Job Attributes and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of Sex Work and Hairstyling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Sex Work and Hairstyling: Similarities

1.2. Sex Work and Hairstyling: Differences

1.3. Work and Mental Health

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample and Data Collection

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Dependent Variable: Mental Health

2.2.2. Independent Variables

Job Attributes

2.2.3. Control Variables

2.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Statistics

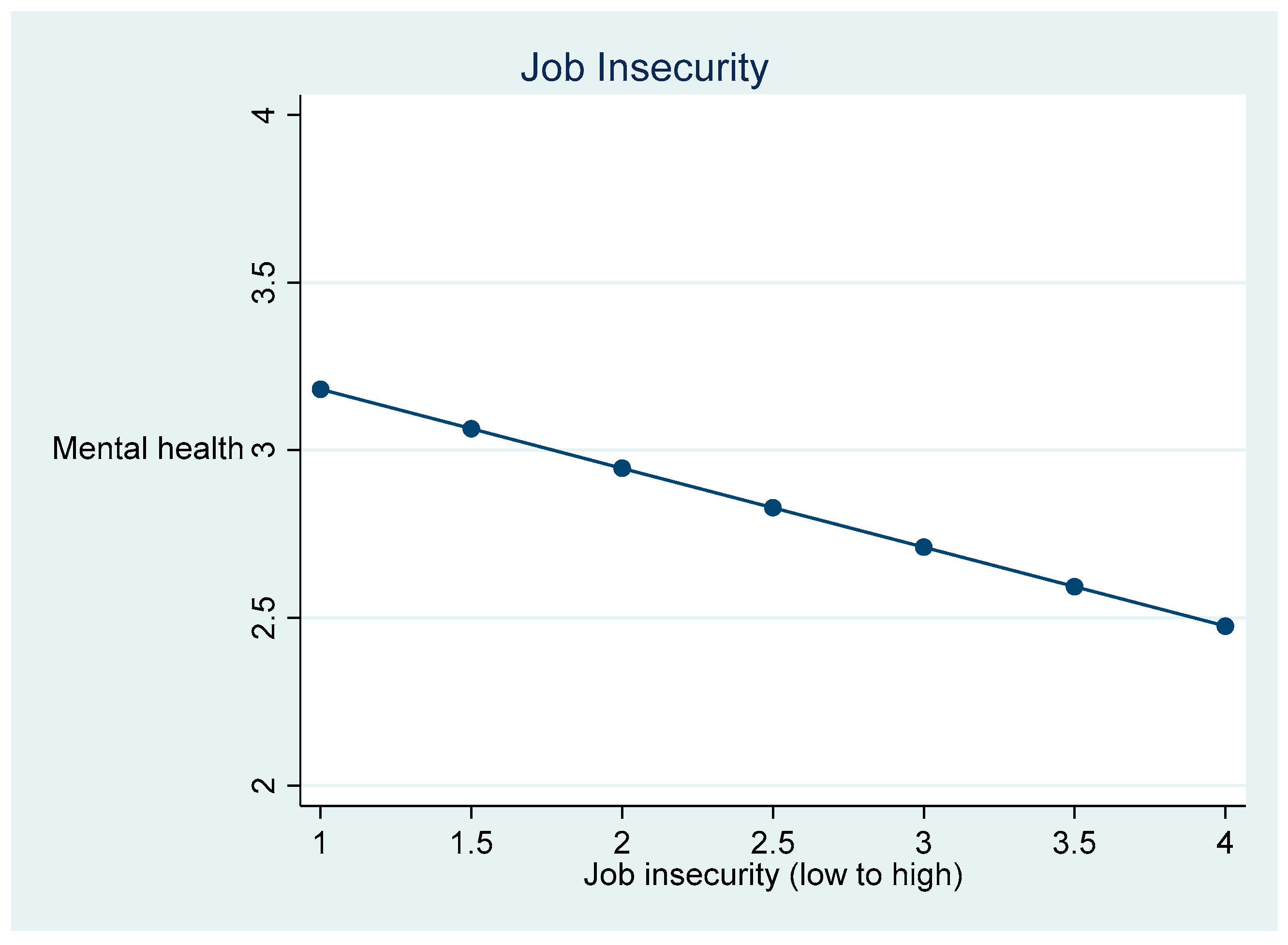

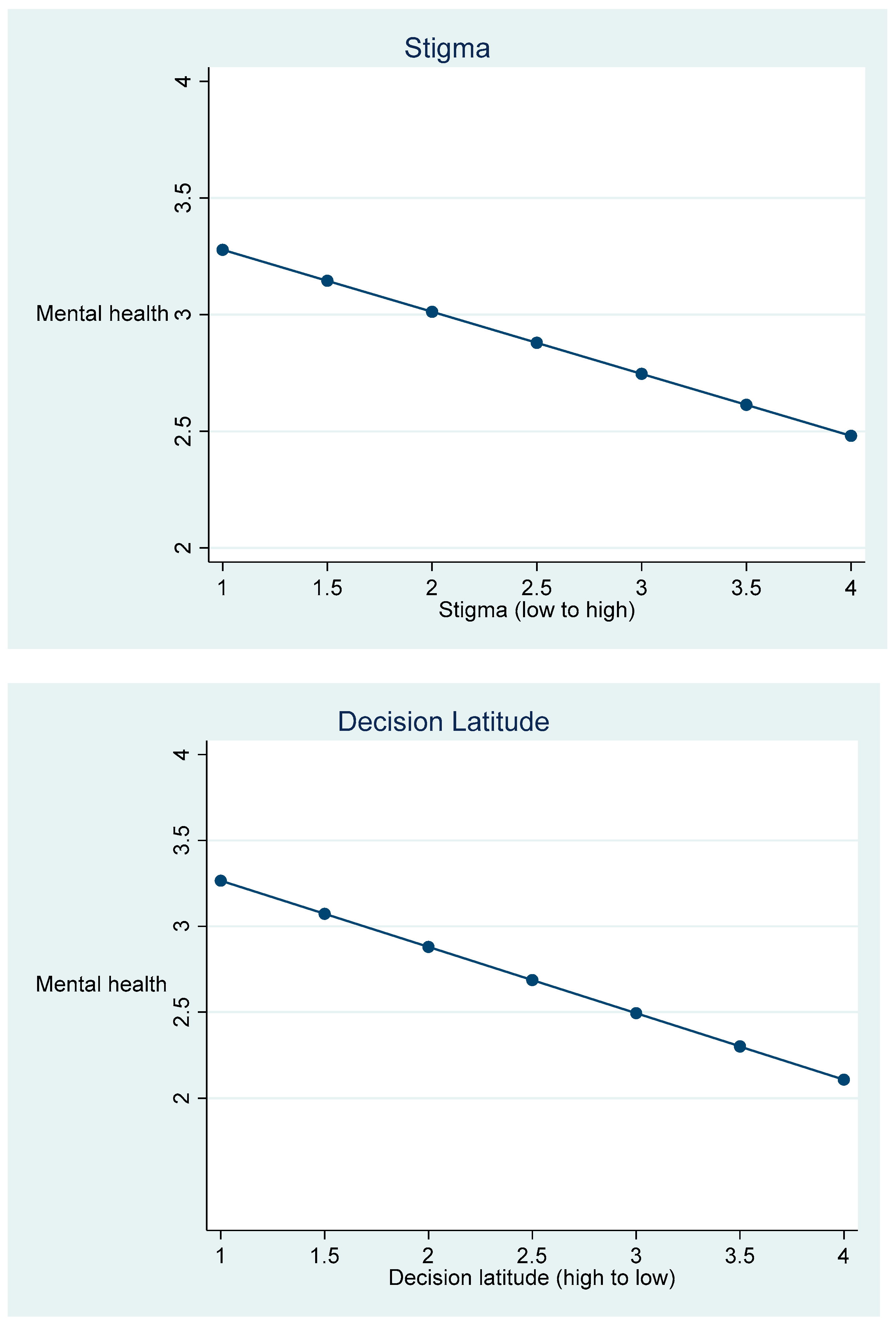

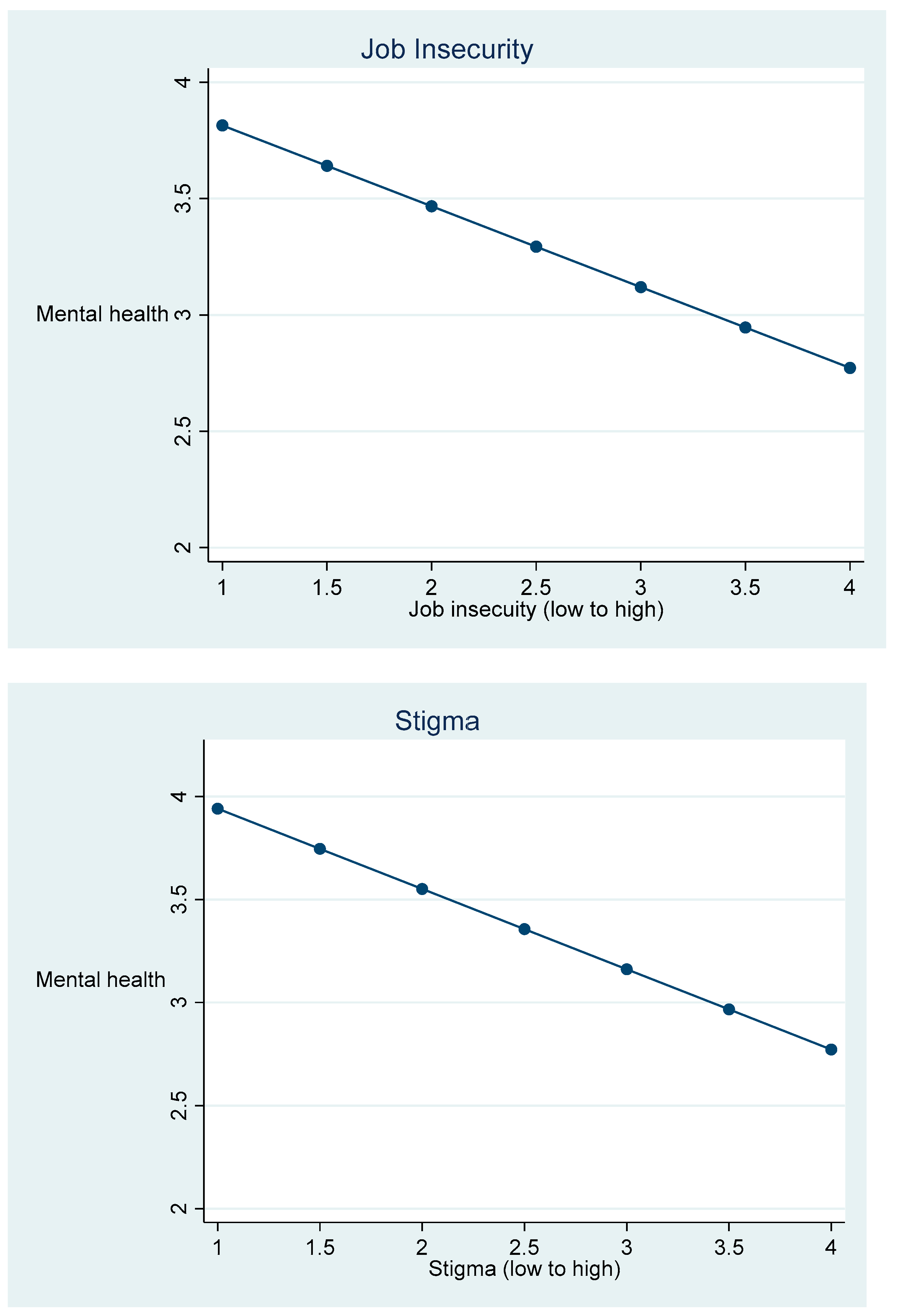

3.2. Multivariable Analyses

4. Discussion

Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Health (measured waves 1–4) | |

| Overall mental health | In the last four months how would you rate your mental health? 1 = Poor 2 = Fair 3 = Good 4 = Very good 5 = Excellent; How often have you been feeling unwell mentally? 1 = Always/chronically 2 = Very often 3 = Sometimes 4 = Not often 5 = Never |

| Job Attributes (measured wave 2) | |

| Self-employed | Are you currently self-employed? 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Income | Logged monthly income from wages/tips from primary job |

| Insecurity | (1) Sometimes people permanently lose jobs they want to keep. How likely is it that during the next couple of years you will lose your present job with your employer? 1 = Not at all likely 2 = Not too likely 3 = Somewhat likely 4 = Very likely; (2) How steady is your work? 1 = Regular and steady 2 = Seasonal 3 = Frequent layoffs 4 = Both seasonal and frequent layoffs; (3) During the past year, how often were you in a situation where you faced a job loss or layoff? 1 = Never 2 = Faced the possibility once 3 = Faced the possibility more than once 4 = Constantly or actually laid off; (4) My job security is good 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Disagree 4 = Strongly disagree |

