1. Introduction

This article investigates the possible interrelationship between the rhetoric of Abu Musa’ab Al-Zarqawi and the fragmentation-grievances dynamics in post “Operation Iraqi Freedom” times; indeed, analyzing language lies at the heart of this research endeavor. The MENA region is one where grievances and factionalism plays a major role in violent conflicts (

Kivimäki 2021); here we use Iraq’s case vis a vis its spike in terrorist-related deaths after the 2003 war. We analyze in-period statements of Abu Musa’ab Al-Zarqawi and use two social psychology theories in highlighting how such factionalism and grievances are weaponized for the purpose of inflaming such violence. This way we provide compelling evidence of the importance of factionalism and grievances for terrorist rhetoric, and show, in detail, how that is the case.

In a region infamous for its instability, Iraq has always been one of the most unstable countries, especially since Saddam Hussein took to power in 1979. Since then, the country has suffered consecutive catastrophes: two gulf wars followed by paralyzing United Nations sanctions left it in shatters. Another factor for Iraq’s instability lies in the innermost dynamics of Iraqi society. Saddam’s regime was one heavily reliant on elite ethnicity: in fact, all of Iraq’s rulers since the 1920s were from the Sunni Arab community, itself a minority in the country (

Jaboori 2013). Hussein’s regime didn’t stop at politically marginalizing other factions of Iraqi society, rather, on multiple occasions, it chose to wage war against them. Examples of which are the 1988 offensive against Kurdish forces allied with Iran during the Iran–Iraq War, and the 1990 rebellion by both Kurds in the north and the far outnumbering Shias in the south (

Pirnie and O’Connell 2008).

In turn, this morphed into an active marginalization of the Sunni community following the Iraq War in 2003 and the resulting toppling of Hussein’s regime and, thereby, his Sunni Arab elite of regime figures. At the time, Sunni Arabs largely boycotted the first elections, which naturally resulted in an overwhelming win for the Shia majority. They, however, did take part in the 2005 election when they managed to achieve evident success in their regions, but they were, ultimately, denied influential positions that were held by Shia and Kurdish members (

Jaboori 2013). Such an environment of frustration ignited an insurgency of massive scale; Sunni extremist groups launched bombing attacks against U.S. troops as well as Shia populations (

Pirnie and O’Connell 2008). The latter, in turn, made sure to take revenge by terrorizing Sunni civilians and utilizing murder and intimidation in order to force them to leave their homes (

Pirnie and O’Connell 2008). The situation concerning Iraqi Sunnis remains concerning, as Renad

Mansour (

2016) put it, “Iraqi Sunnis are disillusioned by the monopolization of power by a few Shia elite and the impunity of perceived sectarian Shia militias that are part of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF).”

Following “Operation Iraqi Freedom” in 2003, a fragmented, fragile, and volatile Iraq was left a fertile land for extremists to fester and pursue their agendas. Of these extremists, none was more influential than a Jordanian Al-Qaida member named Abu Musa’ab Al-Zarqawi. He was, perhaps, the key leader of the Arab Sunni insurgency against U.S. forces and the Shia-dominated Iraqi government. Zarqawi’s importance in this study stems from the fact that, in a country plagued by all kinds of armed conflicts, Iraq is by far the country with the highest rate of terrorism deaths to conflict deaths in the world. The attached graphs herein show the saliency of terrorist attacks in the context of a civil war, in

Figure 1. We chose to highlight the fatalities that took place the years spanning before the start of the War and the year following Zarqawi’s death.

Born in 1966 of Jordanian Palestinian parents in the rough town of Az Zarqa, Zarqawi was believed to had been radicalized in prison where he spent time for crimes of drug possession and sexual assault, amongst others (

Michael 2007). Later, he traveled to Afghanistan in 1989 where he started his involvement with Islamism. After, he headed back to Jordan and started a jihadist organization and ended up being sentenced to prison for that reason and for possession of illegal weapons (

Michael 2007). Zarqawi later moved to Iraq and became a key figure in the Iraq war, even before the war began, for his mere presence was one of the major justifications for the war, as U.S. Secretary Powell clearly stated in his famous U.N. speech in 2003. In fact, Zarqawi was mentioned twenty-one times in just one section of that speech in the attempt to link Saddam’s regime with Al-Qaida (

Breslow 2016). This, in turn, helped Zarqawi’s rise as a public figure (

Warrick 2016). The following years witnessed his organization’s ascendance to the Iraqi scene, accompanied by sectarian mobilization and brutal tactics that caused him to be perceived as an extremist by no other than Bin Laden (

Patterson 2016). Nevertheless, he led Al-Qaida’s affiliate in Iraq (AQI), which preferred to focus on the “near enemy” of whom Shia Muslims were paramount; such was aided by reference to the fatwas of the famous medieval scholar Ibn Taymayyah (

Celso 2015, p. 24). Following his death, his successors slowly evolved into forming what is now known as ISIS (

Warrick 2016). Indeed, Zarqawi may very well be considered the father of ISIS (

Patterson 2016).

In this article we analyze how factionalism and grievances lead to conflict by focusing on the very processes that Zarqawi utilized to mobilize his supporters into violence. This way the intention is to move from the correlative relationship between factionalism and organized violence on the one hand, and grievances and violence on the other (

Kivimäki 2021), to the analysis of the mechanism in which factionalism and grievances are being translated into organized violence. The impact of external intervention, also specific for the causal complex in MENA according to Kivimäki, is also included in the examination of this article.

The focus of this article is on one of the most violent countries in the Middle East, Iraq, during the period of 2003 to 2006, when fatalities of organized violence had sharply increased. We will show how Iraq’s post-war environment created a perfect storm for Zarqawi to capitalize on existing fractions within the Iraqi society and mobilize Arab Sunnis in the country against American troops as well as their fellow Iraqis. In doing so, we utilize the Integrated Threat and the Social Identify Theories, through which an analysis of Zarqawi statements is presented. This analysis will show the mechanism by which Zarqawi made use of, as well as exacerbated, existing factionalism, and how said factionalism was formulated in Zarqawi’s rhetoric. We show, through careful analysis of Zarqawi’s statements, a rhetoric empowered by the political chaos left by the U.S. invasion of a country blessed, as well as cursed, by a rich and complex history from which the invading powers were mostly blind.

The first included chart shows a success story, so to speak, of terrorism in a country that, at the time, suffered immense violence and instability. Between the time that the Coalition’s forces took over Iraq, and the time Zarqawi died, there was an evident rise of terrorism-related deaths. Not long before the war, deaths by terrorist acts were virtually non-existent. After the war, these deaths spiked to constitute up to 4% of total deaths by 2007. To put this into perspective, the country’s conflict deaths in the same time frame ranged, approximately, between 8% and 15%. This far exceeds the world average, and for comparison, the next country on that chart, Palestine, peaked at 1% in 2003 (

Figure 1). The second chart is three dimensional with the time dimension, from 2002 to 2007, indicated by the one-directional arrow; it illustrates the changes in terrorism and conflict deaths with time. It shows that while conflict deaths moved back and forth (declining in 2004 and 2007), fatalities of terror increased consistently following the U.S.-led intervention (

Figure 2). Both graphs have been created using a portal provided by Our World in Data. Data on conflict deaths are sourced from The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) dataset, while data on terrorist incidents are sourced from the data from the Global Terrorism Database (GTD) dataset.

