1. Introduction

Integration is a long, dynamic, and two-way process based on the definition by the

Council of the European Union (

2004). According to

Ager and Strang (

2008), the success of the integration process depends on which indicators are considered while measuring. For that reason, the process becomes complex, multi-dimensional, and multi-directional. They found that although key factors such as citizenship, economy, education, housing, and rights are important, the social connection plays a vital role for a successful integration process at local level (

Strang and Ager 2010).

Habes et al. (

2019) identified “not including Finns in the integration process” as one of the most influential challenges hindering the successful integration process in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia. Thus, the focus of the current paper is to explore the action plans that could facilitate the inclusion of Finns in the integration process of minority groups in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia in order to overcome one of the most influential challenges of the integration process in the region. In this regard, 12 participants from diverse backgrounds were invited to a structured democratic dialogue (SDD) co-laboratory (Co-Lab) to develop a common vision and generate action plans aiming to create a road map for a successful integration process.

In Finland, 51.2% of the 5.2% Swedish-speaking minority population reside in the Ostrobothnia region (

Statistikcentralen 2020a). The region consists of both bilingual and purely Finnish-speaking municipalities and receives a considerable amount of migration, third highest among others, in Finland (

Statistikcentralen 2020b). Vaasa, with a population of nearly 67,000, 70% of whom speak Finnish, 23% Swedish, and 7% other languages as their mother tongue, was chosen as the locality for this study.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

In total, 25 participants from different age groups and sociocultural/educational backgrounds, all knowledgeable about the topic of discussion, were invited to attend a 2-day (20 h) SDD Co-Lab in Vaasa. Both purposive and snowball sampling techniques were used for the selection of the participants in order to ensure that the participants who either participated in the integration process in the past and/or have been involved in the integration process in one way or another were chosen for this Co-Lab. It was clearly stated in the invitation that participation was on a voluntary basis, the whole process would be recorded, and the names of the participants would remain anonymous. There was no compensation offered for attending the Co-Lab; however, lunch and refreshments with snacks were served. In total, 12 out of 25 invited participants attended the Co-Lab. Although all the invited stakeholders/participants were not present, the facilitators agreed to run the Co-Lab believing that the low number of participants would not affect the results of the Co-Lab significantly. Participants were American, British-Finnish, Iranian, Lithuanian, Russian, Serbian, Somalian, and Turkish together with two Finnish and two Swedish-speaking Finns. The participants had also diverse educational backgrounds such as business and economics, computer engineering, education, international relations, psychology, tourism, and hospitality management, and social sciences representing different occupational sectors, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), and political parties. Some of them were also post-graduate students, volunteers, and unemployed persons affiliated with different communities such as an African community, Christian and Muslim communities, a feminist group, and the LGBTQ community. The age group was between 25–40, with 31 as the median age. Seven of the participants were female and five were male.

2.2. Structured Democratic Dialogue (SDD)

Structured democratic dialogue (SDD) (

Christakis and Bausch 2006;

Schreibman and Christakis 2007) was used as a methodology for the Co-Laboratory. This particular methodology was chosen because it aims to bring different stakeholders of the society together in order to discuss and solve the complex problems collectively with the support of a democratic and structured dialogue (

Laouris 2012). By doing so, it provides the participants, who have diverse backgrounds, perspectives, and worldviews, an authentic engagement to develop a shared understanding and consensus for the topic discussed.

The implementation of the SDD methodology includes 10 steps in six well-defined phases (see

Figure 1). In this way, the deeper understanding of the topic and possible solutions can be identified and agreed upon by the participants. This method leads to the development of a common understanding of the different dimensions, and also to the mapping of the influence the ideas have upon each other. Thus, it allows the participants to recognize the root cause of the problem and to propose solutions for it.

The Co-Lab was led by two facilitators. In the beginning of the Co-lab, a presentation about the topic and the aim of the study was given to the participants. The SDD process was explained in detail to the participants by the facilitators. In every session, one facilitator led the discussion and the other one administered the Cogniscope™ system. The Co-Lab took 2 days (20 h) to be completed, and there were no observers in the room. However, the sessions were recorded for transcription purposes.

At the first phase of the Co-Lab, a triggering question (TQ) is formulated based on an identified complex problem. This constitutes the first phase. With a single statement, the participants, one by one, deliver possible ideas to respond to the TQ during phase two. The proposed ideas by participants are recorded in Cogniscope™ exactly as they are uttered. In the same phase, the participants are invited to clarify their ideas to other participants. The clarifications are recorded in order to be transcribed exactly as they are and minimize to zero the risk of misinterpretations between the participants or the possibility of a biased analysis by the researchers. The other participants can only seek clarification without criticism if the explanation is not clear enough. They do not comment on them.