| Little decision latitude | (1) My job requires that I learn new things; (2) My job requires me to be creative; 3) My job allows me to make a lot of decisions on my own; (3) My job requires a high level of skill; (4) On my job, I have very little freedom to decide how I do my work (reverse coded); (4) I get to do a variety of different things on my job; (5) I have a lot of say about what happens on my job; (6) I have an opportunity to develop my own special abilities 1 = Strongly agree 2 = Agree 3 = Disagree 4 = Strongly disagree |

| Psychological demands | (1) My job requires working very fast; (2) My job requires working very hard; (3) I am free from conflicting demands that others make (reverse coded); (4) I am not asked to do an excessive amount of work (reverse coded); (5) My job involves a lot of repetitive work 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly agree |

| Customer hostility | I am subject to hostility or abuse from clients or customers. 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Neither agree of disagree 4 = Agree 5 = Strongly agree |

| Stigma | (1) I have applied for, but have been refused an apartment when I could afford it; (2) I have applied for, but I have been refused a bank loan or other credit; (3) How often do doctors say anything about the work you do? (4) How often do nurses say anything about the work you do? 1 = Never 2 = Seldom 3 = Sometimes 4 = Often 5 = Very often (5) Doctors usually treat me with respect (reverse coded); (6) Nurses usually treat me with respect (reverse coded); (7) People think I am an intelligent person (reverse coded); (8) My family accepts me as I am (reverse coded); (9) People shy away from me when they get to know me; 1 = Strongly disagree 2 = Disagree 3 = Agree 4 = Strongly agree |

| Control Variables | |

| Time-varying (measured waves 1–4) | |

| Health enhancing behaviors | 1 point (to a maximum of 6) for each of the following: exercising more, quitting or reducing smoking, drinking less alcohol, changing diet or eating habits, taking vitamins, or other, unlisted behaviors |

