Subjective Well-Being and Future Orientation of NEETs: Evidence from the Italian Sample of the European Social Survey

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. NEET Phenomenon in a Life-Course Approach

2.2. NEETs and Well-Being

2.3. NEETs and Future Orientation

2.4. Links between NEET Condition, Future Orientation, and Well-Being

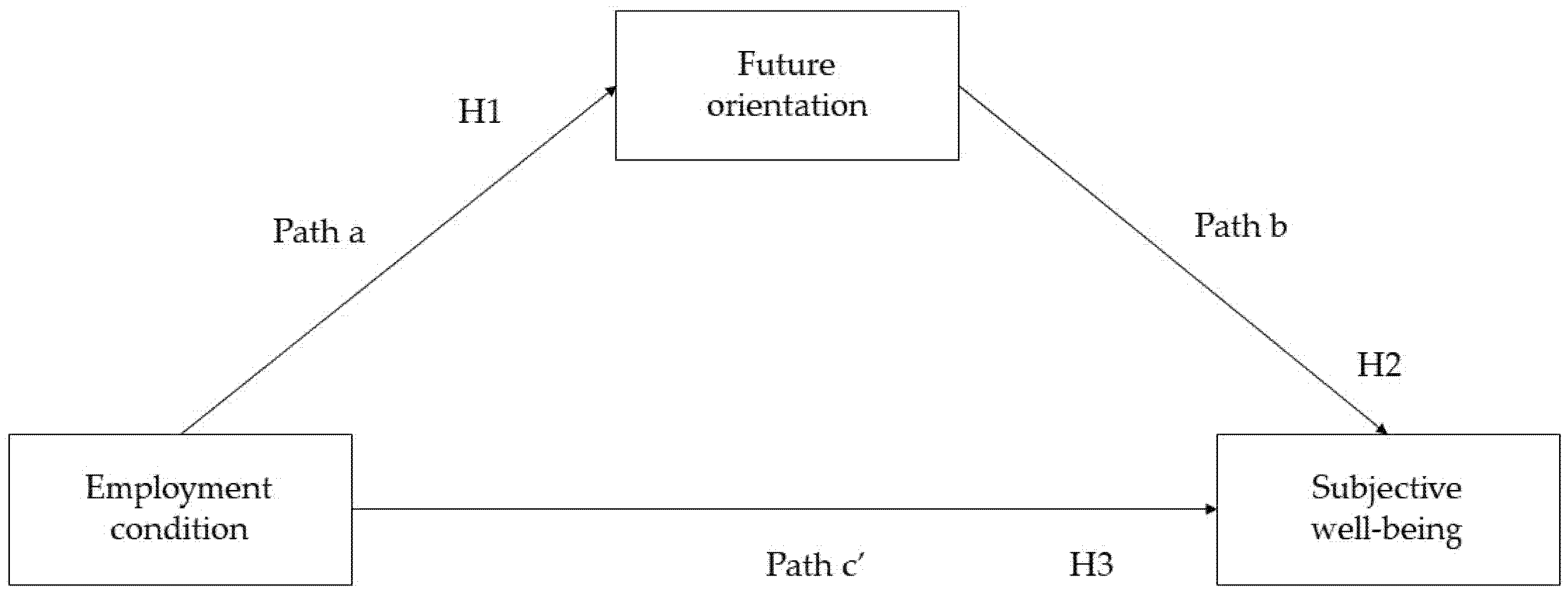

3. The Current Study

4. Materials and Methods

Data Modeling

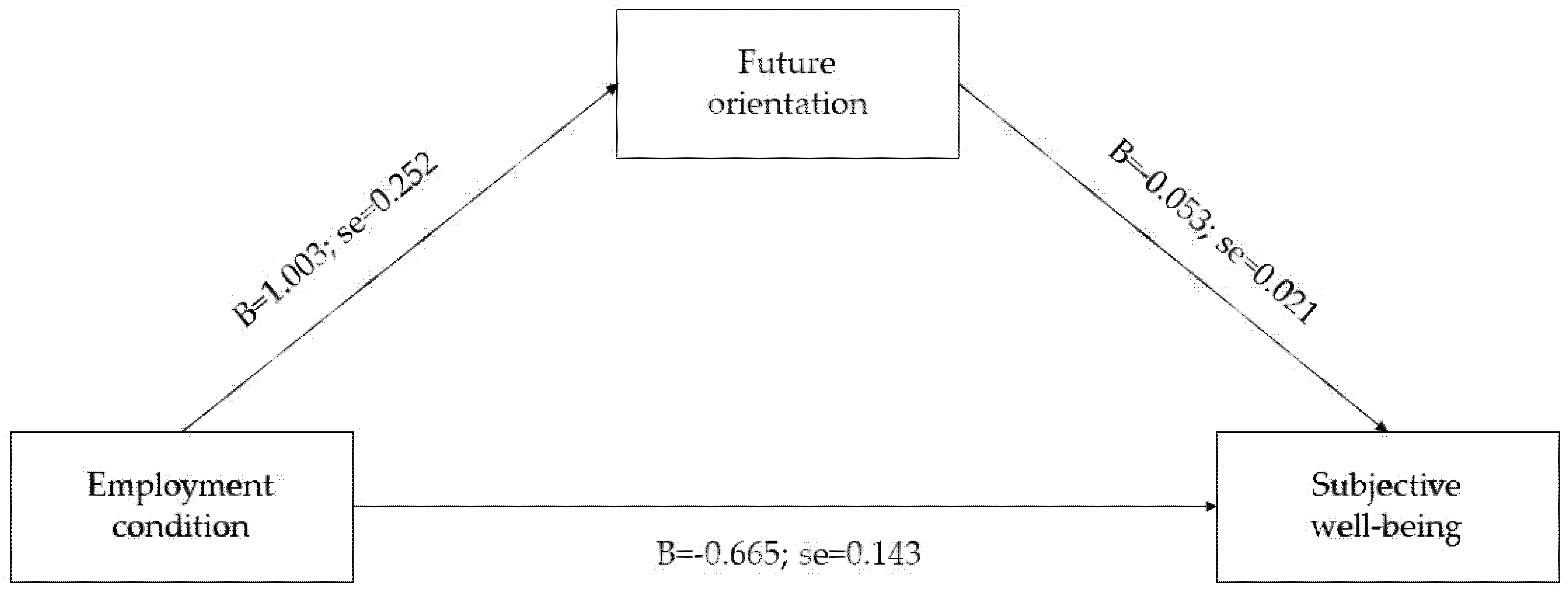

5. Results

6. Discussion

Limitations and Future Research Directions

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Avagianou, Athina, Nikos Kapitsinis, Ioannis Papageorgiou, Anna Hege Strand, and Stelios Gialis. 2022. Being NEET in youthspaces of the EU South: A post-recession regional perspective. Young 30: 11033088221086365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartelink, Vicky H. M., Kyaw Zay Ya, Karin Guldbrandsson, and Sven Bremberg. 2019. Unemployment among young people and mental health: A systematic review. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 48: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bjarnason, Thoroddur, and Thordis J. Sigurdardottir. 2003. Psychological distress during unemployment and beyond: Social support and material deprivation among youth in six northern European countries. Social Science & Medicine 56: 973–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blustein, David L., Ryan Duffy, Joaquim A. Ferreira, Valerie Cohen-Scali, Rachel Gali Cinamon, and Blake A. Allan. 2020. Unemployment in the time of COVID-19: A research agenda. Journal of Vocational Behavior 119: 103436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonanomi, Andrea, and Alessandro Rosina. 2022. Employment status and well-being: A longitudinal study on young italian people. Social Indicators Research 161: 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brannen, Julia, and Ann Nilsen. 2002. Young people’s time perspectives: From youth to adulthood. Sociology 36: 513–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunetti, Irene, and Lorenzo Corsini. 2019. School-to-work transition and vocational education: A comparison across Europe. International Journal of Manpower 8: 1411–1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchmann, Marlis C., and Irene Kriesi. 2011. Transition to adulthood in Europe. Annual Review of Sociology 37: 481–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynner, John, and Samantha Parsons. 2002. Social exclusion and the transition from school to work: The case of young people not in education, employment, or training (NEET). Journal of Vocational Behavior 60: 289–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe, Laura, and Peter Butterworth. 2016. The role of financial hardship, mastery and social support in the association between employment status and depression: Results from an Australian longitudinal cohort study. BMJ Open 6: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dastin, Jeffrey. 2018. Amazon Scraps Secret AI Recruiting Tool That Showed Bias against Women. Boca Raton: Auerbach Publications. [Google Scholar]