Here we outline GTD’s definition of terrorism as “The threatened or actual use of illegal force and violence by a non-state actor to attain a political, economic, religious, or social goal through fear, coercion, or intimidation” (

Global Terrorism Database (GTD) 2021). Such a significant proportion of terrorism deaths in Iraq highlight the imperative necessity for studying terrorism in that country; the dialectic between fragmentation and grievances on the one hand and terrorism on the other implores us to investigate that two-way relationship between reality and rhetoric. Inasmuch as terrorist leaders, like Zarqawi, seek to create their preferred reality, they, in turn, take advantage of the existent reality by way of building on, and then manipulating, it. This article seeks to expose that very dialectic, to expose how Zarqawi took advantage of existing fragmentations and grievances in order to plant seeds for more.

2. Theoretical Framework

This article builds on two social psychology theories, Integrated Threat Theory and Social Identity Theory, as a building block in establishing a framework for analyzing discriminatory rhetoric of extremists like Zarqawi. For factionalism to be converted into conflict, one must establish rhetorical links between the two in order to successfully influence the targeted audience of said rhetoric.

Any discussion of the Iraqi civil war, and the accompanying violent-extremism, cannot be adequately understood without minding the Sunni-Shia divide, which is a key element of this research; however, an extensive analysis of this phenomenon goes beyond the scope of this article. In fact, it has been tackled repeatedly before: our research focuses on the dynamics between the allies/Shia-dominated Iraqi government vs. Zarqawi and his organization to which civilians often fall victim; that corroborates

Finnbogason et al.’s (

2019) claim that “a large degree of the violence across the Shia-Sunni divide is clearly dominated by state-based conflicts. It is driven by centralised actors, primarily states, rebel groups, and militias rather than communities” (p. 47). For more on the Sunni-Shia divide and its role in the region’s conflicts see also (

Svensson 2007;

Cheterian 2021;

Ahmed 2012;

Abdo 2017;

Larsson 2016). Here we add to the existing literature by highlighting how this divide is aggravated by Iraq’s post-war policies and measures, as well as capitalized by Zarqawi’s rhetoric.

Social Identity Theory explains the ease with which individuals can ascribe themselves to an

in-group that stands unique from

out-groups. It is defined as “a social psychological theory of identity formation that privileges the role of large group identities in forming individuals’ concepts of self. It has been used, in particular, to examine the formation and forms of adherence to national and ethnic groups.” (

Calhoun 2002). It was pioneered by Henry Tajfel in 1970s and 1980s and came as a result of years of academic curiosity regarding how individuals develop their social as well as individual identities, and, therefore, the relationship between that individual and society at large (

Baker 2012, p. 130). For

Tajfel and Turner (

2004), intergroup relations are dominated by bias towards the

in-group; the mere identification with an

in-group results in such bias, and, similarly, “the mere awareness of the presence of an out-group is sufficient to provoke intergroup competitive or discriminatory responses on the part of the in-group.” (

Tajfel and Turner 2004, p. 281).

Integrated Threat Theory (ITT) adds to Social Identity Theory (SIT) by outlining the importance that

perceived threats have over that intergroup dynamic. A belief that one’s culture, for example, is under

threat from another poses a serious impediment in the face of cementing a healthy relationship between these cultures, affecting many aspects of interaction between them, and even encouraging prejudice between members of these different cultures (

Stephan et al. 2000, p. 240). The theory has been used in multiple studies, and was updated by Stephan and Renfro to revolve around two key types of threats:

realistic threat and

symbolic threat (

Stephan et al. 2002).

Realistic threats are those concerned with the wellbeing of the

in-group such as political and economic power, while

symbolic threats are concerned with the

in-groups’ values, beliefs, or worldviews;

realistic threats are tangible unlike

symbolic ones, and both, importantly, may only be

perceived and not necessarily actual (

Stephan et al. 2002).

The two theories work together by way of complementation; once group identity is established, and once out-groups are identified, then it becomes remaining the connection between these out-groups and their perceived threat towards the in-group. Zarqawi didn’t simply identify the groups he identified as enemies, but rather went to great lengths in establishing why and how said groups are dangerous to his constituency. Together, these two theories provide a viable framework for studying the link between societal fragmentation and terrorism. Employing them will highlight the different out-groups that pose as a threat to Zarqawi’s in-group, in addition to the types of such threats. Said analysis is then further utilized to illustrate the relationship between changes on the ground and changes in the rhetoric.

We sought to operationalize the Social Identity Theory and the Integrated Threat Theory through the breaking down of SIT and ITT into their basic elements. By searching for, and coding such elements, we draw a picture of factionalism in Iraq as reflected and developed by Zarqawi. Once this picture is clearly drawn, a subsequent analysis is provided to shed light on how Zarqawi took advantage of a divided society in order to plant the seeds of violence and instability: this picture will manifest the different out-groups (enemies) in the focus of Zarqawi’s rhetoric, as well as the different threats posed to Zarqawi’s de facto in-group.

Before we commence, however, it is important to tackle the question of the historical roots of said factionalism. Our analysis of Zarqawi’s rhetoric is a window through which we seek to understand the weaponization of existing factionalism in creating a narrative of agency and emergency; Zarqawi sought to speak for his in-group and portray the emergency that is the various threats he ascribed to the different out-groups in the country. Such narrative is, at least partially, yet importantly, ingrained in the collective memory of the peoples who live in the region, as well as in the belief system that the likes of Zarqawi adopt. In the next section, we show the conceptual ground upon which Zarqawi built his rhetoric; first, we outline the historical, as well as the theological, background of said rhetoric, and then we provide evidence of the relation between the historical/theological and the very words Zarqawi used, in our database.

3. Methodology

As stated in our introduction, the analysis of language lies at the core of this article; whether it’s

threats or

out-groups, inasmuch as the language is consistent in its choice of terminology, the rhetoric associated therewith is comprehensible to the audience. Discourse Historical Analysis recognizes language as a method of social practice; it seeks to “transcend the pure linguistic dimension and to include, more or less systematically, the historical, political, sociological and/or psychological dimension in the analysis and interpretation of a specific discursive occasion” (

Reisigl and Wodak 2005, p. 35). One of the original purposes of DHA, in fact, was to identify discriminatory discourses such as those racist or ethnicist (

Reisigl and Wodak 2005, p. 44). We will highlight the historical-theological bases upon which groups or individuals can be outcast in Islam; those lay the building block for Zarqawi’s discriminatory rhetoric against other Muslims. We link the linguistic tools to their historiological-theological roots: Zarqawi’s rhetoric is to be proven as based on two main pillars; one is focused on the theological justification of demonizing certain Muslims, mainly Shias, building on the concept of the

munafiq (hypocrite). The other pillar is one that links the aforementioned theological justifications with a historical narrative concerning the

out-groups under study.

While the qualitative DHA illuminates the internal logic of the rhetoric under study, it is less helpful when it comes to exploring how different themes develop in time, nor does it help with exploring the relevant importance of different threats and out-groups. It is here where this article seeks the aid of computer-assisted textual analysis.

The computer-assisted textual analysis method utilized NVivo as a tool for providing an analysis of the development of Zarqawi’s rhetoric through time; threats and out-groups are presented in a time scale showing their varied degrees of saliency at different points of time.

Finally, a dialectical analysis focused on the interaction between Zarqawi’s discourse, on the one hand, and the non-discursive developments of the intervention, as well as the allied discourse on counterinsurgency, on the other.

Collecting reliable terrorist-related data can, needless to say, be a rather arduous task. Our textual data was taken from the most reliable source we can find where such materials are available:

Archive.org. This website is a non-profit organization and is one of the internet’s most renowned libraries; it was founded in 1996 by Brewster Kahle and holds twenty petabytes of data which includes web pages, books, audio and video recordings, and software programs, amongst others (

InternetArchive.org n.d.). There exists a collection of Zarqawi statements, many of which are transcripts from video or audio statements that are also available on the website, making them easy to verify. In total we had forty-two statements from which we included all statements issued in the studied time period between 2003 and 2006, all except ones of personal or apolitical nature, leaving us with thirty- seven statements.