| Health care use | 1 point (to a maximum of 4) for each of the following: physician, physician specialist, psychiatrist, or hospital emergency care |

| Living with spouse/partner | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Children | Number of children living with respondent |

| Substance use 1 | How often in the last four months did you consume (1) alcohol (2) marijuana? 0 = Never, 1 = Less than once a month, 2 = Twice a month, 4 = Once a week, 8 = Twice a week, 30 = Daily or more |

| Substance use 2 | How often in the last four months did you consume (1) cocaine; (2) club drugs (e.g., ecstasy); (3) non-prescribed prescription drugs (e.g., OxyContin); (4) crystal methamphetamine; (5) heroin? 0 = Never, 1 = Less than once a month, 2 = Twice a month, 4 = Once a week, 8 = Twice a week, 30 = Daily or more |

| Time-invariant (measured wave 1) | |

| Gender | 0 = Male 1 = Female |

| Sexual minority | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Racial minority | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Nativity | 0 = Native 1 = Immigrant |

| Non high school graduate | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| High school graduate | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Some college | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| College graduate | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Ever unemployed | 0 = No 1 = Yes (at any time during study) |

| Access to health care | 0 = No 1 = Yes |

| Country | 0 = Canada 1 = U.S. |

| Childhood economic insecurity | While you were growing up, were your parents/guardians able to pay for: (1) Basic necessities (like food, clothing or rent); (2) Things you needed for school (like school supplies, going on local field trips, etc.); (3) Recreational activities (like playing soccer or other sports, movies, eating out, vacation, or music lessons)? 1 = Rarely/never 2 = Some of the time 3 = Half of the time 4 = Most of the time 5 = Almost always/always |

| Childhood abuse | Count of the number of years (from birth to 18) that the respondent was the victim of sexual abuse |

