How Gender Is Recognised in Economic and Education Policy Programmes and Initiatives: An Analysis of Nigerian State Policy Discourse

Abstract

1. Introduction

Analysing Public Policy and Gender

2. The Nigerian Context for Gender in Policies and in Economy

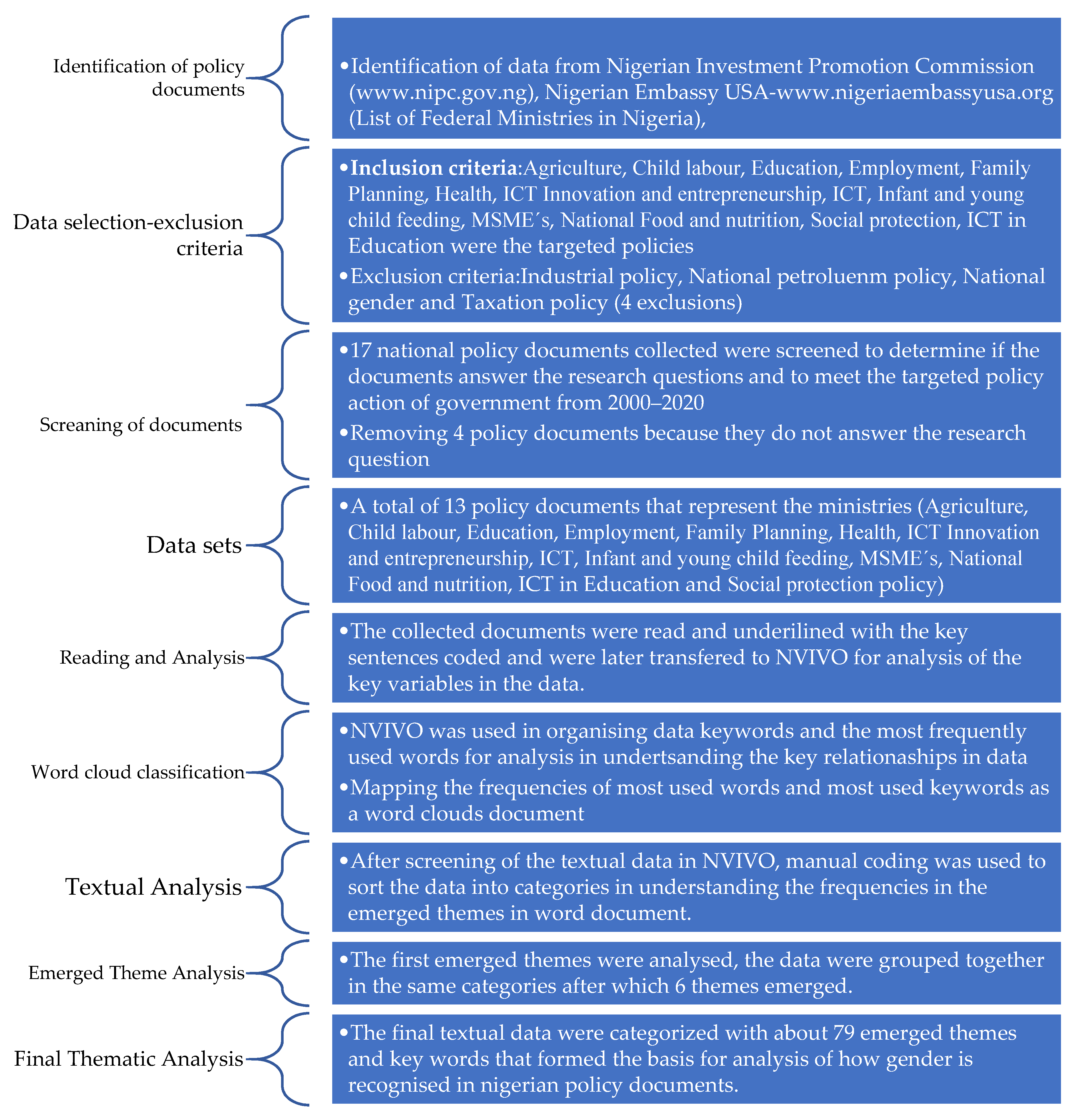

3. Methodology: Research Design, Materials, and Analysis

Data Analysis

4. Results: Gendered Recognition in Policy Document

4.1. Education

4.2. Gender

4.3. Access

4.4. Discrimination

4.5. Implementation

4.6. Cultural

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Documents on the Public Policy Programmes | Exclusion | Year | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | National food and nutrition policy | 2001 | |

