Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples?

Abstract

1. Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples?

2. Literature Review

2.1. Marriages and Linked Lives across the Life Course

2.2. Disability, Divorce, and Marital Quality among Older Couples

2.3. Basic Care Disability, Caregiving, and Marital Dynamics among Older Different-Sex Couples

2.4. Summary of Hypotheses

3. Methods

3.1. Data

3.2. Measures

3.3. Analytic Strategy

4. Results

4.1. Marital Status by Wave

4.2. Sample Characteristics of Analytic Sample

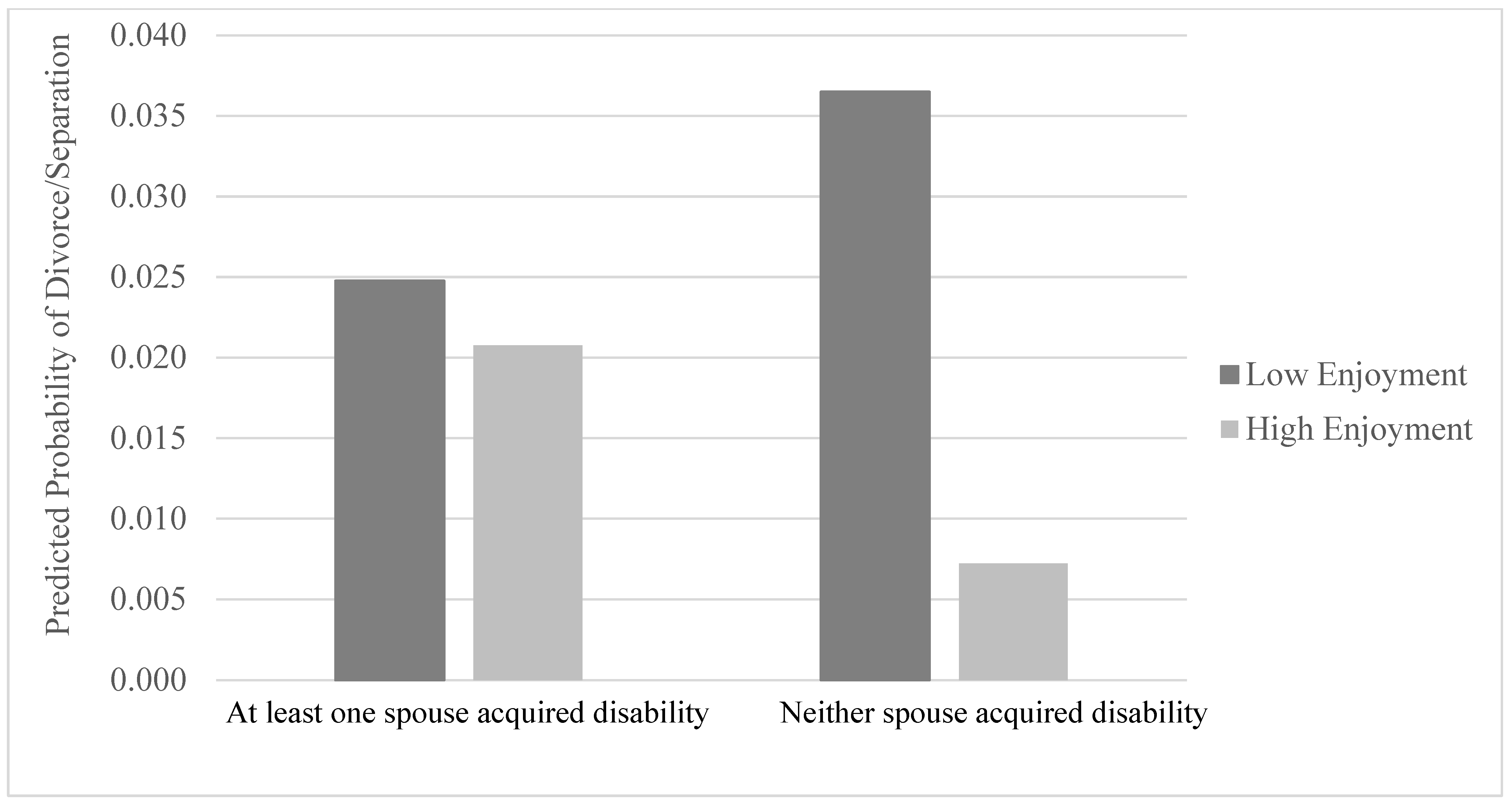

4.3. Risk of Divorce/Separation among Late Midlife Couples

4.4. Sensitivity Analyses

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- AARP and National Alliance for Caregiving. 2020. Caregiving in the United States 2020. Washington, DC: AARP. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, Susan M., Frances Goldscheider, and Desirée A. Ciambrone. 1999. Gender Roles, Marital Intimacy, and Nomination of Spouse as Primary Caregiver. The Gerontologist 39: 150–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, Paul D. 1982. Discrete-time Methods for the Analysis of Event Histories. Sociological Methodology 13: 61–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allison, Paul D. 2014. Event History and Survival Analysis: Regression for Longitudinal Event Data. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Amato, Paul R., and Bryndl Hohmann-Marriott. 2007. A Comparison of High-And Low-Distress Marriages That End In Divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 621–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, Jessie. 1972. The Future of Marriage. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blekesaune, Morten, and Anne E. Barrett. 2005. Marital Dissolution and Work Disability: A Longitudinal Study of Administrative Data. European Sociological Review 21: 259–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerner, Kathrin, Daniela S. Jopp, Deborah Carr, Laura Sosinsky, and Se-Kang Kim. 2014. “His” and “Her” Marriage? The Role of Positive and Negative Marital Characteristics in Global Marital Satisfaction among Older Adults. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Social Sciences 69: 579–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Bookwala, Jamila. 2012. Marriage and Other Partnered Relationships in Middle and Late Adulthood. In Handbook of Families and Aging. Edited by Rosemary Blieszner and Victoria H. Bedford. Westport: Praeger/ABC-CLIO, pp. 91–123. [Google Scholar]

