Abstract

The many changes that occur in the lives of older people put them at an increased risk of being socially isolated and lonely. Intergenerational programs for older adults and young children can potentially address this shortfall, because of the perceived benefit from generations interacting. This study explores whether there is an appetite in the community for intergenerational programs for community dwelling older adults. An online survey was distributed via social media, research team networks, and snowballing recruitment with access provided via QR code or hyperlink. Semi-structured interviews were undertaken with potential participants of a pilot intergenerational program planned for the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, Australia in 2020. The interviews were thematically analyzed. Over 250 people completed the survey, and 21 interviews took place with older adults (10) and parents of young children (11). The data showed that participants were all in favor of intergenerational programs, but there were different perceptions about who benefits most and how. The study highlighted considerations to be addressed in the development of effective and sustainable intergenerational programs. For example, accessing people in the community who are most socially isolated and lonely was identified as a primary challenge. More evidence-based research is needed to support involvement of different cohorts, such as those who are frail, or living with physical or cognitive limitations.

1. Introduction

The global ageing of the population means older adults are a more visible part of the community than ever before. As a result the needs and wants of older people are coming into sharp focus, in places like Australia where commissioned reports are revealing a shortfall between care needs and services available (; ; ; ; ). Not only clinical and medical needs of older people are to be addressed, but also their psychosocial wellbeing and quality of life (). There is a growing recognition that older people have a greater risk of feeling socially isolated and lonely, to the extent it negatively impacts health and wellbeing (). Research has linked social isolation and loneliness to physical symptoms such as high blood pressure, heart disease, lack of mobility, and to anxiety and depression (). However, identifying people at risk is complex, social isolation and loneliness are not the same thing. Not having contact with others can lead to social isolation, but, living or spending time alone may be a personal choice, not giving rise to loneliness. Loneliness may occur through lack of social support and social isolation, but may also be felt by people who are not socially isolated, for example, in aged care homes (; ). Loneliness, then, is a psychological condition when “… the individual perceives a discrepancy between two factors, the desired and achieved pattern of social relations” (). Less opportunities to socially engage, fewer quality relationships, and a reduction in extended family being in close contact, are often identified as contributing to both social isolation and loneliness in older adults. For older adults, and children often growing up without grandparents in close proximity, there are fewer opportunities for casual intergenerational engagement (). This can result in the stereotyping of older and younger people and lack of understanding across generations, compounding both social isolation and a sense of loneliness (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

Increasingly, ways to support active ageing, quality of life, and the wellbeing of older adults in the community and stave off the need for clinical or medical interventions are being explored. Programs that connect people and provide activities for older people have been shown to contribute to ageing well and physical and mental health (; ; ). Amongst these, intergenerational programs that bring together older adults and young children have become more popular, to address the shortfall in intergenerational engagement and the perceived benefits from older people and young children interacting. They present opportunities for social connection and cooperation to overcome social isolation and loneliness, promote mobility, and challenge the stereotyping of generations that can lead to lack of confidence and reduced esteem (; ; ; ). They have also shown to promote physical activity, social interaction, cognitive engagement, and contribute to older adults’ self-worth (; ). There is a growing interest in intergenerational programs from positive representations in popular television shows such as Old Peoples Home for 4 Year Olds, both in the UK and Australia (, ; , ) They show the potential benefit in bringing together pre-school children, whose time is not yet absorbed in a school curriculum, with older adults, who mostly live in the community.

Theoretical frameworks are beginning to emerge to support the development of intergenerational programs and support claims for their efficacy, and to develop and investigate the impact of intergenerational practices. For example, contact theory suggests that simply bringing together the young and elderly in interactive contexts can overcome generational stereotyping, an important aim for many intergenerational programs (; ; ; ; ; ; ; ). However, existing research also shows the limitations of simply putting different generations together in an unstructured way, suggesting the most effective way to build relationships and counteract stereotyping in intergenerational practice is through shared purpose, activities, and focus (; ; ; ; ). Thus, the perceived benefits of intergenerational programs for older adults is when they provide purposeful and structured opportunities to engage with children in enjoyable, socially appropriate activities (). However, intergenerational programs, and the reporting of them vary greatly on what types of activities have most impact. While some discuss the use of single-focused activities, such as singing, technology, or art, reporting of other programs barely mention the types of activities undertaken (; ; ).

Another theoretical framework explored has been that of life course development with a focus on educational opportunities for children’s development, and personhood (). Intergenerational programs have shown that engagements were highly productive when older adults take on a ‘scaffolding’ role with children. However, for the most part, this occurred with older children and pre-teens, and relatively few programs have engaged with pre-school children (; ). However, children exposed to intergenerational programs have been shown to have higher levels of social acceptance, less social distance, a greater willingness to help, greater empathy, slightly more positive attitudes towards older people, and be better able to self-regulate their behavior (; ). Moreover, such programs can build social capital, for children, by raising their awareness of others and exposing them to new attitudes and behaviors, in their having friends in different age groups, and in recognizing themselves as part of a larger community (; ).

Some intergenerational programs found that assigning roles was important for participants, such as being pseudo grandparents. However, while these substitution roles may be accepted and welcomed by older adults, they can also potentially limit exploration of what intergenerational relationships can be, both within the program and more broadly across society. (; ; ). Importantly existing intergenerational practice research showed a need for reciprocity, flexibility, and “give-and-take” between different age groups, productive meaningful joint activities, and sharing experiences that are not just role-play or learning but about celebrating together. (; ; ). Intergenerational programs present opportunities for friendly informal encounters that counter “… a world that appears to put increasing value on expertise and specialist knowledge over traditional forms of knowledge or wisdom …” recognizing that “the process of becoming a more integrated human being requires knowledge that is created by all generations” ().

Many intergenerational programs focus on older adults in aged care facilities and community care centers, likely to have reduced independence and autonomy, who would seemingly benefit from intergenerational programs. In terms of research, this provides relatively straightforward access to study participants in pre-formed groups (; ). However, accessing community dwelling elderly who are socially isolated and may benefit most has been identified as difficult. Older adults volunteering for intergenerational programs show self-motivation often lacking in people identified as socially isolated, lonely, or depressed—who are less likely to come forward (). Even those motivated to engage can lack confidence and fear that children may simply just not like them (). Therefore, there is a risk that it is the most active and motivated that engage with these programs, and thus more work is needed to reach those less likely to come forward (; ).

Despite the growth in interest and increased theorizing of intergenerational programs there remains a paucity of published data available on the feasibility and efficacy of community based intergenerational programs, how and why they are beneficial, and what leads to successful engagements for all involved (). Before we can further explore the potential efficacy of community-based intergenerational programs we need to understand whether these are of value to the community and how they are perceived. Our aim was to gain an understanding of community perspectives on community-based intergenerational practice using a combination of an online survey and interviews to scope perceived benefits and risks and assess the level of interest.

2. Materials and Methods

Data were collected concurrently in two ways, an anonymized online survey and a series of semi-structured interviews, conducted by the lead author. Through two studies we investigated a perspective not fully explored elsewhere. The survey was aimed at a broad population not limited by geographical location, age, family role or circumstances. The interviewees were older community dwelling adults or parents of preschool children living in close geographical proximity to a planned community pilot intergenerational program. They were not expected to have prior experience or knowledge of intergenerational programs, but they could potentially take part in a one. We wanted to gain insights into preconceptions about intergenerational programs, willingness to take part, reasons for or against, and expectations and concerns. An important aspect of the interview study was to find about who the older adults were and about their lives and experiences—which has not been fully explored in existing studies, or the data have simply not been reported. However, understanding who may be in the room for intergenerational programs provides insights on how to cater to their needs and produce the best outcomes (). Ethical approval was granted by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel C Behavioral Sciences HC 3351 for an online survey, and HC 3368 for semi-structured interviews.