In phase three, the similarities and the common features of all ideas is discussed in-depth by the participants. The participants group the ideas into clusters collectively by following a bottom-up approach and common agreement. The clusters that are generated and named by the participants are registered in the Cogniscope™ system and displayed on the wall.

After the clustering, in phase four, the participants are invited to vote individually for five out of the total set of ideas that they believe to be the most important ones helping to solve the TQ. The ideas which receive at least two votes move to the next and most important phase.

In phase five, participants are challenged with two ideas at a time and invited to discuss them to decide whether one influences the other. The impact or relation is recorded only when a large majority (75%) supports the influence. In the case the votes fall evenly or a majority is not reached, the participants revote following a constructive debate. An influence map is constructed during this process, after the connections among the ideas are voted and agreed upon by the participants. The influence map reflects the shared understanding and the agreement among the participants. In this way, the SDD process helps participants to recognize the relationship among their different ideas and to develop a shared understanding with consensus. The term ‘influence’ in the SDD methodology refers to the implementation of an action, which will have the highest impact on resolving the TQ.

In the last phase, SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time specific) actions are defined by discussing the influence map in a greater detail in order to address the root causes of the problem.

3. Results

During the phase of generating ideas, the participants were invited to state their ideas one by one. This process continued until all ideas were gathered. Equal time was given to every participant each time when their turn came to generate their ideas/action plans. All ideas/action plans were registered in the CosniscopeTM system. In this way, each idea was given equal importance. This technique countered the groupthink phenomenon, because each participant had the opportunity to present their ideas/action plans regardless of how powerful or strongly different the other participants’ opinions were. In total, 66 ideas/actions were generated by the participants in the form of a single statement responding to the Triggering Question: “What actions (political, educational, financial, sociocultural) can be taken in order to facilitate the inclusion of Finns in the integration process of minority groups in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia?”.

After all ideas were defined, printed and displayed on the screen, the participants were invited to explain their ideas to the rest of the group one by one. The goal of this phase was to allow all participants to have the same understanding and interpretation of the idea/action generated by its owner. The clarifications of all ideas, however, are not included in this paper due to concerns about space, but they are available upon request.

