Writing Educational Success. The Strategies of Immigrant-Origin Students in Italian Secondary Schools

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background

2.1. The Unexpected Pathways of Disadvantaged Students

2.2. The Educational Success among Children of Immigrants

2.3. Educational Contexts Matter

3. Methods

3.1. Aims, Hypothesis, and Research Phases

- What meanings do immigrant-origin students attribute to academic success?

- Which characteristics do successful students have?

- Which strategies do students with an immigrant background adopt to achieve educational success?

- Are there any differences between meanings of educational success, narratives and strategies used to achieve it, across different cohorts of migrant students?

3.2. The Sociological Autobiography

3.3. Selection Criteria and Characteristics of the Students Participating in Su.Per.

4. Results

4.1. A Plural Definition of Success: Between Achievement and Progress

Anita. One successful moment in this school was my first 10/10 in Italian. I had received a 10 in other subjects, but never in Italian and, honestly, I never thought it would happen. My whole class applauded, because it is very difficult to get an excellent grade from our Italian teacher. I am also happy for the fact that I have maintained that 10, getting another 10 in the oral exam on Dante.(1.5 G, India)

Destiny. The diversity in being an immigrant is an exceptional gift I have.(2 G, Morocco)

Fatum. Being one of the best students means being different from others. I always try to be the “black sheep”. I try to be the exception, because today we live in a monotonous society and we must try break through this curtain that surrounds everyone.(2 G, Morocco)

Tiana. I want to show […] how I achieved this success. I was very lucky not to give up after a failure. I tried until I overcame the obstacle that prevented me from reaching my goals. Always face insecurities and never stop trying.(1.25 G, Pakistan)

Anastasia. The goal is to overcome one’s limitations or at least to work on one’s weak spots. To obtain the desired result, then, it is not a goal but a transition.(1.5 G, Poland)

Mr. Nobody. I am not a successful student, but I think I have some ambitions. “Things to do in my life” is the name I have given to my list of projects. Teachers say that I am a good student, I prefer to call myself a “student full of hope”.(1.5 G, Philippines)

Georgia. I always try to give my best and when I can I get involved: I am a class representative, I participate in the institute’s Olympics and I help younger children in need.(2 G, Senegal)

Tiana. I used to think that excellent students were the ones who never need help, but now I know that, like everyone, I sometimes need help too.(1.25 G, Pakistan)

