Abstract

Many scholars view the choral synagogues in the Russian Empire as Reform synagogues, influenced by the German Reform movement. This article analyzes the features characteristic of Reform synagogues in central and Western Europe, and demonstrates that only a small number of these features were implemented in the choral synagogues of Russia. The article describes the history, architecture, and reception of choral synagogues in different geographical areas of the Russian Empire, from the first maskilic synagogues of the 1820s–1840s to the revolution of 1917. The majority of changes, this article argues, introduced in choral synagogues were of an aesthetic nature. The changes concerned decorum, not the religious meaning or essence of the prayer service. The initial wave of choral synagogues were established by maskilim, and modernized Jews became a catalyst for the adoption of the choral rite by other groups. Eventually, the choral synagogue became the “sectorial” synagogue of the modernized elite. It did not have special religious significance, but it did offer social prestige and architectural prominence.

1. Introduction

The synagogue was the most important Jewish public space until the emergence of secular institutions in the late nineteenth century. As such, it was a powerful means of representation of the Jewish community in its own eyes and in the eyes of the non-Jewish population. With the advance of modernity and the growing integration of Jews into European societies in the nineteenth century, the Reform movement in Judaism emerged and strove to reconcile the Jewish religion with modern norms. Alterations of synagogue worship was a very important aspect of all versions of religious Reforms.

The question of whether the Reform movement existed in Tsarist Russia has much greater significance than it may seem at first glance. In addition to the obvious importance for understanding Russian-Jewish history (or the history of the Jews in Russia), the question plays a role in conceptualizing the Jewish past as divided between two paradigms: the modern, emancipated, prosperous, acculturated, even assimilated Jewry of the West, as opposed to the traditional, downtrodden, poor, authentic Jewry of the East. In other words, if the Reform movement existed in Russia, then Russian Jews would be identified as more similar to their western counterparts.

There were, until now, two scholarly approaches to the development of the Reform movement in Russia. Paradoxically, both were formulated by Michael Stanislawski in two successive sentences in his book Tsar Nicholas I and the Jews. Stanislawski stated that reform “trends in worship and belief [in Russia] never developed into a full-fledged Reform movement on the German or American model”, but for “a small segment of the society, religious reform was an important and longevous force in Russian-Jewish life” (Stanislawski 1983, pp. 140–41).1 The first part of this formula was accepted by Michael Meyer, the author of a study on the history of Reform Judaism (Meyer 1995). He concluded that “Jewish religious reform in Russia [was] ultimately episodic and peripheral, a possibility only very incompletely realized” (Meyer 1985, p. 86; cf. Meyer 1995, p. 200).2 The idea that the Reform in Judaism was only an episode was rejected by Mikhail Polishchuk, author of a book on Jewish communities in Novorossia (Polishchuk 2002). Polishchuk stated that the Reform “could be defined as a trend, that is goal-oriented actions; but, the scale of this trend, at least in the south, shows that it was in an embryonic stage” (Polishchuk 1999, p. 32).3 Nathan Meir, who studied the Jews of Kiev (Meir 2010), also arrived at the conclusion that “the trend never became a discrete movement with a developed ideology” (Meir 2007, p. 624).

Currently, Ellie Schainker is working on the subject of Jewish religious reforms in Imperial Russia (e.g., Schainker 2019). In anticipation of her study, the present article concentrates on the analysis of one facet of this question, namely the choral synagogue, which is usually perceived as a kind of Reform synagogue in the Tsarist Empire in the second half of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Although the term, in the direct sense, refers to the use of a choir during worship services, in reality there was an entire range of alterations that distinguished worship in a choral synagogue from that of a traditional eastern European one. Many excellent researchers who touched on the issue of those alterations did not hesitate to call them Reform without special discussion, pointing at the influence of Reform communities in Germany (e.g., Zipperstein 1985, p. 56; Nathans 2002, p. 146; Kleinmann 2006a, pp. 309–40).

The present article approaches the question differently, concentrating on the architecture and arrangement of space in the choral synagogues of Russia.4 I begin with the history of choral synagogues in its geographical dimension and I argue that the Main Synagogue and the Brody Synagogue in Odessa, the Oranienburger Straße Synagogue in Berlin, and later the Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg had a profound influence on the architecture of choral (and other) synagogues in Russia. Second, I examine the external signage that was used by the founders in order to set up a respectful place for those synagogues in cityscapes. Finally, I discuss the features of worship in choral synagogues in Russia in comparison to the Reform synagogues of central Europe, and I argue that the differences between choral and traditional synagogues were mostly esthetic with no denominational implications. Choral synagogues in Russia served the modernized and elite sector of Jewish society and not a certain religious movement.

Any analysis should start with the name itself. The term “choral synagogue” seems to be used almost exclusively in the Russian Empire.5 Probably its origin is the Yiddish khor-shul, that is, a synagogue with a choir, which was rendered in Russian as khoral’naia sinagoga. The Hebrew press of the second half of the nineteenth century did not succeed in finding a suitable name for such synagogues and inconsistently used all kind of translations, which were sometimes accompanied by Yiddish explanations in parentheses. The Reform synagogues in Germany and Austria-Hungary were often called Tempel, to stress their difference from traditional synagogues and their equality with the Jerusalem Temple. In Russia, this term was usually applied to Reform synagogues abroad and as a generic term when speaking about the Reform movement. Only rarely was it used as a proper name of a choral synagogue in Russia, mostly in the late 1860s.

The term “choral synagogue” was not used in Congress Poland and thus the region falls outside of the scope of this article. In general, the place in Russian-Jewish history of the Russian-ruled Polish territories presents a conceptual and methodological problem. On the one hand, synagogue reforms began in Warsaw as early as 1802 and Poland had direct and strong connections to the centers of Reform Judaism in Germany. On the other hand, the Great Synagogue on Tłomackie Street in Warsaw was a powerful model for some Jews in Russia, especially from the late nineteenth century. Therefore, without discussing the developments in Poland in detail, I will refer to Polish examples when necessary.6

2. History and Architecture of Choral Synagogues in the Russian Empire

Synagogues that differed from the traditional ones appeared in the Tsarist Empire as a direct consequence of the Jewish Enlightenment movement, the Haskalah.7 Its adherents, maskilim, harshly criticized contemporary eastern European Jewish society, and their critique included disapproval of traditional synagogues and the behavior of the worshippers there. For example, one of the central figures in the early Haskalah in Russia, Isaac Ber Levinzon, wrote about the traditional synagogue in the 1830s thus: “There is no order in the worship, one disturbs another, one builds and another destroys, one cries and another dances, one proclaims his loss and another smokes tobacco, one eats and another drinks, one starts his prayer and another ends his prayer” (Levinzon 1878, vol. 2, p. 131; cited in Zalkin 2009, p. 387n10). Similar texts, disapproving of the disorder, raucousness, and filth, and often mocking traditional cantors, continued to appear in maskilic Jewish newspapers to the end of the nineteenth century (e.g., D. 1864; Jonathansohn 1872; Ben-Adam 1890).

“Improvement” of worship was part of the maskilic program. According to the historian Israel Bartal, Haskalah “aspired to shape a new type of Jew who would be both a ‘Jew’ and a ‘man’” (Bartal 2002, p. 91) and maskilic synagogues aimed at combining Jewish and “universal” features. For maskilim, a separate house of prayer would fulfil three main objectives. The first was to create a place where they could meet and worship in the company of similarly minded people. The second objective was to build a model of edification for other Jews who would learn the dignified form of worship. The third objective was to present Jews and Jewish worship favorably in the eyes of non-Jews. Thus, maskilim desired forms of worship that fit the norms—real or imagined—of non-Jewish “civilized” society. The choral maskilic synagogue was intended to be a new Jewish space arranged in such a way that would discipline worshippers and help them transform into a new type of “modern” Jew. The Reform synagogues of the “civilized” Jews of central Europe served as the model.

The first Reform synagogues in Germany were mostly private, and the main communal synagogues introduced reforms later. From the mid-nineteenth century, however, it was the adherents of orthodoxy who split from the communal synagogues and established their own houses of prayer.8 In the Russian Empire, there was a different pattern. In Lithuania and Right-Bank Ukraine, the maskilim could not influence the existing synagogues and the only option for the introduction of “enlightened” worship was to establish private synagogues, belonging to a private person or group of people. In the south, however, the introduction of alterations into the communal synagogues became possible from a relatively early stage.9

2.1. Odessa and the South

The first maskilic prayer house in Odessa, which subsequently became known as the Brody Synagogue, was opened in 1820 by immigrants from Galicia who did not want to pray in the communal Main Synagogue.10 After the establishment of a modern Jewish school by the same group of Galician Jews in 1826, the prayer house functioned on the school premises (Polishchuk 2002, p. 25).11 No information about the character of the prayer house has survived, but its placement in a school headed by prominent maskil Bezalel Stern could indicate that it was run in the maskilic fashion. In 1841, the Brody Synagogue moved to a separate, though rented, building; hired a cantor, Nissan Blumenthal; and formed a permanent choir to accompany him (Tzederbaum 1889, p. 1).12 Its declared goal was to draw Jews closer to the enlightenment and to bring about a change in Jewish behavior through the introduction of “silence, order and decorum, as common in the best Austrian synagogues” (“Odesskii vestnik” 1841; cited in Gubar’ 2018, p. 251). In 1847, the Brody Synagogue moved to a new space, also rented, but “purposely arranged”, with a women’s gallery—this is probably the first mention of a women’s gallery in Russia (Belousova and Volkova 2002, p. 3; Gubar’ 2018, p. 233). As emphasized by historian Steven Zipperstein, the Brody Synagogue—the synagogue of the elite—“within a few years … became the model for Jewish prayer in the city, and the older Main Synagogue was transformed in its image” (Zipperstein 1985, p. 57).

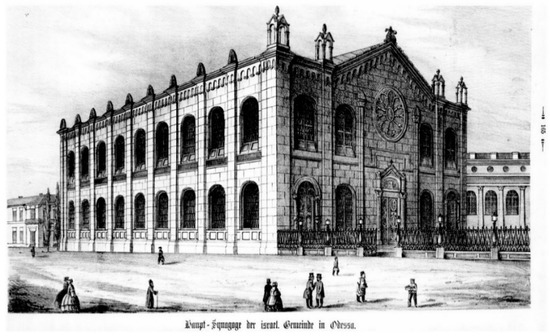

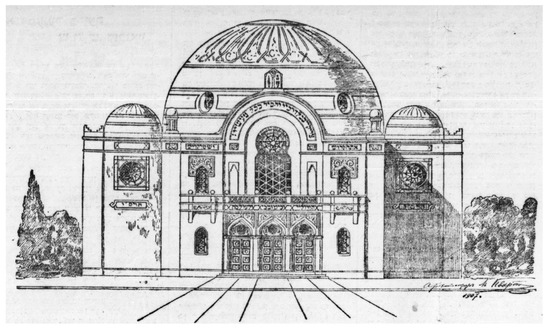

Indeed, the first synagogue in Russia built deliberately as a choral synagogue was the new building of Odessa’s communal Main Synagogue. Its design was prepared in 1847 by the non-Jewish architect Francesco Morandi in the neo-Gothic style.13 The final design approved in St. Petersburg, however, no longer included any Gothic elements (Figure 1)14 and the historian of architecture Sergey Kravtsov has pointed out the similarity of the Main Synagogue’s western façade to the Rundbogen-style synagogue in Kassel (1834–1839), which served as a model for several mid-nineteenth century “modern” synagogues in central and eastern Europe (Kravtsov 2017, pp. 114–16; 2018. See also Hammer-Schenk 1981, pp. 114–23).

