1. Introduction

The Yemen Dyslexia Association (

Emerson 2015) defines dyslexia as ‘A functional disorder of the left side of the brain. It causes difficulty in reading, writing or mathematics associated with other symptoms, such as weakness in short-term memory, ordering, movements and directions awareness’. People with dyslexia find it difficult to connect speech with writing because they have deficiencies in the phonological component of the language. The difficulty of accurately and easily deciphering can affect reading comprehension and vocabulary development. Spelling difficulties can affect the production of written speech as well. Within this context, dyslexia is not a sign of low intelligence, laziness or poor eyesight. On the contrary, it occurs in the whole range of mental abilities of the individual. According to the law on education of people with disabilities (Disabilities Education Act), the functional definition of dyslexia is ‘special learning disability’ (

Futterman and Futterman 2017).

It is a disorder in one or more of the basic psychological processes involved in understanding or using language, speech or writing and can manifest itself in the imperfect ability of a person to hear, think, speak, read, write or carry out mathematical calculations. The most persistent problem, however, seems to be diction (

Roitsch and Watson 2019). More specifically, when a student with dyslexia begins to learn how to read, they have difficulty with the level of voice or sound, which adversely affects spelling and reading. Secondary consequences may include reading comprehension problems and reduced reading experience, which may impede the development of vocabulary and background knowledge (

Roitsch and Watson 2019).

Dyslexia is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in children. About 5–10% of school-age children suffer from dyslexia, which is more common in boys (

Huang et al. 2020a); the aetiology and pathogenesis of dyslexia have not yet been clearly defined.

Rüsseler et al. (

2017) have found that children with dyslexia may be associated with genetic and/or brain injuries, brain dysplasia, malnutrition and so on. External factors, such as school, family environment, childhood education, living environment and other factors, can also affect children’s reading skills. According to

Huang et al. (

2020b), children’s living and learning environment has significantly affected their learning skills. The result is that children with dyslexia have negative emotions about their self-image and relationships with classmates and family. In terms of social interaction, children with dyslexia lack social skills due to stress or low self-esteem and have problems with adapting themselves to social circumstances (

Abd Rauf et al. 2020). Additionally, the incidence of anxiety and depression in children with dyslexia is also higher than in typical children, with more negative behaviours, higher suicide rates and increased antisocial behaviours (

Abd Rauf et al. 2018).

Muhamad et al. (

2016) support that ‘teachers enjoy teaching maths to students with dyslexia but find that adequate training, teaching experience, and exposure to multiple teaching strategies are required for success’. According to

Macrae et al. (

2003), the student may also have difficulty with numerical facts, retrieving the theorems and the formulas that are needed and even more with mathematical relationships. In multi-step problems, students often lose their way or skip sections and do not consider all the relevant aspects of the problem. This results in their inability to make the necessary combinations and achieve a final solution. In support of this,

Witzel and Mize (

2018), in their research, corroborate that having legislative support for students with dyslexia and dyscalculia is beneficial. Employing empirically validated assessments and strategies is even better. According to them, teachers and teacher candidates alike must learn how to evaluate and guide students with dyslexia. In addition, in real teaching situations, dyslexic students appear to have less potential when asked to address certain assignments. Additionally, mathematics is reinforced through practice. For this reason, towards the end of a lesson the teacher often assigns a handout or some exercises from the official textbook for students to complete at home. While typical students may have completed the task before the next lesson, the dyslexic student will have completed perhaps three-fourths, and, in effect, they receive less reinforcement. This leads to a decrease in the student’s confidence in their ability to complete a set task. Furthermore, as

Grehan et al. (

2015) state, there is no one standard approach to providing support in mathematics which will cater for the needs of all students.

Macrae et al. (

2003) state that dyslexia may also cause slow reading, or the student may not understand what they have read. Finally, frequent problems arise when learners are asked to associate a concept with its symbol or function.

All the aforementioned reasons attest that a significant number of students with learning disabilities have certain difficulties in mathematics.

Cook et al. (

2019) state that ‘the research in mathematics is underdeveloped in such a way that special educators as well as general educators must make instructional decisions based on the best evidence when planning instruction for students with learning disabilities’. These students’ have difficulties in assimilating and understanding at the same pace during the lesson. Frequent repetitions are needed and, of course, someone who explains what the teacher says in simpler ways. In another study (

Shin and Bryant 2016), it is mentioned that students can become more proficient problem solvers if they are able to use models to represent the structure of the problem in a diagram or graphic organizer. Researchers (

Bryant et al. 2014) have pointed out that even the most struggling students can benefit from a small group intervention that is intensive, strategic, and explicit. Furthermore, according to

Robinson (

2017), effective models of inclusive teacher education will be likely to adopt a collaborative approach to professional learning and development. So, common educational programs for different groups of people with special educational needs are likely to be found, to a greater or lesser extent, in every educational system. Educational programs can be used in every level of education so that they can help students with special needs. For example, in schools with a large student population, the number of students with special needs is adequate to form homogeneous classes of learners who share the same level of learning difficulties. However, in educational systems which have only recently begun to provide targeted special education services to people with physical, mental, and multiple disabilities, this situation is increasing dramatically. An example of such a system is the Greek education system. In the last decade, it has been observed that the number of students with physical, mental, or multiple disabilities participating in educational programs of the Ministry of Education, mainly at the level of secondary education, has multiplied (

Papadimitriou and Tzivinikou 2019).

