Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Different Groups and Different Places—A Critical-Realist Conception

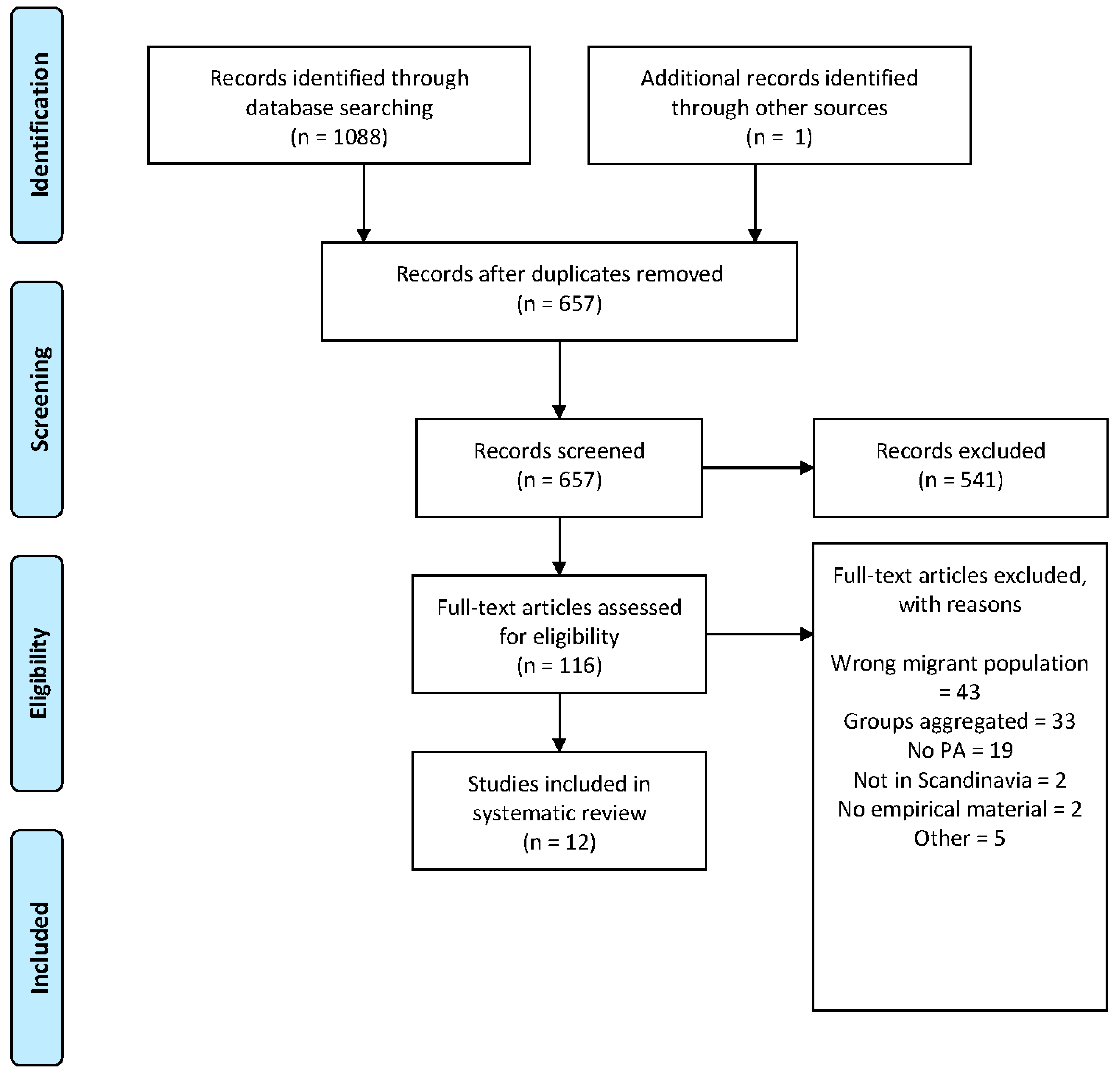

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Inclusion Criteria

2.2. Exclusion

2.3. Search Strategy

TITLE-ABS-KEY (migration* OR integration* OR acculturation* OR assimilation* OR segregation* OR migrants* OR immigrants* AND sport* OR leisure* OR “physical activity*” OR exercise* AND Sweden* OR Norway* OR Denmark* OR Finland* OR Iceland* OR Scandinavia* OR nordic*)