Figure 1.

The Main Synagogue in Odessa, arch. Francesco Morandi, 1847–1860 (“Zur Abbildung” 1860, p. 165).

There is, however, a more powerful model for Odessa’s Main Synagogue—the Allerheiligenhofkirche (Court Church of All Saints) in Munich, constructed by the famous architect Leo von Klenze in 1826–1837 (Figure 2). The similarity between the two exteriors is striking: a tripartite entrance façade with a gable; a rose window with a 12-petal rosette around an open center ring, which Klenze took from San Zeno in Verona; a portal imitating San Carlo dei Lombardi in Florence (in Odessa the figures of saints in the rounded tympanum were replaced by the Tablets of the Law); a horizontal molding that extends up and over the portal; two pilasters that end without visually supporting anything (borrowed from the Piacenza Cathedral); a “Lombard” arcade along the cornice; and finally, four turrets atop the façade, which echo the turrets that crown the basilica of San Marco in Venice (Musto 2007, pp. 154–60).

Figure 2.

H. Schönfeld, “Die Allerheiligenkirche in München”, 1838. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:München_Allerheiligenkirche_Soeltl_1838.jpg.

Klenze and his patron, the Bavarian King Ludwig I, understood the medieval architecture of Lombardy as well as the Romanesque architecture along the Rhine as Byzantine, and followed Friedrich Schlegel’s ideas that Byzantium was the embodiment of a special connection between Germany and the East, including original Christianity and ancient Greek heritage (Musto 2007, pp. 36–43). The historian of architecture Jeanne-Marie Musto has demonstrated how Ludwig I, using the same system of coordinates, imposed the Moorish revival style—deliberately non-Christian—on his Jewish subjects. After his personal intervention in the design for the synagogue in Ingenheim, prepared by Friedrich von Gärtner in 1830–1832, all other synagogues in Bavaria were built in the neo-Moorish style (Musto 2007, pp. 357–74).

While the Moorish revival style did not come to Russia until the 1880s, we must ask why the Bavarian court church was used as the model for the Odessa Main Synagogue. The striking difference between Morandi’s initial design and the constructed building shows that the adoption of the Munich example was imposed by the authorities in St. Petersburg, who approved the synagogue design c. 1850.15 Leo von Klenze was well known in the Russian capital, where the building of the New Hermitage Museum was being constructed according to his design in 1842–1852. Most probably, officials went after the contemporary European idea that the Byzantine style, as the style representing the East, was most suitable for synagogues.16 Klenze’s church, for them, represented an authoritative contemporary rendering of this style (later it would be re-interpreted as Rundbogen or Romanesque revival). None of the Jewish descriptions of the synagogue, which are discussed in the next paragraphs, mentions its architectural style or its exterior in general. Therefore, it is possible to conclude that the stylistic choices were made by the Christian architects and officials, while Jewish activists at this early stage did not have enough background to appreciate them and their ideological implications.

The cornerstone of the Main Synagogue was laid in 1850 and on this occasion Alexander Tzederbaum, editor of maskilic newspapers and secretary of the Brody Synagogue in that period, described the planned interior design of the synagogue in detail.17 Tzederbaum’s description enables us to understand which features of the Main Synagogue were novel for Russian Jews and deserved special attention. Tzederbaum mentioned that twelve columns supported the interior women’s gallery on three sides of the prayer hall and dwelled on the description of the “sanctuary” (dvir) in the eastern apse of the building, which included a gilded Torah ark, a table for reading the Torah, a table for the cantor, and sufficient space for the choir. Just as important was the arrangement of the seating: pews with armrests on the chairs would prevent disorderly movement of worshippers, who would now be seated facing the “sanctuary”; in the absence of a central bimah (the podium from which the Torah scrolls are read), an aisle would lead from the entrance directly to the “sanctuary”. The building’s design also included a room for choir rehearsals and another room where the cantor and choristers could change clothes, into their special robes for worship (Tzederbaum 1856; published also in Ahrend 2006).

The Main Synagogue was unveiled ten years later, in 1860 (Polishchuk 2002, p. 27), but in 1858 it already made an impression on a visitor from the north. His text was quite similar to Tzederbaum’s and also emphasized the new features, never seen before. The author mentioned the women’s gallery along three sides of the prayer hall, with a “metal fence almost of human height” (i.e., a mehitzah, the partition that prevents men from seeing women); wooden pews all facing the Torah ark, a central aisle between them; a square, demarcated platform for the cantor and choir; a table for reading the Torah; and a wooden Torah ark decorated with columns and lions (M.E.V.E.N. 1858;18 the use of traditional imagery in modernized synagogues deserves special discussion). The synagogue also impressed the Belgian scholar Gustave de Molinari, who wrote after visiting it on a Friday night: “The new synagogue is the most remarkable monument of Odessa … it is an elegant building, half Byzantine, half Moorish. … Two seven-branched chandeliers illuminate the altar. A tenor dressed in a vestment sings Mendelsohn’s arias with a superb voice” (Molinari 1877, pp. 236–37).

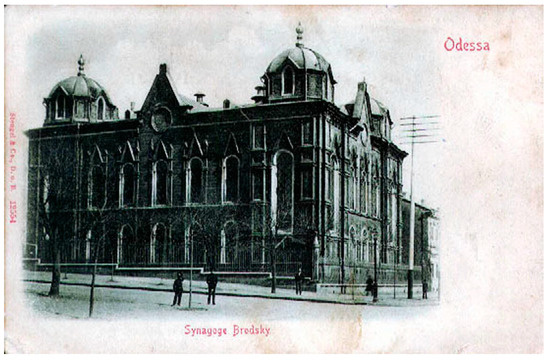

The new Main Synagogue was modelled after the modernized Brody Synagogue, which allowed the Brody congregation to dissolve itself and join the Main Synagogue in mid-1861. However, a conflict between the Main Synagogue worshippers and the Brody newcomers broke out during the High Holidays. The details of the conflict are unclear, but it involved the bimah and issues of honor.19 As a result, the Brody Synagogue was re-established in its former rented premises in May 1862 and the congregants immediately decided to build their own building.20 Its foundations were laid on 18 August 1863 and the new Brody Synagogue was consecrated five years later, on 10 April 1868 (Tzederbaum 1863a, 1863b, 1868a, 1868b). Its design was by a non-Jewish architect, Osip Kolovich, the façades featured neo-Gothic elements, and four small, domed towers adorned the corners of the building (Figure 3).21 While exterior views of the Brody Synagogue were reproduced many times, only two interior photographs are known, from 1910 and 1918 (Hundert 2008, p. 1238; Iljine and Herlihy 2003, p. 71; Gubar’ 2018, p. 272). They show the low wooden structure of the Torah ark, occupying the entire width of the prayer hall, with a dome and turrets, in front of which is the area for the cantor, choir, and Torah reading. At the upper level of the ark, one can discern the large organ that was installed in 1909; a special reconstruction was undertaken for this purpose.22 The ark with the organ and place for the choir above it resembles the arks in many Reform synagogues in central Europe.

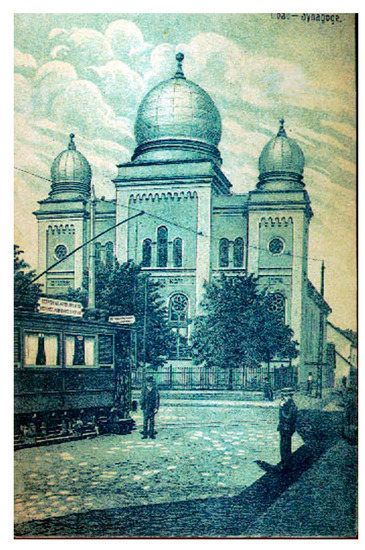

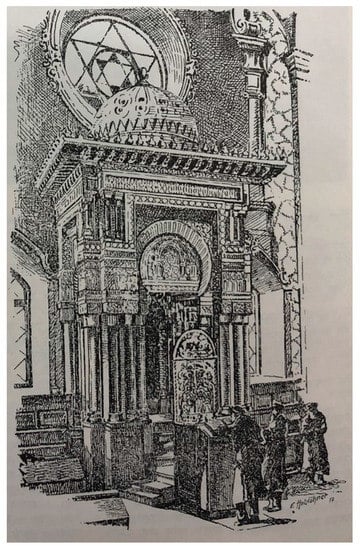

Figure 3.

The Brody synagogue in Odessa, arch. Osip Kolovich, 1863–1868. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

The prominent buildings and impressive choral worship of the Main and Brody Synagogues influenced the Jews of Odessa. The “choral rite”, which included not only a musically proficient cantor accompanied by a choir, but also a new sense of decorum, was adopted by the synagogue at the New Market. For the Passover service in 1866 it “borrowed” several choristers from the Main and Brody Synagogues (Tzederbaum 1866). A choir was also introduced at the same time by the minyan of the Society Ma’avar Yabok, situated at the Old Market (Tzederbaum and Goldenblatt 1866). In 1867, the synagogue of the Bikur Holim Society also introduced a new way of worship, but in contrast to other choral synagogues, the cantor and choir there prayed according to the Hasidic nusah Sepharad (Zagorski 1867; Naomi 1877). The next large synagogue built in Odessa in 1879–1887 at Ekaterininskaia Street was planned in the same manner and became known as “the Third Choral Synagogue” (Polishchuk 2002, pp. 135–36; Subbotin 1890, p. 204).23 Its façade, designed by the Jewish architect Lev Tarnopolskii, was mostly neo-Romanesque in character, but resembled the Brody Synagogue: each window was surmounted by a small gable and flanked by two pilasters, while the pilasters of the ground floor had neo-Gothic finials.24 In 1888, however, Tzederbaum wrote that besides the Main, Brody, and Third Choral Synagogues, the choral rite was practiced only in the Po’alei Emunah Synagogue and in the prayer hall of the Jewish Orphanage (run by philanthropists from the Brody Synagogue) (Tzederbaum 1888).25

The practice of placing of the bimah in front of the Torah ark, as in the Main and Brody Synagogues, also gradually spread to other synagogues in Odessa, but it was rarely discussed in newspapers. In 1901, a newspaper reported a prolonged conflict in one synagogue: the worshippers demanded that the bimah be moved back to the center, while the elders opposed it (Saturn 1901). This case demonstrates that there was a movement in the “opposite” direction (another such case took place in Mitau, see below) and shows that the placement of the bimah and the ark together was widespread. The installation of permanent seats instead of movable shtenders (reading-desks) became another novelty, which was accepted by many synagogues, including the strictly orthodox Great Beit Midrash. The introduction of pews seems to have gone smoothly, since only one conflict about the replacement of shtenders was reported in Jewish newspapers (“Me’shtelt zikh bay der alef” 1870; Tzederbaum 1888).