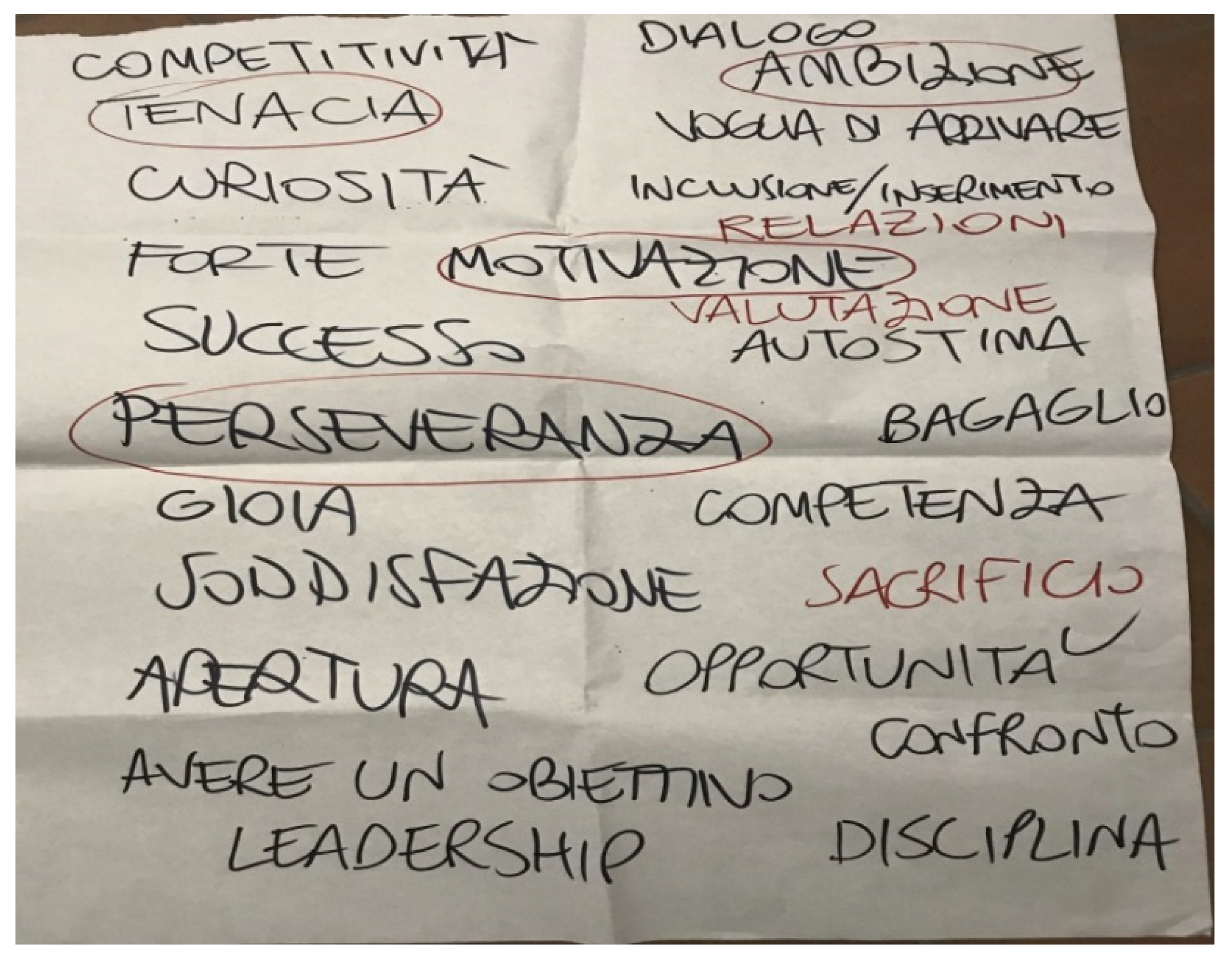

4.2. Portraits of Successful Students with an Immigrant Origin

Ravenclaw. One of my main characteristics is competitiveness: tell me I am not able to do something, and I will show you that the opposite is true. Therefore, the adage “what does not kill you makes you stronger” is true for me.(2 G, Morocco)

Aicha. I never thought I was among the best students. In fact, I just thought I could get away with it. This thing woke me up and made me realize that it is not true that just because you are different you cannot have what they have, it is not that just because you come from another culture you cannot be good at school.(2 G, Senegal)

Mr. Fane. I was the best student in the XI grade, but it was not always a bed of roses.(1.5 G, Romania)

Deep. For me, being a good student does not just mean having excellent grades, it also means having the desire to learn new things, recognizing your weaknesses, and not feeling superior to others.(1.5 G, India)

Willie. I am just doing my duty, like parents do to support a family, my duty is to be a student and I try to do it in the best possible way… it is not like I received a Nobel Prize.(1.5 G, Ghana)

Alishba. Age and knowledge are not important to study. Unlike money, no one can steal knowledge.(1.25 G, Pakistan)

Essmeue. I prefer to think positively, life has already hit me enough.(G2, Ivory Coast)

Hannah. When you work hard to achieve something why not think you deserve such an opportunity? With a lot of patience and work, I managed to get respect. I am very demanding.(1.25 G, Albania)

Molly. Despite all the difficulties, I never thought about leaving school… I was sure that everything would change over time. For this reason, I decided to continue, with a lot of patience.(1.25 G, Moldova)

