Abstract

There has been a lot of interest in digital mental health interventions but adherence to online programmes has been less than optimal. Chatbots that mimic brief conversations may be a more engaging and acceptable mode of delivery. We developed a chatbot, called 21-Day Stress Detox, to deliver stress management techniques for young adults. The purpose of the study was to explore the feasibility, acceptability, and potential efficacy of this low-intensity digital mental health intervention in a non-clinical population of young adults. The content was derived from cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) and included evidence-informed elements such as mindfulness and gratitude journaling. It was delivered over 21 daily sessions using the Facebook Messenger platform. Each session was intended to last about 5–7 min and included text, animated GIFs, relaxation tracks and reflective exercises. We conducted an open single-arm trial collecting app usage through passive data collection as well as self-rated satisfaction and qualitative (open-ended) feedback. Efficacy was assessed via outcome measures of well-being (World Health Organisation (Five) Well-being Index; WHO-5; and Personal Well-being Measure; ONS4); stress (Perceived Stress Scale–10 item version; PSS-10); and anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale; GAD-7). One hundred and ten of the 124 participants who completed baseline commenced the chatbot and 64 returned the post-intervention assessment. Eighty-one percent were female and 51% were first year students. Forty-five percent were NZ European and 41% were Asian. Mean engagement was 11 days out 21 days (SD = 7.8). Most (81%) found the chatbot easy to use. Sixty-three percent rated their satisfaction as 7 out of 10 or higher. Qualitative feedback revealed that convenience and relatable content were the most valued features. There was a statistically significant improvement on the WHO-5 of 7.38 (SD = 15.07; p < 0.001) and a mean reduction on the PSS-10 of 1.77 (SD = 4.69; p = 0.004) equating to effect sizes of 0.49 and 0.38, respectively. Those who were clinically anxious at baseline (n = 25) experienced a greater reduction of GAD-7 symptoms than those (n = 39) who started the study without clinical anxiety (−1.56, SD = 3.31 vs. 0.67, SD = 3.30; p = 0.011). Using a chatbot to deliver universal psychological support appears to be feasible, acceptable, have good levels of engagement, and lead to significant improvements in well-being and stress. Future iterations of the chatbot should involve a more personalised content.

1. Introduction

The transition from adolescence to adulthood is characterised by unique social, psychological and health issues (Shanahan 2000). Major life changes, including completing education or training, starting a career or entering an intimate relationship, can trigger or amplify underlying mental health problems, sometimes leading to psychological distress or maladaptive functioning (Patel et al. 2007). It is estimated that up to 75% of lifetime mental health disorders emerge by the age of 24 (Kessler et al. 2005). In particular, anxiety has been singled out as a significant and frequent concern with 12-month prevalence rates of 22.2% in the USA (Kessler et al. 2012), 20% in Australia (Forbes et al. 2017), and 19.4% in New Zealand (Oakley Browne et al. 2006). There is evidence that prevalence of anxiety had been increasing in tertiary students pre-2020 (Xiao et al. 2017), and there are emerging trends of increase in anxiety since the start of the Covid pandemic in 2020 (Huckins et al. 2020; MHA National 2021). Young adults are less likely than their older counterparts to access ‘traditional’ mental health services (Gulliver et al. 2010). If left untreated, mental health difficulties can become chronic, entrenched, and debilitating problems (Gustavson et al. 2018; Kessler et al. 2007; Silfvernagel et al. 2017).

Tertiary students have been the target of several technology-based interventions. A recent meta-analysis found that about half (47%) of the 89 included programmes were effective and 34% were partially effective at reducing symptoms of the targeted disorder (Lattie et al. 2019). However, many of the studies showed high rates of attrition and low sustained usage. One way to boost engagement may be to use existing channels (such as instant messenger) to deliver digital interventions. This could reach people on the platform that is already familiar to them; the content could be broken down into shorter and easier- to-navigate chunks, while, in turn, the interventions might fit better into daily routine and modern habits.

Chatbots are computer programs that simulate conversation usually via a synchronous text-based dialogue. They allow real time engagement at a time and location of choice through what is considered a more natural interaction (Linardon et al. 2019). In a mental health context, chatbots are said to provide an instant service mimicking a counsellor or a peer who is instantly accessible to answer questions, provide advice, and engage in a friendly and supportive manner. Unsurprisingly, a number of chatbots to support mental health have been developed in the last few years (Vaidyam et al. 2019). One of the more popular (in terms of downloads) is Woebot (Fitzpatrick et al. 2017), which was shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms compared to an active information-only control group with 34 young adults. Similarly, Wysa, is an Artificial Intelligence-enabled, empathetic, text-based conversational mobile mental well-being app (Inkster et al. 2018). In a ‘real-world open trial’, users who engaged with Wysa frequently had significantly higher improvement on depression scores than ‘low-engagers’.

Rationale for the Current Study

At the time of this study (2019), no therapeutic chatbots had been developed or evaluated in the New Zealand context. Our objective was to develop tailored content for young adults in this country to reflect local themes and style of communication.

The 21-Day Stress Detox is a self-help digital (Chatbot) intervention that sits on the HABITs (Health Advances Through Behaviour Intervention Technologies) platform – a digital ecosystem developed by the University of Auckland to support co-design, development, and evaluation of digital tools for mental health support (Warren et al. 2020). The chatbot uses Facebook Messenger to deliver a daily content (full description of the content and the delivery methods are included in the Methods section).

2. Materials and Methods

All participants gave their informed consent before taking part in the study. Consent was collected electronically using a secure online study portal. The study was approved on June 18th 2019 by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (protocol number 023234). This trial was prospectively registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (https://www.anzctr.org.au/ Trial ID: ACTRN12619001333101).

There was no compensation offered but participants who entered the study were given a chance to win one of five $NZ50 (about US$35) shopping vouchers.

2.1. Study Design

This was an open trial single-arm pilot study to determine the feasibility and acceptability of the 21 Day Stress Detox chatbot. The primary aim of the trial was to assess adherence, engagement, and satisfaction. The secondary objective was to explore changes in well-being, stress, and anxiety from pre- to post-intervention.

2.1.1. Recruitment

Potential participants were recruited from a non-clinical sample of University of Auckland students. The study was advertised directly to students using electronic announcements on a student portal, University research recruitment page, and brief (2 min) in-person (by RW) invitation to the study to a few undergraduate classes. The invitation to the study called for students who self-identified as “stressed” to try a “21-Day Stress Detox”.

Inclusion criteria encompassed being 18–24 years of age, able to read English (implied), and to have access to the internet via a smartphone or device/computer with a Facebook Messenger account. As recruitment was carried out fully online, it was up to each individual participant to deem if they were eligible to participate.

2.1.2. Procedure

The invitation (flyer or email) to study contained a URL link and QR code to the study website with further information, including a Participant Information Sheet and an outline of study procedures. Once a potential participant read this information, they were asked to provide electronic consent and complete baseline assessments using the online portal. It took approximately 10–15 min. Finally, participants were provided with a link to the intervention, which commenced within Facebook Messenger under their account.

2.1.3. Intervention

The 21-Day Stress Detox is a low-intensity psychological intervention designed to provide content in daily instalments to teach and reinforce coping strategies for dealing with stress and anxiety. Week one focused on physiological sensations associated with stress and anxiety (i.e., feelings–represented in the chatbot as  ); week two focused on cognitive appraisal of stress and anxiety (i.e., thinking–represented in the chatbot as

); week two focused on cognitive appraisal of stress and anxiety (i.e., thinking–represented in the chatbot as  ); and week three focused on behavioural response (i.e., action–represented in the chatbot as

); and week three focused on behavioural response (i.e., action–represented in the chatbot as  ). Day 22 was ‘content-free’ and consisted of a message prompting the participant to complete the post-intervention assessment. Participants who did not reach that point were sent an email on day 22 and two reminders (a week apart) to complete the post-intervention measures via the online study portal. The chatbot content is based on the cognitive behavioural (CBT) model alongside techniques derived from positive psychology i.e., expressing gratitude (Fava et al. 1998) and scheduling time for pleasant activities (Fuchs and Rehm 1977; Wirtz and von Känel 2017). This is conveyed through motivational quotes, jokes, gratitude journaling, and activities to help form positive habits. A summary of content of the intervention is presented in Table 1.

). Day 22 was ‘content-free’ and consisted of a message prompting the participant to complete the post-intervention assessment. Participants who did not reach that point were sent an email on day 22 and two reminders (a week apart) to complete the post-intervention measures via the online study portal. The chatbot content is based on the cognitive behavioural (CBT) model alongside techniques derived from positive psychology i.e., expressing gratitude (Fava et al. 1998) and scheduling time for pleasant activities (Fuchs and Rehm 1977; Wirtz and von Känel 2017). This is conveyed through motivational quotes, jokes, gratitude journaling, and activities to help form positive habits. A summary of content of the intervention is presented in Table 1.

