In Pursuit of Development: Post-Migration Stressors among Kenyan Female Migrants in Austria

Abstract

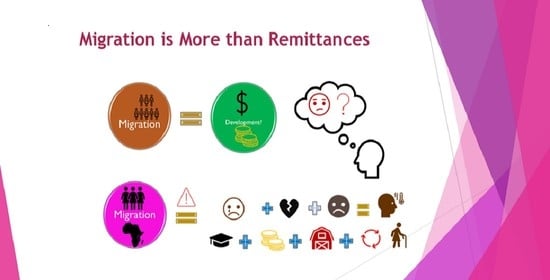

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Transnationalism and Social Support

2.2. Acculturative Stress

2.3. Discrimination and Racism

2.4. Insufficient Information

2.5. International African Female Migration

3. Theoretical Framework

4. Present Study

5. Methods

- What are the lived experiences of Kenyan female migrants in Austria?

- What are the coping strategies of Kenyan female migrants in Austria in dealing with acculturative stress?

5.1. Participants

5.2. Sample and Procedure

5.3. Data Collection

5.4. Data Analysis

6. Results

6.1. Troubled Relationships

I broke contact with my half-sister and my other sister too. Also, that my other sister broke contact with my half-sister. We still live in the same city, but we don’t really talk. I feel like our half-sister did a lot of damage to me and my sister because we always learn more to fight against each other. We experienced very bad things with our half-sister (…).

I wish I could have this with my real parents (…). I wish I could have the same relationship as other children, call my mother every day.

My parents were crying so hard, but they said it was good for our half-sister to help us. When we visited home, we didn’t want to go back to Austria (…) our half-sister was shouting and threatened to tear our passports.(Fadhila)

I actually thought of going home during that point. And I tried contacting people at home that I knew before I came to Europe and people had really changed. Nobody wanted to be associated with somebody who had been in Europe and didn’t make to stay there. So, you are in this dilemma: Ok, so in case, I do not get the papers, so what do I do now?

My mother was really mad at me. She could not understand why others have managed in Europe to come and build a house and build a comfortable life at home.(Tumaini)

We have not been able to maybe say we have made progress as our peers at home with lots of property.(Karimu)

The people at home were still expecting support from us. They could not understand. The people at home were like, “She is making our son not to send us any money. She is now controlling him.”

6.2. Unfulfilled Dreams

I was blaming myself for dragging my children into my failed dreams. I would call my friends or write to my former workmates in Kenya, they would tell me, “Oh we are doing this, we are doing that” and I thought, “What a waste of life! What really made me do this? What kind of a mistake was this?”

I expected by this time to have made lots of money. By this time, I expected to have tracts of land, to have invested, I expected to have an NGO by this time, I expected to have done great things.

I was a lecturer in Kenya. I came to Austria as an Au pair.(Baraka)

I was not trained for that position. This was also another hard, hard hill for me to climb.(Karimu)

One of my sons asked me, “Mummy you mean we were rich in Kenya?” and I said “What do you mean?” and he said, “But on Sundays, we would go after church, we would drive to town, go out to hotels, have meals, go swimming, we bought newspapers every day, you were driving your own car, daddy had his own car, we had a big house with a compound.” It really broke my heart; it really broke my heart.

My children were also suffering (..), they were seeing the difference, they noticed, and I cried a lot, I cried. I went into a depression (…) it was really a bad time. It was not good for my health even for my relationship with my husband. Then my mother passed away, and I sank into another kind of depression.

When the children came here, they had already gone backward in education for one year. They had lost one year.(Karimu)

6.3. Cultural Conflicts

Now the kids because of the influence, I don’t know what and our lack of understanding of the education system. I mean we kind of started losing them, it was too much for us, we were not able to catch up, to cope, to understand. I mean we were like illiterate parents, who didn’t know anything that is happening to the children.(Karimu)

We decided that the children have to go back home. We wanted them not to feel bad, so we took them to very expensive schools. It was really, really expensive. It was a time of being separated.

You know, I think certain things bring you close to God, so we prayed a lot. We trusted God to watch over them.

I am confused because I don’t know; here I’m a stranger and there (Kenya) I am a stranger because I don’t speak the language. I don’t have the feeling for the culture there because I never learnt to have these feelings.

6.4. Racism

I know that actually I’m here for a purpose, mostly because of the word of the Lord, which is my everything, yes, the word of the Lord, so I know that I’m here for a purpose.

It was very disturbing and when I was alone, I was thinking about it and saying, “I hate my skin colour. Why can’t I look like them?” I was always praying to God, “why can’t you change my skin colour.”

