Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Principles of Neoliberalism

Neoliberalism is […] a theory of political economic practices that proposes that human well-being can best be advanced by liberating individual entrepreneurial freedoms and skills within an institutional framework characterized by strong private property rights, free markets, and free trade. The role of the state is to create and preserve an institutional framework appropriate to such practices.

3. Growth of Neoliberalism in Canada

Neoliberalism in the Federal Context

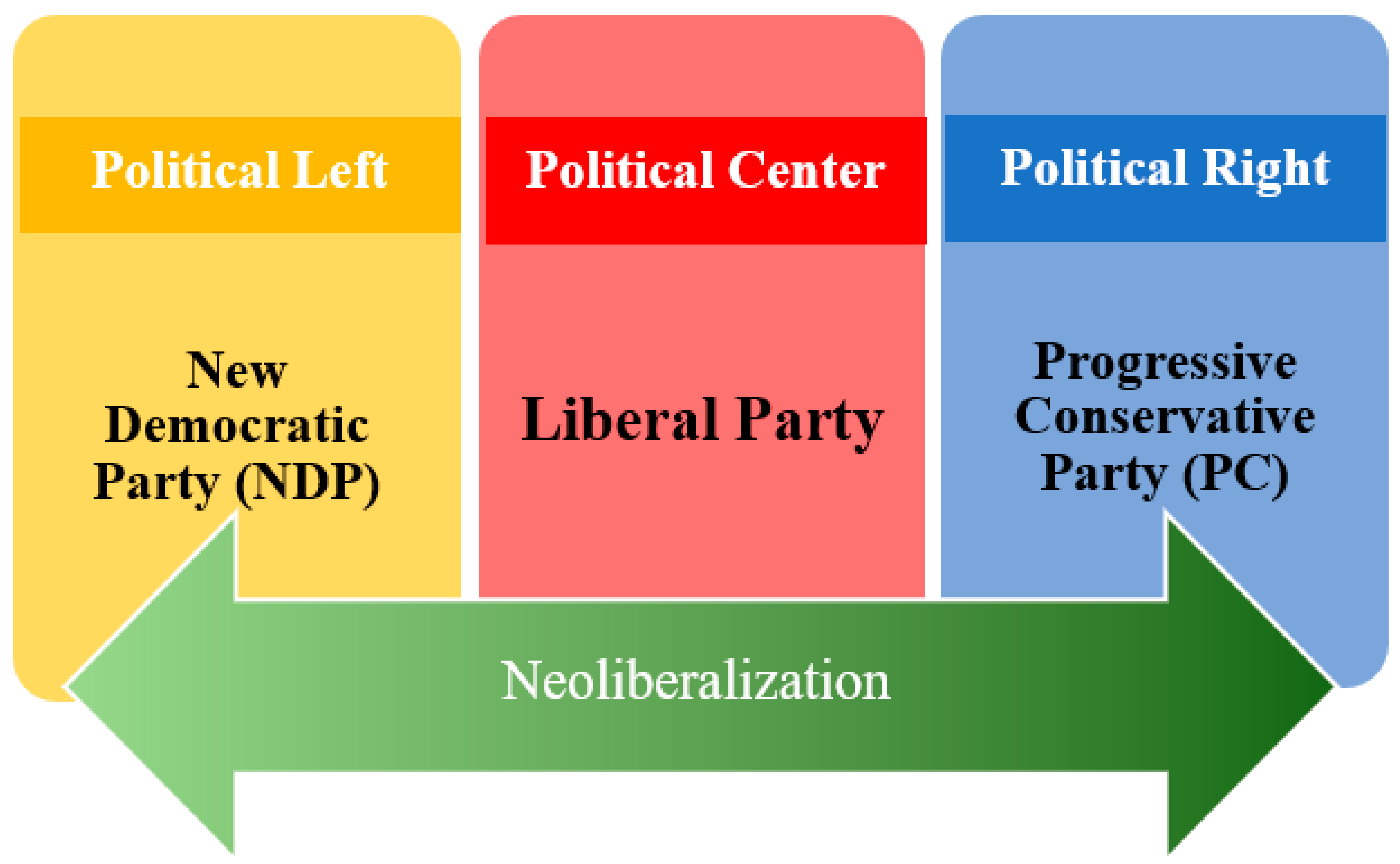

4. Neoliberalism and Ontario’s Provincial Government

4.1. Post-War Ontario and the Recession: 1943 to 1985

4.2. Beginnings of Neoliberal Thought: 1985 to 1995

4.3. Aggressive Neoliberalization in Ontario: 1995 to 2003

4.4. Neoliberalism and the Illusion of Social Progression: 2003 to 2020

5. The Origins of Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy

5.1. Addressing Poverty in Neoliberal Times

5.2. Mobilizing Change through Grassroots Movements

5.3. Drafting the Poverty Reduction Strategy: Consulting, Designing, and Legislating

6. Poverty Reduction in Present-Day Ontario: Reverting to Aggressive Neoliberal Policies

7. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | It should be noted that the critical theory paradigm is not a monolithic analytical lens,. There exist multiple branches, traditions, and iterations of critical theory informed by various schools of thought. Critical theorists draw from the eclectic works of diverse scholars including Karl Marx, neo-Marxist theorists of the Frankfurt School such as Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno, Michel Foucault, Immanuel Kant, Antonio Gramsci, Stuart Hall, Paulo Freire, Franz Fanon, Simone de Beauvoir, Patricia Hill Collins, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, amongst many others (see Fuchs 2020; Kellner 1990; Kincheloe et al. 2018). |

| 2 | Hegemony, in the Gramscian sense, is power that operates through the consent of the governed. In other words, hegemonic values are perpetuated and reinforced through social interactions, relationships, structures, and institutions, rather than through coercion or force, which ultimately helps establish hierarchies of domination within society (see Thomas 2012; Garlitz and Zompetti 2021). Hegemonic ideas also ebb-and-flow over time, according to historical moments and contexts (Garlitz and Zompetti 2021). |