); week two focused on cognitive appraisal of stress and anxiety (i.e., thinking–represented in the chatbot as

); week two focused on cognitive appraisal of stress and anxiety (i.e., thinking–represented in the chatbot as  ); and week three focused on behavioural response (i.e., action–represented in the chatbot as

); and week three focused on behavioural response (i.e., action–represented in the chatbot as  ). Day 22 was ‘content-free’ and consisted of a message prompting the participant to complete the post-intervention assessment. Participants who did not reach that point were sent an email on day 22 and two reminders (a week apart) to complete the post-intervention measures via the online study portal. The chatbot content is based on the cognitive behavioural (CBT) model alongside techniques derived from positive psychology i.e., expressing gratitude (Fava et al. 1998) and scheduling time for pleasant activities (Fuchs and Rehm 1977; Wirtz and von Känel 2017). This is conveyed through motivational quotes, jokes, gratitude journaling, and activities to help form positive habits. A summary of content of the intervention is presented in Table 1.

). Day 22 was ‘content-free’ and consisted of a message prompting the participant to complete the post-intervention assessment. Participants who did not reach that point were sent an email on day 22 and two reminders (a week apart) to complete the post-intervention measures via the online study portal. The chatbot content is based on the cognitive behavioural (CBT) model alongside techniques derived from positive psychology i.e., expressing gratitude (Fava et al. 1998) and scheduling time for pleasant activities (Fuchs and Rehm 1977; Wirtz and von Känel 2017). This is conveyed through motivational quotes, jokes, gratitude journaling, and activities to help form positive habits. A summary of content of the intervention is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of content of the 21-Day Stress Detox Chatbot.

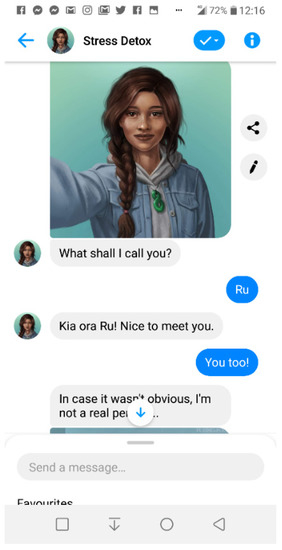

The persona of the chatbot is a young person who messages the user via Facebook Messenger once a day (at a time chosen by the user) and guides them through a brief (about 3–5 min) daily activity. The interaction is akin to a brief exchange with a friend who checks in and has a helpful tip or an anecdote/story to share. The user can choose to engage or to ignore. If ignored, the chatbot checks in again 24 h later. The messages typically start with “Hi, how are you going today?” which is hypothesised to be an effective way of generating a conversational interaction (Schegloff (1968)).

In the event that a participant was distressed and needed additional support, there were ‘risk’ words programmed into the system, which triggered a “more help” module. This included presentation of appropriate helplines and how/where to seek more comprehensive support. Information about extra help, including helplines, was also included at the entry and exit from the study via the portal.