1 We endeavored to find the best sources for Zarqawi rhetoric, and this material was the most complete and reliable we could find.

Inasmuch as we investigate the role of factionalism in creating violence and volatility in Iraq, we operationalize these theories by breaking them down to their basic elements. These elements are sought and coded in a database constituted of thirty- seven Zarqawi statements issued in a time period starting from the aftermath of the Iraq War in 2003 to the time of Zarqawi’s death in 2006. In so doing, we distinguish the different

out-groups who posed threats to Zarqawi’s

in-group (Sunnis in general and Sunni Arabs in particular) as well as the types of

threats per se. Furthermore, we investigate the development of said concepts through time and in relation to political developments on the ground (see

Supplementary Materials).

With the help of NVivo, a computer qualitative data analysis software package, we carefully analyze statements by Zarqawi. Those statements were chosen to reflect Zarqawi’s active years in Iraq, therefore neither statements outside that time frame, nor letters of personal nature were included, leaving us with thirty- seven statements. We chose to analyze the documents in their original version, in Arabic, providing a purer engagement with the rhetoric in question; this spares us the unfortunate loss, as well as change, of meaning that results from translating any text. Analyzing the texts in their native Arabic shall provide a unique advantage over other studies that depend on translated texts.

The statements came either as transcripts of video or audio statements, or as written statements in their original form. The total amounted to 407 full-size pages, each of them was read and scanned for the relevant nodes. Each of them was analyzed and coded on NVivo, which left us with a rich database that we’re discussing next. The coding process of these documents distinguished six “nodes,” four of which were out-groups while the other two were two types of

threat. These nodes are:

| Enemy | Description |

| Kurds | An out group that is present yet far from salient. |

| Local Rulers | Here are references to authorities, political leaders, or political regimes. |

| Rawafid | “Rawafid” mainly means Shia, and it is certainly the case in most of the coded documents; the word meaning “those who refuse. Derogatory term historically applied by the Sunnis to describe the Shiis, who refused to accept the early caliphate of Abu Bakr, Umar, and Uthman as legitimate.” (The Oxford Dictionary of Islam 2021). |

| West/Jews/Christians | The decision to put them together was made based on Zarqawi’s wording as was frequently encountered in the text. Together they form the “far enemy” as opposed to local rulers and Shias who constitute a “near enemy.” |

Out-groups (enemies) are coded if they come in the context of posing threat, otherwise they are NOT coded, for example, Zarqawi mentioning an Islamic scholar who replied to the former’s statement on the withdrawal of Italian troops. For an out-group to be coded as an enemy it must be implicitly or directly accused of posing a threat. Furthermore, attributing enmity to one group by way of associating it with another may be counted as two different nodes; an example of that is resembling Shias of Jews in the context of both being a threat.

Threats: realistic threats can be financial, political, physical, and threats to self-worth. While symbolic threats are those of religion and the groups’ morals and way of life. Such distinction is both necessary and useful in understanding how different types of threats are used. This, for instance, could prove especially important in the context of Counter Violent Extremism (CVE) where perceived symbolic threats may be remedied by psychological operations (psyops) or counter-propaganda wars. While perceived realistic threats may be remedied by revising military strategies or economic policies.

Looking for threats in the text means looking for threats that are directed towards the group as a collective, and are necessarily posed by another group. This group must be current and relevant; threats mentioned in way of lecturing religious sermons were not coded. If the people mentioned to have been killed are Jihadists, then the threat is coded if it’s in the context of drawing attention to an existing threats or conflict. Threats need to be external and posed by an out-group; i.e., mentions of threat as a result of people not following true Islam are NOT coded. Threats coming from god, whether a test or a punishment, are NOT coded.

Furthermore, threats must be current. However, out-groups in the latter might be coded as enemies if seen to make direct comparison to the current situation, for example, mentions of Shias betraying Islam in the past. Abstract mentions of threats in way of religious preaching are NOT coded. Past threats are coded only if they come in the context of the present threat, for example, Zarqawi using the past in order to invoke the threat Shias pose. On the other hand, realistic threats taking place as a result of jihadist operations are NOT coded. For example, Zarqawi talks about Muslims being killed in his operations.

Threats need to be external and posed by an out-group; i.e., mentions of threat as a result of people not following true Islam are NOT coded: threats coming from God, whether a test or a punishment, are NOT coded. Realistic threats taking place as a result of jihadist operations are NOT coded, for example, Zarqawi discussing Muslims being killed in his operations. Symbolic threats also need to be imposed by an out-group. For example, mentions of loss of morals, or a weakening of religious commitment that are happening with the development of time, as a result of globalization, or for any reason that is NOT caused by an out-group.

This article approach was to take coding in a parallel sampling process; such process allows for comparing two or more cases either to all other cases or to subgroups of said cases (

Onwuegbuzie and Leech 2015, p. 243). More specifically, this is a rather common approach called a “pairwise sampling process” where “all the selected cases are treated as a set and their ‘voice’ is compared to all other cases one at a time in order to understand better the underlying phenomenon and has been most common amongst qualitative sampling designs” (

Onwuegbuzie and Leech 2015, p. 243). In practice, nodes were not coded more than one time in a single page. Once a certain node was coded, it wasn’t coded again regardless of its repeated occurrence in the relevant page. This approach assumes that the presence of a node in a page is sufficient to consider that the node plays a considerable role in the page’s rhetoric. However, and most importantly, this approach meant that a percentage of how often a certain node is mentioned (relative to the number of pages) can be easily shown. The coding process itself adopted a rather conservative approach; the coded sentence, word, or phrase, should be directly and unequivocally referable to the nodes they are allocated to.

Furthermore, the context in which a judgment (i.e., the decision to code for a specific node) is only considered within the specific page. For example, when a word such as “enemy” occurs at the start of a page, it is only coded based on what accompanies it in the same page, despite already knowing who that enemy is (based on the previous page/s). This is to make the coding process more transparent, easier for revision and assessment, and replicable. If the word “enemy,” for example, was mentioned without a clear evidence (within the page itself) as to who the enemy in question is, the instance wouldn’t be coded at all.

4. Discourse Historical Genealogical Investigation of the Concept of Threat in Zarqawi’s Islamic Extremism

If our analysis showed a prominence of the concept of threat in Zarqawi’s rhetoric, we endeavor to outline the discursive-historical roots of such concept as adopted by Zarqawi. The importance of said approach is the evident link between creating agency on the one hand and creating emergency on the other: as Zarqawi attempted to speak on behalf of Sunni Arabs in Iraq and adopted the persona of a devout Muslim, he had to justify killing other Muslims in a manner that is compatible with, as well as convincing for, the targeted audience of Sunni Muslims.

Reisigl and Wodak saw the phenomenon of racism as a social practice and an ideology which is manifested discursively (

Reisigl and Wodak 2005). Similarly, the concept of

threat, and the phenomenon of discrimination associated with it, as used by Zarqawi, is also manifested discursively. And like racism, which must be put within its political, social, and historical contexts (

Reisigl and Wodak 2005),

threat ought to be analyzed discursively.

It is of the essence then, before analyzing the rhetoric of the man in question, that we understand the societal and cultural discourses that led, or at least aided, in adopting this specific rhetoric that we are later to shed light on.

