1. Preface

In describing the deep and far-reaching social significance of the Jewish synagogue in the Middle Ages, Simcha Goldin wrote things that seem to be true in every place and time in which an organized Jewish community exists:

Apart from being a place of worship, the synagogue is mainly a public stage on which the drama of the group is preformed, an institution in which the hidden desires of the group are realized, power struggles between groups or status holders take place, and of course the value-based activities of its members is reflected.

Quite similarly, Jacob Katz, referring to the 19th-century Jewish communities in central Europe, described the growing and varied importance of the synagogue in modern times:

And just as social circumstances determined the extent of participation in public prayer, the emphasis on public prayer shaped local realities. The synagogue was given multiple secondary functions as part of the communal administration: It was there that warnings were issued, decrees of excommunication pronounced, and oaths taken […] And the synagogue also fulfilled less obvious social functions. As a regular meeting place for members of the community, it provided an opportunity for purely secular conversations and even for business negotiations […] The synagogue also provided a method of marking off the social strata within the community […] and offered the well-to-do various methods of displaying their wealth.

While both Goldin and Katz referred primarily to synagogues in Europe, it is clear that in the Islamic world, too—since the middle ages, and especially from the early modern period onwards—the synagogue has served both as a ritual center for prayer, study and religious gatherings, and as a social and communal center of dramatic significance.

2 This varied and changing role of the synagogue for its community—as well as its spatial and geographical significance within the local environment—has led to diverse and intensifying research on synagogue landscape in recent decades (including in Israel). This concerns how it reflects population movements in urban space (

Hyman 1987;

Gafni 2011c); the struggle of different communities to define and stabilize their status in an inter-community environment (

Aharon-Gutman and Ram 2018;

Ram and Aharon-Gutman 2017, with regards to the synagogue landscape in the mixed city of Acre); and other demographic and political developments taking place in its local area.

3The multi-dimensional essence of the synagogue in Islamic countries has been expressed throughout history, even in the various denominations of the synagogue in the Islamic sphere: Knesset/Knissa (כנסת/כניסה, a place of assembly [possibly influenced from the Islamic ‘Jameh’, ג’מאע]); Salat (צלאת, a place of prayer); and Midrash (מדרש, a place of study).

4 In addition to these specific uses, various synagogues were used to fortify communal traditions; to commemorate the fallen; to honor friends and donors; and, as in the case of the great synagogue of Aleppo—where the oldest manuscript of the Bible—the

Keter (כתר ארם צובא)—was kept—as treasuries for the community’s most precious holdings.

5 Therefore, exploring the synagogue, as well as the way it was perceived (and later remembered or commemorated) by its community, allows us to better understand the fabric of the society in which it was founded, designed and operated: its aesthetic, spiritual, and ideological preferences, and, of course, also its changing relations with its surroundings and with local governments.

It is of course obvious that there were great differences between the uses and functions of major synagogues—established in the larger cities by the central local communities—and of the hundreds of local synagogues, which served small or rural communities. It is equally clear that there were considerable differences between the way in which synagogues were designed and operated in Islamic countries over many centuries, and the way they were treated and thought of from the mid-19th century onwards (

Gafni 2019, pp. 238–41). Yet, owing to the dramatic significance of the synagogues in shaping and fortifying of the social character of the community—and in consolidating its religious and spiritual identity—it is not surprising that descendants of many communities in Islamic countries that were uprooted from the mid-20th century onward sought to preserve the image and memory of the synagogues which were left behind, and to commemorate them in their new places of residence—both in Israel and in the Diaspora. This ocurred—as will be discussed in the latter parts of this paper—to a certain extent in a similar way to the way in which synagogues that were destroyed in Europe during the Holocaust were commemorated by remnants of their communities in Israel or in other countries.

6In this short paper, I aim to present several manners in which a few of these synagogues—usually the more prominent and significant ones—are commemorated today in Israel, by members and descendants of their original communities, which were uprooted almost 70 years ago. In this context, it should be noted, I do not intend to deal at length with the common and general commemoration, consisting only of a basic commitment to the customs and Halakhot that were practiced in a certain synagogue or ethnic community, but rather to the specific and clear commemoration of particular synagogues in Israel, in one of several manners.

The review of the phenomena presented in this article is only preliminary and is intended to illustrate different types of commemoration—each of which justifies a more orderly perusal. However, the research is based on both a literary review (scholarly, halakhic and commemorative), as well as a years-long field study of synagogues across the country (including interviews with synagogue leaders and other long-time members), which has led to the inspection of other characteristics—visual, cultural and ideological—of the synagogue landscape in Eretz-Israel in modern times.

