Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods and Materials

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Data Collection

2.2.1. Quantitative Data Collection

2.2.2. Qualitative Data Collection

2.2.3. Study Population

2.3. Measures

Sampling Technique

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Quantitative Analysis

3.2. Qualitative Analysis

4. Relative Deprivation Theory

5. Conceptual Clarifications

5.1. Youth

5.2. Security in Nigeria

5.3. Youth Violence in Nigeria

6. Discussion

6.1. Sociopolitical and Economic Causes of Youth Violence in Nigeria

6.2. Theoretical Linkages with Violence

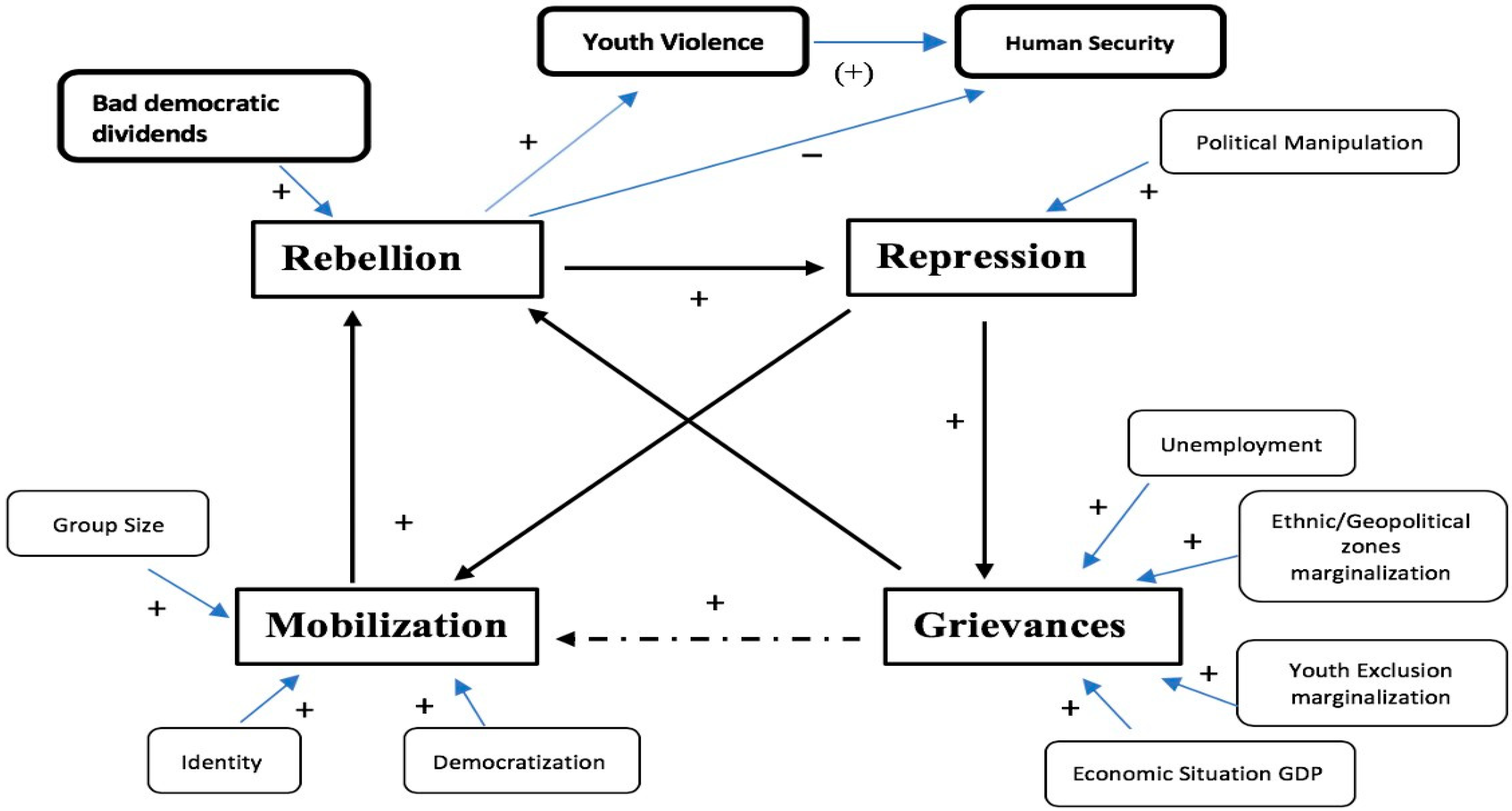

Adjusted RD Model

6.3. Security Implications of Youth Violence

6.4. Policy Recommendation: Curbing Violence and Improving Human Security

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbo, Usman, Zawiyah M. Zain, and Bashir A. Njidda. 2017. The Almajiri System and Insurgency in the Northern Nigeria: A Reconstruction of the Existing Narratives for Policy Direction. International Journal of Innovative Research and Development 6: 346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adah, Benyin Akomaye, and Ugochukwu David Abasilim. 2015. Development and its Challenges in Nigeria: A theoretical Discourse. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aderinto, Adeyinka Abideen, and Agbola Tunde. 1994. International symposium on Urban Management and Urban Violence in Africa held at Ibadan, November 7–11, IFRA (French Institute for Research in Africa). In Students Unrest and Urban Violence in Nigeria in Urban Management and Urban Violence in Africa. Ibadan: IFRA. [Google Scholar]

- African Youth Charter. 2006. Vision and Mission. Available online: https://au.int/en/treaties/african-youth-charter (accessed on 12 October 2020).

