Abstract

The purpose of this study is to establish the prevalence of barriers to women’s leadership in the family business in terms of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect, and sexism. We conduct eight semi-structured interviews with women holding leading managerial roles in family businesses in Mexico to identify the factors that impede/facilitate their involvement. We apply the theory of planned behavior (TPB) in order to determine how these factors support/constrain women in their roles. We find that some factors and circumstances are critical for women to achieve an important leadership role in the family business. These factors entail levels of education and experience, the extent to which women participate in strategic decision making and governance of the firm, as well as the support of the company’s founder and other family members for these women’s efficacy and self-esteem. These results challenge some of the extant findings in the literature, thus enriching the current perspectives on the leadership role of women in family firms. Moreover, this research is the first attempt to analyze impediments to women under the TPB perspective as well as one of the few studies conducted on the topic in Latin America, specifically in Mexico.

1. Introduction

Recognition of women in the leadership of family firms is increasing and has been evidenced by the rising proportion of female managers in family businesses (Barrett and Moores 2009; Humphreys 2013). It is estimated that women run 33 percent of family businesses in the United States (Sonfield and Lussier 2012). In Latin America, 90 percent of all enterprises are family owned or controlled (Borkowski 2001; Carraher 2005; Trevinyo-Rodríguez 2009, 2010), with many being led by women. In fact, a study by The Economist (2004) estimates that up to 95 percent of businesses in Mexico are family owned and led, providing a foundation of the country’s economy. This creates a large scope for leadership opportunities available to female family members. However, there is a considerable number of factors impeding women in Mexico reaching leading roles in family firms.

The purpose of this research is to examine the factors that influence female leadership in family businesses in terms of three different barriers: invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism. This is a contribution per se, since research on women in the family business is fragmented and usually approached from any of these three perspectives. We investigate all three barriers since each is associated with a particular set of cultural, social, behavioral and attitudinal factors, which, in turn, are considered obstacles on women’s path to leadership in the family business (e.g., Goffee and Scase 2015; Veale and Gold 1998). This gives us a broader perspective on obstacles underlining women’s progression to leadership in family firms. Moreover, in this study, we align this perspective with the theory of planned behavior (TPB) by Ajzen (1985, 1991) in order to further determine their impact on women’s final intentions to achieve and consolidate a leadership position in their family business.

To do so, we conduct a qualitative multi-case study involving eight semi-structured interviews, each with a female respondent who performs some form of managerial and leadership duties in their family firms. In this way, the present work contributes to the scarce literature on women’s involvement in family firms in Mexico, providing unique results tailored to the cultural settings of this country. Mexico is an interesting country to undertake this work because, on the one hand, there are strong cultural traditions that would make it harder for women to attain leadership positions in family businesses. However, on the other hand, being an emerging economy with most businesses being family led, many of those beliefs and values are being challenged and questioned.

We find that certain factors, such as a particular leadership style or inadequate remuneration, are less pervasive than documented in other studies. In contrast, levels of education and experience promote women’s integration, and facilitate their involvement in the strategic decision-making processes in the firm. Interestingly, the factors that women consider crucial for their career progression are recognition and support of other family members and of the owner in particular. Indeed, the support of the business owner is especially important, since it determines women’s suitability for business succession, and with time, it empowers them in their role.

Despite these interesting results, our examination provides mixed evidence of the importance of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism for women’s leadership, with some factors supporting the existence of these barriers in family businesses and others refuting them.

The present paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we review the literature closely related to female leadership and the participation of women in the family business in terms of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism. This will enable us to uncover the factors affecting the women’s intentions to lead the business. In Section 3 and Section 4, we present the conceptual framework and the methodological approach adopted in the present investigation, which focuses on a qualitative multi-case study. In Section 5, we provide a discussion of the results of the analysis, contrasting them with the existing findings in the literature. In Section 6, we provide our conclusions of the present study, including its limitations and new promising lines of research.

2. Literature Review

The involvement of women in family businesses has been studied extensively, with the number of research studies devoted to this topic doubling in the last decade (Campopiano et al. 2017). In this study, we examine how barriers associated with invisibility, the glass ceiling effect, and sexism influence women’s decision to lead a family business. Specifically, we start our discussion with sexism since various aspects of this barrier are the driving forces behind invisibility and the glass ceiling effect. Then we frame these perspectives within the theory of planned behavior (TPB).

2.1. Sexism

Sexism comprises discriminatory practices against women based on gender theory that can be either overt or subtle (Benokraitis 1997; Swim and Cohen 1997). Recognizably, nuanced or subtle forms of sexism are harder to detect but they are more frequent. This subtler form of sexism infiltrates education, politics, religion, law, and other areas that may have an influence on women’s succession in family businesses (Overbeke et al. 2013), and often drives invisibility and the glass ceiling effect.

Overbeke et al. (2015) argue that perhaps the most valid evidence of the gender bias in the context of family businesses is the negative relationship between fathers’ beliefs about a daughter’s expressive behaviors and her succession. “Expressiveness”, in comparison with “instrumentality”, encloses caring, nurturing, and other qualities that are more suitable for domestic duties (Spence and Buckner 2000; Judge and Livingston 2008; Mueller and Dato-On 2008). Instrumentality refers to “getting tasks done”, which suits professional roles in economic organizations (Mueller and Dato-On 2008; Spence and Buckner 2000). However, Overbeke et al. (2015) also argue that the perception that parents’ (mainly fathers) and daughters’ share of female self-efficacy has a significant influence on the aspirations (vision) and possibilities that women have for succession/leadership in the business.