- Brinig, Margaret F., and Douglas W. Allen. 2000. ‘These Boots Are Made For Walking’: Why Most Divorce Filers Are Women. American Law and Economics Review 2: 126–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Susan L., and I-Fen Lin. 2012. The Gray Divorce Revolution: Rising Divorce Among Middle-Aged And Older Adults, 1990–2010. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 67: 731–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Tyson H., and David F. Warner. 2008. Divergent Pathways? Racial/Ethnic Differences in Older Women’s Labor Force Withdrawal. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Social Sciences 63: S122–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Susan L., and Matthew R. Wright. 2017. Marriage, Cohabitation, and Divorce in Later Life. Innovation in Aging 1: igx015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Susan L., I-Fen Lin, Anna M. Hammersmith, and Matthew R. Wright. 2019. Repartnering Following Gray Divorce: The Roles of Resources and Constraints for Women and Men. Demography 56: 503–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, Susan L., I-Fen Lin, and Kagan A. Mellencamp. 2021. Does the Transition to Grandparenthood Deter Gray Divorce? A Test of the Braking Hypothesis. Social Forces 99: 1209–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bulanda, Jennifer Roebuck. 2011. Gender, Marital Power, and Marital Quality in Later Life. Journal of Women & Aging 23: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulanda, Jennifer Roebuck, J. Scott Brown, and Takashi Yamashita. 2016. Marital Quality, Marital Dissolution, and Mortality Risk during the Later Life Course. Social Science & Medicine 165: 119–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, Deborah, Vicki A. Freedman, Jennifer C. Cornman, and Norbert Schwarz. 2014. Happy Marriage, Happy Life? Marital Quality and Subjective Well-Being in Later Life. Journal of Marriage and Family 76: 930–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, Kerwin Kofi, and Melvin Stephens, Jr. 2004. Job Displacement, Disability, and Divorce. Journal of Labor Economics. 22, pp. 489–522. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/381258 (accessed on 17 December 2021).

- Connolly, Deirdre, Jess Garvey, and Gabrielle McKee. 2017. Factors Associated with ADL/IADL Disability In Community Dwelling Older Adults In The Irish Longitudinal Study On Ageing (TILDA). Disability and Rehabilitation 39: 809–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crowley, Jocelyn Elise. 2019. Gray Divorce: Explaining Midlife Marital Splits. Journal of Women & Aging 31: 49–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elder, Glen H., Monica Kirkpatrick Johnson, and Robert Crosnoe. 2003. The Emergence and Development of Life Course Theory. In Handbook of the Life Course. Edited by Jeylan T. Mortimer and Michael J. Shanahan. Boston: Springer, pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- England, Paula, and Elizabeth Aura McClintock. 2009. The Gendered Double Standard of Aging in US Marriage Markets. Population and Development Review 35: 797–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flood, Sarah M., Katie R. Genadek, and Phyllis Moen. 2018. Does Marital Quality Predict Togetherness? Couples’ Shared Time and Happiness during Encore Adulthood. Minnesota Population Center Working Paper Series, 1–39. [Google Scholar]