3. Results

3.1. Post-Socialist Migrants’ Health and Levels of Physical Activity

3.2. Nordic Nature and Climate as Both an Opportunity and Barrier

When I walk along the river, I am breathing fresh air, and [...] thinking [...] just positive! [laughter] It is very good for my health and for my body and for how I feel. [...] When I came to Norway, at first, I sat at home and tried to read something but did not understand [...] tried to watch television, did not understand. It was a very difficult period! But, afterwards, I came to nature. Nature helped me! Today, I feel very good, but last year I was so sad because I did not have friends, no Norwegian friends, no family, and I was alone at home [...] but nature helped me!

3.3. Mental Health Benefits and Barriers

3.4. Previous Sport Experience

3.5. Language

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adebayo, Folasade A., Suvi T. Itkonen, Eero Lilja, Tuija Jääskeläinen, Annamari Lundqvist, Tiina Laatikainen, Päivikki Koponen, Kevin D. Cashman, Maijaliisa Erkkola, and Christel Lamberg-Allardt. 2020. Prevalence and Determinants of Vitamin D Deficiency and Insufficiency among Three Immigrant Groups in Finland: Evidence from a Population-Based Study Using Standardised 25-HydroxyVitamin D Data. Public Health Nutrition 23: 1254–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ager, Alastair, and Alison Strang. 2008. Understanding Integration: A Conceptual Framework. Journal of Refugee Studies 21: 166–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Archer, Margaret Scotford. 1995. Realist Social Theory: The Morphogenetic Approach. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Archer, Margaret Scotford. 2003. Structure, Agency and the Internal Conversation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Badiu, Denisa L., Diana A. Onose, Mihai R. Niță, and Raffaele Lafortezza. 2019. From ‘Red’ to Green? A Look into the Evolution of Green Spaces in a Post-Socialist City. Landscape and Urban Planning 187: 156–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakewell, Oliver. 2010. Some Reflections on Structure and Agency in Migration Theory. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 36: 1689–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Beery, Thomas H. 2013. Nordic in Nature: Friluftsliv and Environmental Connectedness. Environmental Education Research 19: 94–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berghöfer, Anne, Tobias Pischon, Thomas Reinhold, Caroline M. Apovian, Arya M. Sharma, and Stefan N. Willich. 2008. Obesity Prevalence from a European Perspective: A Systematic Review. BMC Public Health 8: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Berry, John W. 2005. Acculturation: Living Successfully in Two Cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations 29: 697–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biernat, Elżbieta, and Sonia Buchholtz. 2016. The Regularities in Insufficient Leisure-Time Physical Activity in Poland. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 13: 798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bronikowska, Małgorzata, Michał Bronikowski, and Nadja Schott. 2011. You Think You Are Too Old to Play? Playing Games and Aging. Human Movement 12: 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camacho, Terry C., Robert E. Roberts, Nancy B. Lazarus, George A. Kaplan, and Richard D. Cohen. 1991. Physical Activity and Depression: Evidence from the Alameda County Study. American Journal of Epidemiology 134: 220–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caperchione, Cristina M., Gregory S. Kolt, and W. Kerry Mummery. 2009. Physical Activity in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse Migrant Groups to Western Society: A Review of Barriers, Enablers and Experiences. Sports Medicine. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlsson, Axel C., Per Wändell, Ulf Riserus, Johan Ärnlöv, Yan Borné, Gunnar Engström, Karin Leander, Bruna Gigante, Mai Lis Hellénius, and Ulf de Faire. 2014. Differences in Anthropometric Measures in Immigrants and Swedish-Born Individuals: Results from Two Community-Based Cohort Studies. Preventive Medicine 69: 151–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czapka, Elżbieta. 2012. The Health of New Labour Migrants: Polish Migrants in Norway. In Health Inequalities and Risk Factors among Migrants and Ethnic Minorities. Antwerp: Garant, vol. 1, pp. 62–150. [Google Scholar]