References

- Abel, Gillian. 2011. Different stage, different performance: The protective strategy of role play on emotional health in sex work. Social Science & Medicine 72: 1177–84. [Google Scholar]

- Abel, Gillian, and Lisa Fitzgerald. 2010. Decriminalisation and stigma. In Taking the Crime Out of Sex Work: New Zealand Sex Workers’ Fight for Decriminalisation. Edited by Gillian Abel, Lisa Fitzgerald, Catherine Healy and Aline Taylor. Bristol: Policy Press, pp. 239–58. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, Farah, Anuroop K. Jhajj, Donna E. Stewart, Madeline Burghardt, and Arlene S. Bierman. 2014. Single item measures of self-rated mental health: A scoping review. BMC Health Services Research 14: e398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allison, Paul. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Alterman, Toni, Sara E. Luckhaupt, James D. Dahlhamer, Brian W. Ward, and Geoffrey M. Calvert. 2013. Job insecurity, work-family imbalance, and hostile work environment: Prevalence data from the 2010 National Health Interview Survey. American Journal of Industrial Medicine 56: 660–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashforth, Blake E., and Glen E. Kreiner. 1999. ‘How can you do it?’ Dirty work and the challenge of constructing a positive identity. The Academy Management Review 24: 413–34. [Google Scholar]

- Bell, Andrew, and Kelvyn Jones. 2015. Explaining fixed effects: Random effects modeling of time-series cross-sectional and panel data. Political Science Research Methods 3: 133–61. [Google Scholar]

- Benach, J., A. Vives, M. Amable, C. Vanroelen, G. Tarafa, and C. Muntaner. 2014. Precarious employment: Understanding an emerging social determinant of health. Annual Review of Public Health 35: 229–53. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Bill McCarthy, and Mikael Jansson. 2015a. Stigma, sex work, and substance use. Sociology of Health and Illness 37: 437–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Bill McCarthy, and Mikael Jansson. 2015b. Occupational stigma and mental health: Discrimination and depression among front-line service workers. Canadian Public Policy 41: S61–S69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Michaela Smith, Mikael S. Jansson, Priscilla Healey, and Douglas Magnuson. 2019. “The prostitution problem”: Claims, evidence, and policy outcomes. Archives of Sexual Behavior 48: 1905–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Michaela Smith, Mikael S. Jansson, Priscilla Healey, and Douglas Magnuson. 2020b. The relative quality of sex work. Work, Employment and Society. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Mikael S. Jansson, Michaela Smith, and Jackson Flagg. 2018. Prostitution stigma and its effect on the working conditions, personal lives, and health of sex workers. The Journal of Sex Research 55: 457–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Nadia Ouellet, and Mikael Jansson. 2016. Unmet health care needs among sex workers in five census metropolitan areas of Canada. Canadian Journal of Public Health 107: e266–e271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Nadia Ouellet, Mikael Jansson, Samantha Magnus, and Michaela Smith. 2017. Would you think about doing sex for money? Structure and agency in deciding to sell sex in Canada. Work, Employment & Society 31: 731–47. [Google Scholar]

- Benoit, Cecilia, Renay Maurice, Gillian Abel, Michaela Smith, Mikael Jansson, Priscilla Healey, and Douglas Magnuson. 2020a. “I dodged the stigma bullet”: Canadian sex workers’ situated responses to occupational stigma. Culture, Health & Sexuality 22: 81–95. [Google Scholar]

- Black, Paula. 2004. The Beauty Industry: Gender, Culture, Pleasure. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bureau of Labor Statistics. 2018. Occupational Employment and Wages, May 2018 39-5012 Hairdressers, Hairstylists, and Cosmetologists. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/oes/2018/may/oes395012.htm (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Casey, Lauren, Bill McCarthy, Rachel Phillips, Cecilia Benoit, Mikael Jansson, Samantha Magnus, Chris Atchison, Bill Reimer, Dan Reist, and Frances M. Shaver. 2017. Managing conflict: An examination of three-way alliances in Canadian escort and massage businesses. In Third Party Sex Work and Pimps in the Age of Anti-Trafficking. Edited by A. Horning and A. Marcus. New York: Springer, pp. 131–49. [Google Scholar]

- Clogg, Clifford C., Eva Petkova, and Adamantios Haritou. 1995. Statistical methods for comparing regression coefficients between models. American Journal of Sociology 100: 1261–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, Rachel Lara. 2010. When it pays to be friendly: Employment relationships and emotional labour in hairstyling. Sociological Review 58: 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, Rachel Lara, Kate Hardy, Teela Sanders, and Carol Wolkowitz. 2013. The body/sex/work nexus: A critical perspective on body work and sex work. In Body/Sex/Work: Intimate, Sexualised and Embodied Work. Edited by Carol Wolkowitz, Rachel Lara Cohen, Teela Sanders and Kate Hardy. New York: Palgrave Macmillian, pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Constable, Nicole. 2009. The commodification of intimacy: Marriage, sex, and reproductive labor. Annual Review of Anthropology 38: 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Araújo, Tânia Maria, and Robert Karasek. 2008. Validity and reliability of the job content questionnaire in formal and informal jobs in Brazil. SJWEH Supplement 6: 52–59. [Google Scholar]

- de Jonge, Jan, Hans Bosma, Richard Peter, and Johannes Siegrist. 2000. Job strain, effort–reward imbalance and employee well-being: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Social Science & Medicine 50: 1317–27. [Google Scholar]

