Abstract

The importance of kin relationships varies with socioecological demands. Among subsistence agriculturalists, people commonly manage fluctuations in food availability by relying on family members to share resources and pool labor. However, the process of market integration may disrupt these support networks, which may begin to carry costs or liabilities in novel market environments. The current study aims to address (1) how kin are distributed in household support networks (2) how kin support varies as households become more engaged in market activities, and (3) how variation in kin support is associated with income disparities within a Yucatec Maya community undergoing rapid market integration. Using long-term census data combined with social networks and detailed household economic data, we find that household support networks are primarily composed of related households. Second, households engaged predominantly in wage labor rely less on kin support than agricultural or mixed economy households. Finally, kin support is associated with lower household net income and income per capita. Understanding how kin support systems shift over the course of market integration and in the face of new opportunities for social and economic production provides a unique window into the social and economic drivers of human family formation.

1. Introduction

Behavioral ecology approaches to the study of the human family often focus on how the costs and benefits of kin support are shaped by the demands of subsistence and economic production. A fundamental approach to Human Behavioral Ecology (HBE) starts with a question of how social and ecological conditions determine the costs and benefits of different behavioral alternatives. Recent reviews of contemporary HBE work have identified a clear focus on resource sharing and differences in kin vs. non-kin interactions (Nettle et al. 2013). HBE studies of the family have recently used network approaches to understand how kin relationships are structured and maintained over the life course and their role in shaping divisions of labor and reproduction (Scelza and Bird 2008), the diversity and variation of kin and non-kin cooperation (Kasper and Mulder 2015; Hooper et al. 2013) and intergenerational transfers of resources (Hooper et al. 2015).

While many key features of human social structure are consistent across culture and ecology (Hamilton et al. 2007; Hill and Dunbar 2003), economic development appears to stimulate flux in the composition and structure of social networks. Populations recently exposed to market integration are argued to have less dense kin-networks, and more frequent interactions with unrelated strangers (Newson and Richerson 2009; Colleran 2020). Many prominent theories of economic development posit that changes in social networks are a primary driver of the sweeping transformations that accompany modernization, particularly as market and government institutions take on functional roles once held by kin relationships (Notestein 1945; Handwerker 1986; Inkels and Smith 1974; Gurven et al. 2015). Scholars have argued that these shifts in social networks away from heavy reliance on kin shift fertility dynamics (Newson and Richerson 2009), social norms (Santos et al. 2017), prosocial behaviors (Henrich et al. 2005), and even the pace of economic development (Eagle et al. 2010). Additionally, network relationships are important determinants of health outcomes in both pre-industrial and post-industrial contexts (Smith and Christakis 2008; Kramer 2010).

The decline in kin in social support networks has significant implications for how resources flow between individuals and families in populations. Traditional sharing and exchange networks including both kin and non-kin are strategies to minimize the risks associated with subsistence production (Dyble et al. 2016; Kaplan et al. 2012; Kramer 2018). However, exposure to markets and wage labor presents new options to manage risk besides reliance on social support networks. Cash, formal financial institutions, credit, and government subsidies and programs provide alternative means to access, store, and build resources. However, availability, efficiency, and familiarity with these new alternatives may limit how easily they replace informal kin and non-kin support relationships. Indeed, both HBE and economic explanations of how market integration alter social networks often emphasize either the costs of maintaining dense traditional networks composed primarily of kin (di Falco and Bulte 2011; Jaeggi et al. 2016; Gurven et al. 2015) or the social, economic, and informational benefits to adopting wider, more diverse relationships with a greater proportion of non-kin (Lin 2017; Burt 2017; Granovetter 1973; Derex and Boyd 2016).

Here, we aim to address (1) how kin are distributed in household support networks in a community undergoing rapid economic development and market integration, (2) how the role of kin in support networks vary as households become more engaged in market activities, and (3) how variation in kin support networks are associated with increasing wealth disparities within a Yucatec Maya community undergoing rapid market integration.

2. Background

2.1. Socioecological Changes Associated with Market Integration

Market integration is associated with a host of socioecological changes that have long been studied in the social sciences. Market integration studies (often also referred to as modernization and industrialization) have identified cascading effects of market involvements on subsistence and indigenous communities (Godoy 2001), health and well-being outcomes (Godoy et al. 2005a; Urlacher et al. 2016), changes in ecological knowledge (Godoy et al. 2005b, 2016), and increasing prosocial behaviors (Gurven et al. 2015; Henrich et al. 2005).

Primarily, market integration is associated with a key shift in household production, as new economic opportunities emerge alongside traditional subsistence practices. In these contexts, households face trade-offs in pursuing new social and economic opportunities, or maintaining traditional economic production. Mixed economies arise when households and communities are engaged in both the cash economy and subsistence production and maintain traditional sharing and cooperative relationships (Burnsilver and Magdanz 2019; Ready and Power 2018) as well as pursue new institutional and social relationships. This context creates unique trade-offs that households must navigate as they balance traditional economic and social behaviors with novel and often uncertain market opportunities (Kramer et al. 2021).

In communities where market opportunities are centered on cash cropping, a commitment to wage labor reflects a striking divergence from traditional household economics. Indeed, anthropologists have argued that the commitment to competitive wage-labor jobs is precisely what drives the cascading suite of changes associated with market integration (Handwerker 1986; Shenk 2005). The reliance on cash and cultivating new skill sets give rise to new time allocation and parental investment trade-offs, promoting a dramatic shift in household behavior (Colleran et al. 2015). Additionally, as networks expand and become composed of ties to diverse types of groups and individuals, households benefit in competitive wage-labor contexts by increasing exposure to novel information and contacts that can be leveraged into employment opportunities (Granovetter 1983; Burt 2017). Households with these types of outward looking networks may be more inclined to enter wage-labor employment and forgo traditional economic production. However, for households that double down on agricultural production as the means to generate cash and participate in the market economy, local and kin-based sharing networks may better serve to offset fluctuations in agricultural returns.