As will be described and seen from the various cases presented at length—the initial commemoration of the synagogues left behind was rooted in the period before the establishment of the State of Israel, as well as in the state’s early years, but different manifestations of this phenomenon have also occurred—for several reasons—in recent years. This, perhaps, is another indication that the issue of perpetuating and documenting Jewish life in communities from Islamic countries is still very much relevant in Israel’s contemporary cultural and social landscape.

It should be noted that, in this context, the problematic term “Islamic world” denotes communities and synagogues which existed in all predominantly Muslim lands, and therefore encompasses countries throughout much of the Middle East and West Asia (including Turkey), but stretching also to the Atlantic coast of North Africa. True, there were significant differences between Jewish communities in the different geographical areas included in this broad definition. However, the relative similarities between the circumstances which led to the displacement of the various communities and their immigration to Israel, as well as the similar communal and personal challenges faced later by immigrants from these countries—including the common and ongoing struggle to re-shape and consolidate the memory of Jewish life in their communities of origin— enables us to address them jointly (if only in an initial review of this kind).

7 2. The Immigration (“aliya”) from Islamic Countries after the Establishment of the State of Israel: A Historical and Sociological Background

In 1948–1960, the young state of Israel absorbed a particularly large number of immigrants (

Olim), who emigrated from post-WWII European countries as well as from Islamic countries and several other areas (including India). In total, the state absorbed during its first decade close to 900,000 immigrants, of whom close to 400,000 came from Islamic countries: Iran, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Turkey, Yemen, Egypt, Libya, Morocco, Tunisia and Algeria. The uprooting of these communities from their countries of origin, and the Olim’s decision to immigrate to Israel, stemmed from both ideological and practical motives, and from historical events that occurred in Israel itself (with the establishment of the state) as well as in these countries, ideologically and politically (

Tsur 1997, pp. 57–61, 67–76, 80–81).

Although quite a few of the immigrants from the Islamic countries came originally from well-established (and even wealthy) communities, their immigration to the young state was seen by many in Israel as being a “rescue mission”, and was also accompanied by many severe difficulties. This, due both to their unique cultural background—given the significant gaps between them and immigrants from Western countries in general, and the veteran Israeli community in particular—and to various economic, domestic and religious challenges. Israel, which in its early years was experiencing a continuing economic crisis, had to cope with mass immigration while finding temporary (and usually problematic) solutions to housing, employment, education and more. All this while consciously attempting to create a kind of cultural “melting pot”, through which all immigrants from the various countries will consolidate into an Israeli national group with almost uniform cultural characteristics.

Against the background of the objective difficulties in absorbing such mass immigration in a short period of time—as well as a patronizing attitude toward non-western immigrants by a significant number of government officials—the rifts between the various ethnic groups formed severe conflicts, regarding a variety of issues, which even today exist in the Israeli public sphere (

Lissak 1996, pp. 1–19). Thus, the issue of creating a shared memory and a unique Mizrachi-Jewish (or Jewish-Arab) identity—of which the commemoration of the synagogues in the countries of origin is but one expression—is a fascinating phenomenon, which, even if not unique to the Israeli case, has received various and long-standing expression.

8A vast majority of the immigrants who came to Israel from Islamic countries during this period were deeply religious. However, due to the challenges they faced, in the early years it was the state itself that set up synagogues for the Olim, both in the temporary settlements and in the urban neighborhoods and agricultural settlements established for the immigrants during that time.

9 Thus, in 1954, it was reported that more than 1500 synagogues were operating in Israel overall, of which 800 were of Sepharadi or Mizrachi populations (

Broide 1954, pp. 95–96). However, it is self-evident that these synagogues, built by the government, were very modest, and did not resemble at all the synagogues that existed at least in the major cities of the Olim’s countries of origin. Only in the next decades, with the economic and public consolidation of the immigrants themselves—and gradual change in the cultural framework in Israel—larger and more impressive Mizrachi synagogues began to be built, some designed to commemorate—in one way or another—the synagogues which were left behind.

3. Commemoration by Name: From Cairo to Bat-Yam

The most common form of commemoration of the abandoned synagogues in the Islamic world is the use of their name when establishing new synagogues by members or descendants of the original community.

