Abstract

The paper addresses political issues related to policy interventions for food system sustainability. It presents the results of a literature review, which explores how the concept of power has been used so far by scholars of food system dynamics. Articles numbering 116 were subjected to an in-depth qualitative analysis, which allowed the identification of three main strands of the literature with respect to food and power issues: (1) marketing and industrial organisation literature, dealing with the economic power exercised by economic actors in contexts of noncompetitive market structures; (2) articles addressing the power issue from a political economy perspective and by using an interdisciplinary approach; (3) heterogenous studies. The results of the review witness a growing interest for the analysis of food systems, political issues, and the need of a wider use of analytical tools and concepts offered by social sciences for the study of power in sustainability policy design.

1. Introduction

The three dimensions of sustainability (environmental, economic, and social) per se entail equity and trade-off dilemmas in policy makers’ decision processes; therefore, there is a strong need for political, besides economic and technological, considerations. When evaluating alternative policies, the criteria of effectiveness and efficiency are used in the first place and equity is used in the second place. While the analysis of policies in terms of equity refers to considerations of a political nature that often use the concept of power, the latter is very rarely used when the analysis concerns the criteria of efficiency and effectiveness.

The literature on sustainability has mainly conceptualized power in the context of sustainability transitions and transition governance, focusing on the issue of empowerment and transformative agencies (Avelino 2017). Less attention, instead, has been focused on the analysis of the multiple and conflicting roles that states play in transitions (Johnstone and Newell 2018). With respect to the food system, there is a longstanding tradition of political economy studies, which has been mainly used to address the intertwined topics of food security, trade policies, development, and international relations. Research in this field has mainly followed two strains: the liberal approach enriched with the human-right-based theories of Nussbaum and Sen (1993) and the critical approach of food regime studies (Friedmann 1987). Stemming from the 1990s, other topics such as food governance, self-regulation, and corporate power have been approached from a political economy stance (Clapp and Fuchs 2009), and the specific topic of food sustainability has also recently been taken into account (Béné 2022; Duncan et al. 2019; Leach et al. 2020).

This paper explores the concept of power as a further instrument that is useful for addressing the topic of food systems’ sustainability. A tenet of the paper is that the concept of power may help address sustainability-related political issues, facilitating the resolution of various conflicts inherent the interventions for sustainability and leading to more democratic and effective choices. The research question addressed by the article is as follows: to what extent has the literature on food system sustainability used theories of power developed from different social sciences so far?

In order to answer such a question, we carried out a literature review that is aimed at providing examples of how power has been so far taken into account by the relevant literature on food system sustainability. The proposed articles were grouped with respect to the addressed topics in order to identify the main strains of research on power in the food system.

The paper is organized as follows. The first section recalls the main theories on power developed in the field of social sciences. The second and the third sections present, respectively, the methodology and the results of the literature review. The concluding section points out some limitations of the study and offers suggestions for future research studies. The general result of our research indicates that although some popular sustainability issues may greatly take advantage of the use of the concept of power, there is still a gap between the potential inherent concept of power and its actual use in food sustainability studies. As a consequence, there is plenty of room for the development of this research field, and we hope that our work will be a useful, albeit modest, contribution to it.

2. Theories of Power

As generally stated in the relevant literature, power is a contested concept. Since power is everywhere and manifests itself in so many different forms, it risks being an overused concept that is often trivialized by social scientists besides other people. Notwithstanding the difficulties in finding rigorous definitions of power, power studies have hit the mark in many social sciences such that we currently have some robust and viable theories of power.

The concept of power has been discussed and elaborated mostly within social and political theory. Haugaard’s classic book (Haugaard 2002) reconstructs in a very comprehensive way the evolution of the different theories of power within political theory and sociology. Haugaard identifies three main theoretical strands. The first, within the analytical political theory rooted in Russell’ work, begins with the definition of power given by Dahl (1957, 1986) in the 1950s. It is developed with the milestone works of Bachrach and Baratz (1962) and Lukes (1974, 2005) and reaches a more complex analytical and philosophical evolution with the works of Dowding (1996) and Morriss (2002). The second strand, born from the two main founders of modern sociological theory (Weber and Marx), includes the theories of power developed within the main theories of social action of the twentieth century and particularly in Parsons’ Functionalism, Giddens’ theory of Structuration, Luhman’s Communication Theory, and Bourdieu’s Field Theory. Haugaard’s own contribution (Haugaard 1997) and Gaventa’s work (Gaventa 1982) also belong to this latter line of power studies. The third strand, inscribed within postmodern social thought, revolves around the concept of power developed by Foucault, with influences also from Laclau and Mouffe’s Theory of Discourse, and led to outstanding works in the field, such as Clegg’s theory of circuits of power. Together with these three strands, Haugaard also quotes Arendt’s own understanding of power, which he inscribes in the tradition of nonanalytical political theory.

Notwithstanding the complexity and variety of approaches that have been used by social scientists to build power theories, it is nevertheless possible to resume some widely accepted definitions and theories useful to address policy issues also in the field of sustainability. In particular, there are two widely used methods to classify power, with one concerning the distinction between power over and power to (Pansardi 2012) and one concerning the distinction among the so-called three faces of power.

Power over refers to the classical definition proposed by Dahl, according to which “A has power over B to the extent that he can get B to do something that B would not otherwise do” (Dahl 1957, p. 202). Power over identifies power as a relational concept describing a causal relation (A causes B to do something). It can account for relations of domination, influence, and paternalism. Domination occurs when B does something that negatively affects her/himself; influence occurs when B is induced to do something that she/he would not resist and that does not negatively affect her/himself; paternalism means that B does something that she/he would resist but that is “supposed to” positively affect her/himself. As regards the means by which power over may be exercised, these include the following: threats, rewards, and persuasion. Power to refers to the ability of a social actor to carry out something, that is, to bring about outcomes. Dowding’s definition of power over and power to as “social power” and “outcome power” well clarifies the distinction between the two forms of power. The term empowerment is used to refer to a narrower definition of power to, intended as “the power to act” acquired by individuals in subordinate groups despite their subordination (Allen 2018). When power to as empowerment is exercised by more than one actor in a cooperative manner, the term power with is used.

The three faces of power refer to a famous characterization of the concept of power, developed in the 1960s and 1970s within the community power debate and which identifies the three dimensions of power. The first dimension is the form of relational power developed in the wake of Dahl’s definition within traditional liberal political thought. The second dimension, firstly introduced by Bachrach and Baratz (1962), is “agenda power”, which refers to the power decision makers have not only to choose among “choices on the table” (first face of power) but also to leave some possible choices off the table, excluding them from the political agenda. The third dimension, sometimes called hegemonic power, is Lukes’s (1974) radical view of power, which “maintains that people’s wants may themselves be a product of a system which works against their interests, and, in such cases, relates the latter to what they would want and prefer, were they able to make the choice” (Lukes 2005, p. 49). In other words, it is the ability to manipulate others desires: “Such a power occurs when subordinates remain unaware of their true interests as a result of mystification, repression, or the sheer unavailability of alternative ideological frames” (Lukes 2005, p. 10).

In the field of economics, which was excluded in Haugaard’s book, we can broadly identify two main lines of research that have focused on the theme of power. The first concerns the theories of market imperfection; the second concerns the theory of the firm and contract theories within a neo-institutionalist approach (Sodano 2006). On the sidelines of these strands, there are some contributions, with less clear-cut outlines, in the more variegated fields of research on institutionalism, economic sociology, and business and administrative science.