| 3 | Although neoliberalism has been described here in very clear-cut and absolute terms, it is an ideology that is much more complex, dynamic, and variegated than explicated within the current discussion (Fletcher 2019). Neoliberal thought can manifest differently within diverse contexts such that specific principles are emphasized in certain spaces and minimized in others. For the purpose of this paper, I approach the concept of neoliberalism from the angle of Marxist-derived critical theory; thus, framing the direction of the analysis presented and the definitions adopted within this paper in kind. It should be noted that the multifaceted nature of neoliberalism has been widely discussed and extensively debated elsewhere within the literature (see Brenner et al. 2010; Castree 2010; Ferguson 2010; Jessop 2019; Springer 2012; Venugopal 2015). An in-depth and comprehensive exploration of neoliberalism’s multiple definitions and conceptualizations, which are all firmly rooted within particular paradigmatic traditions and theoretical frameworks, falls beyond the scope of this paper’s focus. |

| 4 | Targeted social programs are provided on a means-tested basis, whereas universal programs are accessible to everyone irrespective of a person’s income or assets (P. Evans 1996). |

| 5 | Transfer payments redistribute tax revenues to provincial governments and individuals vis-à-vis direct cash payments offered on either a conditional or unconditional basis. They are used to fund social services and provide financial support. |

| 6 | Social planning councils are a network of nonprofit community-based organizations that are concerned with social policy issues, social planning, advocacy, and research. They run on a mandate of social justice, community development, and community mobilization. The establishment of these councils was spearheaded by the Canadian Council of Social Development (CCSD) in the 1970s. They can now be found across Canada, with a significant concentration in Ontario. The main network in Ontario is called the Social Planning Network of Ontario (SPNO) and has played a key role in gauging anti-poverty initiatives (Maxwell 2009). All social planning councils are collaborative and interactive, sharing ideas through conferences and meetings (Canadian Council on Social Development 2013). |