- De Neve, Jan-Emmanuel, Ed Diener, Louis Tay, and Cody Xuereb. 2013. The Objective Benefits of Subjective Well-Being (August 6, 2013). In World Happiness Report 2013. Edited by John Helliwell, Richard Layard and Jeffrey Sachs. New York: UN Sustainable Development Solutions Network. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2306651 (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- De Vos, Ans, Beatrice I. J. M. Van der Heijden, and Jos Akkermans. 2020. Sustainable careers: Towards a conceptual model. Journal of Vocational Behavior 117: 103196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Witte, Hans. 2005. Job insecurity: Review of the international literature on definitions, prevalence, antecedents and consequences. SA Journal of Industrial Psychology 31: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devadason, Ranji. 2008. To plan or not to plan? Young adult future orientations in two European cities. Sociology 42: 1127–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diener, Ed, Shigehiro Oishi, and Louis Tay. 2018. Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behaviour 2: 253–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diener, Ed, Derrick Wirtz, William Tov, Chu Kim-Prieto, Dong-won Choi, Shigehiro Oishi, and Robert Biswas-Diener. 2010. New Well-Being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Social Indicators Research 97: 143–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolan, Paul, Tessa Peasgood, and Mathew White. 2008. Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology 29: 94–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eurofound. 2016. Exploring the Diversity of NEETs. Eurofound. Available online: https://www.eurofound.europa.eu/de/publications/report/2016/labour-market-social-policies/exploring-the-diversity-of-neets (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Eurostat. 2022. Statistics on Young People Neither in Employment nor in Education or Training. Statistics Explained. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Statistics_on_young_people_neither_in_employment_nor_in_education_or_training (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Felaco, Cristiano, and Anna Parola. 2020. Young in university-work transition: The views of undergraduates in southern Italy. The Qualitative Report 25: 3129–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, Martin. 2015. Rise of the Robots: Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Victor R., ed. 1982. Time preference and health: An exploratory study. In Economic Aspects of Health. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, pp. 93–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fusco, Luca, Anna Parola, and Luigia Simona Sica. 2021. Life design for youth as a creativity-based intervention for transforming a challenging World. Frontiers in Psychology 12: 662072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fusco, Luca, Luigia Simona Sica, Anna Parola, and Laura Aleni Sestito. 2022. Vocational identity flexibility and psychosocial functioning in Italian high school students. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 10: 144–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gariépy, Geneviève, Sofia M. Danna, Lisa Hawke, Johanna Henderson, and Srividya N. Iyer. 2021. The mental health of young people who are not in education, employment, or training: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 57: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaspani, Fabio. 2018. Young-adults NEET in Italy: Orientations and strategies toward the future. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy 38: 150–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ginevra, Maria Cristina, Susanna Pallini, Giovanni Maria Vecchio, Laura Nota, and Salvatore Soresi. 2016. Future orientation and attitudes mediate career adaptability and decidedness. Journal of Vocational Behavior 95: 102–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman-Mellor, Sidra, Avshalom Caspi, Louise Arseneault, Nifemi Ajala, Antony Ambler, Andrea Danese, Helen Fisher, Abigail Hucker, Candice Odgers, Teresa Williams, and et al. 2016. Committed to work but vulnerable: Self-perceptions and mental health in NEET 18-year olds from a contemporary British cohort. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57: 196–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guthrie, Lori C., Stephen C. Butler, and Michael M. Ward. 2009. Time perspective and socioeconomic status: A link to socioeconomic disparities in health? Social Science & Medicine 68: 2145–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutierrez-Garcia, Raúl A., Corina Benjet, Guilherme Borges, Enrique Méndez Rios, and Maria Elena Medina-Mora. 2017. NEET adolescents grown up: Eight-year longitudinal follow-up of education, employment and mental health from adolescence to early adulthood in Mexico City. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 26: 1459–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartung, Paul J. 2019. Life design: A paradigm for innovating career counselling in global context. In Handbook of Innovative Career Counselling. Cham: Springer, pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, Jeff, and Sandra Blakeslee. 2004. On Intelligence. New York: Times Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, Andrew F. 2017. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Iannone, R. 2018. DiagrammeR: Graph/Network Visualization. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DiagrammeR (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- International Labor Organization World Employment and Social Outlook—Trends. 2020. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/research/global-reports/weso/2020/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 1 September 2022).

