) | (Model D: Voting) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio | Odds Ratio |

| Informal | 0.900 | 0.705 ** | 0.740 ** | 0.740 *** |

| (0.146) | (0.0993) | (0.0919) | (0.0835) | |

| Job Satisfaction | 0.919 | 0.636 *** | 0.945 | 0.886 |

| (0.148) | (0.0859) | (0.104) | (0.0939) | |

| Male | 1.262 | 1.650 *** | 1.239 * | 1.072 |

| (0.228) | (0.268) | (0.156) | (0.129) | |

| Confident in government & political institutions | 1.546 *** | 1.616 *** | 1.263 *** | 1.656 *** |

| (0.159) | (0.148) | (0.108) | (0.137) | |

| Age | 0.995 | 0.961 ** | 1.012 | 1.180 *** |

| (0.0188) | (0.0159) | (0.0142) | (0.0173) | |

| Married | 1.566 *** | 1.146 | 1.477 *** | 1.175 |

| (0.225) | (0.144) | (0.164) | (0.122) | |

| Education | 1.230 *** | 1.070 | 1.312 *** | 1.331 *** |

| (0.0972) | (0.0715) | (0.0708) | (0.0710) | |

| 2. Employee | 0.769 * | 0.660 *** | 0.947 | 0.706 *** |

| (0.122) | (0.0901) | (0.123) | (0.0864) | |

| 3. Contributing family workers and apprentices | 0.978 | 0.739 | 1.191 | 0.732 * |

| (0.245) | (0.160) | (0.225) | (0.129) | |

| 2. Industry | 1.235 | 0.744 | 1.083 | 0.822 |

| (0.372) | (0.177) | (0.211) | (0.155) | |

| 3.Construction | 1.654 | 0.952 | 1.352 | 0.777 |

| (0.511) | (0.219) | (0.257) | (0.150) | |

| 4. Health Services | 0.889 | 0.631 | 1.705 * | 1.041 |

| (0.376) | (0.212) | (0.525) | (0.271) | |

| 5. Education sector | 1.236 | 1.342 | 1.173 | 0.590 ** |

| (0.439) | (0.379) | (0.313) | (0.150) | |

| 6. Trade | 1.034 | 0.589 ** | 1.105 | 0.616 *** |

| (0.291) | (0.126) | (0.195) | (0.110) | |

| 7. Other commercial services | 1.403 | 0.679 * | 1.690 *** | 0.737 * |

| (0.386) | (0.140) | (0.311) | (0.129) | |

| 8. Administration, non-commercial services | 0.725 | 0.573 ** | 1.222 | 0.666 ** |

| (0.242) | (0.137) | (0.262) | (0.135) | |

| Urban | 1.175 | 1.179 | 0.932 | 0.765 *** |

| (0.169) | (0.149) | (0.0996) | (0.0793) | |

| 2. Egypt | 0.739 | 0.269 *** | 0.448 *** | 2.772 *** |

| (0.202) | (0.0516) | (0.0682) | (0.411) | |

| 3. Lebanon | 3.786 *** | 0.884 | 1.515 ** | 0.279 *** |

| (0.968) | (0.140) | (0.252) | (0.0411) | |

| 4. Morocco | 5.918 *** | 2.441 *** | 0.418 *** | 0.669 ** |

| (1.545) | (0.426) | (0.0706) | (0.119) | |

| 5. Tunisia | 0.822 | 0.183 *** | 1.098 | 0.911 |

| (0.247) | (0.0422) | (0.179) | (0.135) | |

| Constant | 0.0214 *** | 1.043 | 1.122 | 0.0114 *** |

| (0.0157) | (0.650) | (0.587) | (0.00591) | |

| Observations | 2805 | 2805 | 2805 | 2805 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Merouani, W.; Jawad, R. Political Attitudes and Participation among Young Arab Workers: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Workers in Five Arab Countries. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110503

Merouani W, Jawad R. Political Attitudes and Participation among Young Arab Workers: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Workers in Five Arab Countries. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(11):503. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110503

Chicago/Turabian StyleMerouani, Walid, and Rana Jawad. 2022. "Political Attitudes and Participation among Young Arab Workers: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Workers in Five Arab Countries" Social Sciences 11, no. 11: 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110503

APA StyleMerouani, W., & Jawad, R. (2022). Political Attitudes and Participation among Young Arab Workers: A Comparison of Formal and Informal Workers in Five Arab Countries. Social Sciences, 11(11), 503. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11110503