Religion is perceived by billions of people in the world as a source of morality, something that is of intimate relationship with our subject; religion provides believers a framework, so to speak. John Locke, for example, viewed religion as a source of moral law, coming directly from the commandants of God (

West 2013, p. 474). The importance of Islam as a religion in this project comes clear as the man under study, and therefore his rhetoric, is fundamentally influenced by Islam; for him Islam is indeed a source of moral law. Furthermore, Islam’s influence here extends beyond mere theology; the history of Islam and its politics play a key role in shaping the world in which we live, and which, certainly, shaped the very identity of Zarqawi. The concepts of jihad, people of the book, and very importantly, the Sunni-Shia divide are integral concepts in this project. Of course, we are not the first nor the last to acknowledge the strong sectarian identification of many extremist organizations; the CIA’s 2007 National Intelligence Estimate, for instance, asserted that Al-Qaida works to include some Sunni communities in its efforts and from which to seek support (

Hoffman 2008, p. 134). Others showed that Lebanon’s Hezbollah enjoys large support in the country’s Shia community (

Norton 2007) as Shias in Lebanon are likely to support Hezbollah, its expansion, and its use of force (

Haddad 2006, p. 21).

In their attempt to understand jihadi rhetoric, some seek to find direct links between the use of the Quran and such rhetoric. Donald Holbrook, for instance, draws our attention to the employment, and alteration, of the Quran and the Hadith by jihadis for the purpose of the latter’s discourse; Holbrook, very helpfully, outlined how Ayman Al-Zwahiri relies often on verses from the Al-Mā’idah chapter of Quran which declares “O believers, do not hold Jews and Christians as your allies. They are allies of one another; and anyone who makes them his friends is surely one of them” (

Holbrook 2010, p. 16). Others complemented this addition to the literature by analyzing the tools which jihadis use in order to manipulate and shape certain religious texts into supporting these jihadis’ narratives: Ijtihad, for example, which is a “term in Islamic law that allows for the process of religious decision making by independent interpretations of the Quran and the Shariat” (

Venkatraman 2007, p. 236) was shown to have historically been useful in mobilizing Muslims against the Crusaders, something which jihadis later were inspired by, and made use of (

Venkatraman 2007, p. 236). Wiktorowicz found that jihadists expanded the concept of the apostates, from those who defect from Islam or reject essential teachings such as prayer, to leaders who refuse to implement Islamic law as jihadis see it; Wiktorowicz correctly forecasted that jihadis’ targets will include a wider range of categories, mainly Shias in Saudi Arabia, Pakistan, and in Iraq due to Zarqawi’s influence (

Wiktorowicz 2005, p. 94).

It is evident, then, that Islam plays a significant role in the discourse of jihadis worldwide, and that such role has, indeed, drawn attention from scholars who studied it from a wide variety of angles and methodologies. This article, therefore, will provide a fresh and deep analysis of this link between Islam, its history and theology, and jihadist rhetoric; fundamentally speaking, this research will make evident that, when it comes to said rhetoric, much of it comes down to the concept of threat and the utilization of that threat in that rhetoric. This utilization, in turn, needs the second key concept, which is out-group; whether a certain jihadist depends on the Quran, the Hadith, or Ijtihad, there are two essential ingredients: threat and out-group.

Jihad is considered, for the purposes of this article, Islam’s mechanism of collective self-defense and is traditionally seen as a collective duty, something that jihadis, including Bin Laden, sought to elevate to the ranks of individual duties; in fact, Bin Laden insisted that jihad be categorized as one of Islam’s five pillars and second to belief (

Gerges 2009, p. 3) This defensive and collective nature of jihad, according to the classical interpretation, is bound by strict rules and regulations, something that jihadists advocated to change, inspired by Sayyid Qutb, into an individual and permanent revolution against infidels (

Gerges 2009). Jihad, then, is done against the

out-group as defined by the jihadist implementing it; how

out-groups are defined and categorized by jihadists, and what the justifications are for waging war against them, lies at the heart of our project’s research question.

Out-groups in Islam constitute, naturally, non-Muslims who are perceived in relatively simple terms in Islamic theology. There are the infidels (kuffar) and there are Ahl-Alkitab, or people of the book, a Quranic term used to refer to Christians and Jews. The Quran was persistent in using the term Ahl-Alkitab to describe followers of the two other Ibrahimic religions, and when it comes to Christianity, it was more interested in showing the misconceptions and errors that Islam maintained Christians have about their own religion (

Griffith 2013). Islam’s relationship with Jews, on the other hand, was more troublesome; Prophet Muhammad had a series of treaties and wars with the Jews of Arabia. One notable incident was the attack against the Jews of Khaybar, which ended in the latter’s defeat and the capture of their leader (

Carimokan 2010, p. 401). In any case, the rule towards the people of the book was, generally speaking, that they are to be offered peace and tolerance as long as they pay their special taxes (Jizya) and abide by the few restrictions imposed upon them (

Long 2013, p. 283).

To consider Christians and Jews, for the purposes of this study, as out-groups is a relatively straight forward logical step. What is more difficult, and perhaps more interesting, is searching for the theological, discursive, and historical building blocks with which extremists like Zarqawi build their narrative for excluding other Muslims, and therefore, portraying them as part of the out-group and a source of threat. In this context, the concept of the Munafiq becomes very useful.

5. Converting the In-Group to the Out-Group: The Concept of the Munafiq

Between fragmentation and grievances exists a dialectic which we endeavor to uncover, the grievances, stimulated by certain policies or developments, are adopted, moulded, and reshaped by terrorists seeking further fragmentation. Such fragmentation, when intended to target a specific group, largely depends on the establishment of said group as an enemy (out-group) that, in turn, benefits from the portrayal of that group as a source of threat.

Drawing the lines of fragmentation, in the case of Zarqawi, required the exclusion of groups from the existing

in-group; Shias and Kurds were a prime example. Here we explore a rather important concept: the term

Munafiq lays the ground for such fragmentation by way of categorizing people accused of it as a source of

threat (therefore belonging to the

out-group) to Islam and Muslims. It is crucial, at this stage, to maintain that this concept is directly linked to that of “takfir;” the latter is the ultimate goal of the use of “

munafiq.” Takfir is “labeling other Muslims as kafir (non-believer) and infidels, and legitimizing violation against them” (

Kadivar 2020, p. 3). The term “

munafiq” is a theological-discursive tool for the purpose of takfir, as we shall see next. For more on “takfiri” ideology and its use in Islamic extremism see also (

Hartmann 2017;

Rajan 2015).

Munafiq (Plural Munafiqoon or Munafiqeen) is an Arabic word for “hypocrite,” a word that carries a rather heavy weight in Islamic theology. It is a “polemical term applied to Muslims who possess weak faith or who profess Islam while secretly working against it…the Quran equates hypocrisy with unbelief (kufr) and condemns hypocrites to hellfire for their failure to fully support the Muslim cause financially, bodily, and morally.” (

Esposito 2003). The evident importance of this term does not come as a surprise when we remember that the Quran has an entire chapter titled “al-Munāfiqūn” or “The Hypocrites”: The conceptual origin lies clear as the Quran defines hypocrites as those who “آمَنُوا ثُمَّ كَفَرُوا فَطُبِعَ عَلَىٰ قُلُوبِهِمْ فَهُمْ لَا يَفْقَهُونَ” “Believed then blasphemed thus their hearts are sealed and they cannot understand” (

Surah Al-Munafiqun n.d.). The concept of the Munafiq, then, leaves the door wide open for any who wish to demonize a certain group for one reason or another; it is an effectivediscursive tool which justifies a narrative of discrimination for individuals who are happy to employ such concepts for the purposes of solidifying their rhetoric, whether justifiably of not. Those portrayed as Munafiqs are beyond redemption and can never acquire God’s forgiveness: “سَوَاءٌ عَلَيْهِمْ أَسْتَغْفَرْتَ لَهُمْ أَمْ لَمْ تَسْتَغْفِرْ لَهُمْ لَنْ يَغْفِرَ اللَّهُ لَهُمْ إِنَّ اللَّهَ لَا يَهْدِي الْقَوْمَ الْفَاسِقِينَ” “It is all the same for them whether you ask forgiveness for them or do not ask forgiveness for them; never will Allah forgive them. Indeed, Allah does not guide the defiantly disobedient people.” (

Surah Al-Munafiqun n.d.).