| 7 | Between 1966 and 1995, the federal government had two mechanisms of sharing tax revenues amongst the provinces. The first method was through Established Programs Financing (EPF) which transferred predetermined block payments to each province in order to support healthcare and education. The EPF was distributed equally to each province on a per capita basis. The second method was through the Canada Assistance Plan (CAP) which provided funding based on a cost-sharing model where the federal government equally matched the amount spent by each province for programs such as social assistance, social housing, child welfare, civil legal aid, and community programs such as child care, women’s counseling and shelter services. In 1990, under Mulroney’s neoliberal agenda, a limit was implemented on the CAP for Ontario, Alberta, and British Columbia. In 1995 the CAP was completely replaced with Canada Health and Social Transfer (CHST). The CHST eliminated the 50–50 matching of funds that characterized the CAP, instead providing a per capita block payment which was generally lower than what the CAP provided. The CHST was used to fund Medicare, post-secondary education, welfare and social services (Department of Finance Canada 2014; Maxwell 2009). |

| 8 | Historically, during their 42 years in power, the Progressive Conservatives had operated from the political center. Political commentators called their approach ‘Red Toryism’ because it was characterized by policies that took a more liberal or mildly socialist stance on certain fiscal and social issues. In other words, ‘Red Tories’ are less conservative than their ‘Blue Tory’ counterparts who are staunch believers in free enterprise, tax reduction and corporate welfare. Mike Harris’ government falls into the latter category of Blue Tory (Fanelli and Thomas 2011). |

| 9 | A single individual under Harris’ reformed social assistance plan received $520 per month, out of which a maximum of $325 was allocated towards shelter (including rent and utilities). The remaining $195 was to be used for personal expenses such as food, clothing, and other items for survival. The average rent during this time (within urban dwellings like Toronto) was much higher than was allocated by the province (Esmonde 2002). |

| 10 | Individuals who wash vehicle windshields in exchange for change, found mainly on busy streets in urban centers (Esmonde 2002). |

| 11 | The 25in5 network recommended raising the limit for personal assets to $5000 for single people and $10,000 for families and people with disabilities (Hudson and Graefe 2012). |

| 12 | Roundtable discussions were convened by Deb Matthews who was, at that time, Chair of the Cabinet Committee of Poverty reduction and the Minister of Child and Youth Services (Clutterbuck 2008; Government of Ontario 2008). |

| 13 | On 13 December 2002, Quebec became the first province to introduce legislation that focused on combatting poverty and social exclusion (Mendell 2009). They were also the first to establish a provincial poverty reduction plan in all of Canada, which was released in August 2002, entitled The Will to Act, The Strength to Succeed. National Strategy to Combat Poverty and Social Exclusion (Mendell 2009). One of the key strengths of Quebec’s plan was its multidimensional approach to poverty, taking into account the dimensions of social exclusion. Quebec’s provincial government also developed a 15 member advisory committee on poverty reduction/social exclusion and established a research center dedicated to evaluating the progress of the strategy as well as making innovations in poverty indicators and measures (Mendell 2009). Quebec’s policy inspired other provinces to follow suit, including Newfoundland and Labrador and Ontario (Mendell 2009). |

| 14 | The geographical areas for the pilot study were determined based on urban/ rural location, demographics, economic need and access to social services. Areas chosen include Hamilton, Brantford, Brant County, Lindsay, and Thunderbay and surrounding area (Government of Ontario 2017). |

| 15 | Inclusive of age, race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, sexual orientation, ability, geographical location, educational attainment or employment status. |