- Genadek, Katie R., Sarah M. Flood, and Phyllis Moen. 2019. For Better or Worse? Couples’ Time Together In Encore Adulthood. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 74: 329–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glantz, Michael J., Marc C. Chamberlain, Qin Liu, Chung-Cheng Hsieh, Keith R. Edwards, Alixis Van Horn, and Lawrence Recht. 2009. Gender Disparity in the Rate of Partner Abandonment in Patients with Serious Medical Illness. Cancer 115: 5237–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Health and Retirement Study (HRS). 2021. (RAND HRS Longitudinal File 2018) Public Use Dataset. Produced and Distributed by the University of Michigan with Funding from the National Institute on Aging (Grant Number NIA U01AG009740). Ann Arbor: Health and Retirement Study. [Google Scholar]

- Joung, Inez M. A., H. Dike Van De Mheen, Karien Stronks, Frans W. A. Van Poppel, and Johan P. Mackenbach. 1998. A Longitudinal Study of Health Selection in Marital Transitions. Social Science & Medicine 46: 425–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalmijn, Matthijs, and Anne-Rigt Poortman. 2006. His or Her Divorce? The Gendered Nature of Divorce and Its Determinants. European Sociological Review 22: 201–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karraker, Amelia, and Kenzie Latham. 2015. In Sickness and In Health? Physical Illness as a Risk Factor for Marital Dissolution in Later Life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 56: 420–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keating, Norah, Jacquie Eales, Laura Funk, Janet Fast, and Joohong Min. 2019. Life Course Trajectories of Family Care. International Journal of Care and Caring 3: 147–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirchhoff, Anne C., Jaehee Yi, Jennifer Wright, Echo L. Warner, and Ken R. Smith. 2012. Marriage and Divorce among Young Adult Cancer Survivors. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 6: 441–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, I-Fen, Susan L. Brown, Matthew R. Wright, and Anna M. Hammersmith. 2018. Antecedents of Gray Divorce: A Life Course Perspective. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 73: 1022–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Noël-Miller, Claire M. 2011. Partner Caregiving in Older Cohabiting Couples. Journals of Gerontology Series B: Social Sciences 66: 341–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Penning, Margaret J., and Zheng Wu. 2019. Caregiving and Union Instability in Middle and Later Life. Journal of Marriage and Family 81: 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Picavet, H. S. J., and N. Hoeymans. 2002. Physical Disability in the Netherlands: Prevalence, Risk Groups and Time Trends. Public Health 116: 231–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racher, Frances E. 2002. Synergism of Frail Rural Elderly Couples: Influencing Interdependent Independence. Journal of Gerontological Nursing 28: 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rogers, Stacy J., and Paul R. Amato. 2000. Have Changes In Gender Relations Affected Marital Quality? Social Forces 79: 731–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settersten, Richard A., Jr. 2015. Relationships in Time and the Life Course: The Significance of Linked Lives. Research in Human Development 12: 217–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singleton, Perry. 2012. Insult to Injury Disability, Earnings, and Divorce. Journal of Human Resources 47: 972–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teachman, Jay. 2010. Work-Related Health Limitations, Education, and the Risk of Marital Disruption. Journal of Marriage and Family 72: 919–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomeer, Mieke Beth, and Kirsten Ostergren Clark. 2021. The Development of Gendered Health-Related Support Dynamics over the Course of a Marriage. Journal of Women & Aging 33: 153–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umberson, Debra, Kristi Williams, Daniel A. Powers, Meichu D. Chen, and Anna M. Campbell. 2005. As Good As It Gets? A Life Course Perspective on Marital Quality. Social Forces 84: 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Umberson, Debra, Mieke Beth Thomeer, Corinne Reczek, and Rachel Donnelly. 2016. Physical Illness in Gay, Lesbian, and Heterosexual Marriages: Gendered Dyadic Experiences. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 57: 517–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Gasse, Dries, and Dimitri Mortelmans. 2020. Social Support In The Process Of Household Reorganization after Divorce. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 37: 1927–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbrugge, Lois M., and Alan M. Jette. 1994. The Disablement Process. Social Science & Medicine 38: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waite, Linda J., and Lee A. Lillard. 1991. Children and Marital Disruption. American Journal of Sociology 96: 930–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Lynn K., Alan Booth, and John N. Edwards. 1986. Children and Marital Happiness: Why The Negative Correlation? Journal of Family Issues 7: 131–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Sven E., and Shawn L. Waddoups. 2002. Good Marriages Gone Bad: Health Mismatches as a Cause of Later-Life Marital Dissolution. Population Research and Policy Review 21: 505–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yorgason, Jeremy B., Alan Booth, and David Johnson. 2008. Health, Disability, and Marital Quality: Is the Association Different for Younger versus Older Cohorts? Research on Aging 30: 623–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Waves | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | Total % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Married | 3965 | 3559 | 3205 | 2869 | 2619 | 2363 | 2171 | 1977 | 1780 | 1555 | 1360 | 1136 | 924 | 719 | 18.1 |