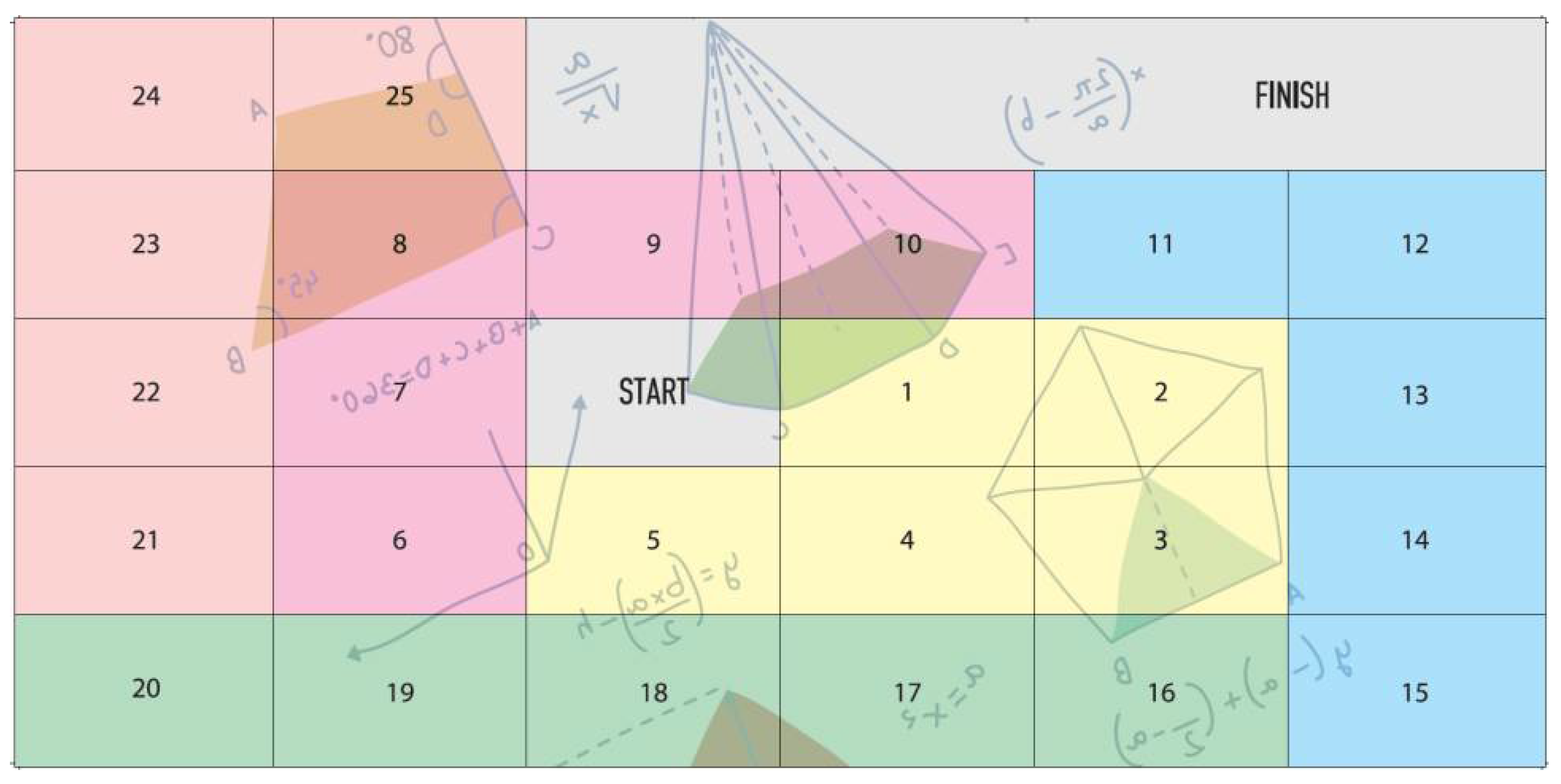

This research aims to investigate the effectiveness of the APS of the Greek Ministry for students with dyslexia in the course of mathematics in high school. In the same vein, it is directed towards indicating the need to design more comprehensive analytical programs for dyslexic students or to improve and supplement the existing ones. Accordingly, the grounds towards more effective teaching of mathematics to students with special needs will be set. Furthermore, it must be mentioned that a comprehensive presentation and comparison between an intervention in mathematics with the Adapted Analytical Programs for students with dyslexia is included. This happens because, in Greece, there are two analytical programs for every subject, one for students with special needs named ‘Adapted Analytical Programs’ (A.A.P.) and one for typical students named ‘Analytical Programs’. The A.A.P. for students with special needs, which refer to dyslexic students as well, contain exercises with graphs and pictures. The Ministry of Education publishes them to guide the teachers on how implement each lesson.

