Monetary Fiscal Contributions to Households and Pension Fund Withdrawals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Approximation of Their Impact on Construction Labor Supply in Chile

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methodology

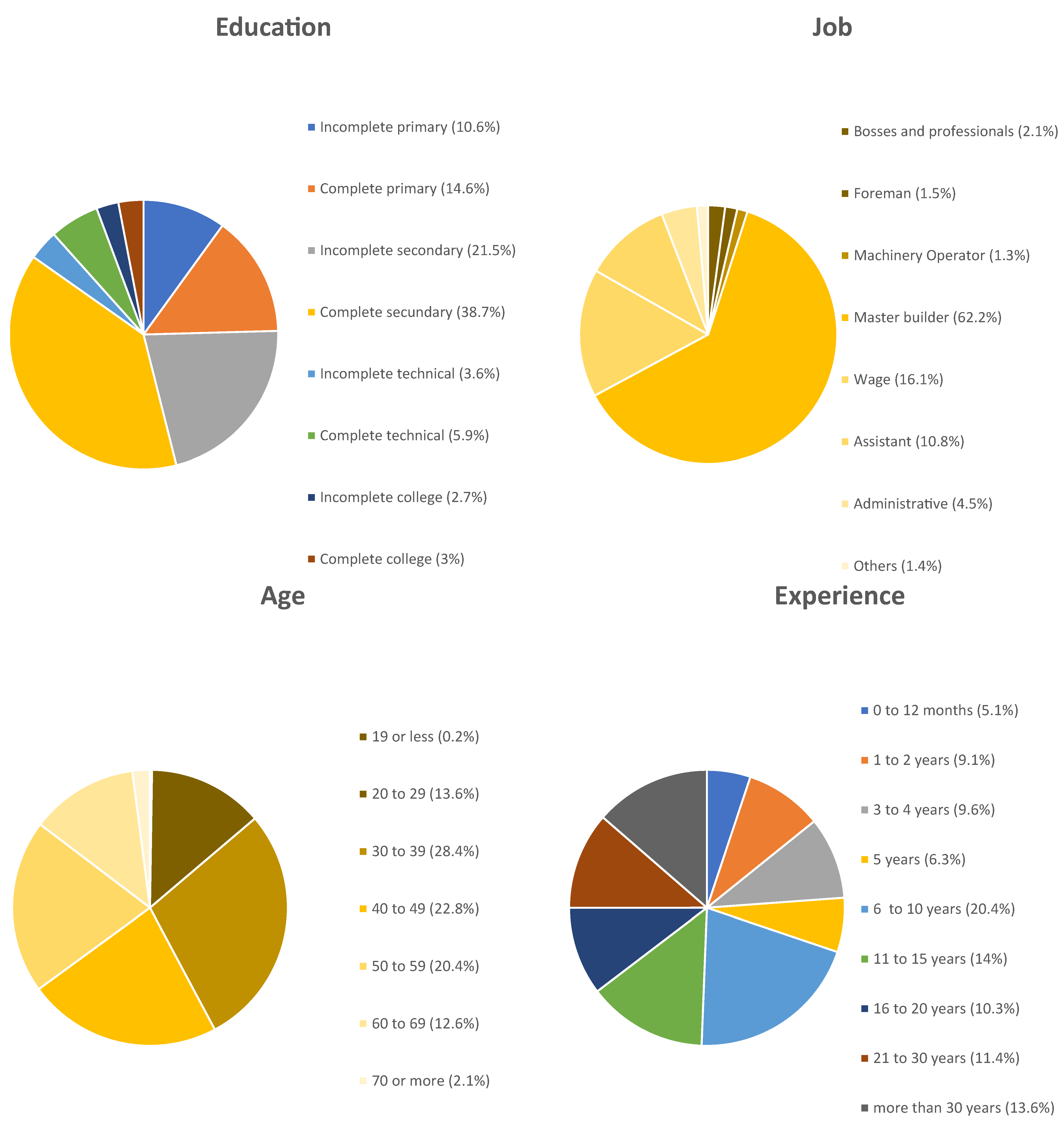

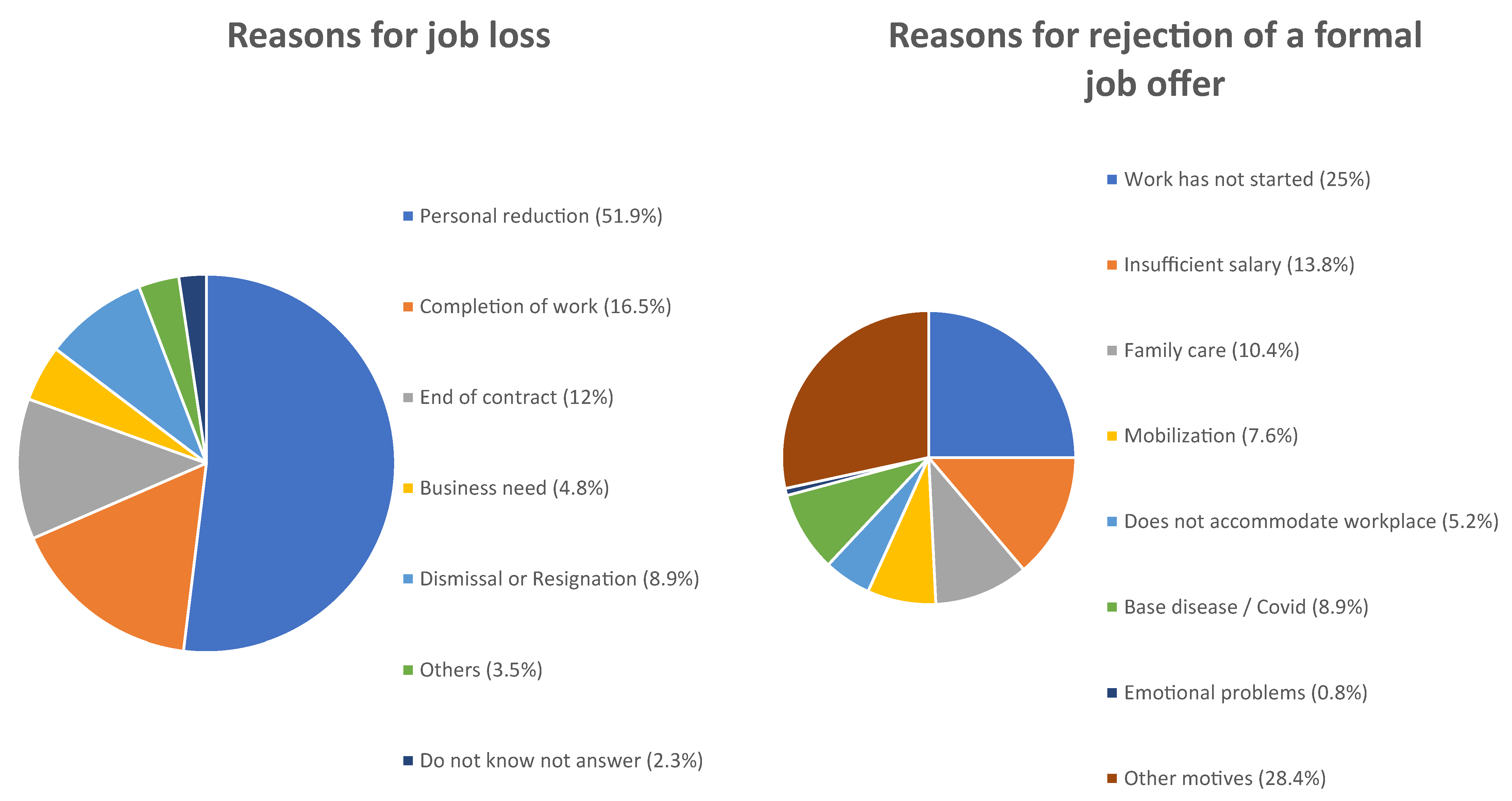

2.1. Data Collection

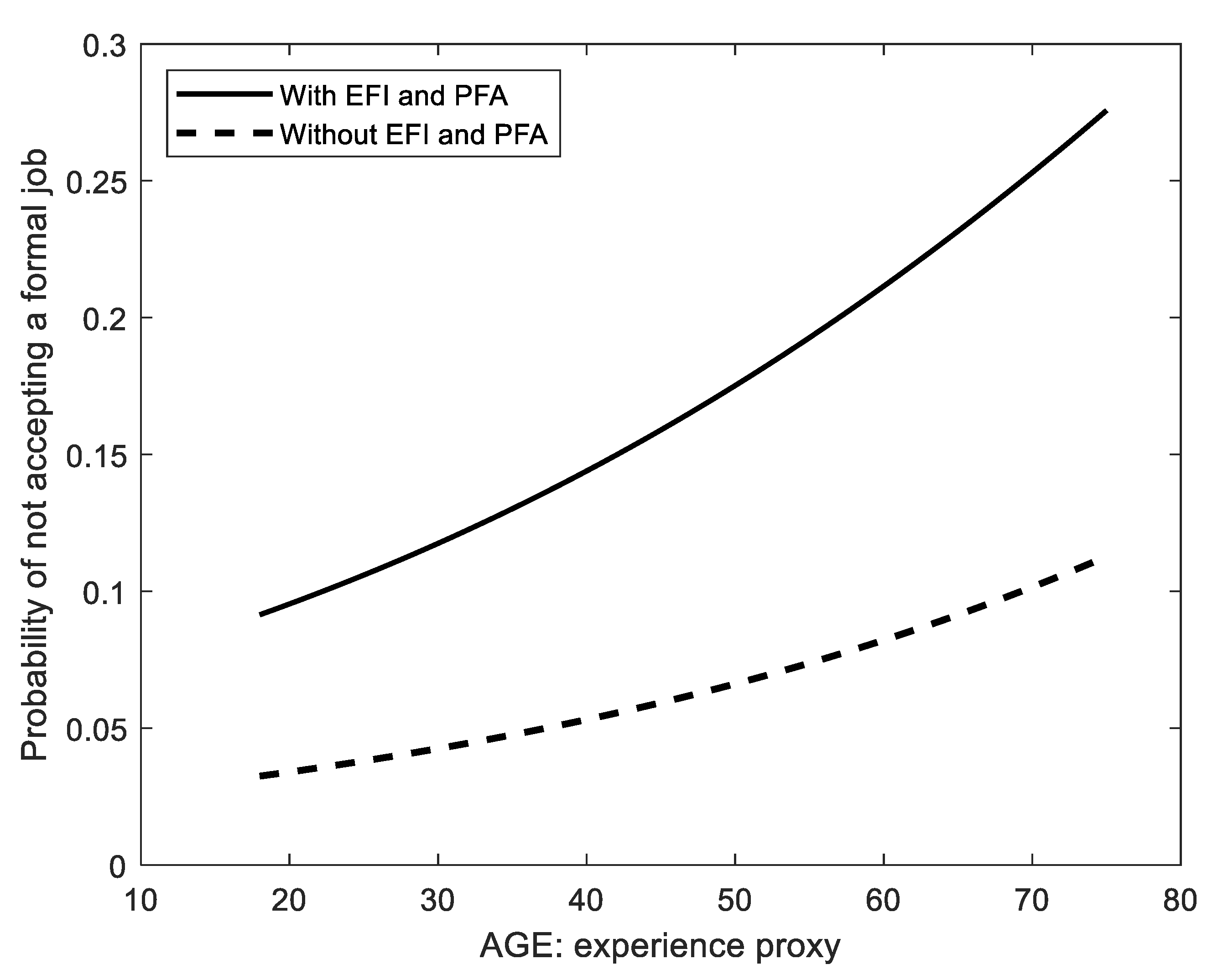

2.2. Statistical Modelling

3. Results

- Of the total, 68% would work in the informal market. Of these, 64% claimed to have received less than US$635 per month. This amount is not substantially different from a construction worker’s average market salary of US$676.91 per month.