Neoclassical economics in its purest form quotes only one form of power, the purchasing power, which is an exogenous variable included in the budget constraint that delimits the problem of utility maximization in the consumer theory. It is only with the introduction of the analysis of non-competitive market equilibria, initiated in 1933 with the two seminal works of Robinson (1933) and Chamberlin (1933), that power, in the form of market power, becomes an endogenous variable in the standard economic theory. Following the development of non-competitive market equilibria, two forms of power have been added: buying power and countervailing power, in the context of monopsonistic markets, and bargaining power, in the context of bilateral monopoly. While market and buying power can still be accounted for within the boundaries of market equilibrium analysis of the standard model, bargaining power and countervailing power give rise to theoretical problems that undermine the cleanness and the formal rigor of the standard model at its roots. In a bilateral monopoly, the buyer and seller maximize their profit independently by setting different prices, and an equilibrium cannot be reached. Consequently, not considering the case of vertical integration and exchange failure, the parties are forced to negotiate a price and a quantity. Where the solution ends up dependent on the way in which the negotiating process occurs and on the relative bargaining power of each side. One of the most used model by economists is the Nash bargaining model, which, given its axiomatic approach, can be, with a good set of hypotesis, integrated in econometric models of market equilibria. Nevertheless, such models (Bonnet and Bouamra-Mechemache 2016; Bonnet et al. 2022) often consider bargaining power as an exogenous parameter and, therefore, do not directly address the role of power in negotiations. Non-cooperative bargaining models, subsequent to the Nash model, cover situations that do not necessarily satisfy the Nash bargaining axioms and are mainly grounded on the Rubinstein bargaining model with alternating offers (Rubinstein 1982). Many non-cooperative bargaining models, nevertheless, leave the problem of indeterminacy in bilateral monopoly unsolved. The problem of indeterminacy in bilateral monopoly has also been addressed using the power-dependence theory (Cook and Emerson 1978) within the social network analysis. The power-dependence theory states that the efficient and equitable bargaining solution of a dyadic exchange (i.e., the equal distribution of the total maximum exchange value) occurs when no parties have alternative sources and when the behavior is driven by normative concerns about equity (i.e., the parties will refuse any outcome that unequally distributes the total profit, in the same manner as in the ultimatum game in which the responder will refuse low offers). When one agent has alternative sources and equity concerns are weak, the exchange outcome will be chosen by the agent with more power, with the power associated with the position of the agents in the network, i.e., with the number of alternative available sources.

The theory of the firm inscribed within neo-institutionalism explicitly underlines the importance of power for economic organisation. In a sense, New Institutional Economics can be considered as an enlargement of the standard model that takes the power issue explicitly into account. The famous Robertson’s definition of firms as “islands of conscious power in this ocean of unconscious cooperation like lumps of butter coagulating in a pail of buttermilk” was used by Coase (1937) to launch the question of how it is that, in capitalist economies, firms (and thus power) substitute the market as a means to allocate resources (Rajan and Zingales 1998). Williamson’s Transaction Costs Theory (Williamson 1985), the property rights approach to the theory of firms (Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart and John 1990), and the theory of contracts in general place power at the center of economic analysis into two ways: 1. They recognize firms as hierarchies, i.e., as organisations where power (in forms of command on resource allocation) is the ultimate economic organisational medium (instead of markets); 2. they recognize that contract incompleteness is an organisational driver in the economic system and that the study of contract incompleteness entails the study of power. This is because power may correct contract incompleteness in two ways: as bargaining power for the appropriation of quasi-rents and residual property claims; as institutional power influencing the possibility of effective enforcement mechanisms, in this latter case demonstrating that a low level of enforcement explains how “even in competitive equilibrium, a market economy sustains a system of power relations” (Bowles and Gintis 1998).

A further recurring term in economic policy studies is corporate power. While it is widely accepted as common sense that corporations have the power to influence social, economic, and political life, social science scholars have not yet developed a specific theory of corporate power. As an example, in his literature review, Neil Rollings (2021) notices that “notwithstanding business power is a relevant concept to much existing business history research, power is dealt with implicitly and indirectly in the majority of this historiography, if it is dealt with at all”.

In conclusion of this brief review on the definitions of power, it is worth remembering that power (be it overt or covert and actual or latent of a single individual or of an organisation) must necessarily be based on the access to a set of resources able to feed such power (sources of power). These resources are numerous: economic, technological, information, knowledge-based (human capital), and organisational (including social capital and the position of formal authority within organisations). While such resources are necessary to exercise power, sometimes they are not sufficient. They need to be supported by other sources of power, such as the following: nonformal institutions, such as cultural norms giving some individuals more authority; structural power (i.e., according to social network analysis, depending on the node of the social network occupied by the individual); or residing in the “power-endowment” (or the “atouts” endowment, according to the terminology of Crozier and Friedberg (1977) of the powerful actor.

3. The Literature Review: Methodology

The goal of the literature review was to understand how the concept of power has been used so far to depict food system dynamics. Consistently with the Prisma statement, our methodology included a search strategy and selection process, data collection process, synthesis method, study characterization, and a report of results (Page et al. 2021; Snyder 2019). In order to produce a general interpretation of the results, we chose a semi-systematic approach designed for topics, such as the one we wanted to explore, that are conceptualized differently and that are studied by researchers from diverse disciplines (Wong et al. 2013).

Our information source was the Scopus bibliographical database. The Scopus database is a large database of abstracts and citations, and it is widely recognized as a trustworthy database for academic research. In addition, among the large databases of abstracts and citations, Scopus shows the best international and regional coverage of academic journals and books about social sciences and economic sciences (Pranckutė 2021).

The Scopus database was queried by performing an advanced search that allows making search queries using field codes and Boolean operators to narrow the scope of the search (search strategy). The search was carried out using a field code called Author Keywords, showing the keywords assigned to the document by the author. The terms used in Author Keywords were combined using the Boolean operator “and” to select documents that include the chosen terms even if they may be distant from each other (selection process). The search focused on the two words, “power” and “food”, using the following key search term: autkey (power and food). We chose to restrict our search only to the keywords, without considering titles and abstracts, in order to select publications that presumably recognize power as an individual analytical concept (eligibility criteria). No time, subject area, or language restrictions were imposed. The Scopus database was searched on 31 March 2022.

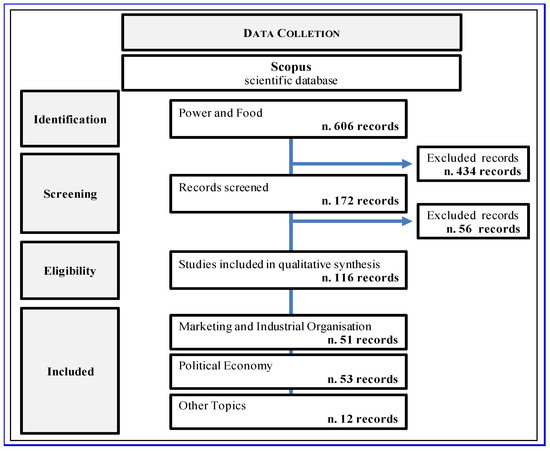

At the end of the data collection process, the search results included 606 records, with coverage years ranging from 1981 to the first quarter of 2022 (Figure 1). Title, abstract, author keywords, and general keywords of each study were kept in our database. After that, author keywords, general keywords, and abstract were screened for all records in order to check for their eligibility. We excluded all articles where the word power referred to energy sectors, reducing the sample to 172 records. For these 172 records, full texts were retrieved, reviewed, and tabulated by authors. After a full-text reading, a second eligibility check was performed. We scrutinized the downloaded articles and only retained items where the word power was used in the context of economics and political economy, excluding articles referring to other issues that generally were in the field of history. As result of the eligibility check, 116 articles were included in the review (study selection).

Figure 1.

Methodological design of bibliometric analysis.