Studies based on the contingency theory of leadership have tried to disentangle the different roles that women assume in leadership positions in the family business. Explicitly, Nekhili et al. (2018) indicate two positions, CEO and Chair leadership posts, which are aligned with different management styles for men and women assuming these positions. Specifically, having women as Chairs of a Board is more relevant for family firms than for non-family firms. A transformational leadership, as opposed to a transactional leadership style, is understood as a style of governance where leaders may disseminate the values and other elements of the family culture more effectively (Arzubiaga et al. 2018; Vallejo 2008, 2009).

In contrast, a transactional leadership style exhibited by women CEOs is needed in dealing with everyday tasks (Gabrielsson et al. 2007) and helps exert their authority and legitimate power in the firm. Furthermore, Songini and Gnan (2014) find evidence that even though family firms foster female involvement in governance and managerial roles, women do not seem to influence the adoption of managerial mechanisms when they reach leadership positions.

While the socio-emotional role played by women might be thought of as a reason for weakening their position in family firms (and in turn, for reducing women’s visibility as leaders), the value that family firms attach to this type of socio-emotional goals may actually provide an advantage for women (Salganicoff 1990; Dugan et al. 2008). Consequently, the caring, sensitive and nurturing nature of women, which is usually the cause of their invisibility in the family firm, may actually be of a great advantage to the business.

2.2. Invisibility

The cultural tradition in many countries has coined the notion of “invisibility”, which poses that women’s role in the family business is seldom acknowledged (Cole 1993, 1997). This is mainly attributed to the overlap of family and business issues in the firm, where the position and relational dynamics of women are transferred to the business context (Cesaroni and Sentuti 2014). According to Cole (1993), women’s work and efforts often remain unappreciated because they normally take on roles of assistants, informal advisers or mediators between members of the family who formally run the company (Francis 1999; Gillis-Donovan and Moynihan-Bradt 1990). As a result, women are normally underpaid or do not receive any remuneration for their work (Cole 1993; Francis 1999; Gherardi 2015; Gillis-Donovan and Moynihan-Bradt 1990; Hollander and Bukowitz 1990; Rowe and Hong 2000; Salganicoff 1990).

Women’s succession and involvement in the family firm might be further constrained by their wish to raise a family (Cadieux et al. 2002). Thus, unlike men, women face a difficult role conflict between their roles of mothers and wives on the one hand and their professional role in the family firm on the other (Dumas 1990; Hollander and Bukowitz 1990). Thus, in terms of succession, the work–family conflict reduces women’s chances to take over the family business (Curimbaba 2002; Dumas 1990, 1992, 1998; Goldberg and Wooldridge 1993; Haberman and Danes 2007; Keating and Little 1997; Vera and Dean 2005).

Cesaroni and Sentuti (2014) argue that the ‘invisibility’ of women in family enterprises might not be exclusively attributed to gender discrimination. Women’s personal choices are equally important as they lead them to accept a specific profile instead of another. In support of this, Gherardi and Perrotta (2016) studied gender legitimacy in family business succession by examining the co-presence of daughters in family business in two orders of worth—the industrial and the domestic—and found that inequality in the succession process is justified by daughters by shifting from one order of worth to the other.

However, a factor that may be considered as a potential advantage for women’s desirability of becoming a business leader is a range of intangible benefits that family firms offer. This includes security, flexibility, a supportive environment, and an “unhostile area for preparation” (Cromie and O’Sullivan 1999; Dumas 1992, 1998; Frishkoff and Brown 1993; Guo and Werner 2016; Haynes et al. 1999; Salganicoff 1990; St-Arnaud and Giguère 2018).

2.3. The Glass Ceiling Effect

The glass ceiling effect, also developed by Cole (1997), suggests the presence of high barriers for women wanting to hold top management positions, founded on gender differences. Although family firms should be an adequate environment for glass ceiling eradication for women belonging to the owner’s family, the presence of a glass ceiling in these firms is still recognized (Songini and Dubini 2003; Songini and Gnan 2014).

Among the drivers of the glass ceiling effect that impede access to senior or leadership positions in the family, factors related to the lack of founders’ trust and inadequate management competences should be distinguished. In addition, the acceptance of a new business leader is conditional on the candidate’s merits. Indeed, one of the common factors reducing women’s chances for progression to the leadership role in the succession process is their lack of adequate competencies, including education, experience and type of industrial sector (Roffey et al. 1996).

Among the hurdles that impede access to senior or leadership positions in the family, one can also mention factors related to the lack of early socialization of women into the family business, the lack of founders’ trust and inadequate management competences. Specifically, some authors (Iannarelli 1992; Poza and Messer 2001) draw attention to the aspect of introducing a child to the firm’s processes. They find that females are not made acquainted with the firm during childhood; consequently, this encourages them to seek a career outside the family business.

In less frequent cases when women succeed to make a professional career within the family business, they tend to attract more scrutiny (Barnes and Kaftan 1990; Dumas 1989). Kram and Hampton (1998) support this idea by explaining that women’s style of leadership and preparation often differs from that of men, which makes women more subject to distrust.

Other studies of the glass ceiling effect suggest that women’s succession process is smoother when a father and a daughter are involved (Martinez Jiménez 2009). This is simply because daughters are likely to be less competitive than sons (Galiano and Vinturella 1995; Haberman and Danes 2007) and because their relationship with their fathers is also likely to be more harmonious (Dumas 1989, 1992; Smythe and Sardeshmukh 2013). Interestingly, a study by Allen and Langowitz (2003) comparing family firms led by women and by men reports the opposite, with women having greater chances to become a successor to a female boss.