- Ajaegbu, Okechukwu. 2012. Rising youth Unemployment and Violent Crime in Nigeria. American Journal of Social Issues and Humanities 2: 315–21. [Google Scholar]

- Akpan, Dominic A. 2015. Youth’s Unemployment and Illiteracy: Impact on National Security, the Nigerian Experience. International Journal of Arts and Humanities (IJAH) 4: 14. [Google Scholar]

- Alemika, Etenabi, and Innocent Chukwuma. 2000. Police-community Violence in Nigeria. Abuja: Centre for Law Enforcement Education and National Human Right Commission. [Google Scholar]

- Anasi, Stella Ngozi. 2010. Curbing youth Restiveness in Nigeria: The Role of Information and Libraries. Library Philosophy Practice Journal, 1–7. Available online: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/388/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Awogbenle, Cyril, and Kelechi Chijioke Iwuamadi. 2010. Youth Unemployment: Entrepreneurship Development Programme as an Intervention Mechanism. African Journal of Business Management 4: 831–35. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, David A. 1997. The concept of security. Review of International Studies 23: 5–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouchat, Clarence J. 2010. Security and Stability in Africa: A Development Approach. Retrieved 24 July 2020. Available online: https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pubs/display.cfm?pubID=964 (accessed on 10 January 2018).

- Buzan, Barry, and R. J. Barry Jones. 1981. Change and the Study of International Relations: The Evaded Dimension. London: Frances Pinter. [Google Scholar]

- Caldeira, Teresa Pires. 2000. Cidade de Muros: Crime, Segregação e Cidadania em São Paulo. Available online: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0104-93132002000100010 Portugal (accessed on 14 January 2018).

- Cincotta, Richard, Robert Engelman, and Daniele Anastasion. 2003. The Security Demographic: Population and Civil Conflict After the Cold War. ECSP Report. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/updates?advanced-search=%28S1907%29 (accessed on 10 January 2018). [CrossRef]

- Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigerian. 1999. Available online: http://www.nigeria-law.org/ConstitutionOfTheFederalRepublicOfNigeria.htm (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Cramer, Christopher. 2011. Unemployment and Participation in Violence. Washington, DC: World Bank. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/9247 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO (accessed on 10 July 2021).

- Crawford, Victoria. 2012. Security concerns in Africa. In Security and Africa: An Update, a Collection of Essays on Developments in the Field of Security and Africa since the UK Governments 2010 Strategic. Edited by P. Smith. Defense and Security Review. UK: Africa All Party Parliamentary Group. [Google Scholar]

- Dicristina, Bruce. 2016. Durkheim’s theory of anomie and crime: A clarification and elaboration. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology 49: 311–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbeleye, Oluwatoba Samuel. 2005. Recreational Facilities in Schools: A Panacea for youths’ Restiveness. Journal of Human Ecology 18: 93–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. 2009. Youth in Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-statistical-books/-/KS-78-09-920?inheritRedirect=true (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- Francis, David. 2006. Peace and Conflict Studies: An African Overview of Basic Concepts. In Introduction to Peace and Conflict Studies in West Africa. Edited by Best Shedrack Gaya. Ibadan: Spectrum. [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda-Parr, Sakiko, and Carole Messineo. 2012. Human Security: A Critical Review of the Literature. Working Paper. Leuven: Centre for Research on Peace and Development Belgium, vol. 11, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Furlong, Andy. 2013. Youth studies: An introduction. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gboyega, Ilusanya. 2005. Cultism and violent behaviours in tertiary institutions in Nigeria. Zimbabwe Journal of Educational Research 17: 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kpae, Gbenemene, and Eric Adishi. 2017. Community Policing in Nigeria: Challenges and Prospects. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research 3: 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Giles, Jane. 2013. Ingroups and Outgroups. In Inter/Cultural Communication: Representation and Construction of Culture. Edited by Anastacia Kurylo. New York: Sage Publications. Inc., pp. 140–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, Maria, Barbara Yoxon, Soitirios Karampampas, and Luke Temple. 2017. Relative deprivation and inequalities in social and political activism. Acta Politica 54: 398–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greif, Avner. 2006. Institutions and the Path to the Modern Economy: Lessons from Medieval Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gurr, Ted Robert. 1971. Why Men Rebel. Princeton: Pricenton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Henrik, Urdal. 2014. The Devil in the Demographics: The Effect of Youth Bulges on Domestic armed Conflict, 1950–2000. Social Development Papers, Conflict Prevention and Reconstruction. No. CPR 14. Washington, DC: World Bank Group. Available online: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/794881468762939913/The-devil-in-the-demographics-the-effect-of-youth-bulges-on-domestic-armed-conflict-1950-2000 (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Igbo, Harriet, and Innocent Ipka. 2013. Causes, Effects and Ways of Curbing youth Restiveness in Nigeria: Implications for Counselling. Journal of Education and Practice 4: 131–37. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, Oye A. 2014. National Development Strategies: Challenges and options. International Journal of Humanities and Social Science Invention 3: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Kahl, Colin. 1998. Constructing a separate peace: Constructivism, collective, liberal identity and democratic peace. Security Studies 8: 94–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Security Agencies Act. 1986. National Security Agencies Act (Nigeria). Available online: https://nlipw.com/national-security-agencies-act/ (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Nolte, Insa. 2004. Identity and Violence: The Politics of youth in Ijebu-Remo, Nigeria. The Journal of Modern African Studies 42: 61–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, Douglas, John Joseph Wallis, and Barry Weingast. 2009. Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Obgbeide, Francis Oluwaseun. 2013. Youths’ Violence and Electoral Process in Nigeria’s Fourth Republic: A case study of OTA, Ogun State Nigeria. International Journal of Education and Research 1: 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Obiakor, Nwachukwu. 2016. History, land and conflict in Nigeria: The Aguleri-Umuleri experience, 1933–1999. UJAH: Unizik Journal of Arts and Humanities 17: 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okeshola, Folashade, and Patience Mudaire. 2013. Community Policing in Nigeria: Challenges and Prospects. American International Journal of Contemporary Research 3: 134–38. [Google Scholar]