2.2. Costs and Benefits of Kin Support Networks in Mixed Economies

Support networks have well-documented effects on individual and household economic wellbeing (Szreter and Woolcock 2004; Poortinga 2006), particularly in subsistence economies where kin support is often associated with benefits for fertility, food security, and health outcomes (Gibson and Mace 2005; Hadley et al. 2007; Harder and Wenzel 2012; Hadley 2004). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence that kin support networks provide benefits in mixed economies (Burnsilver et al. 2016; Ready and Power 2018; Eakin 2005). However, the effects of kin support on economic outcomes may be strongly conditioned by the types of economic production a household engages in. For example, for households committed primarily to agricultural production, dense, homogenous, and kin-based networks may prove beneficial by reinforcing norms of sharing, reciprocity, and resource pooling (Portes 1998). Alternatively, households with few kin support ties, or more diffuse networks may struggle to mobilize labor and resources needed for peak times of agricultural production.

By contrast, these same network structures can become a liability when households branch out from agricultural production. For example, dense, kin-based networks may be a disadvantage in wage-labor households because of the costs imposed by obligations (K. Hoff and Sen 2006; di Falco and Bulte 2011). Economists have suggested kin systems play a role in poverty trap dynamics, where strong kin-based networks limit the incentives or opportunities for moving into the market sector. The mechanisms of informal mutual assistance that characterizes kin support networks can increase the costs to individuals and households moving into the wage-labor economy through increased demands by less successful kin members. These demands include monetary support, finding jobs, housing arrangements, transportation, and other time commitments that limit the ability to concentrate resources necessary for upward social mobility.

Additionally, kin dense networks can limit access to novel information about wage labor or market opportunities. More diffuse, heterogenous networks have been shown to provide advantages in wage-labor contexts through accessing and controlling the spread of novel information between disconnected clusters in the group (Newson and Richerson 2009; Burt 2017). Wage-labor households may benefit from cultivating unrelated, diverse and diffuse networks that foster novel information flow from diverse connections, or may help households realize returns to investments in education by accessing better-paying employment opportunities (Granovetter 1983; Matthews et al. 2009; Coleman 1988). Thus, the effects of kin support networks may hinge upon the economic activities of a household.

2.3. The Current Study

Here, we aim to address how kin support varies across households pursuing different economic strategies in a community undergoing rapid market integration. The Maya study population is located in a remote area of the Puuc region in the interior of the Yucatan Peninsula, Campeche, Mexico. The indigenous Yucatec Maya who inhabit this rural area live in small villages of subsistence maize farmers and in a few market and administrative towns. While not isolated, these Maya live in a dispersed and underpopulated region that is ethnically, socially and economically homogeneous.

In the early 1990s, all residents (n = 55 households, 316 individuals) made a living as small-scale agriculturists, the household was the unit of production, and each family grew and hunted for its food. As in many subsistence agricultural societies, high fertility is associated with large families that pool labor (Lee and Kramer 2002; Kramer 2005). Residents (n = 55 households, 316 individuals) lived primarily in households composed of nuclear families (82%). Other households included widowed or elderly parents or unmarried siblings. Without access to roads, vehicles, or mechanical farming equipment, there was little incentive to grow surplus crops or means to sell them at regional markets.

In this context of nuclear and multigenerational families, the household was the unit of production across which resources were pooled (Kramer 2002; Kramer 2005). These cooperative groups are readily identified by the Maya and are described as those who live, eat and work together. The composition of these households fluctuates with time, as children are born, mature and marry, and have children of their own (Lee and Kramer 2002). When young people marry, they often live temporarily with the husband’s natal family as they work to clear sufficient land and accumulate resources to build their own house. Establishing an independent household may take up to 10 years. In some cases, husbands relocate to their wives’ natal households. The majority of marriages are exogamous, occurring between community members, with ~10% of men and women marrying outside of the community.

Pooling resources and labor at the household level was essential for family survival. Older children contributed substantially to domestic and agricultural labor, as well as subsidizing the childcare costs of younger siblings (Kramer 2005; Kramer 2002, 2011). This traditional household organization, and the relationship between family size, labor and wealth, generate a context where labor allocation and economic production are seen as the result of household-level decision-making processes, rather than individual ones (Jessoe et al. 2018).

Rapid economic development began in the early 2000s when a paved road was built that facilitated access to new farming methods, the transportation of crops to market, children to schools and people to wage labor jobs. These changes expanded the ways in which households make their living. New subsistence options include mechanized farming, craft production, cash cropping, cultivating nut and seed crops for sale, and wage labor. Cash is now critical to pay for seed, fertilizer, pesticides and vehicles to transport crops to market, school fees, and to access market goods, and can be generated either through crop sales or wage labor. Many young adults work in unskilled part-time agricultural labor in neighboring communities or in a maquiladora several hours away. A few individuals work skilled jobs in larger towns, returning nightly or weekly. The community is transitioning from being unstratified to some families having a priority interest in access to land and other resources. The community is also undergoing changes in family formation, with both a decline in fertility and family size over the last 30 years, alongside an increase in uptake of tubal ligations at younger ages and lower parities (Kramer et al. 2021).

In sum, changes to farming practices, systems of land tenure, access to technology, cash, and wage labor have led to increasing economic and social variation. Additionally, the decline in fertility is shifting the demographic profile of the community. This growing diversity makes this an ideal case study to test how new economic opportunities shape kin-based support networks. We address three primary research questions. First, how are kin distributed in household support networks? Second, how does the role of kin in support networks vary as households become more engaged in market activities? And third, how does variation in kin support networks impact increasing wealth disparities within this community undergoing rapid market integration?

3. Methods

Data were collected from 97% of community households (n = 90) in 2017 using structured and semi-structured questionnaires regarding household composition, support networks, income and assets, and the primary economic activity of all members of the household. With the exception of individual-level relatedness and economic activities, data collection focused on the household level in order to capture whole networks and household economic status. Additionally, resource pooling occurs within the household, so economic variables such as income and material assets, such as vehicles, farm equipment, and consumer goods were collected at the household level.