Undoubtedly, as Cole (1997) argues, more opportunities received by women in the egalitarian societies lead to an increase in their level of skills, education and experience. In turn, these help to smoothen the path of women towards top positions in their family firms (Aronoff 1998; Hisrich and Fülöp 1997; O’Connor et al. 2006; Salganicoff 1990) Additionally, women have been gradually occupying roles in sectors traditionally regarded as masculine; e.g., construction (Dumas 1992, 1998; Frishkoff and Brown 1993; Haynes et al. 1999; Lyman et al. 1985). This proves that certain factors can reduce the impact of the glass ceiling effect on women’s career in the family firm.

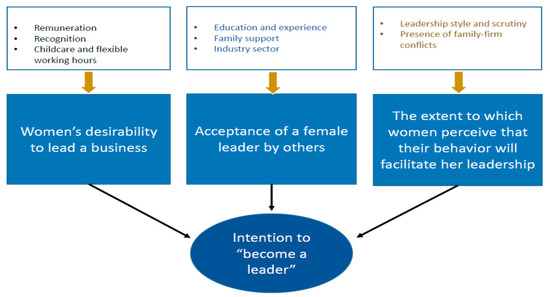

Given the review of factors affecting women’s leadership in family firms, we have grouped them according to the barrier they represent. Consequently, invisibility provides support of factors, such as inadequate remuneration, unrecognized effort, and inflexible working arrangements. The glass ceiling effect is consistent with the lack of education, experience, and family support and the type of industry sector. In contrast, sexism manifests itself in an inappropriate leadership style and the presence of a family–firm conflict. The relationship between these barriers and women’s intention to lead a business is analyzed in the TPB model.

3. Conceptual Framework

The theory of planned behavior (TPB) by Ajzen and Fishbein (1980) and Ajzen (1985, 1991) has been developed to predict how likely an individual is to engage in a particular behavior at a given time and place. Specifically, the likelihood of behaving in a particular way is generated by three different factors (beliefs) that affect the individual’s intention to perform the behavior. These factors include attitudes (the individual’s beliefs about the behavior), subjective norms (the individual’s beliefs about other people’s attitudes toward the behavior) and a perceived behavioral control (the individual’s beliefs about conforming to the planned behavior). Consequently, achieving a particular behavior by an individual depends on her own and others’ attitudes, as well as on her ability to enact the behavior. We must recognize other attempts to explain behavior of female leadership in the family business. See, for example, Nelson and Constantinidis (2017), who use the expectation states theory to consider the influence of societal, family, and group gender dynamics on succession. However, their work remained only at a conceptual level.

Leading a Family Firm as Planned Behavior

We analyze women’s intention to take up the leadership position in the TPB framework by examining their beliefs concerning the degree to which they favorably evaluate rising to the leader position; other family members’ acceptance of this fact; and these females’ perception that the behavior they exhibited had led to the desired outcome. These beliefs approximate attitudes, subjective norms and a perceived behavioral control in terms of leading the family firm. More importantly, these beliefs are influenced by invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism. We address the following research questions (RQ):

- Research Question 1. How do the factors embedded into the barriers of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism affect a woman’s desirability to lead a family business?

- Research Question 2. How do the factors embedded into the barriers of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism affect others’ acceptance of the woman’s leadership in the family firm?

- Research Question 3. How do the factors embedded into the barriers of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism affect a woman’s perception about having the capacity to become a leader of the family business?

Figure 1 summarizes the conceptual framework of this research:

Figure 1.

The influence of factors embedded into invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism on women’s intention to lead the family business in the theory of planned behavior model (Source: Authors).

4. Methodology

4.1. Sample

We follow a research strategy based on an exploratory and descriptive study, using a multi-case study analysis (De Massis and Kotlar 2014; Eisenhardt 1989; Eisenhardt and Graebner 2007; Yin 1994). We believe that a case study approach, which is firmly grounded in a positivist tradition (Reay 2014), is the appropriate research strategy. This enables us to undertake a detailed contextual analysis of a number of factors exploring the impact of the three barriers (invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism) on women’s leadership participation in their family business, as modelled by TPB. An exploratory-descriptive case study allows us to unravel which theoretical propositions are relevant (Bitektine 2008; De Massis and Kotlar 2014; Pratt 2009).

We decided to use a convenience sample, so that we selected only businesses where the same family or related families possess at least 51% ownership, where at least one family member occupies an executive position, and where there is a declared willingness to preserve the firm within the family (Chua et al. 1999). In addition, the selected firms have been in operation for at least ten years and at least one female family member has been involved in the succession process. As our focus is to explore factors that impede women’s raise to a leadership position in a family firm, we purposefully selected only participants who have already held a position of considerable responsibility and could share retrospectively their experience of obstacles in their journey of progression within their family firm. We acknowledge that it would also be interesting to consider the opinions of women who do not aspire to lead the family business; however, this investigation is beyond the scope of the present study, where the focus is on obstacles to women’s leadership. We also ensured that we did not exclusively include cases where the relation of women family members to the founder/main proprietor only as daughters, but also as spouses or siblings.

The cases were obtained from the 2017 National Statistical Directorate of Business Entities1 in Mexico. Among the eight cases, four accounted for situations where the owner’s daughter was a potential candidate for becoming the business leader, three cases included wives, and only one represented the case of the owner’s sister.