2.1. Study 1: Online Survey

The online survey was co-developed and piloted with community representatives including parents, older adults, and staff working for organizations delivering community-based aged care and pre-school education. Data were collected in an anonymized form using online survey software (Qualtrics, Provo, UT, USA) () with questions asking about attitudes to social activity, social engagement, and intergenerational programs. Chi-squared test was used to compare the proportions of participants between respondent groups who chose a specific answer to each question. A p-value of <0.05 indicated differences in the proportions between respondent groups. The survey was publicized using a combination of printed paper and online advertisements and distributed via social media, research team networks, recruitment via snowballing. Access to the survey was via a QR code or hyperlink.

2.2. Study 2: Semi-Structured Interviews with Community Members

A series of semi-structured interviews were undertaken with potential participants of a pilot intergenerational program planned for the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, Australia at the beginning of 2020. The interviewees were parents of young children attending a Christian pre-school connected to a church and older community dwelling adults living in the local community. The pilot project aimed to explore the feasibility of setting up intergenerational programs in the community, to test the appetite for such programs amongst older adults and parents of pre-school children, to explore the logistics of such a program, and establish the research criteria for a randomized control trial (RCT). However, due to a nation-wide COVID-19 pandemic lockdown (first wave) in Australia, the community-based intergenerational program was postponed until March 2021. While the pilot project was delayed interviews were carried out by phone and online as they could provide valuable insights about community preconceptions of intergenerational programs.

The rationale for semi-structured interviews was “the researcher determines the structure of the interview and agenda through the questions asked. The participant controls the amount of information provided in responses … has the control over the pacing of the interview, what will be disclosed (the amount of detail, scope of the interview, etc.), and the emotional intensity”. Furthermore, while “initially the researcher may control the direction, this shifts as the participant becomes more comfortable with the interview and commences narration” (). The semi-structured interviews encouraged participants to be open about their thoughts and feelings and enabled them to introduce topics and issues important to them.

Interview participants were invited to talk about their knowledge of intergenerational programs, what they thought were the benefits for older adults and for children and their families, and what would be the challenges. They were also asked about the types of activities they thought would be most appropriate or suitable. They were invited to comment on how older adults and pre-school children should be introduced to each other at the start of the program and say goodbye at the end. Participants were asked about the ideal logistics for these types of programs, such as, duration, frequency, and preferred location. They were invited to provide details about their background, life experiences, family situation, and to comment on any other aspect of the project of interest or concern to them. The interviews took place during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in Sydney, Australia where participants had been subjected to a three-week lockdown, being allowed outside only for vital shopping, medical or care needs, and for exercise. As this potentially had implications on social isolation and loneliness, participants were asked about their experience of the lockdown. COVID-19 restrictions meant the interviews had to be conducted by phone or zoom1 rather than face to face, as originally planned (see Appendix A Figure A1).

2.2.1. Participants

Older adult participants were recruited from a callout made by the Christian church connected to the pre-school participating in the pilot project. People who identified as older adults were invited to take part in the interviews about intergenerational programs and could nominate themselves to be part of the pilot program, although this was not a requirement for the interview. Information and leaflets were distributed throughout the parish and local community. Parents of children attending the preschool were invited to contact the pre-school about their child taking part in the program and were given a researcher’s contact details if they agreed to be interviewed.

2.2.2. Analysis

The interviews were audio recorded and subject to thematic analysis (; ). The audio recordings were uploaded to a widely used server-based application2. Automated transcriptions were produced and downloaded as text documents. As expected, the accuracy rate of the auto-transcripts varied significantly depending on people’s accents, tone of voice, volume, and quality of the recording. However, this was not of concern as the transcripts were used primarily to organize the coding and retain the timeline of the conversations. Coding was carried out directly from the audio recording onto auto transcripts imported into NVivo for Mac (). The researcher engaged with each recording on multiple occasions. Coding directly from audio recordings allows the researcher to hear the tone, emphasis, and emotion of the speaker. The data was divided into two ‘cases’—older adults and parents—to allow for issues to be tracked and for cross referencing. Inductive coding was carried out directly from the audio by creating nodes (or selecting existing nodes already created from the data)3 and marking the auto transcript at the appropriate timeslot. This ensured that the researcher was able to locate the data relating to the node quickly and provided access to participants’ spoken words.

Fine detailed coding of the data was carried out by the first author, an experienced reflexive qualitative researcher (; ) using an iterative six-phase process as identified by () (i.e., become familiar with the data, generate initial codes, search for themes, review themes, define themes, write up (). In addition, the data was examined for semantic level surface meaning of what has been said, and latent level, i.e., what is meant. This triangulation of qualitative data allows for the researcher’s reflexivity to be a resource and not ‘noise’ to be minimized and allows for this explorative study to engage with potentially deviant data as well as consensus ().

The first phase of coding was inductive and focused on half of the audio recordings and auto transcripts—five older adults’ and five parents’ interviews. Nodes consisting of keywords or phrases were created from each recorded interview. Coding was undertaken initially at a fine detail level. For example, names of careers and jobs were coded as part of the participants background data, (teacher, journalist) types of activities people would want the program to engage with (reading, drawing), and health related matters (mobility, heart problems, cancer). More than 1200 coding nodes/topics were created (Table 1). The coding nodes were analyzed for duplications and grouped to create categories when relationships between nodes were identified. For example, journalist, scientist, and retail-worker were combined under the category of ‘career’ and patience and kindness under ‘traits’. The 1241 nodes, relating to 2500 references, were grouped into 46 categories. The second coding phase was completed more quickly, using existing nodes, as repetition of topics occurred, while remaining open to new topics. After coding all nodes were checked for duplication and subject to further categorization before analysis (Table 1).

Table 1.

Survey demographics.

3. Results

3.1. Study 1: Online Survey

A total of 258 adults completed the online survey. Respondents were divided into four groups: ‘Older Adults’ aged 60+ years (n = 46), ‘Parents’ under the age of 60 years who were a parent or guardian of children aged 3–5 years old (n = 49), ‘Carers’ (n = 75) including 10 early childhood educators and 65 aged care providers or relatives or carers of older adults, and ‘Other’ (n = 73) who did not identify as being an older adult, parent, or carer of children or old adults. The majority of respondents in each group were female (82.6%, 93.9%, 89.3%, and 87.7%, respectively) with the majority living in a major city (73.9%, 72.3%, 81.3%, and 87.5%).

Of the Other group, 9 (12.3%) were in the 20–29 age group, 20 (27.4%) in the 30–39 age group, 25 (34.3%) in the 40–49 age group, and 19 (26%) in the 50–59 age group. There were 64 (87.7%) females, 8 (11%) males, and 1 participant who chose ‘prefer not to say’ for gender. Most lived in New South Wales and the majority lived in a major city (n = 58, 80.6% and n = 63, 87.5%, respectively) (see Table 1).

