Abstract

Aging audiences and the shift of news consumption to an online paradigm have led to the need of finding strategies to engage aging readers with online news by assessing their news consumption habits and identifying the potential for digital platforms to assist the reader’s journey, i.e., the activities performed from access to the information to the relatedness and shareability of the news content. It is well established that the use of game elements and game thinking within the context of a community can capture the user’s attention and lead to behavioral engagement toward repetitive tasks. However, information about the design implications of socially gamified news to the aging reader’s experience is still lacking. Using a development research approach, we implemented a prototype that socially gamifies news to support the aging reader experience based on a pre-assessment survey with 248 participants about their news consumption habits and motivations. We then validated the prototype with six market-oriented representatives of Portuguese newspapers and eleven adults aged 50 and over. A model for onboarding a reader’s 6-step journey (read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience) within the context of a Senior Online Community using gamification is proposed. The game elements used can inform the design of a much more personalized experience of consuming news and news behavioral engagement.

1. Introduction

In light of social distancing measures during COVID-19 and the prevalence of digital platforms to access daily basis services (e.g., access to online social support, access to health information) (Seifert 2020), new challenges are posed to the Human–Computer Interaction field to meet users’ context and daily-living activities, of which online news is no exception. Moreover, the increasing aging population and the importance of reading news in the daily life of older adults to keep them informed and relate with society (Lin et al. 2014) amplify the need to find digitally-mediated strategies to enhance the reader’s experience. While the reading activity has been the focus when assessing news consumption (Bergström 2020), other equally important social dimensions inherent to news consumption (i.e., reacting, discussing and relating) have been quite neglected, which are likely to affect the news reading experience.

Within this context, gamification, i.e., the use of game elements in contexts that go beyond the entertainment purpose (Deterding et al. 2011), can be a digitally-mediated solution to assist the reader’s experience in a social context. Indeed, social relatedness and discussion with the news content brought with gamification are of particular importance given that there seems to be a general difficulty in detecting lies and screening misinformation or manipulated images in later adulthood (Brashier and Schacter 2020).

Moreover, the growing paradigm change of news to online has also led to the need to reinvent the newsrooms and transform journalism practices, e.g., immediacy in news divulgation (Siapera and Veglis 2012), visual journalism and news storytelling (Caldwell and Zappaterra 2014). If, on the one hand, online journalism can reach a larger audience, on the other hand, a much more personalized experience that considers readers’ context and their engagement within the context of a community is also necessary.

There are a number of publications (Barnes 2015; Bergström 2020; Conill and Karlsson 2015) that highlight that an aging audience of online news is growing, especially in terms of the consumption of digital morning and local news, but social anchoring and relatedness to news content is still challenging. Thus, gamification is presented as a way to regularly engage audiences with news content (Conill 2016). It is worth noting, however, that caution must be applied when gamifying news given the possibility of spreading fake news and politicizing particular news sources and, as such, a value-sensitive design (Manders-Huits 2011) should not be overlooked. In fact, the growing use of personalized algorithms can promote echo chambers of thoughts, while limiting and reinforcing a shared narrative among users (Cinelli et al. 2021). Nonetheless, Zichermann (2019) proposes a gamification system to mitigate the spread of fake news based on a trust score and an up- and down-vote system—as in the case of Reddit (Cinelli et al. 2021). Consequently, it is suggested that, as long as the news feeds do not undergo a personalization of interest-based content but rather user and reader-oriented ratings, there is a possibility of slowing the spread of misinformation.

In terms of the target group, most of the gamification studies tend to focus on a young audience (e.g., Toscani et al. 2018; Cesário et al. 2017; Duarte-Hueros et al. 2020; Guardia et al. 2019), while only little published data has been available on how older populations tend to access news (e.g., Bergström 2020; Fisher et al. 2021) and gamified systems (e.g., Altmeyer et al. 2018; De Vette et al. 2018; Moser et al. 2015; Kappen 2015). To address this research gap, the authors designed, developed and deployed a socially gamified news system to support the aging reader experience within the context of a Senior Online Community.

Regarding the concept of Senior Online Communities, these can be defined as the usage of online spaces in which social interactions between members rely on the shared purpose of aging actively and ensure social support in daily living (Nimrod 2010), taking into account age-related changes in platform design (Fisk et al. 2009). Examples include Stitch1, Older is wiser2, Buzz 503 and miOne4. The latter has the particularity of addressing the different domains of active aging—i.e., health, sense of security and participation in society (WHO 2002)—and incorporating the gamified strategy proposed in this paper to engage its members with online news.

Specifically, this paper gives insights into how gamification can be used to foster interaction and engage older adults with online news, while aiming to answer the following research question, How can gamification engage adult learners at the Universities of the Third Age with online news?, and achieving its corresponding goals: [i] characterize the older adults’ contexts of gamification, Internet, social media and online news consumption; and [ii] design, develop and assess a gamification strategy to the news for an online community addressed to older adults. To achieve this purpose, a development research framework (Van der Maren 2004) was used and the results of the gamification deployment led to some indicators as to what the older adults tend to value in a personalized experience of consuming news and news behavioral engagement. A 3-step was considered in this research: Step 1 began with the analysis and evaluation of the situation, in which there was a pre-assessment with 248 participants about their news consumption habits and motivations. Step 2 was relative to the conception and design of the prototype to assist the aging reader’s experience, whereas Step 3 referred to its implementation and validation with Portuguese representatives of the newspaper’s industry and eleven adults aged 50 and over within the context of the Senior Online Community miOne, leading to a model for onboarding a reader’s 6-step journey.

Specifically, we make the following contributions:

- A prototype that socially gamifies news to support the aging reader’s experience;

- A model for onboarding a reader’s 6-step journey (read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience) within the context of a Senior Online Community using gamification.

This paper is structured in six sections, including the Introduction and Conclusion. Section 2, Related Work, situates the research into the literature regarding the use of gamification in online communities and journalism. Section 3, Method, describes the procedures undertaken in the development research method used, including the analysis and evaluation of the situation, conception and design of the prototype, and implementation and evaluation. The evaluation procedures and data collection are also presented. Then, findings are reported, followed by a discussion, limitations, and future directions.

2. Related Work

In the context of this research, a gamification system will be applied within the context of an online community to foster interaction and engage older adults with online news. Given this purpose, both social aspects of gamification and its application in online news platforms are covered. In this section, we provide a brief overview of the literature about gamification in online communities, its application in online news and usage by older adults.

2.1. Gamification in Online Communities

Game elements and game thinking have been applied to the context of online communities to encourage members’ participation and reward community activities (Cavusoglu et al. 2015), while helping to improve engagement by (a) facilitating and accelerating feedback; (b) providing well-defined and simple goals and rules to play; (c) creating a narrative that guides the users, while captivating and engaging them; and (d) challenging while inducing a feeling of enjoyment (Deterding et al. 2011 as cited in Barnes 2015).

Gamification may also constitute a way to give visibility to the members’ activities within online communities and encourage social modeling through the use of badges, leaderboards, among other elements (Bista et al. 2014). For example, the use of badges in online communities is commonly widespread, as it is in the case of Reddit5—which gives honorary awards for worthy contributions; Campus by Fundação Altice6 (previously entitled SAPO Campus)—which adopted a badge-based strategy, allowing to highlight the learning path held by each student (Araújo et al. 2017); Khan Academy7, that rewards user’s behaviors through badges, assigned for certain actions such as earning points, achieving mastery in exercises or even building a community; and a Government Online Community (Bista et al. 2012), in which Bista and their colleagues applied temporary and permanent badges, concluding that these incite participation and return to the platform.

Moreover, other examples should be considered regarding the promotion of engagement in online communities, as it is in the case of Peoople8, which implements two simple mechanisms that can be used not only to motivate and engage users to use the app but also to promote responsible behaviors: (i) four different levels (i.e., Rookie, Influencer, Unicorn and Star) that can be completed when challenges are fulfilled and (ii) a wallet that is filled with money as people interact with the app. Additionally, Reddit has a wide range of gamified elements, such as Awards9—being a way for redditors, i.e., Reddit’s users, to recognize other redditors’ content, ‘Karma’ points—earned for each posts’ upvote, promoting community participation (Morrison and Hayes 2013) and ‘Reddit coins’10—a virtual good that can be bought with physical money and exchanged for various types of Awards. The application of gamification in the StackOverflow Q&A Community has also shown to be effective to stimulate voluntary participation (Cavusoglu et al. 2015). Nevertheless, social recognition beyond these aforementioned rewarding systems seems to be key to advance from extrinsic to intrinsic motivations (Cordero-Brito and Mena 2018).

In brief, a level designed system associated to missions and awarded actions have been suggested in literature to encourage members’ participation in the context of online community and enable social modeling. Beyond activity metrics, community-endorsed rewards seem to enhance the members’ relatedness to the transmitted content.

2.2. Gamification in News

Similar to online communities, news platforms have also been using game elements as a way to engage their readers. Progression levels, progression bars, points, levels, badges, leaderboards and community-shared goals—that have been used to reward readers (Sotirakou and Mourlas 2015), give feedback on their current state and translate it into the readers’ reputation (Conill 2016)—are part of the vast portfolio studied not only by the industry but also by the academic community.

The use of game elements in the journalism context takes a variety of forms. Newsgames, i.e., games which illustrate current news events (Treanor and Mateas 2009), are an important example of how to generate empathy, connection and awareness for issues that would otherwise not be possible. The example of the game developed by Al Jazeera in 2014 can be a great contribution to the ongoing research. It consisted of an interactive investigation and, as users progress in the game, the story is deciphered and cumulative points are earned—‘Investigation Points’ (Conill and Karlsson 2015), levels are progressed (Conill 2016) and content is unlocked (Conill 2016; Conill and Karlsson 2015). Therefore, it becomes a storytelling technique that immerses and engages its readers (Conill 2016). This example, despite being a game, presents engagement-promoting elements that can easily fit into other contexts—such as a gamification system.

Additionally, gamification can also be one form of the usage of game elements in the journalism environment. Conill and Karlsson (2015) emphasize the following benefits of gamifying news: (i) benefiting business logics and (ii) boosting users’ engagement. Badges are, undoubtedly, the most commonly used mechanic—e.g., The Times of India used it to maintain their readers’ loyalty (Conill 2016); The Huffington Post used them as a “a fun new way of recognizing and empowering the community” (Huffington 2010, para. 3), while triggering political discussion on the United Kingdom’s issues (Jones and Altadonna 2012); and BuzzFeed uses content-categorization badges as a way to translate the interaction a certain post had—something that Foxman (2015) studied as a good example of game technics used to engage, inform and educate its readers. Moreover, leaderboards also play a significant role in the gamified news world, as it is in the case of a Gamified News Read for Mobile Devices developed by Sotirakou and Mourlas (2015), in which readers with the best performance had the possibility to join a leaderboard, highlighting the utmost importance given to social recognition in order to lead to self-motivation (Sotirakou and Mourlas 2015). Meanwhile, The Guardian used a leaderboard with the top readers that performed a community-shared goal to classify political documents that were leaked in 2009 (Conill 2016).

Game elements can be also used to help in community fact checking and improve news literacy, and hence assist the end users of a community to distinguish credible content from misleading information (Micallef et al. 2021; Zichermann 2019).

In all the studies reviewed, gamification can enable scaffolding in the readers’ activity—e.g., use of progression levels, content categorization as occurred in BuzzFeed, content-categorization badges and ranking readers’ activities (leaderboard). However, an integration of gamification as a whole system and its interconnection with different activities that define the readers’ experience is still lacking.

2.3. Gamification and Older Adults

Gamification has been pinpointed to be an effective strategy to foster older adults’ cognitive training and health self-management (Koivisto and Malik 2020). Much of the research up to now has been focused on the use of gamification-driven strategies in health and potential benefits for physical, cognitive and social wellbeing (Boot et al. 2016; Gerling and Masuch 2011; Kappen et al. 2018; Pannese et al. 2016). However, its usage to foster older adults’ participation in online communities or engaging with reading activities is still lacking.