The influence of the Main and Brody Synagogues was not only felt in the city of Odessa but spread throughout Novorossia—a large area in the south of the empire, with strong economic and cultural ties to Odessa, as well as to other communities in the south. In some cities, maskilim and modernized Jews were able to take over the existing communal synagogues and reshape them in a “modern” fashion. Thus, the Great (or Nikolaevskaia) Synagogue in Kherson, established around 1841,26 was converted into a choral synagogue by its elder, Tuvia Feldzer, as early as 1862, according to the pattern that “he saw in Odessa”. The changes included pews facing the Torah ark and a marble bimah with room for a cantor and choir (Har Bashan 1862; Nevelstein 1863). It seems that the smaller renovations of 1862 culminated in a large-scale reconstruction in 1865: the prayer hall was enlarged, a women’s gallery on iron columns installed “as in Odessa”, and the old “traditional” Torah ark, out of place in the new design, was sold to the Hurvah Synagogue in Jerusalem (Bruk 1865; Polishchuk 2002, p. 144). Similarly, the Great Synagogue of Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipro), built around 1848,27 was “modernized” by its elder Zeev Shtein in 1863: silence during services was established, the cantor and choir behaved “as in Odessa”, and chairs and benches were rearranged to face east.28 The bimah, however, remained in the center of the prayer hall and was moved toward the Torah ark only by the new elders in 1884, notwithstanding the protests of traditionalists.29 In Rostov on Don, a new communal synagogue was built in 1866–1868 in the modern design, i.e., “without a bimah”. No choir is mentioned, but the cantor dressed “as a priest” (Nisht keyn rostover 1869).30 All three synagogues became known as choral synagogues.

In other cities, groups of maskilim founded separate prayer houses with choral worship. In Berdichev (now Berdychiv) in 1866,31 Kharkov (Khar’kiv) in 1867,32 and Nikolaev (Mykolaiv) in 1868 (Vishnevski 1868; Abramovich 1868; Taych 1868), choral synagogues were opened in rented premises, while in Elisavetgrad (Kropyvnytskyi) from the mid-1860s and in Kishinev (Chișinău) from around 1878 they were attached to Talmud Torah schools (modernized education for Jewish children was one of the cornerstones of Haskalah).33 In Kiev (Kyiv), attempts to establish a choral synagogue also began in 1867, but due to the problematic legal status of Kiev Jews they did not bear fruit for a long time. A Choral Prayer House for the High Holidays in rented premises was mentioned there in the 1880s (Meir 2007, pp. 632–33; 2010, pp. 91–97, 170–77; see also “Kiev” 1888a, 1888b). The prestige of the choral rite in the 1870s was such that the communal Old Synagogue in Kherson in 1880, communal synagogues in Kremenchug (now Kremenchuk) in 1880, Nikolaev in 1881, and Elisavetgrad in 1884 also introduced the choral rite, compromising with traditionalists on certain ritual points.34

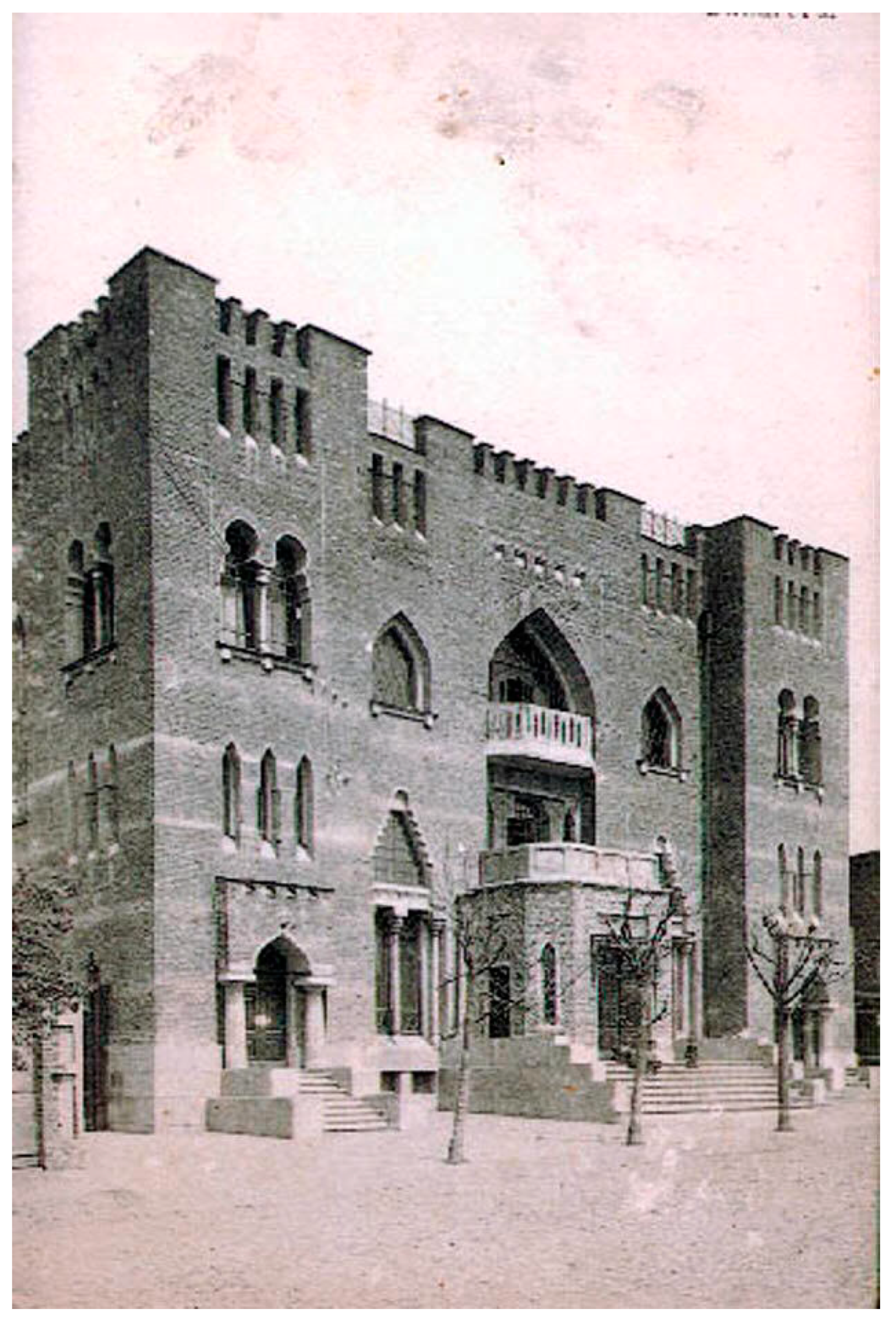

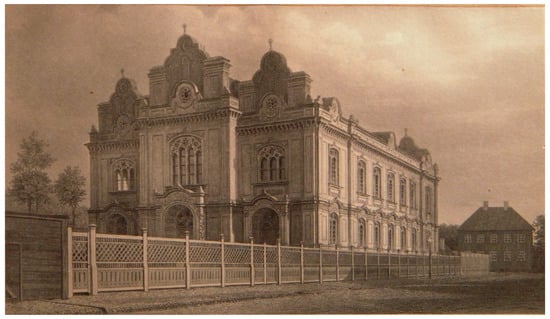

Founding a temporary choral synagogue was only the first step towards building one from scratch, which happened at a different pace. The first purpose-built choral synagogue outside Odessa was the Choral Synagogue in Berdichev, consecrated during the High Holidays of 1868 (Figure 4). It was proudly reported that the new synagogue “can compete with the synagogues in Odessa and abroad” (Hailperin 1868),35 and that its choir was second only to Blumenthal’s choir in Odessa’s Brody Synagogue (Ben David 1892). There are no known photographs of the interior, but a written description states that it was “similar to a Protestant church; columns, rows of pews, [women’s] galleries” (Subbotin 1890, p. 106). The neo-Baroque exterior of the synagogue showed independence from the Odessan models. It also included some elements of Rundbogen style, such as the double window above the main entrance, which alluded to the Tablets of the Law.36 The Choral Synagogue in Nikolaev was erected in 1880–1881 “according to the model of Odessa”, and its façade was in neo-Gothic style, that of the Brody Synagogue (B-skii 1880; Shats 1881, p. 1419; Polishchuk 2002, p. 140).37 In Elisavetgrad, the idea to build a permanent building “modelled after Odessa” was expressed in 1878 (Ben-Shim’i 1878), but a synagogue was erected only in 1895–1897. In Kharkov, the congregation rented a former mansion of the nobility with a prominent cupola, and therefore was in no rush to replace it until the building became dilapidated in 1906 (Kotlyar 2004, p. 49; 2011, p. 44).38 In Kishinev, a choral synagogue was built approximately at the same time, in 1904–1913. These late buildings in Elisavetgrad, Kharkov and Kishinev, all in Oriental style, are discussed below. Lazar Brodsky Choral Synagogue in Kiev, due to the objections of the authorities, was built only in 1897–1898 and its façades featured decoration of Russian-Byzantine and neo-Russian character, as appropriate to the city known as “the mother of Russian cities” and the heir to Byzantium (Figure 5).39

Figure 4.

Choral Synagogue in Berdichev, 1868. Postcard, early 20th century. Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Бердичівська_Велика_хоральна_синагога_19_ст.jpg.

Figure 5.

Lazar Brodsky Synagogue in Kiev, arch. Georgii Schleifer, 1897–1898. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

Although the founders of the Brody Synagogue declared that they modeled their worship after “the best Austrian synagogues” and indeed, their cantors sang in the manner of Solomon Sulzer in Vienna, the architecture of all the buildings discussed above had no counterpart in Vienna nor Budapest, where large Temples in Oriental or neo-Moorish style were erected in the 1850s.40 None of the choral synagogues erected in the south in the 1860s–1880s were built in the neo-Moorish style; this style was introduced in the region only in the 1890s under the influence of the Choral Synagogue of St. Petersburg, as demonstrated below.