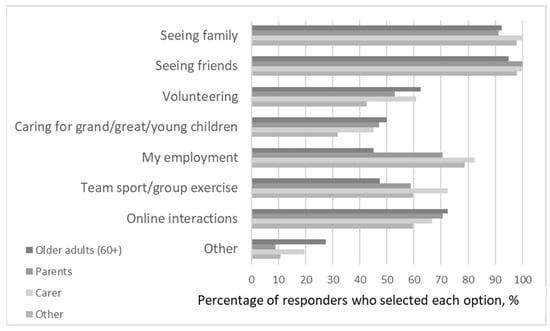

3.1.1. The Attitudes to Social Activity and Social Engagement

Generally, participants reported experiencing social activity and social engagement positively, with 89 percent stating it helped them feel connected and supported, and was good for their health and wellbeing (85%). Some also reported that it could be a negative experience, with almost a third of Older Adults (30%), and over half the Parents (59%), Carers (59%), and Other (51%) groups indicating that social activity and social engagement could sometimes be a chore (p = 0.01). Similarly, 10% of Older Adults. 35% of Parents (35%), 27% of Carers, and 19% of Other felt that social activity and social engagement could be distressing (p = 0.05). Out of the eight statements presented to describe meaningful social engagement in Figure 1, seeing family and seeing friends was the most commonly selected, chosen by at least 91% of participants. The proportion of participants who associated volunteering, caring for children, team sport or group exercise, and online interactions with meaningful social engagement ranged from 40% to 70%, with each statement viewed similarly by all four groups. However, fewer Older Adults (45%), viewed employment as a form of meaningful social engagement than Parents (71%), Carers (82%), and Other (79%), (p = 0.0006).

Figure 1.

How participants categorized meaningful engagement.

3.1.2. Most Participants Supported the Idea of Intergenerational Programs

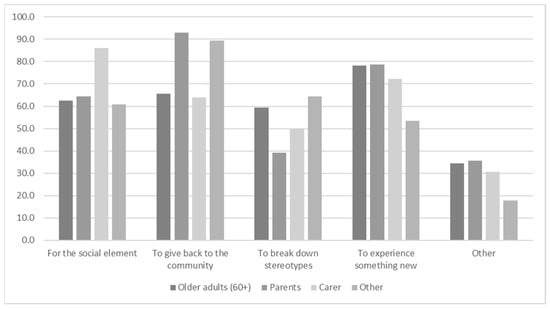

More than 92% in each group felt that intergernational programs have the potential to increase understanding and friendships across generations, provide unique learning opportunities and improve communication skills in children, while also reducing loneliness and social isolation in older adults. The potential to strengthen local community ties was also identified as a benefit of the program, although to a lesser extent for Older Adults (84%) compared with Parents (100%), Carers (96%), and the Other group (95%), (p = 0.04). Some participants were uncertain about aspects of intergenerational programs (with 11% and 5% of the Older Adults, 13% and 3% of the Parents, 9% and 11% of the Carers, and 17% and 10% of the Other) thinking it could be emotionally draining and could create conflict between people, respectively. Despite the concern there was strong interest in participating in intergenerational programs with 68% of Older Adults wanting to participate themselves and 77% of the Parents group willing to enroll their child or grandchild. Over two-fifths (43%) of Carers were interested in having a relative or care partner participate. For those interested in participating, they generally identified more than one reason, with the main reason differing between groups (Figure 2). Older Adults, 78%, chose experiencing something new as the most important factor. Parents, 93%, indicated they were interested in giving back to the community; while 86% of participants in the Carers group were interested in the social element and 89% of the Other group were interested in giving back to the community. Similar proportions of Older Adults (16%) and Parents (10%) said they were not interested in participating, or did not know someone who would be (p = 0.45). For the Older adults being too busy and already having enough contact with people of other ages were the main reasons given although numbers were small.

Figure 2.

Participants reason for taking part in a program.

3.1.3. Practicalities of Delivering Intergenerational Programs

Participants were open to a variety of locations for in-person programs. An early childhood center was the most common location chosen by Older Adults (82%) and Parents (87%) as a comfortable place to participate; while 84% Parents indicated they would also be comfortable at a residential aged care facility. More than two-thirds of participants in all four groups said they would be comfortable at a community hall. Only about half of the participants said they would be comfortable at a research or educational institution like a university, and less than half preferred a function room at a hotel or restaurant. Participants were ambivalent towards using a space in a religious building, with 55% of Older Adults, 32% of the Parents group, 38% of the Carers group, and 47% for the Other group being comfortable with the location, though the difference in proportions did not reach statistical significant (p = 0.20). Interest in participating was generally higher for those living regionally than those living in city environments. Half (49%) of those living in regional areas compared to 37% of those from major cities were interested in participating themselves, though the difference did not reach statistical significant (p = 0.21). Nearly two-thirds (63%) of those living in regional areas compared to 23% of those from major cities were willing to enroll their child or grandchild (p < 0.0001). There was also a smaller proportion of participants from regional areas (11%) who had no interest in participating, or did not know someone who would be, than in major cities (29%) (p = 0.04). The greatest barrier to participating in the program was time, particularly for the Parents group as indicated by 82% of respondents in that group (Figure 3). The preferred option for all four groups (32–50%) was to meet weekly for an in-person program, with the meeting ideally lasting 1 h (39–55%); although, almost as many of the Parents group (29%) were in favor of a monthly meeting. Transport and financial costs were the other main barriers to participating in this program. The preferred mode of transport for all four groups was private transportation (66–87%), with travel times that are between 15 and 30 min duration (52–61%). Financial cost was indicated as a barrier to participation for similar proportions of the Older Adult group (32%) and of the Parents (29%) (p = 0.76), which was complemented by similar proportions of the same groups (61% and 71%, p = 0.37), indicating they would be willing to pay to participate in an intergenerational program.

Figure 3.

Barriers to the participation.

3.2. Study 2: Semi-Structured Interviews with Community Members

Ten older adults and eleven parents of pre-school children were interviewed. The top-level findings from the interviews are reported here in relation to the participants; their prior knowledge of intergenerational programs; what they perceived as the benefits; loneliness and social isolation in the community (and responses to COVID-19); the types of activities participants thought would be appropriate; and the logistics and concerns relating to an international program.

3.2.1. Participant Background

Older Adults

All older adults were in favor of intergenerational programs and interested to take part, although, some were “not sure what they would get out of it” or “what they had to offer the children”. The age range was between 64 and 86 years. Only two of the participants were male. They primarily lived in and around the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney, Australia. All interviewees suggested they had socially rich, busy lives and were physically active. The cohort of older adults included people who had migrated to Australia from the UK as a child, a woman whose friends “changed their mind” leaving her to journey to Australia alone at 21, people who migrated with young families and people whose first language was not English. The cohort also included people who had “grown up on the beaches of Bondi and Coogee” and in nearby suburbs. The older adults had lived in the area for between 19 and 50 years.

None of the older adults had a formal carer or acted as a formal carer to others. However, two people spoke about medical conditions where they had been reliant on others for short term care. Some of the cohort had health issues relating to heart disease, cancer, osteoarthritis, and knee and hip replacements, some had experienced a general reduction in mobility, but none were immobile. Two older adults commented on perceived cognitive impairment in relation to a friend. Several participants were volunteer carers supporting friends, family, neighbors, as well as people with disabilities and in aged care facilities. They drove people around, made meals, talked, and kept them company, and helped navigate the bureaucracy of the health and aged care systems.

