During the Medieval period, holy sites in the Middle East were often associated with a biblical figure, usually one whose personal history was interwoven with a certain geographical space. Foundational myths related the event that imbued the site with holiness and its relationship with the holy person associated with it. Sometimes, this was an event mentioned in the Bible, and on other occasions, it was a miracle or supernatural occurrence that became a well-known tradition, imparted orally until it was recorded in textual sources.

The manuscripts discussed in this article originated from Egypt and the Land of Israel, the very geographical space in which these sites were located. The illustrations are accompanied by clear identifying captions, indicating that they represent a known and familiar place. This raises the question of whether the architectural representations before us constitute a faithful reflection of reality. Is it possible to see them as firsthand testimony regarding the appearance of a place, or are these visual patterns that contain no unique and realistic elements of the actual site? Or, perhaps, the various images are symbols, and their elements and design were intended to express a concept or idea? An examination of the depictions reveals a multifaceted answer that I will attempt to explain.

1. Kanīsat Mūsā in Egypt

Kanīsat Mūsā was a place of pilgrimage and a holy site associated with the biblical figure of Moses. The site was located in the village of Dammūh, several kilometers southwest of Fusṭāṭ, on the western bank of the Nile. According to local tradition, Moses sojourned in Dammūh after leaving the Pharaoh’s presence to pray outside the city, as related in Exodus 9:29:

And Moses said unto him: “As soon as I am gone out of the city, I will spread forth my hands unto the Lord; the thunders shall cease, neither shall there be any more hail; that thou mayest know that the earth is the Lord’s.”

Scholars concur with statements found in various sources, according to which a pilgrimage site and holy place associated with Moses existed at Dammūh as early as the 1st century CE. Studies regard Kanīsat Mūsā as the holiest and most important and central pilgrimage site for the Jews of Egypt throughout the entire medieval period. In 1498, the Mamluk sultan issued a decree ordering its destruction, although apparently, remnants remained standing, because testimonies from the mid-sixteenth century describe pilgrimages to Dammūh.

6Studies concerning the site draw on a number of sources. The central and most detailed source is found in the writings of the learned Egyptian religious figure al-Maqrīzī (1364–1442). His topographical-historical work, which dates from the beginning of the fifteenth century, offers an extensive depiction of Dammūh and traditions regarding it.

7 An earlier source is the work of the Armenian writer Abū Ṣāliḥ, which describes Kanīsat Mūsā as a holy place of Jews that contained gardens and a well and was surrounded by a wall.

8 Later, the history of the site was also described by Yosef Sambari, an Egyptian Jew writing in the seventeenth century who drew extensively on al-Maqrīzī. In addition to these chronicles, the documents of the Cairo Geniza serve as a valuable source regarding the site. Kanīsat Mūsā also appears in lists and accounts written by Jews of the Middle East and travelogues of European Jews. The earliest and most famous among the latter is the travelogue of Benjamin of Tudela.

9 A modern scholarly article about Kanīsat Mūsā was published by Joel Kraemer.

Until now, scholars have devoted relatively little attention to the visual appearance of Kanīsat Mūsā. However, an elaborate and detailed description of the site appears in a recently discovered source known as the Florence Scroll.

10 The illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā in this scroll is accompanied by captions describing in detail the traditions associated with the place that are not known from other sources.

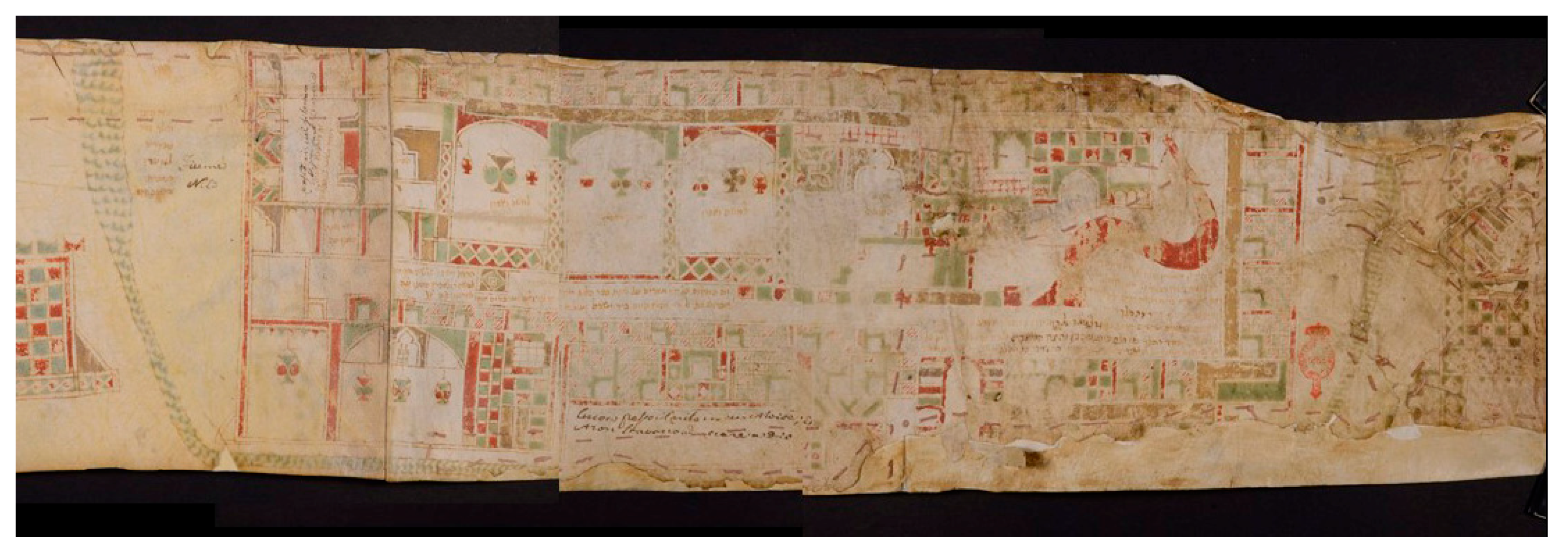

11The illustration depicting Kanīsat Mūsā appears in the first part of the Florence Scroll, and it is among the largest illustrations therein. It is around 48 cm wide and it fills the entire page of the scroll, from the upper to the lower margins (

Figure 1). The illustration presents the site from two different angles: an overview from above and a view of the internal elements from a horizontal perspective in a cross-section. Despite the current condition of the illustration, it is possible to discern a site encircled from three sides in a frame, which apparently represents a wall. Inside this are various areas distinguished from one another by recurring visual motifs, floral guilloche decorations, and architectural elements that are accompanied by identifying captions. Although some parts of the illustration are damaged and their color has faded, the various captions enable us to understand its details.

Within the wall that apparently defined the compound in Dammūh are two sections of text. The first section from the right appears under a twisted image in red. The text indicates that this represents a holy tree. This tree is mentioned in almost all sources concerning Kanīsat Mūsā, although the Florence Scroll offers a detailed description of its history and the miracles attributed to it that are not found in other sources.

12 The twisted figure of the tree is connected with one of the famous miracles that occurred at the site: when the Mamluk ruler in Cairo sought to cut down the holy tree to build a palace, the tree miraculously became twisted overnight. It was so ugly that it was not suited to building the king’s palace and, therefore, he commanded that it should remain untouched.