2.2. Vilna and the North

The process of the establishment of choral synagogues in the northern, more traditional part of the Pale of Settlement began at the same time as in the south, but its scale was much more modest. Like in Odessa, the first maskilic prayer house in the region appeared in the 1820s, but it was not a public minyan, but the private kloyz of the Katsenelenbogen family in Vilna (now Vilnius)—one among many private kloyzn of the Vilna Jewish elite (Finn 1993, pp. 57–58; Zalkin 1998, pp. 242–43; 2000, pp. 105–7; 2009, pp. 386–87; V. Levin 2012, p. 318).41 In contrast to other Vilna synagogues, the Torah there was read according to “the rules of grammar” and a regular sermon on the weekly Torah portion was given (Finn 1993, p. 57; Zalkin 2000, p. 105). As in Odessa, there was a desire to establish a public synagogue in Vilna in the 1840s. For example, an idea of opening a vocational school for orphans with “a small prayer house according to the model of the Temple in Kassel” was expressed in 1842 (Zalkin 2009, 387n11). Finally, a public maskilic synagogue under the name Taharat Ha-Kodesh (Purity of Holiness) was founded in May 1847. It was located in a rented hall, with a boys’ choir accompanying the service and regular sermons given in Hebrew. The board insisted on order, decorum, and silence during prayer.42

In the same year, 1847, another maskilic prayer hall opened in the state-sponsored Vilna Rabbinic Seminary.43 The seminary teachers gave regular sermons there from 1850, and from 1860 the sermons were given in Russian only (Istoricheskie svedeniia o Vilenskom ravvinskom uchilishche 1873, pp. 9, 26; V. Levin 2012, p. 321). It seems, however, that there was no choral worship in that prayer hall, notwithstanding the fact that the seminary choir participated in official events held in the Great Synagogue of Vilna (Toyber 1861; P.A.P. 1863; Halevi 1865; Tzederbaum 1870a; Istoricheskie svedeniia o Vilenskom ravvinskom uchilishche 1873, p. 41). This fact shows that the use of a choir at synagogue ceremonies in the presence of state officials was considered necessary. After the transformation of the seminary into the Jewish Teachers’ Institute in 1873, the choir only sang the prayer for the well-being of the tsar. Full-scale choral worship, with one of the teachers serving as cantor, was introduced at the institute’s prayer hall only in 1880.44 The Rabbinic Seminary in Zhitomir (now Zhytomyr) established its prayer hall in 1857. In contrast to Vilna, it was situated in rented rooms and not in the seminary building, which allowed greater public access. The sermons there were “often conducted in Russian” (Kravtsov and V. Levin 2017, p. 754).45

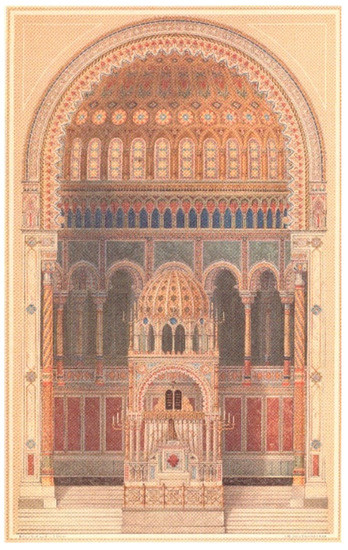

While in the affluent communities in the south, maskilic synagogues were attached to community-run schools, state-sponsored Jewish schools served as a convenient means of organizing choral worship in the north.46 Thus, a maskilic prayer house was opened in 1866 in a “spacious” classroom of the Jewish school in Starokonstantinov (now Starokostiantyniv),47 and the Ohel Yaakov (The Tent of Jacob) Synagogue was founded in the Jewish school in Kovno (now Kaunas) around the same time.48 The Starokonstantinov prayer house did not survive for long. The congregation of Ohel Yaakov, in contrast, was able to lay a cornerstone of its permanent building on 27 June 1872 (Jonathansohn 1872). The synagogue, designed by the Kovno province architect Iustin Golinevich, was consecrated in 1875 (Cohen-Mushlin et al. 2010, vol. 1, pp. 204–6).49 The Ohel Yaakov Synagogue—like the Tłomackie Street Synagogue in Warsaw built in 1872–1878—was modelled after the New Synagogue on Oranienburger Straße in Berlin (1855–1866). Its western entrance façade was dominated by an onion dome and its eastern apse housed the Torah ark preceded by a ciborium, a table for reading the Torah, and the choir gallery.50 The neo-Moorish design of the entire apse (Figure 6) made it a kind of reduced copy of the apse in Berlin (Figure 7), while the façades of the synagogue were neo-Romanesque.

Figure 6.

Torah ark in the Ohel Yaakov Choral Synagogue in Kovno. Photo 2009 by Vitalij Červiakov. “Synagogues in Lithuania: A Catalogue” archives. Published with permission.

Figure 7.

Eduard Knoblauch, Torah ark in the New Synagogue on Oranienburger Straße in Berlin. (Knoblauch and Hollin 1867, Blatt 7).

The example of choral worship in Ohel Yaakov was so attractive that the New Beit Midrash in the city, where “the majority of the elite” prayed, hired a cantor and a choir in 1872 (the cantor was brought from Odessa, where he was a chorister in Blumenthal’s choir in the Brody Synagogue) (Dover emet 1872, p. 150).

Other choral congregations in the north were not so quick to erect permanent buildings. In Zhitomir, the first attempt to build a choral synagogue, in 1888–1889, was unsuccessful, and the synagogue moved into a purchased house only in the early twentieth century. The house had a large prayer hall with a women’s section and a rehearsal room for the choir, where there was a harmonium (Kravtsov and V. Levin 2017, pp. 759–60). The Taharat Ha-Kodesh Synagogue in Vilna changed location several times, but its leaders dreamed of a specially built edifice. A design for a permanent neo-Gothic building with a bimah in front of the ark was prepared in 1877, but it was not implemented. Instead, the synagogue moved into a wing in the courtyard of one of the worshippers, where the bimah stood in the center. From 1886, Taharat Ha-Kodesh was situated in another “narrow” rented house. By 1892 the synagogue already had a harmonium, and from 1894 there were again plans for a permanent building, which was finally founded in April 1902.51

The history of the choral synagogue in Belostok (now Białystok) will serve as a conclusion for our discussion of the northern areas of the Pale of Settlement, because, paradoxically, it combined all the above-mentioned features, but in a sequence that differed from other cities. The synagogue was established by a group of maskilim on rented premises in the late 1860s,52 and in February 1868 it moved to a rented hall in the building of the state-sponsored Jewish school (Frenkel 1868).53 In 1872 or 1874, the synagogue moved to the rebuilt private beit midrash of heirs of the local millionaire, Itche Zabludovsky, which had no distinctive exterior features (Hershberg 1949, vol. 1, pp. 231, 278; cf. also Zabludovsky 1969, pp. 18–20). After a conflict over a cantor, a splinter group established another choral synagogue in Białystok under the name Adat Yeshurun, which subsequently became dominated by Zionists (Hershberg 1949, vol. 1, p. 231; “Mi-bialystok” 1898).54 In 1903, however, representatives of “Zabludovsky’s Choral Synagogue” and “Beit Midrash Adat Yeshurun” decided to build a new choral synagogue together, a decision that was not realized (“Yidishe nayes in rusland” 1903a). The split into two congregations and the attempt to build a common, permanent building prove that there was enough room in the city for two modernized congregations, but not the financial means to erect two—or even one—choral synagogue.

2.3. Riga and Kurland

The Jews of Riga and Kurland are usually seen as especially receptive to Haskalah and German influence. The history of the choral synagogues in the area, however, may correct this view to a certain degree.

In Riga, where the first German Reform rabbis, Max Lilienthal and Abraham Neumann, officiated from the 1840s, Jews did not have property rights and could not purchase a plot for the synagogue until 1850. The Great Synagogue, however, was erected only in 1868–1871, at the time that many other choral synagogues in the empire were built (Figure 8). The synagogue was designed by local German architect Paul Hardenack and was described by contemporaries as “Renaissance style” (W.K. and P.H. 1873, p. 48).55 The synagogue was usually called Great or Choral, but the placement of the bimah remained quite traditional: a description published in 1903 stated that the bimah “for singers, from where the Torah scrolls are also read” was situated in the middle of the hall (Mandelstamm 1903, p. 189). This arrangement was captured in a photograph of 1937.56

Figure 8.

Great Choral Synagogue in Riga. Etching 1873 (W.K. and P.H. 1873, p. 48).

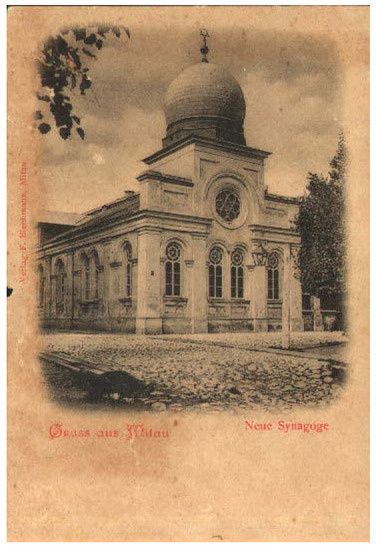

The story of the Choral Synagogue in Mitau (Mitava, now Jelgava) began in the early 1860s with the election of a modern and active crown rabbi, Solomon Pucher. Apparently, under his influence, the local merchant Samuel Friedlieb rebuilt the old Mitau synagogue in 1864, which also became known as the Great Synagogue.57 The new building had a prominent onion dome (Figure 9), reminiscent of the Oranienburger Straße Synagogue,58 and the bimah was situated in front of the Torah ark. Ten years later, the orthodox newspaper Ha-levanon proudly announced that Friedlieb regretted this decision and moved the bimah to the center of the hall; he also promised to direct his children to leave it there for the future (A.B.A.R. 1875).59 It seems, however, that the modern choir continued functioning in the synagogue in the 1880s and 1890s.60

Figure 9.

Great Synagogue in Mitau. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

The Choral Synagogue in Libau (Libava, now Liepāja), erected in 1873 on the site of the old communal synagogue, was also modelled after the Oranienburger Straße Synagogue. Its western side was crowned by three domes (Figure 10). Its construction caused bitter conflict with traditionalists, who appealed against the new synagogue to the Minister of the Interior and the case was transferred to the deliberations of the Rabbinic Commission of 1879.61 The orthodox historiography of the early twentieth century presents another narrative (Ovchinski 1908, pp. 103–4): a Lithuanian rabbi prohibited praying in the new synagogue since its bimah was situated near the Torah ark, the women’s section had a low mehitzah, and the dome was topped by a Star of David (for a discussion of the Star of David see the “External Signage” section below). The synagogue stood empty for three years until other Lithuanian orthodox rabbis intervened and convinced the congregation to move the bimah to the center, to extend the mehitzah upwards, and to remove the Star of David from the domes (indeed, photographs show the cupolas topped by round finials, Figure 10).62

Figure 10.

Choral Synagogue in Libau. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

No other choral synagogues are known in Kurland. Acculturation of the local Jews did not bring with it a desire to modernize synagogue worship.

2.4. St. Petersburg and Moscow

Choral synagogues in the capital cities, St. Petersburg and Moscow, were conceived as model institutions for the representation of Russian Jews in favorable light before the state authorities, which was considered an important step on the path to emancipation. The anticipated importance of both synagogues in the context of Jewish policies of the Russian state made the building process long and painful, and, according to historian Yvonne Kleinmann, the synagogues “became a political problem” even before their construction (Kleinmann 2006a, p. 338).