The older adults interviewed had had a wide range of careers including being on the local council, working for government, working at the stock exchange, in aged care and community centers, and being in the Royal Airforce. The cohort included teachers (‘kindergarten and school of the air’), academics, nurses, accountant, journalist, arts reviewer, radio operator in communications, and the head of a large retail organization. They had lived and worked in a wide range of places in Australia including Queensland and the Northern Territory with Aboriginal communities, and overseas noticeably New York and Antarctica. They had been keen sports people; surfers, cricketers, and footballers. Their education levels varied from leaving school at age 15 to postgraduate degrees.

The cohort included people who were married at 19, those who first married at age 50, and people with several marriages, divorces, and partners. There was a balance between participants who lived with a spouse or partner and those living alone. Some participants were in shared accommodation with close friends having decided that this would be a good arrangement after divorce or being widowed. Two people who lived alone, proactively commented that they liked it that way and enjoyed their own company. Nine people interviewed had children, but only one had an adult child living at home. They had a wide range of life experiences such as dealing with alcoholism, divorce, not being able to have children, being single parents, bringing up children with diverse needs and in marginalized social sets. They also had a wide range of experiences from their working lives and travelling overseas.

The cohort appeared for the most part motivated, articulate, and confident. They recognized limitations of ageing but also benefits. One participant mentioned, “I was scared [when younger], but now I’m not scared of anybody or anything, now so it’s alright!”, several others commented on how they enjoyed their own company now, and the company of longstanding friends.

Parents

While all the parents interviewed had children at the same pre-school, their social, economic, and cultural backgrounds were diverse, as were expectations of the benefits of an intergenerational program. All children of parents interviewed were between 3.5 and 4.5 years old. Out of the cohort of eleven interviews, three fathers were interviewed, one alongside the mother of the child. As with the older adults the parents had a wide range of experiences. Some parents were new to the area whereas most had been in the area between five and fifteen years. Parents were from China, United Kingdom, America, Brazil, New Zealand, South Australia, Queensland, regional NSW, Western Australia, and the Bondi and Coogee area. In all but two cases both parents had jobs or careers, but in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic it appeared that in all but one case, at least one parent was working from home. Two people reported they had lost their jobs because of the pandemic. Careers included Lawyer, IT specialist, aged care worker, occupational therapist, teacher, yoga teacher.

The primary topic of conversation for all parents was family. They provided information about their immediate family, extended family, life experiences with family, and what was perceived as missing in their family. While all interviewees now lived within a five-to-six-kilometer radius of the venue where the pilot program was to be run (and most within 1–2 km), their experience of family differed significantly. Only one couple had both partners who had grown up in the area. Most couples included at least one person from another town, state, or country. In three couples, the partners had immigrated to Australia together. Experience of ‘family’ varied from a very large close extended family in Brazil, for example, to being brought up an “only child in a very nuclear family’ in Australia. One person grew up “on the land” where they relied on neighbors and friends who were in effect like an extended family. Some parents interviewed had experienced the sickness and death of one or both parents, sometimes leaving them with no extended family in Australia or overseas. In most circumstances extended families did not live in Australia and many were overseas. The COVID-19 pandemic global lockdowns meant that visits to or from parents or extended family were no longer possible, and grandparents visiting their family from China, were not able to return home.

Families included full-time working mothers and fathers with four children, and in one case three children under five. Most of the children had at least one sibling. All but one of the parents interviewed were part of a couple, several had been divorced—with children from a previous marriage being part of their current family unit.

3.2.2. Experience of Intergenerational Programs

Participants knowledge of intergenerational programs, in all but one instance, came from watching or hearing about the television show Old Peoples Home for 4 Year Olds in the UK and Australia ((, ; , ). Those who watched the show gave an example of something they remembered seeing on the show, such as “the old grumpy man who came round in the end”.

3.2.3. Benefits

Everyone interviewed suggested that there were benefits in intergenerational programs. Parents were very clear that older adults would benefit from “just being around children”. The primary benefits for older adults, from the parents’ perspective, was proximity to youth, fun, enjoyment, listening to the funny things that children say, and fulfilling a substitute role when older adults did not have access to their grandchildren. Most parents thought the greatest benefit in the program would be for the older adults, because they perceived them as being lonely or isolated. One parent suggested “We are doing it for the old folk, I don’t think [she] will get anything out of it, really”. It became apparent that some level of stereotyping was occurring with comments from parents about the “poor old folk” and in not associating childlike (playful) behavior with older adults except in the company of children, “Really, older people are not children, and they don’t act as children, but they sometimes do when they’re with a child, you act as a child.”

The perceived benefits to the children, from both the perspective of older adults and the parents of the children, primarily focused on the concept of transference of wisdom, suggesting that older people had knowledge, and experience that they could pass on, they could inform children about “the old days”, and provide insights into “the way things used to be”. Storytelling and relating past experiences were seen to be key elements of any engagement.

In many cases older adults were perceived as substitutes for absent grandparents, making up for the loss of not having an extended family close by, suggesting, “Certainly, I believe that if my children were around their grandparents, it would be a huge benefit to them” and “One of the reasons I really like the idea of the program … she gets to spend some time with some older people, and she doesn’t get to see Nana and Grandad much, so it’s a bit sad”. Parents also thought the intergenerational engagement would build their child’s confidence, particularly in engaging with people who were not part of the family unit. A smaller, but impassioned number of parents viewed the program as an opportunity for their child to engage with older adults as friends, and be exposed to different types of people, different needs, and to experience social and cultural difference. For example, “I think generally they [older adults] have something to offer, that tired and cranky parents don’t” and “I think kids benefit from other adults outside of their family being involved in their life, regardless of their age”.

Older adults were less clear about the benefits, with one person stating that, “he was not sure what he would get out of it” and “not sure what the children would get out of it”—but he reiterated there was a benefit. Several older adults suggested that intergenerational projects were for the very old, and they were too young to benefit “I don’t feel that old?” and were surprised to be thought of as “old”.

3.2.4. Loneliness and Social Isolation

Participants were asked whether they had experience of loneliness and social isolation or recognized this in the community. While both older adults and parents suggested there were many “poor older people out there who were lonely and isolated”, few older people expressed first-hand experience of being lonely, and few parents could identify anybody they knew who was lonely. For the most part conversation here focused on the impact of COVID-19. Responses to questions about COVID-19 lockdowns, loneliness and isolation were (surprisingly) upbeat. Most participants, both older adults and parents, suggested that COVID-19 had not impacted them greatly, but suggested that they believed that it had a “great impact” on other people.

Parents welcomed the time regained from not taking children to activities such as sports and dancing. They welcomed the shared time together and found new activities to do—such as one family bought scooters to go out in the evening when less people were around. Most parents viewed the time as a “circuit breaker”. They were spending more time at home and more time with their children. It made them “rethink the way we live”. It also caused parents to think more about family connections. People missed seeing their extended families, but it was apparent that they were now using tablets and smartphones for long distance communication on a regular basis.

Few older adults reported being personally lonely or depressed but suggested there were a lot of lonely and socially isolated older people “out there”. Some suggested that “neighbors” or “friends” were lonely, but when pressed further did not know anyone specifically they would class as lonely. Most people interviewed had a small circle of friends that they kept in touch with, visited in their homes or went for walks with. Only two people thought the lock down was “dreadful” and one person who had quite enjoyed it, suggested that their partner had the “heeby jeebies” now and then. Older adults suggested that it had curtailed some of their socializing and that they were seeing friends less frequently. They were compensating for face-to-face contact by, for example, now playing bridge online rather than meeting up physically. One older adult explained that he was “feeling a little lonely as he was not able to call into the local club to meet people casually”. He now had to plan meetings and that was not as easy to do. These issues were conveyed as minor inconveniences. Several people suggested that they liked their own company and did not mind not socializing. This included a man who had once spent 15 months in the Antarctic with few people for company, and a woman who usually had a very busy social life who now enjoyed being under “no pressure to go out and socialize.”