The second section of text appears on the left-hand side of the illustration and provides details about the site. The writing is difficult to decipher, but it is possible to identify an opening sentence noting the geographical location of Kanīsat Mūsā on the bank of the Nile, and a closing sentence that indicates the times of pilgrimage to it as the three pilgrimage festivals. Apparently, this mainly referred to the period of the

Ziyāra journey undertaken by Jews of the Middle East during the spring months.

13This section of the text also describes secondary holy spaces, perhaps a kind of prayer chapel, dedicated, apart from Moses, to his brother Aaron, who accompanied him on his visit to the Pharaoh’s palace, and to the prophet Elijah. The tradition connecting Elijah to Kanīsat Mūsā can also be found in the list of holy places from the end of the fifteenth century compiled by Rabbi Yosef Halevi Bar Nachman.

14 2. The Synagogue at Kanīsat Mūsā

The visual depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā in the Florence Scroll offers valuable information, supplementing that which can be gleaned from the sections of text integrated therein. Moreover, it appears to reveal facts previously unknown to scholars concerning the site’s appearance.

At the center of the left part of the illustration are three prominent vaulted spaces, all of which bear an identical caption: “To Moses and Aaron”. On the upper left-hand side of the illustration is an image, alongside which is a caption indicating that this represents the hidden well in which Moshe washed before he began his prayers.

15 In addition to the various spaces identified with captions, an analysis of the illustration also reveals two different places of worship within the compound. One, which is clearer, is located on the bottom left of the illustration and is identified as a place of worship only by means of a visual motif: an image of a niche with a pointed horseshoe arch, at the center of which is a Torah scroll. The image of the niche is apparently a representation of the

heiḥal—the name used by the Jews of Spain and the Middle East for the Holy Ark in which the Torah scrolls were kept, or in the local language,

hēkhāl.

16 Such wall niches are characteristic of synagogues in the Mediterranean basin, similar to the niche that has survived in the synagogue at Dura-Europos, which dates back to the third century CE.

The second place of worship in the compound is difficult to discern at first because it is identified mainly through the accompanying text. To the right of the three vaulted spaces dedicated to Moses and Aaron appear the words “the place of the

teiva”. In the illustration, we see a flight of steps leading to the

teiva, the reading platform, similar to the steps known in synagogues that contain a large raised

teiva sometimes built partially from stone.

17 To the left of the three spaces and level with the

teiva/platform is an image of a niche with a trefoil shaped arch, which today, appears to have been cut off, accompanied by the caption: the

heiḥal. The placement of the two foci, the

heiḥal and the

teiva, on the same level at the two ends of the walled courtyard may suggest that the illustration depicts a place of worship open to the sky that was located in the inner courtyard of the enclosed compound, similarly to other synagogues in the Mediterranean basin and in Asia, as documented by David Cassuto.

18 In open synagogues, the main

heiḥal, in which the Torah scrolls were kept, was located on the wall of the courtyard facing in the direction of Jerusalem, and it was also known as

heiḥal hakadosh (the holy ark). In addition to the main

heiḥal, there were often two additional small niches—

heiḥalot—that were also used for Torah scrolls.

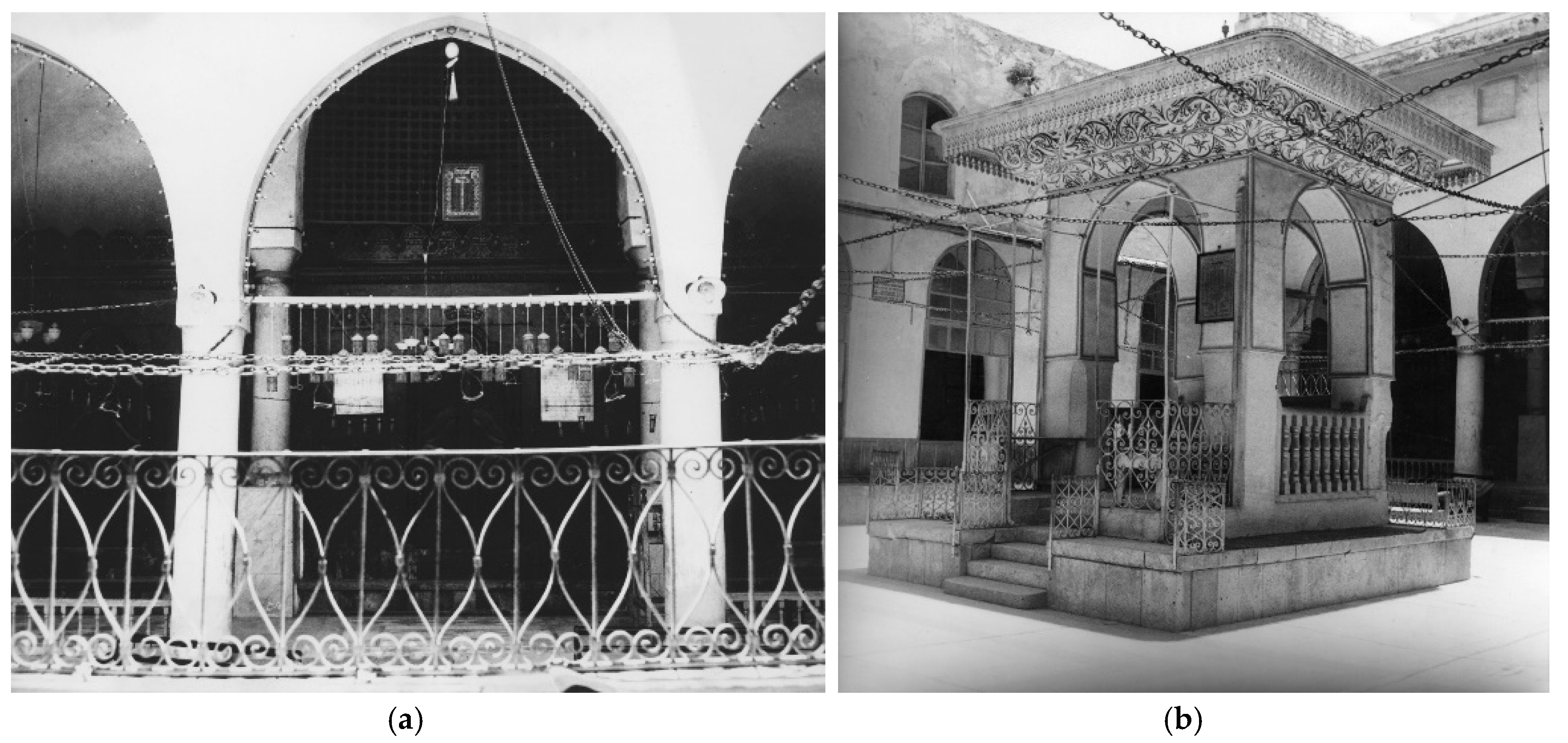

19 The identification of the elements of the illustration as depicting an unroofed synagogue helps us understand the purpose of the three large vaulted spaces dedicated to Moses and Aaron. These spaces apparently depict the

heiḥalot. Despite the similarity to the term used for the place in which the Torah scrolls were kept, this name was also used in open synagogues for chapel-like spaces located around the unroofed courtyard. Their open side faced the courtyard, and every

heiḥal contained a stone bench on which worshippers sat. For comparison, see the photos of the famous open synagogue of Aleppo (

Figure 2).