3.1. Economic and Network Variables

Relatedness between households. Using census and reproductive history data collected in the community since 1992 we calculate the relatedness between all known individuals who have ever lived in the community (N = 710) using the kinship2 package in R (Sinnwell et al. 2014). The coefficient of r is used to express genetic relatedness between two individuals as a measure of the probability that the two individuals share the same allele variants. It is used to describe the degree of kinship between individuals, estimating the total proportion of genetic material shared through common ancestry. The average relatedness of all individuals included in the total census data was coef.r = 0.033. Considering the cross-sectional sample of individuals living in the community in 2017 (N = 544), average relatedness was coef.r = 0.036. The average level of kin depth, or generations per individual pedigree was 2.9 (sd = 1.5) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Household-Level Variable Descriptives—Means (Std. Dev).

Individual-level relatedness was then aggregated at the household level. Max relatedness between household is the maximum relatedness of any individual in household A to any individual in household B. Aggregating relatedness between households to the maximum relatedness of a given dyad in each household collapses nuanced distinctions that could be made within the data, primarily between patrilineal, matrilineal, and affinal kin. While these distinctions are undoubtedly important in many contexts (Lowes et al. 2020; Power and Ready 2019), these relationships may not be clearly distinguished at the household level. For example, if the female head of household identifies her brother in another household as a helper, for her it is a strong genetic tie, but for her husband the tie between households is affinal. We believe maximum relatedness provided the most parsimonious approach to testing our key hypothesis.

Household support networks. All male and female heads of household were asked network elicitation questions regarding support received and support given to the household, including targeted questions about whom the household would (1) borrow money (2) borrow items from, (3) ask for help in men’s work, and (4) ask for help in women’s work (Table S1 and Figure S1 for distributions). As questions were asked of household heads, in some rare cases, heads of household nominated another within the household (N = 93, ~16%). These within-household support ties were removed.

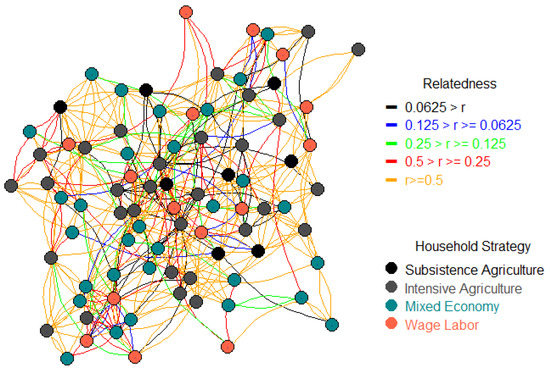

All support network questions were aggregated into a binary variable indicating if any member of one household nominated any member of another household, referred to here as support ties. This created a binary support network with all participating households within the community with a total of 437 support ties (Figure 1). From this household support network, summary measures were calculated to assess the overall support as well as the kin composition of the support networks. Total support ties are calculated as the degree of support ties, or the total number of households listed as giving any type of support to the ego household.

Figure 1.

Household support networks showing the relatedness coefficient between households (lines), and household economic strategy (nodes).

Total close kin support ties are calculated as the total number of support ties that are composed of households that share a strong genetic kin relation (coef of r ≥ 0.25). Proportion of support ties composed of kin is calculated as the proportion of the total support ties composed of households with a strong genetic relationship.

Household economic activities. Information collected in 2017 about how individuals spend their time revealed an expanding number of different types of economic activities, including agricultural production for subsistence or market, domestic work, craft industries, entrepreneurial activities, unskilled field wage labor and skilled wage labor. To estimate a households’ level of market integration we focus on the economic activities of the adult members of the household. The primary economic activity of all adults was coded as a combination of agricultural worker, wage-laborer, domestic worker, piece-work, or student. Using this coding, alongside measures of household access to agricultural land, we developed a measure of market integration. A household’s Primary Economic Strategy was coded as (i) subsistence agriculture if the amount of land cultivated is less than 3.0 ha (the minimum maize needed to sustain an average household of 8–10 individuals for a year); (ii) intensified agriculture if more than 3.0 ha are under cultivation; (iii) wage labor if the head-of-household works full-time for a salary; (iv) mixed strategy if the household maintains an agricultural base, but one or several household members (but not the head of household) is a full-time wage laborer. We include a sensitivity analysis of alternative measures of economic strategy (Tables S3 and S4) using the proportion of the adults in the household engaged in wage labor and the proportion of adults classified as agricultural workers.

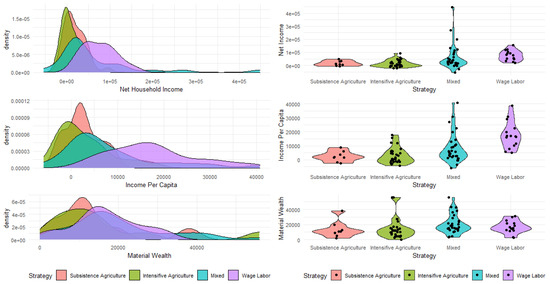

Household economic status. Household economic status was measured using income and asset values (Figure 2). Total net household income and material wealth. Total net household income was estimated using income from all sources, including wage labor, selling agricultural surplus, as well as including debts incurred from seed, pesticides, and non-agricultural expenses. For analyses, total net household income was centered and log-transformed. We also calculate income per capita, or the total net household income divided by the total number of adults age 15 or older in the household, to account for variation in household size. Lastly, material wealth is an asset-based measure of the total stocks of capital owned by a household. Material wealth was estimated using the sum of the total market value of all household assets, including furniture, household items, farm equipment, and vehicles. Three households were strong outliers in the value of their household assets (~10× the mean household asset wealth). For our primary analyses, we coded these as 60,000 p, or the next highest material wealth score in the distribution. Sensitivity analyses show no qualitative differences in the results of modeling material wealth (Table S5 and Figure S2).

Figure 2.

Distribution of household income and wealth variables by economic strategy.

3.2. Analyses

How kin are distributed in household support networks? To assess the amount of the total support network that is composed of kin, we first plot the frequency of different levels of between-household relatedness in the helping ties. We then employ a Social Relations Model (SRM) for binary outcomes using different levels of relatedness to predict the existence of a support tie between households. We further include a categorical variable for a household economic strategy to assess how the total number of support ties varies across households engaged in different types of economic activities.