Previous research on the use of gamification in later adulthood has highlighted the potential benefits: improve the cognitive and socio-emotional state (Altmeyer et al. 2018; Koivisto and Malik 2020; Martinho et al. 2020), improve personalized healthcare (Martinho et al. 2020), enable skills scaffolding (Kostopoulos et al. 2018), capture interest in activities and facilitate social interactions (Altmeyer et al. 2018; Martinho et al. 2020; Méndez et al. 2020). By contrast, challenges associated to such usage include digital inclusion and unfamiliarity with game conventions (Barambones et al. 2020; Martinho et al. 2020).

When designing a gamified system for this target group, one should take into account the following considerations: prioritize social interactions, immediate feedback, progression and rewards (Martinho et al. 2020), enable personal mastery and opt for failure avoidance (Barambones et al. 2020).

According to Minge and Cymek (2020), the following gamification elements had high acceptance in older adults: progress visualization and having different levels of difficulty for activities. Age-related impairments should also be considered (Fisk et al. 2009; Pak and McLaughlin 2011) when designing these gamified systems, such as cognitive deterioration (e.g., deterioration of working memory), visual difficulties (e.g., increased difficulty in distinguishing color contrasts) and movement impairments (on average, older adults take 1.5 to 2 times longer than youngsters to perform the same task and movement control is less precise).

In a broad sense, the literature revealed few studies which consider older adults’ community context (Koivisto and Hamari 2014) and a digitally-mediated solution that meets their interests was proposed (Nimrod 2014). In this sense, courses of action are needed to familiarize this target group to gamification elements and promote a motivational environment and behavioral changes (Kazhamiakin et al. 2016), with impact on physical, psychological and social activities.

Building on top of this previous work on gamification and online communities, news and older adults, this research provides further insights on the way a gamified strategy can affect the reader’s 6-step journey (read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience) within the context of a Senior Online Community. Hence, the following sections report on the development of a gamification system applied to online news platforms based on the older adults’ motivations and context. This is particularly important to enable aging audiences’ social relatedness and discussion with the news content provided within the context of a community.

3. Method

The current study is part of the SEDUCE 2.0 research project that aims (a) to assess the impact of psychosocial variables and online sociability of senior citizens through the use of Information and Communication Technologies and (b) contribute to the growing development of the miOne online community with the participation of senior citizens from Universities of the Third Age11.

Given the research question, How can gamification engage adult learners at the Universities of the Third Age with online news?, and the identified goals for this research (i.e., [i] characterize the older adults’ contexts of gamification, Internet, social media and online news’ consumption and [ii] design, develop and assess a gamification strategy to the news for an online community addressed to older adults), a development research framework (Van der Maren 2004), alongside evaluative and intervention research, was required to answer the study’s main goals, combining both quantitative (i.e., pre-assessment survey) and qualitative (i.e., interviews, field notes and participant observation) data collection tools. According to Oliveira (2006), one of the advantages and distinguished points of development research is its ability to combine other methodologies that may be useful for the research process.

The research approach adopted was the development of a product to be integrated in the miOne’s news platform, composed of three main steps: (i) analysis and evaluation of the situation—grounded in the literature review, related work and previous research in the area; (ii) conception and design of the prototype—in which the researchers designed a solution that met users’ needs while attempting to solve the research problem; and (iii) implementation and evaluation—a functional prototype was developed and tested by the end users.

In the following sections, each of the three steps previously mentioned will be described.

3.1. Step 1—Analysis and Evaluation of the Situation

After the literature review and analysis of related work, a group of 248 older adults were surveyed from 1 June of 2020 to 9 July of the same year to assess their familiarity with online news, gamification strategies, social media and games. It is relevant to note that this questionnaire was intended to be cross-sectional and to nourish the development of the prototype, since a general lack of information was found during the literature review. Therefore, a convenience sample was selected from 16 different countries (Australia, Austria, Brazil, Canada, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and the United States of America). The selection criteria was to fit within the age cohorts previously identified—pre-seniors (50–64 years old) (Lee et al. 2011), youngest-old (60–74 years old), middle-old adults (75–84 years old) and oldest-old (85+ years old) (Lee et al. 2018).

After questioning the demographic information (age, country of residence and gender), the following questions were posed: (1) Please indicate the frequency in which you perform the following activities (Access to the Internet/Social media/Online banking or other financial products, Read/Share/Discuss online news, Try to avoid news, Online search/shopping, Send and read emails, Use entertainment media)—5-item scale, ranging from 1-never to 5-always; (2) Which activities do you usually undertake when you access the news? (3) Do you use any points/card/coupon or discount mechanisms in your daily life?; (4) Do you use any mobile application in your everyday life that rewards you with challenges, badges, levels, points or leaderboards?—dichotomous question; (5) Do you usually play games?—dichotomous question; and (6) In an online social network/community, please indicate the importance of the following activities you would like to be valued for (activity in groups, frequency with which you talk to other people in the community, debate news, share news, react to news)—5-item scale of importance, ranging from 1—not at all important to 5—extremely important.

The average age of the sample is, approximately, 67 years old (minimum = 50; maximum = 91; SD = 8369), distributed over three continents—America, Europe and Oceania, with Portugal (60%; n = 146) and the United Kingdom (29%; n = 72) being the most predominant countries among all. A total of 57% (n = 140) of respondents identified as being female, 43% (n = 107) identified as being male, and 1 respondent identified with another gender (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic characterization of the sample.

Results suggest that the most perceived performed online activities by participants are, firstly, send and read emails (118 always and 93 often), followed by access the Internet (111 always and 120 often) and read online news (60 always and 106 often). Regarding the second question posed, i.e., Which activities do you usually do when you access the news?, the majority of participants revealed to read the news (89.11%; n = 211), followed by sharing news (34.68%; n = 86) and reacting to news (32.66%; n = 81).

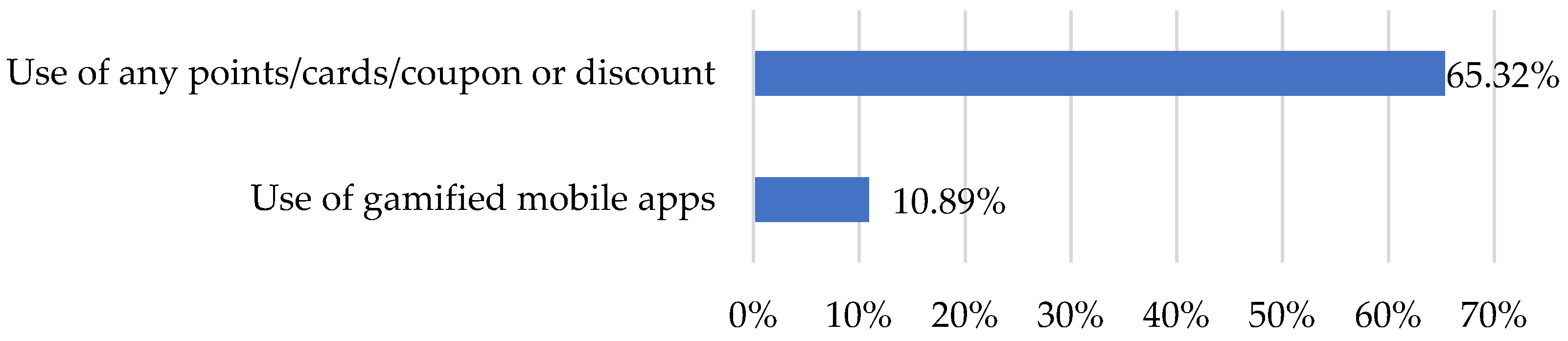

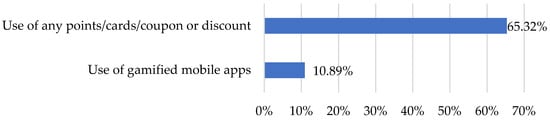

After assessing participants’ most performed activities, the next questions aimed to understand their relationship with game elements and gather foundations to design the gamification system. Regarding the third and fourth questions (i.e., Do you use any points/card/coupon or discount mechanisms in your daily life? and Do you use any mobile application in your everyday life that rewards you with challenges, badges, levels, points or leaderboards?), the results suggest that approximately 65% (n = 162) of participants use and recognize the use of gamified systems in daily life, whilst only approximately 11% (n = 27) recognize using gamified mobile apps (see Figure 1). Aiming to understand the familiarity with game elements through games themselves, the fifth question—Do you usually play games?—was posed, and 42.7% (n = 106) of the respondents stated playing games on a usual basis.

Figure 1.

Respondents’ contact with gamification systems (n = 248).

Lastly, when analyzing the results of the sixth and last question (see Table 2), it was found that group activity (7 extremely important and 40 very important) is the main activity respondents like to be valued for, followed by the frequency with which they talk to other people in the community (6 extremely important and 33 very important). Lastly, three other activities related to news emerged: debate news (3 extremely important and 32 very important), share news (5 extremely important and 31 very important) and react to news (6 extremely important and 26 very important). Therefore, it is verified that a great importance is given to discussion, expression of thoughts and sharing of opinions, which are important topics to consider when building a gamification system.

Table 2.

Main activities respondents like to be valued for (n = 248).

Overall, this data collection instrument allowed to understand the motivations of older adults regarding news consumption habits in online communities—i.e., contact with each other and sharing of information and opinions—and what activities should be targeted when developing a gamification system for online news—i.e., read, share and react. Furthermore, it allowed the conception of the reader’s journey, which will be explored in the next section. If the reader wants to deepen their knowledge on this subject, the detailed results have been published in (Regalado et al. 2021).