All 116 articles were subjected to an in-depth qualitative analysis by using deductive coding that is useful for a systematic presentation of study characteristics and a synthesis of their findings. They were split into three main groups, which are named as follows: Marketing and Industrial Organisation (51 articles); Political Economy (53 articles); Others (12 articles).

The first group of Marketing and Industrial Organisation articles deals with the economic power exercised by economic actors in contexts of noncompetitive market structures, such as monopoly/oligopoly, monopsony/oligopsony, and bilateral monopoly. They use theories and models from industrial organisations, including new empirical industrial organisation, game theory, and management science.

Articles in the second group (Political Economy) address the power issue from a political economy perspective and exhibit a certain degree of interdisciplinarity, using concepts and perspectives, besides political economy, from politics, sociology, and economic institutionalism.

The group Others includes heterogenous studies that generally focused on specific power contexts, such as soft power in culinary diplomacy or technological innovation power-related issues.

4. The Literature Review: Results

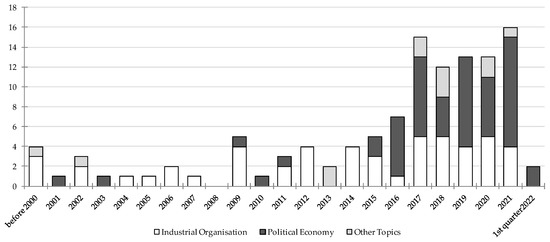

Selected articles for the in-depth qualitative analysis cover the years ranging from 1992 to 2022. As shown in Figure 2, articles published for each year are a small number (modal value 16). Since 2016, the number of articles published for each year significantly increased, with the total number published over the last 6 years being two and a half times (83 articles) the total number of articles published in the previous 25 years (33 articles). Descriptive analysis showed that power related to economic issues is an old research topic that has received renewed attention over the 6 past years. Figure 2 shows that Marketing and Industrial Organisation articles are steadily present over the years, while the studies responsible for the renewed attention over the past 6 years are mainly included in the Political Economy (48 studies) and Others (8 publications) groups.

Figure 2.

Included studies (116 records)—year of publication and main topics.

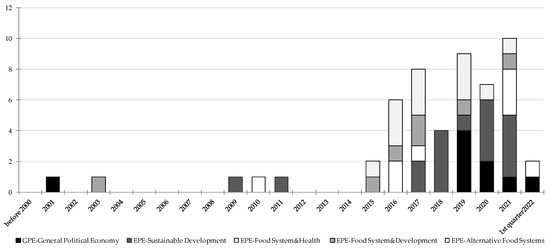

Within the Political Economy group, we distinguished articles with a more general theorical imprint (the General Political Economy group, made of 9 articles) from those referring mainly to empirical research and case studies (the Empirical Political Economy group, made of 44 articles). Within this latter group, four main groups were identified relating to the following topics: sustainable development (17 articles); relationship between food system and health (8 articles); relationship between food security, development and food sovereignty (7 articles); alternative food systems/networks (12 articles). Figure 3 shows the time series of the Political Economy group. All articles were published in recent years, with articles referring to sustainable development and alternative food systems being the most numerous. Articles included in the General Political Economy group were almost all published in recent years (after 2018), witnessing the efforts made to analyze power issues from a broader theoretical perspective.

Figure 3.

Group of Political Economy studies (53 records)—year of publication and main topics.

Table 1 summarizes the proposed classification of the selected articles and reports the articles that explicitly refer to the theories of power mentioned in the second paragraph for each group. It is worth noticing that only 16 out of the analyzed 116 articles contain references to the literature on the theory of power, with quotations of power scholars and/or theoretical approaches. About one-third of these 16 articles belong to the General Political Economy group (5 out of 16). Next, paragraphs present some of the main issues dealt with by the selected articles.

Table 1.

Articles with references to the literature on the theory of power (16 records)—chronological order in descending order.

4.1. Industrial Organisation and Marketing

In the Industrial Organisation and Marketing group, we included the articles that deal with the power exercised in the economic sphere as described mainly by orthodox economic theories and classical management theories. Some of the articles in this group limit their scope to assessing the power exercised by large corporations in terms of market power and the associated effects on consumer welfare, using either classic concentration indexes or econometric models, also framed in a game theory language, introduced by the New Empirical Industrial Organization (Aalto-Setälä 2002; Assefa et al. 2017; Bhuyan and Lopez 1997; Cacchiarelli and Sorrentino 2018; Dai et al. 2018; Hirsch and Koppenberg 2020; Jensen 2009; Kufel-Gajda 2017; Lloyd 2017; Lloyd et al. 2009; Lopez et al. 2018, 2002; Loy et al. 2016; Ma et al. 2019; Rezitis and Kalantzi 2012; Sigarev et al. 2018; Zago and Pick 2004; Wilhelmsson 2006). These articles may be considered as a response by very orthodox economics to the concerns raised by many sectors of society on the dramatic processes of consolidation that occurred in the 1980s and 1990s, which first brought to the fore the issue of power within the food system. Using the econometric models of the New Empirical Industrial Organization, they maintain, in quite intact manner, the full theoretical apparatus of mainstream economics based on the Rational Choice Theory and on the concept of a firm as a production function. Such an attitude is also coherent with their endorsement of the shift of antitrust authorities, which occurred in United States of America and European Union in the late 1970s from the Harvard school to the Chicago school perspective. According to the Chicago School, the aim of an antitrust policy is not to guarantee people’s rights against unwanted and uncontrolled exercise of power by corporate actors anymore but instead to achieve economic efficiency; consequently, it dismisses the dimension of power in antitrust policies (Sodano 2010).

Other articles extend their theoretical armamentarium to include tools from business and management theory. Many of these articles analyze the consequences of consolidation processes not only in terms of efficiency and consumers’ loss but also in terms of distributive effects along the food supply chain. Here, the focus is on the issue of power imbalances characterizing relationships in vertical supply chains. Previous studies use aggregate data to asses buying power with classical approaches from industrial organisation (Barros et al. 2006; Bonanno and Lopez 2009; Connor et al. 1996; Marfels 1992). Later studies investigate actual firms’ strategies by using case studies and qualitative research methods, which allow for the use of a wider spectra of approaches and perspectives of power analysis. Here, the focus on the value-added distribution, besides the efficiency issue, politicizes the analysis, calling for a state intervention (such as minimum wages or fairer taxation) based on social justice besides economic goals (Fałkowski et al. 2017; He 2021; Sejak 2009; Seok and Kim 2020). Some articles, by suggesting forms of collaboration for countervailing power strategies, introduce, even in a veiled form, the power to/with analysis (Arcidiacono 2018; Cacchiarelli and Sorrentino 2018; Silva et al. 2016). Articles describing the many unfair procurement practices and strategies carried out by retailers call for state interventions aimed at reinforcing current competition laws (Daskalova 2020; Faleri 2021; Franscarelli and Ciliberti 2014; Maglaras et al. 2015; Wood et al. 2021). In many studies, an in-depth analysis of strategies led to the description of forms and sources of power using both management theories (Belaya and Hanf 2012; Collins 2007; Hingley 2005; Volpe 2011) and structural approaches based on social network theory (Kähkönen 2015; Kähkönen and Virolainen 2011; Madichie and Yamoah 2017). A group of articles in the field of business and management further extends the analysis of power relations in the distributive channel either by broadening its scope or its theoretical foundation. For example, power in vertical supply chain relations is presented as an effective means through which traceability systems can be implemented (Sanfiel-Fumero et al. 2012), and this gives firms incentives to improve food safety (Wang et al. 2019). Wang et al. (2019) demonstrated, for the pork industry in China, that as market power accumulates, pork firms may have more incentives to implement advanced risk control systems and reduce food safety violations. Other studies (Belaya and Hanf 2014; Hanf et al. 2013) use the framework of the five sources of power suggested by French and Raven (1959) for assessing food channels’ organisational arrangements.