Before reviewing several cases in which this kind of commemoration was used, it should be emphasized that the very process of uprooting synagogues (or whole communities) from the Diaspora, and their immigration to Eretz-Israel, was perceived by Chazal as symbolizing not the disappearance or even destruction of the communities of origin, but rather as a symbol of the future national and religious redemption, and the regrouping of all Jewish people and tribes in Eretz-Israel:

Rabbi Elazar HaKappar says: In the future, the synagogues and the study halls in Babylonia will be transported and re-established in Eretz-Israel, as it is stated (Jeremiah 46:18): “Surely, like Tabor among the mountains, and like Carmel by the sea, so shall he come”.

10

Indeed, it should be noted that even before the establishment of Israel and the uprooting of hundreds of communities, during the second half of the Mandate period and in the wake of the immigration of several hundred Jews from Kurdistan to Eretz-Israel, a number of small synagogues were established in Jerusalem, which both in name and in their declared original year of founding (which was prominently noted on the synagogue front)—were clearly displayed as being a continuation/commemoration of the original synagogues in Kurdistan. This, despite the circumstances of these communities leaving their synagogues behind, was not at all traumatic.

One such case is that of the

Navi Yehezkel (נביא יחזקאל) synagogue, established by Jews from Amadiya in the

Zichron Yosef neighborhood in central Jerusalem, and presented as being established originally under this same name in Amadiya in 1018 and then again in Jerusalem in 1931 (

Figure 1). Another example is the neighboring

Bar Ashi (בר אשי) synagogue, presented as being established under this name in the Barashi village in 1783 and then again in Jerusalem in 1934 (

Figure 2).

11 Yet, it should be noted that, in these cases, aside from the immediate desire for commemoration, the usage of the original names of the synagogues in Kurdistan had also another purpose: to establish and reinforce the status of the Kurds among the Jewish community of Jerusalem—both in their own eyes and in the eyes of other local communities. This was done by emphasizing that these small communities also had ancient Jewish roots and traditions in their country of origin, stretching all the way back to Ezekiel the prophet and to the

Amoraim of Babylon.

12Naturally, after the establishment of Israel and the uprooting of hundreds of Jewish communities from the Islamic countries, initiatives such as these became much more common, as quite a few abandoned synagogues were commemorated in new communities, by using the name of the original synagogue for the new one. Thus, for example, several synagogues of Jews of Egyptian origin, which were established in Holon, Bat Yam, Jerusalem and other cities, were given the name

Ahava VeAchva ((אהבה ואחווה, commemorating the name of the central yeshiva (and house of prayer) which was established in Cairo in 1928 (this even when the new synagogue in Israel, bearing the same name, was actually only a simple prefab structure).

13 Similarly, a synagogue which was established in Ashkelon by Olim from Tunis and Jerba was named

Salat Al-Khoury (צאלת אל חורי) after a synagogue which operated under the same name in Jerba, Tunisia. Other cases include the

Midrash Silwerah (מדרש סילוירה) Synagogue of Aleppo Olim (established earlier, in the 1920’s, and bearing the same name as a synagogue in Aleppo) and The

Twieg (טווייג) Iraqi synagogue, both in central Jerusalem,

14 as well as the

Or Torah synagogue in Acre, also known as

La Geriba (the wonderous), after the well-known Jerbai synagogue bearing the same name (

Figure 3) (

Bedash 1995).

As noted earlier, in some cases, the renewed name of the synagogue was known to have additional social significance, within the specific ethnic community or outside of it. Moreover, a few decades later, apparently many of the worshipers have ceased to remember the original synagogue that the current synagogue commemorates. However, the strict usage of the original name usually continues, and, in some cases, it is still very significant, at least in the eyes of some of the older worshipers.