This term acts as a conceptual framework for a discriminatory rhetoric weaponized against certain individuals or groups of people. Scholars have noted the significance of this term and its uses in different contexts and by different characters: Achmad Ubaedillah outlined how Abdullah Bin Abd Al-Razzaq, the Grand Shaykh of Khalawatiyah Samman in Maros, Indonesia, used the word Munafiq to describe those who denounce him, his followers, and his order; the word served as a double-edged weapon both to boost his religious authority, and to undermine his opponents (

Ubaedillah 2014). A well-known Chechen Mujahid against the Russian state, Dokka Umarov, also used the word Munafiq to describe his enemies, the word also was applied to those who doubted his ambitions of establishing an Islamic Commonwealth within the Russian Federation (

Knysh 2012, p. 316). In fact, Umarov categorized people into four distinct groups: Mujahideen, Kuffar (Infidels), Murtads (Apostates), and Munafiqs; Knysh noted the saliency of the word and how it was used to describe even observant Muslims, as long as they criticized Umarov or refused to join his fighters (

Knysh 2012, p. 323).

Zarqawi himself often utilized this word in his rhetoric, and for the same purposes: in a letter criticizing the Iraqi government and resembling it to that of Afghanistan’s Karazi’s, he combined

realistic threat and the term

Munafiq in accusing the Shia-dominated government of treason, stating that “History and contemporary experience prove that indirect colonization is the most potent weapon against this nation. Instead of the foreign infidel enslaving this nation and pillaging its resources, that, instead, will be done by

Munafiqs who belong to this nation in colour and tongue.”

2 The use of

Munafiq as a tool to demonize other Muslims is operated in parallel with associating them with the more traditional enemy (Christians or the West) and manifests itself in another example: Zarqawi urged his Mujahideen in another statement maintaining that

“فبِقتالكم حاملي لواء الصليب ومن سار تحت هذا اللواء من المنافقين والمرتدين من أبناء جلدتنا فإنكم لاتذودون عن حمى الرافدين فحسب؛ ولكنكم تدافعون عن الأمة بأسرها.”

“In your fight against carriers of the Cross flag, and those who marched under this flag of munafiqeen and apostates of our countrymen, you’re not just defending Mesopotamia alone, but you’re defending the entire nation.”

3

The concept of the Munafiq, then, opens the door to a flexible definition of the enemy and provides the framework for categorizing other Muslims as sources of threat. The Munafiq pretends to be a Muslim, works with the enemies of Islam, and seeks to destroy the creed of Islam and those who follow it. Fundamentally, the Munafiq is part of the out-group and therefore can be accused of being a source of threat. Every in-group requires an out-group, and if one is to portray certain groups as the enemy it is imperative that these groups are portrayed as out-groups first, before outlining their supposed threat. To accuse a specific group of hypocrisy may not, in itself, be a sufficient factor in the effort of creating an enemy of that group. This is accompanied and fortified by a threat-focused argumentation as we shall see in this article.

As an addition, and not substitution, historical contexts are integrated here as supporting evidence that shed light on the historical developments that shaped the rhetoric of the man under study; any rhetoric cannot be born in isolation of the times in which it was born. In fact, using non-discursive rhetoric is especially useful here, as it helps us better understand rhetoric when it is studied in multiple and layered texts such as the data we employ in this project. In essence, this is what Foucault would call the pre-discursive level of reality: “A discourse is defined in terms of statements (énoncés) of ‘things said. Statements are events of certain kinds once tied to a historical context and capable of repetition; the position in discourse is defined as a consequence of their functional use” (

Olssen 2014, p. 28).

In the next section we show the empirical application for the concepts discussed above, which are, later, linked to the real-world events. The relevance of these concepts is shown over a considerable amount of data, as well as the dialectical relationship therebetween those events and the rhetoric itself.

6. The Big Picture: The Totality of Zarqawi’s Discourse on Out-Groups and Their Threat

6.1. Out-Groups

Our analysis of the different

out-groups manifested in Zarqawi’s rhetoric showed a clear categorization of four different groups of enemies portrayed: Shias (or Rawafid according to Zarqawi), the West with which Christians and Jews are merged, local ruling regimes, and Kurds.

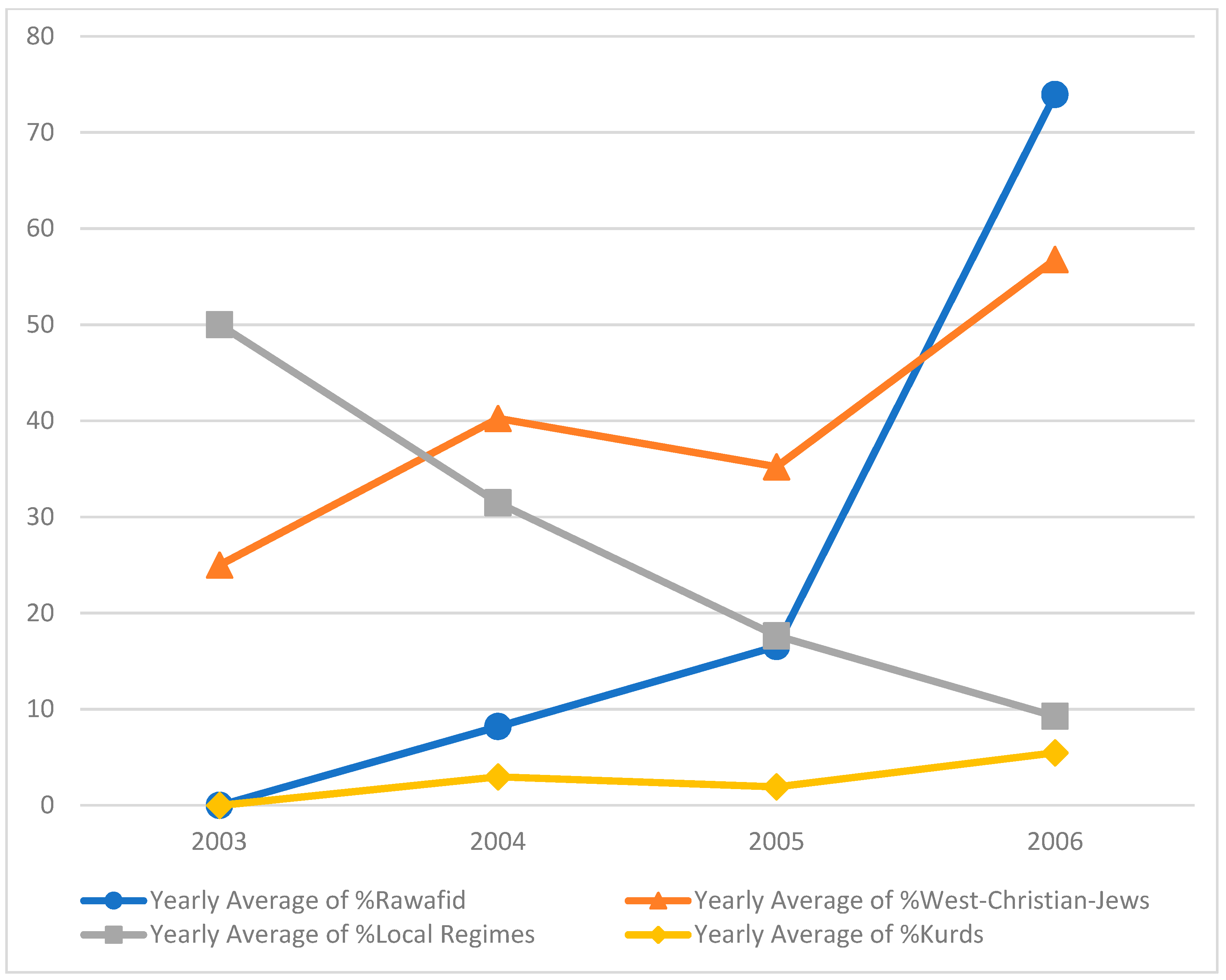

Figure 3 shows the occurrence rate of each node through time and in each individual statement, while

Figure 4 shows these rates relative to the average percentage of yearly occurrences. The charts resulting from our analysis paint an interesting picture of Zarqawi’s priorities when it comes to whom he identified as enemies. In said picture, two categories of enemies appear as most salient: the West-Christians/Jews and the Shias. What is especially noticeable is the evolution of the Shia node through the coding process. Shias appear to evermore gain a greater role as Zarqawi’s enemies through time. Starting from 2005 they begin gaining prominence, with the W-C-J category leading the charts, before becoming the unquestionable centre of focus in 2006.