| 2 | ICT Innovation and entrepreneurship policy | 2001–2025 | |

| 3 | Infant and young child feeding policy | 2008 | |

| 4 | National Gender Policy | Excluded | 2008–2013 |

| 5 | Taxation Policy | Excluded | 2012 |

| 6 | ICT policy | 2012 | |

| 7 | Child labour policy | 2013 | |

| 8 | Nigeria Industrial Revolution Plan | Excluded | 2014 |

| 9 | Family Planning policy | 2014 | |

| 10 | MSME’s policy | 2015–2025 | |

| 11 | Agriculture policy | 2016–2020 | |

| 12 | Health policy | 2016–2020 | |

| 13 | The National Petroleum Policy | Excluded | 2017 |

| 14 | Employment policy | 2017 | |

| 15 | Social protection policy | 2017 | |

| 16 | Educational policy | 2018–2022 | |

| 17 | ICT in Education policy | 2019 |

| Themes | Gendered Recognition Coded and Categorised Themes |

|---|---|

| Education (18) | 12.7 million out-of-school children 60% percent of girls are not in school Females account for nearly 60 per cent of the country’s illiterate population Girls of school age constitute 60 per cent of population High numbers of absenteeism/children not in school in North Inadequate educational funding Low Boy enrolment in STEM Low female enrolment and retention in ST&I disciplines Low female enrolment in STEM and TVET Male and female education imbalance No equitable balance of male and female teachers Out-of-school boys Socio-cultural barriers that impede female participation in basic education There are issues of education quality, poor education facilities There are out of schoolboys There is undoubtedly neglect of girls and women’s education Women exclusion from technological innovations Women experience sexual harassment and other social vices in school |

| Gender (14) | Gender advocacy needed Gender advocacy needed at federal, state, and local government levels on contraceptive usage Gender education imbalance Gender education imbalance Gender imbalance male and female teachers Gender inequalities in primary and secondary education Gender mainstreaming are needed for girl’s child education to promote gender mainstreaming in ST&I Gender mainstreaming in all policy areas Gender mainstreaming in all policy areas Lack of evaluation mechanism that will effectively track and report child labour situations Lack of gender mainstreaming policy and programmes Lack of Gender-sensitive and programming activities Lack of promotion of consistent and effective gender-responsive programs for male and female There is need to mainstream women in ST&I and provide more incentives to increase women’s participation in STI |

| Access (14) | Inadequate maternity and, health-care protection against women Lack of access for women and girls to ST&I.Lack of access to basic education for girls. Lack of access to knowledge on contraceptives Limited access to finance for women Only 15 percent of married women have access to contraceptive & unmet need of 36% Partner opposition on the use of contraceptives, Fear of side effects of contraceptives, and religious prohibitions on the use of contraceptives Women and youth lack access to financial institutional support Lack of mechanization serves as a disincentive to women in agriculture Women lack access to agriculture inputs Women lack access to finance women lack access to information Women lack access to land |

| Discrimination (13) | Discrimination Against Women Discrimination against women in land holding Discrimination in access to education for girls Discrimination in access to education for girls Discriminations in employment Gender bias in land ownership Marginalisation in access to resources, finance, assets, training, Marginalisation in access to technology and information Socio-cultural discrimination There is discrimination against women workers in recruitment, remuneration, promotion, and training. There is gender discrimination in land access to women There is marginalisation of women in the economy Women and other groups are marginalized |

| Implementation (13) | Developing proper implementation between all stake holders Lack of collaboration between Government and NGOs on implementation of women’s programmes Lack of collaboration between implementation agencies and stakeholders on child labour issues Lack of coordination for implementation of national programmes on child labour Lack of framework to encourage and increase women’s employment in ST&I sectors Lack of legal framework that protects intended beneficiaries including children through inheritance rights, birth registration, childcare services, and breast feeding. Lack of political and institutional participation on framework to promote women’s ST&I. Non-implementation of national teachers’ policy Poor enforcement of gender-based policies and institutional bias There are barriers to effective implementation of child labour policy and programmes There are challenges with the implementation principles in eliminating of all forms of discrimination against women Weak implementation of policies to ensure inclusion of women Weak legal framework to protect and promote the welfare of women and children |

| Cultural (7) | Harmful traditional practices against women Socio-cultural barriers against women Socio-cultural barriers impede female participation in basic education Socio economic factors; economic demand, poverty, child labour, gender unfriendly educational facility Distance from school and limited job opportunities and early marriage against girl-child education. Socio-cultural practices against women as regards inherited lands Socio-cultural, financial, or legislative encumbrances hindering women from fair participation in agriculture |