It was customary that a courtyard housing a synagogue also contained a well or cistern for drinking and washing before prayers, apparently influenced by the Muslim custom of washing before prayers in the mosque.

20 In the illustration of the open synagogue in Dammūh, the well appears on the upper left-hand side and is identified as the hidden well of Moses.

According to Cassuto, open synagogues were sometimes called “summer synagogues”, and the roofed synagogue adjacent to them was intended for use in the winter. The illustration in the Florence Scroll seems to indicate that the wintertime place of worship is located in the lower left section of this illustration.

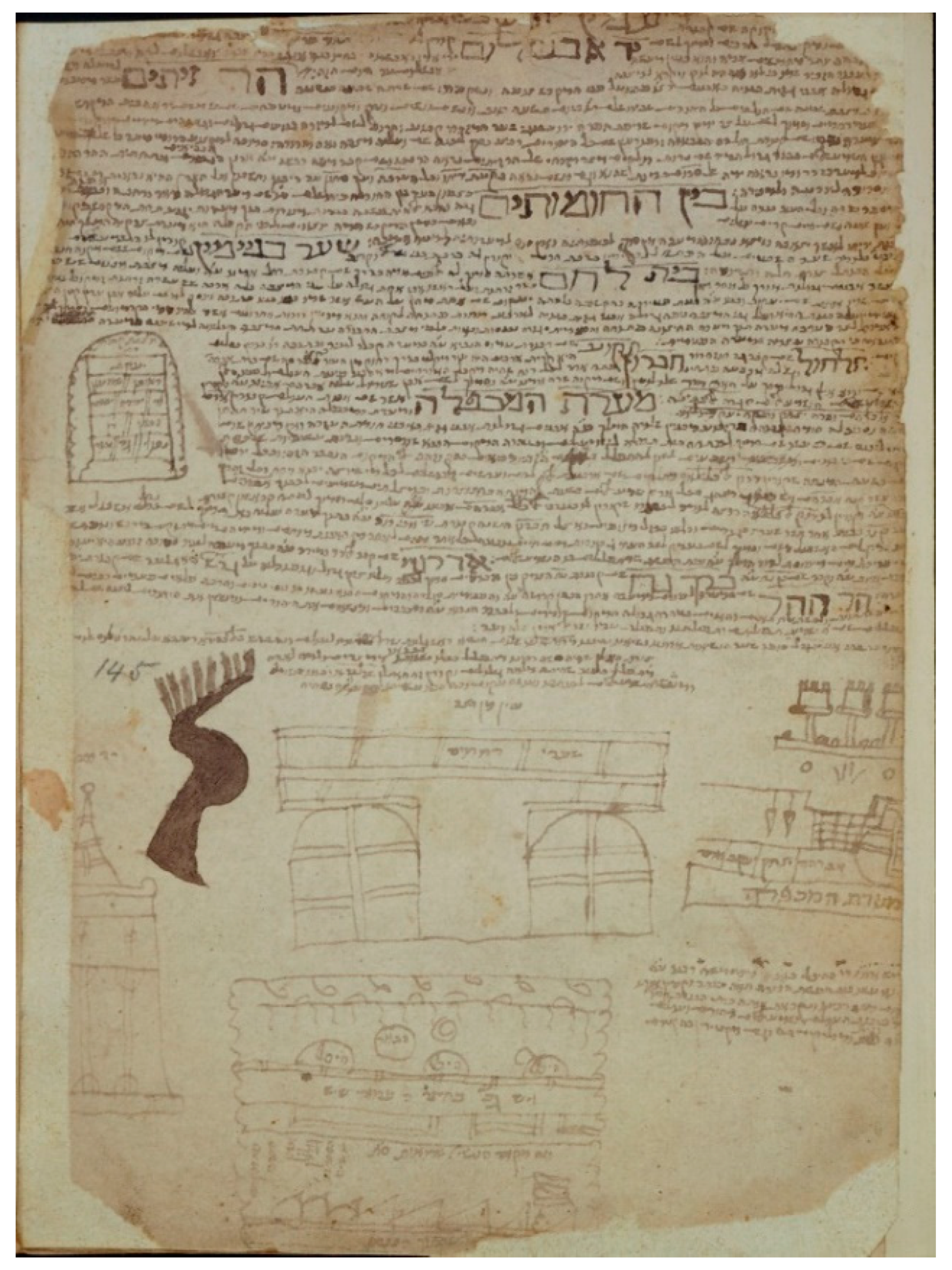

My proposal that the illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā in the Florence Scroll depicts an unroofed place of worship is supported by an illustrated list of holy places known as the List of Yitgaddal. This list appears on a small page of paper, which measures around 20 cm high by around 14.5 cm wide.

21 It includes a small number of ink drawings of holy places: Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh and the holy tree that grew there; Rachel’s tomb;

Sha’arei Rahamim (The Golden Gate); Absalom’s Pillar; and the Cave of Makhpela (

Figure 3). The manuscript includes a colophon containing the author’s name,

22 “Yitgaddal, Scribe of the Nasi’s Gate”, and noting that it was written in Cairo, “on the Nile River”. Scholars are divided regarding the date of the manuscript’s composition. According to E. Reiner, based on the name of the author, who is known from other sources, the terminus ante quem of the manuscript is 1341. S. Zucker and Z. Ilan disagree with this identification; in their opinion, the manuscript is a sixteenth century copy of an earlier manuscript.

23 An analysis of the illustrations in the manuscript reveals, in my opinion, that it was written by the author, and thus, both the List of Yitgaddal and the Florence Scroll were created by the members of the Jewish community of Fusṭāṭ-Cairo in the first decades of the fourteenth century.

24The depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā in the List of Yitgaddal appears in the center of the lower part of the list, and above it, to the left, is the holy tree. Kanīsat Mūsā itself is not mentioned at all in the body of the text. Under the colophon, at the end of the list, the author added three lines describing the tree and its miraculous transformation. An additional section of five lines, the beginning of which is now cut off, appears to the left, below the illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā. It describes the well located behind the

heiḥal and the pilgrimage of Jews and Muslims to the place, as well as the rituals of lighting candles and burning incense.

25 The format of these textual descriptions seems to indicate that they were later additions by the author, and it is likely that all the illustrations (apart from Rachel’s tomb) concentrated in the lower part of the page also constituted part of this addition. It is reasonable to presume that this addition was included close to the writing of the list itself, perhaps even when the author returned from his journey to the Land of Israel to his home in Egypt.

The illustrations of the holy places in the List of Yitgaddal are very simple; they are ink drawings by the author himself, who was not a practiced illustrator. Thus, the illustrations are of a very different quality to those in the Florence Scroll. Despite this difference, it is important to note that the appearance of Kanīsat Mūsā in the List of Yitgaddal also presents the site from a combination of two perspectives, providing a general overview of the structure from above and the internal elements from a horizontal perspective. This simple depiction is not as detailed as the illustration in the Florence Scroll. However, the captions adjacent to some of the elements aid our understanding somewhat.

The illustration depicts a rectangular compound divided into three parts. In the upper part are three vaulted images identified as

heiḥalot. Perhaps, these are the chapels in which the worshippers sat, identified as the vaulted spaces in the illustration in the Florence Scroll, or the three holy niches in which the Torah scrolls were kept. An elliptical figure in the space between two of them is identified as the well. The well in Kanīsat Mūsā is mentioned in most historical sources about the place.