Overall, the analysis shows a prominent role of out-groups in the formation of Zarqawi’s discriminatory rhetoric; they were featured in every statement, and in a few they took a substantial share of these statements. An example of which is a document titled “الحق بالقافلة” or “join the caravan,” in which W-C-J nodes were present in 9 out of 11 pages, and local regimes were mentioned in 6 pages. Our charts demonstrate the relevance of out-groups in our database; while the W-C-J category is ever prominent, we find a clear sharp rise in the prominence of the Rawafid (Shias) category.

6.2. Threats

In June 2006, a report produced at the Combating Terrorism Centre at West Point Academy highlighted an analysis in which Zarqawi’s then newly released statement was the focus. The author stipulated that “Although attacks continued as Zarqawi lowered his profile, his reduced media presence left them disassociated from a larger strategic purpose. This statement is intended to rectify that situation by clearly explaining the ‘apostasy’ and danger posed by the Shi’a.” (

Fishman 2006, p. 1). This report referred to one of the statements under study in this project and reflected a parallel with our research goals. Indeed, linking

out-groups to

threats was a strategic decision made by Zarqawi, a strategy that we, here, uncover.

For example, a 2004 statement titled “

رسالة الى الأمة” or “letter to the nation”, was constituted in 13 pages, 12 of which mentioned

realistic threats, and 8 mentioned

symbolic threats. A 2005 statement titled “

أينقص الدين وأنا حي” or “would the religion be harmed while I’m alive” was spread over 34 pages, 24 mentioned

realistic threats and 13 mentioned

symbolic threats.