4.3. Three Strategies for Success: Stand Out, Work Hard, Wait

5. Discussion

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Rebholz, Anil. 2014. Socialization and gendered biographical agency in a multicultural migration context: The life history of a young Moroccan woman in Germany. ZQF 15: 79–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apitzsch, Ursula, and Irini Siouti. 2007. Biographical Analysis as an Interdisciplinary Research Perspective in the Field of Migration Studies. Frankfurt am Main: Johann Wolfgang Goethe Universität. [Google Scholar]

- Apitzsch, Ursula, and Irini Siouti. 2014. Transnational Biographies. ZQF, 11–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Archer, Louise. 2008. The impossibility of Minority Ethnic Educational Success? An Examination of the Discourses of Teachers and Pupils in British Secondary Schools. European Educational Research Journal 7: 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzolini, Davide, and Carlo Barone. 2013. Do they progress or do they lag behind? Educational attainment of immigrants’ children in Italy: The role played by generational status, country of origin and social class. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 31: 82–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azzolini, Davide, Mantovani Debora, and Mariagrazia Santagati. 2019. Italy. Four emerging traditions in immigrant education studies. In The Palgrave Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter A. J. Stevens and A. Gary Dworkin. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, vol. 2, pp. 697–747. [Google Scholar]

- Beltrán Llavador, José. 2002. Ciudadanía y Educación: Lecturas de Imaginación Sociológica. Valencia: Alzira. [Google Scholar]

- Bonizzoni, Paola, Romito Marco, and Cristina Cavallo. 2014. Teachers’ guidance, family participation and track choice: The educational disadvantage of immigrant students in Italy. British Journal of Sociology of Education 37: 702–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1989. La Noblesse d’État. Paris: Minuit. [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1990. The Logic of Practice. Cambridge: Polity Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brinbaum, Yaël, and Annick Kieffer. 2005. D’une génération à l’autre, les aspirations éducatives des familles immigrées: Ambition et persévérance. Education et Formations 72: 507–54. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz, Kathy. 2006. Constructing Grounded Theory. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Maddalena. 2018. The Impact of Ethnicity on School Life: A Cross-National Post-Commentary. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 10: 187–200. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Maddalena, and Mariagrazia Santagati. 2010. Interpreting social inclusion of young immigrants in Italy. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 1: 9–48. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo, Maddalena, and Mariagrazia Santagati. 2017. School Integration as a Sociological Construct: Measuring Multi-ethnic Classrooms’ Integration in Italy. In Living in Two Homes. Edited by Mariella Espinoza-Herold and Rina M. Contini. Bingley: Emerald, pp. 253–92. [Google Scholar]

- Corbetta, Piergiorgio. 1999. Metodologia e Tecniche Della Ricerca Sociale. Bologna: Il Mulino. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum 1: 139–67. [Google Scholar]

- Crul, Maurice. 2013. Snakes and ladders in educational systems: Access to higher education for second generation Turks in Europe. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 39: 1383–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, Maurice, and Jens Schneider. 2010. Comparative integration context theory: Participation and belonging in new diverse European cities. Ethnic and Racial Studies 33: 1249–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, Maurice, and Hans Vermeulen. 2003. The second generation in Europe. International Migration Review 37: 965–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, Maurice, Elif Keskiner, and Frans Lelie. 2016. The upcoming new elite among children of immigrants: A cross-country and cross-sector comparison. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 209–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crul, Maurice, Schneider Jens, Keskiner Elif, and Frans Lelie. 2017. The multiplier effect: How the accumulation of cultural and social capital explains steep upward social mobility of children of low-educated immigrants. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 321–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dicks, Alexander, Dronkers Jaap, and Mark Levels. 2019. Cross-Nationally Comparative Research on Racial and Ethnic Skill Disparities: Questions, Findings, and Pitfalls. In The Palgrave Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education, 2nd ed. Edited by Peter A. J. Stevens and A. Gary Dworkin. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan, vol. 2, pp. 1183–236. [Google Scholar]