- Also, 72% of respondents had debt of less than US$317.50. Assuming most of these credits were acquired in the formal financial market, the amount could count as debt deferral benefit, involving an extension of loan maturity implemented in 2020 by the Financial Market Commission (FMC), which regulates the sector, and the Central Bank.

- Considering informal income and the debt deferral benefit, a percentage of unemployed workers could be receiving an amount higher than the average market salary (around US$676.91 per month). Therefore, from a worker’s short-term perspective, working in the informal market carries greater benefit than cost.

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Asahi, Kenzo, Eduardo A. Undurraga, Rodrigo Valdés, and Rodrigo Wagner. 2021. The effect of COVID-19 on the economy: Evidence from an early adopter of localized lockdowns. Journal of Global Health 11: 05002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atutxa, Ekhi, Iñigo Calvo-Sotomayor, and Teresa Laespada. 2021. The Employment Ecosystem of Bizkaia as an Emerging Common in the Face of the Impact of COVID-19. Social Sciences 10: 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banco Central de Chile. 2021a. Informe de Percepción de Negocios (IPN). Santiago: Banco Central de Chile, February, Available online: https://www.bcentral.cl/contenido/-/detalle/informe-de-percepciones-de-negocios-febrero-2021 (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Banco Central de Chile. 2021b. Informe de Percepción de Negocios (IPN). Santiago: Banco Central de Chile, August, Available online: https://www.bcentral.cl/contenido/-/detalle/informe-de-percepciones-de-negocios-agosto-2021 (accessed on 30 September 2021).