- Czapka, Elżbieta Anna, and Mette Sagbakken. 2016. ‘Where to Find Those Doctors?’ A Qualitative Study on Barriers and Facilitators in Access to and Utilization of Health Care Services by Polish Migrants in Norway. BMC Health Services Research 16: 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Danermark, Berth, Mats Ekström, and Jan Ch Karlsson. 2019. Explaining Society: Critical Realism in the Social Sciences. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- de Almeida Vieira Monteiro, Ana Paula Teixeira, and Adriano Vaz Serra. 2011. Vulnerability to Stress in Migratory Contexts: A Study with Eastern European Immigrants Residing in Portugal. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health 13: 690–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delaney, Liam, and Emily Keaney. 2005. Sport and Social Capital in the United Kingdom: Statistical Evidence from National and International Survey Data. Dublin: Economic and Social Research Instititute and Instititute for Public Policy Research 32: 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Dollman, James, and Nicole R. Lewis. 2010. The Impact of Socioeconomic Position on Sport Participation among South Australian Youth. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport 13: 318–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, Jason. 2013. Adolescent Depression and Adult Labor Market Outcomes. Southern Economic Journal 80: 26–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fränkel, Silvia, Daniela Sellmann-Risse, and Melanie Basten. 2019. Fourth Graders’ Connectedness to Nature—Does Cultural Background Matter? Journal of Environmental Psychology 66: 101347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fridberg, Torben. 2010. Sport and Exercise in Denmark, Scandinavia and Europe. Sport in Society 13: 583–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gehrmann, Sebastian, and Pamela Wicker. 2021. The Effect of Regional and Social Origin on Health-Related Sport and Physical Activity of Young People in Europe. European Journal for Sport and Society, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelter, Hans. 2000. Friluftsliv: The Scandinavian Philosophy of Outdoor Life. Canadian Journal of Environmental Education (CJEE) 5: 77–92. [Google Scholar]

- Kerkenaar, Marlies M. E., Manfred Maier, Ruth Kutalek, Antoine L. M. Lagro-Janssen, Robin Ristl, and Otto Pichlhöfer. 2013. Depression and Anxiety among Migrants in Austria: A Population Based Study of Prevalence and Utilization of Health Care Services. Journal of Affective Disorders 151: 220–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolosnitsyna, Marina G., Natalia A. Khorkina, and Marina V. Lopatina. 2020. Factors Affecting Youth Physical Activities: Evidence from Russia. Мoнитoринг Общественнoгo Мнения: Экoнoмические и Сoциальные Перемены 5: 578–601. [Google Scholar]

- Kossakowski, Radosław, Magdalena Herzberg-kurasz, and Magdalena Żadkowska. 2016. Social Pressure or Adaptation to New Cultural Patterns? Sport-Related Attitudes and Practices of Polish Migrants in Norway. In Migration and the Transmission of Cultural Patterns. Edited by Mucha Janusz. Kraków: Wydawnictwo, vol. 985, pp. 59–74. [Google Scholar]