3.2. Step 2—Conception and Design of the Prototype

3.2.1. Gamification Prototype

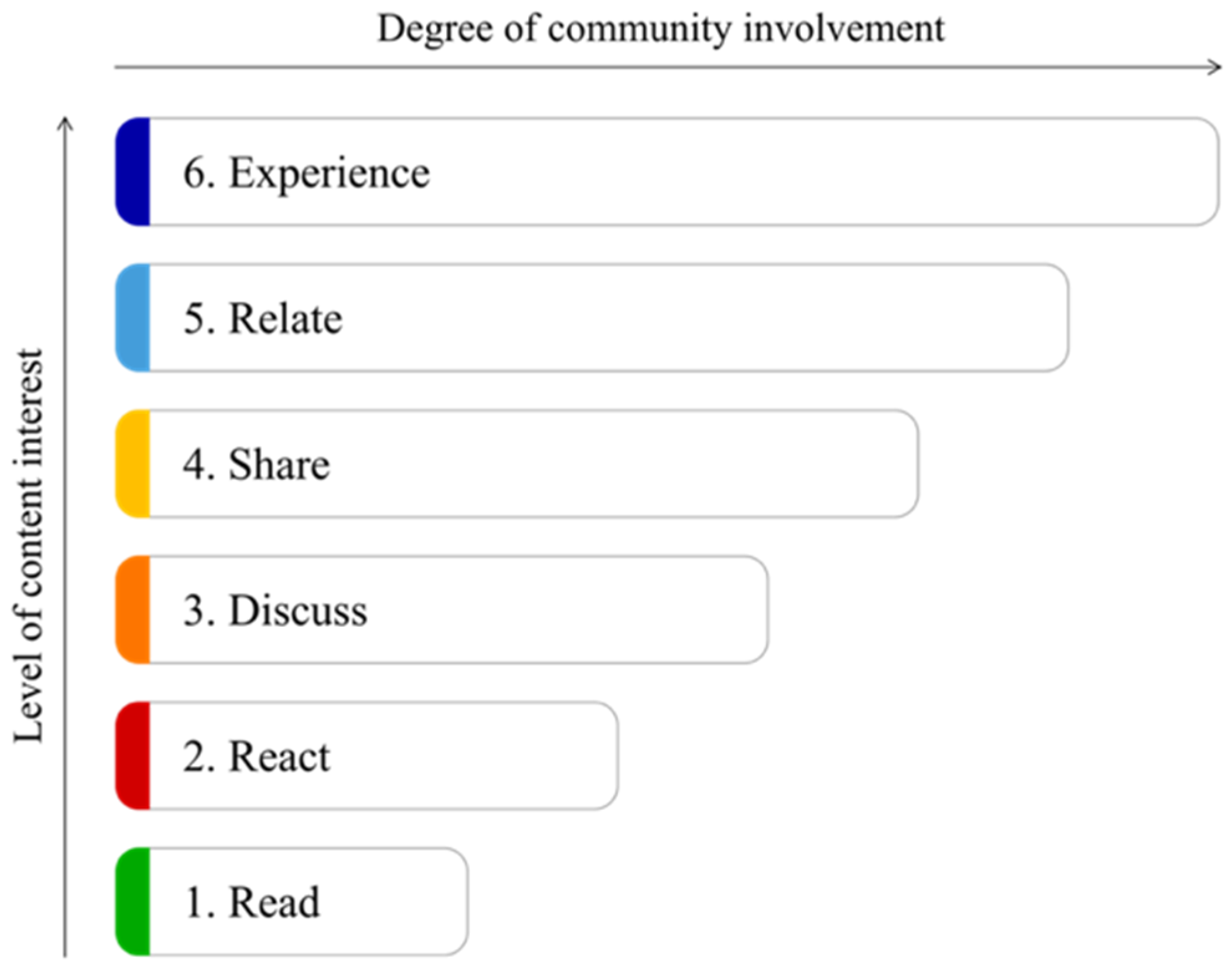

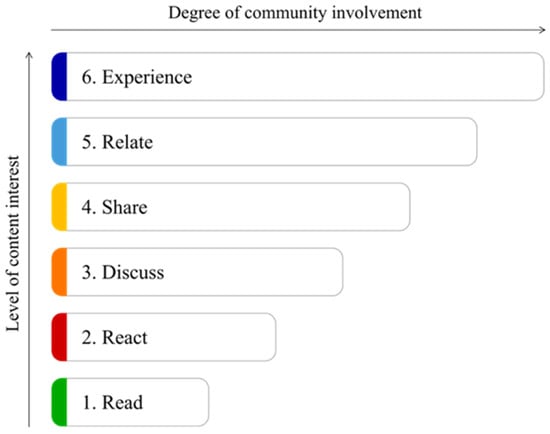

When analyzing the examples presented in the related work section (cf. Section 2), it is possible to identify some key elements that have been used and proved to be able to engage users: levels, points, leaderboards, badges, a status/level that recognizes the users’ achievements when completing different challenges, rewards assigned to other users’ content and rewards that have an impact outside the platform. Moreover, taking into account the previously described contributions in Step 1—the pre-assessment phase, where it was possible to identify the older adults’ motivations regarding online news consumption and the reader’s journey defined by the researchers as a result of the survey’s responses (see Figure 2)—a three-element gamification system was designed. The latter addresses the awards mechanism, which allows one to recognize user-produced content, while prioritizing social interactions, immediate feedback, progression and rewards (Martinho et al. 2020); levels with different degrees of difficulty, as suggested by Minge and Cymek (2020); and a leaderboard, promoting self-motivation and participation by highlighting users’ best performances (Conill 2016; Sotirakou and Mourlas 2015).

Figure 2.

Reader’s journey relating the level of content interest and the degree of community involvement. Retrieved from Gamifying News for the miOne Online Community (Regalado 2021).

Its main goals are to be a common reward engine, where all the elements are interconnected, and take into consideration the older adults’ age-related impairments, while motivating and engaging miOne’s news platform users in order to deepen their experience.

Therefore, three elements constitute the mentioned designed system: (i) awards, (ii) levels and (iii) a leaderboard.