4. A Religious Artifact as a Means for Communal Memory

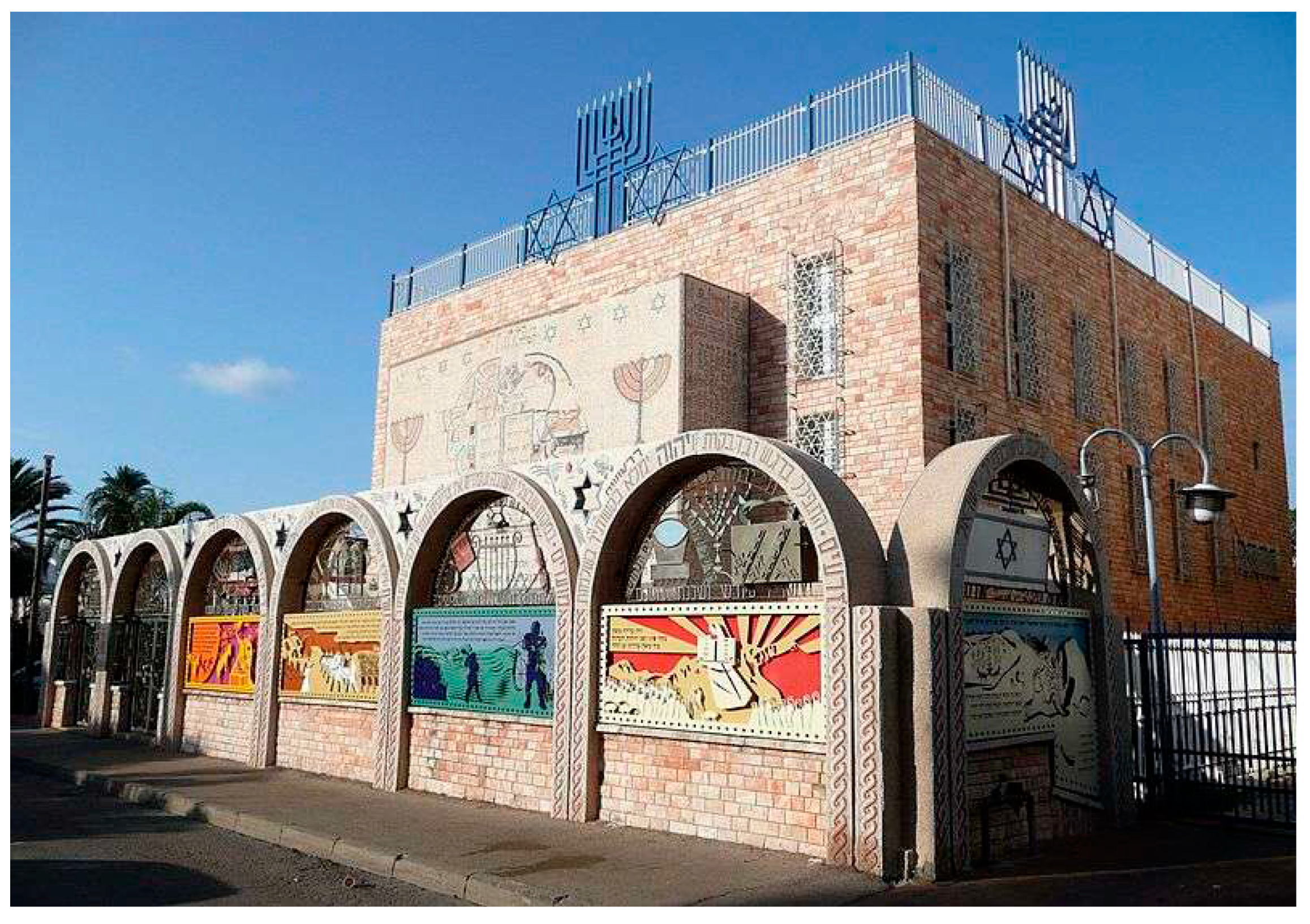

Alongside the usage of the original synagogue names, a different manner in which several synagogues are commemorated today is by displaying their picture—or, in other cases, a certain religious artifact from the original synagogue—within the new one, sometimes in a particularly conspicuous place.

For example, a colored picture of both the La Greiba Synagogue in Jerba and the Tunis Great Synagogue is included in one of the main stained-glass windows of the famous Or Torah (or La Greiba) Synagogue in Acre, whose founders well remembered the two original synagogues in their days of glory, and wished to express their commitment to their heritage (

Figure 4). In this case, it should be noted that the integration of the images of the synagogues of Tunisia was even more significant. This is due to the synagogue founder’s (Zion Ba’adash) attempt to design it in a rich, meticulous interior manner (including hundreds of mosaics and dozens of colorful stained glass windows), while deliberately blending the new and the old, and landscapes of Eretz Israel alongside traditional, Halakhic and ethnic components. Ba’adash’s successful initiative—which turned the Unique synagogue in Acre into a well-known tourist attraction, visited every year by thousands, including many of Tunisian origin from Israel and abroad—effectively means that commemoration of this kind is even more profound, at least in cases such as these.

15In other places, rather than using the picture of the commemorated synagogue as an ornament, a certain original item from the old synagogue was used, serving both its original purpose as well as providing a means for commemoration of the synagogue from which it was taken. One such case is a prayer board in the

Magen HaShalom (מגן השלום) synagogue in Ramle, founded by Jews of Pakistani (and Indian) origin and also bearing the name as the original synagogue in Karachi.