References

- Abdul, Mariam Marwa, Olayinka Adeleke, Olajumoke Adeyeye, Adenike Babalola, Emilia Eyo, Maryam Tauhida Ibrahim, and Martha Onose Monica Voke-Ighorodje. 2011. Analysis of the History, Organisations and Challenges of Feminism in Nigeria. October 2011 Published by Nigerian Group, Nawey.Net. Available online: http://www.nawey.net/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/05/Feminism-in-Nigeria.pdf (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Acs, Zoltan J., and Laszlo Szerb. 2007. Entrepreneurship, Economic Growth and Public Policy. Small Business Economics 28: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aderemi, Helen. 2019. Chapter 4 Rethinking Gender Roles towards Promotion of Socioeconomic Advancement: Evolution of entrepreneurship in Nigeria. In Through the Gender Lens: A Century of Social and Political Development in Nigeria. Edited by Funmi Soetan and Bola Akanji. A Book Review. Lanham: Lexington Books, vol. 34, pp. 83–84. [Google Scholar]

- Afolabi, Adeoye. 2015. The Effect of Entrepreneurship on Economic Growth and Development in Nigeria. International Journal of Development and Economic Sustainability 3: 49–65. [Google Scholar]

- Ahl, Helene, and Teresa Nelson. 2014. How Policy Positions Women Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Analysis of State Discourse in Sweden and the United States. Journal of Business Venturing 30: 273–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, Iyanda Kamoru, and Bello Sanusi Dantata. 2016. Problems and Challenges of Policy Implementation for National Development. Research on Humanities and Social Sciences 6: 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ajala, Taiwo. 2017. Gender Discrimination in Land Ownership and the Alleviation of Women’s Poverty in Nigeria: A Call for New Equities. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 17: 51–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinyemi, Folashade O., and Oluwabunmi O. Adejumo. 2018. Government Policies and Entrepreneurship Phases in Emerging Economies: Nigeria and South Africa. Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 8: 2–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amanda, Holpuch. 2018. Stolen Daughters-What Happened after #BringBackOurGirls. The Guardian Documentary 22nd October 2018. New York: Guardian US. [Google Scholar]

- Arshed, Norin, Sara Carter, and Colin Mason. 2014. The Ineffectiveness of Entrepreneurship Policy: Is Policy Formulation to Blame? Small Business Economics 43: 639–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arshed, Norin, Dominic Chalmers, and Russell Matthews. 2018. Institutionalizing Women’s Enterprise Policy: A Legitimacy-Based Perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43: 553–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bako, Mandy Jollie, and Jawad Syed. 2018. Women’s Marginalization in Nigeria and the Way Forward. Human Resource Development International 21: 425–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basant, Rakesh. 2018. Exploring Linkages between Industrial Innovation and Public Policy: Challenges and Opportunities. Vikalpa 43: 61–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaji, Stephen Dele. 2014. Intent to action: Overcoming the barriers to universal basic education policy implementation in Nigeria. Ph.D. thesis, The Graduate Research School of Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Bolaji, Stephen D., Jan R. Gray, and Glenda Campbell-Evans. 2015. Why Do Policies Fail in Africa Why Do Policies Fail in Nigeria? Journal of Education & Social Policy 2: 57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Boyi, Abubakar Aminu. 2019. Feminization of Poverty in Nigeria and Challenges of Sustainable Development and National Security. International Journal of Development Strategies in Humanities, Management and Social Sciences 9: 155–65. [Google Scholar]

- Canagarajan, Sudharshan, John Ngwafon, and Saji Thomas. 1997. The Evolution of Poverty and Welfare in Nigeria, 1985–1992. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper Series 1715; Washington, DC: The World Bank. [Google Scholar]

- Central Bank of Nigeria. 2005. Monetary Policy: The Conduct of Fiscal Policy 2005: Central Bank of Nigeria. Available online: cbn.gov.ng (accessed on 5 June 2020).