Marketing articles refer to the study of the persuasion power of marketing strategies carried out by food manufacturers and retails (Elliott and Truman 2020, 2019; Jackson et al. 2014; Harris et al. 2020; Mulligan et al. 2021; Truman and Elliott 2019). Most of them focus on marketing strategies by promoting unhealthy food habits among children and teenagers. Although marketing articles draw attention to an important aspect of corporate power, namely the ability to influence consumer behavior, they do not address the problem of power as such and do not refer to specific theories of power. Instead, they deal with a much narrower topic that is the negative influence of advertising on the eating habits and on the health of children and teenagers. There is no political attack to corporate power and what is asked for is only an adjustment of their policies in a very specific field; accordingly, the request for public intervention is made at the level of the regulation of advertising towards minors and not at the level of competition policy. This latter observation would be useful when the price differential between obesogenic and healthy foods may offset public efforts to tackle obesity; in such a case, there is the need of antitrust interventions to tackle market power, which enables firms to receive a price premium for healthy foods (Sodano and Verneau 2013).

4.2. Political Economy: General Studies

The General Political Economy group contains nine articles, eight of which published were over the last four years, meaning that food system scholars have only recently addressed the power issue from a larger theoretical perspective. Six of them contain in their title the word political economy, and the other three contain the word power. The red thread that binds them is the acknowledgment that power and the associated political economy perspective is a central issue for the transition towards a more sustainable food system. As stated by the oldest article in this group (Dahlberg 2001), such a transition should be the fourth after the three great transitions occurred in food systems over the course of millennial human history: the transition from hunting and gathering bands to agricultural societies, the transition to city-focused societies and civilizations, and the transition to modern industrial societies. Among the forces responsible for these transitions, there have been two types of interacting structural sources of power: the built environment (made of buildings, infrastructures, technology tools, and every human made artifact) and its associated institutions (from cultural norms to rules imposed through violence and constitutional laws). Food systems stemmed from the third transition have evolved in the current global industrial food system, for which its outcome have been the following: the rupture of its ties with nature; the displacement of traditional peasant communities; the overexploitation of workers and natural resources; the emergence of new public health risks and too high environment costs. To find a way to overcome these negative outcomes, Dahlberg suggests looking at the two mentioned structural sources of power.

The theme of transition to an alternative food system frames the discourse on power and food system and allows a separation of the analysis of power over, in terms of relations of domination within the existing food system, from the analysis of power to, in terms of the possibilities (ableness) for some actors to move towards alternatives. The concept of transition implies an agreement on the existence of a mainstream concept to be refuted. At discursive/institutional level, the mainstream consists of a “broad group of economic and agricultural development thinkers, food security scholars, donor agencies, and private foundations who have shaped food system policymaking in governmental and intergovernmental spaces in adherence to a predominately ‘productionist’ perspective” (M. Anderson et al. 2019). At a physical/practical level, the mainstream consists of an industrial food production system characterized by the exercise of power over a diverse set of subjects, such as workers, peasants, smallholders, consumers, and environment.

The concept of transition entails the design of alternatives as well through higher levels of participation by non-governmental actors. Central to the alternatives discourse is, therefore, the correction of power imbalances through the empowerment (power to) of civil society (M. Anderson et al. 2019). At empirical levels, the design of alternatives has been developed based upon food sovereignty movements and the productive practices of agroecology.

In a way, the food system transition literature represents a development of the political economy literature (of which the food regime literature is an outstanding example) critical of modern capitalistic food systems that broadens the scope of the political economy perspective by also endorsing political ecology and feminist perspectives and placing the concept of power at the center of its analysis. This latter is used and developed mainly by referring to the forms of power to and power with emerging from civil society practices of resistance and change (Leach et al. 2020; McNeill 2019).

Together with the enlargement of its research scope, food system transition studies have enlarged their methods and approaches by embracing a “political economy approach focused on the dynamics of power. Such approach is deemed to be useful for analyzing and deconstructing dominant discourses and to identify and challenge power structures across food systems” (Duncan et al. 2019). The new perspectives able to enrich the food political economy analysis are as follows: the study of post-capitalist and diverse economies; feminist theories; the study of co-production of knowledge and nature; colonial studies; the demise of the anthropocentric perspective in social and environmental research.

In their intent to understand power within food systems, Baker et al. (2021a), also using the Gaventa’s power cube model, identified four levels of power shifts in food systems: a shift upwards (towards a global dimension) and downwards (towards a sub-national local dimension), away from the national loci where power relations have traditional occurred; a shift outwards, as non-state actors have come to play increasingly important role in food governance, and inwards, as markets have become increasingly concentrated through corporate strategies to gain market power within and across food supply-chain segments.

Notwithstanding the broadening of research scope and approaches in addressing power imbalances and to allow food systems to provide better outcomes, Walls et al. (2020) noticed that there is still considerable space for further work in this largely under researched area. Swinburn (2019) by answering the question “what outcomes do we want from food system?” well summarizes the goals of food system transition: human health and wellbeing, ecological health and wellbeing, social equity, and economic prosperity. However, the great transformation that would make the transition happen faces many obstacles that are mainly about governance, political economy constraints, and policy trade-offs. Four actors/loci of powers (Béné 2022) play the main roles: the resistance by transnational corporations and their shareholders; the misalignment of interests and values of governments and consumers; the fact that technological innovation (arguably the main engine of the Great Transformation) is driven by profit and not by sustainability; the failure of science to play an independent role in the critical socio-techno-environmental debate.

The General Political Economy articles clearly show that there are four fields where conflicts and power struggles in the food system occur, both inter and intra fields: 1. the economic field, populated by small- and medium-sized enterprises, large corporations and their shareholders, and consumers; 2. the formal institutional field, made by governments and public institutions, nongovernmental organisations, and international bodies; 3. the non formal institutional field, that is, the terrain of civil society with its socio-cultural milieu; 4. the science and technological system. Actors in these four fields either engage in conflicts associated with policy trade-offs or may exercise power to promote the transformative changes. With respect to the sources of power of various actors in these fields, they may be economic (wealth), institutional (public powers, laws, and regulations), informative/knowledge (human capital, expertise, and information), and socio-cultural (the cultural attitude to cooperation and civil mobilization and social capital). An example of a power struggle involving more fields, actors, and power sources is the current processes of digitization. One largely recognized risk of digitization is a further consolidation of the food system. To ensure that digitization is consistent with sustainability objectives, public intervention should address some critical issues, such as data sovereignty, increased surveillance and corporate control over farming practices, and increased influence of corporate power on a state’s regulatory choices. Corporations, through their lobbying activities, may exercise some form of agenda power in public policies’ decisional arena and, through influential social activities (often framed through the rhetoric of corporate social responsibility), may exercise some form of hegemonic power at the level of civil society, making the public more akin to bearing the costs and risks of digitization. In the end, the rise of corporate power produced by digitization could reduce transparency and democratic participation in policy decision processes.

4.3. Political Economy: Empirical Studies

Political Economy articles with empirical content introduce the issue of power in more indirect ways. They start by answering specific research questions and end up acknowledging that power issues need to be taken into account. There are four main topics addressed by these articles: the wider topic of sustainable development; the relationship between food system and health; the relationship between food security, development and food sovereignty; the topic, which overlaps with the other three topics, of alternative food systems/networks.