- Engzell, Per. 2019. Aspiration Squeeze: The Struggle of Children to Positively Selected Immigrants. Sociology of Education 92: 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eve, Michael. 2015. Immigrant Optimism? Educational Decision-Making Processes in Immigrant Families in Italy. Alessandria: Università del Piemonte Orientale. [Google Scholar]

- Haller, William, Portes Alejandro, and Scott M. Lynch. 2011. Dreams Fulfilled and Shattered: Determinants of Segmented Assimilation in the Second Generation. Social Forces 89: 733–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISMU Foundation. 2021. Report on Migration 2021. Milan: FrancoAngeli. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, Michelle. 2012. Bold choices. How ethnic inequalities in educational attainment are suppressed. Oxford Review of Education 38: 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonsson, O. Jan, and Frida Rudolphi. 2011. Weak Performance-Strong Determination: School achievement and educational choice among children of immigrants in Sweden. European Sociological Review 27: 487–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, Grace, and Marta Tienda. 1995. Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly 76: 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Kasinitz, Philip, Mollenkopf John, Waters Mary C., and Jennifer Holdaway. 2008. Inheriting the City. The Children of Immigrants Come of Age. New York: Russell Sage Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Konyali, Ali. 2014. Turning Disadvantage into Advantage: Achievement Narratives of Descendants of Migrants from Turkey in the Corporate Business Sector. New Diversities 16: 107–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lahire, Bernard. 1994. Les raisons de l’improbable. Les forms populaires de la réussite à l’école élémentaire. In L’éducation prisonnière de la forme scolaire? Edited by Guy Vincent. Lyon: PUL, pp. 73–106. [Google Scholar]

- Lahire, Bernard. 1995. Tableaux de Familles. Heurs and Malheurs Scolaires en Milieu Populaires. Paris: Gallimard/Seuil. [Google Scholar]

- Lahire, Bernard. 2008. De la réflexivité dans la vie quotidienne: Journal personnel, autobiographie et autres écritures de soi. Sociologie et Sociétés 40: 165–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Lahire, Bernard. 2017. Sociological biography and socialisation process: A dispositionalist-contextualist conception. Contemporary Social Science 14: 379–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodigiani, Rosangela. 2020. Religious Belongings in Multicultural Schools: Freedom of Expression and Citizenship Values. In Migrants and Religion: Paths, Issues, and Lenses. Edited by Laura Zanfrini. Leiden: Brill, pp. 676–714. [Google Scholar]

- Maccarini, Andrea. 2016. On Character Education: Self-Formation and Forms of Life in a Morphogenic Society. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 8: 31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Medarić, Zorana, and Mateja Sedmak. 2012. Children’s Voices: Interethnic Violence in School Environment. Ljubljana: Koper Annales University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, Barbara, and Linden West. 2009. Using Biographical Methods in Social Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Mickelson, Roslyn A. 1990. The attitude-achievement paradox among black-adolescents. Sociology of Education 63: 44–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moore, Niamh, Salter Andrea, Stanley Liz, and Maria Tamboukou. 2016. The Archive Project. Archival Research in the Social Sciences. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Morrice, Linda. 2014. The learning migration nexus: Towards a conceptual understanding. European Journal for Research on the Education and Learning of Adults 5: 149–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- OECD. 2018. The Resilience of Students with an Immigrant Background: Factors that Shape Wellbeing. Paris: OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Paba, Sergio, and Rita Bertozzi. 2017. What Happens to Students with an Immigrant Background in the Transition to Higher Education? Evidence from Italy. Rassegna Italiana di Sociologia LVIII: 313–48. [Google Scholar]