16 The small prayer board is written in Marathi, the language spoken originally by many of the

Olim, and which almost none of the current, younger generations of the community can speak or even read (

Figure 5,

Figure 6 and

Figure 7). Its purpose, therefore, is solely to commemorate the original synagogue, alongside several chandeliers from India, which were brought to Israel and installed in the synagogue for the same purpose (

Gafni 2008b).

17Another example of commemoration of the same manner is a small piece of marble flooring from the

Gerush (גירוש) synagogue of Bursa, Turkey, which has been installed and displayed for several decades—very close to the Holy Ark!—in the small synagogue of

Olei Bursa (עולי בורסה) in central Jerusalem (

Figure 8) (

Gafni 2008a, pp. 182–84). Aside from this relic—and owing to the special communal importance of the Gerush synagogue through many generations—the founders of the small synagogue in Jerusalem also brought one of the old

Torah scrolls that were used in Bursa for many years, and it is currently being kept and used sparingly in the synagogue in Jerusalem.

18 Other

Olim from Turkey, originally from Izmir, placed several original artifacts from the “Portugal” synagogue in the small

Yismach Moshe (ישמח משה) synagogue, which they established in the Yemin Moshe neighborhood in 1951 (

Gafni 2008a, p. 39). This, too, for their continual use and for the commemoration of their old synagogue.

5. Re-Creating the Image, Consolidating Ethnic Identity

Unlike the commemoration of a synagogue via a certain name or item from the original synagogue—actions which usually do not require a significant financial investment—a number of synagogues have been commemorated in a much clearer manner: Their original image and structure have been recreated and reconstructed in their original form—albeit not always with the original size and scale—as the initiation of several institutions throughout the country.

One of the most prominent cases which illustrates this phenomenon is the

Bushaeff (בושייף) synagogue in Moshav

Zeitan, which, in several aspects of its interior appearance, preserves the original synagogue whose name it bears, which operated for several centuries in the town of Zliten in Libya (as one of the most sacred sites for Libyan Jews) (

Benattia 2007, p. 210). In this case, too, the physical commemoration of the sacred synagogue—initiated by the Daboush family—has had a profound significance on the Jewish-Libyan community in Israel, as it has become in itself a pilgrimage site for many Libyan Jews several times a year, thus strengthening communal ties and ethnic identification (

Figure 9).

19 Another example of this kind of commemoration is the Jerbai synagogue in the southern city of Netivot, built during the 1970s under the initiative of the local chief rabbi, Raphael Tzaban, and widely known also as La Greiba (like a number of other synagogues of Tunisian Jews nationwide) (

Figure 10).

While the Busheif synagogue and the Jerbai synagogue of Netivot were founded as, and have been operating first and foremost as, local synagogues, serving their congregation three times a day, few other synagogues were commemorated likewise, except within ethnic museums or heritage centers, where they serve mainly as tourist attractions or as educational sites. The most prominent example for this manner of commemoration is the Great Synagogue of Baghdad (“Slat Al-Kbiri”), which was the most ancient synagogue in the city (traditionally dated as early as around the fifth century B.C.E.). Its structure is replicated within the Babylonian Jewish heritage center in Or Yehuda, in a space which is about an eighth of the synagogue’s original size. The replica includes a Tevah (reading podium, תחבה, בימה), which is an exact replica of the original one from Bagdad, and is undoubtedly one of the highlights of the visit at the heritage center, visited by many thousands every year.

20 Not surprisingly, the dedication of the museum itself, in 1988, was held within the reconstructed synagogue, which was the center of attention on that occasion. Furthermore, its re-creation was seen as a joint communal affair, as its design was planned also according to many oral testimonies of the community’s elderly (

Avishur 2006, p. 73).

Another example is a small synagogue from the city of Tlemcen (תלמסאן), Algeria, which was incorporated into the North African Jewish heritage center in Jerusalem (albeit also not in its original size). Although these two synagogues do not serve as prayer houses on a regular basis—except during special events that take place from time to time in both heritage centers—their re-creation and restoration is of great significance: both in completing the visitor’s experience of the ethnic culture and identity displayed in the museum, as well as in fortifying the collective memory and identity of the communities themselves, by expressing their emotional connection with the many houses of prayer that they were forced to abandon upon immigrating to Israel.

Finally, it is also worth mentioning that some models of synagogues from Islamic countries—including the Ibn Danan synagogue of Fez, Morocco—are included in the permanent synagogue display at the Museum of the Jewish People at Beit Hatfutsot, as part of a 21-piece display of synagogue models from all over the world (

Figure 11).