26 It seems that this figure corresponds with the well in which Moses washed himself, as depicted in the Florence Scroll. Between the two sections is a caption describing the courtyard in the compound, which contained five marble pillars.

27 This supports my claim that the place of worship was located in an unroofed courtyard. Moreover, the location of the well within the architectural structure indicates that it was open to the sky.

This claim is also supported by a description of the structure of Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh in one of the early versions of a text describing holy sites visited on the

Ziyāra journey, known as

Yihus ha-Avot.

28 This version of the text relates that the holy tree grew “in the

azara [courtyard]”.

29 The image of the prominent, twisted tree in the depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā in the Florence Scroll indeed appears within the walled area, close to the raised platform/

teiva.

3. Torah Scrolls

We have identified the vaulted space at the bottom left-hand corner of the illustration in the Florence Scroll as a winter synagogue housed in a roofed structure. This conclusion is based on the presence of an image that, as was noted, depicts the niche of the

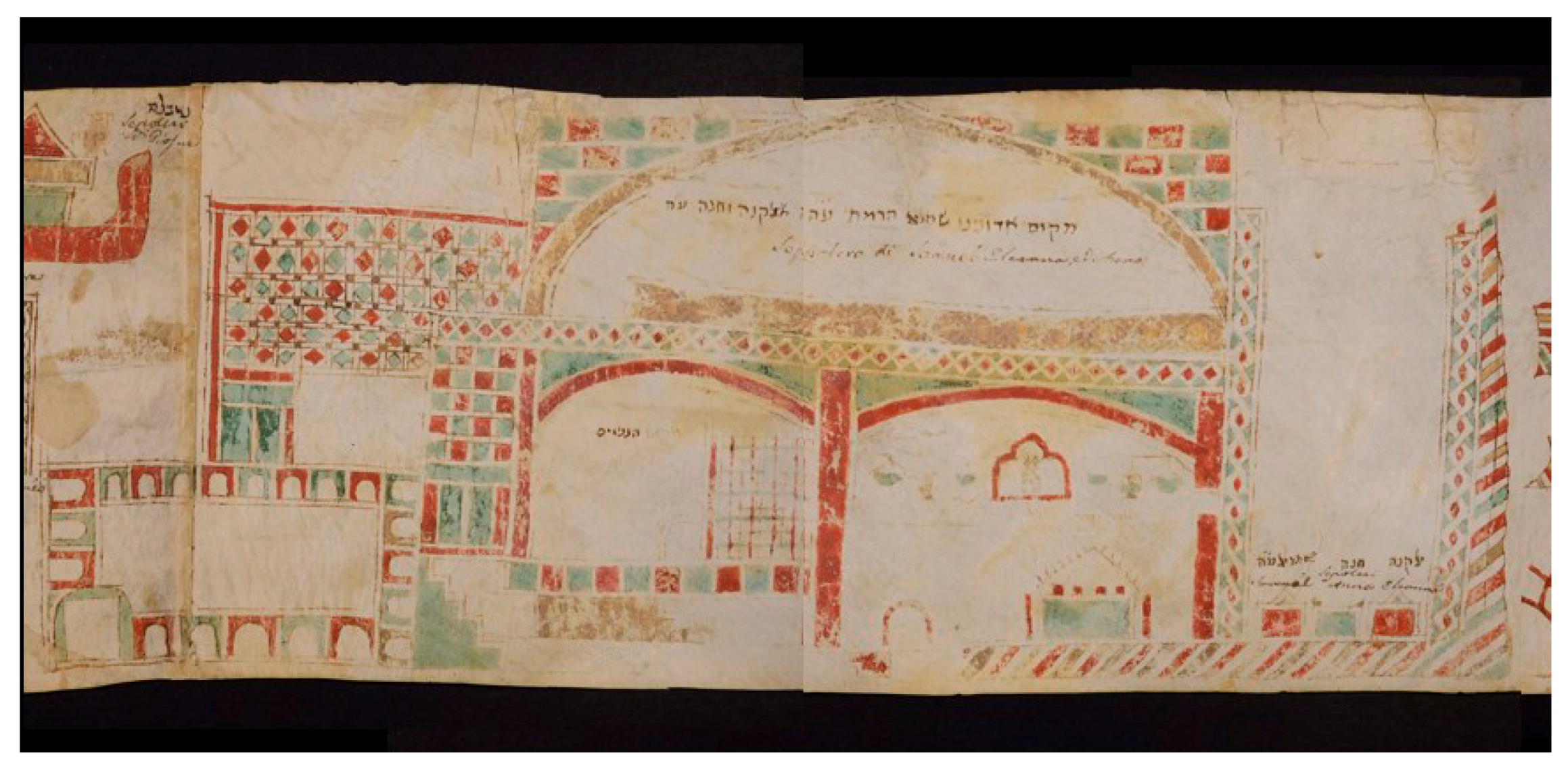

heiḥal in which the Torah scrolls were kept. An additional, similar image appears later in the scroll, in an illustration depicting the place of worship in the compound of the tomb of Samuel the prophet, known by its Arabic name Nebi Samwil, northwest of Jerusalem (

Figure 4).

Nebi Samwil is identified in Jewish tradition as biblical Ramah,

30 and from the thirteenth century, an important ceremony was held there as part of the annual

Ziyāra to the holy places in the Land of Israel.

31 According to historical information from the Mamluk period, Jews purchased the cave and established a synagogue and a large courtyard that was intended for the many pilgrims arriving during the period of the

Ziyāra. Testimonies about the existence of a synagogue are known from the mid-fifteenth century onwards,

32 although I. Ben-Zvi and Reiner argue that Jews owned the site as early as the end of the twelfth or beginning of the thirteenth century.

33 Some scholars believe that the synagogue was active until the sixteenth century,

34 while Ben Zvi argues that it continued to function until the beginning of the eighteenth century, despite repeated attempts to extricate it from the hands of the Jews. The visual depiction of the place of worship within the compound of Samuel’s tomb in Ramah in the Florence Scroll provides clear and tangible proof that a synagogue existed there as early as the beginning of the fourteenth century. In the framework of this article, I refer only to the elements connected to the depiction of the synagogue and not to the entire illustration of the compound.

35 At the center, under a large dome, appear two spaces with vaulted ceilings. In the right-hand space of the structure is a tombstone, and above it, the image of the niche containing a Torah scroll, under which appears the caption “

heiḥal”. In the left space is a kind of lattice of horizontal and vertical lines, beneath which is the caption “place of the women”.

36 It seems that the image of the niche of the

heiḥal, as depicted in illustrations of the compounds at both Dammūh and Ramah, was a conventional motif used by the painter of the Florence Scroll to designate a place of worship.

In addition to these two instances using the conventional motif of niches containing Torah scrolls in the illustrations of the synagogues in Dammūh and Ramah, we must examine a third important depiction. Using UV photography on the remains of the illustration preceding the depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā in the first part of the scroll, it is possible to discern another image of a Torah scroll in a heiḥal. Although it is unclear which holy site is depicted here, a number of possibilities will be discussed below. This image is unique in a number of respects: the Torah scroll is of larger dimensions and it is even possible to see the Torah finials that decorate its trees of life. This Torah scroll was clearly accorded significance: it is placed on a graded and raised pedestal, and the niche of the heiḥal is also large and decorated. Despite the similarities between this Torah scroll and the two small ones in Dammūh and Ramah, it is evident this was a Torah scroll of particular importance.