And he was like “Yeah, how much do you charge?” And I am looking at him wondering what is happening here. I am just waiting for my train.

You are rejected in many places, and you are not accepted and the racism. I was heartbroken because I was thinking that I would be accepted. I found people who didn’t accept me.(Neema)

They said, “Now you have to get out of the house.” When it comes to justice, when you are a foreigner, especially when you are black, you have no chance here. No chance! especially when it’s a white and a Black. They just listen to the whites and take only what the white one is saying.

What helped me very much not to break down, after all what I went through first was my faith. It played a part.

7. Discussion

8. Conclusions

9. Limitations

10. Implications and Recommendations for Further Research

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 1998. Linkages between internal and international migration: The African situation. International Social Science Journal 50: 387–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 2008. Migration in Sub Saharan Africa. Uppsala: The Nordic Africa Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Adepoju, Aderanti. 2011. Reflections on international migration and development in sub-Saharan Africa. African Population Studies 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Agadjanian, Victor. 2008. Research on International Migration within Sub-Saharan Africa: Foci, Approaches, and Challenges. The Sociological Quarterly 49: 407–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, Claire, and Susan Kirkpatrick. 2016. Narrative interviewing. International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy 38: 631–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Appleyard, Reginald Thomas. 1989. Migration and Development: Myths and Reality. The International Migration Review 23: 486–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atong, Kennedy, Emmanuel Mayah, and Akhator Odigie. 2018. Africa Labour Migration to the GCC States: The Case of Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria & Uganda. An. African Regional Organisation of the International Trade Union Confederation (ITUC-AFRICA). Available online: http://www.ituc-africa.org/IMG/pdf/ituc-africa_study-africa_labour_migration_to_the_gcc_states.pdf (accessed on 23 September 2019).

- Bakewell, Oliver. 2009. ‘Keeping Them in Their Place’: The ambivalent relationship between development and migration in Africa. Third World Quarterly 29: 1341–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bentley, Jacob A., John W. Thoburn, David Gage Stewart, and Lorin Debora Boynton. 2012. Post-Migration Stress as a Moderator between Traumatic Exposure and Self-Reported Mental Health Symptoms in a Sample of Somali Refugees. Journal of Loss & Trauma 17: 452–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John Widdup. 1997. Immigration, acculturation, and adaptation. Applied Psychology: An International Review 46: 5–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, John Widdup. 2001. A psychology of migration. Journal of Social Issues 57: 615–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertocchi, Graziella. 2016. The legacies of slavery in and out of Africa. IZA Journal of Migration 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodomo, Adams. 2014. A relative advantage. The World Today 70. Available online: https://www-proquest-com.uaccess.univie.ac.at/docview/1503121086?pq-origsite=primo (accessed on 17 May 2021).

- Bodomo, Adams. 2018. The Bridge is not Burning Down: Transformation and Resilience within China’s African Diaspora Communities. African Studies Quarterly 17: 63–83. [Google Scholar]

- Bodomo, Adams. 2020. Historical and contemporary perspectives on inequalities and well-being of Africans in China. Asian Ethnicity 21: 526–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromfield, Nicole. 2014. Interviews with divorced women from the United Arab Emirates: A rare glimpse into lived experiences. Families, Relationships and Societies 3: 339–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, Donn. 1969. Attitudes and attraction. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 4: 35–89. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, Christopher. 2019. “European Demographics and Migration.” Governance in an Emerging New World Winter Series (129). Available online: https://www.hoover.org/research/european-demographics-and-migration (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Cheeseborough, Thekia, Overstreet Nicole, and Monique L. Ward. 2020. Interpersonal Sexual Objectification, Jezebel Stereotype Endorsement, and Justification of Intimate Partner Violence Toward Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly 44: 203–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choma, Becky L., and Elvira Prusaczyk. 2018. The Effects of System Justifying Beliefs on Skin-Tone Surveillance, Skin-Color Dissatisfaction, and Skin-Bleaching Behavior. Psychology of Women Quarterly 42: 162–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collett, Elizabeth. 2015. The Asylum Crisis in Europe: Designed Dysfunction. Transatlantic Council on Migration. Brussels: Migration Poilicy Institute, Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/news/asylum-crisis-europe-designed-dysfunction (accessed on 20 October 2018).