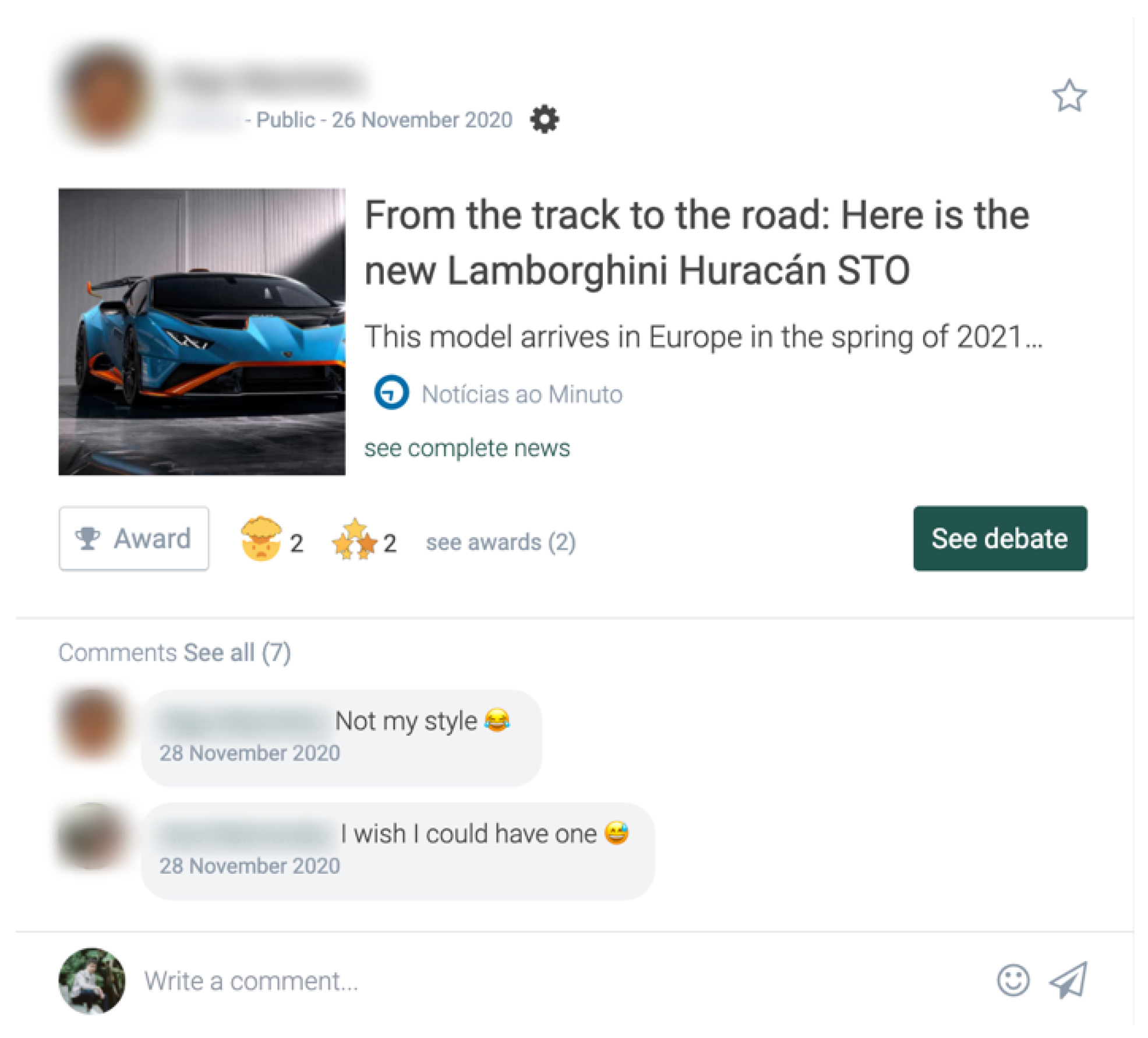

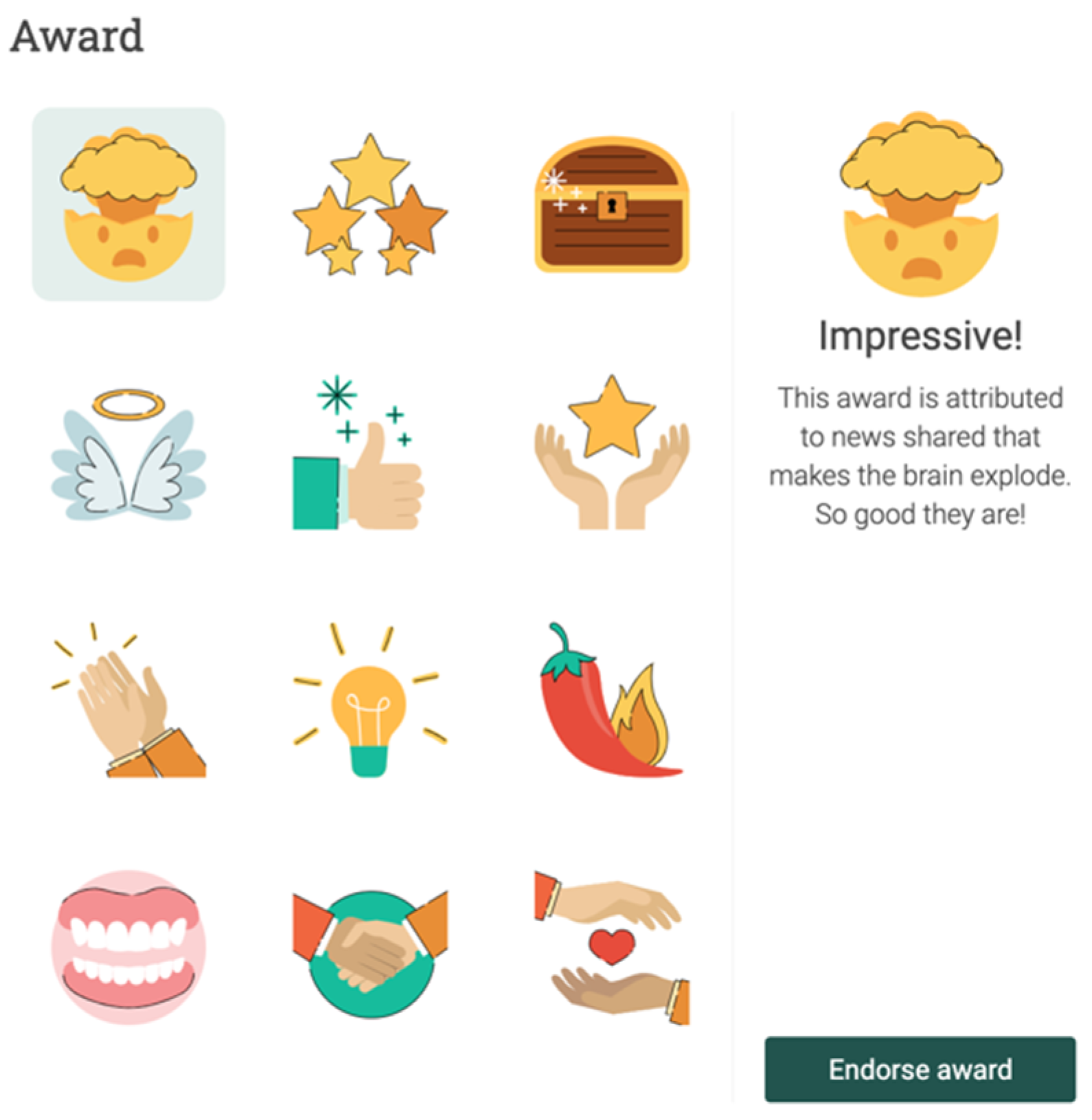

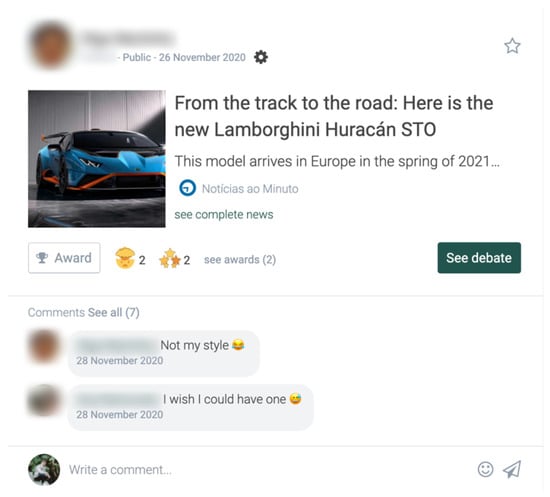

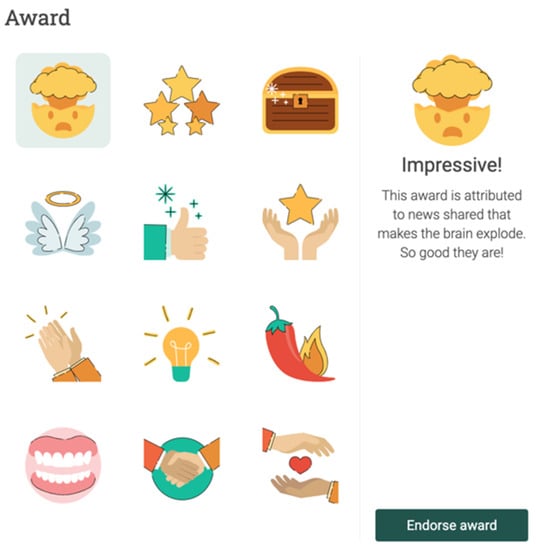

Awards

A set of twelve awards was designed and its main purpose is to allow users to reward each other for their news sharing, see Table 3. The awards have news-related themes, but, in general, can be applied to broader contexts. The design and contents were inspired by Reddit’s awards, while adapting and creating the content based on the aging readers’ context. Using the ‘Award’ button, which was added to every news activity, users can only attribute each award once per activity, see Figure 3. When the award button is clicked, a modal view is launched, and all the awards and their descriptions are listed, from where users can select one and assign it to the news activity, see Figure 4.

Table 3.

Description of the awards. Retrieved from Gamifying News for the miOne Online Community (Regalado 2021).

Figure 3.

Award scheme on news activities (Authors’ copyright).

Figure 4.

Endorsing awards modal (Authors’ copyright).

At the same time, social connection and recognition are important when building a gamification system, and thus users can view who assigned each award at the different news activities.

This gamification element is symbiotically interconnected with the two elements that will be further explored.

Levels

Another gamification mechanism was designed for this proposal, aiming to guide users through the platform and incite their engagement. This multi-level mechanism is composed of four different components:

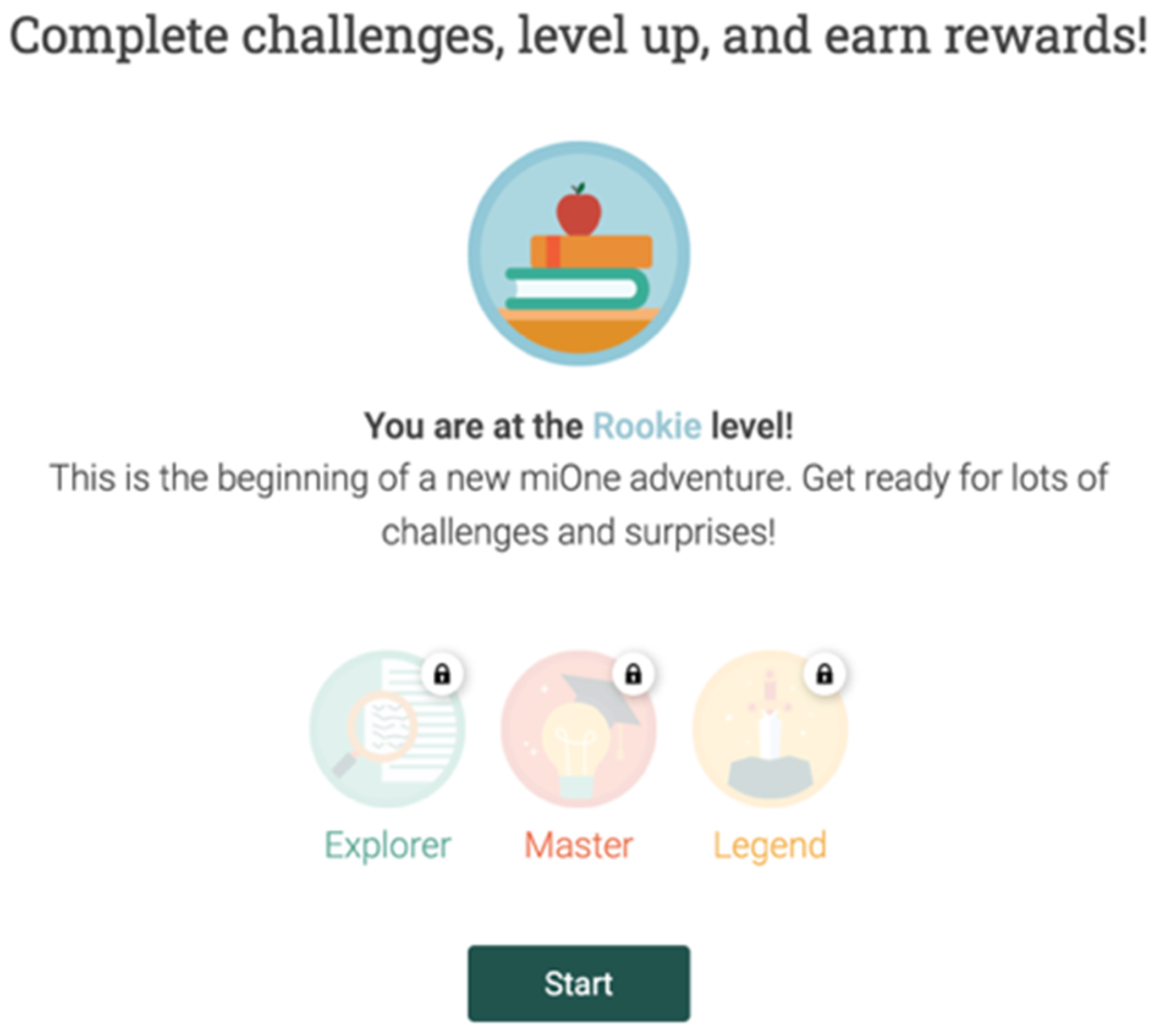

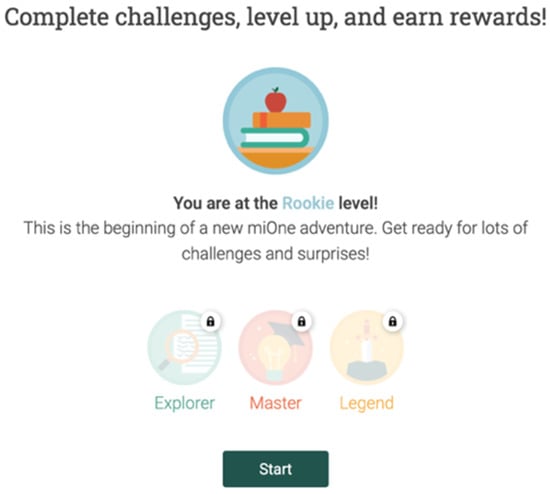

- Levels: Each level is defined by a variable set of missions. As the user advances, the difficulty progressively increases. A total of four levels was defined specifically for the miOne community (‘Beginner’, ‘Explorer’, ‘Master’ and ‘Legend’) (see Figure 5), while including news-related missions.

Figure 5. Initial modal with information about the various levels (Authors’ copyright).

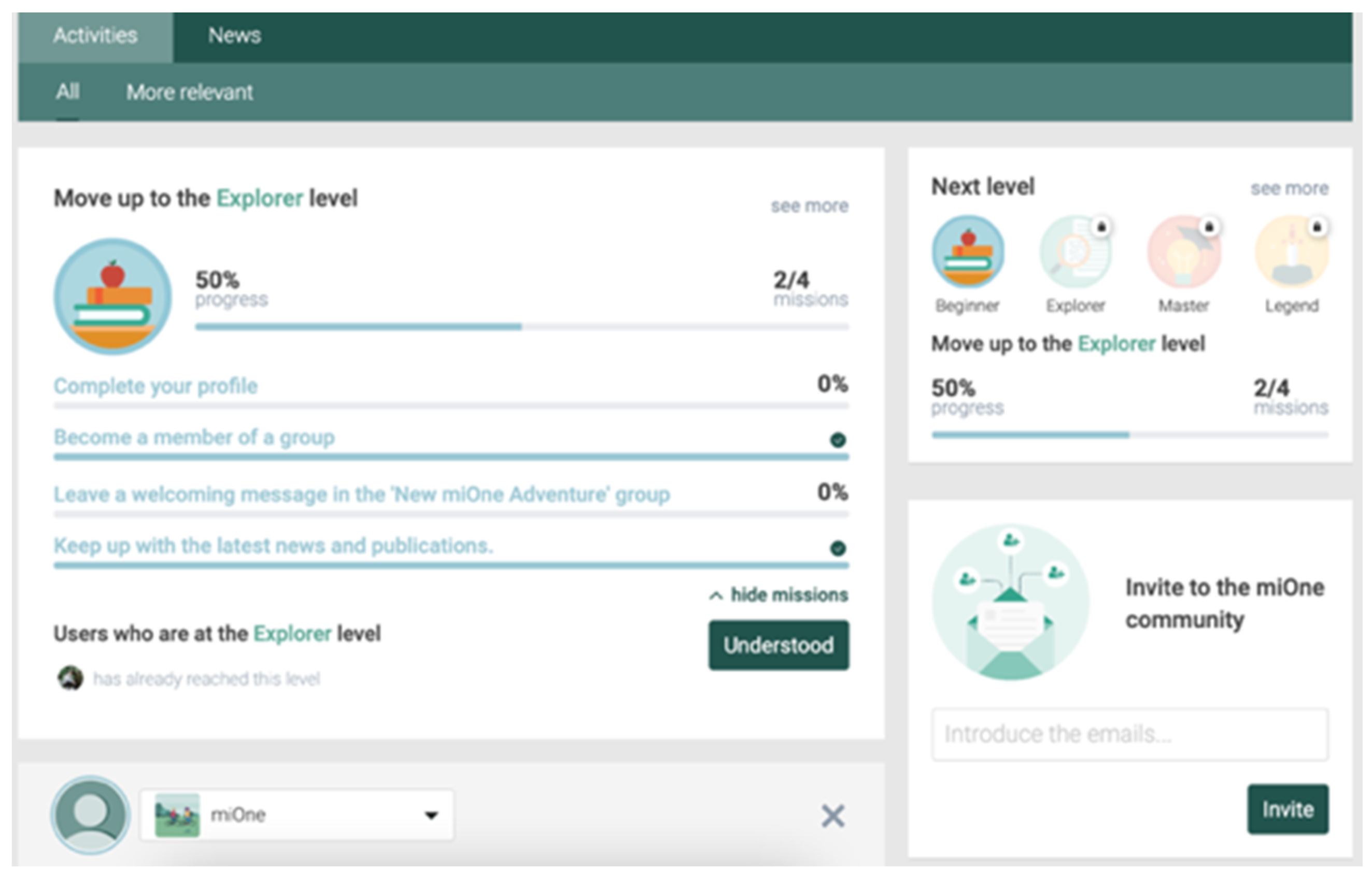

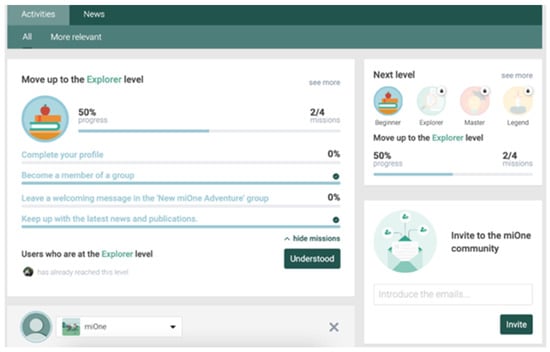

Figure 5. Initial modal with information about the various levels (Authors’ copyright). - Missions: These are the core and prime element of the system’s levels. To complete each level, users must perform a set of predefined missions. Similar to levels, these missions are progressively more difficult and more time demanding. To make users aware of what they need to achieve to advance through the missions and levels, while giving them constant feedback, aggregated information concerning users’ progress was added to the platform’s interface (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. miOne’s homepage with the mission progress summary (Authors’ copyright).