The Torah scrolls and bibles that were kept in synagogues in Egypt, Syria, and the Land of Israel were often perceived as holy objects, and they were venerated similarly to relics in churches, holy trees, or tombstones at holy sites. Worshippers regarded them as objects that mediated between God and the believer, attributing to them magical powers. In these communities, many legends and tales circulated regarding the miraculous origins and travels of these Torah scrolls, and there were common traditions concerning the early scribes that copied them.

37A number of sources from different periods mention a holy Torah scroll with magical powers, which, according to tradition, was written by Ezra the scribe and was kept in the Synagogue of Palestinians (=the Synagogue of

Yerushalmim) in the Coptic quarter of Fusṭāṭ. The scroll was kept in a high

heiḥal, far from the reach of human hands. Regarding this Torah scroll, al-Maqrīzī wrote in the fifteenth century: “In this synagogue there is a copy of the Torah, regarding which all agree that it was written by Ezra…”

38A similar depiction appears in a letter written by R. Obadiah of Bertinoro in 1488. He describes a Torah scroll that was kept in a high

heiḥal in the upper northeast corner of the synagogue. He also provides a detailed report of its theft and disappearance.

39 Sambari, writing in the seventeenth century, mentions that Ezra’s scroll was previously kept in a

heiḥal located in the upper corner next to the ceiling, and a curtain covered its opening.

40 The Synagogue of the Palestinians was one of the most central and important places of worship for the Jewish community of Fusṭāṭ-Cairo in the Medieval period. In later generations, it was named Ezra’s Synagogue, and it was there that the Cairo Geniza was found.

41Alternatively, it is possible that the remnant of the illustration depicts the synagogue that was located in al-Maḥallah in the Nile Delta. This too was a central holy site and a place of pilgrimage for the Jews of Egypt, and it too housed a venerated Torah scroll.

42The three depictions of Torah scrolls housed in a heiḥal in the Florence Scroll, both the two small ones and the larger image in the remnants of the first illustration, raise the question of why the Torah scroll is depicted in an open heiḥal, revealed to all. This appears to contradict the custom of keeping the Torah carefully guarded in the heiḥal, behind closed doors that are covered by a curtain (parochet). The opening of the doors and movement of the curtain, both in the past and today, constituted a precise segment of the prayer rite.

This depiction of an open

heiḥal brings to mind the well-known illustration of the synagogue in the Sarajevo Haggadah, which was apparently written in North Aragon, Spain, in the second quarter of the fourteenth century.

43 In this illustration too, a

heiḥal appears in a wall niche, as was customary in Spanish synagogues and those of the Mediterranean basin.

44 The scene in the illustration depicts the end of the prayer service. The worshippers are departing from the synagogue yet, nevertheless, the doors of the

heiḥal are wide open, and the Torah scrolls within it are visible to all. Various scholars have discussed the questions this illustration raises: why are the doors of the

heiḥal open, when the illustration depicts the end of the prayer service and the worshippers are turning their backs to the

heiḥal? And who is the figure behind the departing worshippers, stretching out their hand to the Torah Scrolls? Sabar suggests that the figure next to the open ark is a woman praying before the scrolls. He claims that the illustration depicts the custom, common among the communities of Spain, southern Italy, and the Jews of Islamic countries, and which existed until the modern period, that allowed women to enter the men’s section at the end of the prayer service and approach the Torah scrolls in the

heiḥal, enabling them to make personal pleas for health, fertility, marriage, livelihood, or any other request.

45 In addition to the custom of women’s prayers before the

heiḥal, Sabar also describes other special times, not part of the routine prayers, during which the

heiḥal was opened: for example, during the reading of prayers and Psalms for the wellbeing of a mother after the birth of her child. Another interesting custom was the placing of notes containing requests upon the case of the Torah scroll.

46The depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā in the List of Yitgaddal may also allude to the custom of women praying before the Torah scrolls. In the second, lower section of the illustration is a caption noting a certain place where women could see the Torah scroll.

47 A further interesting caption notes a specific location in which the scrolls were rolled up after their reading.

48 Although the first caption may indicate the women’s section,

49 in light of the custom of opening the

heiḥal to enable women to lay out their requests, we can suggest that it designates a certain place in which the women gathered to pray before the Torah scrolls. It should also be noted that in the illustration, this is located close to the place where the scrolls were rolled up. Considering that the scrolls were rolled up at the end of the Torah reading, it seems that after the rolling of the scrolls, either following a public ceremony during the

Ziyāra or at another time, pilgrims also were given an opportunity for personal prayer before the open

heiḥal.

Clear testimony regarding the custom of placing notes with personal requests inside the

heiḥal is found in a touching poem written by Moshe b. Shmuel of Safed. Ben Shmuel was a scribe—

Katib in the local language—who was forced by one of the rulers of Damascus to convert and serve as his personal scribe. Mann believes that the story related in the poem concerns the conversion that was forced upon the Jews of Egypt and Damascus in the Mamluk period, apparently at the end of the thirteenth century.

50 In his poem, Ben Shmuel relates how he was forced to make a

Haj journey, together with his master. Upon returning to Damascus, he visited the Synagogue of the Prophet Elijah in the village of Jobar, close to the city. He entered the cave which one accesses via the synagogue, and in which, according to tradition, Elijah hid during his flight from Jezebel.

51 There, he approached God with an emotional prayer, placing in the ark a letter begging God to save him from the forced conversion and from making another journey with his master:

I entered the Synagogue of the Prophet Elijah. I prayed before Him [God] in the Cave of Hiding… I placed the letter in the Ark and prayed before God as much as I could.

52

The status of Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar among the Jews of Syria in the Medieval period, and until its destruction in 2014, was similar to that of Kanīsat Mūsā among the Jewish community of Egypt, as will be discussed further below. Here, we relate only to a testimony concerning the custom of personal prayer before the open heiḥal and the custom of placing notes inside it, which recalls a similar custom mentioned by Sabar.

The depiction of the Torah scrolls in the open heiḥal, as in the illustrations in the Florence Scroll, was apparently used as a symbol designating a place of prayer, in particular, in the depiction of the places of worship in Dammūh and Ramah. Yet, it is reasonable to assume that this symbol was consolidated as a result of the pilgrimage and prayer customs practiced in the synagogues located at central holy sites.

The detailed and elaborate illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh in the Florence Scroll is the earliest known depiction of the site. An analysis of the illustrations depicting it in that scroll and in the List of Yitgaddal is instructive concerning its true appearance: the prayers in the open courtyard in the summer, the location of the well, and the existence of the secondary holy spaces dedicated to other biblical figures aside from Moses, the central personage associated with the site. Likewise, we find in them information about the site’s internal contents and its various functional elements. Furthermore, I propose that we can also learn about the custom of personal prayer in front of the open heiḥal and the Torah scrolls it housed. These two depictions are apparently firsthand eyewitness testimonies by members of the community, who, like all other members, made pilgrimages to Dammūh and participated in the public ceremonies and prayers conducted there at various times throughout the year.