- Collier, Paul. 2013. Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2007. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, John W. 2014. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches, 4th ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- de Haas, Hein. 2010. Migration and development: Theoretical perspective. International Migration Review 44: 227–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- DeGruy, Joy. 2017. Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome: America’s Legacy of Enduring Injury and Healing. Revised. Portland: Joy Degruy Publications Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Di John, Jonathan. 2011. Is There Really a Resource Curse?A Critical Survey of Theory and Evidence. Global Governance 17: 167–84. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/8a2d/868a1337310c20107ff8eb897dce5396ec85.pdf (accessed on 12 August 2019).

- Fesenmyer, Leslie. 2016. Deferring the Inevitable Return ‘Home’: Contingency and Temporality in the Transnational Home-Making Practices of Older Kenyan Women Migrants in London. In Transnational Migration and Home in Older Age. Edited by Kate Walsh and Lena Näre. London: Routledge, pp. 129–39. [Google Scholar]

- Flahaux, Marie-Laurence, and Hein De Haas. 2016. African migration: Trends, patterns, drivers. Comparative Migration Studies 4: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Jenny. 2018. Recognizing and Resolving the Challenges of being an insider Researcher in Work-integrated Learning. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 19: 311–20. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1196753.pdf (accessed on 22 July 2019).

- Fleury, Anjali. 2016. Understanding Women and Migration. A Literature Review. (Working Paper 8). Available online: https://www.knomad.org/publication/understanding-women-and-migration-literature-review-annex-annotated-bibliography (accessed on 11 June 2018).

- Geiger, Martin, and Antoine Pécoud. 2013. Migration, Development and the ‘Migration and Development Nexus’. Population Space and Place 19: 369–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Garcia, Jesus R., Ermal Hitaj, Montfort Mlachila, Arina Viseth, and Mustafa Yenice. 2016. Sub-Saharan African Migration: Patterns and Spillovers. IMF Elibrary. Washington DC: International Monetary Fund. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grotti, Vanessa, Cynthia Malakasis, Chiara Quagliariello, and Nina Sahraoui. 2018. Shifting vulnerabilities: Gender and reproductive care on the migrant trail to Europe. Comparative Migration Studies 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guest, Greg, Arwen Bunce, and Laura Johnson. 2006. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods 18: 59–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagen-Zanker, Jessica, and Marta Foresti. 2018. Harnessing Migration. The United Nations Association—UK. Available online: https://www.sustainablegoals.org.uk/about-una-uk/ (accessed on 8 August 2019).

- Hatton, Timothy J., and Jeffery G. Williamson. 1994. What Drove the Mass Migrations from Europe in the Late Nineteenth Century? Population and Development Review (Population Council) 20: 533–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Hendriks, Martijn, and David Bartram. 2019. Bringing Happiness Into the Study of Migration and Its Consequences: What, Why, and How? Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 17: 279–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Horvath, Kenneth, Anna Amelina, and Karin Peters. 2017. Re-thinking the politics of migration. On the uses and challenges of regime perspectives for migration research. Migration Studies 5: 301–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idemudia, Erhabor Sunday. 2014. Associations between demographic factors and perceived acculturative stress among African migrants in Germany. African Population Studies 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Idemudia, Erhabor, and Klaus Boehnke. 2020. Social Experiences of Migrants. In Psychosocial Experiences of African Migrants in Six European Countries. Cham: Springer, vol. 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM. 2019. Increased Number of Nigerian Migrants Fall Victim to Sex Trafficking, Exploitation in Mali. IOM Regional Office for West and Central Africa. Available online: https://www.iom.int/news/increased-number-nigerian-migrants-fall-victim-sex-trafficking-exploitation-mali (accessed on 17 July 2019).

- Jena, Farai. 2017. Migrant Remittances and Physical Investment Purchases: Evidence from Kenyan Households. The Journal of Development Studies 54: 312–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuiku, Jane. 2017. Immigrating to Northeast America: The Kenyan Immigrant’s Experience. Journal of Social, Behavioral and Health Sciences 11: 4–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagotho, Njeri. 2020. Towards Household Asset Protection: Findings from an Inter-generational Asset Transfer Project in Rural Kenya. Global Social Welfare 7: 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratzmann, Katerina, and Katharina Hartl. 2019. Common Home. Migration and Development in Austria. Vienna: Caritas Austria, Available online: https://www.caritas.at/fileadmin/storage/global/image/Kampagnen-nach-Jahren/MIND/CommonHome_Webversion.pdf (accessed on 2 July 2020).