3.2.5. Activities

In response to what type of activities would be good for an intergenerational program, both older adults and parents focused on sedentary activities such as reading, storytelling, craft activities, art, card games, and “old games” such as Ludo (a popular twentieth century board game). Older adults talked about activities they did with their own children and grandchildren. A couple of older adults expressed concerns about their mobility and health issues, and about the children being “so active”. They suggested they would enjoy just “sitting together”. Most parents thought that the activities should be educational for the children, should be part of the preschool curriculum, or wanted the older adults to teach the children. They wanted to build relationships where the child would learn from the adult and benefit from the imparting of wisdom. Parents also thought that their child would be able to teach the older adults how to do “new things”.

3.2.6. Logistics and Concerns

Both older adults and parents found it difficult to imagine what format an intergenerational program might take. There was no consensus about what the duration of the program should be, suggestions ranged from three to four weeks to ongoing. The suggested length of each engagement varied from thirty minutes to three hours. Similarly, there was no consensus about the best time of day for an engagement, or the number of days a week. It was unanimously agreed that the chosen destination for the pilot program—at the church hall next to the pre-school—was ideal. This was primarily because it was familiar to the parents’, children, and older adults.

Response was mixed regarding how older adults and children should be introduced to each other. Most parents were keen to have their child paired with an older adult to encourage a special friendship, while others liked the idea that children engaged with several adults and “found a friend”. This raised concerns that some children would radiate to the same adult and some adults would not be picked. For example, two older adults were concerned that if the children were left to find a friend that they would not be picked because they were “racially different” or “just not that interesting, ‘cos children often take time to come around”. Two older adults expressed concern about how the children would behave, suggesting that different parenting styles might inadvertently impact the program. Parents were concerned that their children would develop relationships and be sad at the end of the program. Although most were pragmatic, recognizing this as a learning experience for the child “to understand that people and friends will come and go.”

4. Discussion

4.1. Study Profile and Aims

The survey advertisement attracted people who were within the demographics of participants of the planned pilot program, i.e., older adults and parents of 3–5 year olds. It included people who identified as carers (of children or older adults) and it attracted a group of ‘Others’. These were primarily women who did not identify as carers or parents but, are within an age group (most between 30 and 60) where they may have, or foresee, family responsibilities/commitments for children and or older parents and so have an interest in the potential of intergenerational programs. Interview participants identified as older adults or were parents of children 3–5 year olds.

All interview participants and most survey respondents were in favor of intergenerational programs and could see benefits, but not without some hesitation or concern. The concerns primarily focused on being time poor, activities being a chore or distressing, the location of the program and access and cost. However, overall connecting with others (seeing family and friends) was considered beneficial, and many respondents saw engaging in a program as a way to give back to the community. Interestingly in the survey, parents were less likely to see programs as a way of breaking down stereotypes.

4.2. Aligning with Pre-Existing Theorizing

Our study participants show how their preconceptions of intergenerational programs align with aspects of the limited theorizing that has taken place. For example, most comments from older adults and parents reflect contact and development theories by focusing on the importance of “just bringing young and older together” for an interactive engagement (). Parents focused on the educational opportunity for their child’s individual skill development. However, a small number of parents perceived opportunities to build social capital through raising their child’s awareness (; ).

4.3. Recruitment and Community Dewelling Adults

We chose to engage with and design an intergenerational program for community dwelling older adults with recruitment through a local church and associated preschool group. Our participants identified as active, independent, socially engaged in their longstanding communities, with agency over most, if not all, aspects of their lives. This contrasted with findings in existing studies which focus on aged care facilities and community groups with less autonomy over their day to day lives. While they reported living alone, occasionally feeling lonely, and only being isolated due to the COVID-19 pandemic, they also suggested they were very busy (“too busy”) and had ongoing support from friends and community organizations. Both the older adults interviewed and surveyed suggested that they wanted to engage in an intergenerational program to “experience something new”.

The participants self-selecting to be interviewed and who wanted to be involved in the pilot program reveal limitations in this study but also provide two important insights for the development of intergenerational programs. The first is that despite being busy, socially active, not being lonely or socially isolated, our older adults were all very keen “to try something new”, “give back to the community”, and spend time with children and engage with intergenerational programs. They challenged the stereotyping of older people not wanting to do new things and revealed a need and want for being more involved in the community and meeting new people. The second insight was that recruitment methods need to be carefully considered if programs are to really reach those who are most socially isolated and lonely as they are, for the most part, invisible in the community. If community based intergenerational programs are to be used for engaging with older adults most at risk of social isolation and loneliness, and in need of support to allay potential clinical and medical interventions, then appropriate recruitment strategies and tactics need to be developed (; ). Our findings show there is a distinct lack of discussion of recruitment strategies of community dwelling older adults in existing literature and that a general ‘call-out’ is unlikely to mobilize those who are less activated or motivated, so it may be important to draw on the support of, for example, care services operating in people’s homes.

4.4. Perceptions of Others and Possible Stereotyping

Our studies highlight a point of difference between how parents viewed older adults and older adults’ perception of themselves (as potential participants of an intergenerational program). Parents of young children inadvertently, in discussion, associated loneliness, socially isolation, health and mobility issues with all older adults, with little, to no, consideration of individual context or differentiation between those often described as the young old (60–70) and the old (85+). Parents were keen to participate in intergenerational programs primarily for altruistic motivations, to “give back to the community”, suggesting “we are only doing this for the poor old folk”. Commenting that, for example, their children were “delightful company” who could teach the older adults “new things” and encourage them to be playful and have fun. Here, we see an assumption that it was the older adults who would benefit most from any exchange between adults and children and while well-meaning these comments indicate unconscious stereotyping equating “old/older” with deficit regardless of context, and an underlying suggestion that playfulness or fun is not a trait of older adults, who need to be introduced to “new things”.

In contrast older adults saw the intergenerational program as an opportunity for them to contribute and “give back to the community”, rather than only benefit themselves. They wanted both to try new things and mentor, teach, build an emotional connection with the children, and have fun. Few older adults identified as being “old” but were accepting of being “older”. They were keen to show that they had fun in their day-to-day lives, were socially engaged, active, and mobile, had few health concerns and were not socially isolated or lonely. However, questions arise with regard to the extent to which older adults rejected any acknowledgment of being personally lonely and whether admitting to loneliness was seen as stigmatizing.

Possible stereotyping also occurred in relation to the roles foreseen for older adults and children in intergenerational programs, parents and older adults’ views differed. While some parents wanted older adults and children simply to be friends and for both to be exposed to diversity in age, ability, and background, most parents assumed the major benefit of a program for their child was in having substitute grandparents (). Older adults, however, reflected on how they engaged with their own children or grandchildren, but did not give any indication that they foresaw themselves in a grandparental role in intergenerational programs. As one person commented “… [parenting/grandparenting] was a long time ago and things will have changed”.

These findings are important for intergenerational programs that aim to support community needs regarding social isolation and loneliness and overcome stereotyping. “Doing it for the old folks” and assuming older adults will, and/or want to, to take on a grandparent role highlights a degree of stereotyping to be overcome. While supporting others may be the very impetus for parents becoming involved in a program in the first place, researchers need to ensure that in raising awareness and calling for participation they do so in a way that does not inadvertently reiterate the prejudices the programs aim to challenge.