References

- Albert, Jim, and Bill Kirwin. 2006. Social and welfare services. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/social-and-welfare-services (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Armstrong, Tim. 2018. Premier Ford’s Troublesome Track Record. Toronto Star. December 17. Available online: https://www.thestar.com/opinion/contributors/2018/12/17/premier-fords-troublesome-track-record.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Association of Local Public Health Agencies (ALPHA). 2018. Re: Alpha Resolution AlS-4, Public Health Support for a Basic Income Guarantee [Open Letter]. August 2. Available online: https://www.rcdhu.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/04.-Correspondence.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Azmanova, Albena. 2020. Capitalism on Edge: How Fighting Precarity Can Achieve Radical Change without Crisis or Utopia. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, Pedro, and Colette Murphy. 2011. Foundations for Social Change: Reflections on Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy. Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale 65/66: 16–30. Available online: https://crsp.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/crsp/article/view/35192 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Baxter, Pamela, and Susan Jack. 2008. Qualitative Case Study Methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report 13: 544–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beattie, Samantha. 2018. The Winners and Losers of Ontario Premier Doug Ford’s Spending Cuts So Far. Huffpost Canada. December 21. Available online: https://www.huffingtonpost.ca/2018/12/21/doug-ford-cuts_a_23624751/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Bierman, Arlene S., Farah Ahmad, and Farah N. Mawani. 2009. Gender, migration and health. In Racialized Migrant Women in Canada: Essays on Health, Violence and Equity. Edited by Vijay Agnew. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 98–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnar, John. 2010. Timeline: Ontario Eliminates Special Diet Allowance for Social Assistance Recipients. Rabble. March 28. Available online: http://rabble.ca/blogs/bloggers/johnbon/2010/03/timeline-ontario-eliminates-special-diet-allowance-social-assistance (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Brenner, Neil, Jamie Peck, and Nik Theodore. 2010. Variegated neoliberalization: Geographies, modalities, pathways. Global Networks 10: 182–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canadian AIDS Society. 2018. Support Life-Saving Supervised Consumption and Overdose Prevention Sites: Open Letter to Premier Doug Ford and Health Minister Christine Elliott [Open Letter]. August 30. Available online: https://www.cdnaids.ca/wp-content/uploads/Open-Letter-re-SCS-and-OPS_Ontario_FINAL.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Canadian Council on Social Development. 2013. Social Development by Design. Available online: http://www.ccsd.ca/images/docs/CCSD_New_Approach.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Castree, Noel. 2010. Neoliberalism and the biophysical environment: A synthesis and evaluation of the research. Environment and Society 1: 5–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapell, Rosalie. 2006. Social Welfare in Canadian Society, 3rd ed. Toronto: Thomson Nelson. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, John. 2001. A Short History of OCAP. Available online: http://www.ocap.ca/archive/short_history_of_ocap.html (accessed on 27 November 2015).

- Clutterbuck, Peter. 2008. Summary Report: Ontario Poverty Reduction Strategy Consultations (March to August 2008). Poverty Watch Ontario. Available online: https://povertywatchontario.ca/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/downloads/Summary-Report-Ontario-Poverty-Reduction-Strategy-Consultations-Sept8-2008.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Collier, Roger. 2018. Decisions by new Ontario government worry science and health care communities. Canadian Medical Association Journal 190: E917–E918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coulter, Kendra. 2009. Deep neoliberal integration: The production of third way politics in Ontario. Studies in Political Economy 83: 191–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denette, Nathan. 2013. Kathleen Wynne Sworn in as Ontario’s First Female Premier, Unveils Cabinet. National Post. February 11. Available online: https://nationalpost.com/news/politics/kathleen-wynne-sworn-in-as-ontarios-first-female-premier-unveils-cabinet (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Denzin, Norman K., and Yvonna S. Lincoln. 2011. Introduction: The Discipline and Practice of Qualitative Research. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 4th ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc, pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Finance Canada. 2014. History of Health and Social Transfers. Government of Canada. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/department-finance/programs/federal-transfers/history-health-social-transfers.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Dimand, Robert W. 2019. Keynesianism in Canada. In The Elgar Companion to John Maynard Keynes. Edited by Robert W. Dimand and Harald Hagemann. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing Inc., pp. 588–94. [Google Scholar]