4.2. Data Collection

We collected the data by conducting face-to-face interviews. In all cases, the women were the key informants. Additionally, in five cases, it was possible to interview the founder too, as a measure to triangle the information and reduce common method variance (Chang et al. 2010).

The interviews were semi-structured, with each interview session lasting between one and two hours. The interviews were conducted on each family firm’s premises during May 2017; audio and video recordings were created and transcribed. An interview protocol was employed to facilitate the interview process and questions were designed to elicit rich narratives highlighting factors influencing women’s involvement and leadership in family businesses. The specific questions used in the interview protocol are available upon request from the first author. These questions were divided into six different categories in order to synthesize a number of factors belonging to different temporal dimensions in the family business research, in line with the suggestions by Sharma et al. (2014).

4.3. Data Analysis

To analyze the data we followed the pattern matching technique that compares the empirical data with the predicted behavior. The synthesis of the interviewees’ responses in a tabular form allowed us to find the presence of patterns aligned with the factors related to the three barriers: invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism (Brown and Eisenhardt 1997). Then, we contrasted these patterns with each one of the questions developed as the conceptual framework of this study. In fact, these questions include the dependent variables, namely, women’s desirability, acceptability by others, and their owned perception about having the capacity to become a leader in the family business. In this way, we obtained a close linkage between empirical evidence and the emergent theory that seek to explain the connection between the three perspectives with TPB (De Massis and Kotlar 2014; Gibbert et al. 2008; Langley and Abdallah 2011).

The next section analyses the factors that affect each woman’s desirability to lead the family business.

5. Discussion of Results

5.1. Women’s Desirability to Lead the Family Business

We discuss the findings obtained from the interviews to explain how factors listed in Figure 1 affect women’s incentive to lead the family business.

5.1.1. Remuneration

A salary should reflect the higher level of responsibility carried by the leader. However, the literature shows that in some settings, women are not paid at all for their effort (Gherardi 2015). This finding does not conform to our results, according to which all interviewees report to receive a formal economic compensation for their work. Interviewee 2 confirms: “I consider my salary fair given the activities I perform. In addition, I find the salary to be fair compared to what my (male) cousin gets, and that would be the case even if he will perform my role, as his salary would be the same as mine”.

5.1.2. Recognition

Beyond monetary incentives, women’s desire to lead the family enterprise is driven by gaining recognition from other family members and employees. Specifically, all respondents perceive their work performance to be highly appreciated and broadly recognized by their family members. In fact, one of the respondents (Interviewee 2) admits, “…the CEO (her mother) takes into account my opinions and my decisions count with her support”. This observation is further supported by Interviewee 8, who states: “(my…) opinions in business matters are invaluable and are taken into account for all kinds of decisions in the company”. Both findings stand in a stark contrast with a large volume of studies documenting the lack of recognition of women’s effort at work (e.g., Francis 1999).

5.1.3. Childcare and Flexible Working Hours

In order to facilitate women’s progression in their professional careers, businesses offer the option of flexible schedules and other intangible benefits. However, this initiative is pursued only by two enterprises in our sample. This is important since with the exception of one interviewee (Interviewee 4), all women have or had a family of their own. In the two cases, women have flexible working arrangements, which help them combine childcare with professional responsibilities. As Interviewee 7 admits “In general, my schedule depends on the number of events and tasks to be completed, but it is flexible given my family responsibility”. However, other interviewees’ working hours are not only fixed, but in three cases, they exceed the standard hours and stretch over to the weekend. Interviewee 4 provides the evidence of the latter stating: “I work an extra 3 h per week, although I am trying to reduce this time by prioritizing my personal life”. Thus, the majority of women in our sample have faced a difficult trade-off between their labor and leisure time, often working the ‘second shift’ at home (Hochschild and Machung 2012).

5.2. Others’ Acceptance of a Female Leader

For the successful leadership of women in the family business, the approval of family members and employees is as important as their personal and professional aspirations. The following section verifies how social norms affect such an approval.

5.2.1. Education and Experience

The acceptance of a new business leader is often conditional on the candidate’s merits, including her education and experience. All women in our sample have a higher education degree, with most of the degrees in a business-related field of study. Additionally, three respondents have postgraduate-level qualifications. According to Aronoff (1998), woman’s level of education is a strong predictor of her chances for obtaining leadership positions at work. Consistent with this finding, the women in our sample should expect better career prospects than women without the equivalent qualifications. Indeed, as Interviewee 1 states: “I consider that my position is fair with the preparation because I know the company quite well, I am very committed to it, and I have the knowledge that I acquired in my studies (Business Administration degree). Besides, I always enroll in activities that improve my knowledge of the company’s operations, and now I realized that there are still many areas, which I could improve. Hence, if I have the full ability to achieve these goals, I will make the company grow”.

In addition to education, experience is considered a crucial factor in the assessment of women’s suitability for key managerial positions (e.g., Hisrich and Fülöp 1997). Interestingly, the women in our sample report that the positions they hold in the family business correspond to their level of preparation and education, thus viewing their treatment as fair and unbiased. More importantly, all participants of the study have had previous work experience, which mostly consisted of supervising and leading other employees. The duration of their supervisory experience varies from 3 to 23 years, while the number of supervised employees ranges from 4 to 42.