4.3.1. The Wider Topic of Sustainable Development

Some articles that focus on sustainability recognize that power imbalances within the food chain may hamper the effectiveness of corrective policies. For instance, corporate agribusiness dominance may shift the bioeconomy agenda towards unsustainable and unforeseen outcomes (Bastos Lima 2021); retailers may use sustainable supply chains to exert further control over their suppliers (Glover 2020); the most powerful actors across the supply chain may be able to pass risks and responsibilities for environmental impacts to weaker actors (Glover and Touboulic 2020); supermarkets, while claiming responsible behaviors, may impose private quality standards that cause fresh food waste (Devin and Richards 2018); corporate actors may use discursive power for imposing unsustainable forms of food retail governance (Fuchs and Kalfagianni 2009); climate change adaptation may exacerbate unbalanced power relations within the food chain (Nagoda and Nightingale 2017). Other articles present cases and scenarios of positive transformative changes (Bui 2021; Egal and Berry 2020; Nash et al. 2022), pointing at those forms of power to that might allow structurally weak actors, and possibly consumers, to release their agency and work to achieve positive structural changes (Friel 2021). Examples of state initiatives (Daniels and Delwiche 2022) and participatory approaches in problem-structuring processes (Herrera 2017) are presented as a means to smooth the power of actors when promoting food security resilience to climate change.

Further articles focusing on sustainability extend the analysis to the entire physical environment and natural resources (the real territory) where power relations occur. They broaden the food–water nexus and resource scarcity/food security perspectives by integrating other analytical dimensions such as time, space, and power (Kharanagh et al. 2020), also with in-depth analyses of forms of power (Jacobi and Llanque 2018; Jacobi et al. 2019). Framing the food insecurity issue in the wider socio-ecological dimension, these articles suggest that insecurities surrounding water and food are explained by political power and gender relations (Allouche 2011) and that proactively addressing power imbalances by giving voice to marginalized actors in the system (Drimie et al. 2018) is the best way to achieve food security while promoting the sustainability of global water and food systems.

4.3.2. The Relationship between Food System and Health

Articles on food, power, and health center their analysis on the economic and political power exercised by Big Food, which is the name given to the transnational corporations that drives the global consumption of unhealthy ultra-processed food and beverages (Baker et al. 2021b). Market and political practices by Big Food serve to shape consumption patterns in the processes of food system transformations in developing countries (Baker and Friel 2016) and to influence policy and decision making in the field of food safety regulation (Clapp and Scrinis 2017; Hinton 2022; Miller and Harkins 2010). Big Food also enters trade disputes to reach their goals in battles around state discrepancies in the safety and acceptability of food standards and technological innovation (Quark 2016; Schram and Townsend 2020). Moreover, in trying to legitimate their power, large corporations propose themselves as part of the solution of an unhealthy food problem by carrying out effective strategies of regulatory capture, relationship building, and marketing (Lacy-Nichols and Williams 2021).

4.3.3. The Relationship between Food Security, Development, and Food Sovereignty

Power analyses in the field of food security stem from the acknowledgement of the conflicts of interests among the parties affected by food security policies. They call for the need to align local governments’ choices with the involved parties (Slade and Carter 2016; Sneyd et al. 2015) and to empower citizens to build a community food security agenda that is able to include issues at odds with stakeholders in positions of power (McCullum et al. 2003). They show that the same food aid may indirectly enhance food security by reinforcing inequalities and local power structures (Nagoda 2017). Power analyses allow highlighting the limits of the “multistakeholder” approach to policy deliberation, which proves to be ineffective when power imbalances are negated (McKeon 2017), and to frame instead the food security issue in a broader political perspective. This latter clearly frames the issue of food security as the conflict between the industrial food system (the Big Food of health-related literature) and territory-embedded systems at the center human rights, including family farming and peasant agroecology (McKeon 2021). Such a conflict may be addressed by the food sovereignty research praxis (Levkoe et al. 2019), which is made of three pillars: people (humanizing research relationships), power (equalizing power relations), and change (pursuing transformative orientations).

4.3.4. Alternative Food Systems/Networks

The topic of alternative food systems includes either the representation of new paradigms such as agroecology, which is able to transform the current agri-food system and to achieve sustainability and a more equitable distribution of power and resources (C. R. Anderson et al. 2019; Gliessman et al. 2019; Hvitsand 2016; Lappé 2016; Sanderson Bellamy and Ioris 2017), or the study of alternative food networks at a local level. These latter paradigms refer to organic- (Nuutila and Kurppa 2017) and urban-agriculture-based food supply chains (Campbell 2016; McIvor and Hale 2015) and local food systems supporting rural communities and sustainable food chains (Buchan et al. 2019; Nakandala et al. 2020; Poças Ribeiro et al. 2021; Trivette 2017). Here, the addressed power issues are those related to the fight against Big Food, the balance of power among large retailers and small-scale alternative farms within the distributive channel, and governance struggles and the role of different actors in supporting alternative food networks.

4.4. Other Articles

The heterogenous group of articles in our selection specifically address the following topics that are underrepresented in the overall power and food literature: the role of power in shaping technological innovation within the system, when the assumptions of neutrality and determinism of science and technology are released (Bruce 2002; Elg and Johansson 1997; Kimura and Kinchy 2020; Sodano 2018); the role of food used as a source of power in international relations, either as the soft power of culinary diplomacy (Farina 2018; Hongzhou 2020; Teughels 2021) or as the quite hard power of sanctions (Seifullaeva et al. 2017); the role of the power of the financial sector vis-à-vis the other actors in the food chain (Fuchs et al. 2013; Greenberg 2017); the unpredictable outcomes of practices and behaviors, such as sustainable consumption (Fuchs and Boll 2018) or philanthrocapitalism (Thompson 2018), when power is taken into account.

5. Conclusions

The recent growth in the number of publications that mention the word power shows that there is a high and growing interest in the study of the dimension of power in relation to the agri-food sector. The presence of some wide-ranging reviews shows that the study of power is now a fairly consolidated field of study.

The analyzed literature allows adding many structural, institutional, and socio-cultural components to the description of the agri-food system that enormously enrich the knowledge of the actors who populate the agri-food system with respect to their strategies and the associated effects on the development and change dynamics of the system. The subjects most frequently called into question are large corporations, which are protagonists of both consolidation processes and of the production and management choices responsible for environmental and health problems; public regulators, called to stem corporate power (either through competition policy, or through command and control instruments, or through governance mechanisms with private partnership) and to push the system towards outcomes in line with the general interests of society; and civil society, made up of individuals and non-profit associations, which act as spokespersons for the general interest and induce the other two subjects to align with them. The sustainability theme is frequently declined in terms of a change in paradigm and search for alternatives to the industrial paradigm of Big Food. With respect to these topics, two major power analysis issues emerge: corporate power and the resistance of civil society and rural communities through empowerment and mechanisms of participatory democracy.

However, our literature review also shows that the study of power in the food system is still in its infancy, as made clear by the following limitations that emerge from the analyzed articles.

The first limitation concerns the scant use of analytical frameworks and definitions offered by the theory of power, which were mentioned only by a few articles. In relation to the economic strand, what is missing is the use of a theory of contracts for the analysis of vertical relationships. Such a theory would allow an improved identification of the sources of power, distinguishing between those related to information asymmetry from those related to the legal context and the level of enforcement or from those related to the position in the social network structure. Little use is also made of institutionalist theories of the firm, which would allow improved analyses of the social and political dimension of corporate power. With respect to the political economy strand, it is characterized by an eclectic attitude to the analysis of power. While agenda and discursive power are generally well characterized, the distinction between power over and power to is poorly stressed, with blurred distinctions between relational contexts of domination, paternalism, or influence. Many studies start from a systemic conception of power, which on one hand helps to view the complexity of interrelationships between various components of the agri-food system, but, on the other hand, somehow reduces the analytical and normative value of the concept of power. Some articles, in an attempt to face the unsolved dilemma of the relationship between strategy and structure (Archer 1995), endorse postmodernist conceptions of power, such as a Foucauldian one, that amplify the productive meaning of power and its ubiquitous dimension.