- Esmonde, Jackie. 2002. Criminalizing poverty: The criminal law power and the safe streets act. Journal of Law and Social Policy 17: 63–86. Available online: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/jlsp/vol17/iss1/4 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Esping-Andersen, Gøsta, ed. 1990. The Three Political Economies of the Welfare State and De-Commodification in Social Policy. In The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Bryan. 2007. Treading water: Four years of Ontario’s liberals. The Socialist Project E-Bulletin 59: 1–6. Available online: http://www.socialistproject.ca/bullet/bullet059.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Evans, Patricia. 1996. Eroding Canadian social welfare: The Mulroney legacy 1984–1993. In Social Fabric or Patchwork Quilt. Edited by Raymond B. Blake and Jeffery Keshen. Peterborough: Broadview Press, pp. 263–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fanelli, Carlo, and Mark P. Thomas. 2011. Austerity, competitiveness and neoliberalism redux: Ontario responds to the great recession. Socialist Studies/Études Socialistes 7: 141–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ferguson, James. 2010. The uses of neoliberalism. Antipode 41: 166–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernando, Shanti, and Benjamin Earle. 2011. Linking Poverty Reduction and Economic Recovery: Supporting community responses to austerity in Ontario. Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale 65/66: 31–44. Available online: https://crsp.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/crsp/article/view/35197 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Fletcher, Robert. 2019. On exactitude in social science: A multidimensional proposal for investigating articulated neoliberalization and its ‘alternatives’. Ephemera: Theory and Politics in Organization 19: 537–64. Available online: http://www.ephemerajournal.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/contribution/19-3fletcher_0.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Fuchs, Christian. 2020. Towards a critical theory of communication as renewal and update of Marxist humanism in the age of digital capitalism. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour 50: 335–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garlitz, Dustin, and Joseph Zompetti. 2021. Critical theory as Post-Marxism: The Frankfurt School and beyond. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giroux, Henry A. 2004. The Terror of Neoliberalism: Authoritarianism and the Eclipse of Democracy. Boulder: Paradigm. [Google Scholar]

- Government of Ontario. 2008. Breaking the Cycle: Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy (2009–2013). Ontario Cabinet Committee on Poverty Reduction. Available online: www.children.gov.on.ca/htdocs/English/documents/growingstronger/Poverty_Report_EN.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Government of Ontario. 2014. Realizing Our Potential: Ontario’s Poverty Reduction Strategy (2014–2019). Ontario Ministry Responsible for the Poverty Reduction Strategy. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/realizing-our-potential-ontarios-poverty-reduction-strategy-2014-2019 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Government of Ontario. 2017. Backgrounder: Ontario’s Basic Income Pilot. Ministry of Children, Community and Social Services. Available online: https://news.ontario.ca/mcys/en/2017/4/ontarios-basic-income-pilot.html (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Government of Ontario. 2018. Poverty Reduction in Ontario. September 27. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/poverty-reduction-in-ontario (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Government of Ontario. 2020. Building a Strong Foundation for Success: Reducing Poverty in Ontario (2020–2025). December 16. Available online: https://www.ontario.ca/page/building-strong-foundation-success-reducing-poverty-ontario-2020-2025#section-7 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Grinspun, Doris. 2018. Re: Reconsider Your Decision to Cut/Damage/Compromise Ontario’s Social Safety Net [Open Letter]. Registered Nurses’ Association of Ontario (RNAO). September 7. Available online: https://rnao.ca/sites/rnao-ca/files/RNAO_Letter_to_Minister_MacLeod_-_re_Ontario_s_social_safety_net_-_Sept_7_2018.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Guest, Dennis. 2006. Social Security. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online: http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/social-security/ (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Habibov, Nazim, and Lida Fan. 2007. Poverty reduction and social security in Canada from Mixed to Neo-Liberal welfare regimes: Estimation from household surveys. Journal of Policy Practice 6: 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harvey, David. 2005. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Carol-Anne, and Peter Graefe. 2012. The Toronto Origins of Ontario’s 2008 Poverty Reduction Strategy: Mobilizing Multiple Channels of Influence for Progressive Social Policy Change. Canadian Review of Social Policy/Revue Canadienne de Politique Sociale 65/66: 1–15. Available online: https://crsp.journals.yorku.ca/index.php/crsp/article/view/35221 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Jessop, Bob. 2019. Primacy of the Economy, Primacy of the Political: Critical Theory of Neoliberalism. In Handbuch Kritische Theorie. Edited by Uwe H. Bittlingmayer, Alex Demirović and Tatjana Freytag. Wiesbaden: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazemipur, Abdolmohammad, and Shiva S. Halli. 2001. The changing colour of poverty in Canada. Canadian Review of Sociology/Revue Canadienne de Sociologie 38: 217–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kellner, Douglas. 1990. Critical theory and the crisis of social theory. Sociological Perspectives 33: 11–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kincheloe, Joe L., Peter McLaren, Shirley R. Steinberg, and Lilia D. Monzó. 2018. Critical Pedagogy and Qualitative Research: Advancing the Bricolage. In The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 5th ed. Edited by Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, Inc., pp. 235–60. [Google Scholar]