6. Liturgical and Geographical Documentation

The different forms of commemoration that were briefly presented thus far were those which included some kind of physical or Semitic commemoration—of varied significance or emphasis—which aimed to commemorate specific synagogues that operated in Islamic countries, prior to the abrupt uprooting of the communities. Still yet a different manner of commemoration, of the liturgical-halakhic aspect, is that which is expressed in the attempts of various communities in Israel to strictly and faithfully follow the halakha and custom identified with a particular synagogue, which is perceived—for one reason or another—as worthy of copying and preserving its customs within the new synagogues. One such example is the Al-Utsta (אלאוצטא) synagogue in Sana’a, Yemen, which was established in the 18th century by Rabbi Shalom Araki and served as one of the most important synagogues in Yemen until the establishment of Israel (

Gimani 1993, pp. 134–44).

21 Indeed, in several Yemenite synagogues in Israel that follow the

Shami (שאמי)

Nussah (custom of prayer), the congregants try to follow its customs and traditions as best as possible. It is therefore not surprising that many of the books and scrolls from this synagogue were transferred in an organized manner to a Yemenite synagogue in Ramat Gan (Neveh Shalom HaCohen), several years after the community’s uprooting, while the Yemenite synagogue Beth Yehuda (בית יהודה) in the Katamon neighborhood of Jerusalem—where the last rabbi of the original synagogue in Sana’a, Saadia Ozeri, lived briefly—also shapes its prayer according to its exact halakhic and traditional customs.

22 For this purpose, rabbis and scholars have been working (in several different ways) to document in a meticulous manner the customs of this synagogue, as well as several other prominent synagogues in Yemen. Other examples of this sort are the ongoing efforts of a number of prominent Rabbis of Tunisian (or Jerbai) origin to preserve and disseminate the exact custom (

nussah) of prayer used originally in the Jerba synagogues, which have led—among other things—to the production of a number of

Siddurim (prayer books) purporting to preserve it most accurately.

23 Likewise, efforts to restore the exact prayer custom of the Bagdad synagogues have also been taking place during the past decades, resulting again in the production of new Jewish-Iraqi prayer books.