- Johnson, Monica Kirkpatrick, Rober Crosnoe, and Glen H. Elder, Jr. 2011. Insights on adolescence from a life course perspective. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21: 273–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jongbloed, Janine, and Jean-François Giret. 2022. Quality of life of NEET youth in comparative perspective: Subjective well-being during the transition to adulthood. Journal of Youth Studies 25: 321–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, Sonia, Katherine DeCelles, András Tilcsik, and Sora Jun. 2016. Whitened Résumés: Race and self-presentation in the labor market. Administrative Science Quarterly 61: 469–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooij, Dorien T. A. M., Ruth Kanfer, Matt Betts, and Cort W. Rudolph. 2018. Future Time Perspective: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 103: 867–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotroyannos, Dimitrios, Kostas A. Lavdas, Nikos Papadakis, Argyris Kyridis, Panagiotis Theodirikakos, Stylianos Ioannis Tzagkarakis, and Maria Drakaki. 2015. An individuality in parenthesis? social vulnerability, youth and the welfare state in crisis: On the case of neets, In Greece, within the European context. Studies in Social Sciences and Humanities 3: 268–79. [Google Scholar]

- López-López, José A., Alex S. F. Kwong, Elizabeth Washbrook, Rebecca M. Pearson, Kate Tilling, Mina S. Fazel, Judy Kidger, and Gemma Hammerton. 2019. Trajectories of depressive symptoms and adult educational and employment outcomes. BJPsych Open 6: e6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacKinnon, David P. 2012. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Manhica, Helio, Andreas Lundin, and Anna-Karin Danielsson. 2019. Not in education, employment, or training (NEET) and risk of alcohol use disorder: A nationwide register-linkage study with 485 839 Swedish youths. BMJ Open 9: e032888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascherini, Massimiliano. 2019. Origins and future of the concept of NEETs in the European policy agenda. In Youth Labor in Transition. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 503–29. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed, Susan, and Jacqueline T. Marhefka. 2020. How have we, do we, and will we measure time perspective? A review of methodological and measurement issues. Journal of Organizational Behavior 41: 276–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, Pen, Wanglin Ma, and Alfonso Sousa-Poza. 2021. The relationship between smartphone use and subjective well-being in rural China. Electronic Commerce Research 21: 983–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurmi, Jari-Erik. 2005. Thinking about and acting upon the future: Development of future orientation across the life span. In Understanding Behavior in the Context of Time: Theory, Research, and Application. Edited by Alan Stratham and Jeff Joireman. Mahwah: Erlbaum, pp. 31–57. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dea, Bridianne, Rico S. C. Lee, Patrick D. McGorry, Ian B. Hickie, Jan Scott, Daniel F. Hermens, Harnestein Mykeltun, Rosemary Purcell, Eoin Killackey, Christos Pantelis, and et al. 2016. A prospective cohort study of depression course, functional disability, and NEET status in help-seeking young adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 51: 1395–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parola, Anna, and Lucia Donsì. 2019. Time perspective and employment status: NEET categories as negative predictor of future. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 7: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, Anna, and Jenny Marcionetti. 2022. Youth unemployment and health outcomes: The moderation role of the future time perspective. International Journal for Educational and Vocational Guidance 22: 327–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parola, Anna, Jenny Marcionetti, Luigia Simona Sica, and Lucia Donsì. 2022. The effects of a non-adaptive school-to-work transition on transition to adulthood, time perspective and internalizing and externalizing problems. Current Psychology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, Francesco. 2019. Why so slow? The school-to-work transition in Italy. Studies in Higher Education 44: 1358–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pastore, Francesco, Claudio Quintano, and Antonella Rocca. 2022. The duration of the school-to-work transition in Italy and in other European countries: A flexible baseline hazard interpretation. International Journal of Manpower. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piumatti, Giovanni, Laura Pipitone, Angela Maria Di Vita, Delia Latina, and Emanuela Rabaglietti. 2014. Transition to adulthood across Italy: A comparison between Northern and Southern Italian young adults. Journal of Adult Development 21: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, Emmet, Mary Clarke, Ian Kelleher, Helen Coughlan, Fionnuala Lynch, Dearbhla Connor, Carol Fitzpatrick, Michelle Harley, and Mary Cannon. 2015. The association between economic inactivity and mental health among young people: A longitudinal study of young adults who are not in employment, education or training. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine 32: 155–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prenda, Kimberly M., and Margie E. Lachman. 2001. Planning for the future: A life management strategy for increasing control and life satisfaction in adulthood. Psychology and Aging 16: 206–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. 2017. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- Raffe, David. 2008. The concept of transition system. Journal of Education and Work 21: 277–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffe, David. 2014. Explaining national differences in education-work transitions: Twenty years of research on transition systems. European Societies 16: 175–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodwell, Laura, Helena Romaniuk, Wendy Nilsen, John B. Carlin, KJ Lee, and George Christopher Patton. 2018. Adolescent mental health and behavioural predictors of being NEET: A prospective study of young adults not in employment, education, or training. Psychological Medicine 48: 861–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Yves, Terrence D. Jorgensen, Nicholas Rockwood, Daniel Oberski, Jarett Byrnes, Leonard Vanbrabant, Victoria Savalei, Ed Merkle, Michael Hallquist, Mijke Rhemtulla, and et al. 2015. Package “lavaan”: Latent Variable Analysis. Madison: R Package. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, Alessandro Alberto, Maria Marconi, Federica Taccini, Claudio Verusio, and Stefania Mannarini. 2021. From Fear to Hopelessness: The Buffering Effect of Patient-Centered Communication in a Sample of Oncological Patients during COVID-19. Behavioral Sciences 11: 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savickas, Mark L. 2012. Life design: A paradigm for career intervention in the 21st century. Journal of Counseling & Development 90: 13–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schimmack, Ulrich. 2006. Internal and external determinants of subjective well-being: Review and policy implications. In Happiness and Public Policy: Theory, Case Studies and Implications. Edited by Yew-Kwang Ng and Lok Sang Ho. New York: Palgrave McMillan, pp. 67–88. [Google Scholar]

