1. Introduction

Being called up to the Torah is considered a special honor, as are other activities performed around the Torah scroll. In some historical periods and in certain regions and communities, it became the custom to auction the honors received around the Torah, and in others, to offer a charitable donation as an expression of gratitude for them. This latter is often done in the framework of the Misheberakh (‘May He, who blesses’) prayer recited on behalf of the person called up to the Torah. In Hungarian Jewish usage, there is a term for this specific type of charitable donation: snóderolni (‘to donate’) and snóder (‘donation’)—which is derived from the Yiddish shnodern, and in Yiddish from a phrase in that Mi she-berakh (pronounced also fused: misheberakh) prayer: she-noder, ‘one who donates’. The present article looks at two types of objects used in synagogues related to this type of charity.

As opposed to many other Judaica, these two types of objects do not have names in common or in scholarly usage—we will use the terms ‘shnoder-sign’ and ‘shnoder-book’ for them. By ‘shnoder-signs’ we mean permanent structures, affixed to the bimah, which contain signs that refer to this act of charity connected to the reading of the Torah. In the interwar years, the Hungarian term adománytábla (donation sign) occasionally appears in certain communal regulations, probably referring to such shnoder-signs, but this term seems to have been more ephemeral than the objects themselves.It did not appear in any other context or period in Hungarian, and there is definitely no equivalent to it either in English or in Hebrew. We use the term ‘shnoder-book’ for objects that served to record these charity offerings, whether they had the actual form of a book or not. We have not found ‘shnoder-signs’ or the description of similar items anywhere in scholarly literature. In contrast, ‘shnoder-books’ do appear in some museum or auction catalogs, in archival inventories or bibliographies, but by a variety of names: ‘deposit-book of pledges’, ‘offertory book’, ‘donation deposit book’, ‘ledger of pledges’, ‘community ledger’. The lack of a common name for these objects is in part due to the ephemeral nature of their use. Benefactors as well as recipients of charitable donations are subject to regular change.

The ephemeral use of these objects also explains why they are not among the widely known items in Judaica collections. Their material and design were typically less elaborate and less durable, and they were thus less likely to be considered collectibles. Some shnoder-books did get preserved, mainly ones in book form, which, as archival material, had a similar fate as communal records and pinkasim (minute books). One can assume, though, that many others, and especially those that used less permanent solutions to the problem of recording donations, were lost and forgotten. In the case of signs affixed to the bimah, several have survived, but there are even more cases where their existence (or the lack of it) can be seen in archival photos only, as the synagogue interiors, if not the synagogues themselves, were destroyed during the Second World War or thereafter. The perspective and quality of the photos often make it impossible to discern the exact description on the signs themselves.

Due to the limited number of objects available, our current paper does not aim to give an overall picture of these items. This paper introduces them to the research of synagogue objects and rituals and promotes the preservation of these objects in situ or in museum collections. Besides describing the various possible forms of these objects, we look at the historical and Jewish religious considerations that led to their development and defined their use. Since there is no unified terminology, these are probably more informative for readers than descriptions and can form the basis of further research looking at the art historical aspects of these works.

Our research focuses on the objects surviving in synagogues or found in archival photographs from the Hungarian Lands. The largest collection of photos of synagogue interiors in historical Hungary is available online in the Hungarian Jewish Museum and Archives.

1 Moreover, to double-check our findings and to perform comparative analyses, we tried to collect data from a wider geographic region. Apart from the literature on synagogues, we researched the photoarchives of five larger collections: The Center for Jewish Art, Jerusalem; the Museum of Jewish People at Beit Hatefutsot Museum, Tel Aviv; the Jewish Museum in Prague; YIVO Archives and Library Collections and the Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam.

2. Fixtures and Signs on the Bimah

In the

Shulḥan Arukh,

2 there is a comment regarding the recital of the

Shema Yisrael prayer according to which “things that are written should not be recited by heart.”

3 By its literal meaning, this refers to Biblical texts, but it is often applied to prayers and blessings as well, especially in the case of those blessings that are recited in public, and that might not be known by heart by every member of the community, in order not to humiliate them. Among the blessings recited by laypeople in public are the ones of the Torah-reading: The person called up to the Torah has to recite a blessing before and after the reading of his portion. There is a gloss of Moses Isserles

4 to the rules of the blessings for the Torah reading in the

Shulḥan Arukh,

5 according to which the person called up to the Torah should look to the side while reciting the blessings, to show that they are not written in the Torah. This rule is further elaborated on by the

Magen Avraham.