4. Between Reality and Symbolism

An examination of other holy places depicted in the Florence Scroll reveals that the illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā is exceptional, particularly in comparison to the other large illustrations portraying central holy sites, such as the Cave of Makhpela (

Figure 5) or the Temple on the Temple Mount (

Figure 6). These illustrations are based on formulaic models that were almost certainly part of a local visual tradition. They present the various sites through fixed visual motifs that recur in various ways in each one of the illustrations. Thus, for example, the façade of many of the structures is made up of a series of arches, and at the center of each arch is an oil lamp. Strips of guilloche divide up horizontally the various structures, many of which have an onion dome, without any connection to their real appearance. These formulaic models sometimes integrate realistic components of the sites they represent, suggesting that the models at the disposal of the painter, and which were copied into the scroll, were specific models based on real sites. The illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā and of Samuel’s tomb in Ramah were drawn in freehand by the scroll’s painter, without relying on a copied model. For this reason, the illustrations seem ostensibly simple and modest in relation to the remainder of the illustrations, which are of higher aesthetic quality and rich in decorative motifs. Considering this, we can suggest that the decision to draw Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh and the tomb of Samuel in Ramah freehand derived from the status of these two places, which were among the most important on the route of the

Ziyāra. Copying an existing model would not allow the painter to present a detailed and realistic illustration of these sites and their contents.

53Despite the similar way in which Dammūh and Ramah are depicted, the illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh is unique in that it provides two visual perspectives: a general, bird’s eye view and the elements of the façade from a horizontal perspective. This same unique depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā recurs in the List of Yitgaddal. Here too, apart from Kanīsat Mūsā, the remainder of the sites are depicted in an accepted and familiar manner, from a horizontal perspective, portraying the structures’ façades.

Parallel architectural depictions, presenting both a general overview of a holy place from above and the internal space and objects inside it from a horizontal perspective, existed in the Muslim geocultural artistic surroundings in which the illustrations of Kanīsat Mūsā were painted. We find examples of this in illustrations of various holy sites, principally the compound of the Kabba in Mecca.

54 Similar Muslim images of the Temple Mount are also known from the beginning of the sixteenth century onwards. Milstein highlights the Islamic perception connecting the two holy cities, according to which the two cities are regarded at once as earthly sites in which real historical events took place and heavenly places close to the Garden of Eden.

The combination of an architectural depiction from above and internal details from a horizontal perspective is rooted in a longstanding Jewish artistic tradition used to depict the sanctuary (

mishkan) and Temple.

55 We find this combination in depictions of the Temple or sanctuary on the opening pages of manuscripts of bibles from Egypt and the Land of Israel from the ninth and eleventh centuries, both those of rabbinic Jews and Karaites.

56 The earliest example is the first Leningrad bible from Fusṭāṭ, dated to 929.

57 Today, we also know of two exceptional illustrations in bibles from Spain that provide an architectural view of the structure of the Temple from above and a depiction of the holy objects and internal architectural elements from a horizontal perspective. One is the Ibn Merwas bible from 1300,

58 and the other was drawn by Joshua Ibn Gaon in Soria, Spain, in 1306.

59 Both Bezalel Narkiss and Katherine Kogman-Appel suggest that the way in which the sanctuary or Temple is depicted from above, or from a bird’s eye perspective, is a methodological means of enabling the artist to depict the internal space and its internal elements in an informative and methodological manner.

60Jews in the communities of the Middle East and Spain refer to the Bible as “

Mikdashya” because it is perceived as inheriting the holiness of the destroyed Temple, similarly to the synagogue, which is known as “

Mikdash me’at.” Scholars agree that the illustrations of the Temple in bibles from the Near East or Spain, whether this includes an architectural representation or the depiction of the holy vessels alone, were intended to impart this meaning.

61 They can also be viewed as an expression of the longing for redemption and the rebuilding of the Temple.

62The Jews of Egypt regarded Kanīsat Mūsā as a holy site that inherited the sanctity of the Temple. Indeed, some made pilgrimages to this site rather than embarking on the lengthy

Ziyāra pilgrimage to Jerusalem, as al-Maqrīzī notes.

63 Considering the artistic traditions from Spain and the Near East, we must ask whether the depiction of Kanīsat Mūsā from two perspectives in the Florence Scroll and the List of Yitgaddal is merely a means to offer an informative and realistic depiction of the place or bears some symbolic significance. The various illustrations of the sanctuary, the Temple in Jerusalem, the Holy Mount, and the Kabba in Mecca seem to suggest the existence of a visual convention regarding the presentation of places imbued with great sanctity, places that were viewed as inheriting the holiness of the destroyed Temple in Jerusalem, and perhaps also, the earthly counterpart of a heavenly place.

The depiction of the holy site at Dammūh using this visual convention, which in all likelihood designates it as possessing a similar status to the Temple, connects to another important element in the comprehensive and detailed illustration in the Florence Scroll: around the wall enclosing the compound is a river (

Figure 1). Similarly to the supernatural form of the holy tree, so too the appearance of this river is not realistic: it begins in the upper margins of the scroll on one side of Kanīsat Mūsā, goes around the frame enclosing the compound on three sides, and rises up and disappears into the upper margins on the other side. It is impossible to know whether the river completed a full circuit because today, the upper margins of the scroll are cut off. The depiction of the river is accompanied by a caption identifying it as a river associated with Egypt and the Garden of Eden.

64 It seems to refer to the Nile, also called “the river of Egypt”. The belief that the Nile was one of the four rivers flowing from the Garden of Eden was a local tradition known from the Hellenistic–Roman period.

65In the Medieval period, the source of the Nile was shrouded in mystery and various theories were posited. Apart from the common belief that its source was in the Garden of Eden, there was also another theory, according to which it flowed out from the Mountain of the Moon in Africa.

66 The maps made by Islamic cartographers from the eleventh century until the end of the Medieval period, in which the Nile is depicted twisting at straight angles, similarly to the way it appears in the Florence Scroll, also drew on this theory.

67 The chronicles by al-Maqrīzī and Joseph Sambari describe a third theory, combining the two earlier ones, according to which the Mountain of the Moon in Africa is in fact the Garden of Eden.

68 Apparently, both the belief that the source of the Nile was in the Garden of Eden and the image of the Nile turning at straight angles in Medieval maps informed the design of the river associated with the Garden of Eden that encircles the frame of Kanīsat Mūsā here.

There also appears to be a further explanation for the image of the river around Kanīsat Mūsā and its source in the Garden of Eden: in the Middle East, holy sites and tombs of saints to which Muslims, Christians, and Jews made pilgrimages were often located in rural areas. They were places of peace and calm, cut off from daily life and from the crowded, noisy cities, in enclosed compounds containing water sources, orchards, groves, and agricultural areas. The worshippers in these places felt that they were in the Garden of Eden, at least in the sense of an orchard.

69 According to local beliefs, the holy people with whom such sites were associated resided at once in the earthly holy site and in the heavens.

70 5. Synagogues in Illustrated Scrolls of Holy Places from the Sixteenth Century

The Florence Scroll and the List of Yitgaddal are both considered harbingers of the artistic genre devoted to visual depictions of holy sites and constitute its earliest paradigms. They are distinguished from later manuscripts by their unique character. Each of them was drawn by the hand of an illustrator who created a visual depiction of the holy places, perhaps an expression of his own pilgrimage. Over the years, the portrayal of the holy sites consolidated into an artistic tradition that employed formulaic motifs. This artistic tradition characterizes a corpus of sixteenth century manuscripts on parchment scrolls rolled from top to bottom, significantly smaller than the Florence Scroll.