- Schnaudt, Christian, Michael Weinhardt, Rory Fitzgerald, and Stefan Liebig. 2014. The European Social Survey: Contents, design, and research potential. Journal of Contextual Economics: Schmollers Jahrbuch 134: 487–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoon, Ingrid, and John Bynner, eds. 2017. Young People’s Development and the Great Recession: Uncertain Transitions and Precarious Futures. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Schoon, Ingrid, and John Bynner. 2019. Young people and the Great Recession: Variations in the school-to-work transition in Europe and the United States. Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 10: 153–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seginer, Rachel. 2009. Future Orientation: Developmental and Ecological Perspectives. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shanahan, Michael J. 2000. Pathways to adulthood in changing societies: Variability and mechanisms in life course perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, Michael J., Jeylan T. Mortimer, and Monica Kirkpatrick-Johnson, eds. 2016. Handbook of the Life Course, Volume II. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Shipp, Abbie J., Jeffrey R. Edwards, and Lisa S. Lambert. 2009. Conceptualization and measurement of temporal focus: The subjective experience of the past, present, and future. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 110: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh-Manoux, Archana, and Michael Marmot. 2005. Role of socialization in explaining social inequalities in health. Social Science & Medicine 60: 2129–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobol-Kwapinska, Malgorzata, Tomasz Jankowski, and Aneta Przepiorka. 2016. What do we gain by adding time perspective to mindfulness? Carpe Diem and mindfulness in a temporal framework. Personality and Individual Differences 93: 112–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stea, Tonje H., Eirik Abildsnes, Arve Strandheim, and Siri H. Haugland. 2019. Do young people who are not in education, employment or training (NEET) have more health problems than their peers? A cross-sectional study among Norwegian adolescents. Norsk Epidemiologi 28: 89–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Rachel C. F., and Daniel T. Shek. 2012. Beliefs in the future as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutin, Angelina R., and Paul T. Costa, Jr. 2010. Reciprocal influences of personality and job characteristics across middle adulthood. Journal of Personality 78: 257–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, Pekka, Anne Hammarström, and Urban Janlert. 2016. Children of boom and recession and the scars to the mental health—A comparative study on the long-term effects of youth unemployment. International Journal for Equity in Health 15: 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walther, Andreas. 2006. Regimes of youth transitions: Choice, fexibility and security in young people’s experiences across different European contexts. Young 14: 119–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Taiyun, Vilian Simko, Michael Levy, Yihui Xie, Yan Jin, and Jeff Zemla. 2017. Package ‘corrplot’. Statistician 56: e24. [Google Scholar]