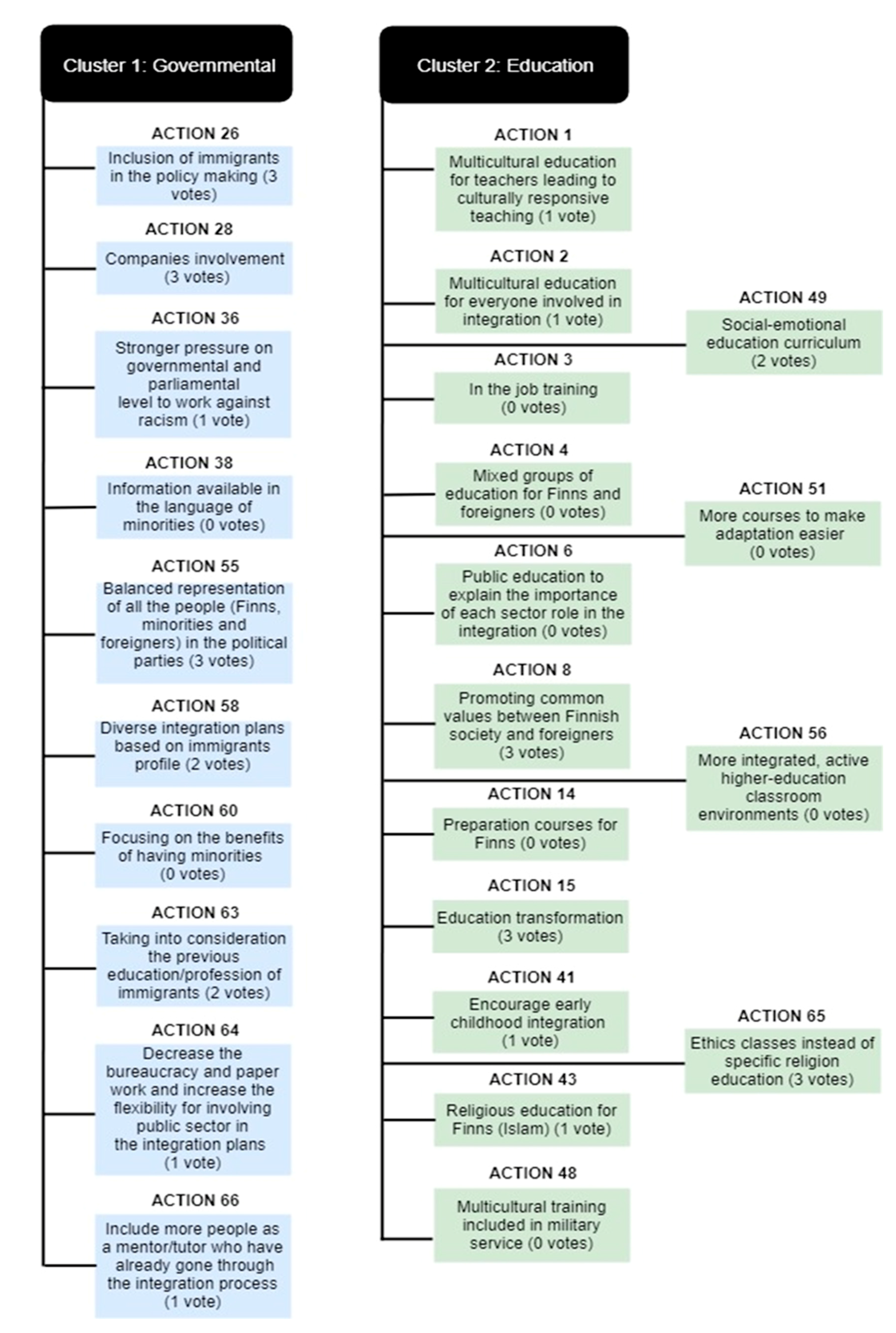

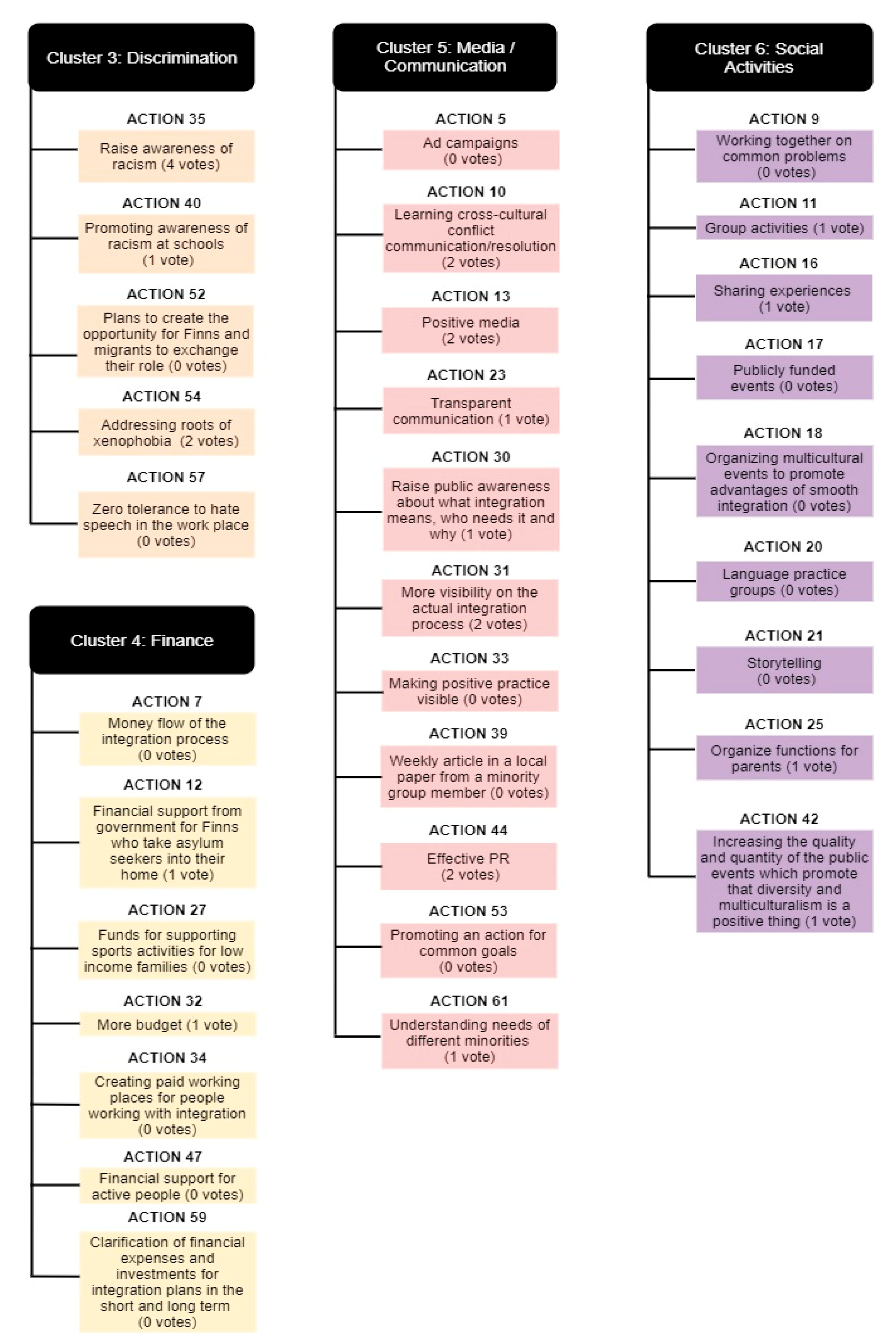

The next phase involved the categorization of the proposed ideas/actions into clusters using a bottom-up approach. The participants were encouraged to explore the similarities and common aspects of the ideas/actions by discussing and comparing them. When the participants collaboratively identified the common attributes among the ideas/actions, they placed them in the same cluster. The participants clustered the 66 ideas/actions into eight categories (see