A second limitation is the lack of attention paid to some relevant issues. An example is the analysis of power as a driving force of technological innovation, which is of uttermost importance when recognizing that innovation is not a product of some “natural” evolution of the system (as supported by the idea of technological determinism) but is rather the effect of the conscious and strategic choices of powerful actors. A second example is given by the conflicts between states in relation to the strategic use of the agri-food sector for purposes of national security and/or geopolitical strategies, especially when the same military power can be strengthened by the strategic control of food resources. A third example is the role of the financial sector in power relations within the system, which is due both to the fact that the companies in the financial sector are often owners of industrial and agricultural companies (through corporate control by investment funds and hedge funds) and to the fact that the process of financialization of industrial and agricultural sectors has entailed a power shift from stakeholders to shareholders.

Finally, the third limitation of the examined literature is the scant attention paid to the study of the sources of power. In particular, there are scant in-depth investigations of the ownership structure of companies in the agri-food sector and, therefore, of their ableness of mobilizing economic resources, which is one of the main sources of power. There is also a limited description of the typology of procurement contracts in vertical relations, which can strongly affect power relations. Investments in propaganda communication and lobbying activities by large companies are also poorly investigated.

A general conclusion of our review is that there is a growing interest in the study of power within the food system and that there are many analytical tools that are still underused and that could help address the issue of sustainable policy design. Analyzing power within the food system may facilitate the creation of a road map for sustainability. In the first place, starting from the perspective of power means recognizing that the definition of policy objectives entails value judgments, the endorsement of which is made through the exercise of power; this latter concept needs to be analyzed by evaluating different forms of the legitimization of policy makers’ power. Once objectives are defined, the analysis of power makes it possible, when choosing intervention tools, to take into account the power relations between the subjects involved; this in order to reduce the imbalance of power between various actors and to align their interests with those of the entire society. Power relations should be described by not only identifying the subjects but also the sources of power, considering both actors’ own endowments and all power sources deriving from the institutional context.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.S. and M.T.G.; methodology, V.S. and M.T.G.; writing—original draft preparation, V.S. and M.T.G.; writing—review and editing, V.S. and M.T.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study did not require ethical approval.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aalto-Setälä, Ville. 2002. The effect of concentration and market power on food prices: Evidence from Finland. Journal of Retailing 78: 207–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Amy. 2018. The Power of Feminist Theory: Domination, Resistance, Solidarity. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Allouche, Jeremy. 2011. The sustainability and resilience of global water and food systems: Political analysis of the interplay between security, resource scarcity, political systems and global trade. Food Policy 36: S3–S8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Colin Ray, Janneke Bruil, Michael Jahi Chappell, Csilla Kiss, and Michel Patrick Pimbert. 2019. From transition to domains of transformation: Getting to sustainable and just food systems through agroecology. Sustainability 11: 5272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Molly, Nicholas Nisbett, Chantal Clément, and Jody Harris. 2019. Introduction: Valuing Different Perspectives on Power in the Food System. IDS Bulletin 50: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, Margaret S. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, Davide. 2018. Promises and failures of the cooperative food retail system in Italy. Social Sciences 7: 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assefa, Tsion Taye, Miranda P. M. Meuwissen, Cornelis Gardebroek, and Alfons G. J. M. Oude Lansink. 2017. Price and volatility transmission and market power in the German fresh pork supply chain. Journal of Agricultural Economics 68: 861–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelino, Flor. 2017. Power in sustainability transitions: Analysing power and (dis) empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environmental Policy and Governance 27: 505–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachrach, Peter, and Morton S. Baratz. 1962. Two faces of power. American Political Science Review 56: 947–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Phillip, and Sharon Friel. 2016. Food systems transformations, ultra-processed food markets and the nutrition transition in Asia. Globalization and Health 12: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Phillip, Jennifer Lacy-Nichols, Owain Williams, and Ronald Labonté. 2021a. The political economy of healthy and sustainable food systems: An introduction to a special issue. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 734–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Phillip, Katheryn Russ, Manho Kang, Thiago M. Santos, Paulo A. R. Neves, Julie Smith, Gillian Kingston, Melissa Mialon, Mark Lawrence, and Benjamin Wood. 2021b. Globalization, first-foods systems transformations and corporate power: A synthesis of literature and data on the market and political practices of the transnational baby food industry. Globalization and Health 17: 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barros, Pedro Pita, Duarte Brito, and Diogo de Lucena. 2006. Mergers in the food retailing sector: An empirical investigation. European Economic Review 50: 447–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastos Lima, Mairon G. 2021. Corporate power in the bioeconomy transition: The policies and politics of conservative ecological modernization in Brazil. Sustainability 13: 6952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaya, Vera, and Jon Henrich Hanf. 2012. Managing Russian agri-food supply chain networks with power. Journal on Chain and Network Science 12: 215–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaya, Vera, and Jon Henrich Hanf. 2014. Power and influence in Russian agri-food supply chains: Results of a survey of local subsidiaries of multinational enterprises. Journal for East European Management Studies 19: 160–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Béné, Christophe. 2022. Why the Great Food Transformation may not happen–A deep-dive into our food systems’ political economy, controversies and politics of evidence. World Development 154: 105881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, Sanjib, and Rigoberto A. Lopez. 1997. Oligopoly power in the food and tobacco industries. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 79: 1035–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonanno, Alessandro, and Rigoberto A. Lopez. 2009. Competition effects of supermarket services. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 91: 555–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, Céline, and Zohra Bouamra-Mechemache. 2016. Organic label, bargaining power, and profit-sharing in the French fluid milk market. American Journal of Agricultural Economics 98: 113–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonnet, Céline, Zohra Bouamra-Mechemache, and Gordon Klein. 2022. National brands in hard discounters: Market expansion and bargaining power effects. European Review of Agricultural Economics 47: 819–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowles, Samuel, and Herbert Gintis. 1998. Power in Competitive Exchange. In The Politics and Economics of Power. Edited by Samuel Bowles, Maurizio Franzini and Ugo Pagano. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce, Donald M. 2002. A social contract for biotechnology: Shared visions for risky technologies? Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics 15: 279–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchan, Robert, Denise S. Cloutier, and Avi Friedman. 2019. Transformative incrementalism: Planning for transformative change in local food systems. Progress in Planning 134: 100424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bui, Sibylle. 2021. Enacting Transitions—The Combined Effect of Multiple Niches in Whole System Reconfiguration. Sustainability 13: 6135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacchiarelli, Luca, and Alessandro Sorrentino. 2018. Market power in food supply chain: Evidence from Italian pasta chain. British Food Journal 120: 2129–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, Lindsay K. 2016. Getting farming on the agenda: Planning, policymaking, and governance practices of urban agriculture in New York City. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 19: 295–305. [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin, Edward Hastings. 1933. Theory of Monopolistic Competition: A Re-Orientation of the Theory of Value, 1st ed. London: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Clapp, Jennifer, and Doris Fuchs. 2009. Agrifood corporations, global governance, and sustainability: A framework for analysi. Corporate Power in Global Agrifood Governance, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clapp, Jennifer, and Gyorgy Scrinis. 2017. Big food, nutritionism, and corporate power. Globalizations 14: 578–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coase, Ronald Harry. 1937. The nature of the firm. Economica 4: 386–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, Alan M. 2007. Retail control of manufacturers’ product-related activities: Evidence from the Irish food manufacturing sector. Journal of Food Products Marketing 13: 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connor, John M., Richard T. Rogers, and Vijay Bhagavan. 1996. Concentration change and countervailing power in the US food manufacturing industries. In Economics of Innovation: The Case of Food Industry. Contributions to Economics. Edited by Giovanni Galizzi and Luciano Venturini. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media, pp. 73–99. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Karen S., and Richard M. Emerson. 1978. Power, Equity and Commitment in Exchange Networks. American Sociological Review 43: 721–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crozier, Michel, and Erhard Friedberg. 1977. L’acteur et le système. Paris: Editions du Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl, Robert A. 1957. The concept of power. Behavioral Science 2: 201–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahl, Robert. 1986. Power as the Control of Behaviour. In Power. Edited by Steven Lukes. New York: New York University Press, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg, Kenneth A. 2001. Democratizing society and food systems: Or how do we transform modern structures of power? Agriculture and Human Values 18: 135–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Jiawu, Xun Li, and Hailong Cai. 2018. Market power, scale economy and productivity: The case of China’s food and tobacco industry. China Agricultural Economic Review 10: 313–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniels, Paula, and Alexa Delwiche. 2022. Future Policy Award 2018: The Good Food Purchasing Program, USA. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 5: 576776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daskalova, Victoria. 2020. Regulating unfair trading practices in the EU agri-food supply chain: A case of counterproductive regulation? Yearbook of Antitrust and Regulatory Studies 13: 7–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devin, Bree, and Carol Richards. 2018. Food waste, power, and corporate social responsibility in the Australian food supply chain. Journal of Business Ethics 150: 199–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dowding, Keith M. 1996. Power. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drimie, Scott, Ralph Hamann, Annie P. Manderson, and Norah Mlondobozi. 2018. Creating transformative spaces for dialogue and action. Ecology and Society 23: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, Jessica, Charles Z. Levkoe, and Ana Moragues-Faus. 2019. Envisioning new horizons for the political economy of sustainable food systems. Bulletin 50: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egal, Florence, and Elliot M. Berry. 2020. Moving towards sustainability—Bringing the threads together. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems 4: 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elg, Ulf, and Ulf Johansson. 1997. Decision making in inter-firm networks as a political process. Organization Studies 18: 361–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, Charlene, and Emily Truman. 2019. Measuring the power of food marketing to children: A review of recent literature. Current Nutrition Reports 8: 323–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elliott, Charlene, and Emily Truman. 2020. The power of packaging: A scoping review and assessment of child-targeted food packaging. Nutrients 12: 958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faleri, Claudia. 2021. Non basta la repressione. A proposito di caporalato e sfruttamento del lavoro in agricoltura’ Lavoro e Diritto 35: 257–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fałkowski, Jan, Agata Malak-Rawlikowska, and Dominika Milczarek-Andrzejewska. 2017. Farmers’ self-reported bargaining power and price heterogeneity: Evidence from the dairy supply chain. British Food Journal 119: 1672–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, Felice. 2018. Japan’s gastrodiplomacy as soft power: Global washoku and national food security. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia 17: 152–67. [Google Scholar]