In addition to supervising roles, three interviewees have worked in different positions in the family business prior to their progression to a leadership role. For instance, Interviewee 4 explains that during her preparation of a professional thesis five years prior to the interview, she began to do some administrative work to help her mother. After finishing the thesis, she started to look for a job, but upon not receiving any offers she found herself more and more involved in the administrative work in the family business. She states; “…then I helped my mother (…a general manager) to process a machinery import and to open an aluminium exhibition room. While daily attending this place, visitors started to ask me for advice about home aluminium installation. So, I was involved in initiating this new business segment. It took 14 months to gain my mother’s trust to be left in charge of this new area and to formally enter the enterprise”. It follows, therefore, that experience may benefit women’s progression to key managerial roles but this is conditional on the trust secured from the business owner.

5.2.2. Family Support (Male Siblings, Female Bosses and Succession)

While education and experience influence the acceptability of a female in the leader’s role, the chance for becoming a leader increases with the support provided by family members. The backing of the current business owner is of particular importance. Interviewee 4, who admits that in addition to her level of education and the informed perspective that she held about the business, she also received the support of her mother who, at that time, was leading the business, reiterates this importance.

Not only the support of the business owner matters for a female’s progression to the leadership level, but also the gender of the owner is relevant. As documented by Allen and Langowitz (2003), it is more viable for women to take over from the female business owners than the male ones. This is true in six cases in our sample, where there had been women involved in the family business, and in two of them, the mothers of the interviewees occupied the position of CEO. Succeeding a male owner might also be advantageous to a woman. For instance, a number of studies supports the claim that the father-daughter relationship is more harmonious and it is characterized by frequent communication (Smythe and Sardeshmukh 2013). Indeed, Interviewee 3 reports: “In the graphic arts and publicity we communicate daily between my dad and me, and with the other people who work with us at least once a month. Simply we have work meetings talking and proposing things for future projects”. In fact, in this case, the succession process is underway with this individual having been chosen over her younger brother, who decided to follow a career in the legal profession. Thus, our results indicate that the support from founders/owners and their recognition of the female’s efficacy is indispensable for the acceptance of a female successor in the family firm.

5.2.3. Industry Sector

In general, the women in our study are not constrained by the type of industry they chose to work in. Specifically, all interviewees work in areas usually dominated by males, such as operations, production, and construction. Interviewee 1 explains: “Most of the collaborators are men, and sometimes it is difficult for them to obey a woman’s orders. However, over time I have learned to deal with it and solve problems in the shortest possible time”. Thus, even male-dominated industry sectors do not pose obstacles for women in the leadership role.

5.3. Women’s Perception That Their Behavior Will Lead to the Desired Outcome

Beyond one’s own desire and family support, it is important that women believe that their actions will enable them to reach the leading position in the family business. We analyze this belief by investigating the leadership style that women employ and the presence of family conflict.

5.3.1. Leadership Style

The interviewees admit that by means of their managing style, they transmit family values to future generations. Interviewee 5 informs that one of these values is educating children to become independent. Interviewee 7 adds: “…we instil family and professional values through our own behavior; family values, such as harmony and above all humility, are transmitted to the company”. The other values most cited by the respondents entailed responsibility, resilience, and honesty. Moreover, women are aware of the importance of these values for the business, which is explained by Interviewee 2, who states, “…as we are two generations who jointly manage the family business, we are very aware of the sacrifice we have to make and the dreams we want to achieve since the business started”. Therefore, the women’s focus on upbringing their children reinforces the transformational style of leadership, which plays a crucial role in supporting the company’s long-term success, as argued by Arzubiaga et al. (2018).

The leadership style is also determined by the business vision of the company. In our sample, the majority of the interviewees aspire to introduce more changes benefitting the family business. One example is Interviewee 1 who states, “…the main change I would have done, is to have greater control of the construction projects and to keep working according to the chronogram. However, my boss (her father) suddenly overlooks the chronogram and makes unplanned decisions that lead to money and time losses”. Interviewee 4, who explains the need “to reassign employees to their right positions, to improve services, and to move toward a more proactive working climate”, makes a similar comment. However, this interviewee also admits: “that may cause some conflict with my parents, who always mention my lack of character and my permissive style of management”. These visions of improved business practice provide further evidence of women exerting the transformational leadership style.

On the other hand, female CEOs are said to employ the transactional management style instead of the transformational one, as this style is more useful in dealing effectively with everyday tasks (Gabrielsson et al. 2007). This is not necessarily the case in our study, where interviewees would have often participated in a conflict situation in the family company, usually with the intention of either stopping the aggravation or preventing it in the first place. They entail more instrumental roles, such as logistic planning, installation projects and, ISO 9000 certification, among others (Judge and Livingston 2008; Mueller and Dato-On 2008). Thus, the women in our sample employ certain elements of transformational and transactional leadership styles in their family businesses.

5.3.2. Family–Firm Conflict

As reiterated by Vera and Dean (2005), a conflict reduces the women’s chances to reach top positions in family firms. In the following, we analyze whether the family–firm conflict affects leadership aspirations of our interviewees.

Four interviewees admit the existence of the conflict, but try to reduce it by implementing various strategies, for example, by appropriate planning and organizing. For instance, Interviewee 6 states: “Yes, the daily work relationship often gets out of control and it cannot be separated from my personal life. My personal life is with my husband at home, so the relationship between home and the office constantly overlap. It is important to have a lot of patience, a lot of control, and above all tolerance”.

Nevertheless, such strategies are not always effective, and the conflict remains, as for Interviewees 1 and 8, where the interviewees regret that the business often takes priority over family life. In some cases, this actually has a detrimental effect on the business itself, as explained by Interviewee 1: “I feel that our situation as a family business has affected our performance, we have been absorbed by the daily work pace and we do not have the vision that would permit us to progress and develop the business”. Thus, in accordance with other findings in the literature, women find it difficult to reconcile family and business matters, which negatively affects their ability to take up leadership roles (Dumas 1989).