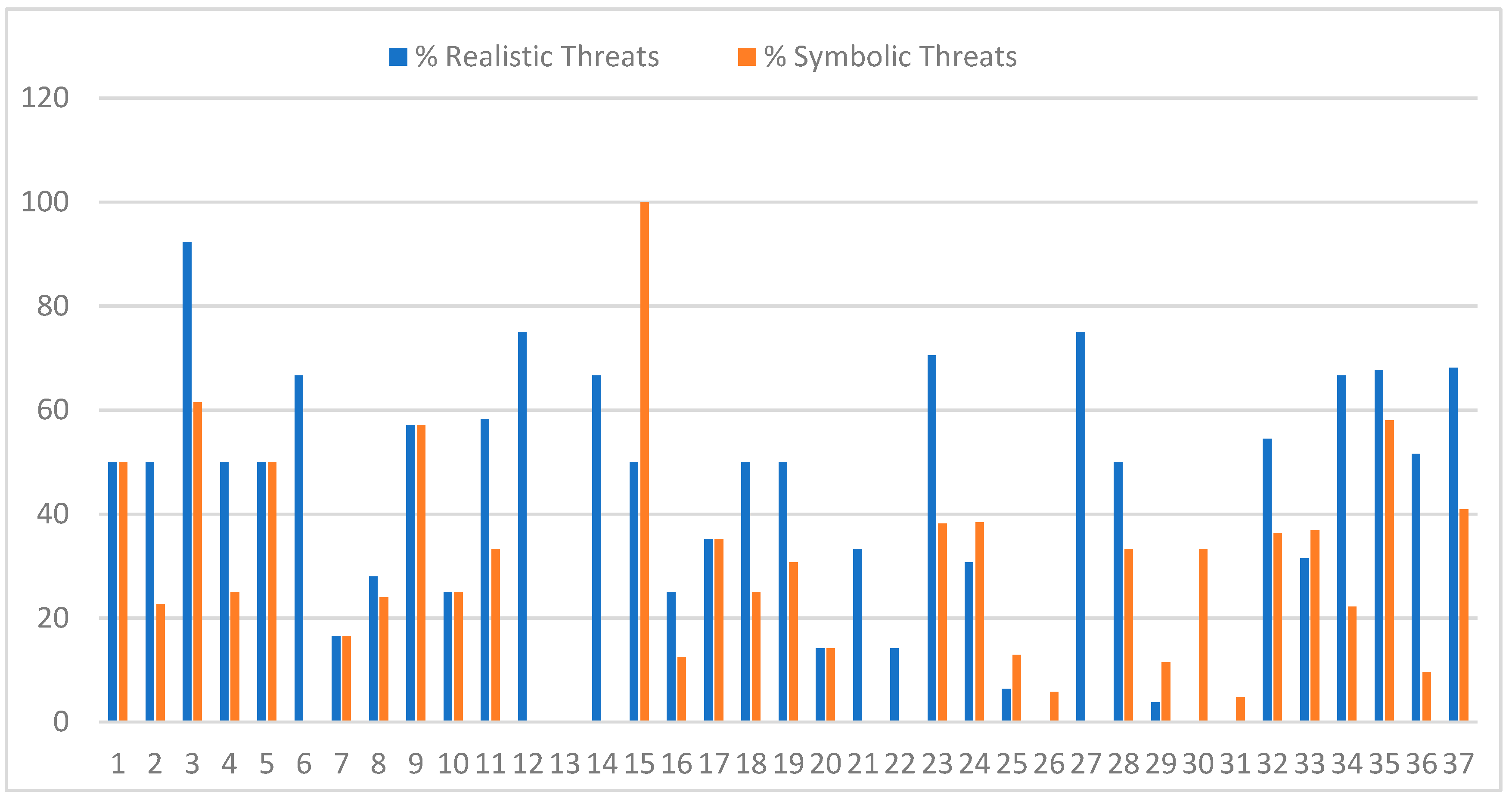

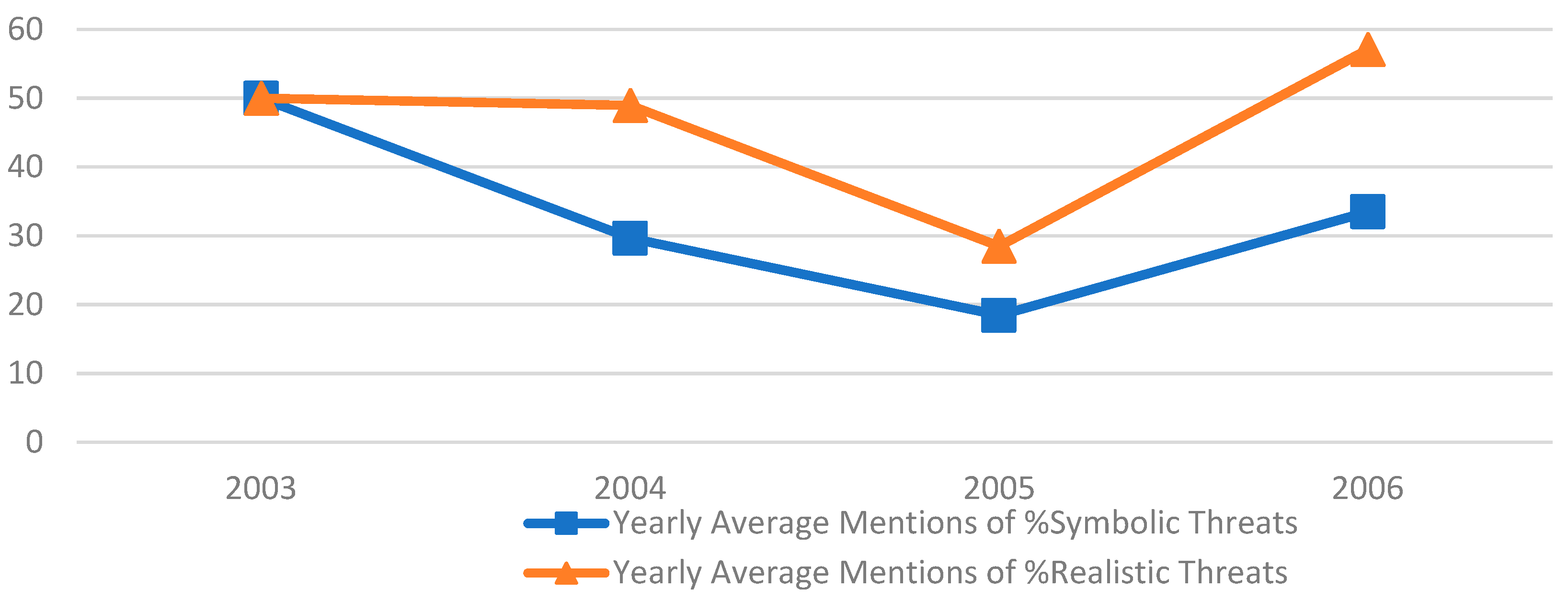

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 show the saliency of

realistic and

symbolic threats: in both we encounter the importance of

threat as a building stone upon which Zarqawi’s rhetoric was established.

Both realistic and symbolic threats were consistently present throughout the data, although realistic threats seem to be slightly more dominant. This, interestingly, shows the limitations of dependence on discourse per se: The religious order upon which Zarqawi built his legitimacy was of evident value in these texts. However, the reliance on symbolic threats was clearly far from sufficient for Zarqawi; realistic threats were shown to be more salient in the vast majority of statements analyzed. This highlights the direct relationship between developments in the political sphere and the rhetoric of a terrorist leader willing to use these developments by way of lyrical weaponization.

Now that we have established the various ways Zarqawi’s rhetoric was engaged with, as well as affected by, historical developments in post-war Iraq, we discuss next the particularities of this dialectic in a time-specific manner. Linking our findings to these developments shall shed light on the mechanisms by which said developments fortify, if perhaps inadvertently, terrorist rhetoric and, therefore, fuel violent conflict through further inflammation of grievances and fragmentation.

7. Discussion: The Vicious Circle: How Allies’ Policies Emboldened Sectarian Violence

As mentioned in the introduction, post-war Iraq witnessed a staggering rise of terrorist attacks, particularly in the years prior to the death of Zarqawi. Our investigation so far has shown the mechanism by which Zarqawi incorporated various out-groups in his rhetoric. Next, we outline the dynamics in which Zarqawi’s rhetoric reflected, as well as benefited from, the developments, resulting in a pronounced interrelationship between developments on the ground (i.e., factionalism and Sunni grievances), Zarqawi’s rhetoric, and terrorist related deaths. Our research shows a clear correlation between the developments on the Iraqi land and Zarqawi’s formatting of the out-group (enemy). At the early stages of the occupation the rhetoric was evidently keen on defining the far enemy (W-C-J). That, however, began to change by the year 2005; such change can be better understood by linking the historical events on the ground with the rhetoric as analyzed. Such linkage may also demonstrate how hasty policy making can deliver monumental damage to the fabric of society and, therefore, open the door for terrorists such as Zarqawi to capitalize on the societal void and the chaos resulting thereof.

In May 2003, the U.S. government appointed Paul Bremer, which effectively made him the ruler of Iraq, in his capacity as head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, who, in turn, appointed 25 Iraqis as members of the Iraqi Governing Council (

Katzman 2009). The CPA’s carried a process of “de-Baathification” of the country and rejected the return of armed forces members to service; such measures were taken to assure Shias and Kurds of the democratic process (

Katzman 2009). At such an early stage, as we see, sectarian and ethnic considerations were given absolute priority for a country trying to recover from war and chaos; the roots of societal divisions in Iraq were re-planted and replenished.

Zarqawi’s statements often kept with the political developments on the ground and provided commentary on them; they constitute a rather useful tool for tracking how these developments influenced, as well as were used by his rhetoric. For 2003 we only have one statement which, naturally, focused on the external threat posed by the far enemy. In fact, we see in our analysis that Zarqawi focused on the W-C-J and the local regime (the Jordanian King), which worked with the allies.

By the year 2004, the Shia-dominated Iraqi government had started to fight the insurgency together with the allied forces. Zarqawi was already making himself infamous as Iraq’s most wanted man. Newsweek magazine described him as “The World’s Most Dangerous Terrorist” after U.S. officials accused him of personally beheading Nicholas Berg, an American hostage (

Michael and Hosenball 2007). Zarqawi indeed issued a statement following the murder of Berg in which, our analysis shows, he blamed the W-C-J, citing, amongst others, the torture stories leaked from Abu Ghraib prison: “As for you, mothers and wives of American soldiers… we tell you that the honour of Muslims in Abu Ghraib prison is defended with blood and souls” a clear reference to a

symbolic threat.

4Indeed, the years following the Iraq War witnessed an evident dominance of Shias over the Iraqi government, its army, and its security forces. Case in point was that of Interior Minister Baqir Jabr al-Zubeidi: a former high-ranking commander of the Shia Badr Organization who was accused by Sunni Arab notables of turning a blind eye to the torture, kidnapping, and murder of Sunnis in the country, all crimes committed by the Iraqi Security Forces, which were dominated by Shia militias (

Beehner 2006). Such Shia militias were fighting the Sunni-led insurgency alongside the U.S. forces, despite the former’s role in the worsening sectarian tensions. These militias were officially banned, but the U.S. Defense Department continued to encourage them and were seen as an Iraqi problem rather than an American one (

Beehner 2006). Zarqawi, consequently, made sure to tackle the topic of the Badr Organization’s activities: “Everybody knows the truth about the demonic alliance… First, Americans, the carriers of the crucifix banner, Second, Kurds in the form of Peshmerga forces… Third, Rawafid, the enemies of the Sunni people represented by the Badr Brigade.”

5 By that time, our analysis shows, Shias had started to be ever more mentioned in Zarqawi’s rhetoric.

Sunni Arabs were left in a hostile environment in which even the government is an oppressor. Such developments left Zarqawi great opportunities on which he could capitalize. By 2005, Shias, as our chart shows, became a constant target in the man’s rhetoric; this correlated with a major transition of power from the allies to Shias by way of elections in which Shias won the vast majority while Sunnis boycotted; the latter were not helped by Zarqawi’s threats against the democratic process and those who took part in it (

Gonzales et al. 2007). In fact, Zarqawi had started demonising Shias in 2004, if on fewer instances: in a statement in October 2004, he commented on the battle of Fallujah “It’s you I address, my nation, as your sons’ blood is spilled in Iraq all over, and in Fallujah especially, after the worshippers of the crucifix and those with them of our skin, who… betrayed God and his Prophet, such as the Peshmerga, and Rawafid.”