- Kawar, Mary. 2004. Gender and migration: Why are women more vulnerable. In Femmes en Mouvement: Genre, Migrations et Nouvelle Division Internationale du Travail. Edited by Fenneke Reysoo and Christine Verschuur. Geneva: Graduate Institute Publications, pp. 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Krotofil, Joanna, and Dominika Motak. 2018. A critical discourse analysis of the media coverage of the migration crisis in Poland. The Religion and Ethnic Future of Europe, Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis 28: 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lumumba, Patrick. 2018. Available online: https://gads.univie.ac.at/fileadmin/user_upload/p_gads/Lumumba_speech.pdf. (accessed on 20 August 2018).

- Mafu, Lucas. 2019. The Libyan/Trans-Mediterranean Slave Trade, the African Union, and the Failure of Human Morality. SAGE Open 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Malit, Froilan, Jr., and Ali Al Youha. 2016. Kenyan Migration to the Gulf Countries: Balancing Economic Interests and Worker Protection. Migration Information Source; The Online Journal for Migration Policy Institute. Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/kenyan-migration-gulf-countries-balancing-economic-interests-and-worker-protection (accessed on 11 December 2019).

- Maymon, Paulina Lucio. 2017. The Feminization of Migration: Why are Women Moving More? Cornell Policy Review. Available online: http://www.cornellpolicyreview.com/the-feminization-of-migration-why-are-women-moving-more/ (accessed on 22 August 2018).

- Mbiti, John Samuel. 1969. African Religions and Philosophy. Oxford: Heinemann Educational Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Misati, Nyakerario Rosaline, Anne Kamau, and Hared Nassir. 2019. Do migrant remittances matter for financial development in Kenya? Financial Innovation 5: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, Matthias Johannes, and Eckhardt Koch. 2017. Gender Differences in Stressors Related to Migration and Acculturation in Patients with Psychiatric Disorders and Turkish Migration Background. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 19: 623–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Musangi, Pauline. 2017. Women Land and Property Rights in Kenya. Available online: https://land.igad.int/index.php/documents-1/countries/kenya/gender-3/621-women-land-and-property-rights-in-kenya-by-musangi-wb-conf-tool-453-paper-2017/file (accessed on 14 August 2018).

- Myers, Norman. 2005. Environmental Refugees: An Emergent Security Issue. In 13th Economic Forum 23–25 May. Vienna: Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, Available online: www.osce.org/documents/e69ea/2005/05/14488_en.pdf (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Nwoye, Augustine. 2009. Understanding and treating African immigrant families: New questions and strategies. Psychotherapy & Politics International 7: 95–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neil, Tam, Fleury Anjali, and Marta Foresti. 2016. Women on the Move: Migration, Gender Equality and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.odi.org/publications/10476-women-move-migration-gender-equality-and-2030-agenda-sustainable-development (accessed on 21 September 2018).

- Odera, Lillian. 2010. Kenyan Immigrants in the United States: Acculturation, Coping Strategies, and Mental Health. Elpaso: LFB Scholarly Publishing LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Ogude, James. 2018. Ubuntu and Personhood. Trenton: Africa World Press. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke-Ihejirika, Philomina, Sophie Yohani, Bukola Salami, and Natalie Rzeszutek. 2020. Canada’s Sub-Saharan African migrants: A scoping review. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onwuachi-Willig, Angela. 2016. The Trauma of the Routine: Lessons on Cultural Trauma from the Emmett Till Verdict. Sociological Theory 34: 335–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orozco, Manuel, and Jenna Hennebry. 2017. Migration, Remittances and Financial Inclusion: Challenges and Opportunities for Women’s Economic Empowerment. Global Migration Group, Economic Empowerment. New York: UN Women, Available online: http://www.globalmigrationgroup.org/system/files/GMG_Report_Remittances_and_Financial_Inclusion_updated_27_July.pdf (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Phinney, Jean S., Gabriel Horenczyk, Karmela Liebkind, and Paul Vedder. 2001. Ethnic Identity, Immigration, and Well-Being:An Interactional Perspective. Journal of Social Issues 3: 493–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pietkiewicz, Igor, and Jonathan Alan Smith. 2014. A practical guide to using Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis in qualitative research psychology. Czasopismo Psychologiczne–Psychological Journal 20: 7–14. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/263767248_A_practical_guide_to_using_Interpretative_Phenomenological_Analysis_in_qualitative_research_psychology (accessed on 28 September 2018).

- Redfield, Robert, Ralph Linton, and Melville J. Herskovits. 1936. Memorandum for the Study of Acculturation. American Anthropologist 38: 149–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robila, Mihaela. 2017. Refugees and Social Integration in Europe. Division for Social Policy and Development. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. [Google Scholar]

- Rodney, Walter. 1973. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bolge L’Ouverture Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, Jonathan, and Mike Osborn. 2007. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis. Available online: http://med-fom-familymed-research.sites.olt.ubc.ca/files/2012/03/IPA_Smith_Osborne21632.pdf (accessed on 14 July 2019).