The application of SRM models to network data in HBE has increased over the last decade, largely due to the interpretative advantages of decomposing directional node-level and relational-level effects, as well as accounting for both generalized and dyadic reciprocity (Koster and Leckie 2014; Koster et al. 2015). Node-level effects are the household characteristics, like household size and economic strategy, that capture variance in how often a household nominates others as helpers (Sender effects), and how often a household is nominated as a helper (Receiver effects). Relational effects are characteristics of dyads, such as the maximum relatedness between the two households, which capture variance in whether a tie exists between two households or not. Additionally, the SRM accounts for the correlations between giving and receiving, and within-dyad responses.

We fit the SRM using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) employing the amen package in R (Hoff 2018, 2015). Since the data are binary, we fit the model with a probit link function. We use a 1000-iteration burn-in with a distribution of 10,000 for the posterior parameter estimates. Model details and diagnostic plots are included in the supplemental materials (Figures S3–S5). We include three models in these analyses. First, we fit a model accounting for Relational effects, or the relatedness between households. We then include household characteristics as Sender effects, to assess how household economic strategy affects the household propensity for nominating helpers. Finally, we include household characteristics to assess both household likelihood of nominating helpers (Sender effects) and household propensity for being nominated as a helper (Receiver effects).

How does the number of kin in support networks vary as households become more engaged in market activities? To assess how the amount of kin in support networks varies as households engage in different economic strategies, we first compare the mean number of kin ties and the proportion of support ties composed of kin across different economic strategies. We use the non-parametric Kruskal–Wallis tests for global comparison, and the Dunn’s test with a Bonferroni alpha correction to account for multiple tests.

We then use regression analyses to assess if a household’s economic strategy predicts the total number of kin support and the proportion of helping ties composed of kin. For the total number of kin support ties, we use a Poisson regression model. However due to the under-dispersion of the count data (Figure S3), we use a Conway–Maxwell Poisson model, fit using the package COMPoisson in R (Sellers and Shmueli 2010). The Conway–Maxwell Poisson provides more accurate standard error estimates for under-dispersed Poisson count data (Shmueli et al. 2005).

To model the proportion of support ties composed of kin, we employ a zero-one-inflated beta model. While beta-regression models are commonly used for closed-interval, proportion data, one inflated model can account for the non-negligible amount of 1’s present in our data (Figure S3) (Ospina and Ferrari 2010, 2012).

For both models, we include the categorical variable indicating household economic strategy. Both models control for the total number of helping ties. Because kin nominations by a household may be constrained by the availability of kin, we include a variable for the total number of strong kin ties (r ≥ 0.25) in the community. To assess whether the effect of kin availability varies by economic strategy, we include an interaction term for economic strategy and the total number of kin ties in the community.

How variation in kin support networks are associated with increasing income disparities? To assess how kin support is associated with economic outcomes, we employ OLS regression with the total number of kin ties and proportion of kin in support networks predicting household income and asset-based wealth. We include household economic diversity and age of male head of household as control variables. To assess how the effects of kin support on income might vary across economic strategies, we test the interactions between household economic strategy and the total number of kin support ties and proportion of kin support ties in the regressions.

4. Results

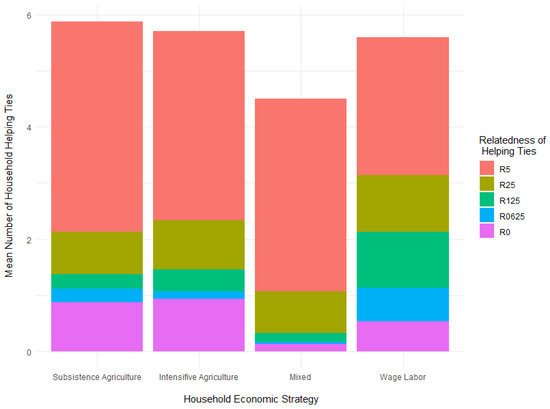

How kin are distributed in household support networks? Support ties between households are composed primarily of households with at least one strong genetic tie (Figure 3). On average, households nominated six other households for support, with nearly two-thirds (65%) of nominations composed of households with at least one strong genetic relationship (Coef. r ≥ 0.5). Additionally, regression estimates show strong relatedness significantly predicts a support tie between two households (Table 2).

Figure 3.

Kin composition of between household support ties.

Table 2.

Social Relations Model Results.

The SRM models highlight the importance of relatedness between households, represented by the dyadic effects. Relatedness at the level of r = 0.5 and r ≥ 0.25 positively predicts the existence of support ties in all models. Interestingly, low levels of relatedness between households, r ≥ 0.625 to r < 0.125, held a negative association with helping ties. That is, households with very low levels of relatedness were less likely to share a helping tie compared to households that were completely unrelated.

In the models that account for sender effects, the household economic strategy had significant effects on the existence of a helping tie. Compared to mixed-economy households, wage-labor and agricultural households had higher numbers of support ties, though the effects were only significant for wage-labor and intensive agricultural households (in the full models). Accounting for receiver effects showed that household economic strategy had no effect on the number of times a household was nominated as a helper. Additionally, household size had a negative sender effect, indicating that larger households were nominated fewer households than smaller households. However, household size had no significant receiver effects, indicating that larger households were not more likely to be nominated as helpers compared to smaller households.