- Behrman, Jere, Maria Cecilia Calderon, Olivia S. Mitchell, Javiera Vasquez, and David Bravo. 2011. First-Round Impacts of the 2008 Chilean Pension System Reform. Michigan Retirement Research Center Research Paper No. WP, 245. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, Available online: https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1032&context=parc_working_papers (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Bennett, Magdalena. 2021. All things equal? Heterogeneity in policy effectiveness against COVID-19 spread in Chile. World Development 137: 105208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berstein, Solange, Olga Fuentes, and Félix Villatoro. 2013. Default investment strategies in a defined contribution pension system: A pension risk model application for the Chilean case. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 12: 379–414. [Google Scholar]

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción. 2019. Informe de Caracterización de los Trabajadores de la Construcción. Available online: https://extension.cchc.cl/datafiles/45342-2.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción. 2020. Fundación Social. Available online: https://cchc.cl/social/fundacion-social (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Cámara Chilena de la Construcción. 2021. Informe de Macroeconomía y Construcción (MACh 56). Santiago: Cámara Chilena de la Construcción, Available online: https://cchc.cl/uploads/archivos/archivos/mach-56.pdf (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Contreras-Reyes, Javier E., and Byron J. Idrovo-Aguirre. 2020. Backcasting and forecasting time series using detrended cross-correlation analysis. Physica A 560: 125109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fosco, Constanza, and Felipe Zurita. 2021. Assessing the short-run effects of lockdown policies on economic activity, with an application to the Santiago Metropolitan Region, Chile. PLoS ONE 16: e0252938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gil, Diego, Patricio Dominguez, Eduardo A. Undurraga, and Eduardo Valenzuela. 2021. The Socioeconomic Impact of COVID-19 in Urban Informal Settlements. medRxiv. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobierno de Chile. 2021. Ingreso Familiar de Emergencia (IFE) Universal. Santiago: Red de Protección Social del Ministerio de Desarrollo Social y Familia e IPS del Ministerio del Trabajo y Previsión Social, Gobierno de Chile, Available online: https://www.ingresodeemergencia.cl/ (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Gozzi, Nicolò, Michele Tizzoni, Matteo Chinazzi, Leo Ferres, Alessandro Vespignani, and Nicola Perra. 2021. Estimating the effect of social inequalities on the mitigation of COVID-19 across communities in Santiago de Chile. Nature Communications 12: 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greene, William H. 2002. Econometric Analysis, 5th ed. Hoboken: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. 2021. Gobierno de Chile, Santiago, Chile. Available online: https://www.ine.cl (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Idrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., and Victor D. Serey. 2018. Total factor productivity for the Chilean construction sector (1986–2015). Economic Analysis Review 33: 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Idrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., Francisco J. Lozano, and Javier E. Contreras-Reyes. 2021. Prosperity or Real Estate Bubble? Exuberance probability index of the Real Price of Housing in Chile. International Journal of Financial Studies 9: 51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., and Javier E. Contreras-Reyes. 2019. Backcasting cement production and characterizing cement’s economic cycles for Chile 1991–2015. Empirical Economics 57: 1829–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., and Javier E. Contreras-Reyes. 2021a. Bayesian monthly index for building activity based on mixed frequencies: The case of Chile. Journal of Economic Studies. in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., and Javier E. Contreras-Reyes. 2021b. The response of housing construction to a copper price shock in Chile (2009–2020). Economies 9: 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matlab. 2019. MATLAB. version R2019b. Natick: The MathWorks Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mena, Gonzalo E., Pamela P. Martinez, Ayesha S. Mahmud, Pablo A. Marquet, Caroline O. Buckee, and Mauricio Santillana. 2021. Socioeconomic status determines COVID-19 incidence and related mortality in Santiago, Chile. Science 372: 934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mittelstaedt, H. Fred, and John C. Olsen. 2003. An empirical analysis of the investment performance of the Chilean pension system. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 2: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- Modrego, Félix, Andrea Canales, and Héctor Bahamonde. 2020. Employment effects of COVID-19 across Chilean regions: An application of the translog cost function. Regional Science Policy & Practice 12: 1151–67. [Google Scholar]