- Smith, Jonathan Alan, Paul Flowers, and Michael Larkin. 2009. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. London: Sage Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Mariam, Cindy-Lee Dennis, Michael Kariwo, Kaisy Eastlick Kushner, Nicole Letourneau, Knox Makumbe, and Edward Shizha. 2015. Challenges faced by refugee new parents from Africa in Canada. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 17: 1146–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, Jane, and Zubin Austin. 2015. Qualitative Research: Data Collection, Analysis, and Management. Canadian Journal of Hospital Pharmacy 68: 226–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Taylor, Georgina, Jane Wangaruro, and Irena Papadopoulos. 2012. It Is My Turn To Give’: Migrants’ Perceptions of Gift Exchange and the Maintenance of Transnational Identity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 7: 1085–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, Rebecca, and Lindsey Carte. 2016. Migration and Development? The Gendered Costs of Migration on Mexico’s Rural “Left Behind”. Geographical Review 106: 399–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tousignant, Michel, and Nibisha Sioui. 2009. Resilience and Aboriginal Communities in Crisis: Theory and Interventions. Journal of Aboriginal Health 5: 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tutu, Desmond. 2013. Who We Are: Human Uniqueness and the African Spirit of Ubuntu. Desmond Tutu, Templeton Prize 2013. Templeton Prize. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0wZtfqZ271w (accessed on 1 June 2019).

- UN. 2020. UN Chief in ‘Support Migrants’ Plea, as Remittances Drop by 20 per cent Predicted. United Nations. Available online: https://news.un.org/en/tags/international-day-family-remittances (accessed on 15 June 2020).

- Van Breda, Adrian. 2018. A Critical Review of Resilience Theory and its Relevance for Social Work. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hout, Marie-Claire, and Mayyada Wazaify. 2021. Parallel discourses: Leveraging the Black Lives Matter movement to fight colorism and skin bleaching practices. Public Health 192: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wangaruro, Jane. 2011. I Have Two Homes: An Investigation into the Transnational Identity of Kenyan Migrants in the United Kingdom (UK) and How this Relates to Their Wellbeing. Ph.D. Thesis, Middlesex University, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wodak, Ruth, and Markus Rheindorf. 2018. Borders, Fences, and Limits—Protecting Austria From Refugees: Metadiscursive Negotiation of Meaning in the Current Refugee Crisis. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies 16: 15–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, Roberta Lynn, David Shiyokha Busolo, Maryann Crockett, Ruth Anne Dean, Miriam R. Amaladas, and Pierre J. Plourde. 2017. A qualitative study on African immigrant and refugee families’experiences of accessing primary health care services in Manitoba, Canada: It’s not easy! International Journal for Equity in Health 16: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Yohani, Sophie, and Philomena Okeke-Ihejirika. 2018. Pathways to help-seeking and mental health service provision for African female survivors of conflict-related sexualized gender-based violence. Women & Therapy 41: 380–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zara. 2017. Anti Racism Report 2017. Vienna: Zara: Zivilcourage und Anti-Rassismus-Arbeit, Available online: https://zara.or.at/ (accessed on 22 August 2020).

- Zara. 2018. Anti Racism Report 2018. Vienna: ZARA—Civil Courage & Anti-Racism Work, Available online: https://assets.zara.or.at/download/pdf/ZARA-Rassismus_Report_2018_EN.pdf (accessed on 21 August 2020).

- Zlotnik, Hania. 2004. International Migration in Africa: An Analysis Based on Estimates of Migration Stock. Washington, DC: Migration Policy Institute, Available online: https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/international-migration-africa-analysis-based-estimates-migrant-stock (accessed on 11 June 2019).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Stuhlhofer, E.W. In Pursuit of Development: Post-Migration Stressors among Kenyan Female Migrants in Austria. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010001

Stuhlhofer EW. In Pursuit of Development: Post-Migration Stressors among Kenyan Female Migrants in Austria. Social Sciences. 2022; 11(1):1. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010001

Chicago/Turabian StyleStuhlhofer, Eunice Wangui. 2022. "In Pursuit of Development: Post-Migration Stressors among Kenyan Female Migrants in Austria" Social Sciences 11, no. 1: 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010001

APA StyleStuhlhofer, E. W. (2022). In Pursuit of Development: Post-Migration Stressors among Kenyan Female Migrants in Austria. Social Sciences, 11(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11010001