71 All the scrolls of the corpus contain, albeit with small changes, a copy of the work

Yihus ha-Avot, which was apparently composed in Jerusalem at the end of the fifteenth century.

72 The illustrations of the holy sites appearing therein were intended to help emissaries from the Land of Israel who set out for the diaspora to collect donations, and these illustrated scrolls aided them in describing the holy sites guarded by the Jews living in the Land of Israel, in which they prayed for their brothers in the diaspora. It is likely that they were also a gift given to important donors. In light of their representational aim, the scrolls were copied by professional scribes and illustrators in Jerusalem and Safed. Some of the scrolls were copied and illustrated in Italy, apparently because emissaries from the Land of Israel stopped there on their way abroad or on their return. In the manuscripts known today, it is possible to identify two main styles of illustrations,

73 one reflecting the style of architectural images from the Middle East, as seen in the scroll from the Land of Israel (

Figure 7),

74 and the other characteristic of Italian architectural representations, evident in the scroll copied in Italy (

Figure 8).

75Despite this stylistic difference, a common schematic artistic approach is evident in both: all the scrolls employ similar visual motifs to represent certain types of structure. Thus, for example, in the scroll from the Land of Israel, the architectural image that recurs with minor differences is a kind of frame, housing an internal space containing an arch with an oil lamp at its center, and sometimes, tombstones and burning wax candles. These motifs appear in a more complex manner in the depiction of important and large structures. The illustration style in the Italian scroll reflects the architectural characteristics of the Italian Renaissance, expressed in motifs such as columns with capitals, gables, and domes. Sometimes, the grave of a saint is represented by the image of a sarcophagus. Many of the illustrations present a cylindrical structure with a dome, recalling the Tempietto in Rome. Akin to the similar visual patterns that depict different types of holy places and graves of saints, it is possible to identify in the corpus of sixteenth century manuscripts a common visual representation designating synagogues. In the illustrations from the Land of Israel, this is the image of a relatively large structure on two levels, containing internal arches and many oil lamps. In the internal space is a platform on which the Torah scrolls are placed. In the images from Italy, the synagogues are depicted using a visual representation that recalls a classical shrine. The façade contains a series of columns with capitals supporting a dominant gable roof. In the internal space are platforms upon which Torah scrolls were placed, and sometimes, we even see an open scroll on a table. Synagogues merit a prominent depiction of large dimensions, both in the manuscripts from the Land of Israel and those from Italy. In the framework of this article, it is not possible to expand upon this matter and we cannot explain the surprising way in which the Torah scrolls are depicted on the reading stand or platform rather than within the ark. However, this may have been intended to express visually the synagogue’s pride regarding the number of Torah scrolls it owned, similar to the textual descriptions in most of the works of this literary genre from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

On the background of this conventional depiction of holy places in the corpus of sixteenth century manuscripts and the appearance of a similar architectural pattern representing synagogues therein, we find an exceptional image. The image in question appears in a manuscript from the Land of Israel with an estimated terminus ante quem of 1538.

76 It depicts the Synagogue of Elijah in the village of Jobar, close to Damascus (

Figure 9). Similarly to the appearance of Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh in the Florence Scroll and the List of Yitgaddal, this image too offers a general overview from above rather than the horizontal perspectives found in the rest of the manuscript’s illustrations.

6. Elijah’s Synagogue and the Cave in Jobar

Elijah’s Synagogue stood for hundreds of years in the village of Jobar, which lay three kilometers northeast of Damascus. Today, Jobar is part of the city center and the synagogue was destroyed in 2014 by bombing during the civil war.

77 The synagogue was part of the holy site and a place of pilgrimage visited by Jews from Syria and the surroundings, and inside the compound were gardens, vineyards, and fields. As was noted, according to its foundational myth, Elijah hid in the cave within the synagogue, and one could see the hole through which, so tradition relates, the raven brought him bread and meat.

78 In addition to this foundational myth, other traditions regarding the place are mentioned in travelers’ accounts: within the synagogue stood a marble stone enclosed with a grate, and according to various versions, Elijah anointed on it Hazael as king of Aram, or, as a later tradition relates, Elisha to succeed him as prophet.

79 Other traditions concern the renewal of the synagogue, or the construction of an additional structure, by the Tanna (sage) Elazar ben Arakh.

Historical scholarship dates the site to the Byzantine period, and most scholars agree that it was built before the Islamic conquest.

80 The Jews of Damascus made pilgrimages to the synagogue for personal prayer or for public prayers on Sabbath eves and other occasions. Magical and healing properties were attributed to the cave of Elijah, and the sick would sleep there overnight as a cure for their illness.

As was noted, in the scroll of holy places originating from the Land of Israel, Elijah’s Synagogue at Jobar is represented by means of a bird’s eye view, a kind of floor plan. The image consists of a rectangular frame, in the bottom part of which appear three openings with internal arches and oil lamps. The space of the openings contains a caption identifying the image as the synagogue associated with the prophet Elijah.

81 The central area is divided into two parts, one of which is narrow, containing images of oil lamps. An additional line of oil lamps appears in the lower part of the wide, central section, and there are six columns on each side, accompanied by a caption stating they are marble.

82 In the uppermost part of the central space are two bases, a pair of Torah scrolls on each, and between them hangs an oil lamp. The caption indicates that this is the

heiḥal.

In contrast to Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh, which was destroyed prior to the seventeenth century, there are many photographic and written testimonies regarding Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar, including sources from the modern period. The literature written by travelers in the Medieval and Early Modern periods, as well as modern day stories told by members of the community and scholars, indicate that it was a place of impressive beauty. The depictions detail the light of the colored oil lamps, the rugs that covered the floor, and the

parochot (curtains) that hung on its walls.

83 The synagogue, a basilica structure in which marble columns separated the two wings from the central section, was around 32 m long, 13 m wide, and the entire area totaled approximately 400 square meters.

84 Stone benches ran along the walls, on which the worshippers sat. The

heiḥal was located on the southern wall, as was customary in Syrian synagogues. Next to it, to the west, was an opening from which a twisting flight of steps led to the cave in which, according to the tradition, Elijah hid. In the central section stood the

teiva, and indeed, there was a stone encircled by grating, on which, according to various traditions, Elijah anointed either Hazael or Elisha.

The visual representation in the scroll from the Land of Israel lacks most of the important holy focal points of the site (

Figure 9): there is no representation of Elijah’s cave or the stone on which he anointed Hazael/Elisha. This is instructive regarding the nature of the depiction—before us is a schematic and conventional depiction rather than a realistic and specific portrait of the site. Similarly to the unique illustration of Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh in manuscripts dating from two hundred years previously, the Florence Scroll and the list of Yitgaddal, here, only the illustration of Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar combines two different visual perspectives.

7. Dammūh and Jobar: Between the Temple, the Sanctuary, and the Garden of Eden

Jews in Egypt, Syria, Babylon, and Persia made pilgrimages to major holy sites in their close surroundings. They visited these territorial sites—as Reiner defines them—for purposes of personal prayer or as part of public and communal rituals held at fixed times of the year. Sometimes, due to various circumstances, the popularity of these territorial holy sites spread beyond their direct geographical surroundings, and they were frequented by pilgrims from neighboring countries and far away. Their boundary-breaking status is evident in the literary accounts written by pilgrims who embarked on lengthy journeys to visit them.