Figure 2,

Figure 3 and

Figure 4) namely: Cluster 1: Governmental; Cluster 2: Education; Cluster 3: Discrimination; Cluster 4: Finance; Cluster 5: Media/Communication; Cluster 6: Social Activities; Cluster 7: Organizations; Cluster 8: Finnish Individuals.

Overall, the Education cluster was the category that generated the highest number (15) of ideas, followed closely by the Media/Communication cluster with 11 ideas. A considerable number of ideas was categorized under Cluster 1: Governmental, and Cluster 6: Social Activities, which contained 10 and 9 ideas, respectively. Cluster 4: Finance and Cluster 7: Organizations had seven ideas, while five ideas were distributed to the Cluster 3: Discrimination. Finally, two ideas were sorted into the Cluster 8: Finnish Individuals being the cluster with the smallest number of ideas of the Co-Lab.

In the fourth phase, the participants were asked to vote for the five most important ideas/actions that they thought they could resolve the TQ in the best way possible. In total, 20 actions received one vote, and 16 actions (see

Table 1 and

Appendix A for the clarifications) gathered at least two votes and more. Only the actions that received at least two votes were used for the structuring phase, where the interrelations among generated ideas/actions identified.

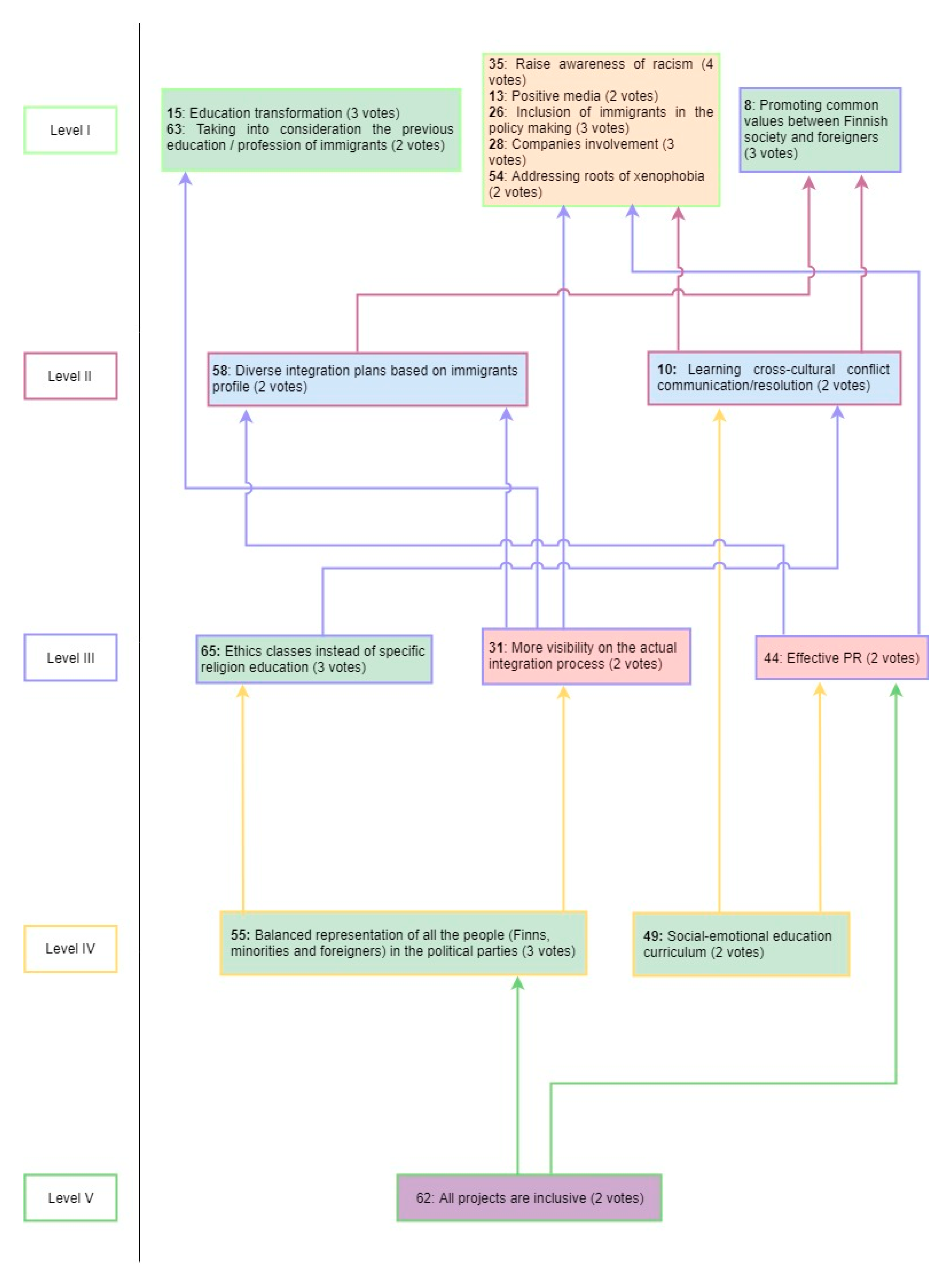

In phase five, the participants discussed thoroughly the interrelation between the pairs of ideas/actions and voted on the specific relations between them for the structuring. In order to establish the influence map, the participants were asked whether the implementation of action A would significantly help us to implement action B or not. When the vote of the great majority (75%) of participants was positive, the relative influence of the first action on the other was determined. The influence map (see

Figure 5), which is a roadmap for the solution of the TQ, was created after the evaluation of all actions in the same manner.

The influence map contains five different levels. The most influential actions are the ones which are situated at the bottom levels of the map, particularly at level V and IV. In this way, the implementation of the action plans at the base levels of the map will significantly influence or ease the implementation of the upper-levels’ action plans. It should be observed that actions only on Level I share the same box unlike the other levels, where all are having an independent box. This means that actions with a shared box are mutually influencing each other, whereas actions on the same level with an independent box are not influencing each other but influence only upper levels.

According to the influence map, the most influential actions among the others are: Action #62: All projects are inclusive, Action #55: Balanced representation of all the people (Finns, minorities and foreigners) in the political parties, and Action #49: Social-emotional education curriculum.

At the upper levels of the map, the other influential proposals included:

Action plans related to education such as Action #65: Ethics classes instead of specific religion education; Action #8: Promoting common values between Finnish society and foreigners; and Action #15: Education transformation.

Actions plans associated with media/communication: Action #31: More visibility on the actual integration process; Action #44: Effective PR; Action #10: Learning cross-cultural conflict communication/resolution; and Action #13: Positive media.