- Weston, Sara J., Stuart J. Ritchie, Julia M. Rohrer, and Andrew K. Przybylski. 2019. Recommendations for increasing the transparency of analysis of preexisting data sets. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science 2: 214–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaleski, Zbigniew, Malgorzata Sobol-Kwapinska, Aneta Przepiorka, and Michal Meisner. 2019. Development and validation of the Dark Future scale. Time & Society 28: 107–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Hongyun, and Wanglin Ma. 2021. Click it and buy happiness: Does online shopping improve subjective well-being of rural residents in China? Applied Economics 53: 4192–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimbardo, Philip G., and John N. Boyd. 1999. Putting Time in Perspective: A Valid, Reliable Individual-Differences Metric. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 77: 1271–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuccotti, Carolina V., and Jacqueline O’Reilly. 2019. Ethnicity, gender and household effects on becoming NEET: An intersectional analysis. Work, Employment and Society 33: 351–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Attributes | n (%)/M (SD) | Sk./K. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female Male | 343 (50.6) 352 (49.4) | |

| Marital status | Married/civil union Separated/divorced None of these | 103 (14.9) 9 (1.3) 579 (83.8) | |

| Years of education | 13.20 (3.383) | 0.314/0.118 | |

| Age | 24.72 (5.931) | 0.105/−1.156 | |

| Employment condition | Non-NEET NEET | 153 (22.2) 535 (77.8) | |

| Income source | Employment Others None | 276 (43.6) 19 (3.7) 319 (52.7) | |

| Residence area | Large cities and surroundings Medium cities and towns Countryside | 129 (18.6) 237 (34.2) 326 (47.1) |

| Non-NEET | NEET | t-Test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) [95% CI] | M (SD) [95% CI] | T(df) | 95% CI | g | Sk./K. | |

| Well-being | 7.496 (1.400) [7.376,7.610] | 6.778 (1.992) [6.458,7.082] | 5.050 * (685) | [0.439,0.998] | 0.417 | −1.027/ 1.585 |

| Future orientation | 4.58 (2.696) [4.36,4.81] | 5.58 (2.939) [5.12,6.05] | −3.975 * (685) | [0.379,1.058] | 0.465 | 0.214/ −0.737 |

| B | se | 95% CI[L-U] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Path a | 1.003 | 0.252 | [0.508; 1.495] |

| Path b | −0.053 | 0.021 | [−0.095; −0.011] |

| Path c’ | −0.665 | 0.143 | [−0.947; −0.384] |

| Indirect effect | −0.053 | 0.029 | [−0.116; −0.005] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Felaco, C.; Parola, A. Subjective Well-Being and Future Orientation of NEETs: Evidence from the Italian Sample of the European Social Survey. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100482

Felaco C, Parola A. Subjective Well-Being and Future Orientation of NEETs: Evidence from the Italian Sample of the European Social Survey. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(10):482. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100482

Chicago/Turabian StyleFelaco, Cristiano, and Anna Parola. 2022. "Subjective Well-Being and Future Orientation of NEETs: Evidence from the Italian Sample of the European Social Survey" Social Sciences 11, no. 10: 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100482

APA StyleFelaco, C., & Parola, A. (2022). Subjective Well-Being and Future Orientation of NEETs: Evidence from the Italian Sample of the European Social Survey. Social Sciences, 11(10), 482. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11100482