4.5. The Role of Acitivities in Relation to Children’s Ages

Both the survey and the interview findings reflected the importance of social activities and meaningful engagement. However, our interviewees often had difficulty in foreseeing what type of activities older adults and young preschool children might do together. Some parents thought they should simply be fun, but most wanted “educational” activities such as older adults reading to children. Older adults who had taught, trained, and mentored also were interested in fulfilling such roles with the children in an intergenerational program. There were concerns that activities might be infantilizing or “Silly” with a recognition that the age of the children impacts the types of activities and engagements that children and adults can do together. For some social activities could be stressful, and the survey results also reflected concerns about intergenerational engagements being tiring, a chore, or even distressing. Not all parents assumed that the intergenerational engagement would be completely harmonious with some parents suggesting their children “could be a handful” and “who knows how they will respond to older adults”. For older adults one of the primary concerns was expressed as a vulnerability relating to the possibility of being rejected by the children due to ethnicity or language difficulties. Some were concerned that the children may simply just not like them, or that all the children would all like one other older adult (). More research is needed into the role of activities and how they build relationships, overcome stress, and change attitudes particularly in exploring what is appropriate for both older adults and children.

4.6. The Role of the Community

The data collection for the interview study and the planned pilot program centered on a parish church and Christian pre-school. While the survey revealed ambivalence towards programs being connected to a religious building, in this study the church provided access to the community—but was also likely as to why participants did not report being lonely or socially isolated. However, working with a third-party organization proved to be effective at motivating participants and is an important consideration as to what type of organizations to partner with to access those who will benefit most from intergenerational programs.

5. Conclusions

Most of the research into intergenerational projects has drawn from residential aged care facilities, adult day centers, and organizations who provide support for older people with care needs. It has a strong focus on overcoming deficits relating to ageing (impaired mobility, frailty, social isolation, loneliness, etc.) (). This study, to our knowledge, represents the first in-depth exploration of Australian perceptions of intergenerational programs in the community. As such, it provides unique and important insights to inform future research, adds to the growing body of knowledge indicating the importance of understanding this area and supports the development of such programs going forwards. This study engaged with people living at home, who were not part of pre-existing communities established through aged care needs. As a result, it points to some important challenges for intergenerational programs in the community, particularly in relation to recruitment and inherent stereotyping. While there is a wealth of positive reporting on intergenerational programs, being aware of the challenges is key to establishing robust research and sustainable community intergenerational engagement ().

To benefit those most in need in the community, intergenerational programs need to prioritize reaching further into the community to reach those who are not readily coming forward and are not yet visible and develop protocols accordingly. More research is needed with regard to the potential for stigmatization of admitting to being lonely or socially isolated, particularly in active communities, such as the one we were working with. There is a potential for, in positioning intergenerational programs as supporting people who are socially isolated or lonely, that it is becomes a deterrent for people who do not want to acknowledge this.

This study revealed the wealth of experience of the older adults. This is an aspect of intergenerational engagement that has not been fully explored regarding how older adults can be a resource in relation to the development of activities and the roles and relationships of generations. Both older adults and parents highlighted the importance of teaching, mentoring, sharing experience. The positioning both older adults as facilitator, mentor, teacher building on personal experience, and similarly encouraging children to ‘teach’, can overcome the risk of older adults feeling infantilized. Both parents and older adults supported more structured engagements, and this has implications for intergenerational program design and staffing.

This study has shown that there is an appetite for intergenerational programs in the community. It also reveals the importance of recognizing the many different contexts in which older adults and parent and children live, and the many varied backgrounds. It shows the need for a framework of protocols for programs that recognize different cohort needs (active able adults, frail, socially isolated, cognitively impaired engaging with pre-school children, playschool, etc.) and considers where when and how the interaction takes place. This is a first step in moving towards such a framework.

Author Contributions

G.K. co-conceived the research, carried out and analyzed the interviews and drafted the manuscript; N.E. co-conceived the research, co-designed the survey and commented on the manuscript; Y.X. co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; B.L.L. analyzed the survey data and commented on the manuscript; S.A.W. co-conceived the research, supported recruitment, and commented on the manuscript; M.B.G. co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; E.L. co-conceived the research, supported recruitment and commented on the manuscript; K.R. (Katrina Radford) co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; K.J.A. co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; N.T.L. co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; J.A.F. co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; K.R. (Kenneth Rockwood) co-conceived the research and commented on the manuscript; R.P. co-conceived the research, co-designed the survey and commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by funding from the UNSW Ageing Futures Institute, UNSW, Sydney, under an interdisciplinary fund scheme. The views expressed herein are those of the authors and are not necessarily those of the Institute.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical approval was granted by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Advisory Panel C Behavioral Sciences HC 3351 for an online survey, and HC 3368 for semi-structured interviews.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the authors for data availability.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Sematic and latent coding table.

Table A1.

Sematic and latent coding table.

| Category (and Node) | Sub-Nodes |

|---|---|

| !DEMOGRAPHICS | Age; background; Career; Carer; gender; Interview length; Life experiences; Reside—how long; Reside—where; |

| !PROGRAM LOGISTICS | Duration; don’t want it to end; duration—one off counterproductive; duration—3–4 months; Duration—after 10 weeks see you later; duration—continuing; Duration—ongoing; duration—school term time; duration—sessions; duration—six months; duration—terms; duration—semester; length of program; long-term commitment; more familiar vs lose interest; timeline; length of engagement; longer term; frequency; frequency—couple of times a week.; weekly; organization; logistics; organization—cost; organization—driving force; organization—transport; organization—whatever you think; organization—needs someone to drive it; research; lot of potential for recruitment; measures; research—part of experiment; research—recruiting people; research—successful project; research—whatever they tell us to do; Timing; afternoon; mid-morning; midday; middle of day; middle of the day; more energy in the morning; morning; not late afternoon; Timing—afternoon is nap time; Timing—afternoon nap; Timing—crazy after lunch; Timing—drop-in program; timing—include food lunch; timing—morning; timing—sleepiness after lunch; Timing—tedious too long for older people; timing—three hours too much; timing—time of day; timing—time to build rapport; Timing 10–1pm; timing longer period; when run program; venue; Venue—access; Venue—familiarity; venue—good location; venue—locality doesn’t matter where; Venue—Where; familiar; Good venue; logistics; pre-school is the perfect place for me; venue—good place; |