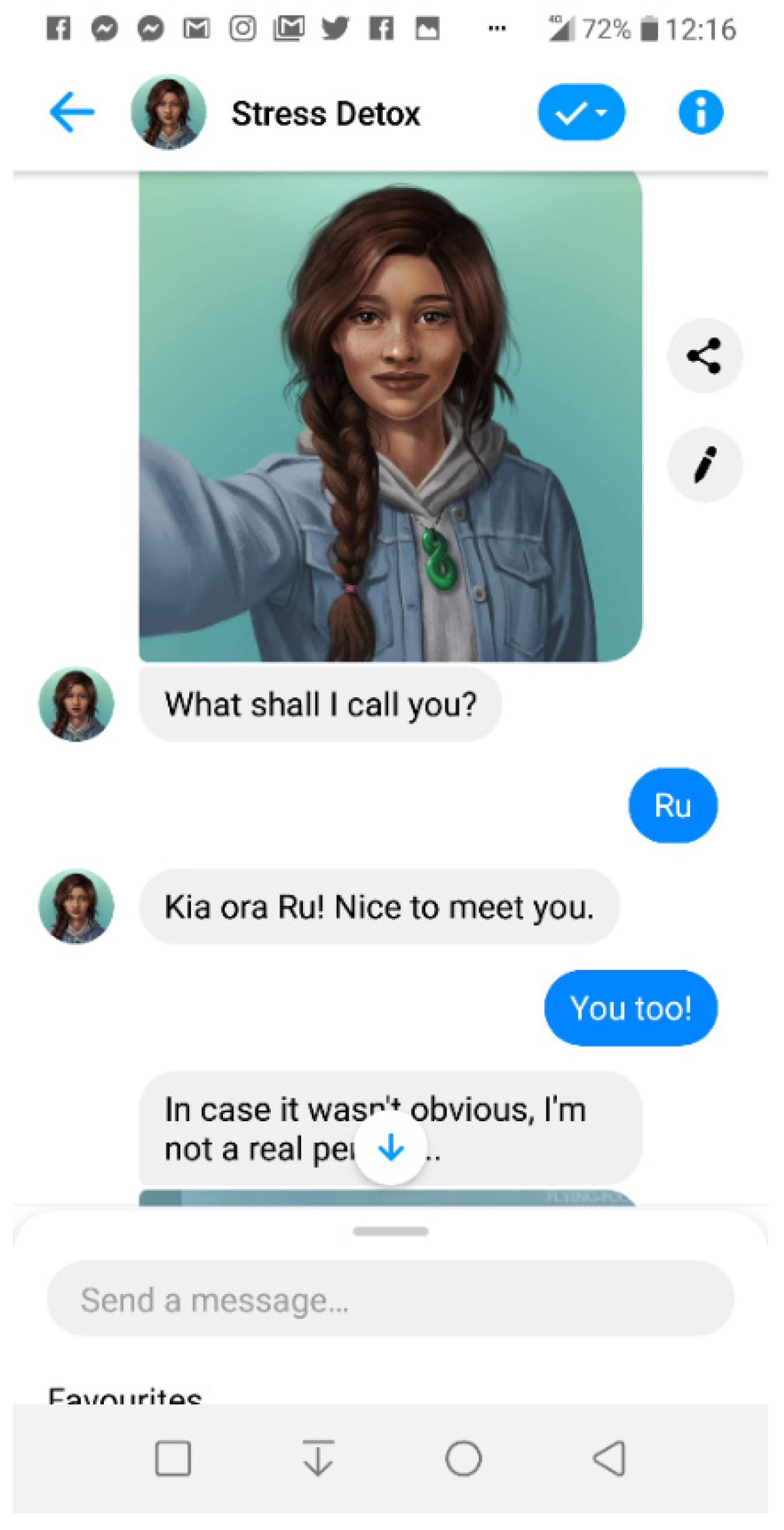

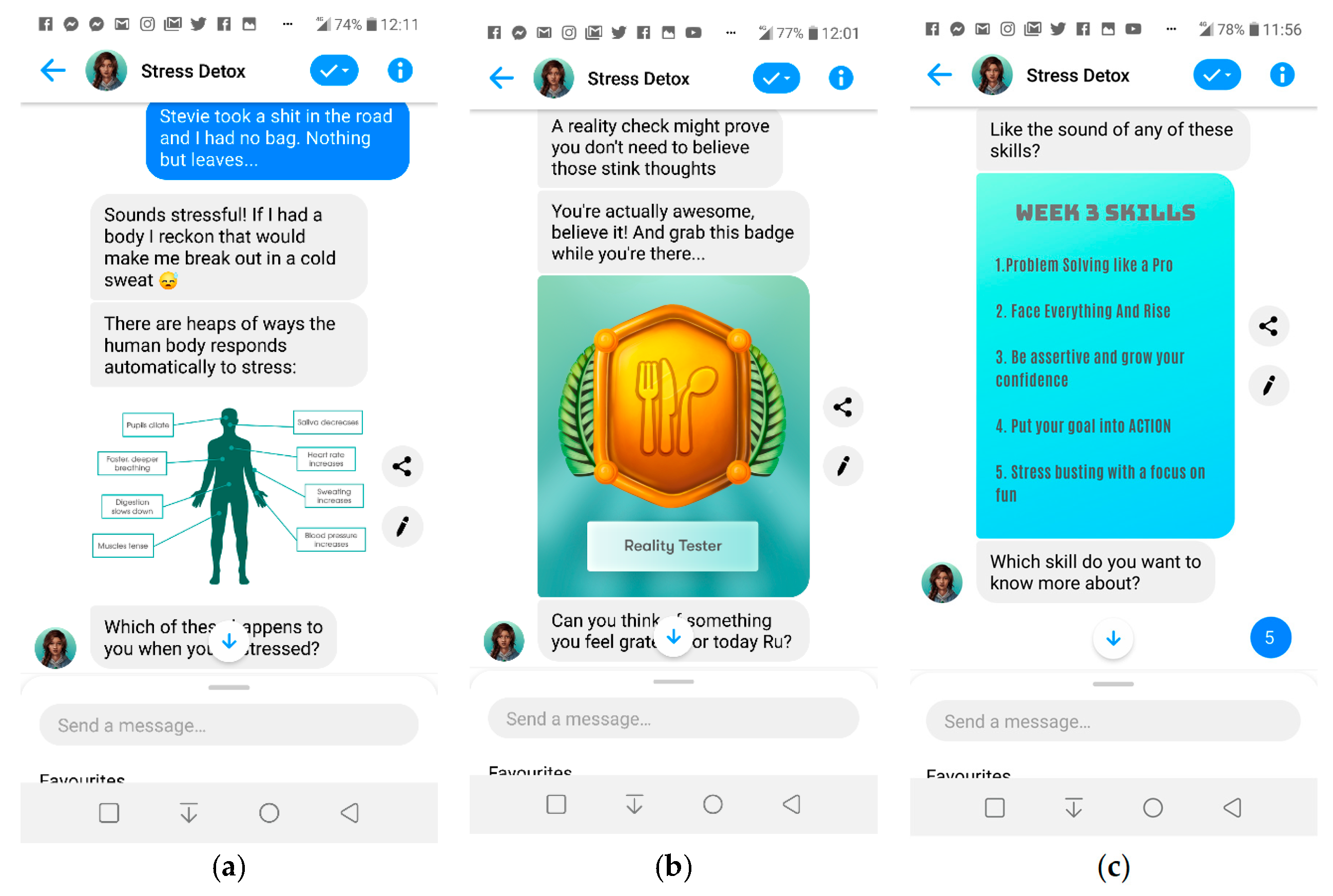

An example of first day interaction (‘meet and greet’) is shown in Figure 1, and further screenshots (Figure 2) illustrate the chatbot’s content and communication style.

Figure 1.

Screenshot of day one onboarding with “Aroha”, the Stress Detox chatbot persona.

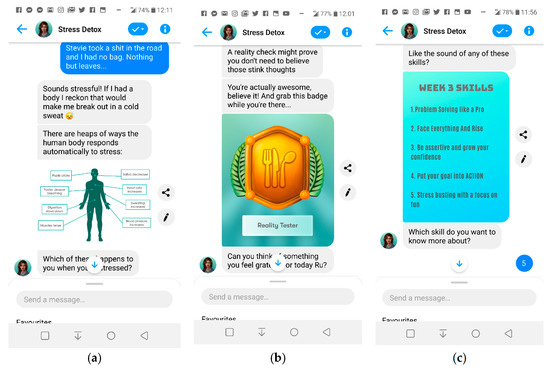

Figure 2.

Screenshots of: (a) day four Stress Psychoeducation module; (b) day ten Reality Check module; (c) day thirteen Perspective module.

The 21-Day Stress Detox is built on “rule-based” programming (Holt-Quick et al. 2021). The majority of the content is in the form of a dialogue based on predetermined ‘quick options’ (e.g., yes/no or ‘tell me more’/’let’s go’) that branch out the conversation along the user-chosen path. The written content is further enhanced using audio clips (relaxation, mindfulness, and guided meditation tracks), GIFs (for humour or metaphor), while reflective exercises, vignettes, brief quizzes, homework (framed as ‘challenges’) are used to present and augment skill acquisition. Gamification strategies are used to sustain motivation using collectible reward badges for each newly acquired skill and for completing each week. Users can also ‘favourite’ their activities and access them through a quick menu. While each day presents new content, there is scope to repeat some activities if needed. The language throughout the intervention is non-clinical and the emphasis is on everyday skills and healthy ways of coping. The chatbot persona has an upbeat and friendly tone, using validating statements to empathise and encourage motivation. Whenever possible, text is reduced and kept simple and non-technical. Jargon is avoided and, instead, more colloquial, youth friendly language is used.

- a.

- Data Collection

Data was collected and stored electronically (via an online portal) using self-reported (outcomes and satisfaction) and passive (usage) methods. Both quantitative and qualitative data were collected as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of measures used in the study.

- b.

- Outcome measurement

Adherence was captured quantitatively as the number of days a participant interacted with the chatbot. We also measured how many different modules participants accessed. However, the design of the chatbot allowed for flexible use: participants were able to repeat some of the modules as many times as they wished (e.g., listen to relaxation tracks more than once or ‘favorite’ a module and repeat it later). On the other hand, there were also modules that participants could skip (e.g., not complete the gratitude journal). Therefore, there is no objective ‘maximum’ number of modules that can be completed.

Satisfaction with the chatbot was assessed during the intervention (on day 7, 14, and 21) as a brief self-report measure with three options: “lame”, “okay”, or “great”. At post-intervention, participants were asked to complete a measure called the “Chatbot Rating Scale”. This scale was developed for the study with seven questions pertaining to the domains of: ease of use, aesthetic, relevance of content, cultural fit/responsiveness, technical functioning, satisfaction with the experience, and desire to keep using in future. Each item could be rated on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 4 (definitely.) At the end of the Rating Scale, participants were asked to rate the chatbot globally on a scale of 1–10 (1 being ‘Really bad’ and 10 being ‘Amazing’). Free-text feedback was collected about the chatbot by asking the participants to state what they ‘liked most’ and ‘liked least’ about the chatbot, and what suggestions for improvement they had. These were optional questions and could be skipped.

Efficacy was measured using several psychometrically validated outcome measures: the Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) (Cohen et al. 1994) is a self-report tool to assess the frequency of thoughts and feelings relating to situations that have occurred recently. Items measure how overwhelming, uncontrollable, and overloaded life feels. The PSS-10 is a short version of the scale, which has been shown to be of equal reliability and validity to the longer version (Cohen et al. 1994), but a lesser burden on participants. PSS-10 is deemed to be a reliable assessment of perceived stress (Cronbach’s alpha 0.89) (Roberti et al. (2006)) and has a good convergent validity with the State Trait Anxiety Inventory (Taylor 2015). It is one of the most widely used psychological instruments for measuring stress (Cohen et al. 1994).

The Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) is a valid, brief self-report tool to assess the frequency and severity of anxious thoughts and behaviours over the past two weeks (Spitzer et al. 2006). This has good internal consistency (ρ = 0.85) and convergent validity with other anxiety measures. A score of 10 or greater is used to indicate moderate anxiety (Spitzer et al. 2006).

The World Health Organisation (Five) Well-being Index (WHO-5) (Staehr Johansen 1998) is a self-report five-item measure of subjective happiness made up exclusively of positively-phrased items. It has adequate construct validity for positive mood, vitality, and general interest (Feicht et al. 2013) and is reliable (Cronbach’s α = 0.88; Bech et al. (2003)).

The Personal Well-being Measure (ONS4) (Tinkler and Hicks 2011) is a four-item self-report measure consisting of four independent items (i.e., there is no composite score): life satisfaction (‘Overall, how satisfied are you with your life nowadays?’); worthwhile (‘Overall, to what extent do you feel that the things you do in your life are worthwhile?’); happiness (‘Overall, how happy did you feel yesterday?’); and anxiety (‘On a scale of where 0 is not at all anxious and 10 is completely anxious, overall how anxious did you feel yesterday?’). Each item is answered on a scale from 0 to 10 where 0 is ‘’not at all’ and 10 is ‘completely”. As a personal well-being measure, it has been applied to large non-clinical populations via representative surveys. The ONS4 was recently recommended as a preferred measure of personal well-being when a limited number of items can be administered (VanderWeele et al. 2020).

- c.

- Data analysis

The clinical outcomes were summarised for all participants at baseline using descriptive summaries. Levels and changes in the outcome measures were summarised as means and standard deviations. Pre-post mean change scores were calculated for each clinical outcome. Paired sample t-tests were used to assess statistical significance. Changes in the outcome measures were tested using paired t-tests and summarised as means with 95% confidence intervals. Associations between gender, ethnicity, and baseline GAD-7 score, and changes in the outcome measures were tested using a 1-way ANOVA.