| Divorced/Separated | 56 | 42 | 32 | 13 | 17 | 11 | 11 | 3 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 5.3 | |

| Widowed | 84 | 108 | 124 | 122 | 131 | 112 | 120 | 142 | 168 | 145 | 175 | 156 | 138 | 43.5 | |

| Attrited | 270 | 204 | 180 | 115 | 108 | 69 | 63 | 52 | 46 | 45 | 47 | 48 | 67 | 33.1 |

| Mean/Proportion | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status: | |||

| Continuously married | 0.89 | 0–1 | |

| Divorced/separated/repartnered | 0.01 | 0–1 | |

| Death of either spouse | 0.06 | 0–1 | |

| Attrited | 0.04 | 0–1 | |

| Time-Invariant (Wave 1) | |||

| Marital Quality: | |||

| Low enjoyment | 0.19 | ||

| Average enjoyment together | 3.16 | 0.59 | 1–4 |

| Wives’ enjoyment together | 3.11 | 0.72 | 1–4 |

| Husbands’ enjoyment together | 3.23 | 0.64 | 1–4 |

| Spousal Homogamy: | |||

| Husband’s age | 56.81 | 5.11 | 25–83 |

| Age difference (Husband-Spouse) | 3.81 | 5.13 | −30–36 |

| Ethnoracial characteristics | |||

| Both spouses nonwhite | 0.10 | 0–1 | |

| Race discordant | 0.03 | 0–1 | |

| Both spouses white | 0.87 | 0–1 | |

| Husband education (years) | 12.96 | 3.25 | 0–17 |

| Education difference | 0.18 | 2.65 | −13–11 |

| Household wealth in 1992: | |||

| Low wealth (<50,000 USD a) | 0.16 | 0–1 | |

| Low-middle wealth (50,000–99,999 USD) | 0.18 | 0–1 | |

| Upper-middle wealth (100,000–249,999 USD) | 0.33 | 0–1 | |

| Upper wealth (≥250,000 USD) | 0.33 | 0–1 | |

| Marital Biography: | |||

| Remarried (yes = 1) | 0.27 | 0–1 | |

| Marital duration | 27.77 | 10.84 | 0.10–53.20 |

| Time-Varying (Waves 1–14) | |||

| Acquired Disability: | |||

| Husband acquired disability | 0.07 | 0–1 | |

| Wife acquired disability | 0.08 | 0–1 | |

| At least one spouse acquired disability | 0.14 | 0–1 | |

| Household income (Logged) | 10.82 | 1.02 | 0–14.72 |

| Life Transitions: | |||

| Husband currently works (yes = 1) | 0.51 | 0–1 | |

| Empty nest (yes = 1) | 0.72 | 0–1 | |

| Self-Rated Health: | |||

| Husband’s self-rated health | 3.40 | 1.08 | 1–5 |

| Wife’s self-rated health | 3.54 | 1.04 | 1–5 |

| Proxy interview (Husband) | 0.10 | 0–1 |

| Gender-Specific Acquired Disability | Couple-Level Acquired Disability | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | |

| Marital Quality a | |||||

| Low enjoyment | 1.46 *** (0.17) | 1.56 *** (0.17) | 1.53 *** (0.17) | 1.46 *** (0.17) | 1.65 *** (0.17) |