6 It was recorded about Ezekiel Landau

7 that for the blessings of the Torah reading, he always had the sign with the blessings in front of him in order not to humiliate those who did not know it by heart.

8 And there is a similar tradition known regarding the Ḥatam Sofer as well.

9Having the blessings ready on the bimah seems to be a practical solution for fulfilling these rulings. It is, indeed, common in many synagogues around the world to use a separate sheet of paper or a piece of cardboard with these blessings written on it—but these are mobile and ephemeral objects which would only rarely enter Judaica collections.

The authority of Isserles and the

Magen Avraham on religious law and ritual practice in the Ashkenazi world in general, and especially the influence of Ezekiel Landau and the Ḥatam Sofer in Central Europe, might explain the fact that it is in this region that such signs eventually came to be affixed to the

bimah, and so

bimah-signs with the blessings became common synagogue fixtures here and not elsewhere. They are common mainly in the broader territory of the former Austro-Hungarian Monarchy, including also regions somewhat further to the east, like the historical territory of Moldova. There are examples of such fixtures from Iași (Romania) to Prague (the Czech Republic), from Beregszász (Берегoве, Ukraine) to Eisenstadt (Austria), from Cracow (Kraków, Poland) to Bezdán (Бездан, Serbia). They were, however, not common either further to the west, in German territories,

10 or to the northeast (

Kravtsov and Levin 2017).

There are some examples for signs affixed to the

bimah also in historical Volhynia, for example in Dubno (Ду́бнo, Ukraine) and in Kremenets (Кременець, Ukraine), but instead of the text of the blessings, these signs contain a Biblical quotation reminding the person at the Torah of the custom of donating to charity, and especially fulfilling one’s charitable commitments: “It is better that you should not vow than that you should vow and not pay” (Eccles. 5:4).

11 So these signs are not related to the ritual of Torah reading, but to the custom of donating to charity in relation to it.

In the territory of historical Hungary (current Hungary, Slovakia, certain communities of Western Ukraine, Romania, Northern Serbia and Northern Croatia), the fixtures on the

bimah with the blessings of the Torah reading are especially interesting.They very often not only contain the blessings, but also call attention to the custom of charitable donations by naming various societies, organizations, or traditional charitable causes—those which were the suggested recipients of the shnoder-donations in that specific community. Outside of historical Hungary, such shnoder-signs are extremely rare, even in territories where fixtures with the blessings would otherwise have been common. Some of the exceptions include the synagogue in Vatra Dornei (Romania),

12 the Jeruzalémská synagogue in Prague (Czech Republic), and the synagogue in Rychnov nad Kněžnou (Czech Republic).

13On some of the shnoder-signs, there is another type of charity-related inscription. As in the case of other synagogue furniture and objects, the shnoder-signs themselves were typically donations too, and there often is an inscription on them—just like on a

parokhet (curtain that covers the Torah Ark) or a

ner tamid (eternal light)—with the donor, the manufacturer, the date of the donation, or the person in whose memory the object was donated. The inscription can be in Hebrew, in Hungarian, or both. For example, the wooden frame of the shnoder-sign that entered the collection of the Hungarian Jewish Museum as a donation of the Jewish community of Bezdan names the donor and the manufacturer.

14 The elaborately decorated cast iron shnoder-sign in the Kazinczy street Orthodox synagogue in Budapest gives the name of the manufacturer and the date as 1921, in Hebrew. In the offices of the Budapest Jewish Community’s rabbinate, there is a wooden shnoder-sign—unfortunately, of unknown provenance—with an inscription that includes the name of the donor in Hebrew, the family members in whose memory it was donated in Hungarian: “in memory of the members of the Klár, Kleinmann, and Szinaj families, who died martyr death in 1944–1945”, and the date of donation as 1949 (

Figure 1).

15The shnoder-signs are particularly interesting because they seem to be unique to the area of historical Hungary, and because the various possible charitable causes on them provide an insight into community life at the given place and time.