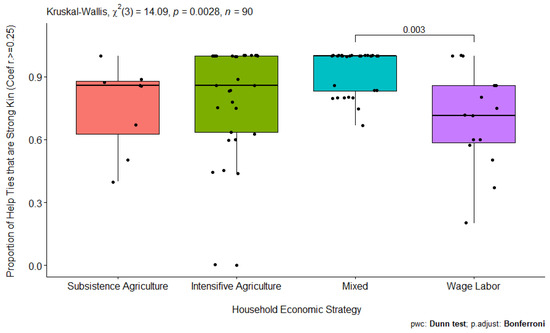

How does the number of kin in support networks vary as households become more engaged in market activities? Non-Parametric mean comparison tests show significant differences in the proportion of kin ties across economic strategy (Figure 4). Dunn’s pairwise tests show that mixed economy households have a significantly higher proportion of strongly related kin in support networks compared to wage-labor households (Figure 4, Table S2). While mixed economy households are less likely to have a support tie in general (Table 1 and Table 2), but of the ties that exist, they are primarily composed of strongly related households. When controlling for the total number of ties, mixed economy households have both significantly higher numbers of kin support ties compared to wage-labor households, and significantly larger proportions of support ties composed of kin compared to wage-labor households (Table 3). There were no significant differences between mixed economy households and both types of agricultural households. Perhaps unsurprisingly; for both models, the total number of helping ties and the total number of kin ties in the community had positive effects on the number of kin support ties a household reported and the proportion of helping ties composed of kin. In the one-inflated beta regression, the total number of helping ties and the total number of kin ties had an effect on the probability of listing all kin in the support network, while economic strategy held no significant effects.

Figure 4.

Proportion of support ties composed of kin stratified by household economic strategy.

Table 3.

Regression Models of Kin Support Ties.

Additionally, the interactions between the total number of kin ties in the community and household economic strategy were insignificant. This suggests that kin availability plays little role in the differences in kin support across households with different economic strategies. Furthermore, supplemental analyses show the proportion of household workers identified as agricultural workers is positively associated with total kin ties as well as the proportion of kin ties in support networks (Table S3).

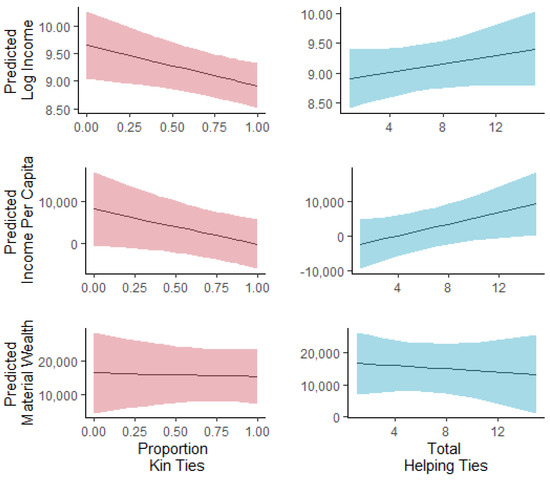

How variation in kin support networks are associated with increasing income disparities? The proportion of support ties composed of kin is associated with both lower log income and lower-income per capita (Table 4, Figure 5). Both mixed economy and wage labor households have higher overall incomes compared to agricultural households. However, neither proportion of kin ties nor household economic strategy was associated with increased asset-based wealth. The interaction between kin support and household economic strategy was not significant, indicating the negative association between kin support and income did not vary across the economic strategy. In our supplemental analyses, we find the proportion of adults identified as wage labor is positively associated with income measures, whereas the proportion of adults identified as agricultural workers was negatively associated with income measures. Finally, using these alternative measures of economic strategy, results still show a negative effect of the proportion of kin help on income measures (Table S4).

Table 4.

OLS Regression Models Predicting Household Economic Status.

Figure 5.

Marginal effects plots of Proportion of Kin Ties (Left) and Total Helping Ties (Right) on economic outcome variables. Marginal effects are calculated by holding constant all other variables in the model. Economic Diversity = 3.38, Age of Male HH = 44.15, Subsistence Agriculture = 1, Total Helping Ties = 5.41, and Proportion of Kin Help = 0.81.

5. Discussion

The results suggest that despite increasing market integration, between-household support networks are centered primarily around strong kin-based ties. However, we do find variation in kin support across different types of economic strategies. Mixed economy households tend to have fewer total supporting ties, yet their support networks are composed of significantly more kin relationships. By contrast, wage-labor households tend to have significantly fewer kin in their household support networks compared to mixed-economy households. This finding appears consistent with patterns observed in other populations undergoing market transitions, where increasing market integration is associated with lower kin density in networks (Colleran 2020). However, the greater reliance on kin support in mixed economy households is an interesting counterpoint to the narrative of a linear decline in kin density (Baggio et al. 2016; Burnsilver et al. 2017; Ready and Power 2018). As mixed economy households diversify economic production, taking up new wage-labor opportunities in addition to intensifying traditional economic production, reliance on kin support may remain a stable strategy for mitigating risk in the face of economic uncertainty (Baggio et al. 2016; Burnsilver et al. 2017; Ready and Power 2018).

Additionally, reliance on kin in household support networks is associated with lower overall income and income per capita for all economic strategies. The HBE framework suggests two potential explanations for this association, both emphasizing the costs and benefits of kin support (Gurven et al. 2015). One explanation is that better-off households are less likely to need kin support given their greater economic liquidity regardless of their economic strategy. Accordingly, households with more income benefit less from kin support, either because of the costs to accrue kin obligations or because reliance on cash is a better means to deal with fluctuations in resource flows. An alternative explanation is that kin support may be ultimately costly, whereby households who rely too heavily on kin may face the economic consequences of returning support for closely related households. The causal question still remains; do low-income households need kin support, or does kin support prevent the accumulation of more income? Our cross-sectional analyses are not suited to determine the direction of causation; however, we provide a baseline for future longitudinal analyses. Follow up-network studies could identify the role of network position in shaping future economic outcomes for households, including how and why households might adopt new activities.

Interestingly, our results highlight an important distinction in how household economic success is measured (Kaiser et al. 2017). Here we found significant effects of network composition on household income measures, but not material wealth measures. Income reflects the flow of resources through a household and in many low- and middle-income contexts may be highly variable. Material assets, or stocks of wealth, are much more stable temporally and can reflect the long-run economic capacity of a household. Our results suggest that network effects may have a short-term temporal impact on household economics. Rather than influencing a households’ stocks of wealth, one might argue that the effects of kin support networks on household economic status may play out on a short-term temporal scale, influencing the variable flows of resources a household has access to.