| Achieve | achieve companionship; achievement; |

| Activities | Activities—absorbing; Activities—building projects; activities—conversation while doing; Activities—crafting; activities—hearing stories; hearing stories; activities—interested in grandparents; activities—introduce old electronics; activities—learning into play; Activities—share great stories; activities—Simon says; Activities—sitting down exercises; Activities—story telling; Activities—surprise parties; Activities—table top activities; activities and learning—autism; activities play with hands; activity—engaging activity; activity—learning—trains and information; activity—Lego; Activity—singing dancing; Activity—yoga; Activities—every week activities; Activities; Activities—artwork; Activities—be involved in; Activities—blocks; Activities—books; Activities—cards; Activities—chalked outside; Activities—change activities; Activities—Children interest in learning; Activities—collage; Activities—coloring; Activities—coloring; activities—conversation; Activities—cooking; Activities—cutting and pasting; Activities—dance; dancing; activities—doing something together; activities—drama; activities—drama plays; activities—extended play; Activities—extracurricular cancelled; activities—finding out what grandparents interested in; activities—gym; Activities—hands on activities; activities—imaginative games; Activities—jobs around the house; activities—learning—view as teaching opportunity rather than social; activities—match with curriculum; activities—not just talking together; activities—not reading; activities—not singing dancing; activities—not sitting in front of TV; activities—not technology; Activities—not YouTube; Activities—one topic a day; activities—pass down stories; activities—physical activities; Activities—puzzles; Activities—reading; read books; activities—sharing; Activities—singing; activities—so long as it is fun; Activities—special outings; activities—sport; Activities—structured learning; activities—syllabus; activities—tactile; Activities—verbal story telling; activities—walk around block; activities—walking round the yard; activities—walking together; activities 0 sharing information; activity—stickers; activity—talk; Activity—playing; activities—sketching; allow for boredom; arts; background—likes tearing around and being energetic; backyard; busy; busy life; kids are already maxed; nothing to do; take time; tired; card; compulsory fun; cooking would be good; drawing; dress up; forced; games; Hands on; have a go; hobbies; hobby; listening to music; look at nature; magic tracks; making together; music and bringing together in nursing homes; New activity; no sport; not activities to do; not appropriate; not engage; not just passing information; not task oriented; Nursery Rhymes; outing or event; outside; painting; Physical; planned activities; play; problem; reading; scootering; sing; sport; stories; storytelling; strategy; talking; together; trips; want child to be bored; want to show things; writing; |

| Aged care | aged care setting; leisure living; Background—educated; |

| Behaviors | attention seeking; beautiful qualities; behavior—enthusiasm; behavior—Grandchildren—be ‘in’ with our grandchildren; behavior—our boy like reading; Behavior—reserved kids; behavior—she is lovely with people; Behaviors—alertness; Behaviors—aliveness; Behaviors—anger issues; behaviors—back off; behaviors—be jovial; Behaviors—be themselves; Behaviors—child enthusiastic; Behaviors—child may not gel; behaviors—children are accepting; behaviors—children do what they do; Behaviors—children funny; Behaviors—children may something rude; Behaviors—children saying things; behaviors—children shy; behaviors—children take lead; behaviors—confronted; behaviors—difficulty socializing; Behaviors—do what kids do; behaviors—does not interact; behaviors—does well with strangers; behaviors—don’t mix with old people; behaviors—don’t really want to be there; behaviors—ending relationship forget so fast; behaviors—energy; behaviors—energy they bring; Behaviors—engages with adults more than children; behaviors—full of energy; behaviors—goes a bit crazy; behaviors—must try it; behaviors—he will initiate conversation with adults not children; behaviors—manners; behaviors—mixes with adults but not older; Behaviors—older people wake up early; behaviors—racism; behaviors—say funny things; behaviors—say inappropriate stuff; behaviors—see different responses to actions; behaviors—see how he interacts with other children; behaviors—selfish—focus on me; Behaviors—selfish behavior; behaviors—sexism; place to go; politics; behaviors—shock; Behaviors—soak up a lot; Behaviors—they can be horrendous and exhausting; behaviors—they make you do things they do; behaviors—time to warm up; behaviors—try everything; behaviors—will not initiate social interaction; behaviors—will not keep interest; behaviors—will not leave our sides; bring life and light; cheeky; child brings joy;child talking and showing; confusing; cranky parents; crazy; cute; feral kids; grumpy; hard to control; interest; keep attention; kind; like; lovely; makes games out of everything; media; misbehave; miss; mutual support; no filter; patience; playful; playfulness; restless; rise to occasion; smile; stimulation; stunned; Take out; transition; unexpected; very active child; |

| Benefits | Benefit—I wouldn’t get anything out of it; benefit—mutually benefits; benefit—nurture each other; Benefit—rapport and having fun; Benefit—spend time with older people; Benefit for children; Benefit—build confidence children; benefit for children2; benefit from cultural change; benefits for children; broad demographic; experiences; insights; opportunity to extend personality; train her to be kind and gentle; We have thought about what child gives older adults; Benefit to older people; benefit for older people; benefits for older; Child in itself is the benefit; they will benefit from the child; worthwhile; benefits—hard to predict what they get; benefits—personal benefits from engaging with older people; Benefits—stepping out of problems concerns; benefits out way challenges; benefits—benefit; benefits—joint outcomes; most benefit for older adults; not much for short term; |

| Benevolence | benevolence—do something nice; benevolence—giving back to the older folks; |

| Busy | busy—slow down; busy—super busy parents; busy—time on my hands; Busy—trying to keep busy; Busy lives—full schedule; Busy—lives too busy; busy childhood; full schedules; |

| Challenges | Challenges getting them going; challenging; |

| Changes | change—kids continued going to childcare; change—less rushing; changed—not being able to travel; change—get out of environment; change—home learning; homeschool; homeschooling; change—impacted; change—life became simple; change—no travel; change—now venturing out; change life—juggle of work home; change of life—tough early on; change of life—recent move; change of life got used to it; changed life—reflection; changed life—simple life; changed way of life—working from home; work from home; working from home; coming out of covid; compromised; make effort to go out; moved—downsized; moving; |

| Children | better life; child hurting older person; child ill; child might be rude; child misses socializing; child takes bumps and knocks; childhood; children do not spend independent time with others I meet on their own; children get from adults; children in aged care; children in the everyday; children like consistency; children like looking at different things; children not a problem; Children view of old; strange; children visit; describe Children; invigorating; love; |

| Community | church; community (2); Community—bowling clubs; Community—clubs; clubs—Coogee has things out there; Community—Clubs—RSL; community—council; community—everyone is responsible; community—poor delivery services; Community—pub; Community—RSL Community; Community—to support St Nics; community—volunteering; community center; Community church; community need; community staple; community—Is it needed in Coogee; community—volunteer with community; community—not much on offer; local; local—expat communities; local govt; local learning; local—isolationism; Location—transient community; love Coogee; make up of population; makeup of the suburb; |

| Concerns | concern—Communicate—verbalizing discomfort; concern—don’t know what they are going to get out of it; concern—out of place; concern—scared; concern—some people not being chosen; concern—unnerving; concern—unsure about response; Concern—worried; concern—worried about not having skills; concern—what if people get left out; worry about children; concern about safety for older people (not child); concerned about wellbeing of older people; concern—not living in fear; concerns—what are they getting out of this; concerns about different views; |

| Connection | connected; connection—interact with neighbors; continued to have contact with people; |

| Context | context—depends on situation; context—Othering—they; context—recognition of older people needs; Context—she told them they are not allowed to travel; Context—substitution; fill a hole; not necessarily about being grandchildren; substitute; context—surrounded by adults; context—talk about older people as if not old; context—talk about older people as other; context—treating old people stupid; old; old people; old people are in Randwick; old people get from young; old view of children; older; older adults take lead; older benefit more; older get from children; older neighbors; older people don’t have much to do; older people get from children; older people give what parents can’t; older people in their life; older people irritate children; older people lonely; older people more relaxed; older people not family; older people offer; older people remembering what it is like to be a child have children; older people snapping or grumpy; older people want to be left alone; oldies; onus on older people; perception of old; poor old people; |

| Covid | being just family then push into preschool; Covid—adjusting; Covid—extra cautious; Covid—focused on kids; Covid—positive; Covid—Risk from daughter—doctor; Covid—staying indoors; COVID—then found amazing time for my family; Covid—UK covid; difference; effort; going out; holidays; impact on other people more; not at our shiny best; not our shining best; push back out; reassess; stay home; survived covid; thinking; |