- Deering, Kathleen, Avni Amin, Jean Shoveller, Ariel Nesbitt, Claudia Garcia-Moreno, Putu Duff, Elena Argento, and Kate Shannon. 2014. A systematic review of the correlates of violence against sex workers. American Journal of Public Health 104: e42–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deering, Kathleen, Jean Shoveller, Mark Tyndall, Julio Montaner, and Kate Shannon. 2011. The street cost of drugs and drug use patterns: Relationships with sex work income in an urban Canadian setting. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 118: 430–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Department of Justice Canada. 2014. Technical paper: Bill C-36, Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act. Available online: www.Justice.Gc.Ca/Eng/Rp-Pr/Other-Autre/Protect/P1.Html (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Dwyer, Rachel E. 2013. The care economy? Gender, economic restructuring, and job polarization in the U.S. labor market. American Sociological Review 78: 390–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elo, Irma T. 2009. Social class differentials in health and mortality: Patterns and explanations in comparative perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 35: 553–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Network of Sex Work Projects (NSWP). 2011. Sex Work Is Not Trafficking. Available online: https://www.nswp.org/sites/nswp.org/files/SW%20is%20Not%20Trafficking.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Goffman, Erving. 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. New York: Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Grandey, Alicia A. 2000. Emotion regulation in the workplace: A new way to conceptualize emotional labor. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 5: 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haley-Lock, Anna. 2011. Place-bound jobs at the intersection of policy and management: Comparing employer practices in U.S. and Canadian chain restaurants. American Behavioral Scientist 55: 823–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzenbuehler, Mark L., Anna Bellatorre, Yeonjin Lee, Brian K. Finch, Peter Muennig, and Kevin Fiscella. 2014. Structural stigma and all-cause mortality in sexual minority populations. Social Science & Medicine 103: 33–41. [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Robert M., and John Robert Warren. 1997. Socioeconomic indexes for occupations: A review, update, and critique. Sociological Methodology 27: 177–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckathorn, Douglas D. 2002. Respondent-driven sampling II: Deriving valid population estimates from chain-referral samples of hidden populations. Social Problems 49: 11–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hessels, Jolanda, Cornelius A. Rietveld, and Peter van der Zwan. 2017. Self-employment and work-related stress: The mediating role of job control and job demand. Journal of Business Venturing 32: 178–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, Terrence D., and Christopher Bradley. 2010. The emotional consequences of service work: An ethnographic examination of hair salon workers. Sociological Focus 43: 41–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochschild, Arlie Russell. 1983. The managed heart: The Commercialization of Human Feeling. Berkeley: The University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Horning, Amber, and Anthony Marcus. 2017. Introduction: In search of pimps and other varieties. In Third Party Sex Work and Pimps in the Age of Anti-Trafficking. Edited by Amber Horning and Anthony Marcus. New York: Springer, pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, Everett C. 1962. Good people and dirty work. Social Problems 10: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, Mikael, Bill McCarthy, and Cecilia Benoit. 2013. Interactive Service Workers’ Occupational Health and Safety and Access to Health Services, Methodology Report. Victoria: University of Victoria. Available online: http://web.uvic.ca/~mjansson/pubdoc/ohsmethods.pdf (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Kalleberg, Arne L. 2009. Precarious work, insecure workers: Employment relations in transition. American Sociological Review 74: 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalleberg, Arne L. 2011. Good Jobs, Bad Jobs: The Rise of Polarized and Precarious Employment Systems in the United States, 1970s–2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, American Sociological Association Rose Series in Sociology. [Google Scholar]

- Kalleberg, Arne L., and Steven P. Vallas. 2018. Probing precarious work: Theory, research, and politics. Research in the Sociology of Work 31: 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek, Robert, Chantal Brisson, Norito Kawakami, Irene Houtman, and Paulien Bongers. 1998. The job content questionnaire (JCQ): An instrument for internationally comparative assessments of psychosocial job characteristics. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 3: 322–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Tae Jun, and Olaf von dem Knesebeck. 2015. Is an insecure job better for health than having no job at all? A systematic review of studies investigating the health-related risks of both job insecurity and unemployment. BMC Public Health 15: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krumrei-Mancuso, Elizabeth J. 2017. Sex work and mental health: A study of women in the Netherlands. Archives of Sexual Behavior 46: 1843–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, Cynthia, Gou-Hua Huang, and Susan J. Ashford. 2018. Job insecurity and the changing workplace: Recent developments and the future trends in job insecurity research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5: 335–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Link, Bruce G., and Jo C. Phelan. 2001. Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology 27: 363–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luker, Kristin. 2010. Salsa Dancing into the Social Sciences: Research in an Age of Info-Glut. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Maher, Lisa. 1997. Sexed Work: Gender, Race, and Resistance in a Brooklyn Drug Market. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mak, Winnie W. S., Cecilia Y. M. Poon, Loraine Y. K. Pun, and Shu Fai Cheung. 2007. Meta-analysis of stigma and mental health. Social Science & Medicine 65: 245–61. [Google Scholar]