- Krzysztoszek, Jana, Ida Laudanska-Krzeminska, and Michał Bronikowski. 2019. Assessment of Epidemiological Obesity among Adults in EU Countries. Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine 26: 341–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kylasov, Alexey V. 2019. Traditional Sports and Games along the Silk Roads. International Journal of Ethnosport and Traditional Games 1: 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, I-Min, Eric J Shiroma, Felipe Lobelo, Pekka Puska, Steven N Blair, Peter T Katzmarzyk, and Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group. 2012. Effect of Physical Inactivity on Major Non-Communicable Diseases Worldwide: An Analysis of Burden of Disease and Life Expectancy. The Lancet 380: 219–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lenneis, Verena, and Gertrud Pfister. 2016. Playing after Work? Opportunities and Challenges of a Physical Activity Programme for Female Cleaners. International Sports Studies 38: 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindström, Martin, and Jan Sundquist. 2001. Immigration and Leisure-Time Physical Inactivity: A Population-Based Study. Ethnicity and Health 6: 77–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lood, Qarin, Susanne Gustafsson, and Synneve Dahlin Ivanoff. 2015. Bridging Barriers to Health Promotion: A Feasibility Pilot Study of the ‘Promoting Aging Migrants’ Capabilities Study’. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice 21: 604–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, Catherine Anne Nicole, and Berit Viken. 2020. Immigrant Women, Nature and Mental Health. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care 16: 359–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, Catherine Anne Nicole, and Berit Viken. 2021. A Qualitative Exploration of Interactions with Natural Environments among Immigrant Women in Norway. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luszczynska, Aleksandra, Frederick X. Gibbons, Bettina F. Piko, and Mert Tekozel. 2004. Self-Regulatory Cognitions, Social Comparison, and Perceived Peers’ Behaviors as Predictors of Nutrition and Physical Activity: A Comparison among Adolescents in Hungary, Poland, Turkey, and USA. Psychology & Health 19: 577–93. [Google Scholar]

- Masri, Aymen El, Gregory S. Kolt, and Emma S. George. 2021. A Systematic Review of Qualitative Studies Exploring the Factors Influencing the Physical Activity Levels of Arab Migrants. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 18: 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mattoo, Aaditya, Ileana Cristina Neagu, and Çaǧlar Özden. 2008. Brain Waste? Educated Immigrants in the US Labor Market. Journal of Development Economics 87: 255–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Morawa, Eva, and Yesim Erim. 2015. Health-Related Quality of Life and Sense of Coherence among Polish Immigrants in Germany and Indigenous Poles. Transcultural Psychiatry 52: 376–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mrazek, Joachim, Ludmila Fialová, Natalia Rossiyskaya, and Irina Bykhovskaya. 2004. Health and Physical Activity in Central and Eastern Europe. European Journal for Sport and Society 1: 145–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngongalah, Lem, Judith Rankin, Tim Rapley, Adefisayo Odeniyi, Zainab Akhter, and Nicola Heslehurst. 2018. Dietary and Physical Activity Behaviours in African Migrant Women Living in High Income Countries: A Systematic Review and Framework Synthesis. Nutrients 10: 1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nowicka, Monika. 2016. Rejected or Transmitted Patterns? Leisure Time and Holiday Celebration: Case of Polish Immigrants in Iceland. In Migration and the Transmission of Cultural Patterns. Edited by Mucha Janusz. Kraków: Wydawnictwo, vol. 985, pp. 43–57. [Google Scholar]

- Osei-Kwasi, Hibbah Araba, Mary Nicolaou, Katie Powell, Laura Terragni, Lea Maes, Karien Stronks, Nanna Lien, and Michelle Holdsworth. 2016. Systematic Mapping Review of the Factors Influencing Dietary Behaviour in Ethnic Minority Groups Living in Europe: A DEDIPAC Study. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 13: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pavey, Toby G., Nicola W. Burton, and Wendy J. Brown. 2015. Prospective Relationships between Physical Activity and Optimism in Young and Mid-Aged Women. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 12: 915–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pawson, Ray, Trisha Greenhalgh, Gill Harvey, and Kieran Walshe. 2005. Realist Review-a New Method of Systematic Review Designed for Complex Policy Interventions. Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 10: 21–34. [Google Scholar]