Participant responses to open-ended questions were analysed qualitatively using a pragmatic general inductive approach to qualitative analysis. This was guided by the procedure outlined by Thomas (2006), with qualitative content analysis building understanding from observation rather than hypothesis testing. This method focuses on understanding the perspectives of participants responding to specific evaluation questions (Patton 2002). Content was analysed in relation to the question: “Is the chatbot acceptable to the participants?”, with each response being read closely multiple times to derive initial categories that related to this research question. Related content was pulled out and grouped into sub-themes, which fed into common themes. RW read and re-read each response and created the initial coding framework. This was discussed and cross-checked on a sample of responses by KS.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

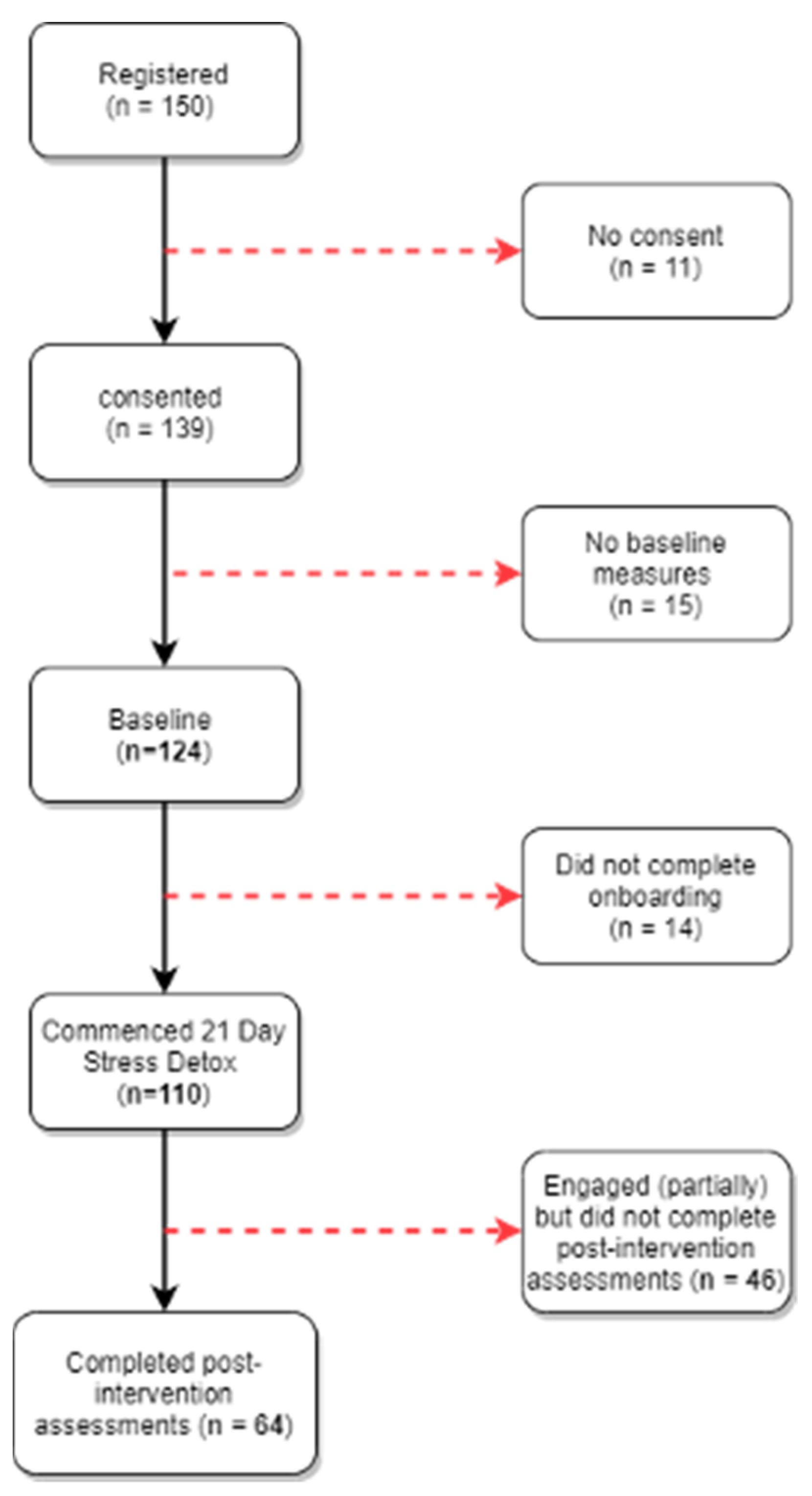

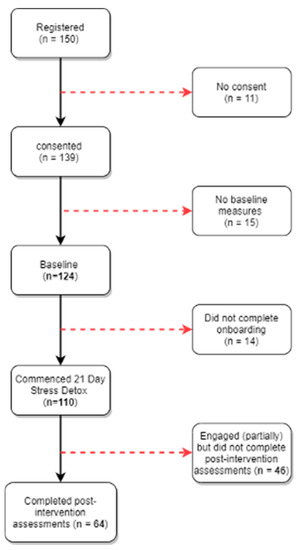

Recruitment took place at the University of Auckland (New Zealand) between October 7, and November 15, 2019 coinciding with the end of the second semester and the exam period. Participant flow is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flowchart of the participants through the trial.

Participants were predominantly female, most identified as NZ European or Asian and over half were in their first year of university. Demographics are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of participants at baseline (n = 124).

Baseline clinical characteristics of the sample presented in Table 4 were suggestive of psychological distress on various domains. Participants exhibited moderate stress levels (against a population mean score of 14.2 (SD = 6.2) (Cohen et al. 1994). Subjective well-being scores were within ‘medium’ for satisfaction, life worth, and happiness scores (ONS4-1, ONS4-2 and ONS4-3, respectively) while anxiety scores (ONS4-4) were high (Benson et al. 2019). A WHO-5 score below 50 is suggestive of poor emotional well-being and possible depression (Topp et al. 2015)

Table 4.

Clinical characteristics at baseline (N = 124).

At baseline, Cronbach alpha coefficient for WHO-5 was 0.888; for PSS-10, 0.849; and for GAD-7, 0.831. At post-intervention, the figures were 0.872, 0.853, and 0.853 respectively.