- Franscarelli, Angelo, and Stefano Ciliberti. 2014. Mandatory Rules in Contracts of Sale of Food and Agricultural Products in Italy: An Assessment of Article 62 of Law 27/2012’. Paper presented at the 140th Seminar European Association of Agricultural Economists, Perugia, Italy, December 13–15. [Google Scholar]

- French, John, and Bertram H. Raven. 1959. The Bases of Social Power. In Studies in Social Power. Edited by Dorwin Cartwright. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, pp. 150–67. [Google Scholar]

- Friedmann, Harriet. 1987. International regimes of food and agriculture since 1870. Peasants and Peasant Societies 2: 247–58. [Google Scholar]

- Friel, Sharon. 2021. Redressing the corporate cultivation of consumption: Releasing the weapons of the structurally weak. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 784–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Doris, and Frederike Boll. 2018. Sustainable consumption. In Global Environmental Politics. London: Routledge, pp. 83–102. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs, Doris, and Agni Kalfagianni. 2009. Discursive power as a source of legitimation in food retail governance. The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 19: 553–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Doris, Richard Meyer-Eppler, and Ulrich Hamenstädt. 2013. Food for thought: The politics of financialization in the agrifood system. Competition Change 17: 219–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaventa, John. 1982. Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley. Champaign: University of Illinois Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gliessman, Steve, Harriet Friedmann, and Philip H. Howard. 2019. Agroecology and food sovereignty. Bulletin 50: 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, Jane. 2020. The dark side of sustainable dairy supply chains. International Journal of Operations Production Management 40: 1801–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glover, Jane, and Anne Touboulic. 2020. Tales from the countryside: Unpacking “passing the environmental buck” as hypocritical practice in the food supply chain. Journal of Business Research 121: 33–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenberg, Stephen. 2017. Corporate power in the agro-food system and the consumer food environment in South Africa. The Journal of Peasant Studies 44: 467–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, Sanford J., and Oliver D. Hart. 1986. The Costs and Benefits of Ownership: A Theory of Vertical and Lateral Integration. Journal of Political Economy 94: 691–719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanf, Jon H., Vera Belaya, and Erik Schweickert. 2013. Who’s Got the Power? An Evaluation of Power Distribution in the German Agribusiness Industry. The Ethics and Economics of Agrifood Competition 20: 211–16. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, Jennifer L., Victoria Webb, Shane J. Sacco, and Jennifer L. Pomeranz. 2020. Marketing to children in supermarkets: An opportunity for public policy to improve children’s diets. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17: 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, Oliver, and Moore John. 1990. Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy 98: 1119–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugaard, Mark. 1997. The Constitution of Power: A Theoretical Analysis of Power, Knowledge and Structure. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haugaard, Mark, ed. 2002. Power: A Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- He, Xi. 2021. Political and economic determinants of export restrictions in the agricultural and food sector. Agricultural Economics 53: 439–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera, Hugo. 2017. Resilience for whom? The problem structuring process of the resilience analysis. Sustainability 9: 1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingley, Martin. K. 2005. Power imbalanced relationships: Cases from UK fresh food supply. International Journal of Retail Distribution Management 33: 551–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinton, Lucy. 2022. Discursive Power: Trade Over Health in CARICOM Food Labelling Policy. Frontiers in Communication 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirsch, Stefan, and Maximilian Koppenberg. 2020. Power imbalances in French food retailing: Evidence from a production function approach to estimate market power. Economics Letters 194: 109387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongzhou, Zhang. 2020. The US-China Trade War: Is Food China’s Most Powerful Weapon? Asia Policy 27: 59–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hvitsand, Christine. 2016. Community supported agriculture (CSA) as a transformational act—Distinct values and multiple motivations among farmers and consumers. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems 40: 333–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, Michaela, Paul Harrison, Boyd Swinburn, and Mark Lawrence. 2014. Unhealthy food, integrated marketing communication and power: A critical analysis. Critical Public Health 24: 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, Johanna, and Aymara Llanque. 2018. When We Stand up, They Have to Negotiate with Us: Power Relations in and between an Agroindustrial and an Indigenous Food System in Bolivia. Sustainability 10: 4001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobi, Johanna, Grace Wambugu, Mariah Ngutu, Horacio Augstburger, Veronica Mwangi, Aymara Llanque Zonta, Stephen Otieno, Boniface P. Kiteme, José M. F. Delgado Burgoa, and Stephan Rist. 2019. Mapping food systems: A participatory research tool tested in Kenya and Bolivia. Mountain Research and Development 39: R1–R11. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, Jørgen Dejgaard. 2009. Market power behaviour in the Danish food marketing chain. Journal on Chain and Network Science 9: 43–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnstone, Phil, and Peter Newell. 2018. Sustainability transitions and the state. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 27: 72–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, Anni-Kaisa. 2015. The context-dependency of buyer-supplier power. International Journal of Procurement Management 8: 396–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, Anni-Kaisa, and Veli Matti Virolainen. 2011. Sources of structural power in the context of value nets. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management 17: 109–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharanagh, Samaneh Ghafoori, Mohammad Ebrahim Banihabib, and Saman Javadi. 2020. An MCDM-based social network analysis of water governance to determine actors’ power in water-food-energy nexus. Journal of Hydrology 581: 124382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, Aya H., and Abby Kinchy. 2020. Citizen science in North American agri-food systems: Lessons learned. Citizen Science: Theory and Practice 5: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kufel-Gajda, Justyna. 2017. Monopolistic markups in the Polish food sector. Equilibrium. Quarterly Journal of Economics and Economic Policy 12: 147–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacy-Nichols, Jennifer, and Owain Williams. 2021. Part of the Solution: Food Corporation Strategies for Regulatory Capture and Legitimacy. International Journal of Health Policy and Management 10: 845–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lappé, Frances Moor. 2016. Farming for a small planet: Agroecology now. Development 59: 299–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leach, Melissa, Nicholas Nisbett, Lídia Cabral, Jody Harris, Naomi Hossain, and John Thompson. 