- Mausner-Dorsch, Hilde, and William W. Eaton. 2000. Psychosocial work environment and depression: Epidemiologic assessment of the demand-control model. American Journal of Public Health 90: 1765–70. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Bill, Cecilia Benoit, and Mikael Jansson. 2014. Sex work: A comparative study. Archives of Sexual Behavior 43: 1379–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, Bill, Cecilia Benoit, Mikeal Jansson, and Kat Kolar. 2012. Regulating sex work: Heterogeneity in legal strategies. Annual Review of Law and Social Science 8: 255–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, Peggy, Diana Worts, Bonnie Fox, and Klaudia Dmitrienko. 2008. Restructuring municipal government: Labor-management relations and worker mental health. The Canadian Review of Sociology 45: 197–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morton, Heather, Carolin Klein, and Boris B. Gorzalka. 2012. Attitudes, beliefs, and knowledge of prostitution and the law in Canada. Canadian Journal of Criminology and Criminal Justice 54: 229–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosack, Katie E., Mary E. Randolph, Julia Dickson-Gomez, Maryann Abbott, Ellen Smith, and Margaret R. Weeks. 2010. Sexual risk-taking among high-risk urban women with and without histories of childhood sexual abuse: Mediating effects of contextual factors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse 19: 43–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakao, Keiko, and Judith Treas. 1994. Updating occupational prestige and socioeconomic scores: How the new measures measure up. Sociological Methodology 24: 1–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolova, Milena. 2019. Switching to self-employment can be good for your health. Journal of Business Venturing 34: 664–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell Davidson, Julia. 2014. Let’s go outside: Bodies, prostitutes, slaves and worker citizens. Citizenship Studies 18: 516–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsthoorn, Martin. 2014. Measuring precarious employment: A proposal for two indicators of precarious employment based on set-theory and tested with Dutch labor market-data. Social Indicators Research 119: 421–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parent, Colette, Chris Bruckert, Patrice Corriveau, Maria Nengeh Mensah, and Louise Toupin. 2013. Sex Work: Rethinking the Job, Respecting the Workers. Translated by Käthe Roth. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, V., J. K. Burns, M. Dhingra, L. Tarver, B. A. Kohrt, and C. Lund. 2018. Income inequality and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of the association and a scoping review of mechanisms. World Psychiatry 17: 76–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paterniti, S., I. Niedhammer, T. Lang, and S. Consoli. 2002. Psychosocial factors at work, personality traits and depressive symptoms: Longitudinal results from the GAZEL study. British Journal of Psychiatry 181: 111–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, Jane. 2015. Sex work and modes of self-employment in the informal economy: Diverse business practices and constraints to effective working. Social Policy and Society 14: 113–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prus, Steven G. 2011. Comparing social determinants of self-rated health across the United States and Canada. Social Science & Medicine 73: 50–69. [Google Scholar]

- Puri, Nitashi, Kate Shannon, Paul Nguyen, and Shira Miriam Goldenberg. 2017. Burden and correlates of mental health diagnoses among sex workers in an urban setting. BMC Women’s Health 17: 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rietveld, Cornelius A., Hans van Kippersluis, and A. Roy Thurik. 2015. Self-employment and health: Barriers or benefits? Health Economics 24: 1302–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, Kristen, and Jane O’Reilly. 2020. “Killing them with kindness”? A study of service employees’ responses to uncivil customers. Journal of Organizational Behavior 41: 797–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, Eva, and Sudhir Alladi Venkatesh. 2008. A “perversion” of choice: Sex work offers just enough in Chicago’s urban ghetto. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography 37: 417–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, Tella. 2005. ‘It’s just acting’: Sex workers’ strategies for capitalizing on sexuality. Gender, Work and Organization 12: 319–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sawicki, Danielle A., Brienna N. Meffert, Kate Read, and Adrienne J. Heinz. 2019. Culturally competent health care for sex workers: An examination of myths that stigmatize sex work and hinder access to care. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 34: 355–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scambler, Graham. 2009. Health-related stigma. Sociology of Health and Illness 31: 441–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherman, Rachel. 2007. Class Acts: Service and Inequality in Luxury Hotels. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqi, Arjumand, Daniyal Zuberi, and Quynh C. Nguyen. 2009. The role of health insurance in explaining immigrant versus non-immigrant disparities in access to health care: Comparing the United States to Canada. Social Science & Medicine 69: 1452–59. [Google Scholar]

- Sliter, Michael, Steve Jex, Katherine Wolford, and Joanne McInnerney. 2010. How rude! Emotional labor as a mediator between customer incivility and employee outcomes. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 15: 468–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Robert, and Maria L. Christou. 2009. Extracting value from their environment: Some observations on pimping and prostitution as entrepreneurship. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 22: 69–84. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Canada. 2018. 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue. No. 98–400-X2016356. Available online: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/global/URLRedirect.cfm?lang = E&ips = 98-400-X2016356 (accessed on 29 November 2020).

- Strega, Susan, Leah Shumka, and Helga Kristin Hallgrímsdóttir. 2020. The “sociological equation”: Intersections between street sex workers’ agency and their theories about their customers. The Journal of Sex Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sullivan, Barbara. 2010. When (some) prostitution is legal: The impact of law reform on sex work in Australia. Journal of Law and Society 37: 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sverke, Magnus, Johnny Hellgren, and Katharina Näswall. 2002. No security: A meta-analysis and review of job insecurity and its consequences. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 7: 242–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Have, Margreet, Saskia van Dorsselaer, and Ron de Graaf. 2015. The association between type and number of adverse working conditions and mental health during a time of economic crisis (2010–2012). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 50: 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Treloar, Carla, Zahra Stardust, Elena Cama, and Jules Kim. 2021. Rethinking the relationship between sex work, mental health and stigma: A qualitative study of sex workers in Australia. Social Science & Medicine 268: 113468. [Google Scholar]

- Umberson, Debra, Robert Crosnoe, and Corinne Reczek. 2010. Social relationships and health behavior across the life course. Annual Review of Sociology 36: 139–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanwesenbeeck, Ine. 2005. Burnout among female indoor sex workers. Archives of Sexual Behavior 34: 627–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Hippel, Paul T. 2007. Regression with missing Ys: An improved strategy for analyzing multiply imputed data. Sociological Methodology 37: 83–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahl, Otto F. 1999. Mental health consumers’ experience of stigma. Schizophrenia Bulletin 25: 467–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. L., A. Lesage, N. Schmitz, and A. Drapeau. 2008. The relationship between work stress and mental disorders in men and women: Findings from a population-based study. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 62: 42–47. [Google Scholar]