3.2. Engagement and Adherence to the Chatbot

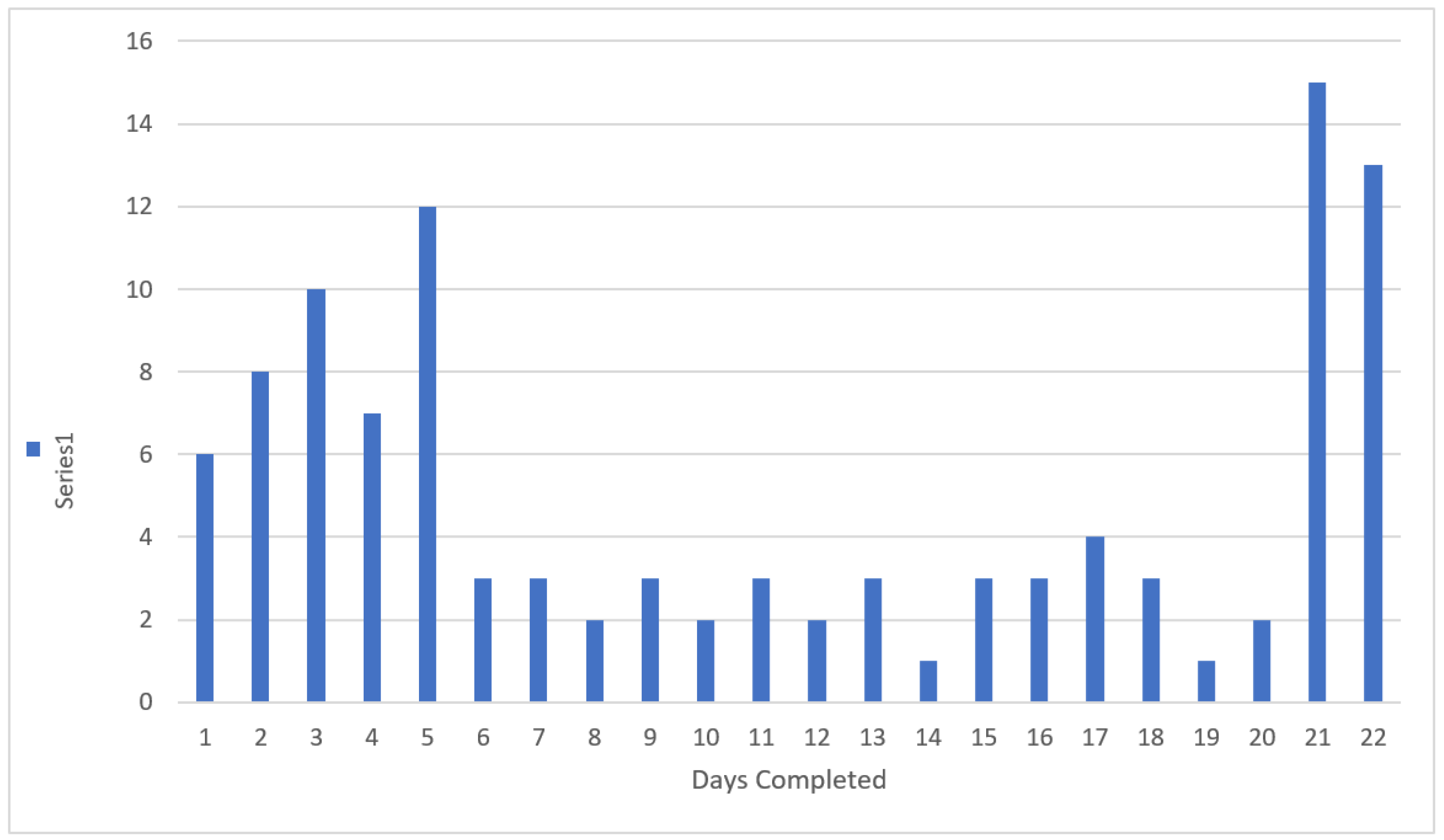

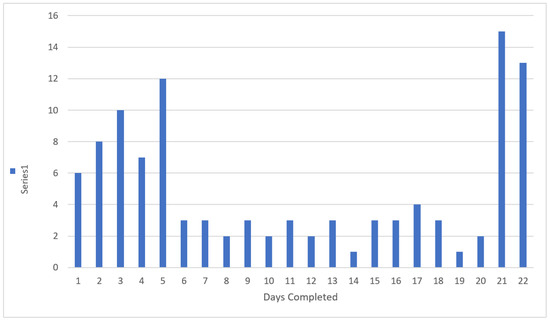

On average, participants adhered to the programme for 11 days out of the total 21-day programme (M = 11.3, SD = 7.8). Thirty participants (27.3%) adhered fully, completing all 21 days (and/or up to day 22 which was content-free); 15 (13.6%) completed between 15–20 days; 11 (10%) completed between 10–14 days; 23 (20.9%) did 5–9 days; and 25 (22.7%) did between two and four days of content. Six (5.5%) discontinued after day one. Adherence rates are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Days completed of the 21 Day Stress Detox programme. (Day 22 was ‘content-free’ and consisted of a message prompting the participant to complete the post-intervention assessment.) The average number of completed modules was 19.3 (SD = 15.3). Twenty-six percent (n = 31) completed between 30 and 51 modules and 23% engaged with fewer than five modules. One participant accessed different modules 73 times (completing several modules more than once) during the programme.

3.3. Acceptability

3.3.1. Quantitative Outcomes

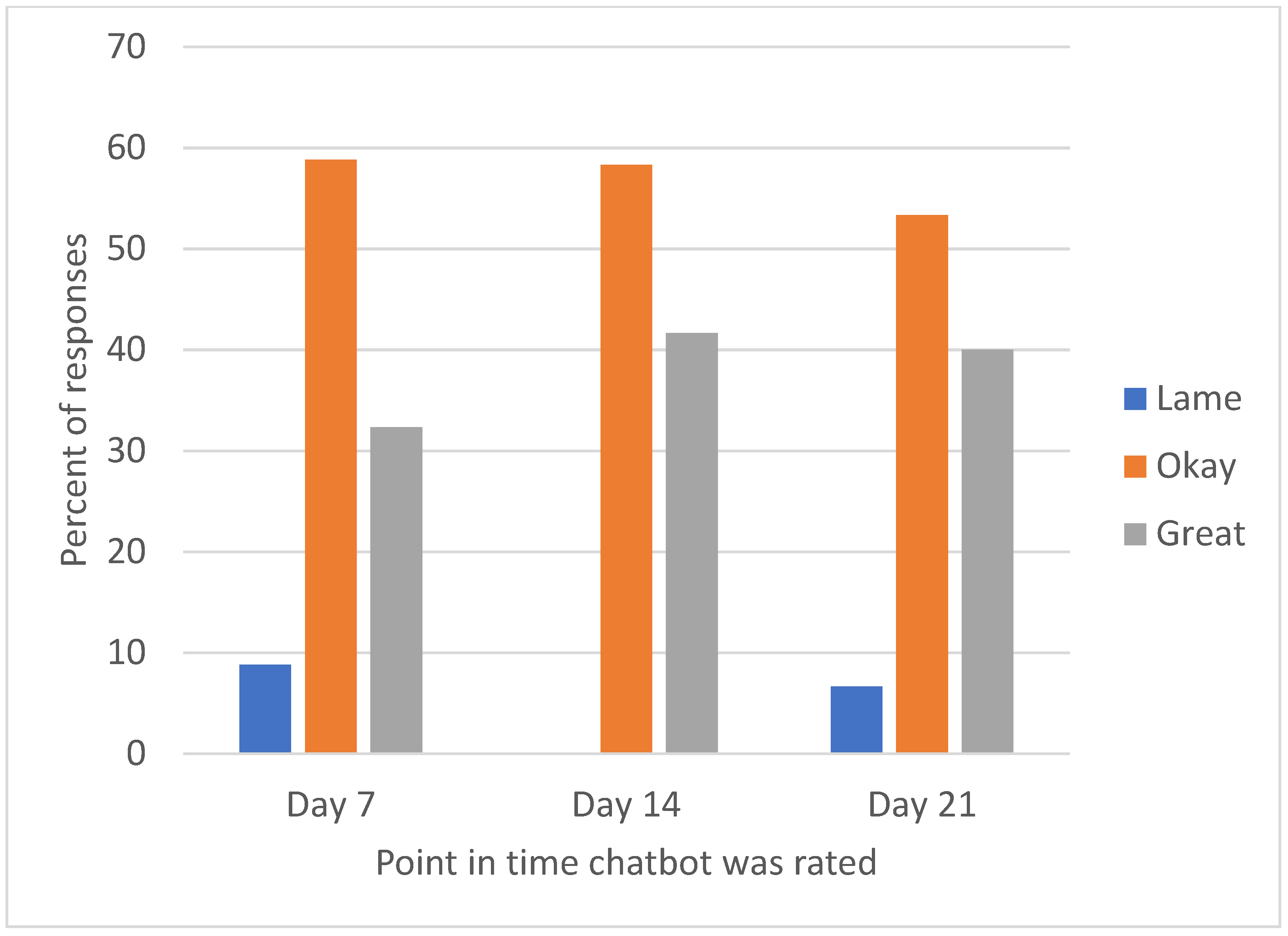

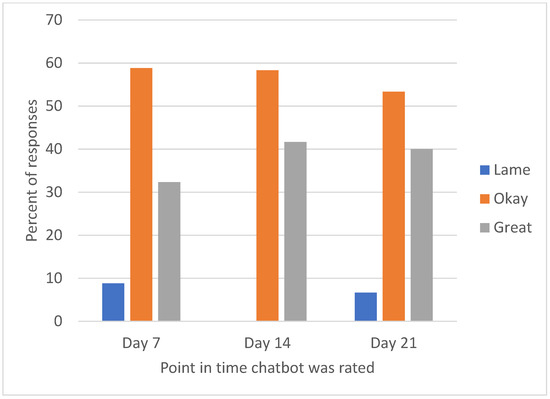

Over 90% of participants who gave a chatbot rating during the programme rated their experience as “Okay” or “Great” (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Participant rating for chatbot at three timepoints during the 21-Day Stress Detox programme. Day 7, n = 34; day 14, n = 24; day 21, n = 15.

Glitch-free interface, ease of use, and aesthetic appeal were rated highest on a satisfaction scale (Table 5).

Table 5.

Mean ratings on the Chatbot Rating Scale [range between 0 (not at all) to 4 (definitely) collected at post-intervention (day 22).