When the government allowed wealthy Jewish merchants to dwell outside the Pale of Settlement, many affluent Jews came to settle in St. Petersburg and in 1860 they established the Merchants’ Prayer House.63 Although the leadership of the new community was Haskalah-minded and appointed Abraham Neumann from Riga as the city’s rabbi as early as 1863, the decorum of the Merchants’ Prayer House was not without flaws. Neumann wore “foreign rabbinical dress” and preached in German once in a month, but the congregation’s behavior during services was not orderly, especially during his sermons. The bimah, furthermore, was situated in the center of the hall (Kangiser 1864; “Kol mi-St. Peterburg” 1865). Choral worship appeared in St. Petersburg only in 1868, when law student David Feinberg, just returned from a trip to Europe, and a merchant from Berdichev Isaac Wolkenstein established a temporary choral prayer house for the High Holidays. They invited a student of the Imperial Conservatory, Herman Goldstein, as cantor, and composed a choir of 16 singers, dressed “as abroad” (Pogorelski 1868; Mandelkern 1868; Feinberg 1956). This splinter group consisting of the most prominent merchants and bankers succeeded in getting the permission of the emperor for a permanent choral synagogue building in 1869, while the prayer house became the temporary synagogue. The latter existed until the inauguration of the Choral Synagogue in 1893, since the building process was extremely slow. The authorities did not allow the purchase of a suitable plot for the Choral Synagogue for ten years, until 1879, and negotiations about its architectural design continued for another four years.64 The interior design of the initial temporary synagogue is unknown. The only clear detail is that a harmonium was purchased in 1885, under the pretext of teaching choir boys, but the price for “a wedding with organ” was also recorded at the same time.65 In 1886, the temporary synagogue moved to the small hall of the unfinished Choral Synagogue, which had a central bimah and a loft for the choir on its western side.

The modernized Jewish elite in Moscow understood the permission to build a synagogue in St. Petersburg as a sign that they could also establish “contemporary” worship. The Choral Synagogue in Moscow was solemnly inaugurated on 1 July 1870. The prayer hall had women’s galleries on its three sides; the bimah and cathedra for the preacher were together with the Torah ark. The cantor and choir of six children were dressed in black robes and caps with prayer shawls around their necks (“Di eynveyhung fun der moskver shil” 1870; Magidson 1870). In 1879, after the site for the St. Petersburg synagogue was finally purchased, the Moscow congregation also bought an existing edifice, which was converted into a synagogue by the Jewish architect Semion Eibushits in 1886–1891. Like the Tłomackie Street Synagogue in Warsaw, it had a neo-Classical façade and a dome, which was removed in 1888 on the demand of the Russian Orthodox Church. Nonetheless, the authorities prohibited the opening of the synagogue and it could not be used until the first Russian revolution of 1905–1907.66 The consecration of the synagogue, renovated by architect Roman Klein, took place on 23 August 1907 (“Moskva” 1907a, 1907b): the Torah ark, cathedra for the rabbi, and the bimah were situated in the eastern apse, which apparently had been planned in 1886 (Figure 11).67 An organ (probably a harmonium) in the synagogue was not played on Saturdays, but used during weddings (Shva-na 1911).

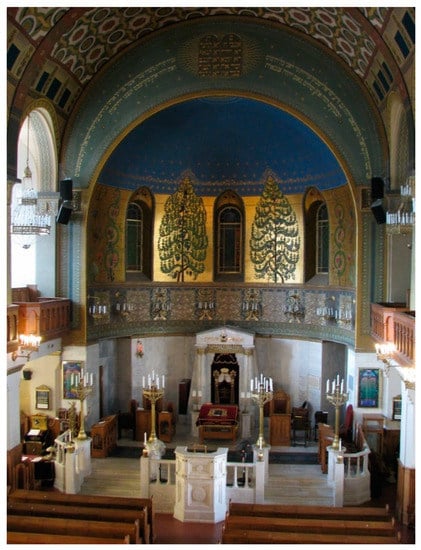

Figure 11.

Apse of the Choral Synagogue in Moscow, arch. Roman Klein, 1907. Photo 2013 by Vladimir Levin.

In St. Petersburg, from the very beginning it was clear that the Oranienburger Straße Synagogue was the inspiration for the future building.68 The Jewish artist Lev Bakhman and his Russian colleague Ivan Shaposhnikov designed the synagogue in 1879 in the neo-Moorish style with a dome towering above the western façade (Figure 12). The building was erected in 1883–1893 with an altered design by Aleksei Malov, but its eastern apse was strikingly similar to the apse in Berlin, with the ciborium in front of the Torah ark and the upper choir gallery (Figure 7 and Figure 13). In its final form, the choir gallery in the apse was not very functional, and therefore a special choir balcony on the western wall above the women’s gallery was installed.69 A harmonium still stood on that balcony at the very end of the twentieth century (e.g., Beizer 2000, p. 205).

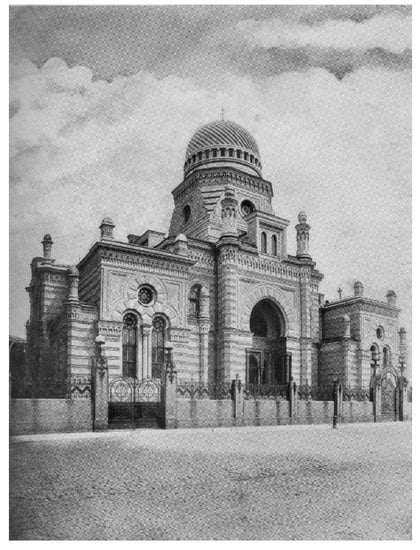

Figure 12.

Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg arch. Lev Bakhman and Ivan Shaposhnikov, 1879–1893. Photo 1912 (Harkavi and Katsenelson 1912, p. 944).

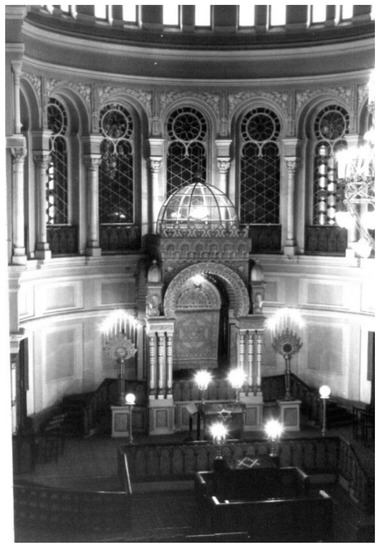

Figure 13.

Torah ark and ciborium in the eastern apse of the Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg. Photo 1992 by Zev Radovan. Center for Jewish Art.

Although all the designs for the St. Petersburg synagogue placed the table for Torah reading in the eastern apse, in the end, the bimah was built as a separate wooden structure. The Board of the Choral Synagogue agreed in 1892 that it would be situated in the center of the prayer hall and in a newspaper this decision was explained as “the wishes of the orthodox”.70 This design, however, did not satisfy the congregation. In 1896, it was decided that persons reading the Torah would face the hall, not the Torah ark,71 and a final resolution to move the bimah near the ark was made in 1906.72 There it stood until the renovation of the synagogue in 2000–2005, when it was placed in the middle of the hall.

2.5. After St. Petersburg

The construction of the Choral Synagogue in St. Petersburg could be considered a turning point in the history of synagogue architecture in Russia, and especially in the history of the choral synagogues. The synagogue became well known both to professional architects through the publication of its designs in 1881 and again in 1902 (“Proekt sinagogi dlia S.-Peterburga” 1881; Baranovskii 1902, vol. 1, p. 402) and to the general public. Its inauguration on 8 December 1893 was widely reported by the press and some of the most popular Russian magazines, Niva and Vsemirnaia illustratsiia, published depictions of the synagogue. Images of its exterior were often printed on postcards.73

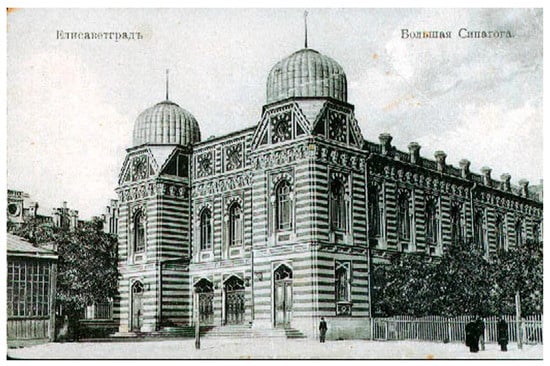

Some elements of the St. Petersburg synagogue’s exterior, such as the large central horseshoe and slightly pointed arch topped by the Tablets of the Law, and the round windows in square frames, had already been used in 1883 in the design of Lazar Poliakov’s private synagogue in Moscow, prepared by Mikhail Chichagov (Stolovitskii and Gomberg 2015, p. 16). The most unique feature of the synagogue’s exterior, however, was the dome drum, inspired by the cupolas of the fifteenth-century Mamluk mausoleums in Cairo (Wischnitzer 1964, p. 209). The Cairo-inspired dome, combined with the central horseshoe pointed arch topped by the Tablets of the Law and the hexagonal windows, appeared in 1892 in the design of the Great Synagogue in Lida by Vilna province’s architect, Aleksei Polozov.74 Although the actual dome in Lida was built differently, its façades resembled the St. Petersburg synagogue stylistically. The Torah ark was situated in a ciborium, similar to those in St. Petersburg and in Vilna (Figure 14, cf. Figures 13 and 17).75 The Jewish architect Alexander Lishnevskii used similar design elements in the Choral Synagogue in Elisavetgrad in 1895–1897: two front domes were designed as in St. Petersburg, horseshoe but slightly pointed windows were placed on the second floor, and vertically elongated pentagonal windows were placed on the ground floor (Figure 15).76

Figure 14.

Torah ark in the Great Synagogue in Lida. Drawing by E. Holzlöhner, 1917 (Manor et al. 1970, p. 27).

Figure 15.