- Smart, Sebastian, and Vicente Burgos. 2018. Chilean housing policy: A pendant human rights perspective. Journal of Property, Planning and Environmental Law 10: 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, Pravin K. 2009. Microeconometrics. In Encyclopedia of Complexity and Systems Science. Edited by Robert Meyers. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

| Variable | Definition |

|---|---|

| PFA withdrawal | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker withdrew less than US$317.50 and value 0 in any other case. |

| Received EFI (less than US$317.50) | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker received less than US$317.50 from the EFI and value 0 otherwise. |

| PFA withdrawal and EFI received | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker withdrew PFA funds and received the EFI benefit. Value 0 otherwise. |

| Worked informally during April–June | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker performed an informal job during the April–May–June quarter and value 0 otherwise. |

| Received between US$317.50 and US$635 for informal work during April–June | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker received between US$317.50 and US$635 for performing informal work during the April–May–June quarter and value 0 otherwise. |

| Debt payments between US$317.50 and US$635 monthly | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker declared a debt expense between US$317.50 and US$635 per month and value 0 otherwise. |

| Expects income increase within 12 months | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker believed income would rise within the next 12 months and value 0 otherwise. |

| Gender | The variable takes value 1 if the unemployed worker was male and value 0 if female. |

| Age (proxy of work experience) | Continuous variable that measures the unemployed worker’s age in years. |

| Has secondary or technical education | The variable takes value of 1 if the unemployed worker attended secondary or technical education. |

| Factor | No Applies | Less than US$317.50 | From US$317.50 to US$635 | From US$635 to US$952.50 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informal work | 32 | 37.9 | 26.2 | 3.9 |

| Basic services and food | 0 | 38.7 | 56.5 | 4.4 |

| Debts | 0 | 72.1 | 25.7 | 2.2 |

| Coefficients | Marginal Effect | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Value | St. Error | p-Value | Value | St. Error | p-Value |

| Constant | −1.893 () | 0.434 | <0.01 | −0.232 () | 0.052 | <0.01 |

| PFA withdrawal | −0.719 () | 0.272 | <0.01 | −0.088 () | 0.033 | <0.01 |

| Received EFI (less than US$317.50) | −0.309 () | 0.141 | 0.028 | −0.038 () | 0.017 | 0.028 |

| PFA withdrawal and EFI received | 1.097 () | 0.331 | <0.01 | 0.135 () | 0.040 | <0.01 |

| Worked informally during April–June | −1.320 () | 0.168 | <0.01 | −0.162 () | 0.020 | <0.01 |

| US$317.50–US$635 received for informal work during April–June | −0.845 () | 0.184 | <0.01 | −0.104 () | 0.023 | <0.01 |

| Between US$317.50 and US$635 monthly debt expense | −0.393 () | 0.168 | 0.020 | −0.048 () | 0.021 | 0.019 |

| Expects rising incomes within 12 months | −0.472 () | 0.146 | <0.01 | −0.058 () | 0.018 | <0.01 |

| Gender | −0.531 () | 0.170 | <0.01 | −0.065 () | 0.021 | <0.01 |

| Age (proxy work experience) | 0.023 () | 0.006 | <0.01 | 0.003 () | 0.001 | <0.01 |

| Declared a level of secondary or technical education | −0.303 () | 0.144 | 0.036 | −0.037 () | 0.018 | 0.036 |

| N | 1704 | |||||

| Wald test | 536.825 () | |||||

| p-Value | <0.01 | |||||

| Predictive capacity assessment: | ||||||

| Accuracy when observed variable = 1 | 61% | |||||

| Accuracy when observed variable = 0 | 84% | |||||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Idrovo-Aguirre, B.J.; Contreras-Reyes, J.E. Monetary Fiscal Contributions to Households and Pension Fund Withdrawals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Approximation of Their Impact on Construction Labor Supply in Chile. Soc. Sci. 2021, 10, 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110417

Idrovo-Aguirre BJ, Contreras-Reyes JE. Monetary Fiscal Contributions to Households and Pension Fund Withdrawals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Approximation of Their Impact on Construction Labor Supply in Chile. Social Sciences. 2021; 10(11):417. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110417

Chicago/Turabian StyleIdrovo-Aguirre, Byron J., and Javier E. Contreras-Reyes. 2021. "Monetary Fiscal Contributions to Households and Pension Fund Withdrawals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Approximation of Their Impact on Construction Labor Supply in Chile" Social Sciences 10, no. 11: 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110417

APA StyleIdrovo-Aguirre, B. J., & Contreras-Reyes, J. E. (2021). Monetary Fiscal Contributions to Households and Pension Fund Withdrawals during the COVID-19 Pandemic: An Approximation of Their Impact on Construction Labor Supply in Chile. Social Sciences, 10(11), 417. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci10110417