- Kivisto, Peter. 2021. The social question in neoliberal times. Ethnic and Racial Studies 44: 1368–1375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozolanka, Kirsten. 2010. Unworthy Citizens, Poverty, and the Media: A Study in Marginalized Voices and Oppositional Communication. Studies in Political Economy 86: 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larner, Wendy. 2000. Neoliberalism: Policy, ideology, governmentality. Studies in Political Economy 63: 5–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legislative Assembly of Ontario. 2009. Bill C-152: An Act Respecting a Long-Term Strategy to Reduce Poverty in Ontario, 1st Reading 25 February 2009, 39th Parliament, 1st Session, Assented to 6 May 2009. Available online: https://www.ola.org/en/legislative-business/bills/parliament-39/session-1/bill-152 (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Mahon, Rianne. 2008. Varieties of liberalism: Canadian social policy from the ‘golden age’ to the present. Social Policy and Administration 42: 342–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, Glynis. 2009. Poverty reduction policies and programs. In Poverty in Ontario–Failed promise and the Renewal of Hope: Ontario. Ottawa: Canadian Council on Social Development. Available online: https://www.spno.ca/images/pdf/Poverty-in-Ontario-Report.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- McBride, Stephen. 1996. The continuing crisis of social democracy: Ontario’s social contract in perspective. Studies in Political Economy 50: 65–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McBride, Stephen. 2005. Paradigm Shift: Globalization and the Canadian State, 2nd ed. Halifax: Fernwood Books. [Google Scholar]

- Mendell, Anika. 2009. Comprehensive Policies to Combat Poverty Across Canada by Province: Preliminary Document for Discussion. National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy. Available online: http://www.ncchpp.ca/docs/ComprehensivePolicies_En_Sept09.pdf (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Parliament of Canada. 2016a. Prime Ministers of Canada: Biographical Information. Available online: http://www.lop.parl.gc.ca/ParlInfo/compilations/federalgovernment/primeministers/biographical.aspx (accessed on 25 November 2015).

- Parliament of Canada. 2016b. Ontario: Premiers. Available online: http://www.lop.parl.gc.ca/ParlInfo/Files/Province.aspx?Item=01af46d5-b145-4531-84b7ea39742bd2b6andLanguage=EandMenuID=Compilations.ProvinceTerritory.aspx.MenuandSection=Premiers (accessed on 25 November 2015).

- Raddon, Mary B. 2012. Financial fitness: The political and cultural economy of finance. In Power and Everyday Practices. Edited by Deborah Brock, Rebecca Raby and Mark P. Thomas. Toronto: Nelson Education, pp. 223–45. [Google Scholar]

- Raphael, Dennis. 2011. Poverty in Canada: Implications for Health and Quality of Life, 2nd ed. Toronto: Canadian Scholar’s Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, David P., and Clarence Lochhead. 2007. Poverty. The Canadian Encyclopedia. Available online: https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/poverty (accessed on 18 December 2021).