4. Charitable Causes on Shnoder-Signs

There is diversity among communities and synagogues in the number and combination of charitable causes offered on the shnoder-signs. The number of suggested causes varies from three (typically in smaller communities on the countryside) to 20 in certain synagogues in Budapest (e.g., Hegedűs street) (

Figure 6). The most common causes are traditional charitable funds, community organizations, and employees:

Tzedakah (charity, here in the sense of general charity),

Ḥevra Kadisha (burial society),

Talmud Torah (educational system), the women’s association, prayer leaders, hospitals. In accordance with general practice, there were often actual associations behind these charitable funds. In these cases, these associations had their own budgets, funds for which were collected through membership fees, regular fundraising events, occasional donations, and contributions, and each association could raise funds in accordance with its own internal regulations. If an association had its own synagogue or prayer services, the shnoder-money in that synagogue obviously went to the association itself. There was no need for a shnoder-sign. However, in community synagogues, with several possible charitable causes and related associations, the rights and opportunities of a specific association to raise funds were typically regulated by the community’s leadership in the community’s statutes.

Based on a verse in the Torah (Deut. 15:11), rabbinic literature attempts to give general guidelines regarding the preferred order of charitable donations—such as the precedence of one’s relatives over others, of the poor in one’s city over the poor elsewhere, etc.

21However, these rulings cannot always be applied to the specific charitable organizations in every community. The inscriptions on the shnoder-signs, the choice, as well as their physical appearance and order, thus reflect the community’s preferences and changes therein—as can be seen in the following two examples: The old synagogue of Szeged and the Status Quo Ante synagogue of Debrecen.

In the old synagogue of Szeged (built in 1843), the shnoder-sign is known from archival photos only.

22 On it, one can see the blessings inscribed in marble, and above them, in the same marble sign, there are six charitable causes listed in two columns, in the following order:

Ẓedakah, Ḥevra Kadisha, Talmud Torah, Aniyei Irenu (the poor of our city),

Hakhnasat Kalah (providing dowries for poor brides),and

Parokhet (

Figure 7).

The

Ḥevra Kadisha of Szeged was founded in 1787, two years after the community itself (

Löw and Klein 1887, p. 19). Its prominent place on the shnoder-sign, right after general charity, is not only due to its being the oldest association in the city but also to the fact that it was the most important one in Jewish religious and communal life. The specific rights of the

Ḥevra Kadisha in the synagogue changed over time, but its right to collect funds during Torah reading always remained guaranteed by community statutes. The

Aniyei Irenu was a local charity fund founded by the community leadership in 1837, before this synagogue was built. In the previous synagogue, the statutes allowed the use of a mobile charity box and made it possible that “donations be made for this purpose on the occasion of the Torah reading” (

Löw and Kulinyi 1885, p. 260). The

Hakhnasat Kalah fund was established in 1865 to support the marriage of girls in poverty, and it became one of the approved charitable causes in the synagogue that year. However, not all associations automatically became possible options for synagogue donations. The women’s association of Szeged, for example, was established in 1835, before the

Aniyei Irenu or the

Hakhnasat Kalah funds, but it did not become one of the possible charitable causes during Torah reading until the 1870s.Therefore, its name was not inscribed in the marble (ibid, pp. 302, 309). It does, however, appear as one of two other charitable causes, which were added to the wooden frame of the shnoder-sign, which is most probably younger than the marble shoder-sign itself. However, the

Bikur Ḥolim association (for visiting and helping the sick), which was established even earlier, in 1821, did not even make it onto the wooden frame (ibid, p. 260). The second cause mentioned on the frame is the construction of a new synagogue building—which clearly shows that the community leaders gave priority to raising funds for a larger building for the fast-growing community. The appearance of certain charitable causes on the shnoder-sign in Szeged, and especially their order, thus reflect the date when the specific funds were established and the time when they became recognized by the community.

There are other cases, similar to that of the building of a new synagogue in Szeged, where temporary local charitable causes appear on the shnoder-sign, for example, the building of a new mikvah (ritual bath) in Nagyszeben (Sibiu, Romania), or the writing of a new Torah scroll in Nyíregyháza.

The shnoder-sign in the Status Quo Ante synagogue of Debrecen (1910) has an ornate metal arch with a sign in the middle with the blessings, and underneath the blessings is a metal frame with nine slots and separate plaques in each slot with various possible beneficiaries. The plaques visible now are in Hebrew and/or Hungarian. They have been made in various designs, which suggests that they were not made at the same time. The plaque for the

Ḥevra Kadisha is different from the others. It is the only permanent, metal plaque—which corresponds to the permanent, established right of the association to collect funds in the synagogue “in the course of Torah reading and the

Misheberakh” (

DIH 1899, p. 16). The other plaques offer associations or specific events and goals, such as “High Holiday expenses” (

Figure 8).