6. Conclusions

The first belief we considered was the women’s desire to lead the family business, which was influenced by remuneration, recognition, and flexible working arrangements. Our results indicate that the women received a fair salary, and their effort was recognized and acknowledged. These results provide no support of invisibility, widely documented in terms of remuneration and recognition received by women working for the family enterprises.

The results concerning remuneration and recognition do not extend to flexible working hours, where the women reported more demands imposed on them because of their leading role in the family business. This finding does not support numerous observations, according to which the women working for their family firms benefit from additional security, flexibility and support. There are two possible explanations for why this is occurring. First, the lack of recognition of the childcare obligations may indicate the women’s invisibility suggesting that this barrier remains an impediment to the women’s leadership. Second, this outcome might be associated with the idea of ‘second shift’ introduced by Hochschild and Machung (2012) exposing the dual career-household issues induced through sexism.

We evaluated how the acceptability was influenced by the women’s education and their working experience, support of family members, as well as the industry sector in which the women work. The interviewees also admitted that support of the family and particularly their parents-usually the current owners—played an important role in making the decision to lead the business. More importantly, the interviewees received support from both female and male owners.

Furthermore, the glass ceiling effect and gender role orientation are undermined by the fact that the majority of our interviewees are successfully working in male-dominated industry sectors. Our results also emphasize a high frequency of communication that the women held with the business owner as well as other team members, and these agents’ recognition of the women’s self-efficacy.

To complete the beliefs that generate women’s intention to lead a family firm, we must also account for these women’s perception of their own capacity to lead. The factors that we analyzed in this context were the women’s leadership style and family–firm conflict. Moreover, multi-tasking demonstrated by taking on different roles in the business, while simultaneously combining it with family life proves that women possess the competencies that are crucial for the success of the business (Mitchelmore et al. 2014).

Our results also show that the women struggle to combine their family and business duties, although they apply various strategies to reduce the impact of this conflict on their leadership. This confirms that the women’s performance in the leadership roles is dependent on their personal circumstances. This observation provides further evidence of sexism being persistent in terms of a female leading family firms.

Overall, our results support only a small proportion of the existing findings on female leadership in family businesses, implying that the barriers of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism have less impact than what has been documented elsewhere. Nonetheless, we believe that our study provides a modest attempt at subsuming and aligning different findings on the leadership role of women, particularly in terms of a family business. More specifically, we show that the barriers of invisibility, the glass ceiling effect and sexism can relate to different theoretical perspectives in different ways. In this study, we propose their alignment with TPB. We find that the invisibility elements affect to a larger extent women‘s desirability to lead a family business, glass ceiling factors affect mostly their recognition by others (family and non-family members), while sexism plays a crucial role in shaping their perception of being a successful leader. Therefore, this study may serve to open new promising avenues for research on female family members ascending to leadership positions and being successors in their family businesses, with important theoretical and practical implications.

Finally, we are aware that due to the size of our sample, our results might not be generalizable. We also acknowledge that certain socio-economic and cultural aspects may limit the transferability of our results to countries and cultural settings that differ from Mexico. Thus, future research could address these limitations by investigating barriers to leadership in other geographical, cultural, social, economic, political or geographical contexts to either confirm or refute the robustness of our finding. It would also be interesting to see whether the present results can be replicated in a larger sample size in Mexico and in other geographical locations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.D.-E., A.P.-C. and K.W.-M.; Formal analysis, J.D.-E., K.W.-M. and A.P.-C.; Methodology, J.D.-E., K.W.-M. and A.P.-C.; Visualization, A.P.-C.; Writing—original draft, J.D.-E.; Writing—review & editing, K.W.-M., J.D.-E. and A.P.-C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Note

| 1 | Directorio Estadístico Nacional de Unidades Económicas (DENUE), part of the National Institute of Statistics and Geography (Spanish: Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, INEGI). |

References

- Ajzen, Icek. 1985. From Intentions to Actions: A Theory of Planned Behaviour. Action Control, 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek. 1991. The theory of planned behaviour. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes 50: 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, Icek, and Martin Fishbein. 1980. Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behaviour. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, Ellaine I., and Nan S. Langowitz. 2003. Women in Family-Owned Businesses. Boston: MassMutual Financial Group and Center for Women’s Leadership at Babson College. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, Craig. E. 1998. Megatrends in family business. Family Business Review 11: 181–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzubiaga, Unai, Txomin Iturralde, Amaia Maseda, and Josip Kotlar. 2018. Entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in family SMEs: The moderating effects of family, women, and strategic involvement in the board of directors. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 14: 217–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Louis B., and Colleen Kaftan. 1990. Organizational Transitions for Individuals, Families and Work Groups. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Barrett, Mary, and Ken Moores. 2009. Spotlights and shadows: Preliminary findings about the experiences of women in family business leadership roles. Journal of Management & Organization 15: 363–77. [Google Scholar]