Choral Synagogue in Elisavetgrad, architect Alexander Lishnevskii, 1895–1897. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

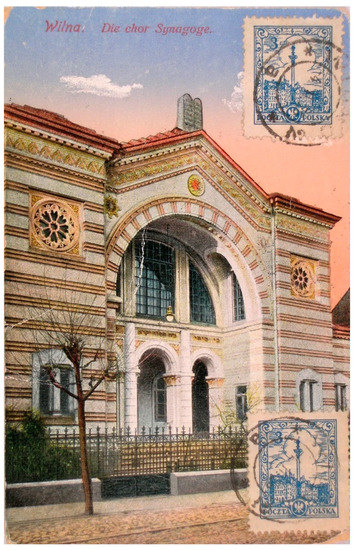

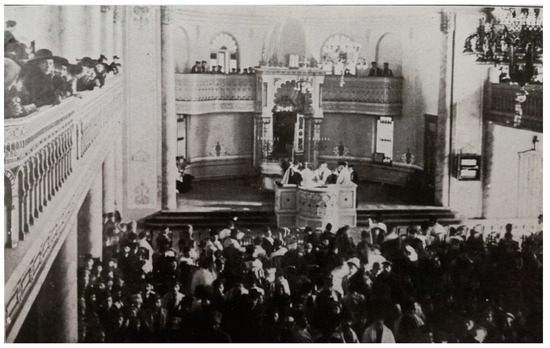

The Great Synagogue in Lida was a traditional synagogue, but the Choral Synagogue in Elisavetgrad was the first in a series of choral synagogues constructed in large provincial cities of the Russian Empire in the neo-Moorish style.77 The neo-Moorish Taharat Ha-Kodesh Choral Synagogue was built in Vilna in 1902–1903 by Jewish architect Daniel Rosenhauz. Although its huge entrance arch is different from that of St. Petersburg (Figure 16), the interior shows the combined influence of Berlin’s Oranienburger Straße and St. Petersburg’s Choral Synagogues (Figure 17). The Torah ark is situated in an apse with two rows of arches and is preceded by a ciborium. The only known pre-war photograph of the interior shows that there was no central bimah (Figure 17), and the most ornamented part of the synagogue still today is a cathedra for the cantor and preacher (Figure 18).78 The Choral Synagogue in Minsk, which started as a minyan of intelligentsia in the Jewish vocational school (Levinson 1975, p. 113), was built in 1902–1906 also in the new Moorish style (“Yidishe nayes in rusland” 1903b; Levinson 1975, pp. 113–14). It had a large horseshoe arch on the exterior (Figure 19) and an apse with a balcony for the choir in the interior (Figure 20). Instead of a ciborium, however, there was a protruding aedicule; the cathedra for the cantor and preacher was very prominent.79 The neo-Moorish Choral Synagogue in Kishinev was erected in 1904–1913 (“A shul fir kishinev” 1904; Shpitalnik 1995, p. 6), with a large arch facing the street and a dome above it,80 and an unrealized design for a choral synagogue in Belostok, by Jewish architect Mikhail Kvart from St. Petersburg, was made in 1907, also in the neo-Moorish style (Figure 21).

Figure 16.

Taharat Ha-Kodesh Choral Synagogue in Vilna, architect Daniel Rosenhauz, 1902–1903. Postcard, 1915–1918. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

Figure 17.

Interior view of the Taharat Ha-Kodesh Choral Synagogue in Vilna, architect Daniel Rosenhauz, 1902–1903. Postcard, 1915–1918. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

Figure 18.

Cathedra in the Taharat Ha-Kodesh Choral Synagogue in Vilna. Photo 2007 by Vladimir Levin.

Figure 19.

Choral Synagogue in Minsk, 1902–1906. Postcard, after 1926. Courtesy of Mordechai Reichinstein.

Figure 20.

Interior of the Choral Synagogue in Minsk, 1902–1906. Postcard, 1918. Courtesy of Mordechai Reichinstein.

Figure 21.

Mikhail Kvart, a design for the Choral Synagogue in Belostok, 1907. (“Der proyekt fun der khor-shul in bialystok” 1907).

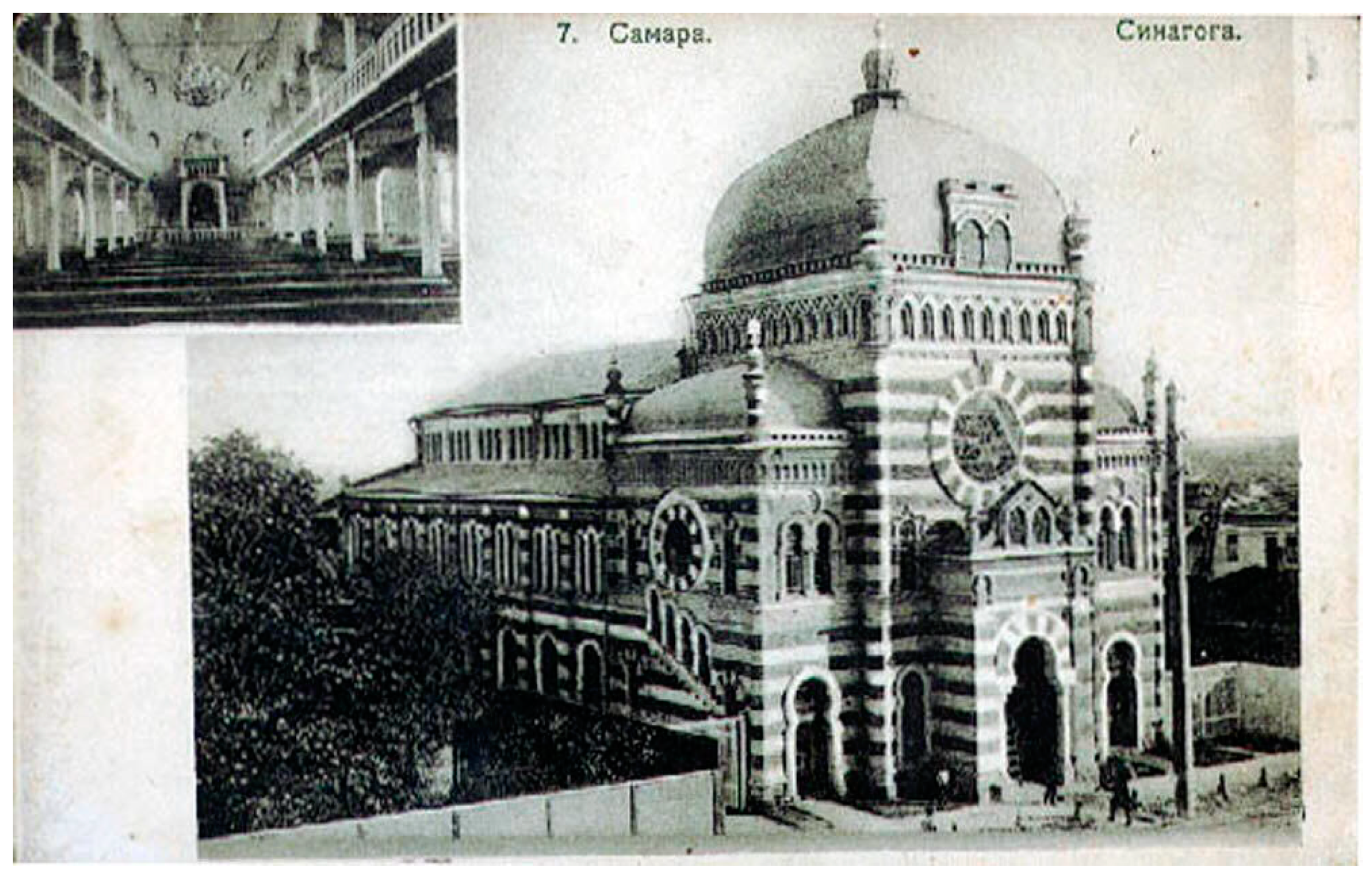

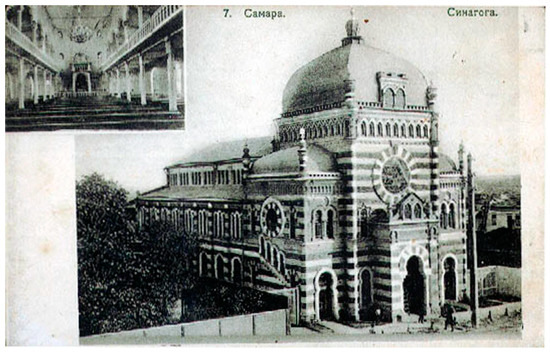

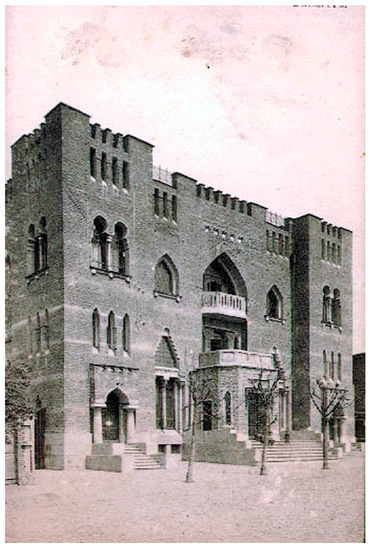

The neo-Moorish fashion spread to areas outside the Pale of Settlement as well. A neo-Moorish synagogue was built in Samara in 1903–1908 by the Jewish architect Zelman Kleinerman. It also had an eastern apse with a protruding aedicule for the Torah ark (Figure 22). The new Choral Synagogue in Kharkov, designed by St. Petersburg Jewish architect Yakov Gevirts in 1909, was much more “modern” than the nineteenth-century neo-Moorish-style buildings, but nonetheless it had Orientalist character. As in the St. Petersburg synagogue, it had an eastern apse with a choir gallery.81 The synagogue in Smolensk was built by city architect, Nikolai Zaputriaev, in 1909–1914. It was Oriental in style with three domes, which the authorities ordered removed, as in Moscow in 1888 (Figure 23).82

Figure 22.

Choral Synagogue in Samara, arch. Zelman Kleinerman, 1903–1908. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

Figure 23.

Synagogue in Smolensk, arch. Nikolai Zaputriaev, 1909–1914. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

The influence of St. Petersburg spread to Siberia as well.83 The wooden Old Synagogue in Omsk was rebuilt in 1898 with neo-Moorish elements on the façades (Yebamah 1900). Even more illuminating is the story of the New Synagogue in that city. The original wooden synagogue was built in 1874 and its exterior was modelled on the Leopolstädter Temple in Vienna. In 1895, the synagogue was damaged by fire and subsequently renovated (Krasnik 1895; Lebedeva 2000, pp. 112–15). Its new look included a dome and neo-Moorish turrets, seemingly influenced by St. Petersburg Choral Synagogue.84 The description of the unveiling of the Stone Synagogue in Tomsk in 1902 stated that “its design resembles the newly built St. Petersburg Choral Synagogue” (“Torzhestvennoe osviashchenie khoral’noi sinagogi” 1902), and an elder of the Tomsk Soldiers’ Synagogue stated that it was restored after the fire in 1907 “in neo-Moorish style” (Tsam 1909, p. 12). The architects of the huge synagogue in Chita in 1907 simply copied parts of a competition design prepared for St. Petersburg in 1879 (Figure 24).85 Photographs of the interiors of the synagogues in Irkutsk and Kabansk show that the table for reading the Torah was situated on the platform in front of the Torah ark.86

Figure 24.

Synagogue in Chita, arch. Ia. Rodiukov and G. Nikitin, 1907–8. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

3. External Signage of Choral Synagogues in the Russian Empire

One of the purposes of the choral synagogues was to demonstrate dignified Jewish worship to non-Jews, and therefore all choral synagogues were built as prominent buildings facing the street and open to all. Easy recognition of the building as the synagogue was an important feature, and there were two major ways of marking the buildings as a synagogue: architectural style and religious symbols.