6 Here he clearly chose to refer to

realistic threat.

Zarqawi, then, was able to frame a narrative of

realistic and

symbolic threats, to which he linked the various factions of Iraqi society that he wanted demonized and outcasted, further adding fuel to the fire of the civil war and reverse engineering the allies’ and Iraqi government’s narratives of fighting extremism. Legitimate existing grievances were aligned with a discriminatory rhetoric, giving the former a weight of legitimacy and authority. This pattern became far more prominent by the year 2005. For example, in the first statement of that year, Zarqawi addressed the then on-going Fallujah battle, portraying an infidel army seeking the harm of Muslims. He stated that “The battle uncovered the ugly face of Rawafid… they had a large role in the enactment of killing, robbery, vandalism, and the murder of unarmed children, women, and elderly… and for the record, 90% of the profane army is from Rawafid and 10% are of Kurdish Peshmerga.”

7 The employment of

realistic threat here relied on a straight-forward accusation: Shias and Kurds are murdering our innocent civilians.

A Shia-dominated government, and the associated Sunni complaints thereabout, constituted rhetorical fuel for Zarqawi, which nurtured the latter’s discourse against Shias and Kurds. The end of 2005 witnessed parliamentary elections that resulted in an overwhelming win for the Shia-led United Iraqi Alliance, followed by the Sunni Arab Iraqi Accord Front, which won 58% and 18.6% of the votes, respectively (

BBC 2005). These elections, this time, enjoyed a large Sunni Arab presence but suffered a crisis of its own; the Iraqi Front Accord rejected the results and complained the elections had been rigged; the secretary general of the Iraqi Islamic Party was quoted as warning the electoral commission “not to play with fire” (

BBC 2005). That again, reflects the relevance of these developments in shaping and helping Zarqawi’s rhetoric. In a statement issued a few months later, he reminded his audience that “the follower of the political map of Iraq knows that the majority of parliamentary seats are occupied by Shias, and Kurdish and Sunni secularists…and this tells us that parliaments will always be ruled by tyrants.”

8 In contrast to the last quote above where

realistic threat was mentioned, it is employed in a less direct way, and comes with a warning against democracy: the

out-groups are denying us political power through democracy.

In fact, Zarqawi’s focus on the Shia had only intensified by 2006, during which the very last three statements featured in our analysis were solely addressed to the portrayed danger of Shias. These documents were in three parts and titled “Have you received the talk of Rawafid.” Quantitatively, our analysis shows this focus as paramount, with the first document mentioning Shias as an enemy in around 80% of all pages, the second document 96%, and the third statement at 100%. This later emphasis on Shias as a predominant enemy is well demonstrated in

Figure 4.

The justification, which comes at the end of the third part linked by a long historical lesson on Shias’ past infractions against Islam (

symbolic threat) and Sunnis (

realistic threat), is eventually associated with claimed breaches of the Iraqi government and its associated organizations. Zarqawi maintained that “if we consider… the reality of Shias in Iraq today, we find that the Badr Brigade and the Mahdi Army…raid Sunnis’ homes with the pretense of looking for jihadists…they kill the men, imprison women and harass them… these tragedies are committed by Shia militias alone, or with the help of occupying American forces”

9 and follows by calling Sunnis to arms “Sunni people wake up and rise, and be prepared to get rid of Shia snakes’ poison.”

10Having established Shias’

realistic threat, Zarqawi complements his arguments by establishing

symbolic threat. At this stage, there exists a remark that supports our quantitative findings highlighting the prominence of Shias as the main enemy: Zarqawi maintained that “They committed a hideous act…by committing blasphemous deeds

which exceeded those of the deeds of this religion’s original enemies, as they tore Qurans apart as well as dozens of important mosques until they proved that they are, indeed, God’s enemies.”

11 Here Zarqawi clearly distinguishes Shias from the far enemy (

W-C-J) and puts them in the position of Sunnis’ largest enemy before all others. Their

threat is

symbolic, yet grievous, clearly by their indication as Islam’s biggest enemy. Zarqawi concluded this last statement, issued a few months before his death, calling Shias, namely one spiritual leader of theirs, Muqtada al-Sadr, to war: “Based on what has been said so far, we have accepted to join the battle against you and your flock of sheep.”

12 8. Conclusions

Iraq, following the invasion of 2003, plunged into a vicious circle of sectarian violence, the aftermath of which is still felt to this day. Within those years the first three were of particular importance as they set the tone for the country’s political environment. An overarching sectarian war took hold; one of its key players was Abu Musa’ab Al-Zarqawi.

In this article we sought to shed light on the dialectical relationship between reality and rhetoric, that is to say, on the effects of grievances and fragmentation in aiding terrorist rhetoric. We showed how Zarqawi took advantage of an existing fragmented environment, which was charged with sectarianism and racism, in order to fortify a rhetoric of exclusion and violence. We also showed how the Sunni Arab community’s grievances constituted fuel, for Zarqawi, for the purposes of cementing said fragmentation.

With the help of Social Identity Theory and Integrated Threat Theory, we analyzed thirty-seven statements by Zarqawi that permeated his active insurgency in Iraq between 2003 and 2006. In this analysis, we demonstrated the relevance of these two theories in studying the rhetoric of violent extremism: the value of the concept of the out-group was evident in the form of taking advantage of existing fragmentations to create a narrative of “us vs. them,” while the concept of threat was weaponized in the context of existing grievances.

Furthermore, in Zarqawi’s process of creating agency and emergency, we found that the occupation forces and its allied Shia-dominated government committed mistakes, as well as transgressions, against Arab Sunni communities, which were quickly and concretely taken advantage of by Zarqawi. Through careful analysis of Zarqawi’s statements, we tracked the development of his narrative through time and linked the fulcrum of his rhetoric, wholly as well as within individual statements, to developments which happened on the ground.

A sectarian-based political system only aggravated the existing fragmentations in an already unstable country, while an increasingly Shia-dominated political regime aggravated grievances within the Sunni Arab community. As Shia domination over the political scene, as well as over the security forces, became obvious, Shias gradually became Zarqawi’s main target as his rhetoric portrayed them as the most salient of dangers. All this indeed, correlated with one of the country’s bloodiest years, and which at the same time, saw the world’s highest number of terrorism-related deaths.

This article outlined the fact that terrorism doesn’t take place in isolation of its environment; government actions and policies were proven to provide a fertile ground in which terrorism prospers and upon which terrorist rhetoric can be built. The allies’ transgressions in Abu Ghraib prison and the Iraqi government’s tolerance, if not adoption, of Shia militias such as the Badr Brigade, we proved, were invaluable rhetorical capital for Zarqawi to launch his attacks on the status quo and to call for the murder of Westerners and Iraqis alike. Counterterrorism efforts, subsequently, ought to consider the internal policies and living environments under which communities under threat of radicalization live.

It ought to be clear, by now, the critical importance of paying attention to societal fragmentation and grievances, especially in unstable regions. Zarqawi’s case represents a valuable case study of the detrimental consequences of these factors on the security and stability of society. We have seen how historical grievances can pose as open wounds ready for malicious actors to infect and develop into horrific existential threats. This case study is a lesson for policy makers in the crucial significance of carefully studying the history of the communities that they aim to govern and lead; it is a reminder that the present never lives in isolation, that the past matters, and that ignoring the latter may mean that someone else can open the forgotten pages of history and edit them for his own malicious purposes, as Zarqawi did.

The aftermath of Zarqawi’s death, leading to the meteoric rise, as well as fall, of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, is a clear indication that Zarqawi’s case example is one which is always prone to be reproducible, unless the underlying grievances are tackled and treated, probably by way of true democratic institutions and rule of law. Iraq’s example shows how ignoring painful history may very well lead to its recurrence.