- Park, Robert E., and Ernst W. Burgess. 1969. Introduction to the Science of Sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pinson, Halleli, and Madeleine Arnot. 2020. Wasteland revisited: Defining an agenda for a sociology of education and migration. British Journal of Sociology of Education 41: 830–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Lingxin Hao. 2004. The schooling of children of immigrants: Contextual effects on the educational attainment of the second generation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 101: 11920–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Portes, Alejandro, and Rubén Rumbaut. 2001. Legacies. The Story of the Immigrant Second Generation. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rumbaut, Rubén. 2004. Ages, Life Stages, and Generational Cohorts: Decomposing the Immigrant First and Second Generations in the United States. International Migration Review 38: 1160–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagati, Mariagrazia. 2015. Researching Integration in Multiethnic Italian Schools. A Sociological Review on Educational Inequalities. Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 7: 294–334. [Google Scholar]

- Santagati, Mariagrazia. 2018. Turning Migration Disadvantage into Educational Advantage. Autobiographies of Successful Students with an Immigrant Background. RASE. Revista de Sociología de la Educación 11: 315–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santagati, Mariagrazia. 2019. Autobiografie di una generazione Su.Per. Il successo degli studenti di origine immigrata. Milano: Vita e Pensiero. [Google Scholar]

- Schnell, Philipp, and Davide Azzolini. 2015. The academic achievements of immigrant youths in new destination countries: Evidence from Southern Europe. Migration Studies 3: 217–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, Peter A. J., and A. Gary Dworkin. 2019. The Palgrave Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education, 2nd ed. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, Mary Amanda. 2010. Writing with power, sharing their immigrant stories: Adult ESOL students find their voices through writing. TESOL Journal 1: 269–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, William I., and Florian Znaniecki. 1918–1920. The Polish Peasant in Europe and America. Boston: The Gorham Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tsiolis, Giorgos. 2012. Biographical constructions and transformations: Using biographical methods for studying transcultural identities. Papers: Revista de Sociología 97: 113–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Praag, Lore. 2013. Right on track? An explorative study of ethnic minorities’ success in Flemish secondary education. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium. [Google Scholar]

- Van Praag, Lore, Peter A.J. Stevens, and Mieke Van Houtte. 2015. Defining success in education: Exploring the frames of reference used by different voluntary migrant groups in Belgium. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 49: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verhaeghe, Floor, Brach Liebe, Van Houtte Mieke, and Ilse Derluyn. 2017. Structural assimilation in young first-, second-, and third-generation migrants in Flanders. Ethnic and Racial Studies 40: 2728–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vianello, Francesca A., and Angela M. Toffanin. 2021. Young adult migrants’ representation of ethnic, gender and generational disadvantage in Italy. Ethnic and Racial Studies 44: 154–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanfrini, Laura. 2019. The Challenge of Migration in a Janus-Faced Europe. Cham: Palgrave MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Zanfrini, Laura. 2020. Migrants and Religion: Paths, Issues, and Lenses. Edited by Laura Zanfrini. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Min, and Roberto Gonzales. 2019. Divergent Destinies: Children of Immigrants Growing Up in America. Annual Review of Sociology 45: 383–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Self-Presentation. I introduce myself. Main characteristics and qualities. My family. |

| PAST |

| The choice of upper secondary school. |

| The effects of having a migrant background on my past educational career. |

| PRESENT |

| A success that I have achieved. |

| A failure that I have experienced. |

| The effects of having a migrant background on my current educational experience. |

| FUTURE |

| What have I achieved and what do I still want to achieve in my educational path? |

| Personal Information. |

| Pseudonym | Gender | Origin | Attended School |

|---|---|---|---|

| Born in Italy—Second Generation (2 G) | |||

| Aditti | Female | India | Technical Institute |

| Aicha | Female | Senegal | VET |

| Alessia | Female | Albania | VET |

| Alunna | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Anuar | Male | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Aria | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Billy | Male | Morocco | VET |

| Callie | Female | Albania | Lyceum |

| Destiny | Female | Morocco | Lyceum |

| Fatum | Female | Morocco | Technical Institute |

| Georgia | Female | Senegal | Lyceum |

| Ikram | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Jenny | Female | Tunisia | Professional Institute |