- Penninx, Brenda W. J. H., Yuri Milaneschi, Femke Lamers, and Nicole Vogelzangs. 2013. Understanding the Somatic Consequences of Depression: Biological Mechanisms and the Role of Depression Symptom Profile. BMC Medicine 11: 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rebar, Amanda L., Robert Stanton, David Geard, Camille Short, Mitch J. Duncan, and Corneel Vandelanotte. 2015. A Meta-Meta-Analysis of the Effect of Physical Activity on Depression and Anxiety in Non-Clinical Adult Populations. Health Psychology Review 9: 366–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, Kyle, Laura Misener, and Dan Dubeau. 2015. ‘Community Cup, We Are a Big Family’: Examining Social Inclusion and Acculturation of Newcomers to Canada through a Participatory Sport Event. Social Inclusion 3: 129–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Riordan, James. 2009. Russia/The Soviet Union. In Routledge Companion to Sports History. New York: Routledge, pp. 557–68. [Google Scholar]

- Ronellenfitsch, Ulrich, and Oliver Razum. 2004. Deteriorating Health Satisfaction among Immigrants from Eastern Europe to Germany. International Journal for Equity in Health 3: 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ryan, Louise, Rosemary Sales, Mary Tilki, and Bernadetta Siara. 2009. Family Strategies and Transnational Migration: Recent Polish Migrants in London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 35: 61–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, Elin, Ingrid Bolmsjö, and Ellis Janzon. 2015. Attitudes to and Experiences of Physical Activity among Migrant Women from Former Yugoslavia: A Qualitative Interview Study about Physical Activity and Its Beneficial Effect on Heart Health, in Malmö, Sweden. AIMS Public Health 2: 194–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmalz, Dorothy L., Glenn D. Deane, Leann L. Birch, and Kirsten Krahnstoever Davison. 2007. A Longitudinal Assessment of the Links between Physical Activity and Self-Esteem in Early Adolescent Non-Hispanic Females. Journal of Adolescent Health 41: 559–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Skille, Eivind Å. 2011. Sport for All in Scandinavia: Sport Policy and Participation in Norway, Sweden and Denmark. International Journal of Sport Policy 3: 327–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steptoe, Andrew, and Jane Wardle. 2001. Health Behaviour, Risk Awareness and Emotional Well-Being in Students from Eastern Europe and Western Europe. Social Science & Medicine 53: 1621–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sungurova, Yulia, Sven Erik Johansson, and Jan Sundquist. 2006. East—West Health Divide and East—West Migration: Self-Reported Health of Immigrants from Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 34: 217–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaillant, Nicolas, and François-Charles Wolff. 2010. Origin Differences in Self-Reported Health among Older Migrants Living in France. Public Health 124: 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vélez-Agosto, Nicole M., José G. Soto-Crespo, Mónica Vizcarrondo-Oppenheimer, Stephanie Vega-Molina, and Cynthia García Coll. 2017. Bronfenbrenner’s Bioecological Theory Revision: Moving Culture from the Macro into the Micro. Perspectives on Psychological Science 12: 900–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venter, Zander S., David N Barton, Vegard Gundersen, Helene Figari, and Megan Nowell. 2020. Urban Nature in a Time of Crisis: Recreational Use of Green Space Increases during the COVID-19 Outbreak in Oslo, Norway. Environmental Research Letters 15: 104075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walseth, Kristin. 2016. Sport within Muslim Organizations in Norway: Ethnic Segregated Activities as Arena for Integration. Leisure Studies 35: 78–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wändell, Per Erik, Sari Ponzer, Sven-Erik Johansson, Kristina Sundquist, and Jan Sundquist. 2004. Country of Birth and Body Mass Index: A National Study of 2000 Immigrants in Sweden. European Journal of Epidemiology 19: 1005–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whittemore, Robin, and Kathleen Knafl. 2005. The Integrative Review: Updated Methodology. Journal of Advanced Nursing 52: 546–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Outcomes | Due to the embeddedness of PA in Norwegian life, Poles experience pressure to culturally adapt. This results in increased PA. | Most cleaners found the intervention too time- and energy-consuming. Our respondent of interest highlighted previous PA experience as crucial. | The respondents of interest expressed clear socio-cultural factors at play, such as different use of nature in their home country compared to Norway. | The use of nature is physically passive and relaxing instead of used as a way for physical exercise. | In the early stages, Polish migrants reject Icelandic culture and reproduce Polish leisure patterns, which entails physical inactivity. |