- Chegwe, Emeke. 2014. A Gender Critique of Liberal Feminism and Its Impact on Nigerian Law. International Journal of Discrimination and the Law 14: 66–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damon, Amy, Paul Glewwe, Suzanne Wisniewski, and Bixuan Sun. 2016. Education in Developing Countries—What Policies and Programmes Affect Learning and Time in School? Stockholm: Elanders Sverige AB. [Google Scholar]

- Dao, Minh Quang. 2017. The impact of public policies and institutions on economic growth in developing countries: New empirical evidence Bulletin of Applied Economics. Risk Market Journals 4: 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Drine, Imed, and Mouna Grach. 2012. Supporting Women Entrepreneurs in Tunisia. European Journal of Development Research 24: 450–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edoho, Felix Moses. 2015. Entrepreneurship and Socioeconomic Development Catalyzing African Transformation in the 21st Century. African Journal of Economic and Management Studies 6: 127–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efobi, Uchenna R., Ibukun Beecroft, and Scholastica N. Atata. 2019. Female Access and Rights to Land, and Rural Non-Farm Entrepreneurship in Four African Countries. African Development Review 31: 179–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhator, Eghosa. 2018. Protection and Promotion of Women’s Rights in Nigeria: Constraints and Prospects. Hague: Eleven International Publishing, pp. 1–29. [Google Scholar]

- Eniola, Bolanle Oluwakemi. 2018. Gender Parity in Parliament: A Panacea for the Promotion and Protection of Women’s Rights in Nigeria. Frontiers in Sociology 3: 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, Päivi, and Anne Kovalainen. 2016. Qualitative Methods in Business Research. London: SAGE Publications Ltd., pp. 1–355. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, Colette, Barbara Orser, Susan Coleman, and Lene Foss. 2017. Women’s Entrepreneurship Policy: A 13 Nation Cross-Country Comparison. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 9: 206–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudson, Bob, David Hunter, and Stephen Peckham. 2019. Policy Failure and the Policy-Implementation Gap: Can Policy Support Programs Help? Policy Design and Practice 2: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyytinen, Ari, and Otto Toivanen. 2005. Do Financial Constraints Hold Back Innovation and Growth? Evidence on the Role of Public Policy. Research Policy 34: 1385–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idike, Adeline Nnenna, Remi Chukwudi Okeke, Cornelius O. Okorie, Francisca N. Ogba, and Christiana A. Ugodulunwa. 2020. Gender, Democracy, and National Development in Nigeria. SAGE Open 10: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ileana, Anastase Badulescu, and Grigorut Cornel. 2017. Public Policies on Unemployment. Ovidius University Annals, Economic Sciences Series; Constanța: Ovidius University of Constantza, Faculty of Economic Sciences, pp. 124–26. [Google Scholar]

- ILO. 2012. Women’s Entrepreneurship Development and Gender Equality. Small 3: 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Link, Albert N., Derek R. Strong, and Boston Delft. 2016. Gender and Entrepreneurship: An Annotated Bibliography. Foundations and Trends R in Entrepreneurship 12: 287–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackay, Melissa, and Louise Shaxton. 2011. Understanding and Applying Basic Public Policy Concepts: A Report Published by University of Guelph, and Delta Partnership. Available online: https://atrium.lib.uoguelph.ca/xmlui/handle/10214/23740 (accessed on 28 November 2021).

- Makinde, Olusesan Ayodeji, Cheluchi Onyemelukwe, Abimbola Onigbanjo-Williams, Kolawole Azeez Oyediran, and Clifford Obby Odimegwu. 2017. Rejection of the Gender and Equal Opportunities Bill in Nigeria: A Setback for Sustainable Development Goal Five. Gender in Management 32: 234–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckeown, Anthony. 2016. Chapter 5—Investigating Information Poverty at the Macro Level: Part 1, Overcoming Information Poverty. Witney: Chandos Publishing, pp. 95–114. [Google Scholar]