| Acquired Disability b | |||||

| Husband disability | 0.34 (0.34) | 0.34 (0.33) | 0.81 * (0.40) | ||

| Wife disability | 0.56 † (0.30) | 1.05 ** (1.77) | 0.57 † (0.30) | ||

| Couple-level disability | 0.49 † (0.26) | 1.07 *** (0.30) | |||

| Interaction Terms | |||||

| Low Enjoyment*Husband ADL | −1.13 (0.69) | ||||

| Low Enjoyment*Wife ADL | −1.12 † (0.58) | ||||

| Low Enjoyment*Couple ADL | −1.47 ** (0.50) | ||||

| Spousal Homogamy a | |||||

| Husband’s age | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) | −0.07 ** (0.02) |

| Age difference | 0.04 ** (0.02) | 0.04 ** (0.02) | 0.04 ** (0.02) | 0.05 ** (0.02) | 0.04 ** (0.02) |

| Ethnoracial Characteristics | |||||

| Both spouses nonwhite | −0.36 (0.24) | −0.36 (0.24) | −0.36 (0.24) | −0.35 (0.23) | −0.36 (0.24) |

| Different race/ethnicity | 0.58 * (0.29) | 0.57 * (0.29) | 0.58 * (0.29) | 0.58 * (0.29) | 0.57 * (0.29) |

| Husband education (years) | −0.00 (0.04) | −0.00 (0.04) | −0.00 (0.04) | −0.00 (0.04) | −0.00 (0.04) |

| Education difference | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) |

| Household wealth a | |||||

| Low wealth | 0.23 (0.25) | 0.23 (0.25) | 0.22 (0.25) | 0.23 (0.25) | 0.23 (0.25) |

| Low-middle wealth | −0.17 (0.26) | −0.18 (0.26) | −0.17 (0.26) | −0.18 (0.26) | −0.18 (0.26) |

| Upper-middle wealth | −0.24 (0.23) | −0.24 (0.23) | −0.23 (0.23) | −0.24 (0.23) | −0.23 (0.23) |

| Marital Biography | |||||

| Remarried | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.24 (0.24) | 0.23 (0.24) | 0.24 (0.22) | 0.24 (0.22) |

| Marital duration | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) | −0.04 *** (0.01) |

| Household income (Logged) b | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.03 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.07) | −0.04 (0.07) |

| Life Transitions b | |||||

| Husband currently works | −0.02 (0.19) | −0.02 (0.19) | −0.02 (0.19) | −0.02 (0.19) | −0.02 (0.19) |

| Empty nest | −0.10 (0.17) | −0.10 (0.17) | −0.10 (0.17) | −0.10 (0.17) | −0.09 (0.17) |

| Self-Rated Health b | |||||

| Husband’s health | −0.01 (0.07) | −0.01 (0.07) | −0.01 (0.07) | −0.00 (0.08) | −0.01 (0.08) |

| Wife’s health | −0.07 (0.08) | −0.07 (0.08) | −0.07 (0.08) | −0.08 (0.08) | −0.09 (0.08) |

| Proxy interview (Husband) b | −0.11 (0.26) | −0.11 (0.26) | −0.11 (0.26) | −0.10 (0.26) | −0.10 (0.26) |

| Period | −0.21 *** (0.03) | −0.21 *** (0.03) | −0.21 *** (0.03) | −0.21 *** (0.03) | −0.21 *** (0.03) |

| Intercept | 0.88 | 0.84 | 0.88 | 0.91 | 0.88 |

| Rao-Scott Likelihood Ratio | 40.24 *** | 38.57 *** | 38.52 *** | 42.38 *** | 40.64 *** |

| Degrees of Freedom | 61.51 | 64.39 | 64.39 | 58.76 | 61.68 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Latham-Mintus, K.; Holcomb, J.; Zervos, A.P. Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples? Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010027

Latham-Mintus K, Holcomb J, Zervos AP. Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples? Social Sciences. 2022; 11(1):27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010027

Chicago/Turabian StyleLatham-Mintus, Kenzie, Jeanne Holcomb, and Andrew P. Zervos. 2022. "Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples?" Social Sciences 11, no. 1: 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010027

APA StyleLatham-Mintus, K., Holcomb, J., & Zervos, A. P. (2022). Linked Lives: Does Disability and Marital Quality Influence Risk of Marital Dissolution among Older Couples? Social Sciences, 11(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010027