| TV | visit; worry; |

| Cultural differences | Culture—different cultures might have problem; cultural difference—include dementia—for experience; cultural questions; Culture—difference accent; Culture—difference in color; different parenting styles; some places pat of the culture; take daughter into nursing home; |

| Development | develop fine motor skills; development—build self esteem; development—instill values; Development—respect; development—showing her she can; development—understanding nice to meet new people; Development—discovering things with older people; development—instill belie in self; |

| Emotion | Emotion—a pick me up; emotion—anxiety; emotion—bring joy; emotion—but see how they accept me; emotion—comfortable; emotion—confusion; emotion—depends on mood; emotion—discomfort; emotion—enjoyable; enjoyed; enjoyed it; emotion—feel good; emotion—grandchild hated me; emotion—happier; emotion—happiness on both sides; emotion—happy; emotion—joy; joy—when thinking about sickness and death; joy like grandchildren; joy of life; emotion—joys; emotion—laughter; emotion—proud; emotion—really enjoyed it; emotion—rejected; emotion—stimulating; emotion—vulnerable; emotional intelligence; emotional need; emotionally; emotions—being rejected; emotions—comfortable with uncomfortably; emotions—fearful; fear of the unknown; encouraging older people; enjoy; Enthusiasm; excited about; fun; funny; happiest; happy; humor; joy; laugh; sad; |

| Exposure | engage with different ages; excited to see what they get out of it; experience of older people; experience of people not in family; exposed to older people; expose children to life; exposing to older; exposure to different people; exposure—accepting; accept life is different; Acceptance questions around language and culture; exposure—appreciate every type of person; exposure—appreciation of children; Exposure—different perspectives; difference—broaden worldview; Difference—children need to see someone not like mom; Difference—exposure to new perspectives; different—around different people; different aspect; different from family; different perspective; different viewpoints; different views; different way of life; different with strangers; different adults involved in rearing; different background; parenting—different parenting styles; exposure—extend possibilities; exposure—if they don’t accept you no problem; exposure—perspectives; exposure—see impact; exposure—see what happens; exposure—widening perspectives; exposure—won’t call it out as different; exposure to older people; exposure to people outside family; listen to someone who is not parent or teacher; need to see people different ages and experiences; new opinions; new section of society; next adventures; |

| Family | different types of family; adoption; encourage friendship; Family—adult children; family—brother; family—close; family—hard on mothers; family—nephew; family—three boys; family closeness; family history; family life; family thing to do; Gay; have children; no children; single children; single parent families would benefit; Grandchildren; have grandchildren; no grandchildren; have grandparents; family—grandparents; family—working; family—didn’t see parents; grandparent type of relationship; grandparents close; marriage; divorce; family—single parent; husband; no extended family; families—aunties uncles—older people; Miss parents; No grandparents; no local family; |

| Govt and council | Gov; gov—contact being governed by govt; gov—not transparent; |

| Health | grief; Health—cancer; all clear; health—conversation more fragmented; health—dementia; Health—depressed; depression; doom and gloom; mental health; health—depression—sadness; sad; health—down in the dumps; health—get help; health—I like learning; health—impacts mental health; health—keep my mind going; health—older sickness; Health—painkillers; health—respite; health—see benefit for mental health for older people; health—sickness—Alzheimer’s; health—therapy online; health—trauma; Health and wellbeing—Autism; Appreciation; Health and wellbeing—beneficial for wellbeing; health related; deafness; dementia; disabilities; falls; medical systems; weight; health Sickness—after surgery; health—mental health services available; health—wellbeing—engaging with children is nice; healthy—secret to living longer; life more fulfilled; like looking after my grandchildren; like to be involved; little ones keep us going; low mood; Mobile—active; exercise; mobility; mobility—fit older swimmers; |

| Interacting | interact a lot; interaction should be systematic; interaction with children; Interactions—forced interactions; lack of interaction with others; more engagement with older; more interaction; more interactive; |

| Intergenerational programs | cross generations; intergeneration gym; intergenerational and autism; intergenerational interaction; intergenerational living; intergenerational program; intergenerational programs; intergenerational programs—TV show; accomplishment; intergenerational projects; intergeneration program; intergenerational program; intergenerational programs—what reasons; intergenerational; lot of contact with grandparents; not people in that age bracket; not thought; |

| Memories | memorable; memories—prompt memories; memory; memory—brings back memories; remember; |

| Mixing and matching | intervene; matching or mixing; match a child; match child and adult; matching and mixing; matching up; mix with all ages; mix with older; mix with older adults; mix with older people; mixed and matched; mixed with young and old; mixing matching; mixing—buddying up; mixing—coaxing; mixing—matching one to one; mixing—provide backgrounds; mixing matching; mixing—dynamics; natural flow; |

| Negative | maybe no benefit; might not want to be part of it; miss out; miss children; miss grandparents; miss seeing connection; missed childhood; missed friends; missed sports; missed structure; missed visiting; missing out; missing seeing the kids; negative—hard for everyone; negative—intense lockdown; negative—no short-term benefit; negative—somber environment; not benefit for me benefit for children; not happy; |

| Opinion | opinion—lack of information; Opinion—life experiences—went through the war; own position; viewpoint—alternative approaches; viewpoint—criticism that parents do not recognize older people; viewpoint—do my own research; viewpoint—resent lack of data; viewpoint—theory is sound; |

| Parents | loved by older people; lovely child; mothers will be problem; parental help; parenting styles—children more confident; parenting—my parents different; parenting—selected; parenting differences; Parents—trade with children; parents—treat child as young adult; parents—wacked on hands; parents rushing; parents want to be part of it too; Parents—modern parenting; realistic; inclusive; not always easy; other people had it worse; realistic about children’s behaviors; reality; realistic about children’s behaviors; suffering is part of it; understanding; wide demographics; |

| Perceptions | Parent’s perception of older—acknowledge background; Perception—Age related comment; can’t believe I am old; Perception—gender related; perception—life experiences—world closing in; perception—outside age range; perception of older people; Perception older people—single; |

| Positive | be there full time; great idea; lucky; make it happen; make it work; more family time; need in the community; nice idea; nice thing to do; no negatives; no traffic; not greatly impacted; not impacted to much; not overwhelming; Positive—absolutely good idea; positive—bit of a blessing; positive—doing quite well; positive—fortunate; positive—good for both; positive—good for me; positive—good things happened for children; positive—gratitude; grateful; positive—happy doing what I am doing; positive—hasn’t changed much; positive—haven’t affected us massively; Positive—it is brilliant; positive—keen to be involved; positive—no loss in taking part; positive—not impacted us; Positive—pay more attention to children; positive—people nice to each other; positive—people want to be involved; positive—please to see reactions; positive—Programs needed; positive—project needed play group; positive—satisfaction; satisfying; self-satisfaction; setting up for success; positive—Values—simple things mean a lot; positive for both groups; positive for venue; positive to project—draw into the concept; positive—extra excited about possibilities; positive—perfect; positive—Love the idea; potential; potential benefit; something special to create e connection; something to look forward to; super excited; take part; time on hands; Volunteer; want to be involved with older people; want to be involved; |

| Quit program | make you stop; not enjoying; stop—end program; stop—take out program; stop—verbally resistant; stop—Withdraw—didn’t like; stop—dealing with children; stop engaging; |