The neo-Moorish or Oriental style was considered the “Jewish style”, which clearly designated the building as belonging to Jews.87. However, it was never the only style for synagogue buildings. Even in the period of the highest popularity of Moorish revival in Russia—the 1890s–1900s—choral synagogues were built in other styles as well, for example, the Lazar Brodsky Synagogue in Kiev in 1897–1898 with Byzantine and Russian elements (Figure 5), the Choral Synagogue in Baku in 1902–1910 in neo-Greek style (Figure 25), or the Choral Synagogue in Feodosia in 1904–1905 with neo-Romanesque details (Figure 26).88 Thus, like in the rest of Europe, the style was a powerful but not universal method for representing Jewishness and it could reflect a variety of identifications, from clearly Jewish (neo-Moorish) to patriotically local (neo-Russian) to pan-European (neo-Greek and Romanesque).

Figure 25.

Choral Synagogue in Baku, 1902–1910. Photo 2012 by Vladimir Levin.

Figure 26.

Choral Synagogue in Feodosia, 1904–1905. Postcard, early 20th century. Courtesy of the Gross Family Collection, Tel Aviv.

There were two other signs that served to designate the buildings as Jewish: the six-pointed Star of David and the Tablets of the Law with the Decalogue. The 1847 design for the first choral synagogue in Russia, Odessa’s Main Synagogue, included Magen David shaped window bars in the oculi of the eastern and western façades.89 The completed building, at least according to an etching published in 1860, had no Stars of David, but it did have the Tablets of the Law above the entrance door. Two pilasters on its western façade, ending with acroteria, borrowed by Klenze for his Allerheiligenhofkirche from the Piacenza Cathedral—could be understood as alluding to the Jachin and Boaz pillars in the Jerusalem Temple (Figure 1). The Brody Synagogue of 1863–1868 had the Tablets of the Law crowning the gables in the center of all its façades (Figure 3). The placement of the Tablets at the most prominent places of the exterior and interior became, by that time, quite common in central Europe,90 but it seems that there were people in Odessa who criticized the congregation for such extensive usage of the Tablets (Tzederbaum 1870b, p. 281). Since then, the Tablets of Law appeared in many synagogues in Russia. In some places, the presentation of the Tablets of the Law could be considered a sign of religious Reform. For example, Chaim Tchernowitz claimed in his memoirs, without any explanation, that the orthodox rabbi of Kovno, Isaac Elhanan Spector, objected to the depiction of the Tablets above the entrance of the Ohel Yaakov Synagogue (Tchernowitz 1954, p. 160). Elsewhere, the Tablets were proudly displayed as a sign of Judaism without any protests.

The use of the Star of David was even more ambiguous. On the one hand, it is reported that orthodox rabbis strongly objected to the placement of the Magen David on synagogue domes in Mitau and Libau (Ovchinski 1908, pp. 103–4, 112–13). On the other hand, maskilim also opposed its placement on the domes (e.g., “Zikhronot shnat 5623” 1863; Natansohn 1878). Both sides correctly stressed that a Magen David on the domes of a synagogue imitates the cross on churches, and that this practice came to Russia from Germany. One of the most influential opponents of the Star of David was maskil and poet Judah Leib Gordon. In 1879, he described the Magen David as a non-Jewish sign adopted by kabbalists, which has no meaning in Judaism and essentially is a “religious error”. He was ready to reconcile himself with the Stars of David on the mantles of Torah scrolls and on Torah ark curtains as a widespread superstition, but categorically protested its placement on synagogue domes (Gordon 1879, pp. 190–91). The opinion of Gordon, who was then the secretary of the St. Petersburg Jewish community, probably had influence, and the Choral Synagogue in the capital had no Stars of David on its cupola (Figure 12). Other choral synagogues mentioned in the publications of the 1870s, however, were topped by a Magen David: Riga, Mitau, Libau (for a short time), and also the Tłomackie Street Synagogue in Warsaw. In the 1880s and 1890s, the Star of David had already become an unquestioned symbol of Judaism and was depicted on the exteriors and interiors of choral and traditional synagogues.91

4. Features of Reform Synagogues in Comparison to Choral Synagogues

In order to discuss the relationship between choral synagogues in the Russian Empire and the Reform movement, it is necessary to define the features that characterized Reform synagogues in central Europe, which served as models for the synagogues in Russia. The absolute majority of Russian Jews never travelled to Europe, but members of Jewish elite made regular voyages abroad for business, vacation, or medical treatment and could experience worship in Reform synagogues. In addition, the Jewish press constantly published information about various reforms in Europe and its readers were acutely aware of the developments there.

The following twelve features of Reform synagogues in central Europe have been deduced from Michael Meyer’s research, A History of the Reform Movement in Judaism. Almost all these features were mentioned already at the very beginning of the nineteenth century, but they were implemented in various combinations and at a different pace: some were considered “moderate”, while others were characterized as “radical” Reform. These features are:

- Insistence on decorum and order during worship;

- Participation of a male choir in Saturday and holiday prayer service;

- Regular sermons in the vernacular language;

- Confirmation ceremony for girls;

- Wedding in the synagogue rather than in its courtyard;

- Alteration of the prayer book;

- Removal of the bimah from the center of the prayer hall toward the Torah ark;

- Absence of a mehitzah, which prevents men from seeing women in the synagogue;

- Installation of an organ/harmonium;

- Introduction of mixed male and female choir;

- Mixed seating of men and women;

- Celebrating the main worship on Sunday instead of Saturday.

We will begin the analysis of this list from the last three points, which characterized the more “radical” Reform in Europe. None of these three points required any special architectural design and theoretically could be introduced in every synagogue. Mixed seating of men and women did not exist anywhere in the Russian Empire, which was not surprising since it was not common in European synagogues. Separation of sexes was thrown aside only by the Reform movement in the United States.92 Celebration on Sundays was also not very common in Europe. In Russia, the only known attempt to establish congregational prayer on Sundays was undertaken in St. Petersburg in 1909 by Naum (Nehemia) Pereferkovich. However, his initiative did not succeed and he was ostracized by the Board of the Choral Synagogue.93 The mixed choir of male and female voices, which was also not very popular in Europe, was apparently introduced for the first time in Russia in the synagogue of the Society of Jewish Shop Attendants in Odessa in 1902 (Ish Yehudi 1902; Polishchuk 1999, pp. 16–17; 2002, pp. 136–38).94 The attempt of some leaders of the Brody Synagogue in Odessa to introduce a mixed choir around 1909 was unsuccessful, and such a choir appeared there only after the collapse of the tsarist regime, in 1917/18.95 A similar attempt in the Choral Synagogue of St. Petersburg (then Petrograd) in 1921—also a consequence of the revolution and the feeling of liberty—was prevented by the aged orthodox rabbi David Tevel Katsenelenbogen (Beizer 1999, pp. 192–93; 2000, p. 203).

Three other features—numbers 4, 5, and 6—also did not require special architectural arrangements. Confirmation for girls was introduced in Riga in 1840 by Max Lilienthal, a German Reform rabbi invited by the Russian government (Meyer 1985, p. 72) and it was institutionalized in several other communities in the decades that followed.96 It seems, however, that confirmation ceremonies did not become very popular in Russia. As historian Tobias Grill has correctly noted, confirmation was borrowed from Protestantism and therefore “had to seem alien” in the Russian Orthodox or Roman Catholic milieu (Grill 2003, pp. 203–4). Wedding ceremonies inside the synagogues—as opposed to the custom of having them in the synagogue courtyards under the open sky—were introduced with the appearance of choral synagogues and it seems that opposition to this novelty from traditionalists could be negotiated.97 As for alterations of the liturgy, such as exclusions of liturgical hymns and certain prayers and the introduction of prayers in the vernacular, the whole issue still requires special research.98 It seems that the majority of choral synagogues in Russia continued with the traditional prayer in nusah Ashkenaz,99 but there are also indications that prayer books from central Europe were used in the 1860s and 1870s.100 The prayer for the well-being of the tsar, Ha-noten teshu’a le-melakhim, was sometimes translated into Russian for the sake of state officials present in the synagogue, but it was the only part of the liturgy in the vernacular and it was not limited to choral synagogues.101

A discussion of the space and architecture of choral synagogues must therefore be centered on the following six features. Usually, the insistence on decorum, participation of a choir, and regular sermons are mentioned together (Nos. 1, 2, and 3 on our list). The founders of the choral synagogues despised the lack of order in the traditional ones, where talking, moving around the hall during the service, loud personal prayers, congregational responses to the prayer leader, as well as spitting on the floor were common. Many of the founders hoped that the installation of pews facing the Torah ark would reduce the disorderliness, while beadles would control worshippers’ behavior and seating. Some synagogues also insisted on a dress code for worshippers, which significantly contributed to improved decorum (the Brody Synagogue in Odessa and the Tłomackie Street Synagogue in Warsaw).

The participation of a choir in all Saturday and holiday services (No. 2 on the list) meant that it was necessary to provide a large enough space for ten to twenty people in front of the Torah ark. The choral accompaniment for the cantor, however, was not uniquely a feature of choral synagogues; many traditional cantors had boys’ choirs assisting them, especially in the communal Great Synagogues during the High Holidays (in such cases, the cantor and choir stood on the bimah since there was usually not enough room in front of the ark). The distinction of the “modern” cantor (tagged khor-hazan) from the “traditional” one was his musical education and the type of music he performed,102 as well as his special dress: a long black robe (sometimes called an Ornat—vestment in German), a round cap, and a small silk prayer shawl around the neck. The distinction of the choir in a choral synagogue from the traditional choir was also the musical knowledge of the singers and their uniformity of dress (e.g., Zagorski 1870; “Di eynveyhung fun der moskver shil” 1870; Ben-Shim’i 1878; Avner 1884). Traditional choirs usually included only boys, but there are sources that mention adult voices as well.103 In the choral synagogue choirs, adult male voices (tenor and bass) were universally employed.104 Thus, in choral synagogues it was not the use of a choir itself but the dress and the character of the singing that mattered, as well as the behavior of the worshippers. The active participation of the traditional synagogue was replaced by passive listening. In the words of the famous cantor Pinhas Minkowski, “the congregation was impressed not by the pleasant singing of choral cantors but by the splendor of order” (Minkowski 1918, p. 100).105 The traditionalist opposition to the choral synagogues derived partly from this passivity dictated by decorum, when the choir took over the congregational responses, like amen, thus distorting the meaning of public prayer (“Kremenchug” 1880; Avner 1884).106

Ideally, sermons (no. 3 on the list above) were supposed to be delivered from a cancel or cathedra that enables worshippers to hear and see the preacher. However, the cathedra was not an obligatory element in choral synagogues and preachers used to speak from the podium in front of the Torah ark or from the bimah. The first regular sermons in the Russian Empire were introduced in Riga in 1840 by Lilienthal (Meyer 1985, pp. 71–72), and later, sermons were given by other “modern” rabbis who came from Germany: Abraham Neumann in Riga and St. Petersburg, and Simon Schwabacher in Odessa. They all preached in German, and only the new generation of Russian-born crown rabbis began giving sermons in Russian.107

Moving the bimah from the center of the prayer hall towards the Torah ark (No. 7 on our list) was the most prominent change in the interior design of the choral synagogues. Many contemporary descriptions said that “there is no bimah in the synagogue”, meaning that the table for the reading of Torah scrolls stood in front of the Torah ark (e.g., Plungian 1868; I.B. 1880, p. 162; Vites 1891b). The unification of the bimah with the ark created a space with only one focal point. This change was not simply an imitation of Protestant churches; it fundamentally reordered the hierarchical relationship between the congregation and the persons leading the service and restricted the participation of congregants in the service. The singing of prayers, reading of the Torah, and preaching were conducted by “specialists” in one special place, so that the worshippers became passive and disciplined. They were supposed to sit silently in their seats, watching and listening. This change was the main aspect that separated the choral synagogue from the traditional one. According to the traditionalists, the placement of the bimah near the ark contradicted the gloss by Moses Isserles to Shulhan Arukh: “And make the bimah in the middle of the synagogue, so that [the person] who reads the Torah stands there and all will hear” (Orah Haim, 150:5) and violated the halakhic ruling by Moses Sofer (Hatam Sofer), who insisted that the bimah be placed in the center (Sofer 1958, No. 28).108 However, the central bimah is characteristic only in Ashkenazi synagogues, while in Sephardi and Italian congregations the podium for the Torah reading is placed at the edge of the prayer hall, opposite the ark.