Figure 6. miOne’s homepage with the mission progress summary (Authors’ copyright). - Social recognition: A circle was added to the avatar with the color of the users’ levels, in order to allow the social recognition.

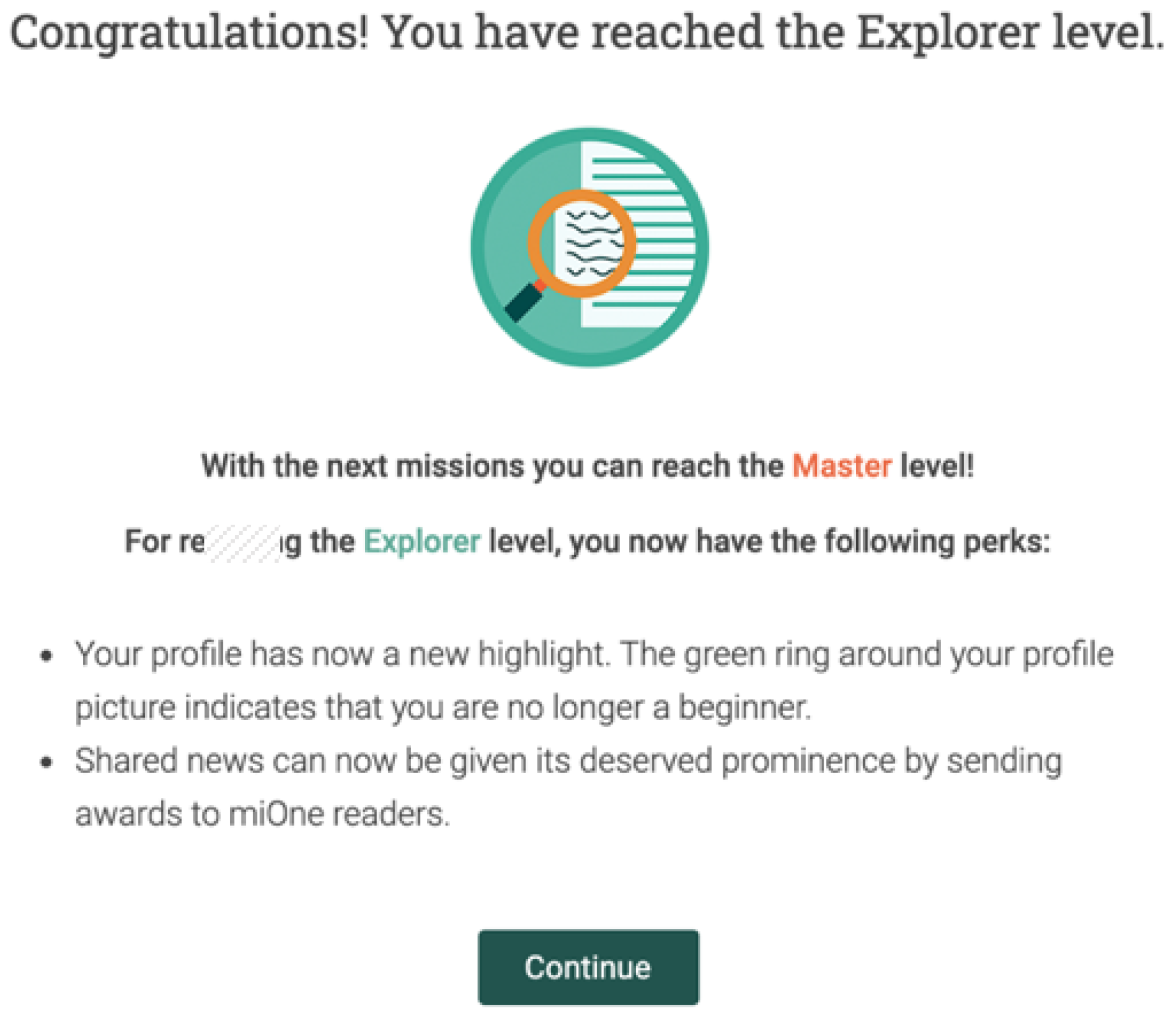

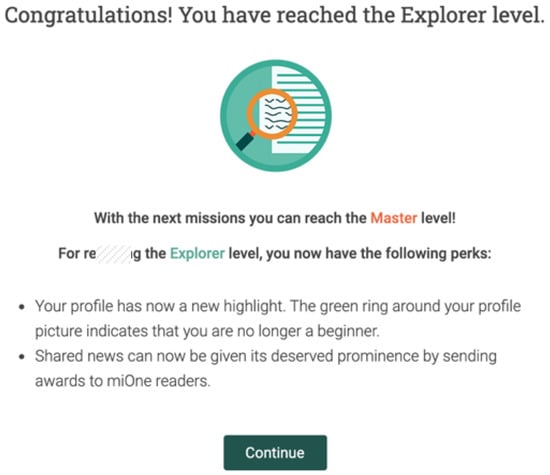

- Feedback: Feedback is one of the key elements in gamification systems, perpetuating a user’s participation. Whenever a user reaches a new level, a modal window is pushed and a notification is sent, encouraging further progress (see Figure 7).

Figure 7. Modal of leveling up to the Explorer level (Authors’ copyright).

Figure 7. Modal of leveling up to the Explorer level (Authors’ copyright).

Leaderboard

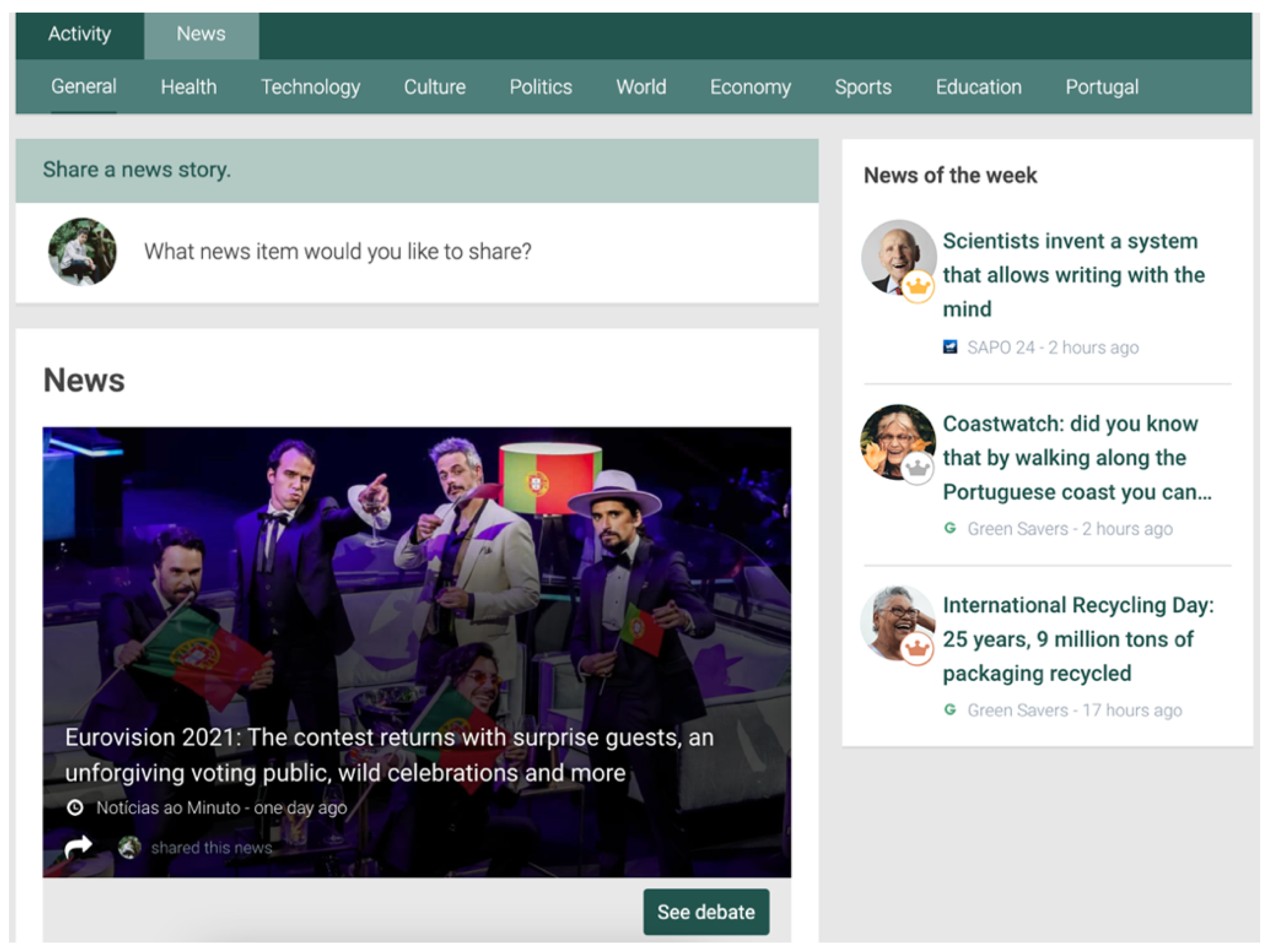

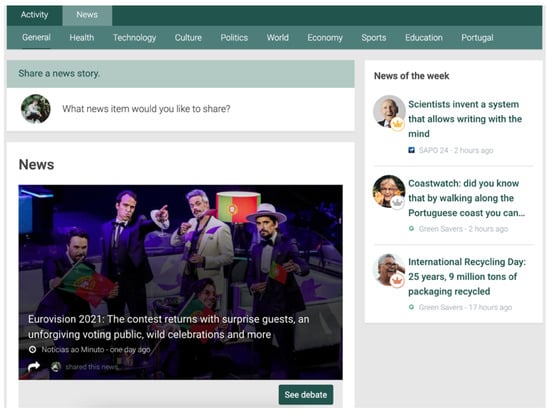

Considering a set of variables for each news activity—such as the number of unique comments, total comments, total awards, shares and how long ago it was published—a leaderboard was built and added to the sidebar of the news platform (see Figure 8). It features the most engaged news activities of the past seven days and provides a social highlight and recognition by associating the activities’ authors to each leaderboard entry.

Figure 8.

Leaderboard scheme (Authors’ copyright).

Returning to the reader’s journey, cf. Figure 2, it is important to understand how each of the presented gamification elements will foster its steps. The leaderboard allows readers to get in touch with the most community-relevant news—fulfilling the reading step—and relate with the shared content by allowing a clear identification of who produced each content—fulfilling the relating step. Moreover, the levels mechanism plays an important role in guiding users through the platform, inciting them to share new content and start new debates—fulfilling both discussing and sharing steps. Lastly, the awards mechanism allows reacting in a simple and fast way to other users’ news-related content, fulfilling the react step of the reader’s journey. In all, these mechanisms enable building a relationship of experience within the news platform, and thus increasing the readers’ engagement, involvement and immersion in the content.