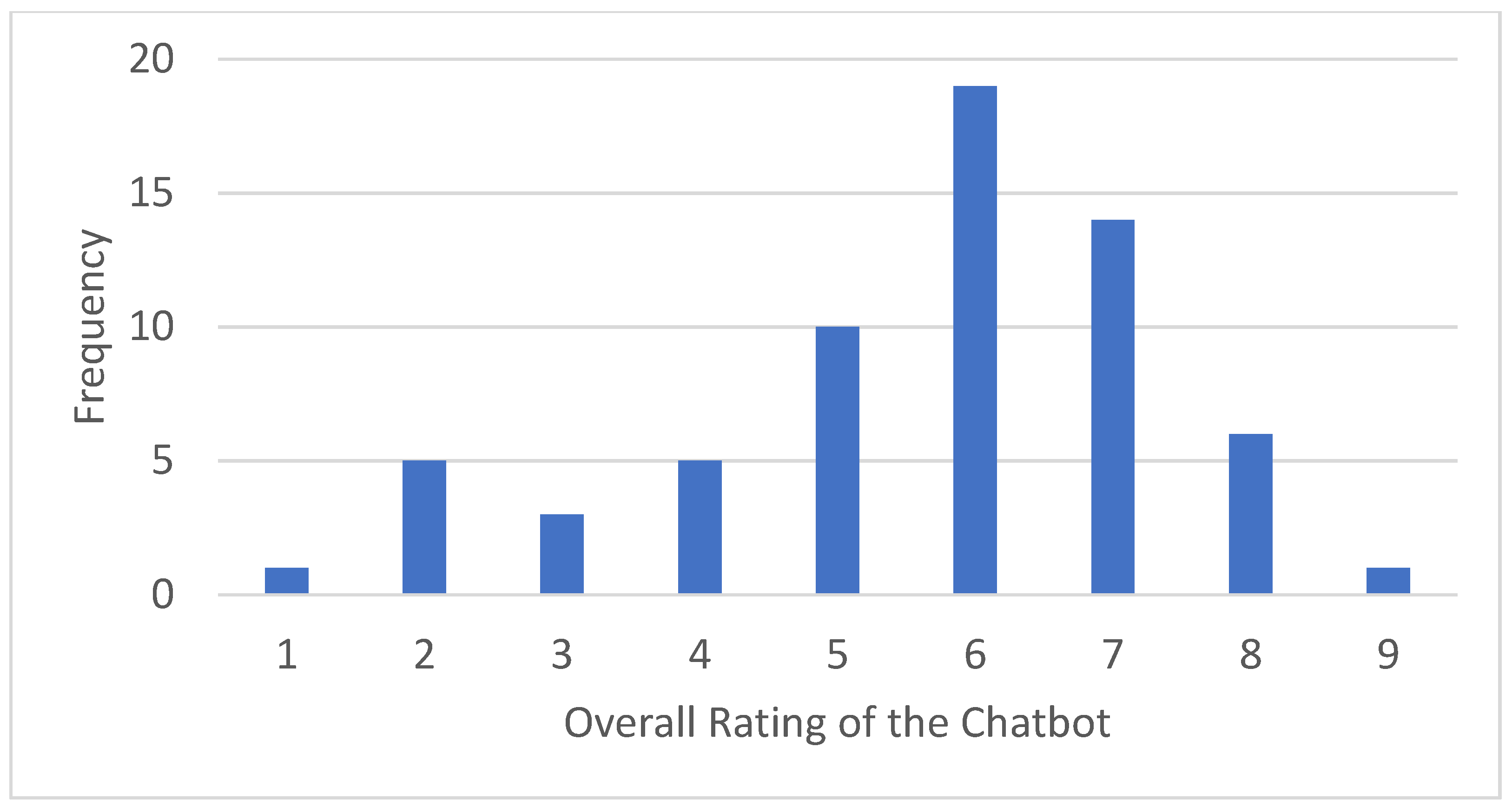

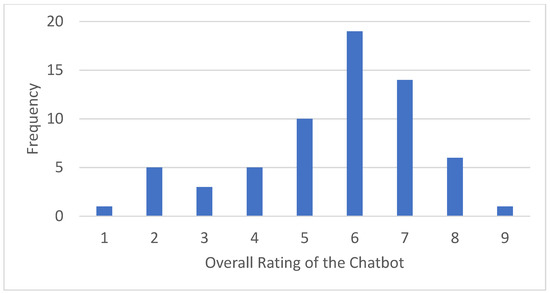

Overall, the chatbot received a mean rating of 6.61 (SD = 1.78) out of 10 (median = 7). Distribution of ratings is included in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Satisfaction rating post intervention (N=64).

3.3.2. Qualitative Feedback

Fifty-six participants provided free-text feedback about the chatbot at post-intervention in response to two questions:

- “What did you like most about the chatbot?” (most liked).

- “What did you like least about the chatbot?” (most disliked).

Free text responses were analysed using Thomas (2006) general inductive approach. Consequently, we grouped the comments into four key themes related to connection with the chatbot, convenience, and technical nature.

Theme 1: Participants most frequently commented about content in their feedback. They reflected on skills which they had learned or were reminded of, or how the chatbot stimulated their interest in learning new information. The positive reactions feedback (i.e., in response to the “most liked” question) typically gave details of specific modules perceived as helpful or enjoyable. Participants also frequently commented on the visual communication tools, for example, that the emojis and GIFs made the content more engaging and easier to relate to. However, negative feedback tended to be more general and often mentioned lack of personal relevancy, such as:

“I think Stress Detox reinforces the skill set I am already learning through therapy,”(most liked)

“The use of GIFs kept it interesting.”(most liked);

“Some of the things it talked about weren’t relevant to me or my current situation,”(most disliked); and

“I didn’t relate with the language, maybe it would be better to have a language choice,”(most disliked).

Theme 2: Users often commented on a perceived connection with the chatbot (or lack thereof). From a positive perspective, this related to a sense of alliance or even friendship that developed from the daily chats. Conversely, the negative feedback sometimes mentioned that an exchange with a chatbot may highlight feelings of loneliness or disconnection. Others felt that the chatbot was not able to understand them and they felt talked down to. The following are examples of positive and negative comments:

“I liked its friendly, outgoing nature. It was a positive addition to my day and made me feel validated,”(most liked);

“Like talking to a friend.”(most liked);

“Sometimes I wish I could be talking to a real person through text because it’s overwhelming to ring someone or talk face to face with them. Having a robot to talk to is nice but it kind of makes you feel alone sometimes,”(most disliked); and

“It didn’t listen to my preferences, and it seemed patronizing at times,”(most disliked).

Theme 3: A great deal of feedback centered on the convenience associated with using a chatbot. Frequent comments included the ease of use, accessibility, and being able to set the time of the exchanges to fit into one’s day. Interestingly, comments were often polarised with some people liking the daily ‘chats’ and others finding it repetitive and constricted, such as:

“I can use it at any time after 8. I can pause and come back to it,”(most liked);

“I liked how it prompted you to use every day.”(most liked);

“Having to do it every day felt like a chore,”(most disliked); and

“Time consuming sometimes,”(most disliked).

Theme 4: Finally, a substantial amount of feedback reflected on the technical nature. On the one hand, positive comments related to the chatbot design, interactivity, and availability through the Messenger platform. On the other hand, participants wished for more technical capability e.g., to be able to type their own responses (instead of using predetermined options) and a more nuanced range of responses back from the chatbot, for example:

“How interactive it was,”(most liked);

“How realistic it is,”(most liked);

“The responses were very limited, you couldn’t really say much,”(most disliked); and

“The same old questions every day,”(most disliked).

3.4. Clinical Efficacy

There was a statistically significant improvement pre- to post-intervention on the WHO-5, with a mean change of 7.38 (SD = 15.07; p < 0.001), and a mean change of 1.77 (SD = 4.69; p = 0.004) on the PSS-10. These changes equate to effect sizes (ES) of 0.49 and 0.38, respectively. None of the other outcome measures showed a significant change from baseline to post-intervention, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

Paired sample t-tests for each outcome measure (n = 64).

Post-hoc analyses showed no significant differential effects of the chatbot based on gender or ethnicity on any of the clinical outcomes.

Those with clinically elevated symptoms (at or above cut-off of 10 on GAD-7) at baseline (n = 25) had a significantly greater reduction in anxiety symptoms at post-intervention than those (n = 39) below the cut-off score on GAD-7 (F(1, 63) 0.67, p = 0.01). There were no other differences between pre-post change scored between the two subgroups (as shown in Table 7).

Table 7.

One-way ANOVA between change in clinical outcome and baseline anxiety on GAD-7.

4. Discussion

4.1. Principal Findings

We have demonstrated that delivering a time-limited universal stress management intervention in the form of a Facebook Messenger chatbot is feasible, acceptable, and relatively engaging for young adults. Our evidence-based content was successfully delivered using brief daily ‘chats’; close to a third of users completed the whole programme and over 40% completed over two thirds of the intervention. There were encouraging clinical outcomes of reduced stress and improved subjective well-being with good effect sizes. Qualitative feedback highlighted the helpful nature of the content, convenience, and ease of use. Some found the daily use fun while for some it was too prescriptive. Comments also suggested the need to personalise content and improve the conversational interface.