- Medie, Peace A. 2013. Fighting Gender-Based Violence: The women’s movement and the Enforcement of Rape Law in Liberia. African Affairs 112: 377–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medie, Peace A. 2019. Introduction: Women, Gender, and Change in Africa. African Affairs, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minniti, Maria, and Wim Naudé. 2010. What Do We Know about the Patterns and Determinants of Female Entrepreneurship across Countries? European Journal of Development Research 22: 277–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mordi, Chima, Ruth Simpson, Satwinder Singh, and Chinonye Okafor. 2010. The Role of Cultural Values in Understanding the Challenges Faced by Female Entrepreneurs in Nigeria. Gender in Management: An International Journal 25: 5–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrisson, Christian, and Johannes P. Jütting. 2005. Women’s Discrimination in Developing Countries: A New Data Set for Better Policies. World Development 33: 1065–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muoghalu, Caroline Okumdi, and Friday Asiazobor Eboiyehi. 2018. Assessing Obafemi Awolowo University’s Gender Equity Policy: Nigeria’s under-Representation of Women Persists. Issues in Educational Research 28: 990–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Naude, Wim. 2010. Promoting Entrepreneurship in Developing Countries: Policy Challenges. Helsinki: United Nations University, World Institute for Development Economics Research UNU-WIDER, pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Naude, Wim. 2013. Entrepreneurship and Economic Development: Theory, Evidence and Policy. IZA Discussion Paper. Maastricht: UNU-MERIT University of Maastricht Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics (NBS). 2018. Statistical Report on Women and Men in Nigeria; Garki: National Bureau of Statistics, pp. 1–99.

- Nelson, Chijioke. 2020. Nigeria and poor gender-based budgeting records. The Guardian, January 27. [Google Scholar]

- Nour, Nawal M. 2015. Female Genital Cutting impact on women’s health. Seminar Reproductive Medicine 7–33: 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nwokocha, Ezebunwa E. 2007. Male-Child Syndrome and the Agony of Motherhood among the Igbo of Nigeria. International Journal of Sociology of the Family 33: 219–34. [Google Scholar]

- OECD/European Union. 2017. Policy Brief on Women’s Entrepreneurship. Luxembourg: OECD/European Union. Publications Office of the European Union. [Google Scholar]

- Ogunnaike, James. 2020. Obasanjo-laments-nigerias-14-million-out-of-schoolchildren. Vanguard, November 28. [Google Scholar]

- Okeke, Tochukwu Christopher, Ugochukwu Bond Anyaehie, and Chijioke Cyril Ezenyeaku. 2012. An Overview of Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research 2: 70–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okeke-Uzodike, Obianuju E., Okeke-Uzodike Ufo, and Catherine Ndinda. 2018. Women Entrepreneurship in Kwazulu-Natal: A Critical Review of Government Intervention Politics and Programs. Journal of International Women’s Studies 19: 147–64. [Google Scholar]

- Oloyede, Oluyemi. 2016. Monitoring Participation of Women in Politics in Nigeria; Garki: National Bureau of Statistics. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/gender/Finland_Oct2016/Documents/Nigeria_paper.pdf (accessed on 4 September 2020).

- Omoluabi, Elizabeth, Olabisi Idowu Aina, and Marie Odile Attanasso. 2014. Gender in Nigeria’s Development Discourse: Relevance of Gender Statistics. Etude de La Population Africaine 27: 372–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Onyeji, Ebuka. 2019. Female Politicians’ Fault Buhari’s Ministerial List of Seven Women 2019. Premium Times. July 24. Available online: https://www.premiumtimesng.com/news/top-news/342611-female-politicians-fault-buharis-ministerial-list-of-seven-women.html (accessed on 20 December 2020).

- Orloff, Ann Shola, and Bruno Palier. 2009. The Power of Gender Perspectives: Feminist Influence on Policy Paradigms, Social Science, and Social Politics. Social Politics 16: 405–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panda, Swati. 2018. Constraints Faced by Women Entrepreneurs in Developing Countries: Review and Ranking. Gender in Management 33: 315–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Para-Mallam, Oluwafunmilayo J. 2007. Nigerian Women Speak-A Gender Analysis of Government Policy on Women. Saabrucken: VDM Verlag Dr. Mueller e.K, pp. 1–400. [Google Scholar]

- Para-Mallam, Funmi J. 2010. Promoting Gender Equality in the Context of Nigerian Cultural and Religious Expression: Beyond Increasing Female Access to Education. Compare 40: 459–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, Katarina, Helene Ahl, Karin Berglund, and Malin Tillmar. 2017. In the Name of Women? Feminist Readings of Policies for Women’s Entrepreneurship in Scandinavia. Scandinavian Journal of Management 33: 50–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philips, S. U. 2001. Gender Ideology: Cross-Cultural Aspects. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences. Tucson: University of Arizona, pp. 6016–20. [Google Scholar]