Action plans suggested for the government were Action #58: Diverse integration plans based on immigrants’ profile; Action #26: Inclusion of immigrants in the policy making; Action #28: Companies involvement; and Action #63: Taking into consideration the previous education/profession of immigrants.

Action plans which are referring to discrimination were Action #35: Raise awareness of racism; and Action #54: Addressing roots of xenophobia.

4. Discussion

During the Co-Lab, the participants categorized 66 action plans into eight clusters, which, if implemented, could possibly help the inclusion of Finns in the integration process of minority groups in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia. These clusters covered a wide range of topics from governmental activities, education, finance, media/communication, to topics related to social activities, organizations, discrimination, and Finnish individuals.

Participants mutually agreed that when organizations such as civil society organizations, community-based local associations, and non-governmental organizations have projects or programs, they should include all the groups, rather than focusing on only specific group(s). In this way, both majority and minority groups can have an opportunity to interact with one another and to develop mutual understanding toward each other’s values, traditions and way of life. Thus, integration, which is a dynamic and two-way process of mutual accommodation, may be accomplished. This fact explains why Action #62: All projects are inclusive turned out to be the most influential action of the whole Co-Lab despite being voted by only two participants during the voting phase.

Action #55: Balanced representation of all the people (Finns, minorities, and foreigners) in the political parties, which is situated at level IV on the influence map and related to policies, regulations, and governmental activities was also considered very important and influential by the participants. The cluster targeting governmental activities was perceived as the most significant one in terms of the number of votes received by the participants. This shows that representation of the minority groups in the decision-making mechanisms such as political parties, governmental offices, and parliament, will increase their visibility in the society, and it will also help them to impact on policies and decisions at a governmental level. Thus, working together with the majority group will facilitate the cooperation and collaboration among the groups.

Education was another important cluster according to the participants, since it contained the highest number of proposed actions. It was also the second most popular cluster in terms of votes. Action #49: Social-emotional education curriculum was considered one of the most influential actions, situated at level IV on the influence map. Education in general and the social-emotional education curriculum in particular plays a vital role in order to develop both cognitive and emotional competences for children (

Cefai et al. 2018). As

Cefai et al. (

2018) points out, this provides the communities inclusion, social cohesion, and harmonious relationships, as well as positive attitudes toward cultural diversity and social justice. In this way, a social-emotional education curriculum helps the children to raise the awareness of both themselves and of society, and to have empathy and tolerance toward others starting from a young age, even though children come from different backgrounds.