The synagogue regulations of the community of Debrecen from the end of the nineteenth century stated explicitly that the first three people called up to the Torah could offer charity only for the purpose of Ẓedakah, meaning the general charity fund of the community, and then from the fourth onwards also to the Ḥevra Kadisha and the school (ibid, p. 17). Beginning with the fourth person, charity could go to other causes as well, but then the Tzedakah-fund was entitled to half the sum. The structure of the shnoder-sign in the synagogue echoes the specific local regulations. The sign for Ẓedakah is the largest, and it is located centrally, which reflects the privileges of the Ẓedakah-fund. The signs for the Ḥevra Kadisha and the school are the next in size and prominence, again in accordance with the special regulations regarding them. The format and location of the six other charitable causes (high holydays, canteen, poor, seudah shlishit (the third meal on Shabbat), women’s association and cantor) around the Ẓedakah-sign reflect their subordinate status.

The Zionist weekly paper

Zsidó Szemle (Jewish Review) reported in October 1920 that fifty members of the Jewish community of Debrecen asked the community leadership for permission to offer charitable donations during the Torah reading to the Jewish National Fund (KKL:

Keren Kayemet le-Yisrael). Their request was rejected on the grounds that the Jewish National Fund was neither a charitable organization, nor did it fulfill cultural purposes, and “its goal is to strengthen the Zionist movement, which is alien to the sentiments of the Jews in Debrecen.”

23 Zionist historiography connects the appearance of the KKL as one of the possible options for synagogue donations to Theodor Herzl personally (

Berkowitz 1996, p. 172). Herzl’s aim was to replace the traditional forms of support for Jews in the Holy Land and to channel these funds to the KKL. In Hungary, Neológ, Status Quo Ante, and Orthodox communities typically opposed Zionism until the Holocaust—albeit for different ideological reasons—and accordingly, the KKL generally did not appear as a charitable option on shnoder-signs in synagogues. There are, however, some exceptions—possibly from after the Holocaust.

24Nonetheless, the traditional funds to support the Holy Land do appear on many shnoder-signs in orthodox synagogues. It was, in fact, an established custom from the medieval period onwards to collect funds in the Diaspora to support Jewish life in the Holy Land, and there was an ongoing debate about whether the poor in one’s own city had precedence over those in the Holy Land. Interestingly, the term used for funds to be sent to the Holy Land was not uniform. In the western parts of the Hungarian Lands, the term that appears on shnoder-signs is

Aniyei Ereẓ Yisrael (the poor of the Holy Land),

25 whereas in the eastern parts and in Transylvania, it is Rabbi Meir Baal ha-Nes.

26 The term

Aniyei Ereẓ Yisrael is more general, and this is the one that was common in rabbinic literature. Naming funds intended for the Holy Land after Rabbi Meir Baal ha-Nes originates in a Talmudic legend about him and his miracles,

27 and it became especially widespread in the late nineteenth century in Eastern Europe, and predominantly so in Hasidic circles. According to Samuel Kohn, this custom spread in the Hungarian Lands as an influence of Hasidism, and charitable donations for this purpose were connected to the anticipation of miraculous wonders (

Kohn 1899, p. 18). However, whatever name the communities used for these funds, the money was collected and sent to the Holy Land centrally. This is illustrated by the case of the rabbi in Hejőcsaba, Jonathan Alexandersohn, in the 1830s. He wanted to use the money from the R. Meir Baal ha-Nes funds for the education of poor or orphaned children, but the Ḥatam Sofer of Pressburg, who was responsible for collecting and sending the funds to the Holy Land, intervened and strictly forbade him to do so (ibid, p. 18).

There are certain shnoder-signs that are obviously documents of a given historical and political era. For example, on the shnoder-sign in the Miskolc Kazinczy street synagogue (see

Figure 4 above) there are twelve possible beneficiaries on the plaques in the wooden frames, and their names appear in Hebrew and in Hungarian. In the case of an orthodox synagogue in Miskolc, in the North-Eastern part of Hungary, already the use of Hungarian on the

bimah indicates a rather late date, as orthodox communities in this region tended to be cautious about linguistic assimilation. The fact that the KKL appears among the charitable causes suggests a date later than the Holocaust. However, the most obvious indication of an immediate post-Holocaust date is the

Malbish Arumim (“clothing the naked”), one of the common charitable organizations, which is translated into Hungarian as “clothing the deportees.” The fixture itself probably dates from before the war, but the plaques were obviously replaced after the reestablishment of the community in 1945. The wooden shnoder-sign held in the offices of the Budapest Jewish Community’s rabbinate (see

Figure 1) dates from 1949. There are six slots on it, but not all of them have the name of a charitable in them. When it was made, the artisan probably had a traditional charity structure in mind, but after the Communist takeover, the autonomous associations ceased to exist. They were all nationalized, as were educational and social welfare institutions, and thus the place of specific charitable organizations remained empty.