- Profeta, Paola. 2020. Gender Equality and Public Policy. Munich: Ifo Institute—Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich, vol. 21, pp. 37–40. [Google Scholar]

- Rogo, Khama, Tshiya Subayi, and Nahid Toubia. 2007. Female Genital Cutting, Women’s Health and Development the Role of the World Bank. Washington, DC: The World Bank Washington. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE Publications Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Schofield, Toni, and Susan Goodwin. 2005. Gender Politics and Public Policy Making: Prospects for Advancing Gender Equality. Policy and Society 24: 25–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soetan, Funmi, and Bola Akanji. 2019. Chapter 1 Gender inequality in Socioeconomic Development of the Nigerian Nation State: An empirical glimpse. In Through the Gender Lens: A Century of Social and Political Development in Nigeria. Edited by Funmi Soetan and Bola Akanji. A Book Review. Lanham: Lexington Books, vol. 34, pp. 536–38. [Google Scholar]

- Techane, Meskerem Geset. 2017. Economic Equality and Female Marginalisation in the SDGs Era: Reflections on Economic Rights of Women in Africa. Peace Human Rights Governance 1: 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- Tende, Sam B. 2014. Government Initiatives toward Entrepreneurship Development in Nigeria. Global Journal of Business Research 8: 109–20. [Google Scholar]

- The World Bank. 1996. Nigeria-Poverty in the Midst of Plenty: The Challenge of Growth with Inclusion: A World Bank Poverty Assessment. Washington, DC: The World Bank, p. 14733. [Google Scholar]

- UNDP. 2013. Poverty Reduction, Humanity Divided: Confronting Inequality in Developing Countries. New York: United Nations Development Programme Bureau for Development Policy, United Nations Plaza, pp. 162–93. [Google Scholar]

- UNICEF. 2017. State of the World’s Children: The Challenge: One in Every Five of the World’s Out-of-School Children Is in Nigeria. Education UNICEF Nigeria. UNICEF for Every-Child-75-Nigeria. Available online: https://www.unicef.org/nigeria/education (accessed on 5 December 2020).

- Nations United (OHCHR). 2018. Integrating a Gender Perspective into Human Rights Investigations Guidance and Practice. New York and Geneva: Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 1995. Paper presented at Fourth World Conference on Women, Beijing, China, September 4–15. United Nations Report. New York: United Nation Women Watch. Available online: https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/pdf/Beijing%20full%20report%20E.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2020).

- Vossenberg, Saskia. 2013. Working Paper No. 2013/08 Women Entrepreneurship Promotion in Developing Countries: What Explains the Gender Gap in Entrepreneurship and How to Close It? Maastricht: Maastricht School of Management, pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Vossenberg, Saskia. 2014. Beyond the Critique: How Feminist Perspectives Can Feed Entrepreneurship Promotion in Developing Countries. Maastricht School of Management Working Paper Series; Maastricht: Maastricht School of Management, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Welter, Friederike. 2004. The Environment for Female Entrepreneurship in Germany. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 11: 212–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaya, Sanni, and Bishwajit Ghose. 2018. Female Genital Mutilation in Nigeria: A Persisting Challenge for Women’s Rights. Social Sciences 7: 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ewoh-Odoyi, E. How Gender Is Recognised in Economic and Education Policy Programmes and Initiatives: An Analysis of Nigerian State Policy Discourse. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120465

Ewoh-Odoyi E. How Gender Is Recognised in Economic and Education Policy Programmes and Initiatives: An Analysis of Nigerian State Policy Discourse. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(12):465. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120465

Chicago/Turabian StyleEwoh-Odoyi, Ethel. 2021. "How Gender Is Recognised in Economic and Education Policy Programmes and Initiatives: An Analysis of Nigerian State Policy Discourse" Social Sciences 10, no. 12: 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120465

APA StyleEwoh-Odoyi, E. (2021). How Gender Is Recognised in Economic and Education Policy Programmes and Initiatives: An Analysis of Nigerian State Policy Discourse. Social Sciences, 10(12), 465. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120465