4. Discussion

The exercises carried out during this research were adapted to the needs of dyslexic students. Performing mathematical activities is a complex process that requires the use of many different skills. More specifically, the enhancement in all five learning areas helped each student to develop their mathematical abilities, but also to exhibit further enhancement in the corresponding areas.

The research questions of the study were confirmed, since the performance of student with dyslexia who participated in the intervention project was enhanced in comparison with the control group. In contrast, although the A.A.P. also increased the mean of the performance of dyslexic students, the increase in the mean was less than that of the intervention. The findings of

Bryan et al. (

1991) confirm how salient it is for dyslexic students to be integrated into special education programs due to significant differences between skills and mathematical performance. The findings of

Choi et al. (

2016) in this investigation indicated that this approach to inclusive education may benefit all students by improving student academic performance. Within the same context,

Tam and Leung (

2019) argue that students who showed some benefits in improving their behavioural and cognitive aspects required continuous intervention courses to become self-regulating students, develop self-motivation in order to improve, optimize on the learning methods, and adopt strategies in order to achieve academic goals. It should also be mentioned that these results confirm older research findings showing that teaching interventions based on the use of alternative games are more effective than a conventional type of interventions (

Shu and Liu 2019;

Kim et al. 2017;

Fokides 2017;

Al-Azawi et al. 2016;

Ke and Abras 2012;

Kebritchi et al. 2010;

Kiger et al. 2012;

Kim and Mido 2010;

Shin et al. 2011). Additionally, dyslexic students can benefit from the A.A.P., especially if they are adapted in alternative methods of teaching, such as a board game with cards.

Yeo et al. (

2015) in their research also supported that students made significant improvements across all topics of mathematics through an intervention program. Generally, in the present study it is shown that dyslexic students learn from an educational game, changing their cognitive and affective measurements. This fact is in line with the proposal of

Kim et al. (

2017),

Kraiger et al. (

1993) and

Castellar et al. (

2014) who support that mathematical games can increase mental calculation speed in a similar way as an equivalent number of paper exercises. It is suggested to design games in a way that students’ perceived competence, particularly in-game competence, will be increased so that they will be more engaged in game-mediated learning, thus benefiting more from games.

However, in Greece, according to

Stampoltzis and Polychronopoulou (

2009), research on dyslexia is limited. There is no project that uses an alternative intervention to teach mathematics to dyslexic students of high school ages. Therefore, in the present study, the researcher aims to supplement the existing literature and at the same time shed some light on the effectiveness of an alternative intervention in teaching and learning mathematics for dyslexic students by providing them with different stimuli. This fact, after all, demonstrates the innovation and the importance of the implemented intervention, which if accompanied by the A.A.P. will be of great benefit to the dyslexic students.

Furthermore, using hypothesis testing for the intervention, clear conclusions can be drawn about the design. Firstly, dyslexic students were improved greatly in all the cognitive areas to such a degree that it is considered statistically significant. Secondly, both methods of teaching enhanced the performance of dyslexic students.

Based on the above conclusions, the intervention has positive results in dyslexic students, but this does not mean that modifications are not allowed. Modifications are needed for the techniques used and related to the specific questions in which the dyslexic students did not show much improvement. This fact, however, is not discouraging because there has been not only overall improvement of students, but also improvement in each focused category of the game separately. Therefore, the intervention may be improved in the future only if some corrections are made, for example the sample increases with the number of the participants, changes in the card content of the game which are included in the intervention, and in the method of teaching through the cards. As

Papadopoulos (

2010) notes in his statistical research, the intervention can be improved by reducing the variability while keeping the sample size constant. However, this is not possible in our case, while the results are collected and analysed exactly as the students gave them. So, a practical solution would be to increase the sample size. In this way, the variability will be reduced. Furthermore,

Sabri and Gyateng (

2015) state that the chance of detecting a strong statistical difference will be increased by picking a large enough sample size. In conclusion, it is worth noting the difficulties and limitations of the research. Initially, collecting the sample was not easy because many school principals presented concerns about the time and the day that the students were going to participate and thus disagreed with the research process. In addition, some students wanted to leave the class because they felt tired or anxious about their performance, even though they knew in advance that the process was anonymous and their performance would not be graded. Another shortcoming was the fact that, many students with dyslexia needed more time to complete the pre- and post-test. Finally, increasing the sample, adding new cards, or modifying the existing ones in the board game may lead to safer conclusions. This fact is relayed to the improvement of the value of Cronbach’s Alpha in case of the removal of one card.