- Sarlo, Chris, and Suzanne Walters. 2001. A New Study Says Poverty in Canada Continued to Be Overstated. The Fraser Institute. Available online: http://oldfraser.lexi.net/media/media_releases/2001/20010723.html (accessed on 15 September 2015).

- Schram, Sanford F. 2019. Neoliberal relations of poverty and the welfare state. In The Routledge Handbook of Critical Social Work. Edited by Stephen E. Webb. New York: Routledge, pp. 15–23. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma, Raghubar D. 2012. Issues in Canada: Poverty in Canada. Don Mills: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Springer, Simon. 2012. Neoliberalism as discourse: Between Foucauldian political economy and Marxian poststructuralism. Critical Discourse Studies 9: 133–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steger, Manfred B., and Ravi K. Roy. 2010. Neoliberalism: A Very Short Introduction, 1st ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanguay, Brian A. 1997. “Not in Ontario!” From the Social Contract to the Common Sense Revolution. In Revolution at Queen’s Park: Essays on Governing Ontario. Edited by Sid Noel. Toronto: James Lorimer and Company, pp. 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, Mark P. 2012. Class, state and power: Unpacking social relations in contemporary capitalism. In Power and Everyday Practices. Edited by Deborah Brock, Rebecca Raby and Mark P. Thomas. Toronto: Nelson Education, pp. 110–32. [Google Scholar]

- Venugopal, Rajesh. 2015. Neoliberalism as concept. Economy and Society 44: 165–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, Randall. 1999. Ontario since 1985: A Contemporary History. Toronto: EastEnd Books. [Google Scholar]

- Yin, Robert K. 2003. Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

| Prime Minister | Political Party in Power | Time Period | Political Ideology and Impact on Social Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Louis St. Laurent | Liberal | 1948–1957 | Post-World War II Period

|

| John Diefenbaker | Progressive Conservative | 1957–1963 | |

| Lester B. Pearson | Liberal | 1963–1968 | |

| Pierre Elliott Trudeau | Liberal | 1968–1979 | |

| Joe Clark | Progressive Conservative | 1979–1980 | Transition Phase

|

| Pierre Elliott Trudeau | Liberal | 1980–1984 | |

| John Turner | Liberal | 1984 | |

| Brian Mulroney | Progressive Conservative | 1984–1993 | Neoliberal Period

|

| Kim Campbell | Progressive Conservative | 1993 | |

| Jean Chrétien | Liberal | 1993–2003 | |

| Paul Martin | Liberal | 2003–2006 | |

| Stephen Harper | Conservative | 2006–2015 | |

| Justin Trudeau | Liberal | 2015–present |

| Ontario’s Premier | Political Party in Power | Time Period | Political Ideology and Impact on Social Policy |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. George Drew 2. Thomas Kennedy 3. Leslie Frost 4. John Robarts 5. Bill Davis 6. Frank Miller | Progressive Conservative | 1943–1985 | Post-World War II period

|

| David Peterson | Liberal | 1985–1990 | Neoliberal period begins Period of subtle neoliberal integration |

| Bob Rae | New Democratic Party | 1990–1995 | |

| Mike Harris | Progressive Conservative | 1995–2002 | Period of aggressive neoliberal integration |

| Ernie Eves | Progressive Conservative | 2002–2003 | |

| Dalton McGuinty | Liberal | 2003–2013 | Period of subtle neoliberal integration |

| Kathleen Wynn | Liberal | 2013–2018 | |

| Doug Ford | Progressive Conservative | 2018–present | Period of aggressive neoliberal integration |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gill, J.K. Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120485

Gill JK. Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(12):485. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120485

Chicago/Turabian StyleGill, Jessica K. 2021. "Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis" Social Sciences 10, no. 12: 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120485

APA StyleGill, J. K. (2021). Unpacking the Role of Neoliberalism on the Politics of Poverty Reduction Policies in Ontario, Canada: A Descriptive Case Study and Critical Analysis. Social Sciences, 10(12), 485. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120485