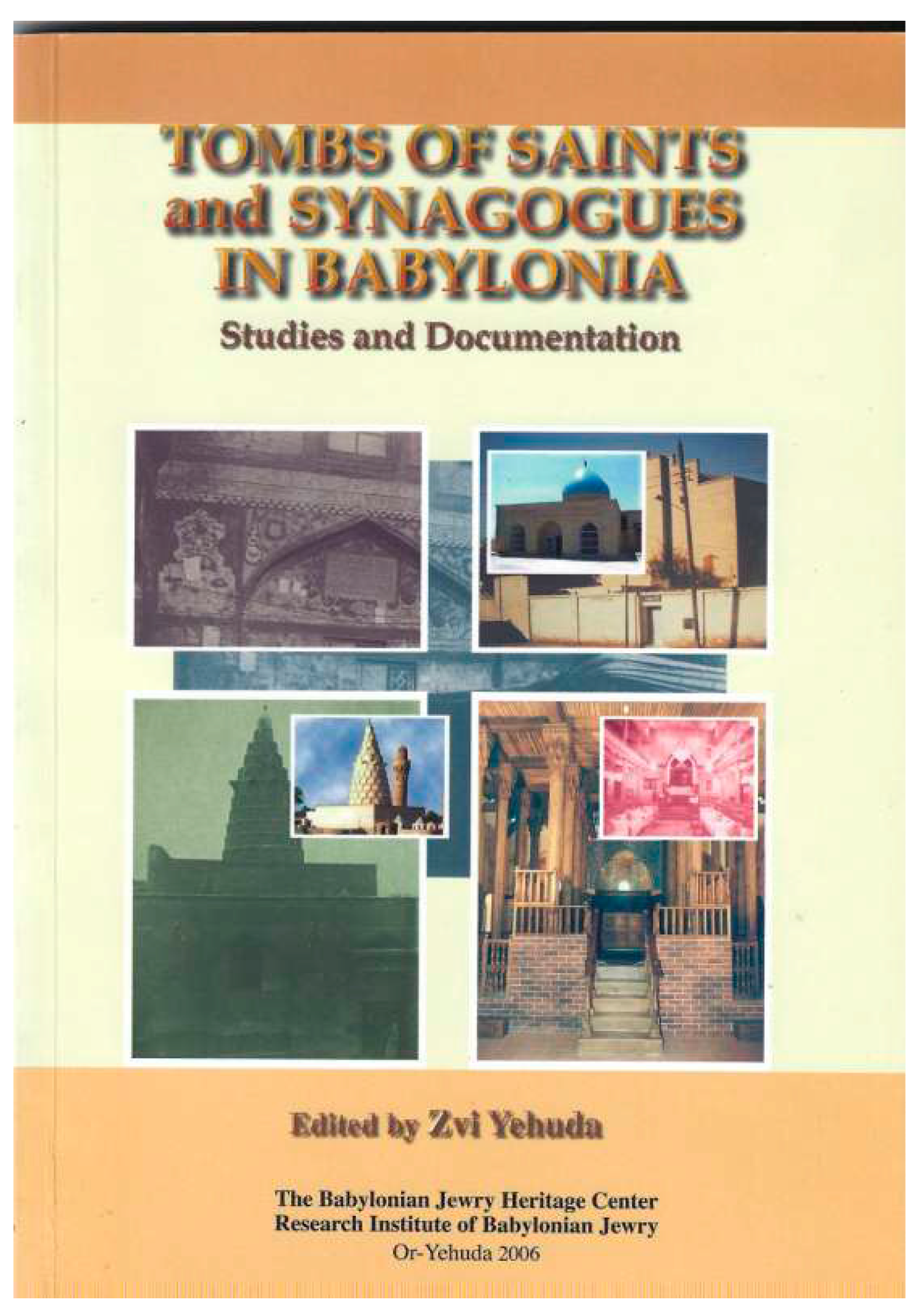

24Alongside this liturgical and halakhic documentation, the main purpose of which is to enable the preservation of religious customs by the next generation, many synagogues—especially those which operate in the larger cities—have been documented from a relatively detailed historical and geographical perspective. One of the first examples of such documentation of synagogues in a defined geographic area is the topographical survey of the 82 synagogues that operated in Tunis in 1956. This survey was conducted by Avraham Hatal, according to his testimony, with the clear purpose of preserving their memory, knowing that most of them will cease to operate within a short period of time—as indeed happened (

Hatal 2005, p. 254). More recent surveys include, for example, Zvi Yehuda’s survey of the synagogues of Baghdad (

Figure 12) (

Yehuda 2006, pp. 109–20), and several more surveys of this kind have been conducted over the past few years. Today, obviously, reviews, surveys and various lists of synagogues in Islamic countries can be found in the digital sphere. However, it should be emphasized that most such lists and surveys are non-systematic and only partial, usually including only the most basic details about each synagogue, rather than detailed information about its appearance, customs, or ideological, religious, and social character.

7. Between Commemoration of the Past and Memory of Destruction

As stated at the outset, the commemoration of synagogues from the displaced communities of the Islamic world in Israel can be compared to the commemoration of synagogues or communities that were destroyed in Europe during the Second World War. This is true both in terms of the motives and of the practice.

The commemoration of synagogues which were destroyed during the Holocaust—usually within local new synagogues built in Eretz-Israel—was at the center of a public debate that began as early as the 1940s, which revolved around the “correct” architectural style of the synagogues that were being built at the time, and whose worshipers identified themselves with the Zionist national movement (

Gafni 2017, pp. 102–3;

2014). This discussion came to the fore again during the 1950s, with the young state’s initial involvement in the establishment of synagogues throughout the country, and was also expressed by the initiative to bring to Israel several synagogues and many religious artifacts from Italy, under which the Coneliano Venetto synagogue was also rebuilt in Jerusalem in the 1950s (

Broide 1954, p. 89).

25 From then on—and especially during the 1970s—more and more types of commemoration of fallen communities and synagogues spread throughout the country (

Tidor-Baumel 1995). This was achieved through the founding and calling of synagogues in the name of communities that had been destroyed (such as the synagogue named after the Auschwitz saints in Beer Sheva); the setting of memorial plaques in hundreds of synagogues across the country; synagogue architectural design that was meant to suggest the image of the founders’ original community (such as the Heichal Yehuda synagogue in Tel Aviv, shaped like a seashell to imply Thessaloniki, located on the beachfront) (

Simhony 2019, pp. 185–86;

2020, p. 12); the hanging of pictures and illustrations of destructed synagogues in new ones, founded by the descendants of the original community (such as the “Vishwa” synagogue in Bnei Brak); and in many other ways. In some of the synagogues, even tiny museums have even been set up, presenting to the visitors various episodes of extermination (such as the Struma Saints Synagogue in Beer Sheva).

Not surprisingly, this phenomenon has also prevailed in many communities outside of Israel, and it seems to have become more and more prevalent through to today, especially in Eastern Europe, where the synagogues’ significance as museums and tourist sites clearly exceeds their religious and ritual value.