3.2.2. Interviews with News’ Representatives

A semi-structured interview was conducted with six news representatives from major Portuguese news players—Público, Jornal de Notícias, SIC and Rádio Renascença. A set of eight questions, divided into two moments ((i) ice breaking questions and (ii) data collection questions), was posed relative to the impact of the journalism’s digitalization, the metrics used to evaluate the success of a news item and the interviewees’ opinion regarding the gamification strategy designed. The key purpose was to assess their perspective on the digitalization impact on journalism and to validate and obtain a new perspective on the designed prototype.

In regard to the question, What challenges did you have to face with the shift from the news’ paradigm to digital and online?, it was possible to identify the impacts that the shift to an online world had on journalism. Besides “gamification, data journalism, [and] virtual reality” (Interviewee 6), Interviewee 4 emphasizes an opinion that is shared by all interviewees: “the foundation is always the same” and “journalism is journalism, and we are always repeating that, reminding ourselves of it because it is convenient not to lose sight of what guides us, and which should always guide and enlighten us in production” (Interviewee 6).

Moreover, the NVivo software was used to facilitate the process of coding and analyzing interviewees’ answers. Following the analysis of the six conducted interviews, a total of 17 codes were identified, which were divided by 5 top-level codes—i.e., engagement techniques, teams, gamification, journalism and gamification prototype. The first top-level code—i.e., engagement techniques—allowed the analysis of the question What metrics do you use to evaluate the success of online news?, particularly relevant in the construction of a gamification system, especially one that includes a leaderboard. By using the NVivo tool word frequency, it was possible to identify the most important metrics: time (on the page), likes, views, clicks, visits and scroll.

Next, the gamification proposal was presented through a few presentation slides, and the elements that compose the proposed gamification system were shown and explained. After concluding the presentation and posing the question, In your opinion, how can the proposed strategies foster the participation of different publics/readers?, by individually pre-analyzing each of the responses, it is possible to outline the main contributions. Interviewee 2 stated that it is “a service to people that is fun, appealing, interesting, and, above all, informative”. Moreover, Interviewee 6 emphasized “the question of rewarding people, of being involved, of feeling that they are recognized for, is very interesting”, and Interviewee 1 reinforced the questions associated to level saturation, and, despite “the platform provides something special for those who reach certain points”, they mentioned being important to give special awards—“either the platform provides something special for those who reach certain points, or partnerships that the platform has”, as defined and foreseen by Potze (2018).

Overall, it was possible to extract positive feedback that corroborated the designed prototype of the gamification system and added relevant contributions that were later introduced to the prototype, such as the external rewards. Therefore, an external reward system was included, opening the opportunity to establish partnerships with other projects and companies that can offer gifts to miOne’s users, e.g., a monthly subscription to a newspaper.

3.3. Step 3—Implementation and Evaluation

After implementing the designed gamification prototype, in the context of the miOne online community, online evaluation tests were performed with a convenience sample of 11 adult learners from the Universities of the Third Age partners with the research project SEDUCE 2.0.

The next section describes the procedures taken to conduct the mentioned evaluation.

Evaluation with Older Adults from Universities of the Third Age

The online evaluation with older adults from Portuguese UTA took place from 25 November of 2020 to 11 December of 2020. Before performing any test on the miOne’s news platform, a set of questions was applied to further demographically characterize the sample and assess its access to the Internet and news consumption habits.

The average age of the sample is approximately 67 years old (minimum = 54; maximum = 75; SD = 6.788), and around 64% (n = 7) of the participants are female, whereas 36% (n = 4) are male. Similar to what was verified in the results of Step 1, send and read emails (90.91%; n = 10) and access social media (90.91%; n = 10) are the most preferred activities when accessing the Internet, followed by online search (72.73% n = 8) and read online news (63.64%; n = 7).

The prototype evaluation tests followed the structure defined in the reader’s journey, see Figure 2. Therefore, each of the activities aimed to progressively and respectively target the defined steps—i.e., read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience—while promoting participants’ community involvement and developing their engagement toward the news platform. Table 4 describes the activities expected to be performed during the evaluation test for every state of the reader’s journey. For this purpose, the levels and missions’ mechanism were used to guide the participants. Each participant joined a level with four missions to be completed, while covering all the activities defined on Table 4: (i) Keep up with the latest news—to guide participants to the news platform, (ii) Give and receive awards—to encourage participants to use the awards mechanism, (iii) Some news are worth sharing—to stimulate the news sharing and (iv) Show your opinion—to incite the debate.

Table 4.

Activities to be performed during the evaluation test. Retrieved from Gamifying News for the miOne Online Community (Regalado 2021).

At the end of the test, an oral semi-structured interview was applied to validate the gamification proposal and assess the possible impact the strategy would have on the perception of the miOne’s news platform and future engagement with it. The following questions were posed: (i) How long do you think this activity took? (ii) To what extent did this experience increase or not the interest in reading the news? What about reacting (awarding/recommendation of news)? What about sharing/discussing news? What about your relationship with the news? (iii) What did you like most about this activity? and (iv) After this experience, do you recommend using miOne’s news platform? During all the evaluation, participants were encouraged to provide additional comments.

3.4. Data Collection and Analyzing Procedures

Data triangulation from the different data sources—i.e., pre-assessment survey, interviews, field notes and participant observation—was performed in order to assure the validity of the research. In order to analyze the data collected during Step 1, i.e., quantitative data, the SPSS software was used. The remaining data was codified and analyzed using NVivo. The data collected at each step was crucial to define the steps that followed, with a close interconnection between all the data sources.

3.5. Ethical Considerations

This is study safeguards to follow the Ethics and Deontology Council of the University of Aveiro Ethical Approval for the SEDUCE 2.0 project—use of communication and information in the miOne online community by senior citizens (Project nr. POCI-0145-FEDER-031696). Moreover, all the participants signed a written informed consent before participation, stating that (i) they agree to participate voluntarily in the research, (ii) they were informed of the procedures and understood the conditions of participation in the ongoing research, (iii) they authorize the recording and capture of images and audio for research purposes and (iv) they authorize to be contacted via e-mail by the responsible researcher for the purposes of the research.

4. Results

During the period of time the tests were conducted at Step 3—i.e., from 25 November of 2020 to 11 December of 2020—it was possible to register great participation and adhesion to the gamification strategy, to the news platform and to what is still an embryonic online community. Therefore, a total of 110 awards were assigned, 46 news items were shared, and 66 news activities were published.

In order to analyze what motivated these numbers, an analysis based on the reader’s journey will be made, divided by each level, cf. Figure 2, and based on the activities proposed on Table 4.

4.1. Reading

When participants were asked to read a news item—through the mission Keep up with the latest news, all of them preferred to read it through the news platform, bypassing the newsfeed. During the observation process, a distinction was made regarding the origin of the news items read. It is possible to conclude that half (50%; n = 13) of the news read was from the news platforms’ global page, i.e., a page where all the news items shared are listed and divided by categories. Nevertheless, 34.60% (n = 9) of the news read was from the leaderboard, thus highlighting the impact this mechanism has in providing relevant and discussed news to the community. The remaining 15.40% (n = 4) concerns recent news, i.e., those that are displayed at the global page’s top.

4.2. Reacting

Reacting is the second step of the reader’s journey and, to do so, participants were incited to use the newly designed awards mechanism through the mission Give and receive awards. During the process of selecting an award, reading its meaning and assigning it to the news activity, it was possible to observe that participants valued more the person to whom they were assigning it. Participant 1, after assigning an award to an activity, stated “that’s it, she’ll be happy”, and, similarly, Participant 4 mentioned “for her to be happy (…), because she deserves it”. Therefore, considering this thoughtfulness towards the other, it is quite evident the social and recognition sides throughout this process—participants recognize the value each award has and are willing to give it to those who are close to them. Moreover, awards act as an external stimulus, as it activates “people’s curiosity, (…) of wanting to develop more. To enter more, to see beyond the award, the person is satisfied and (…), with the continuation, will want to be more updated in relation to the news here [miOne]” (Participant 5).

Lastly, it was possible to examine the awards with a larger number of endorsements. The ones with an immediate interpretation by just analyzing its visual representation, and more similar to the reactions used in other social media contexts, were the most endorsed—Super favorite (n = 28), Five stars (n = 18) and Bravo (n = 14). Equally, awards with more difficult interpretations have led them to be less used, as is the case of the awards Oh, oh… How spicy! (n = 2), So much for the denture (n = 1) and What a catch! (n = 1).

4.3. Sharing and Discussing

During the sharing and discussing steps, the levels mechanism, through the missions Some news are worth sharing and Show your opinion, encouraged participants to share news items and show their opinion using the comments section in each news activity.

Similar to the reading step, an analysis based on the source of news discussions was made. The primary source is the leaderboard, having been verified that 36.40% (n = 4) of the comments made during this evaluation process was through this gamification mechanism. The second and third main sources of discussion during the tests, each with 27.30% (n = 3), are the global news and the most recent ones. Lastly, according to the participants’ feedback, only one news item was commented on because it was the most awarded. In conclusion, the leaderboard played an essential role in leading people to comment on the news.

Moreover, a pattern was registered where the news items with the most interactions—i.e., comments and shares—were also the most awarded ones.

4.4. Relating

The clear identification of who posted each news activity is possible in the leaderboard, in the debate area and in the newsfeed, where all kinds of activities, news-related or not, are aggregated. Therefore, this clear identification of the content’s producer stimulated the engagement with news activities. Regarding this matter, Participant 2 stated that “I think it increases the interest because we know who are the people interested in the same news as well”.

The majority of the participants—i.e., Participants 1, 2, 4, 6, 7, 8 and 9—clearly identified their activities in the debate area, comparing to those shared by other users. Likewise, the leaderboard also allowed this association, as 8 out of the 11 participants identified their or other users’ news activities displayed there.

At the end of the tests, participants were asked how long they thought the activity had taken. Most of the participants had the perception that time passed faster than reality, suggesting a possible state of flow—i.e., a balance between boredom and anxiety—leading users to lose track of space and time (Zichermann and Cunningham 2011). Moreover, the participants’ opinion regarding the gamification system was coded using NVivo, resulting in one top-level code, i.e., gamification opinion. When analyzing participants’ most uttered words regarding what extent did the experience increase or not their interest in reading, reacting, awarding, sharing and discussing news, it was observed that the word ‘interesting’ was mentioned twelve times.

In addition to the participants 1 and 8 considering the miOne’s news platform a reliable source of information, they all said they would recommend its use. These are some of their statements regarding the gamification experience:

“I find it interesting because it makes me develop more knowledge. We have steps to follow, etc. I find it interesting the way it presents itself. It’s also very basic—just to say that you’ve passed the level and so on. But it’s funny the way you develop the issues in a way that… I think it’s interesting!”.—Participant 4

“It activates people’s curiosity and enthusiasm to continue using”.—Participant 5

“It’s a good strategy because if we don’t get feedback from what we communicate, we stop communicating. Either we have a very firm, principled and independent personality from others, or we give up. It’s not only those who publish that stop publishing, those who read also stop reading if there isn’t this challenge. It is of both parts. Of course, it is more painful for those who publish and have no return”.—Participant 9

Besides the questions asked, monitoring users’ activities was performed after the evaluation. From the end of all tests (4 December of 2020) to December 11th of 2020, eight participants returned to the platform and interacted somehow with its content. Chosen by six participants, assigning awards was the most popular form of interaction, possibly because they are a faster, easier and a more immediate way of reacting. Additionally, comments were the second most performed activity, leaving to last the news sharing, which involves more time, thought and social exposure of participants.