2020. Food politics and development. World Development 134: 105024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levkoe, Charles Z., Josh Brem-Wilson, and Colin R. Anderson. 2019. People, power, change: Three pillars of a food sovereignty research praxis. The Journal of Peasant Studies 46: 1389–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Tim. 2017. Forty years of price transmission research in the food industry: Insights, challenges and prospects. Journal of Agricultural Economics 68: 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, Tim A., Steve McCorriston, C. Wyn Morgan, and Habtu T. Weldegebriel. 2009. Buyer power in UK food retailing: A ‘first-pass’ test. Journal of Agricultural Food Industrial Organization 7: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Rigoberto A., Azzeddine M. Azzam, and Carmen Lirón-España. 2002. Market power and/or efficiency: A structural approach. Review of Industrial Organization 20: 115–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, Rigoberto A., Xi He, and Azzeddine Azzam. 2018. Stochastic frontier estimation of market power in the food industries. Journal of Agricultural Economics 69: 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loy, Jens-Peter, Christoph R. Weiss, and Thomas Glauben. 2016. Asymmetric cost pass-through? Empirical evidence on the role of market power, search and menu costs. Journal of Economic Behavior Organization 123: 184–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lukes, Steven. 1974. Power: A Radical View, 1st ed. New York: Macmillan International Higher Education. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Lukes, Steven. 2005. Power: A Radical View, 2nd ed. New York: Palgrave Macmillan Houndmills. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Meilin, Tina L. Saitone, Richard J. Volpe, Richard J. Sexton, and Michelle Saksena. 2019. Market concentration, market shares, and retail food prices: Evidence from the US Women, Infants, and Children Program. Applied Economic Perspectives and Policy 41: 542–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madichie, Nnamdi O., and Fred A. Yamoah. 2017. Revisiting the European horsemeat scandal: The role of power asymmetry in the food supply chain crisis. Thunderbird International Business Review 59: 663–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglaras, George, Michael Bourlakis, and Christos Fotopoulos. 2015. Power-imbalanced relationships in the dyadic food chain: An empirical investigation of retailers’ commercial practices with suppliers. Industrial Marketing Management 48: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marfels, Christian. 1992. Concentration and buying power: The ease of German food distribution. International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 2: 233–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCullum, Christine, David Pelletier, Donald Barr, and Jennifer Wilkins. 2003. Agenda setting within a community-based food security planning process: The influence of power. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior 35: 189–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McIvor, David W., and James Hale. 2015. Urban agriculture and the prospects for deep democracy. Agriculture and Human Values 32: 727–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, Nora. 2017. Are equity and sustainability a likely outcome when foxes and chickens share the same coop? Critiquing the concept of multistakeholder governance of food security. Globalizations 14: 379–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKeon, Nora. 2021. Let’s Reclaim Our Food Sovereignty and Reject the Industrial Food System! Development 64: 292–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeill, Desmond. 2019. Reflections on IPES-food: Can power analysis change the world? IDS Bulletin 50: 27–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, David, and Claire Harkins. 2010. Corporate strategy, corporate capture: Food and alcohol industry lobbying and public health. Critical Social Policy 30: 564–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morriss, Peter. 2002. Power: A Philosophical Analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan, Christine, Monique Potvin Kent, Laura Vergeer, Anthea K. Christoforou, and Mary R. LAbbé ’. 2021. Quantifying child-appeal: The development and mixed-methods validation of a methodology for evaluating child-appealing marketing on product packaging. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18: 4769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagoda, Sigrid. 2017. Rethinking Food Aid in a Chronically Food-Insecure Region: Effects of Food Aid on Local Power Relations and Vulnerability Patterns in Northwestern Nepal. IDS Bulletin 48: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Nagoda, Sigrid, and Andrea J. Nightingale. 2017. Participation and power in climate change adaptation policies: Vulnerability in food security programs in Nepal. World Development 100: 85–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakandala, Dilupa, Meg Smith, and Henry Lau. 2020. Shared power and fairness in trust-based supply chain relationships in an urban local food system’. British Food Journal 122: 870–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nash, Kirsty L., Ingrid Van Putten, Karen A. Alexander, Silvana Bettiol, Christopher Cvitanovic, Anna K. Farmery, Emily J. Flies, Sierra Ison, Rachel Kelly, and Mary Mackay. 2022. Oceans and society: Feedbacks between ocean and human health. Reviews in Fish Biology and Fisheries 32: 161–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nussbaum, Martha, and Amartya Sen. 1993. The Quality of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Nuutila, Jaakko, and Sirpa Kurppa. 2017. Two main challenges that prevent the development of an organic food chain at local and national level—An exploratory study in Finland. Organic Agriculture 7: 379–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, Matthew J., Joanne E. McKenzie, Patrick M. Bossuyt, Isabelle Boutron, Tammy C. Hoffmann, Cynthia D. Mulrow, Larissa Shamseer, Jennifer M. Tetzlaff, Elie A. Akl, Sue E. Brennan, and et al. 2021. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. PLoS Medicine 18: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pansardi, Pamela. 2012. Power to and power over: Two distinct concepts of power? Journal of Political Power 5: 73–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poças Ribeiro, Ana, Robert Harmsen, Giuseppe Feola, Jesús Rosales Carréon, and Ernst Worrell. 2021. Organising alternative food networks (AFNs): Challenges and facilitating conditions of different AFN types in three EU countries. Sociologia Ruralis 61: 491–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pranckutė, Raminta. 2021. Web of Science (WoS) and Scopus: The titans of bibliographic information in today’s academic world. Publications 9: 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quark, Amy. 2016. Ratcheting up protective regulations in the shadow of the WTO: NGO strategy and food safety standard-setting in India. Review of International Political Economy 23: 872–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, Raghuram G., and Luigi Zingales. 1998. Power in a Theory of the Firm. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113: 387–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezitis, Anthony, and Maria Kalantzi. 2012. Measuring market power and welfare losses in the Greek food and beverages manufacturing industry. Journal of Agricultural Food Industrial Organization 10: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, Joan. 1933. The Economics of Imperfect Competition. London: McMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Rollings, Neil. 2021. The vast and unsolved enigma of power: Business history and business power. Enterprise & Society 22: 893–920. [Google Scholar]