Our network approach emphasizes ties between households. A key limitation of this approach is that with market integration, individual and household economic interests may increasingly diverge. As new market opportunities arise, individuals may wish to diversify their networks beyond familial ties, in ways that may conflict with the interests of the household and thus are not captured in the aggregate household networks. While some research suggests household-level networks accurately approximate individual networks in subsistence populations (Koster 2018), an important question remains whether this holds true as household increasingly diversify their economic strategies. One might expect as households become more involved in the wage-labor economy; individual networks may increasingly diverge from household-level aggregates.

Another important limitation of our approach is how we measure relatedness between households. We chose to use the maximum relatedness between households as our key relational variable. However, households can be related in a number of different ways. Marriage ties between households may prove to provide an important means of extending kinship ties between households. Furthermore, relatedness through patrilines or matrilines may provide distinct or diverging advantages or disadvantages depending on the cultural contexts. However, one of the defining characteristics in human support networks is the flexible means by which kin are identified, and accessed through residence patterns, often in ways that maximize the number of support ties available to individuals and households (Power and Ready 2019; Hill et al. 2011; Kramer and Greaves 2011). One important question remains how different types of household relatedness ties may gain or lose prominence in support networks over the course of market integration.

These analyses offer a glimpse at how networks of kin support are changing in the contexts of increasing economic diversity in a population undergoing rapid economic development and market integration. Household commitment to solely wage labor appears to lessen the need for reliance on kin support, while economic diversification appears to increase the number of kin in support networks, though potentially decreasing the size of the overall support networks. Both economic strategies are novel in the community, as the opportunities for consistent wage-labor employment are relatively new. How and why a household might diversify economic production or intensify commitment to a single strategy, such as wage labor or agricultural production, is an important open question. Mixed economic strategies may serve as a safe means of entering the market economy, by maintaining traditional economic production and social support to combat the risk and uncertainty of precarious wage-labor positions (Eakin 2005).

Mixed economies are an opportunity to examine the wide range of social, economic, and demographic changes associated with market integration. The combination of traditional and novel, market-oriented economic opportunities means that social relationships may not only strengthen in importance for mitigating risks, but may also take on new functional significance. The importance of kin in support networks may also shift with changing demographics and reproductive dynamics. While fertility is declining in this community, and thus the future availability of both ascendant and collateral kin to recruit for support, households engaged in mixed economic strategies may benefit from balancing fertility with the need for enough productive adults to sufficiently diversify economic activities. The household’s capacity to both intensify agricultural production and engage in wage-labor opportunities may crucially depend on the availability of not just the support of related households but the reproductive decisions required to produce relatives.

6. Conclusions

HBE approaches to the family in contemporary populations have focused on the costs and benefits of kin support in diverse socioecological settings. In the contexts of market integration and economic development, HBE approaches have mirrored approaches in economics regarding the duel-edged sword of strong kinship networks. Here, we show that kinship ties strongly structure support networks despite market integration and economic development. Furthermore, a household’s economic strategy predicts the kin composition of support networks, with mixed-economy households relying more on kin than wage-labor households. Lastly, kin support is associated with lower overall incomes and income per capita, regardless of economic strategy. Taken together, kin support remains an important strategy to mitigate risk in this community, even in the face of greater opportunities for engagement in wage labor and with increasing economic inequality.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/socsci10060216/s1, Table S1: Distribution of Kin Ties in Household Support Networks, Table S2: Dunn’s Mean Comparison Tests of Average Proportion of Kin in Support Networks by Economic Strategy, Table S3: OLS Regression of Total Number of Kin Ties and Proportion of Kin Ties in Support Networks, Table S4: OLS Regression Predicting Household Economic Status, Table S5: Material wealth with uncoded outliers, Figure S1: Distribution of Kin in support networks by support type, Figure S2: Economic outcomes with un-recoded material wealth distributions, Figure S3: Distribution of proportion of kin help and total kin support ties, Figure S4: SRM Diagnostic Plots for Dyad only model, Figure S5: SRM Diagnostic plots for Dyad+Sender Effects, Figure S6: SRM Diagnostic plots for Dyad+Sender+Reciever Effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.L.K. and J.V.H.; methodology, K.L.K.; formal analysis J.V.H.; investigation, K.L.K.; data curation, K.L.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.L.K. and J.V.H.; writing—review and editing, J.V.H. and K.L.K.; visualization, J.V.H.; funding acquisition, K.L.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The Maya research was funded by the National Science Foundation (0964031, 1632338), the NIH (AG 19044-01), the Milton Foundation, Harvard University and the University of Utah.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Utah (#00093510).

Informed Consent Statement

Verbal informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Data Availability Statement