Lastly, some behavioral change was reported. In fact, only Participant 5 mentioned discussing and sharing news, and Participants 2 and 5 were the only ones who mentioned reacting to the news. Thus, it is possible to perceive the impact that the gamification system had in promoting the interaction with miOne’s news platform.

5. Discussion

This paper has presented the complete process of conception, design, implementation and evaluation of a gamification system for the news platform of an online community that targets older adults—miOne.

Step 1 had significant contributions to the gamification system in question. According to the Pew Research Center (2019), the technologies used to communicate have been growing at a vertiginous pace, and this interpersonal communication, while allowing to overcome loneliness, is something that older adults value much (Leist 2013). This fact is supported by the results of the most valued activities by the sample’s older adults: (i) activity in groups, (ii) the frequency with which they talk to other people in the community, (iii) debate news, (iv) share news and (v) react to the news. These results suggest that older adults are focused on connecting with each other—a consequence of social media, which provides benefits such as social support to older adults (Nimrod 2014)—and value sharing their opinions and thoughts—i.e., self-expression, which is fundamental to develop a sense of growth, change, openness and self-revelation (Nimrod 2014).

Based on the presented contributions of Step 1, during Step 2, the prototype was designed and presented to experts in the news area, allowing their mostly positive feedback to be collected and some minor changes to the prototype to be made. These included the addition of external rewards to the platform, reinforcing what Potze (2018) stated: rewards must have a meaning and relatedness on daily life, while translating the time and effort spent on the gamified task. This aspect was later added to the levels mechanism, enabling users to be given an external reward once a given task was completed.

Lastly, the evaluation sessions with older adult learners from Universities of the Third Age partners of the project SEDUCE 2.0, allowed us to collect some indicators that seem to point out that this gamification system can induce behavioral engagement with the miOne’s news platform by (i) allowing the clear identification of the content producers; (ii) rewarding and recognizing each user individually; (iii) simplifying the navigation within the platform, thus overcoming technological difficulties; (iv) providing external motivations for something common for them; and (v) stimulating learning and exploration of new areas, something that proved to be highly valued by them.

Thus, as already mentioned, and to add to previous studies (Altmeyer et al. 2018; Moser et al. 2015; Sotirakou and Mourlas 2015), this gamification system is one more proof that gamification can promote engagement. It was possible to overcome some barriers that older adults face with ICT (e.g., intrapersonal—being too old to use; interpersonal—not having someone to teach them how to use (Leist 2013), or the perceived need to use technology (Fisk et al. 2009)) and deliver a pleasant and user-friendly solution that not only brought more involvement but also proved to be a lively, enjoyable and emerging experience. Thus, not only it is possible to increase older adults’ technological prowess but also sustain their psychological and social activities (Altmeyer et al. 2018; Gerling and Masuch 2011), contributing to their overall well-being and self-esteem (Ijsselsteijn et al. 2007; Ryan et al. 2006).

Furthermore, the ethical aspects of this gamification system should not be neglected. Its goal, as previously mentioned, is to improve reader’s experience, increase engagement and surpass possible technological barriers. In fact, we were able to prove that the designed and implemented gamification system is able to engage older adults with miOne’s online news. However, caution must be applied when adopting gamification systems to online news, especially in the context of an online community, as it may also encourage and stimulate the ongoing spread of misinformation, clickbait news titles that mislead readers and fake news, and promote an echo chamber of thoughts, i.e., the formation of homogeneous groups that limit and reinforce a shared narrative among all its users (Cinelli et al. 2021; Törnberg 2018).

Therefore, it is crucial to find strategies to mitigate such misinformation and polarization, being essential to analyze the structure of the context where the gamification strategy will be applied. As highlighted by Cinelli and colleagues (Cinelli et al. 2021), social media feeds without an adjustable algorithm by its users (e.g., Facebook and Twitter) promote higher segregation of news consumption than in those where this is possible (e.g., Reddit). Therefore, the spread of fake news is a by-product of the profitable and engaging algorithms (Rhodes 2021). Furthermore, according to Garrett (2009), in the particular case of politics, the longer users are exposed to opinion-challenging information, the more they are willing to maintain awareness of the heterogeneous political space.

Moreover, Zichermann (2019) proposes a gamified solution to stop the spread of fake news based on a trust score and an up- and down-vote system. Calculated from the variables of credibility of the originator, credibility of the amplifiers, partisanship and velocity, the author believes that transparency is the key, enabling the construction of reference check as a social proof (Zichermann 2019).

Lastly, it is important to acknowledge that the gamification system resulting from this research focuses on the model for onboarding a reader’s 6-step journey (read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience) within the context of a Senior Online Community, (cf. Figure 2). Therefore, although there is a component of content relatedness (one of the reader’s journey steps which is achieved by the clear identification of the news activities’ authors, and through the leaderboard), the main goal of this research was to design a gamification system for the Senior Online Community’s news platform and assess it regarding its ability to behaviorally engage older adults.

6. Conclusions

In a nutshell, this study allowed to further extend current knowledge on gamification solutions to news platforms targeting older adults, the relationship established between the aged population and news consumption habits, as well as their familiarity with gamification mechanisms.

The designed and implemented gamification strategy for the miOne’s news platform has two major differentiator aspects: (i) a common reward engine, with no disconnection between its elements, and thus facilitating its understanding; and (ii) a prototyped solution that took the context of use and the added difficulties presented by older adult learners. While other apps fail in the considerations needed to develop technological solutions for the aging citizen, and that the development of gamification strategies do not have them in mind, the solution presented in this paper fills this gap. One may wonder, why gamify news for an audience that is most interested in online news. In fact, despite the high consumption of news, the technical difficulties are still not completely surpassed. Thus, the gamification can be a strategy for learning and motivating continued consumption of online news. Moreover, we make the following contributions for gamification and journalism for aging audiences research: (i) a prototype that socially gamifies news to support aging readers’ experience and (ii) a model for a reader’s 6-step journey (read, react, discuss, share, relate and experience) to onboard within the context of a Senior Online Community using gamification.

A number of limitations should be considered, and the results need to be interpreted with caution. Firstly, the topic of gamification and digital media in the context of an aging population is, still, to the best of our knowledge, an unexplored topic, being this is pioneering research. Secondly, a convenience sample was used. So, attempts to generalize beyond these participants are discouraged. Thirdly, during the course of this research process, the world was facing the COVID-19 outbreak. Due to the fact of older adults having a greater risk of developing serious complications with the COVID-19 disease, the face-to-face contact with the students from the Universities of the Third Age was highly limited. Consequently, the evaluation tests had to be performed online, making it difficult to recruit participants and monitor tests.

Regarding further work, a social network analysis (SNA) could be performed, allowing further knowledge on users’ behaviors and engagement patterns (Ferreira 2016; De Nooy et al. 2018), and the efficiency of the outlined gamification strategy proposed could be deduced. Due to time constraints and the embryonic state of the miOne online community, it would not be possible to collect relevant data. Moreover, a larger sample could be used in further research, allowing a more confirmatory approach. Lastly, the gamification system could incorporate a content validation mechanism to mitigate misinformation and the possible spreading of fake news, thereby not only focusing on the achieved engagement.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.R. and L.V.C.; methodology, F.R., L.V.C. and A.I.V.; software, F.R. and L.V.C.; validation, F.R., L.V.C. and A.I.V.; formal analysis, F.R. and L.V.C.; investigation, F.R. and L.V.C.; resources, L.V.C. and A.I.V.; data curation, F.R. and L.V.C.; writing—original draft preparation, F.R. and L.V.C.; writing—review and editing, F.R., L.V.C., F.M., and A.I.V.; visualization, F.R. and L.V.C.; supervision, L.V.C. and A.I.V.; project administration, A.I.V.; funding acquisition, L.V.C., F.M., and A.I.V. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by FCT and COMPETE 2020, Portugal 2020 and European Union, European Regional Development Fund, SEDUCE 2.0 project nr. POCI-0145-FEDER-031696.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Ethics and Deontology Council of University of Aveiro (ResolutionNo 12-CED, 13 November 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated from the questionnaire and interviews during the current study are not publicly available following the General Data Protection Regulation but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the SEDUCE 2.0 research project—Use of Communication and Information in the online community miOne by senior citizens, and with financial support from FCT and COMPETE 2020, Portugal 2020 and European Union, European Regional Development Fund, SEDUCE 2.0 project nr. POCI-0145-FEDER-031696. We would also like to thank the DigiMedia research unit—DIGIMEDIA (UIDP/05460/2020+UIBD/05460/2020).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | Available online: https://www.stitch.net/ (accessed on 29 May 2021). |

| 2 | Available online: https://www.olderiswiser.com/ (accessed on 29 May 2021). |

| 3 | Available online: https://www.buzz50.com/ (accessed on 29 May 2021). |

| 4 | Available online: https://mione.altice.pt/ (accessed on 29 May 2021). |

| 5 | Available online: https://www.reddit.com/ (accessed on 28 January 2021). |

| 6 | Available online: https://campus.altice.pt/ (accessed on 3 May 2021). |

| 7 | Available online: https://pt-pt.khanacademy.org/ (accessed on 3 May 2021). |

| 8 | Available online: https://peoople.app/ (accessed on 28 January 2021). |

| 9 | Available online: https://www.reddithelp.com/hc/en-us/articles/360043034132 (accessed on 28 January 2021). |

| 10 | Available online: https://www.reddit.com/coins (accessed on 3 May 2021). |

| 11 | Universities of the Third Age (UTA) are institutions dedicated to the occupation of their students’ free time, through a variety of theoretical and/or practical learning topics—e.g., informatics, sewing, theater, singing, and dancing. Their target audience, which is also the one of miOne online community—the context within which this study is being developed, is adults aged 50 and older. |

References

- Altmeyer, Maximilian, Pascal Lessel, and Antonio Krüger. 2018. Investigating gamification for seniors aged 75+. Paper presented at 2018 on Designing Interactive Systems Conference (DIS ’18), Hong Kong, China, June 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Araújo, Inês, Luís Pedro, Carlos Santos, and João Batista. 2017. Crachás: Como usar em contexto educativo? In Conference: Challenges 2017: Aprender nas Nuvens, Learning in the Clouds. Braga: Universidade do Minho, pp. 157–74. [Google Scholar]