85 Both Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh and Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar are examples of territorial holy sites that were frequented by pilgrims from distant lands.

The territorial holy sites were entrusted to the supervision of the communal leadership in the closest major city. Kanīsat Mūsā was under the supervision of the communal leadership of Fusṭāṭ-Cairo and for many years, was overseen by descendants of Maimonides. Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar was under the supervision of the Damascus community. These sites and the agricultural lands around them had the legal status of

heqdesh—public property managed by trustees. A similar legal status exists in the Islamic world—the

waqf. The financial profits from the harvest of the agricultural lands or from donations or legacies were earmarked for charitable purposes, such as supporting poor members of the community or the upkeep of the place and its protection.

86Some of the territorial holy sites were considered shrines that inherited the holiness of the Temple in Jerusalem. The sages interpreted the term

mikdash me’at, mentioned in God’s words to the prophet Ezekiel,

87 as referring to synagogues and study houses in Babylon, some of which were considered places of the utmost sanctity and holy sites to which the divine presence (

shechina) wandered following the destruction of the Temple.

88 The sages mention, in this regard, sites in Babylon such as the synagogue of the house of Benjamin between Nehardea and Sura,

89 and the synagogue in Nehardea.

90 Beginning in the mid-ninth century, Knesset Ezekiel also came to be known as an additional territorial holy site, later assuming a central role and surpassing its predecessors in Babylon in terms of importance.

91 A similar tradition identifies places in Egypt, Syria, and the Land of Israel to which the divine presence wandered after the destruction of the Temple. In his article, H. Schwarzbaum discusses at length the status of the synagogue in Jobar, and the fact that it was constructed miraculously, not by the work of man.

92Various religions conducted similar, sometimes even common, public, and personal rituals in holy sites. Many of the characteristics of these rituals resulted from the continuous development of the Christian cult in holy sites in the Mediterranean basin between the third and sixth centuries. In the first centuries of the Common Era, and in the Mamluk period discussed herein, celebrations at these sites often involved breaking the conventional divisions of social status, as well as the rules of modesty and the separation of the sexes. Islamic and Jewish religious decisors repeatedly established regulations to maintain the rules of modesty in accordance with the socioreligious conventions that were observed punctiliously outside the compounds of these holy places.

93The annual celebrations marked events connected to the life of the figure with whom the site was associated. In Egypt and Syria, many synagogues and holy places were linked to Moses and the prophet Elijah, and various events in their lives as related in the Bible and Midrashic literature.

94 The figures of Moses and Elijah possess similar characteristics: they both represent the redemption and the liberation from the yoke of foreign peoples, both experienced divine revelation on Mt. Sinai, and according to common belief, both did not die a natural death but rose up to the heavens. Although the biblical story depicts only the ascent of the prophet Elijah, due to the lack of information regarding Moses’ burial place, tradition relates that he too ascended to the heavens and in the future, will be revealed anew.

95Pilgrims customarily visited Kanīsat Mūsā at the festival of

Shavuot, the time at which Moses received the Tablets of the Law on Mt. Sinai and, according to common belief, the time of his first ascent to heaven. Another gathering occurred on Adar 7 and 8.

96 According to tradition, Moses was born and died on Adar 7 (although his death was perceived as supernatural and in fact, denoted his second ascent to heaven). The pilgrims fasted on Adar 7 and, on the following day, held celebrations. Maimonides, who was personally involved in overseeing Kanīsat Mūsā, notes that these celebrations were intended to mark Moses’ ascent to eternal life in the Garden of Eden.

97The pilgrims to Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh, or to the synagogue of Elijah in Jobar, entered a site enclosed by a wall that defined the physical boundaries of the place. However, this wall simultaneously defined the conscious boundaries of a liminal holy place, located between heaven and earth. The holy figures to whom the place was dedicated, Moses and Elijah, reside in the Garden of Eden, similarly to the Christian and Muslim belief regarding Jesus and Muhammed ascending to heaven and their resurrection at the end of days.

98 A pilgrim who visited these sites for personal or public prayer addressed his prayers to Moses or Elijah, who were at once present in the earthly holy site and the Garden of Eden in heaven.

In this article, I suggest that the visual convention used to depict Kanīsat Mūsā in the Florence Scroll and the List of Yitgaddal symbolizes a place that is simultaneously a kind of heavenly Garden of Eden and a

mikdash me’at, perpetuating the past holiness of the sanctuary and the Temple in Jerusalem.

99 Perhaps, it was even (one of) the place(s) to which the divine presence wandered after the destruction of the Temple. In all likelihood, other scrolls from the fourteenth and fifteenth century that have not survived contained similar depictions of this convention, and perhaps such a convention was also used in the Medieval period to represent other holy places with similar status.

The images of Elijah’s Synagogue discussed herein appear in a scroll from the Land of Israel that is the earliest in the corpus of sixteenth century scrolls known today. My study has demonstrated that this scroll served as a master for later manuscripts.

100 Regarding the unique appearance of the synagogue of Elijah in Jobar in this scroll, we must ask whether the illustrator of the scroll copied the convention innocently or was aware of the entire range of the possible meanings suggested herein.

The paucity of findings dating from the years between the beginning of the fourteenth century and the beginning of the sixteenth century prevents us from determining with any certainty whether the visual convention maintained its meaning over the years. We can suggest that this meaning was indeed known in the sixteenth century, on the basis of an analysis of later depictions of Jobar and Dammūh in sixteenth century scrolls, and an examination of the historical background.

In the early scroll from the Land of Israel, as in the remainder of the corpus, Kanīsat Mūsā in Dammūh is represented from a horizontal perspective, similarly to the other illustrations in the scroll (see the last image below in the scrolls in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8 ). Pilgrimages to Dammūh declined during the sixteenth century and the site gradually lost its status, until it was completely destroyed close to the turn of the seventeenth century.

101 In contrast to this historical process, Elijah’s Synagogue in Jobar not only maintained its status as a central and territorial holy site of the Jews of Damascus and the surrounding areas, but historical circumstances even increased its importance. In the sixteenth century, during which exiles from Spain arrived in Syria, some of the most prominent and spiritual and religious figures in Israel, Egypt, and Syria gathered there at various periods. Rabbi Yaakov Berab (1474–1541), known for renewing ordination in Safed, spent time in Jobar. Likewise, the kabbalist Rabbi Hayim Vital (1542–1620) and his student Rabbi Shmuel Abuhatzera moved from Safed to Jobar. Abuhatzera was known as one of the permanent residents of the place and upon his death, was buried in the synagogue’s courtyard. The well-known poet and commentator, Rabbi Israel Najara (1555–1628), lived in Jobar for some time.

102 In his chronicle, seventeenth century writer Yosef Sambari describes these figures and the miracles that took place there.

103Considering the far more central role played by the synagogue in Jobar during the sixteenth century, we can suggest the possibility that its appearance in the early scroll is not coincidental. Rather, this was intended to express the entirety of the meanings raised here. In the other scrolls of the corpus, all later, and in the remainder of illustrations depicting holy sites from the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, we do not find this visual convention, perhaps because another artistic tradition replaced this earlier artistic custom, which dates to the fourteenth century.