At the upper level of the map, the actions related to media/communication, discrimination, education, and governmental activities are situated. Participants believed that using media and communication channels would contribute to the raising of awareness among the diverse community groups, and it may lead to an increase in the visibility of the minority groups in the society. In this way, the majority group will recognize the minority groups as part of the society, and contribute to the development of mutual understanding of one another’s cultures.

Action #35: Raise awareness of racism (4 votes), which received the highest number of votes, was situated at the top level of the map. This means that participants individually, when voting, believed that this action was one of the most important ones to address the triggering question. However, when the participants collectively discussed the relation of this action to other actions during the structuring phase of the map, they realized that this action was not the most influential one. This fact is referred to as the erroneous priority effect (

Dye 1999). Although raising awareness of racism is important, it will not solve the problem unless both the majority and minority groups will take part in the same projects and programs, be represented equally in proportional terms in politics, and raise their children with socio-emotional competences. In other terms, this particular action could be considered as the overarching target of the map of influence in the sense that it will be one of the last actions to be executed to have the whole map implemented.

According to the participants, clusters related to finance, social activities and Finnish individuals were not considered as a big influence for facilitating Finns to be part of the integration process. That is the reason why the action plans in these clusters did not take place on the influence map.

5. Conclusions

Habes et al. (

2019) found that not including Finns in the integration process was one of the most influential challenges that hinders the integration process in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia. In order to overcome this challenge, the participants proposed 66 action plans categorized under eight clusters in order to include Finns in the integration process.

Based on the responses of the participants, it was found that civil society organizations such as associations and NGOs play a vital role in bringing both majority and minority groups together in their projects. In this way, both groups could have the chance to overcome their prejudice and stereotypes, and to start to develop a common understanding and tolerance toward each other. When these organizational projects are supported by equal representation (in proportional terms) at the governmental level, such as in political parties, parliament, and local governmental offices, and by a socio-emotional educational curriculum, it will enhance the social cohesion in the society where inclusion, cultural diversity, and social justice are promoted. Thus, based on the results of the SDD Co-Lab, one of the challenges of integration could possibly be overcome.

The results presented in this article are based on a SDD Co-Lab conducted in Vaasa with a particular region in mind with 12 participants. The relatively low number of participants, in addition to the narrow representation of some minority communities, are limitations of this study. In order to make generalizations to the Finnish society-at-large and eventually contribute toward policy recommendations, further SDD Co-Labs are needed to be implemented with participants of a wider range of background (such as the Romani, and the Iraqi) and a wider age range of the stakeholders.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.H.; methodology, H.H., and A.A.; software, H.H., and A.A.; formal analysis, H.H.; data curation, H.H.; writing—original draft preparation, H.H.; writing—review and editing, K.B., and A.A.; supervision, K.B.; funding acquisition, H.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Svenska Kulturfonden (the Swedish Culture Foundation) kindly supported the first author with a grant (grant number 139817) for research leading to this publication.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Yiannis Laouris at Future Worlds Center (Cyprus Neuroscience and Technology Institute) in Nicosia, Cyprus gave his support and provided the usage of the CogniScopeTM system software for the implementation of the Structured Democratic Dialogue methodology for this Co-Laboratory, which is gratefully acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Clarification of Actions which Received at Least Two Votes

Appendix A.1. Action #8: Promoting Common Values between Finnish Society and Foreigners

Promoting the common values of both the Finnish society and foreigners, so they might see that they are not so different from each other. In the end, Finnish society might not be so scared or hesitant to be merged with the immigrants or the minorities.

Appendix A.2. Action #10: Learning Cross-Cultural Conflict Communication/Resolution

We all have encountered conflicts on a daily basis. The way we solve them, don’t solve them or ignore them depend on our cultural background. It is very important to know how different cultures or cultural groups solve their conflicts; what kind of methods and approaches they use. If we are able to learn about how we communicate with each other, especially in conflict situations such as at work, with partners etc., we could have more positive communication and reach a better outcome. Measuring the success of this action could be done by the employment office or social services by observing what’s happening in the community; whether the people are having more positive communication or more clashes.

Appendix A.3. Action #13: Positive Media

The media is one way to reach the older generations who might not be able to be involved with the minority group or person. They [minority groups] think that a lot of issues come from that separation [between older generations and the minority groups], because the older generations don’t have access to the positive media, which portray the minority group in a more positive way. This positive media could start to erase some presumptions of older generations.