| Country | Norway | Denmark | Norway | Norway | Iceland |

| Sample | 37 Poles and 17 of their spouses in dyadic interviews | 20 cleaners and five supervisors, out of which one originated from Serbia | 14 female migrants out of which 2 were from Poland, 1 was from Latvia, 1 was from Russia, and 1 was from Bulgaria | Same sample as above | 71 Poles |

| Theory | Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM) | The socio-ecological model | No explicit theoretical framework adopted | Image of wilderness | Berry’s integration typology |

| Method | Individual semi-structured interviews and dyadic semi-structured interviews | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Semi-structured interviews | Semi-structured interviews | Semi-structured interviews |

| Purpose | To study the transmission of cultural patterns and adaptation through leisure | To explore challenges and opportunities in a PA program for cleaners | To examine how nature can help migrant women’s mental health | To explore interactions with nature amongst female migrants | Examine cultural integration through leisure and holidays |

| Authors | Kossakowski et al. (2016) | Lenneis and Pfister (2016) | Lorentzen and Viken (2020) | Lorentzen and Viken (2021) | Nowicka (2016) |

| Outcomes | Barriers include the Swedish climate, prior PA experience, and other time-consuming commitments. | The sports activities function as social and emotional safe spaces for Bosnians but are perceived as segregating by local federations. | Recruitment of the Yugoslavian migrants was hindered by linguistic barriers and failure to identify contact information. | Females are at greater risk for physical inactivity, while no differences are found between Swedes and male Yugoslavian and male Polish migrants. | Females are more physically inactive than men and Swedes but less inactive than other migrant groups. However, only Polish men display significantly higher BMI compared to Swedes. |

| Country | Sweden | Norway | Sweden | Sweden | Sweden |

| Sample | Seven former Yugoslavian female migrants | Representatives from seven Muslim organizations, out of which one was Bosnian | 40 migrants from the former Yugoslavia and Finland | 5600 migrants, out of which 148 were from Yugoslavia and 130 were from Poland | 1966 migrants, out of which 568 were from Poland |

| Theory | No clearly outlined theoretical framework | Putnam’s social capital theory | A person-centered (health) approach | No clearly outlined theoretical framework | No clearly outlined theoretical framework |

| Method | Semi-structured interviews | Semi-structured interviews and participant observation | Randomized controlled trial (RCT) | Cross-sectional observational data | Cross-sectional observational data |

| Purpose | To explore enablers and constraints for PA in Yugoslavian migrant females | To explore Muslim organization’s role in using sports to integrate migrants into Norwegian society | To examine the feasibility of a health-promotion program’s protocol | To examine the relationship between PA and migration status | To examine relationships between education, age, body mass index (BMI), and sedentary lifestyle |

| Authors | Sandström et al. (2015) | Walseth (2016) | Lood et al. (2015) | Lindström and Sundquist (2001) | Wändell et al. (2004) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mickelsson, T.B. Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120452

Mickelsson TB. Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(12):452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120452

Chicago/Turabian StyleMickelsson, Tony Blomqvist. 2021. "Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review" Social Sciences 10, no. 12: 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120452

APA StyleMickelsson, T. B. (2021). Towards Understanding Post-Socialist Migrants’ Access to Physical Activity in the Nordic Region: A Critical Realist Integrative Review. Social Sciences, 10(12), 452. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10120452