| Jessica | Female | India | Lyceum |

| Kaer | Male | Albania | Lyceum |

| Krin | Male | Mauritius | Professional Institute |

| Lisa | Female | China | Lyceum |

| Matt | Male | Senegal | Professional Institute |

| Miriam | Female | Albania | Lyceum |

| Nur | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Rashid | Male | Iran | Lyceum |

| Ravenclaw | Female | Morocco | Lyceum |

| Salvador | Male | Albania | Technical Institute |

| Yasmine | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Yosra | Female | Morocco | VET |

| Arrived during Primary School—1.5 Generation (1.5 G) | |||

| Aisha | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Amna | Female | Morocco | Lyceum |

| Anastasia | Female | Poland | Technical Institute |

| Anita | Female | India | Technical Institute |

| Annael | Female | Romania | Technical Institute |

| Annie | Female | India | Technical Institute |

| Deep | Female | India | Lyceum |

| Desi Girl | Female | Pakistan | Professional Institute |

| El Rubio | Male | Montenegro | Technical Institute |

| Eléna | Female | Romania | Professional Institute |

| Evie | Female | Bosnia | Technical Institute |

| Gianni | Male | Ethiopia | Lyceum |

| Iker | Male | Algeria | Professional Institute |

| Jawhara | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Kalós | Male | Albania | Professional Institute |

| Lovy | Female | India | Professional Institute |

| Malik | Male | Pakistan | Technical Institute |

| Mr. Nobody | Male | Philippines | VET |

| Mr. Fane | Male | Romania | Technical Institute |

| Nina | Female | Ukraine | Technical Institute |

| SaiSai | Male | India | Technical Institute |

| Sammi | Female | Pakistan | VET |

| Sole | Female | Morocco | Professional Institute |

| Sulejman | Male | Albania | Technical Institute |

| Tasfee | Male | Bangladesh | Lyceum |

| Trey | Male | Romania | Technical Institute |

| Willie | Male | Ghana | Technical Institute |

| Arrived during Secondary School—1.25 Generation (1.25 G) | |||

| Alishba | Female | Pakistan | Professional Institute |

| Camilla | Female | Peru | Professional Institute |

| Essmeue | Female | Ivory Coast | Technical Institute |

| Hannah | Female | Albania | Professional Institute |

| Jaspreet | Male | India | VET |

| Leila | Female | Morocco | VET |

| Molly | Female | Moldova | Technical Institute |

| Paki | Male | Pakistan | VET |

| Preeti | Female | India | Professional Institute |

| Quiantrelle | Female | Philippines | Technical Institute |

| Sami | Female | India | Technical Institute |

| Tiana | Female | Pakistan | Professional Institute |

| Torry | Female | Moldova | VET |

| Groups of Students | Attitudes of the Successful Student | Narratives of Success | Success Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Generation | Feel superior to natives React to self-redeem | Competition to excel Defense vs. discrimination | Stand out |

| 1.5 Generation | Be like everyone else Never give up | Equal opportunities Studying as a duty and priority | Work hard |

| 1.25 Generation | Accept downgrade Be patient, trust in the future | Temporary nature of failure Positive thinking | Wait |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santagati, M. Writing Educational Success. The Strategies of Immigrant-Origin Students in Italian Secondary Schools. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050180

Santagati M. Writing Educational Success. The Strategies of Immigrant-Origin Students in Italian Secondary Schools. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(5):180. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050180

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantagati, Mariagrazia. 2021. "Writing Educational Success. The Strategies of Immigrant-Origin Students in Italian Secondary Schools" Social Sciences 10, no. 5: 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050180

APA StyleSantagati, M. (2021). Writing Educational Success. The Strategies of Immigrant-Origin Students in Italian Secondary Schools. Social Sciences, 10(5), 180. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10050180