Appendix A.4. Action #15: Education Transformation

People arriving here [Finland] already have an education or some kind of training. However, in Finland, this [education or training] is very hard to get accepted. So, there should be some way that you [people who arrived in Finland] could get some extra courses and certification in order to work here. For example, the education from certain countries is not accepted. Even though it is often said that Finland needs more doctors, a doctor from another country has to wait for some time to work here. The governmental offices, which issue the certification, should adjust the rules of what is accepted here; why the education of some countries is different, and how, in this way, people’s education can be certified better. This process [adaptation of education and certifications] should be adopted by the government and educational system.

Appendix A.5. Action #26: Inclusion of Immigrants in the Policy Making

When making decisions, immigrants are not part of the policy making. The immigrants are actually the ones who are experts in their own struggles. So, if we are not having them in the process of this policy making, then we are just making decisions which do not work for them. This [action] can be implemented by the government and municipalities since they are the ones responsible for policy making.

Appendix A.6. Action #28: Companies Involvement

Integration does not finish after the integration plan. It’s the government’s job. However, afterwards, you [people in the integration process] have to find a workplace. The companies also should be involved in this process and increase their trust towards the foreigners.

Appendix A.7. Action #31: More Visibility on the Actual Integration Process

More Finns should have better understanding what the actual integration process is. At the moment, Finnish people understand the integration process as a language course and maybe something else. There is no understanding what the integration process consists of. So, there should be more visibility on the process. The government and municipalities can do that [increase the visibility].

Appendix A.8. Action #35: Raise Awareness of Racism

This is important because some Finns don’t know what the actual racist comments are; or like they can have a conversation and they think it is ok to say these [racist comments] things, but if they know what is ok and what is not, they would actually see themselves from the other person’s point of view… How racist these comments are, how they silently accept these, and how they affect the other person. This can be done with raising awareness campaigns, such as #metoo in a way, and also, with the help of the media to educate people.

Appendix A.9. Action #44: Effective PR

Even though there are many activities by the organizations, somehow not everybody- both minorities and the Finnish people knows about them. When one organization has some events, only the same people attend these events, and we cannot fully reach those people who are actually racist, because they go to their own events. Effective PR means that the integration activities should be promoted to different people with different worldviews. While having all these activities, everyone should attend them. Media and organizations themselves should try to reach different groups in order to promote these activities.

Appendix A.10. Action #49: Social-Emotional Education Curriculum

In order for long-term changes to happen, you have to really start with schools and children since their minds are still developing and open to adaptation. Before, we had talked about culturally responsive teaching, which is more focusing on educating students about different cultures and making the classrooms focus on more student-based learning. However, having a social-emotional curriculum is proven by studies to be effective and it would also benefit both students and minority groups. For example, a program we had in the US did help to create a social-emotional vocabulary that was consistent throughout the school. By using this [social-emotional vocabulary], we can talk about empathy; what it is like to walk in somebody else’s shoes. There were also videos [shown to the students] together with it [social-emotional vocabulary]. There are programs which are effective. For example, such a program [social-emotional curriculum] was used in one of the schools in Chicago. There was so much violence, so they took away metal detectors and put counselors [instead], as well as had certain programs. Consequently, the amount of violence decreased significantly, and the success of the students’ outcome increased. Thus, having that kind of curriculum for emotional needs and preventing bullying will certainly help students.

Appendix A.11. Action #54: Addressing Roots of Xenophobia

Finnish people should make an effort and rely on research not to take fear of strangers as a fact. Why this [xenophobic behavior] is happening? Are you [Finnish people] scared that you are not going to have enough jobs, or that you will lose your culture, or what’s the issue? What exactly can be done to make you feel more secure in your job with other cultures?… There must be research on xenophobia, and how to address this issue, not just taking facts to resolve this issue.

Appendix A.12. Action #55: Balanced Representation of all the People (Finns, Minorities and Foreigners) in the Political Parties

Everybody should be represented in the parliament and in the government. All the minorities should be [represented] there. Now, it [representation of minorities] is not present there and it is hard to achieve. For example, She [foreign female person in politics] is an inspiration to the other immigrant women, who come to Finland and work really hard to get into that level where they can be actually in the governing body and making an influence on decision making in politics and policy making. She represents not only African women, but also all the immigrant women in Finland, as well as inspiring the local women. So, we [Finnish people] should encourage as many foreign people as possible to go out there and speak up, because they are not only speaking up for themselves, but for others too.

Appendix A.13. Action #58: Diverse Integration Plans Based on Immigrants’ Profile

There is an integration plan for all the immigrants, and we should remember that people come from different backgrounds. However, the same integration plan is applied to all of them. So, this [immigrants’ background] should be taken into consideration and the integration plans should be developed according to their backgrounds.