- Benokraitis, Nijole Vaicaitis. 1997. Subtle Sexism. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bitektine, Alex. 2008. Prospective case design: Qualitative method for deductive theory testing. Organizational Research Methods 11: 160–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Borkowski, Mark. 2001. Options for Buying and Selling a Family Business. Canadian Plastics 59: 26–28. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, Shona L., and Kathleen M. Eisenhardt. 1997. The art of continuous change: Linking complexity theory and time-paced evolution in relentlessly shifting organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly 42: 1–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Cadieux, Louise, Jean Lorrai, and Pierre Hugron. 2002. Succession in women-owned family businesses: A case study. Family Business Review 15: 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campopiano, Giovanna, Alfredo De Massis, Francesca Romana Rinaldi, and Salvatore Sciascia. 2017. Women’s involvement in family firms: Progress and challenges for future research. Journal of Family Business Strategy 8: 200–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carraher, Shawn M. 2005. An Examination of Entrepreneurial Orientation: A Validation Study in 68 Countries in Africa, Asia, Europe, and North America. International Journal of Family Business 2: 95–100. [Google Scholar]

- Cesaroni, Francesca Maria, and Annalisa Sentuti. 2014. Women and family businesses. When women are left only minor roles. The History of the Family 19: 358–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, Sea-Jin, Arjen van Witteloostuijn, and Lorraine Eden. 2010. From the Editors: Common method variance in international business research. Journal of International Business Studies 41: 178–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, Jess H., James J. Chrisman, and Paramodita Sharma. 1999. Defining the Family Business by Behaviour. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 23: 19–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cole, Patricia M. 1993. Women in Family Business: A Systemic Approach to Inquiry. Ph.D. dissertation, Nova Southeastern, University, Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Patricia M. 1997. Women in family business. Family Business Review 10: 353–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cromie, Stanley, and Sarah O’Sullivan. 1999. Women as managers in family firms. Women in Management Review 14: 76–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curimbaba, Florence. 2002. The dynamics of women’s roles as family business managers. Family Business Review 15: 239–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Massis, Alfredo, and Josip Kotlar. 2014. The case study method in family business research: Guidelines for qualitative scholarship. Journal of Family Business Strategy 5: 15–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dugan, Ann M., Sharon P. Krone, Kelly LeCouvie, Jennifer M. Pendergast, Denise H. Kenyon-Rouvinez, and Amy M. Schuman. 2008. A Woman’s Place: The Crucial Roles of Women in Family Business. Marietta: Family Business Consulting Group. [Google Scholar]

- Dumas, Colette. 1989. Understanding of father–Daughter and father–Son dyads in family-owned businesses. Family Business Review 2: 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Colette. 1990. Preparing the new CEO: Managing the father–daughter succession process in family businesses. Family Business Review 3: 169–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Colette. 1992. Integrating the daughter into family business management. Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice 16: 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dumas, Colette. 1998. Women’s pathways to participation and leadership in the family-owned firm. Family Business Review 11: 219–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M. 1989. Building Theories from Case Study Research. Academy of Management Review 14: 532–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenhardt, Kathleen M., and Melissa E. Graebner. 2007. Theory Building from Cases: Opportunities and Challenges. Academy of Management Journal 50: 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, Anne E. 1999. The Daughter also Rises: How Women Overcome Obstacles and Advance in The Family-Owned Business. San Francisco: Rudi. [Google Scholar]

- Frishkoff, Patricia A., and Bonnie M. Brown. 1993. Women on the move in family business. Business Horizons 36: 66–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabrielsson, Jonas, Morten Huse, and Alessandro Minichilli. 2007. Understanding the leadership role of the board Chairperson through a team production approach. International Journal of Leadership Studies 3: 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Galiano, Alanna M., and John B. Vinturella. 1995. Implications of gender bias in the family business. Family Business Review 8: 177–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, Silvia. 2015. Authoring the female entrepreneur while talking the discourse of work-family life balance. International Small Business Journal 33: 649–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gherardi, Silvia, and Manuela Perrotta. 2016. Daughters taking over the family business: Their justification work within a dual regime of engagement. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 8: 28–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbert, Michael, Winfried Ruigrok, and Barbara Wicki. 2008. What passes as a rigorous case study? Strategic Management Journal 29: 1465–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillis-Donovan, Joanne, and Carolyn Moynihan-Bradt. 1990. The power of invisible women in the family business. Family Business Review 3: 153–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffee, Robert, and Richard Scase. 2015. Women in Charge (Routledge Revivals): The Experiences of Female Entrepreneurs. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg, Steven D., and Bill Wooldridge. 1993. Self-confidence and managerial autonomy: Successor characteristics critical to succession in family firms. Family Business Review 6: 55–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Xuguang, and Jon M. Werner. 2016. Gender, family and business: An empirical study of incorporated self-employed individuals in the US. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 8: 373–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberman, Heather, and Sharon M. Danes. 2007. Father–daughter and father–son family business management transfer comparison: Family FIRO model application. Family Business Review 20: 163–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haynes, Deborah C., Rosemary J. Avery, and Holly J. Hunts. 1999. The decision to outsource child care in households engaged in a family business. Family Business Review 12: 269–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hisrich, Robert D., and Gyala Fülöp. 1997. Women entrepreneurs in family business: The Hungarian case. Family Business Review 10: 281–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell, and Anne Machung. 2012. The Second Shift: Working Families and the Revolution at Home. London: Penguin Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hollander, Barbara S., and Wendi R. Bukowitz. 1990. Women, family culture and family business. Family Business Review 3: 139–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, Margaret M. C. 2013. Daughter succession: A predominance of human issues. Journal of Family Business Management 3: 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iannarelli, Cynthia L. 1992. The Socialization of Leaders in Family Business: An Exploratory Study of Gender. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, USA. Unpublished. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, Timothy A., and Beth A. Livingston. 2008. Is the gap more than gender? A longitudinal analysis of gender, gender role orientation, and earnings. Journal of Applied Social Psychology 93: 994–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Keating, Norah C., and Heather M. Little. 1997. Choosing the successor in New Zealand family farms. Family Business Review 10: 157–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kram, Kathy E., and Marion McCollom Hampton. 1998. When women lead: The visibility-vulnerability spiral. In The Psychodynamics of Leadership. Edited by Edward B. Klein, Faith G. Gabelnick and Peter Herr. Madison: Psychosocial Press. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, Ann, and Chahrazad Abdallah. 2011. Templates and turns in qualitative studies of strategy and management. Research Methodology in Strategy and Management 6: 201–35. [Google Scholar]