4.2. Comparisons with Prior Work

Tertiary students are known to experience psychological distress and too often not have access to appropriate support (Mojtabai et al. 2011; Ollendick et al. 2018). This study strengthens current evidence that there is a demand for digital interventions in this population; recruitment was more rapid than expected, with over 100 students registering on the study portal within the first three weeks of recruitment. Our approach of using non-clinical language and content conceptualised as a lifestyle programme may have helped to reduce barriers to seek help. Promoting mental health initiatives in a way that avoids stigmatisation is important to achieve wider access.

Our engagement rates compare well to other well-being chatbots described in literature (Gardiner et al. 2017; Greer et al. 2019). A little less than a third (27.3%) completed the full programme and 40.9% completed over half the intervention. It is evident that the intensity of engagement with our chatbot varied across the sample. The usage pattern appears to follow a bimodal distribution previously observed in a study by Inkster et al. (2018) of the chatbot Wysa suggesting there are ‘low’ and’ high’ engagers in these types of interventions. This may be due to users tailoring the programme to their needs, which is an important part of the acceptability model of digital well-being tools. While online interventions have been sometimes singled out as having poor adherence (Fleming et al. 2018), it is worth noting that adherence to traditional face-to-face therapy varies a lot and is less than optimal. A large review by Swift and Greenberg (2012) showed that at least one in five clients drop out of therapy prematurely. Others suggest that no more than a third of patients return after the first session (Barrett et al. 2008).

Studies on chatbots to date have reported fairly high satisfaction and user acceptability (Inkster et al. 2018). Our study is no exception, with almost two thirds rating their overall satisfaction as high (7/10 or more). Written feedback provided plentiful examples of how much some enjoyed the content, connection with the chatbot, and ease of access. This resonates with the studies by Fitzpatrick et al. (2017) and Inkster et al. (2018) which also reported that chatbots were convenient and that people empathise with conversational agents. Interestingly, we found certain aspects of the chatbot to be polarising, with participants often commenting on the same thing with opposite opinions. Clearly, one size does not fit all and what is engaging to one person can be off-putting to another. Future chatbot developers should aim to increase customisation and to personalise as many elements of the delivery as possible, based on user preference.

We have found evidence of partial efficacy, similar to a number of other chatbots (Carey et al. 2016). While we found a reduction in stress and significant increase in subjective well-being, there was no change in anxiety symptoms. This may be explained by the fact that the chatbot was promoted as a stress management programme and offered universally. Overall, our participants had relatively low anxiety levels at the start of the study (as expected in a non-clinical sample); however, those who had elevated symptoms experienced a significant reduction compared to those with no clinical symptoms. This reinforces the merits of universal delivery of mental health interventions as it is able to capture at-risk subgroups while enhancing the well-being of a broader population. It is worth noting that the study period targeted a time of year when we would expect to see an increase in anxiety and stress due to the pressure of end-of -year exams. It is possible that the 21-Day Stress Detox chatbot helped to keep anxiety levels at bay.

4.3. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

One of the key successes of this project is that we have built a custom-design chatbot capable of delivering support related to stress and well-being to young adults in a form that is acceptable to them. This has been achieved in a short amount of time at a low cost and could be replicated for different populations. Feedback from users suggests that non-clinical content and delivery style (friendly style/tone, jokes, metaphors, GIFs, and motivational quotes) increased accessibility to the therapeutic content. Our findings demonstrate that evidence-based content can be delivered using conversational chatbots to offer first tier of psychological support.

As with all studies, there are a number of limitations. Firstly, as this was an open single-arm, uncontrolled study, our conclusions about efficacy need to be made with caution. Future studies should include a comparison arm or even account for the possible placebo effect. Follow up is also recommended to establish the longer-term impact of the intervention. Furthermore, implementing interventions in the ‘real world’ differs from the experimental stage and thus time will tell how effective chatbots are once available to the public. The evidence to date suggests that they are popular and well-liked so the interest and investment in this technology is warranted

Finally, our study was carried out in one university located in a large urban centre in New Zealand. As is often the case, we had an over-representation of females and the ethnic makeup of the sample does not match the greater NZ society (in particular we had an under-representation of Māori and Pacific Island students). Consequently, our results may not generalise to other contexts, and further exploration needs to include a more diverse range of users.

5. Conclusions and Future Directions

In 2020, over 2.5 billion people worldwide owned a smartphone (Rowland et al. 2020). Potentially, each of these devices provides the opportunity to connect with and deliver brief well-being support to many for whom any mental health support would otherwise be out of reach. Despite increasing interest in digital well-being tools from service users and providers, there remains uncertainty over how best to utilise technology to deliver care (Rowland et al. 2020). Our study demonstrated that there is a place for innovative technology, such as chatbots, in providing access to universal well-being support. Our low-intensity, time-limited intervention was delivered via a chatbot using an existing Messenger service that fitted well into daily habits of young adults. Future work should include greater emphasis on more customizable content and sophisticated/adaptive conversational interface.

One of the major challenges for researchers is to keep up with the rapid pace of technology. For example, since completing this study, Facebook changed its policy regarding daily notifications from chatbots, prompting us to move our intervention from Facebook Messenger to a native app. While, traditionally, the next step would be to establish clinical efficacy, doing it in a randomized controlled trial setting risks falling behind technology even further. Assessing utility and impact in the ‘real world’ may yield valuable insights more quickly. Unlike some interventions, our chatbot system allows for rapid iteration of content and, therefore, we can evolve and optimize it quickly in response to user feedback. It is apparent that, in the future, content should be more personalisable to suit individual needs and communication styles. Work is also required on the conversational interface to make it more adaptive and sophisticated for increasingly discerning audiences.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, R.W., K.S. & S.N.M.; methodology, R.W. & K.S.; software, C.H.-Q.; formal analysis, R.W., C.F. & S.H.; writing—original draft preparation, R.W., K.S., S.H., & S.N.M.; writing—review and editing, R.W., K.S., S.H., & S.N.M.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, R.W.; funding acquisition, S.N.M., K.S., S.H. & C.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was carried out as part of R.W.’s Master of Science in Psychology project. The funding for the development of the software engine supporting the delivery of 21 Day Stress Detox was obtained from the Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, A Better Start, E Tipu E Rea, grant number UOAX1511 (ABST1002).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved on 18 June 2019, by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (protocol number 023234).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to the Ethics agreement (i.e., participants had consented to have their data accessed only by the named researchers).

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the study participants who generously contributed their time to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

At the time of writing this manuscript, the authors have no conflict of interest to declare. The intellectual property of The 21 Day Stress Detox chatbot is owned by UniServices Ltd, the commercial arm of the University of Auckland.