Appendix A.14. Action #62: All Projects Are Inclusive

We [Finnish People] should not have or manage the projects for immigrants separately. They should be part of the projects. For example, if there is a program or a project for people, we should understand that it must include not only Finns, but also immigrants. They [immigrants] should also take part in that program. So, whatever projects we [Finnish people] have, they should be open for everyone and include all the groups.

Appendix A.15. Action #63:Taking into Consideration the Previous Education/Profession of Immigrants

My father was in the military and in the police force in Somalia. When he came here [Finland], he studied Swedish. He wanted to work in the police force, but he couldn’t get accepted. They [employment office] sent him to another place instead; somewhere not related to his profession. It is not encouraging. So, they [employment office staff] need to consider this [people’s education/profession] to encourage people to find work related to their education or profession. They [employment office staff] should appreciate especially the minorities with different skills even though they haven’t had the Finnish education.

Appendix A.16. Action #65: Ethics Classes Instead of Specific Religion Education

In each school, you [school officials] are not separating kids based on their religious beliefs. You have all kids taking the same class called “Ethics” where you teach them about all religions equally. So, you wouldn’t say in the Finnish context: Christianity is better than Islam, and anything else. However, the school should instead present them [children] all religions, what they are and what these religions represent. This can be the understanding of the different groups rather than separate cases. Everybody gets information about them [all religions]. So, ethics classes instead of religion education should be compulsory to all children in the schools.

References

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies 21: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cefai, Carmel, Paul A. Bartolo, Valeria Cavioni, and Paul Downes. 2018. Strengthening Social and Emotional Education as a Core Curricular Area across the EU: A Review of the International Evidence. NESET II Report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. Available online: https://www.um.edu.mt/library/oar//handle/123456789/29098 (accessed on 17 June 2020).

- Christakis, Alexander N. 1996. A people science: The CogniScope system approach. Systems: Journal of Transdisciplinary Systems Sciences 1: 16–19. [Google Scholar]

- Christakis, Alexander N., and Kenneth C. Bausch. 2006. How People Harness Their Collective Wisdom and Power to Construct the Future in Co-Laboratories of Democracy. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Council of the European Union. 2004. 2618th Council Meeting: Justice and Home Affairs. Brussels: Council of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Dye, Kevin. 1999. Dye’s law of requisite evolution of observations. In How People Harness Their Collective Wisdom and Power. Edited by Alexander N. Christakis and Kenneth C. Bausch. Greenwich: Information Age Publishing, pp. 166–69. [Google Scholar]

- Flanagan, Thomas R., and Alexander N. Christakis. 2009. The Talking Point: Creating an Environment for Exploring Complex Meaning. Charlotte: Information Age Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Janis, Irving L. 1982. Groupthink: Psychological Studies of Policy Decisions and Fiascoes. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. [Google Scholar]

- Habes, Hasan, Kaj Björkqvist, and Andreas Andreou. 2019. Examining the challenges of integration in Swedish-speaking Ostrobothnia: Using the structured democratic dialogue process as a tool. European Journal of Social Science Education and Research 6: 7–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouris, Yiannis. 2012. The ABCs of the science of structured dialogic design. International Journal of Applied Systemic Studies 4: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouris, Yiannis, and Alexander N. Christakis. 2007. Harnessing collective wisdom at a fraction of the time using structured dialogic design process in a virtual communication context. International Journal of Applied Systemic Studies 1: 131–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laouris, Yiannis, and Marios Michaelides. 2017. Structured democratic dialogue: An application of a mathematical problem structuring method to facilitate reforms with local authorities in Cyprus. European Journal of Operational Research 268: 918–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schreibman, Vigdor, and Alexander N. Christakis. 2007. New agora: New geometry of languaging and new technology of democracy: The structured design dialogue process. International Journal of Applied Systemic Studies 1: 15–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Statistikcentralen. 2020a. Population according to Language 1980–2019. Helsinki: Statistics Finland. Available online: http://www.stat.fi/til/vaerak/2019/vaerak_2019_2020-03-24_tau_002_en.html (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Statistikcentralen. 2020b. Official Statistics of Finland (OSF): Preliminary Population Statistics. Appendix Table 2. Preliminary Vital Statistics by Region 2020 and Change Compared to 2019 Final Data, Quarter 1–2. Helsinki: Statistics Finland. Available online: http://www.stat.fi/til/vamuu/2020/06/vamuu_2020_06_2020-07-23_tau_002_en.html (accessed on 1 July 2020).

- Strang, Alison, and Alastair Ager. 2010. Refugee integration: Emerging trends and remaining agendas. Journal of Refugee Studies 23: 499–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whyte, William H. 1952. Groupthink. Fortune 45: 145–46. [Google Scholar]

| Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).