- Lyman, Amy R., Matilde Salganicoff, and Barbara Hollander. 1985. Women in family business: An untapped resource. SAM Advanced Management Journal 50: 46–49. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Jiménez, Rocio. 2009. Research on Women in Family Firms: Current Status and Future Directions. Family Business Review 22: 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchelmore, Siwan, Jennife Rowley, and Edward Shiu. 2014. Competencies associated with growth of women-led SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 21: 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, Stephen L., and Mary Conway Dato-On. 2008. Gender-role orientation as a Determinant of entrepreneurial self-efficacy. Journal of Development Entrepreneurship 13: 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nekhili, Mehdi, Hela Chakroun, and Tawhid Chtioui. 2018. Women’s leadership and firm performance: Family versus nonfamily firms. Journal of Business Ethics 153: 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelson, Teresa, and Christina Constantinidis. 2017. Sex and Gender in Family Business Succession Research: A Review and Forward Agenda from a Social Construction Perspective. Family Business Review 30: 219–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Valerie, Angela Hamouda, Helen McKeon, Colette Henry, and Kate Johnston. 2006. Co-entrepreunerial ventures. A study of mixed gender founders of ICT companies in Ireland. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 13: 600–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeke, Kathyann Kessler, Diana Bilimoria, and Sheri Perelli. 2013. The dearth of daughter successors in family businesses: Gendered norms, blindness to possibility, and invisibility. Journal of Family Business Strategy 4: 201–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Overbeke, Kathyan Kessler, Diana Bilimoria, and Toni Somers. 2015. Shared vision between fathers and daughters in family businesses: The determining factor that transforms daughters into successors. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Poza, Ernesto J., and Tracey Messer. 2001. Spousal leadership and continuity in the family firm. Family Business Review 14: 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, Michael G. 2009. For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal 52: 856–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reay, Trish. 2014. Publishing qualitative research. Family Business Review 27: 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roffey, Bet, Anthony Stanger, David Forsaith, Elspeth McInnes, Franca Petrone, Chris Symes, and Maria Xydias. 1996. Women in Small Business: A Review of Research. Canberra: Australian Government Publishing Service. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, Barbara R., and Gong-Soog Hong. 2000. The role of wives in family businesses: The paid and unpaid work of women. Family Business Review 13: 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salganicoff, Matilde. 1990. Women in family businesses: Challenges and opportunities. Family Business Review 3: 125–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, Pramodita, Carlo Salvato, and Trish Reay. 2014. Temporal dimensions of family enterprise research. Family Business Review 27: 10–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smythe, Jessica, and Shruti R. Sardeshmukh. 2013. Fathers and daughters in family business. Small Enterprise Research 20: 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonfield, Matthew C., and Robert N. Lussier. 2012. Gender in family business management: A multinational analysis. Journal of Family Business Management 2: 110–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Songini, Lucrezia, and Paola Dubini. 2003. ‘Glass ceiling in SMEs: When women are in command’. Paper presented at the Annual Academy of Management Meeting, Seattle, WA, USA, July 30–August 3. [Google Scholar]

- Songini, Lucrezia, and Luca Gnan. 2014. The glass ceiling in SMEs and its impact on firm managerialisation: A comparison between family and non-family SMEs. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics 9: 170–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, Janet T., and Camille Buckner. 2000. Instrumental and expressive traits, trait stereotypes, and sexist attitudes. Psychology of Women Quarterly 24: 44–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- St-Arnaud, Louise, and Emilie Giguère. 2018. Women entrepreneurs, individual and collective work–family interface strategies and emancipation. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 10: 198–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swim, Janet, and Laurie Cohen. 1997. Overt, covert, and subtle sexism: A comparison between the attitudes toward women and modern sexism scales. Psychology of Women Quarterly 21: 103–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Economist. 2004. Business in Mexico: Still Keeping It in the Family. Available online: https://www.economist.com/business/2004/03/18/still-keeping-it-in-the-family (accessed on 15 June 2021).

- Trevinyo-Rodríguez, Rosa Nelly. 2009. From a Family-Owned to a Family-Controlled Business. Journal of Management History 15: 284–98. [Google Scholar]

- Trevinyo-Rodríguez, Rosa Nelly. 2010. Empresa Familiar: Visión Latinoamericana. Ciudad de México: Pearson Education. [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo, Manuel Carlos. 2008. Is the culture of family firms really different? A value-based model for its survival through generations. Journal of Business Ethics 81: 261–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, Manuel Carlos. 2009. Analytical model of leadership in family firms under transformational theoretical approach: An exploratory study. Family Business Review 22: 136–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veale, Camilla, and Jeff Gold. 1998. Smashing into the glass ceiling for women managers. Journal of Management Development 17: 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vera, Carolina F., and Michelle A. Dean. 2005. An examination of the challenges daughters face in family business succession. Family Business Review 18: 321–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Robert. 1994. Case Study Research, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).