- Barambones, Jose, Ali Abavisani, Elena Villalba Mora, Miguel Gomez-Hernandez, and Xavier Ferré. 2020. Discussing on Gamification for Elderly Literature, Motivation and Adherence. Paper presented at the 6th International Conference on Information and Communication Technologies for Ageing Well and E-Health (ICT4AWE 2020), Prague, Czech Republic, May 3–5; pp. 308–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes, Renee. 2015. Digital news and silver surfers an examination of older Australians engagement with news online. Journal of Telecommunications and the Digital Economy 3: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, A. 2020. Exploring digital divides in older adults’ news consumption. Nordicom Review 41: 163–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, Sanat Kumar, Surya Nepal, Nathalie Colineau, and Cecile Paris. 2012. Using gamification in an online community. In CollaborateCom 2012—Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Collaborative Computing: Networking, Applications and Worksharing. Pittsburgh: IEEE, pp. 611–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bista, Sanat Kumar, Surya Nepal, Nathalie Colineau, and Cecile Paris. 2014. Gamification for online communities: A case study for delivering government services. International Journal of Cooperative Information Systems 23: 1441002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boot, Walter R., Dustin Souders, Neil Charness, Kenneth Blocker, Nelson Roque, and Thomas Vitale. 2016. The gamification of cognitive training: Older adults’ perceptions of and attitudes toward digital game-based interventions. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (including subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Cham: Springer, vol. 9754, pp. 290–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brashier, Nadia M., and Daniel L. Schacter. 2020. Aging in an Era of Fake News. Current Directions in Psychological Science 29: 316–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caldwell, Cath, and Yolanda Zappaterra. 2014. Editorial Design: Digital and Print. London: Laurence King Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Cavusoglu, Huseyin, Zhuolun Li, and Ke-Wei Huang. 2015. Can gamification motivate voluntary contributions? The case of StackOverflow Q&A community. Paper presented at the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, Vancouver, BC, Canada, March 14–18; New York: Association for Computing Machinery, vol. 2015, pp. 171–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, Vanessa, António Coelho, and Valentina Nisi. 2017. Enhancing Museums’ Experiences Through Games and Stories for Young Audiences. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Cham: Springer, vol. 10690, pp. 351–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinelli, Matteo, Gianmarco De Francisci Morales, Alessandro Galeazzi, Walter Quattrociocchi, and Michele Starnini. 2021. The echo chamber effect on social media. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conill, Raul Ferrer. 2016. Points, badges, and news. A study of the introduction of gamification into journalism practice. Comunicació: Revista de Recerca i Anàlisi 33: 45–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conill, Raul Ferrer, and Michael Karlsson. 2015. The gamification of journalism. In Emerging Research and Trends in Gamification. Edited by Donna Davis and Harsha Gangadharbatia. Pennsylvania: IGI Global, pp. 356–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordero-Brito, Staling, and Juanjo Mena. 2018. Gamification in the Social Environment: A tool for Motivation and Engagement. Paper presented at the Sixth International Conference on Technological Ecosystems for Enhancing Multiculturality, Salamanca, Spain, October 24–26; New York: ACM. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Nooy, Wouter, Andrej Mrvar, and Vladimir Batagelj. 2018. Exploratory Social Network Analysis with Pajek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vette, Frederiek, Monique Tabak, Hermie J. Hermens, and M. Vollenbroek. 2018. Mapping game preferences of older adults: A field study towards tailored gamified applications. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deterding, Sebastian, Dan Dixon, Rilla Khaled, and Lennart Nacke. 2011. From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining ‘gamification’. Paper presented at the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments, MindTrek 2011, Tampere, Finland, September 28–30; pp. 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte-Hueros, Ana, Carmen Yot-Domínguez, and Ángeles Merino-Godoy. 2020. Healthy Jeart. Developing an app to promote health among young people. Education and Information Technologies 25: 1837–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, Maria de Fatima Gomes Pais. 2016. SAPO Campus: Aprendizagem, Ensino e Pessoas em Rede. Ph.D. thesis, Universidade de Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/15855 (accessed on 13 February 2021).

- Fisher, Caroline, Sora Park, Jee Young Lee, Kate Holland, and Emma John. 2021. Older people’s news dependency and social connectedness. Media International Australia 181: 183–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisk, Arthur D., Sara J. Czaja, Wendy A. Rogers, Neil Charness, and Joseph Sharit. 2009. Designing for Older Adults: Principles and Creative Human Factors Approaches, 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foxman, Maxwell Henry. 2015. Play the News: Fun and Games in Digital Journalism. New York: Tow Center for Digital Journalism, Columbia University, August. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrett, R. Kelly. 2009. Echo chambers online?: Politically motivated selective exposure among Internet news users. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 14: 265–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, Kathrin M., and Maic Masuch. 2011. Exploring the Potential of Gamification Among Frail Elderly Persons. Paper presented at the CHI 2011 Workshop Gamification: Using Game Design Elements in Non-Game Contexts, Vancouver, BC, Canada, May 7–12; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Guardia, Juan José, José Luis Del Olmo, Iván Roa, and Vanesa Berlanga. 2019. Innovation in the teaching-learning process: The case of Kahoot! On the Horizon 27: 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huffington, Arianna. 2010. Introducing HuffPost Badges: Taking Our Community to the Next Level|HuffPost. Available online: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/introducing-huffpost-badg_b_557168 (accessed on 13 February 2020).

- Ijsselsteijn, Wijnand, Henk Herman Nap, Yvonne de Kort, and Karolien Poels. 2007. Digital game design for elderly users. Paper presented at the 2007 Conference on Future Play, Future Play ’07, Toronto, ON, Canada, November 14–17; pp. 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Julie, and Nathan Altadonna. 2012. We don’t need no stinkin’ badges: Examining the social role of badges in the Huffington post. Paper presented at the ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, CSCW, Seattle, WA, USA, February 11–15; pp. 249–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappen, Dennis L. 2015. Adaptive engagement of older adults’ fitness through gamification. In CHI PLAY 2015—Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc., pp. 403–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappen, Dennis, Pejman Mirza-Babaei, and Lennart Nacke. 2018. Gamification of Older Adults’ Physical Activity: An Eight-Week Study. Paper presented at the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Hilton Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, January 3–6; Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10125/50036 (accessed on 1 November 2021).

- Kazhamiakin, Raman, Annapaola Marconi, Alberto Martinelli, Marco Pistore, and Giuseppe Valetto. 2016. A gamification framework for the long-term engagement of smart citizens. In IEEE 2nd International Smart Cities Conference: Improving the Citizens Quality of Life, ISC2 2016—Proceedings. Trento: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, Jonna, and Aqdas Malik. 2020. Gamification for Older Adults: A Systematic Literature Review. The Gerontologist 61: e360–e372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koivisto, Jonna, and Juho Hamari. 2014. Demographic differences in perceived benefits from gamification. Computers in Human Behavior 35: 179–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostopoulos, Panagiotis, Athanasios I. Kyritsis, Vincent Ricard, Michel Deriaz, and Dimitri Konstantas. 2018. Enhance daily live and health of elderly people. In Procedia Computer Science. Amsterdam: Elsevier B.V., vol. 130, pp. 967–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Bob, Yiwei Chen, and Lynne Hewitt. 2011. Age differences in constraints encountered by seniors in their use of computers and the internet. Computers in Human Behavior 27: 1231–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Sang Bum, Jae Hun Oh, Jeong Ho Park, Seung Pill Choi, and Jung Hee Wee. 2018. Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clinical and Experimental Emergency Medicine 5: 249–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leist, Anja K. 2013. Social media use of older adults: A mini-review. Gerontology 59: 378–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Weijane, Hui-Chun Lin, and Hsiu-Ping Yueh. 2014. Explore elder users’ reading behaviors with online newspaper. In Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics). Cham: Springer, vol. 8528, pp. 184–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manders-Huits, Noëmi. 2011. What Values in Design? The Challenge of Incorporating Moral Values into Design. Science and Engineering Ethics 17: 271–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martinho, Diogo, João Carneiro, Juan M. Corchado, and Goreti Marreiros. 2020. A systematic review of gamification techniques applied to elderly care. Artificial Intelligence Review 53: 4863–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Méndez, Juana Isabel, Omar Mata, Pedro Ponce, Alan Meier, Therese Peffer, and Arturo Molina. 2020. Multi-sensor System, Gamification, and Artificial Intelligence for Benefit Elderly People. In Studies in Systems, Decision and Control. Cham: Springer, vol. 273, pp. 207–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micallef, Nicholas, Mihai Avram, Filippo Menczer, and Sameer Patil. 2021. Fakey: A Game Intervention to Improve News Literacy on Social Media. Paper presented at the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 5 (CSCW1), New York, NY, USA, April 13. [Google Scholar]

- Minge, Michael, and Dietlind Helene Cymek. 2020. Investigating the potential of gamification to improve seniors’ experience and use of technology. Information 11: 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrison, Donn, and Conor Hayes. 2013. Here, have an upvote: Communication behaviour and karma on Reddit. In INFORMATIK 2013—Informatik angepasst an Mensch, Organisation und Umwelt. Bonn: Gesellschaft für Informatik e.V., vol. 220, pp. 2258–68. [Google Scholar]

- Moser, Christiane, Michaela Peterhansl, Thomas Kargl, and Manfred Tscheligi. 2015. The potentials of gamification to motivate older adults to participate in a P2P support exchange platform. In CHI PLAY 2015—Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, Inc., pp. 655–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, Galit. 2010. Seniors’ online communities: A quantitative content analysis. Gerontologist 50: 382–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nimrod, Galit. 2014. The benefits of and constraints to participation in seniors’ online communities. Leisure Studies 33: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, Lia Raquel. 2006. Metodologia do desenvolvimento: Um estudo de criação de um ambiente de e-learning para o ensino presencial universitário. Educação Unisinos 10: 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, Richard, and Anne McLaughlin. 2011. Designing Displays for Older Adults. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pannese, Lucia, David Wortley, and Antonio Ascolese. 2016. Gamified wellbeing for all ages—How technology and gamification can support physical and mental wellbeing in the ageing society. In IFMBE Proceedings. Cham: Springer, vol. 57, pp. 1281–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pew Research Center. 2019. Social Media Fact Sheet. Available online: https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/fact-sheet/social-media/ (accessed on 3 March 2021).

- Potze, Taco. 2018. Gamification Is Dead: A Proposal for Gamification 3.0. Available online: https://www.getopensocial.com/blog/news-room/gamification-is-dead (accessed on 19 November 2019).

- Regalado, Francisco Silva Ferreira. 2021. Gamifying News for the miOne Online Community [Master Dissertation in Multimedia Communication]. Aveiro: Universidade de Aveiro. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10773/31503 (accessed on 2 November 2021).

- Regalado, Francisco, Liliana Vale Costa, and Ana Isabel Veloso. 2021. Online News and Gamification Habits in Late Adulthood: A Survey. Lecture Notes in Computer Science (Including Subseries Lecture Notes in Artificial Intelligence and Lecture Notes in Bioinformatics), 12786 LNCS. Cham: Springer, pp. 405–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes, Samuel C. 2021. Filter Bubbles, Echo Chambers, and Fake News: How Social Media Conditions Individuals to Be Less Critical of Political Misinformation. Political Communication, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, Richard M., C. Scott Rigby, and Andrew Przybylski. 2006. The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-Determination Theory Approach. Motivation and Emotion 30: 344–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, Alexander. 2020. The Digital Exclusion of Older Adults during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Journal of Gerontological Social Work 63: 674–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siapera, Eugenia, and Andreas Veglis. 2012. Introduction: The Evolution of Online Journalism. In The Handbook of Global Online Journalism. Edited by Eugenia Siapera and Andreas Veglis. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotirakou, Catherine, and Constantinos Mourlas. 2015. Designing a gamified news reader for mobile devices. Paper presented at the 2015 International Conference on Interactive Mobile Communication Technologies and Learning, IMCL 2015, Thessaloniki, Greece, November 19–20; Thousand Oaks: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., pp. 332–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Törnberg, Petter. 2018. Echo chambers and viral misinformation: Modeling fake news as complex contagion. PLoS ONE 13: e0203958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toscani, Carolina, Daniel Gery, Igor Steinmacher, and Sabrina Marczak. 2018. A gamification proposal to support the onboarding of newcomers in the flosscoach portal. In ACM International Conference Proceeding Series. New York: Association for Computing Machinery, vol. 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Treanor, Mike, and Michael Mateas. 2009. Newsgames: Procedural rhetoric meets political cartoons. In Breaking New Ground: Innovation in Games, Play, Practice and Theory—Proceedings of DiGRA 2009. Uxbridge: Brunel University, vol. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Maren, Jean Marie. 2004. Méthodes de Recherche pour L’éducation. Éducation Formation. Fondements. Montréal: Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal and DeBoeck Université. [Google Scholar]

- WHO—World Health Organization. 2002. Active Ageing: A Policy Framework. A Contribution of World Health Organization to the Second United Nations World Assembly of Ageing. Madrid: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zichermann, Gabe. 2019. How Gamification Can Beat Fake News. Available online: https://www.gamification.co/2019/07/09/how-gamification-can-beat-fake-news/ (accessed on 4 January 2020).

- Zichermann, Gabe, and Christopher Cunningham. 2011. Gamification by Design: Implementing Game Mechanics in Web and Mobile Apps, 1st ed. Sebastopol: O’Reilly Media, Inc. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).