Data are available by request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Baggio, Jacopo A., Shauna Burnsilver, Alex Arenas, James S. Magdanz, Gary P. Kofinas, and Manlio De Domenico. 2016. Multiplex Social Ecological Network Analysis Reveals How Social Changes Affect Community Robustness More than Resource Depletion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113: 13708–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnsilver, Shauna, and James Magdanz. 2019. Heterogeneity in Mixed Economies Implications for Sensitivity and Adaptive Capacity. Hunter Gatherer Research 3: 601–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnsilver, Shauna, James Magdanz, Rhian Stotts, Matthew Berman, and Gary Kofinas. 2016. Are Mixed Economies Persistent or Transitional? Evidence Using Social Networks from Arctic Alaska. American Anthropologist 118: 121–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnsilver, Shauna, Randall B. Boone, Gary P. Kofinas, and Todd J. Brinkman. 2017. Modeling Tradeoffs in a Rural Alaska Mixed Economy: Hunting, Working, and Sharing in the Face of Economic and Ecological Change. The Give and Take of Sustainability: Archaeological and Anthropological Perspectives on Tradeoffs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burt, Ronald S. 2017. Structural Holes versus Network Closure as Social Capital. In Social Capital. Milton Park: Routledge, pp. 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, James S. 1988. Social Capital in the Creation of Human Capital. American Journal of Sociology 94: S95–S120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleran, Heidi. 2020. Market Integration Reduces Kin Density in Women’s Ego-Networks in Rural Poland. Nature Communications 11: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colleran, Heidi, Grazyna Jasienska, Ilona Nenko, Andrzej Galbarczyk, and Ruth Mace. 2015. Fertility Decline and the Changing Dynamics of Wealth, Status and Inequality. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282: 20150287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derex, Maxime, and Robert Boyd. 2016. Partial Connectivity Increases Cultural Accumulation within Groups. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 113: 2982–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dyble, Mark, James Thompson, Daniel Smith, Gul Deniz Salali, Nikhil Chaudhary, Abigail E. Page, Lucio Vinicuis, Ruth Mace, and Andrea Bamberg Migliano. 2016. Networks of Food Sharing Reveal the Functional Significance of Multilevel Sociality in Two Hunter-Gatherer Groups. Current Biology 26: 2017–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eagle, Nathan, Michael Macy, and Rob Claxton. 2010. Network Diversity and Economic Development. Science 328: 1029–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eakin, Hallie. 2005. Institutional Change, Climate Risk, and Rural Vulnerability: Cases from Central Mexico. World Development 33: 1923–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Falco, Salvatore, and Erwin Bulte. 2011. A Dark Side of Social Capital? Kinship, Consumption, and Savings. Journal of Development Studies 47: 1128–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, Mhairi A., and Ruth Mace. 2005. Helpful Grandmothers in Rural Ethiopia: A Study of the Effect of Kin on Child Survival and Growth. Evolution and Human Behavior 26: 469–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, Ricardo. 2001. Indians, Markets, and Rainforests: Theory, Methods, and Analysis. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Godoy, Ricardo, Victoria Reyes-García, Elizabeth Byron, William R. Leonard, and Vincent Vadez. 2005a. The effect of market economies on the well-being of indigenous peoples and on their use of renewable natural resources. Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 121–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, Ricardo, Victoria Reyes-García, Tomás Huanca, William R. Leonard, Vincent Vadez, Cynthia Valdés-Galicia, and Dakun Zhao. 2005b. Why Do Subsistence-Level People Join the Market Economy? Testing Hypotheses of Push and Pull Determinants in Bolivian Amazonia. Journal of Anthropological Research 61: 157–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godoy, R., N. Brokaw, D. Wilkie, D. Colon, A. Palermo, S. Lye, and S. Wei. 2016. Of Trade and Cognition: Markets and the Loss of Folk Knowledge among the Tawahka Indians of the Honduran Rain Forest. Journal of Anthropological Research 54: 219–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1973. The Strength of Weak Ties. The American Journal of Sociology 78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granovetter, Mark. 1983. The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revisited. Sociological Theory 1: 201–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurven, Michael, Adrian V. Jaeggi, Chris Von Rueden, Paul L. Hooper, and Hillard Kaplan. 2015. Does Market Integration Buffer Risk, Erode Traditional Sharing Practices and Increase Inequality? A Test among Bolivian Forager-Farmers. Human Ecology 43: 515–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, Craig. 2004. The Costs and Benefits of Kin: Kin Networks and Children’s Health among the Pimbwe of Tanzania. Human Nature 15: 377–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hadley, Craig, Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, and Emily Fitzherbert. 2007. Seasonal Food Insecurity and Perceived Social Support in Rural Tanzania. Public Health Nutrition 10: 544–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Marcus J, Bruce T Milne, Robert S Walker, Oskar Burger, and James H Brown. 2007. The Complex Structure of Hunter-Gatherer Social Networks. Proceedings of Biological Sciences/The Royal Society 274: 2195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Handwerker, W Penn. 1986. The Modern Demographic Transition: An Analysis of Subsistence Choices and Reproductive Consequences. American Anthropologist 88: 400–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harder, Miriam T, and George W Wenzel. 2012. Inuit Subsistence, Social Economy and Food Security in Clyde River, Nunavut. Arctic 65: 305–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, Joseph, Robert Boyd, Samuel Bowles, Colin Camerer, Ernst Fehr, Herbert Gintis, and Richard McElreath. 2005. ‘Economic Man’ in Cross-Cultural Perspective: Behavioral Experiments in 15 Small-Scale Societies. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, R., and R. Dunbar. 2003. Social Network Size in Humans. Human Nature 14: 53–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hill, Kim R., Robert S. Walker, Miran Božičević, James Eder, Thomas Headland, Barry Hewlett, and A. Magdalena Hurtado. 2011. Co-Residence Patterns in Hunter-Gatherer Societies Show Unique Human Social Structure. Science 331: 1286–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoff, Peter D. 2015. Dyadic Data Analysis with Amen. arXiv arXiv:1506.08237. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, Peter D. 2018. Additive and Multiplicative Effects Network Models. arXiv arXiv:10.1214/19-sts757. [Google Scholar]