- Okonofua, Benjamin. 2016. The Niger Delta Amnesty Program. NewYork: SAGE Open, p. 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okonta, Ike. 2012. The Fire Next time: Youth, Violence and Democratisation in NorthernNigeria. New Centre for Social Research. Berlin: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung. [Google Scholar]

- Onwuka, Ebele Mary, Kelechi Ugwu, and Ejike Daniel Chukwuemeka. 2015. Implications of youth unemployment and violent crime on the economic growth, a case study of Anambra state, Nigeria. Australian Journal of Commerce Study, 10–21. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3660350 (accessed on 11 July 2021).

- Oruwari, Yomi, and Owei Opuenebo. 2006. Youth in urban violence in Nigeria: A case study of urban gangs from Port Harcourt. In Niger Delta Economies of Violence, Project Working Paper. Washington, DC: United State Institute of Peace. [Google Scholar]

- Owolabi, Olayiwola, and Iwebunor Okwechime. 2007. Oil and security in Nigeria: The Niger Delta Crisis. Africa Development 32: 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, Axel West. 2004. Inequality as Relative Deprivation: A Sociological Approach to Inequality Measurement. Acta Sociologica 47: 31–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, Clare. 2011. Relative Deprivation Theory in Terrorism: A Study of Higher Education and Unemployment as Predictors of Terrorism. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Relative-Deprivation-Theory-in-Terrorism%3A-A-Study-Richardson/8cde665bbd27872a4a920b08e9f2774a5cd87d12 (accessed on 13 October 2019).

- Steffgen, Georges, and Norbert Ewen. 2007. Teachers as Victims of Violence School-The Influence of Strain and Culture School. International Journal on Violence and Schools 3: 81–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tenuche, Marietu. 2009. Youth Restiveness and Violence in Nigeria: A case study of youth Unrest in Ebiraland. Medwell Journals. The Social Sciences 4: 549–56. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, John. 1989. Deprivation and Political Violence in Northern Ireland, 1922–1985: A Time-Series Analysis. The Journal of Conflict Resolution 33: 676–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uduabo, Philips Uvumgah. 2019. Security Management and Private Security Outfits in Nigeria. International Journal of Social Sciences and Management Research 5: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Ukeje, Charles. 2005. Youths, Violence and the Collapse of Public Order in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Africa Development 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ukeje, Charles Ugochukwu, and Akin Iwilade. 2012. A Farewell to Innocence? African Youth and Violence in the Twenty-First Century. International Journal of Conflict and Violence 6: 339–51. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Habitat. 2012. UN Habitat for a Better Urban Future. Available online: https://unhabitat.org/urban-themes/youth/ (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- United Nations Population Fund. 2019. Youth Participation & Leadership. Available online: http://www.unfpa.org/youth-participation-leadership (accessed on 12 October 2019).

- United Nations. 1981. Secretary-General’s Report to the General Assembly A/36/215. Secretary-General’s Report to the General Assembly A/36/215. rep (Publication). New York: United Nations. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 1994. Human Development Report. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ezemenaka, K.E. Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070267

Ezemenaka KE. Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(7):267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070267

Chicago/Turabian StyleEzemenaka, Kingsley Emeka. 2021. "Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria" Social Sciences 10, no. 7: 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070267

APA StyleEzemenaka, K. E. (2021). Youth Violence and Human Security in Nigeria. Social Sciences, 10(7), 267. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10070267