- West, Jackie, and Terry Austin. 2002. From work as sex to sex as work: Networks, ‘others’ and occupations in the analysis of work. Gender, Work and Organization 9: 482–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wicks-Lim, Jeannette. 2012. The working poor: A booming demographic. New Labor Forum 21: 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, Nicole, and C. Holmvall. 2013. The development and validation of the incivility from customers scale. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology 18: 310–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Helen W., and Cathy Spatz Widom. 2010. The role of youth problem behaviors in the path from child abuse and neglect to prostitution: A prospective examination. Journal of Research on Adolescence 20: 210–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witz, Anne, Chris Warhurst, and Dennis Nickson. 2003. The labour of aesthetics and the aesthetics of organization. Organization 10: 33–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zelizer, Viviana. 2005. The Purchase of Intimacy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Sex Work | Styling | Hedges’ | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | G | |

| Predictors | ||||||

| Health care use | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 0.30 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 1.93 | 0.27 |

| Wave 2 | 0.31 | 0.18 | 0.21 | 0.20 | 3.41 *** | 0.52 |

| Wave 3 | 0.33 | 0.19 | 0.21 | 0.22 | 3.74 ** | 0.58 |

| Wave 4 | 0.25 | 0.17 | 0.19 | 0.20 | 1.94 | 0.32 |

| Health enhancing behaviors | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 0.72 | 0.45 | 0.76 | 0.43 | 0.68 | 0.09 |

| Wave 2 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 0.67 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.06 |

| Wave 3 | 0.78 | 0.44 | 0.70 | 0.47 | 1.38 | 0.17 |

| Wave 4 | 0.62 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.46 | 1.40 | 0.17 |

| Living with spouse/partner | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 0.22 | 0.42 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 6.35 *** | 0.77 |

| Wave 2 | 0.29 | 0.46 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 4.93 *** | 0.60 |

| Wave 3 | 0.32 | 0.47 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 4.53 *** | 0.53 |

| Wave 4 | 0.34 | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.50 | 3.93 *** | 0.50 |

| Number of children living with respondent | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 0.42 | 0.76 | 0.68 | 0.99 | 2.41 * | 0.29 |

| Wave 2 | 0.44 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 1.02 | 1.81 | 0.21 |

| Wave 3 | 0.48 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 0.99 | 1.36 | 0.21 |

| Wave 4 | 0.49 | 0.95 | 0.65 | 1.09 | 1.35 | 0.15 |

| Substance use 1 | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 8.37 | 8.89 | 5.34 | 7.26 | 2.93 * | 0.38 |

| Wave 2 | 5.90 | 7.48 | 4.93 | 7.02 | 1.06 | 0.13 |

| Wave 3 | 6.54 | 8.31 | 4.75 | 6.82 | 1.87 | 0.24 |

| Wave 4 | 5.52 | 8.06 | 4.78 | 7.16 | 0.77 | 0.10 |

| Substance use 2 | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 4.16 | 6.09 | 0.11 | 0.52 | 6.59 *** | 1.04 |

| Wave 2 | 2.87 | 4.29 | 0.18 | 0.89 | 6.33 *** | 0.96 |

| Wave 3 | 2.79 | 4.59 | 0.19 | 0.97 | 5.59 *** | 0.84 |

| Wave 4 | 2.20 | 3.79 | 0.10 | 0.58 | 5.73 *** | 0.85 |

| Age | 37.35 | 8.93 | 44.32 | 13.05 | 5.24 *** | 1.19 |

| Childhood poverty | 1.80 | 1.03 | 1.52 | 0.78 | 2.46 ** | 0.31 |

| Childhood abuse | 3.44 | 6.36 | 0.55 | 1.36 | 4.80 *** | 0.67 |

| Variable | Sex Work | Styling | Hedges’ | |||

| % | % | Chi Sq | G | |||

| Gender (female) | 86.84 | 82.05 | 1.13 | 0.14 | ||

| Non-heterosexual | 42.47 | 12.33 | 31.50 *** | 0.74 | ||

| Racial minority | 37.17 | 21.29 | 8.18 ** | 0.33 | ||

| Immigrant | 6.90 | 15.92 | 5.12 * | 0.28 | ||

| Less than high school | 46.55 | 14.64 | 33.53 *** | 0.76 | ||

| High school graduate | 33.63 | 58.60 | 16.68 *** | 0.52 | ||

| Some college | 12.07 | 17.20 | 1.38 | 0.14 | ||

| Completed college | 7.75 | 9.55 | 0.27 | 0.07 | ||

| Unemployed | 12.93 | 1.91 | 13.16 *** | 0.45 | ||

| Health insurance | 83.62 | 85.99 | 0.59 | 0.06 | ||

| Variable | Sex Work | Styling | Hedges’ | |||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t | G | |

| Overall mental health | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 3.17 | 1.02 | 3.73 | 0.87 | 7.71 *** | 0.60 |

| Wave 2 | 3.25 | 1.05 | 3.63 | 0.89 | 7.73 *** | 0.40 |

| Wave 3 | 2.99 | 1.07 | 3.62 | 0.97 | 4.80 *** | 0.62 |

| Wave 4 | 3.00 | 1.08 | 3.54 | 0.85 | 4.20 *** | 0.56 |

| Job attributes | ||||||

| Income (logged, in thousands) | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 3231.80 | 2791.53 | 2922.21 | 2181.70 | 0.74 | 0.13 |