- Hoff, Karla, and Arijit Sen. 2006. The Kin System as Poverty Trap? In Poverty Traps. Edited by Samuel Bowles, Steven Durlauf and Karla Hoff. Princeton: Princeton University Press, pp. 96–116. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper, Paul, Simon DeDeo, Ann Caldwell Hooper, Michael Gurven, and Hillard Kaplan. 2013. Dynamical Structure of a Traditional Amazonian Social Network. Entropy 15: 4932–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hooper, Paul, Michael Gurven, Jeffrey Winking, and Hillard Kaplan. 2015. Inclusive Fitness and Differential Productivity across the Life Course Determine Intergenerational Transfers in a Small-Scale Human Society. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inkels, A, and D Smith. 1974. Becoming Modern: Individual Change in Six Developing Countries. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jaeggi, Adrian V., Paul L. Hooper, Bret A. Beheim, Hillard Kaplan, and Michael Gurven. 2016. Reciprocal Exchange Patterned by Market Forces Helps Explain Cooperation in a Small-Scale Society. Current Biology 26: 2180–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jessoe, Katrina, Dale T. Manning, and J. Edward Taylor. 2018. Climate Change and Labour Allocation in Rural Mexico: Evidence from Annual Fluctuations in Weather. Economic Journal 128: 230–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaiser, Bonnie N., Daniel Hruschka, and Craig Hadley. 2017. Measuring Material Wealth in Low-Income Settings: A Conceptual and How-to Guide. American Journal of Human Biology 29: 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, Hillard, Eric Schniter, Vernon Smith, and Bart Wilson. 2012. Risk and the Evolution of Human Exchange. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 279: 2930–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasper, Claudia, and Monique Borgerhoff Mulder. 2015. Who Helps and Why?: Cooperative Networks in Mpimbwe. Current Anthropology 56: 701–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, Jeremy. 2018. Family Ties: The Multilevel Effects of Households and Kinship on the Networks of Individuals. Royal Society Open Science 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, Jeremy M., and George Leckie. 2014. Food Sharing Networks in Lowland Nicaragua: An Application of the Social Relations Model to Count Data. Social Networks 38: 100–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koster, Jeremy, George Leckie, Andrew Miller, and Raymond Hames. 2015. Multilevel Modeling Analysis of Dyadic Network Data with an Application to Ye’kwana Food Sharing. American Journal of Physical Anthropology 157: 507–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Karen L. 2002. Variation in Juvenile Dependence: Helping Behavior among Maya Children. Human Nature 13: 299–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, Karen. 2005. Maya Children: Helpers at the Farm. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer, Karen. 2010. Cooperative Breeding and Its Significance to the Demographic Success of Humans. Annual Review of Anthropology 39: 417–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Karen L. 2011. The Evolution of Human Parental Care and Recruitment of Juvenile Help. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Karen. 2018. The Cooperative Economy of Food: Implications for Human Life History and Physiology. Physiology and Behavior 193: 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kramer, Karen L., and Russell D. Greaves. 2011. Postmarital Residence and Bilateral Kin Associations among Hunter-Gatherers. Human Nature 22: 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, Karen, Joseph Hackman, Ryan Schacht, and Helen Davis. 2021. Does Family Planning Account for Fertility Behavior Across the Demographic Transition? Scientific Reports 11: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Ronald D., and Karen L. Kramer. 2002. Children’s Economic Roles in the Maya Family Life Cycle: Cain, Caldwell, and Chayanov Revisited. Population and Development Review 28: 475–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Nan. 2017. Building a Network Theory of Social Capital. Social Capital 5: 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowes, Sara, Martin Abel, Alberto Alesina, Robert Bates, Natalie Bau, Anke Becker, and Iris Bohnet. 2020. Matrilineal Kinship and Spousal Cooperation: Evidence from the Matrilineal Belt. Available online: https://www.saralowes.com (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Matthews, Ralph, Ravi Pendakur, and Nathan Young. 2009. Social Capital, Labour Markets, and Job-Finding in Urban and Rural Regions: Comparing Paths to Employment in Prosperous Cities and Stressed Rural Communities in Canada. Sociological Review 57: 306–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nettle, D., Mhairi A. Gibson, D. Lawson, and Rebecca Sear. 2013. Human Behavioral Ecology: Current Research and Future Prospects. Behavioral Ecology 24: 1031–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newson, Lesley, and Peter J. Richerson. 2009. Why Do People Become Modern? A Darwinian Explanation. Population and Development Review 35: 117–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Notestein, F.W. 1945. Population: The Long View. Available online: https://www.popline.org/node/517713 (accessed on 2 June 2017).

- Ospina, Raydonal, and Silvia L.P. Ferrari. 2010. Inflated Beta Distributions. Statistical Papers 51: 111–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ospina, Raydonal, and Silvia L.P. Ferrari. 2012. A General Class of Zero-or-One Inflated Beta Regression Models. Computational Statistics and Data Analysis 56: 1609–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poortinga, Wouter. 2006. Social Relations or Social Capital? Individual and Community Health Effects of Bonding Social Capital. Social Science and Medicine 63: 255–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Portes, Alejandro. 1998. Social Capital: Its Origins and Applications in Modern Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology 24: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Power, Eleanor A., and Elspeth Ready. 2019. Cooperation beyond Consanguinity: Post-Marital Residence, Delineations of Kin and Social Support among South Indian Tamils. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 374: 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ready, Elspeth, and Eleanor A. Power. 2018. Why Wage Earners Hunt: Food Sharing, Social Structure, and Influence in an Arctic Mixed Economy. Current Anthropology 59: 74–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, Henri C., Michael E.W. Varnum, and Igor Grossmann. 2017. Global Increases in Individualism. Psychological Science 28: 1228–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scelza, Brooke, and Rebecca Bliege Bird. 2008. Group Structure and Female Cooperative Networks in Australia’s Western Desert. Human Nature 19: 231–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sellers, Kimberly F., and Galit Shmueli. 2010. A Flexible Regression Model for Count Data. Annals of Applied Statistics 4: 943–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shenk, Mary. 2005. Kin Investment in Wage-Labor Economies. Human Nature 16: 81–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shmueli, Galit, Thomas P. Minka, Joseph B. Kadane, Sharad Borle, and Peter Boatwright. 2005. A Useful Distribution for Fitting Discrete Data: Revival of the Conway-Maxwell-Poisson Distribution. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series C: Applied Statistics 54: 127–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinnwell, Jason P., Terry M. Therneau, and Daniel J. Schaid. 2014. The Kinship2 R Package for Pedigree Data. Human Heredity 78: 91–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, Kirsten P., and Nicholas A. Christakis. 2008. Social Networks and Health. Annual Review of Sociology 34: 405–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szreter, Simon, and Michael Woolcock. 2004. Health by Association? Social Capital, Social Theory, and the Political Economy of Public Health. International Journal of Epidemiology 33: 650–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urlacher, Samuel S., Melissa A. Liebert, J. Josh Snodgrass, Aaron D. Blackwell, Tara J. Cepon-Robins, Theresa E. Gildner, Felicia C. Madimenos, Dorsa Amir, Richard G. Bribiescas, and Lawrence S. Sugiyama. 2016. Heterogeneous Effects of Market Integration on Sub-Adult Body Size and Nutritional Status among the Shuar of Amazonian Ecuador. Annals of Human Biology 43: 316–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).