26Yet, after all, there still seem to be some differences between the two phenomena—however similar they may seem. First, an initial review reveals that while the commemoration of synagogues that were destroyed during the Holocaust was a common phenomenon as early as the 1950s, in the context of the synagogues abandoned in the Islamic world, this usually happened only later. This is perhaps due to the fact that, during the first decades in Israel, immigrants from Islamic countries were engaged first and foremost in personal and communal struggle for economic, social and religious survival, and much less in the shaping of the memory and commemoration of their communities and synagogues of origin. It was only when descendants of these immigrants settled down—in various respects, including politically—that they began to engage more intensely in restoring the image of their communities of origin in the public memory. Moreover, while the commemoration of synagogues in Islamic countries was often accompanied by a desire to redress social, economic and cultural injustice, it was with a much clearer feeling of consensus—and without any political significance—that synagogues that were destroyed in the Holocaust were commemorated.

However, despite the various differences between the two cases, the practice itself seems to be quite similar, and this in itself is not surprising.

8. Discussion

The phenomenon briefly presented in this paper refers to various types of synagogue commemoration, occurring for several decades all over Israel, in the urban, agricultural and communal sphere, by members of various ethnic groups—Jews from Turkey and Babylonia, Syria and Kurdistan, Tunisia and Morocco, Yemen and Egypt. This is perhaps further evidence for the fact that the very need to commemorate the synagogue of yesterday, as well as the communities which were left behind, is common to all such communities, perhaps recently even more than ever. Furthermore, although only a few dozen examples have been presented here, it is most probable that a more comprehensive field study of synagogues throughout the country will reveal many more cases of such commemoration, and perhaps also new types of such activities—both material and virtual.

As noted, with the exception of a few specific cases (most notably the Or Torah Tunisian Synagogue in Acre), such activities of communal and synagogue commemoration rarely took place during the first few decades after the communities’ immigration to Israel. This is mainly due to this population’s intensive and long-standing pre-occupation with the economic and communal challenges of everyday life, but also—as Avi Picard has shown—due to their basic aspiration to intervene in the Israeli community (that of actual or adopted Western characteristics), and their reluctance to emphasize the non-European (sometimes even Arabic) characteristics of their communities of origin. Things gradually changed from the 1970s onwards, due to the social establishment in Israel of the second and third generations of immigrants, as well as other changes in the status of these communities in the Israeli public and political arenas. Indeed, from that point onwards, a wide and varied activity of re-establishment of Mizrachi (or non-European) Jewish identity began, with reference to cultural elements, as well as folkloristic, religious and other components in the identity of Jewish communities from the Islamic world (

Picard 2017,

2016). All this is part of the desire to place the Mizrachi culture at the center of the public sphere, as a relevant cultural alternative in the gradually deconstructing post-modern and multicultural society in Israel. The commemoration of synagogues, therefore, should be seen as part of a much broader struggle—one which the legislation of a national day marking the departure and deportation of Jews from Arab countries (and Iran) in 2014, was also a significant part of.

As mentioned, this phenomenon characterizes various ethnic groups, but the more politically (and perhaps economically) consolidated communities have clearly succeeded in creating more significant commemorative and memorial projects, such as the Babylonian and North African Jewish heritage centers—each one consisting also of a restored or reconstructed synagogue. However, it should be noted that even the more prominent cases were initially private or communal projects—only sometimes accompanied at a later stage by state or municipal sponsorship.

Naturally, synagogues that are commemorated in these or other manners are usually the larger, more prominent and significant synagogues which operated in the countries of origin—from a public, religious, social, and sometimes even mystical perspective. By contrast, the thousands of smaller rural and local synagogues which existed in the Muslim world are much more difficult to commemorate physically—especially in light of the fact that we do not have good visual documentation on most of them—and are likewise very difficult to document and perpetuate on a historical, cultural and religious level (

Gafni 2019, pp. 238–40). However, in some cases, the synagogue being commemorated was originally one of only local importance, and its very commemoration, it seems, attests to the profound significance of the synagogues for each local community, and to how traumatic their departure was, with the uprooting of the communities from the Muslim countries and their immigration to Israel.

In light of this, it seems that the public and academic world should welcome, initiate and fortify public or academic preoccupation with the synagogues of the uprooted communities in the Islamic world. This should not be in the context of claims for restitution of Jewish property and compensation of refugees, but as a means of better knowing and describing their image in a full, richer and more accurate manner—both originally, as Jewish communities operating in the Islamic world, and also after their uprooting and migration to Israel, as ethnic communities struggling to maintain and consolidate their former communal identity, several generations later.