| Wave 2 | 2542.14 | 2329.89 | 2798.05 | 2145.11 | 1.84 | 0.12 |

| Wave 3 | 2529.44 | 2555.94 | 2812.95 | 2031.74 | 1.53 | 0.13 |

| Wave 4 | 1919.37 | 1631.73 | 2855.38 | 2181.38 | 3.40 *** | 0.46 |

| Customer hostility | 2.93 | 0.88 | 2.16 | 0.80 | 7.36 *** | 0.92 |

| Stigma | 2.38 | 0.62 | 1.81 | 0.29 | 8.32 *** | 1.24 |

| Insecurity | 2.10 | 0.74 | 1.54 | 0.58 | 6.22 *** | 0.87 |

| Decision latitude | 1.94 | 0.48 | 1.57 | 0.40 | 6.61 *** | 0.85 |

| Psychological demands | 2.78 | 0.44 | 2.85 | 0.40 | 1.41 | 0.17 |

| Percentage Tests of Differences | ||||||

| Variable | Sex Work | Styling | Hedges’ | |||

| % | SD | % | SD | Chi Sq | G | |

| Self-employed | ||||||

| Wave 1 | 0.84 | 0.37 | 0.69 | 0.46 | 7.84 ** | 0.35 |

| Wave 2 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.71 | 0.45 | 0.28 | 0.13 |

| Wave 3 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.66 | 0.45 | 4.71 * | 0.30 |

| Wave 4 | 0.44 | 0.50 | 0.61 | 0.49 | 7.92 ** | 0.34 |

| Variables | Sex Work | Styling | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | b | se | |

| Self-employed (within) | −0.23 | (0.24) | 0.34 * | (0.14) |

| Self-employed (between) | 0.06 | (0.11) | 0.32 ** | (0.12) |

| Income (within) | 0.06 | (0.03) | 0.02 | (0.04) |

| Income (between) | 0.03 | (0.05) | 0.01 | (0.06) |

| Customer hostility | −0.01 | (0.09) | 0.10 | (0.06) |

| Stigma | −0.26 * | (0.13) | −0.38 * | (0.16) |

| Insecurity | −0.25 * | (0.10) | −0.35 *** | (0.10) |

| Little decision latitude | −0.41 * | (0.19) | 0.06 | (0.14) |

| Psychological demands | −0.30 | (0.17) | −0.13 | (0.14) |

| Health enhancing behaviors (within) | −0.02 | (0.10) | −0.08 | (0.07) |

| Health enhancing behaviors (between) | 0.17 | (0.28) | 0.16 | (0.18) |

| Health care use (within) | −0.37 | (0.25) | −0.21 | (0.18) |

| Health care use (between) | −1.23 ** | (0.41) | −1.05 ** | (0.37) |

| Living with spouse/partner (within) | −0.06 | (0.16) | 0.22 | (0.21) |

| Living with spouse/partner (between) | −0.06 | (0.18) | 0.14 | (0.11) |

| Number of children living with (within) | −0.01 | (0.08) | −0.02 | (0.06) |

| Number of children living with (between) | −0.06 | (0.11) | −0.02 | (0.05) |

| Substance use 1 (within) | −0.02 ** | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.01) |

| Substance use 1 (between) | −0.00 | (0.01) | −0.01 | (0.01) |

| Substance use 2 (within) | −0.03 | (0.01) | −0.04 | (0.05) |

| Substance use 2 (between) | 0.01 | (0.02) | 0.02 | (0.10) |

| Age | −0.01 | (0.01) | 0.00 | (0.00) |

| Gender (1 = female) | −0.10 | (0.20) | −0.16 | (0.13) |

| Sexual minority | 0.08 | (0.16) | 0.06 | (0.16) |

| Racial minority | 0.07 | (0.15) | 0.23 | (0.13) |

| Immigrant | 0.02 | (0.31) | −0.14 | (0.15) |

| Non high school graduate | 0.12 | (0.15) | −0.08 | (0.15) |

| Some college | 0.62 * | (0.25) | 0.07 | (0.14) |

| College graduate | 0.45 | (0.28) | 0.23 | (0.17) |

| Ever unemployed (W1 to W4) | −0.15 | (0.21) | −0.50 | (0.37) |

| Childhood economic insecurity | −0.14 * | (0.06) | −0.08 | (0.07) |

| Childhood abuse | −0.00 | (0.01) | −0.04 | (0.04) |

| Access to health care | 0.49 * | (0.23) | 0.25 | (0.16) |

| Country (USA = 1) | 0.68 ** | (0.21) | −0.11 | (0.12) |

| Wave 2 dummy | −0.08 | (0.10) | −0.13 | (0.07) |

| Wave 3 dummy | 0.20 | (0.11) | −0.12 | (0.08) |

| Wave 4 dummy | 0.11 | (0.12) | −0.19 * | (0.08) |

| Constant | 5.84 *** | (0.91) | 4.89 *** | (0.77) |

| Number of observations/groups | 347/93 | 593/155 | ||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

McCarthy, B.; Jansson, M.; Benoit, C. Job Attributes and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of Sex Work and Hairstyling. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020035

McCarthy B, Jansson M, Benoit C. Job Attributes and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of Sex Work and Hairstyling. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleMcCarthy, Bill, Mikael Jansson, and Cecilia Benoit. 2021. "Job Attributes and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of Sex Work and Hairstyling" Social Sciences 10, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020035

APA StyleMcCarthy, B., Jansson, M., & Benoit, C. (2021). Job Attributes and Mental Health: A Comparative Study of Sex Work and Hairstyling. Social Sciences, 10(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10020035