The absence of a mehitzah (partition) between the men’s prayer hall and women’s section (No. 8 on our list)—like other issues involving women—attracted much less attention in contemporary texts, though it was as novel as the moving of the bimah. Women’s sections in the traditional eastern European synagogues were situated in separate, adjacent rooms connected to the prayer hall by small openings, which prevented men from seeing women. A women’s gallery inside the prayer hall appeared in Eastern Europe only in the mid-nineteenth century as part of a western architectural pattern implemented initially in the choral synagogues.109 Since the interior gallery significantly improved the visibility of women, special means had to be employed to prevent it, like a high lattice or a curtain.110 As it seems, many choral synagogues did not install such devices.111 Thus, the presence of women in the prayer hall, although they sat separately in the gallery, also became a characteristic feature of choral worship.112

The installation of an organ or harmonium in the synagogue (No. 9 on our list) became, according to Meyer, “the ‘shibboleth’ dividing Orthodox from Reform” (Meyer 1995, p. 184).113 The organ came to the Tsarist Empire relatively late. In 1876, the orthodox newspaper Ha-levanon could still criticize a merchant from Vilna for his intention “to bring an organ from abroad” to be the first organ in a Russian synagogue (“Vilna” 1876).114 When German Reform synagogues installed organs, they were clearly imitating their Catholic and Protestant neighbors. Russian Orthodox churches, in contrast, do not have organs, only choral singing. However, in the largest part of the Pale of Jewish Settlement, the majority of the nobles were Catholics, and Catholicism retained its prestige at the local level, even when it was persecuted by the Russian state.115 Thus, in theory, the installation of organs in synagogues by Russian Jews could be due to the influence of their Catholic neighbors, but it seems more plausible that they were imitating their coreligionists abroad (the question of whether eastern European Jews ever entered Catholic churches deserves a separate discussion).

There were three cases when the organ could be used in the synagogue. First, the organ could be played during wedding ceremonies. Such attempts were made with a rented organ in Odessa’s Brody Synagogue as early as the 1850s, but these attempts were unsuccessful (Tzederbaum 1870b). The synagogue apparently bought a harmonium in 1869 and a wedding accompanied on the organ (harmonium) was reported there in 1870 (Tzederbaum 1870b, 280; Kelner 1993, p. 141). Toward the end of the century, wedding ceremonies with the organ became common in other choral synagogues.

The second use of the organ was to play it on weekdays, when Halakhah does not prohibit Jews from playing musical instruments. Such practices were reported in the same Brody Synagogue, at Hanukkah and Purim services, as well on other occasions, like the festivities for the centennial of Moses Montefiore in 1884 (Kelner 1993, p. 141).116 In 1892, a harmonium was played during the memorial service for Judah Leib Gordon in the Taharat Ha-Kodesh Choral Synagogue in Vilna (“Vil’na” 1892; Cohen-Mushlin et al. 2012, vol. 2, p. 256) and in 1914 the harmonium accompanied the festive service in honor of the empress Alexandra Feodorovna in the Soldiers’ Choral Synagogue in Rostov on Don (The YIVO Archives, RG 212, folder 32, fol. 17v).

The third use of the organ was during Saturday and holiday prayer services, played by a non-Jew or a Jew (violating Halakhah). Saturday prayer with organ accompaniment did not become prevalent in Russia. Thus, rumors in 1895 that an organ would be played in the Brody Synagogue on Saturdays and holidays were immediately refuted by its elders (Ben-Avraham 1895; Lilienblum 1895; cf. also Abelson 1895). The first pipe organ in a Russian synagogue was installed in the hall of the aforementioned Society of Shop Attendants in Odessa in August 1902.117 The organ was produced by the Steinmeyer Company in Oettingen. The liaison between the Society and Steinmeyer was made by the organist of the German Reform church in Odessa, Rudolf Helm, who also hosted the Board of the Society in his church and demonstrated his organ for them. The commission that approved the correct installation of the new organ included, besides Helm, the organist of the local Catholic Church, the conductor of the Odessa Opera, and the choir conductor of the Brody Synagogue, David Nowakowsky (Seip 2008, pp. 284–88). The first service with organ took place during the High Holidays of 1902, together with a mixed choir. This act brought about a prohibition by Odessa rabbis and protests in the Jewish press (Ish Yehudi 1902; Polishchuk 1999, pp. 16–17; 2002, pp. 136–38). The organ, however, continued to be played in this synagogue, as proven by another prohibition issued in 1907 (“Provints” 1907; “Odesa” 1907).118 The participation of Nowakowsky in the commission of the organ in 1902 bore fruit and quite soon after, in 1909, prayer with pipe organ began in the Brody Synagogue as well; the organist was a non-Jew from Sweden named Gelfelfinger. An attempt by traditionalists to bring this issue to the attention of the Rabbinic Commission of 1910 in St. Petersburg was skillfully downplayed by the elders of the synagogue.119

Thus, the most radical alterations of Jewish worship never came to the Russian Empire or else appeared only minimally. The majority of the changes introduced in choral synagogues were of aesthetic nature: they concerned decorum, not the religious meaning or essence of the prayer service. The initial wave of the establishment of choral synagogues by maskilim and modernized Jews became a catalyst for adoption of the choral rite by other groups. Eventually, the choral synagogue became the synagogue of the modernized elite, devoid of special religious significance.

5. Conclusions

The first synagogues with choral worship, regular sermons, and decorum, which opened during the 1840s, were followed by a wave of choral synagogues founded in the 1860s. All of them aspired to build impressive edifices, a process that did not always go smoothly, e.g., the construction of the Main Synagogue in Odessa took thirteen years (1847–1860). Only five choral synagogues were erected in the 1860s (the Brody Synagogue in Odessa, Mitau, Rostov, Berdichev, and Riga) and four more began construction in the 1870s (Kovno, Libau, St. Petersburg, and the Third Choral in Odessa).

More choral synagogues were established and built in the 1880s, 1890s, and 1900s, even in mid-size towns. For example, a Choral Synagogue in Bobruisk on rented premises was mentioned in 1890 (Ben-Adam 1890), a temporary “prayer house of the enlightened” in Gomel was criticized for selling entrance tickets on Saturdays in 1892 (Fridmann 1892),120 and a “synagogue of the enlightened” in Proskurov (now Khmelnytskyi) existed in 1900.121 The spread of choral worship in the south was especially impressive: for example, two out of the four synagogues in Aleksandrovsk (now Zaporizhzhia) were called “choral” in the list of 1911 (Orlianskii 1997, vol. 1, p. 26).122 At the same time, many communal Great Synagogues underwent change and began to employ, on a regular basis, a cantor with a choir dressed as in the established choral synagogues. For example, the Great Synagogue in Rovno (now Rivne), built according to the traditional “nine-bay” layout but finished in the early 1880s, had a space for the choir demarcated by a low fence in front of the Torah ark, while its bimah remained in the center of the hall. It was known for its outstanding cantors and a large choir (Kravtsov and V. Levin 2017, pp. 586, 614 and fig. 35).123 Even the music in the Great Synagogues changed. According to musicologist Sholom Kalib, “the distinctions separating the chor shul from the mainstream large synagogue gradually tended to narrow, and increasingly became irrelevant” (Kalib 2002, vol. 1, part 1, p. 91).

The choral synagogue was, in essence, not necessarily a synagogue where a choir participated in the service. A choir made up of singers with basic musical education and dressed in uniform was only a part of the overall decorum, which included sitting on pews facing the Torah ark, silence and order during the service, a dress code, a musically educated cantor, and regular sermons in the vernacular (or in Hebrew). When there was no choir for some reason,124 decorum and sermons sufficed to define the synagogue as “progressive” by its adherents and “heretic” by its traditionalist opponents. On the other hand, the presence of a uniformly dressed choir in the synagogue in the early twentieth century, did not alone render it choral.

The introduction of choir singing, order, and sermons influenced the interior space of the synagogues. The choir needed a space, usually near the Torah ark, and therefore large platforms or special galleries and lofts had to be built. The preacher also needed a cathedra in a place where everybody could hear and see him. Therefore, many choral synagogues, like Vilna, Moscow, and Minsk (but not Odessa and St. Petersburg), had very prominent cathedrae.125 Since cantorial singing attained great significance, the cantor also used the same cathedra, but faced the Torah ark, not the worshippers.126

The distinctive feature of the choral synagogues was the placement of a separate bimah in front of the Torah ark or the combination of the bimah and the Torah ark in one cohesive unit, which Tzederbaum called “sanctuary” and others called an “altar” or “stage”, since there was no suitable expression for it in Hebrew or in Russian. However, as the examples above have shown, there were choral synagogues that kept the bimah in the center of the hall (Ekaterinoslav until 1884, Riga, St. Petersburg from 1893–1906), and there were synagogues where the bimah was together with the Torah ark, which were not called choral (Irkutsk, Kabansk).

The organ gradually became a necessity in choral synagogues, so that in the last decade of the Russian Empire, the mention of a special place for the organ appeared in the conditions for architectural competitions for choral synagogues (Kharkov and the Peski Synagogue in St. Petersburg) (Il’in 1909, p. 183; Lishnevskii 1912, p. 517). However, the presence of an organ or harmonium seems to be more a sign of status than of religious reform. According to the available descriptions, organs were used during weddings and other events held on weekdays that did not contradict the halakhic prohibition to play musical instruments on Saturday. Only two synagogues in the empire, the Society of Shop Attendants and the Brody Synagogue in Odessa, used an organ on Saturdays and holidays.

Initially, the women’s gallery inside the prayer hall was also considered a sign of a modernized synagogue and was mentioned by observers. However, when the majority of large synagogues were built with interior galleries in the last decades of the nineteenth and beginning of the twentieth century, this feature ceased to be considered an alteration of tradition. From then on, it was the mehitzah, not the gallery, that divided traditionalists from modernizers.