References

- Barrett, Marna S., Wee-Jhong Chua, Paul Crits-Christoph, Mary Beth Gibbons, and Don Thompson. 2008. Early withdrawal from mental health treatment: Implications for psychotherapy practice. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training 45: 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bech, Per, Lis Raabaek Olsen, Mette Kjoller, and Niels Kristian Rasmussen. 2003. Measuring well-being rather than the absence of distress symptoms: A comparison of the SF-36 Mental Health subscale and the WHO-Five Well-Being Scale. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 12: 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benson, Tim, Joe Sladen, Andrew Liles, and Henry W. W. Potts. 2019. Personal Wellbeing Score (PWS)—A short version of ONS4: Development and validation in social prescribing. BMJ Open Qual 8: e000394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carey, Timothy A., Jennifer Haviland, Sara J. Tai, Thea Vanags, and Warren Mansell. 2016. MindSurf: A pilot study to assess the usability and acceptability of a smartphone app designed to promote contentment, wellbeing, and goal achievement. BMC Psychiatry 16: 442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, Sheldon, Tom Kamarck, and Robin Mermelstein. 1994. Perceived stress scale. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists 10: 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Fava, Giovanni A., Chiara Rafanelli, Manuela Cazzaro, Sandra Conti, and Silvana Grandi. 1998. Well-being therapy. A novel psychotherapeutic approach for residual symptoms of affective disorders. Psychological Medicine 28: 475–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feicht, T., M. Wittmann, G. Jose, A. Mock, E. von Hirschhausen, and T. Esch. 2013. Evaluation of a seven-week web-based happiness training to improve psychological well-being, reduce stress, and enhance mindfulness and flourishing: A randomized controlled occupational health study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013: 676953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, Kathleen Kara, Alison Darcy, and Molly Vierhile. 2017. Delivering Cognitive Behavior Therapy to Young Adults With Symptoms of Depression and Anxiety Using a Fully Automated Conversational Agent (Woebot): A Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Ment Health 4: e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, Theresa, Lynda Bavin, Mathijs Lucassen, Karolina Stasiak, Sarah Hopkins, and Sally Merry. 2018. Beyond the trial: Systematic review of real-world uptake and engagement with digital self-help interventions for depression, low mood, or anxiety. Journal of Medical Internet Research 20: e9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, M. K., E. Crome, M. Sunderland, and V. M. Wuthrich. 2017. Perceived needs for mental health care and barriers to treatment across age groups. Aging & Mental Health 21: 1072–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuchs, Carilyn Z., and Lynn P. Rehm. 1977. A self-control behavior therapy program for depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 45: 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gardiner, Paula M., Kelly D. McCue, Lily M. Negash, Teresa Cheng, Laura F. White, Leanne Yinusa-Nyahkoon, Brian W. Jack, and Timothy W. Bickmore. 2017. Engaging women with an embodied conversational agent to deliver mindfulness and lifestyle recommendations: A feasibility randomized control trial. Patient Education and Counseling 100: 1720–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Greer, Stephanie, Danielle Ramo, Yin-Juei Chang, Michael Fu, Judith Moskowitz, and Jana Haritatos. 2019. Use of the Chatbot “Vivibot” to Deliver Positive Psychology Skills and Promote Well-Being Among Young People After Cancer Treatment: Randomized Controlled Feasibility Trial. JMIR mHealth and uHealth 7: e15018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulliver, Amelia, Kathleen M. Griffiths, and Helen Christensen. 2010. Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 10: 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gustavson, Kristin, Ann Kristin Knudsen, Ragnar Nesvåg, Gun Peggy Knudsen, Stein Emil Vollset, and Ted Reichborn-Kjennerud. 2018. Prevalence and stability of mental disorders among young adults: Findings from a longitudinal study. BMC Psychiatry 18: 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holt-Quick, Chester, Jim Warren, Karolina Stasiak, Ruth Williams, Grant Christie, Sarah Hetrick, Sarah Hopkins, Tania Cargo, and Sally Merry. 2021. A chatbot architecture for promoting youth resilience. In Studies in Health Technology and Informatics. pp. 99–105. Available online: https://minerva-access.unimelb.edu.au/bitstream/handle/11343/280661/SHTI210017.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Huckins, Jeremy F., Alex W. DaSilva, Weichen Wang, Elin Hedlund, Courtney Rogers, Subigya K. Nepal, Jialing Wu, Mikio Obuchi, Eilis I. Murphy, and Meghan L. Meyer. 2020. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 22: e20185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkster, Becky, Shubhankar Sarda, and Vinod Subramanian. 2018. An Empathy-Driven, Conversational Artificial Intelligence Agent (Wysa) for Digital Mental Well-Being: Real-World Data Evaluation Mixed-Methods Study. JMIR mHealth uHealth 6: e12106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Wai Tat Chiu, Olga Demler, and Ellen E. Walters. 2005. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry 62: 617–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kessler, Ronald C., G. Paul Amminger, Sergio Aguilar-Gaxiola, Jordi Alonso, Sing Lee, and T. Bedirhan Ustun. 2007. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 20: 359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, Ronald C., Maria Petukhova, Nancy A. Sampson, Alan M. Zaslavsky, and Hans-Ullrich Wittchen. 2012. Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 21: 169–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lattie, Emily G., Elizabeth C. Adkins, Nathan Winquist, Colleen Stiles-Shields, Q. Eileen Wafford, and Andrea K. Graham. 2019. Digital Mental Health Interventions for Depression, Anxiety, and Enhancement of Psychological Well-Being Among College Students: Systematic Review. Journal of Medical Internet Research 21: e12869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Linardon, Jake, Pim Cuijpers, Per Carlbring, Mariel Messer, and Matthew Fuller-Tyszkiewicz. 2019. The efficacy of app-supported smartphone interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry 18: 325–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MHA National. 2021. COVID-19 and Mental Health: A Growing Crisis. Available online: https://mhanational.org/sites/default/files/Spotlight%202021%20-%20COVID-19%20and%20Mental%20Health.pdf (accessed on 20 October 2021).

- Ministry of Health. 2017. Ethnicity Data Protocols. Wellington: Ministry of Health. [Google Scholar]

- Mojtabai, Ramin, Mark Olfson, Nancy A. Sampson, Robert Jin, Benjamin Druss, Philip S. Wang, Kenneth B. Wells, Harold A. Pincus, and Ronald C. Kessler. 2011. Barriers to mental health treatment: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Psychological Medicine 41: 1751–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Oakley Browne, Mark A., J. Elisabeth Wells, Kate M. Scott, and Magnus A. McGee. 2006. Lifetime prevalence and projected lifetime risk of DSM-IV disorders in Te Rau Hinengaro: The New Zealand Mental Health Survey. The Australian and New Zealand journal of psychiatry 40: 865–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ollendick, Thomas H., Lars-Göran Öst, and Lara J. Farrell. 2018. Innovations in the psychosocial treatment of youth with anxiety disorders: Implications for a stepped care approach. Evidence Based Mental Health 21: 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, Vikram, Alan J. Flisher, Sarah Hetrick, and Patrick McGorry. 2007. Mental health of young people: A global public-health challenge. The Lancet 369: 1302–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2002. Two Decades of Developments in Qualitative Inquiry: A Personal, Experiential Perspective. Qualitative Social Work 1: 261–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberti, Jonathan W., Lisa N. Harrington, and Eric A. Storch. 2006. Further psychometric support for the 10-item version of the perceived stress scale. Journal of College Counseling 9: 135–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, Simon P., J. Edward Fitzgerald, Thomas Holme, John Powell, and Alison McGregor. 2020. What is the clinical value of mHealth for patients? Npj Digital Medicine 3: 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schegloff, Emanuel A. 1968. Sequencing in Conversational Openings1. American Anthropologist 70: 1075–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanahan, Michael J. 2000. Pathways to Adulthood in Changing Societies: Variability and Mechanisms in Life Course Perspective. Annual Review of Sociology 26: 667–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silfvernagel, Kristin, Carolina Wassermann, and Gerhard Andersson. 2017. Individually tailored internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for young adults with anxiety disorders: A pilot effectiveness study. Internet Interventions 8: 48–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spitzer, Robert L., Kurt Kroenke, Janet B. W. Williams, and Bernd Löwe. 2006. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: The GAD-7. Archives of Internal Medicine 166: 1092–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Staehr Johansen, K. 1998. The Use of Well-Being Measures in Primary Health Care—the DepCare Project. target 12, E60246. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Google Scholar]

- Swift, Joshua K., and Roger P. Greenberg. 2012. Premature discontinuation in adult psychotherapy: A meta-analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 80: 547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, John M. 2015. Psychometric analysis of the Ten-Item Perceived Stress Scale. Psychological Assessment 27: 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas, David R. 2006. A General Inductive Approach for Analyzing Qualitative Evaluation Data. American Journal of Evaluation 27: 237–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tinkler, Lucy, and Stephen Hicks. 2011. Measuring subjective well-being. London: Office for National Statistics 2011: 443–55. [Google Scholar]

- Topp, Christian Winther, Søren Dinesen Østergaard, Susan Søndergaard, and Per Bech. 2015. The WHO-5 Well-Being Index: A systematic review of the literature. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 84: 167–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaidyam, Aditya Nrusimha, Hannah Wisniewski, John David Halamka, Matcheri S. Kashavan, and John Blake Torous. 2019. Chatbots and conversational agents in mental health: A review of the psychiatric landscape. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 64: 456–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VanderWeele, Tyler J., Claudia Trudel-Fitzgerald, Paul Allin, Colin Farrelly, Guy Fletcher, Donald E. Frederick, Jon Hall, John F. Helliwell, Eric S. Kim, William A. Lauinger, and et al. 2020. Current recommendations on the selection of measures for well-being. Preventive Medicine, 106004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warren, Jim, Sarah Hopkins, Andy Leung, Sarah Hetrick, and Sally Merry. 2020. Building a Digital Platform for Behavioral Intervention Technology Research and Deployment. In Paper presented at the Proceedings of the 53rd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Wailea, HI, USA, January 7. [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz, Petra H., and Roland von Känel. 2017. Psychological stress, inflammation, and coronary heart disease. Current Cardiology Reports 19: 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Henry, Dever M. Carney, Soo Jeong Youn, Rebecca A. Janis, Louis G. Castonguay, Jeffrey A. Hayes, and Benjamin D. Locke. 2017. Are we in crisis? National mental health and treatment trends in college counseling centers. Psychological Services 14: 407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).