5. The Appearance (and Eventual Disappearance) of Shnoder-Signs

Other than for the few exceptions already mentioned, it is very rare for the shnoder-signs to have an inscription with the date when the sign itself was donated. Therefore, it is hard to know when exactly they were made, and thus it is also hard to establish when shnoder-signs appeared and how they became widespread. There are, however, several factors that suggest the dates of the shnoder-signs. As seen above, in certain instances the date of a shnoder-sign can be established based on the dates when societies mentioned on it were established—and in the cases both of Szeged and of Debrecen, these dates suggest that the shnoder-signs were made in the late nineteenth or the early twentieth century. In some instances, it is the material and the design of the shnoder-signs that help us date them, and especially so if the synagogue interior is of another style. For example, the interior of the synagogue in Lovasberény is baroque (built in the late 1790s, redesigned in the 1820s, destroyed in 1947), and on the

bimah, there is a strikingly different shnoder-sign: An elaborate secessionist iron arch—which was obviously inserted at the beginning of the twentieth century (

Figure 9). There are also historical and sociological factors that suggest that shnoder-signs developed in the late nineteenth and became widespread in the early twentieth century.

In 1916 Bertalan Kohlbach, a rabbi with interest in ethnography, described a shnoder-sign that got into the collection of the Hungarian Jewish Museum just a few years after it was founded in 1909. He added the explanation that the needs of the modern era led to the establishment of many new charitable associations, and “the community provides guidelines to the benefactors” with this fixture on the

bimah (

Kohlbach 1916, pp. 243–44). The dual monarchy—the period between 1868 and World War I in Austro-Hungary—did indeed bring about the appearance of a larger number of organizations and associations in the Jewish, as well as the non-Jewish, world, with a very broad range of functions. The need to publicize and present the various options for donations might have been a reason for the development of such shnoder-signs. Especially since, in this period, Jews in urban environments tended to be less connected to Jewish communal life and to be more secularized, and those who visited the synagogue on rare occasions or for high holidays only might have actually needed the reminders and guidance. On the other hand, as seen in the cases of Szeged and Debrecen, the shnoder-signs were not a way to simply publicize charitable causes, but rather, to legitimize some of them. This need for legitimization also explains why there are shnoder-signs in smaller communities with just two to four charitable causes on them, which definitely is a number that could have been remembered as well.

28Another explanation for the appearance of shnoder-signs is a change in synagogue customs in the nineteenth century. Up until then, the general custom was to auction certain honors in synagogue life, among them the honor of being called to the Torah.

29 According to data collected by Ron S. Kleinman (

Kleinman 2010;

Kleinman 2014), in the majority of Russia and of the territories of Poland, this custom was dropped in the early nineteenth century, possibly in accordance with a prohibition attributed to the Gaon of Vilna.

30 In German territories, the custom was gradually discontinued in the middle of the nineteenth century, first, in communities known for introducing liturgical reforms of all kinds, but eventually, in orthodox communities as well (

Kessler 2007, p. 143). In Hungary, when the great synagogue in Pest on Dohány street was inaugurated in 1859, the honor of doing duties around the Torah was still auctioned.

31 As seen in community and Hevra Kadisha regulations, the custom was discontinued in Szeged in 1870 (

Löw and Kulinyi 1885, p. 71;

Löw and Klein 1887, p. 283), and eventually it disappeared in Neológ communities all around the country by the turn of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The arguments in favor of discontinuing the custom of auctioning included maintaining the dignity of synagogue services, avoiding awkward debates, preventing undeserving people from buying the honors, and circumventing situations that might cause outrage in external observers. The donations that used to be collected from the auction came to be replaced by donations offered during the

Misheberakh prayer, and thus shnoder-signs started appearing in synagogues. Orthodox communities often preserved a double system, where certain honors around the Torah were sold,

32 but there were also spontaneous donations during the

Misheberakh prayer—and thus eventually, shnoder-signs appeared there as well.

In contrast, in Hasidic environments, if there are fixtures on the

bimah at all, they typically contain the blessings only and do not name any possible charitable causes.

33 In fact, the custom of shnoder-donations did not become common in Hasidic communities. Thus, yet another plausible explanation for the appearance of shnoder-signs is that they demonstrate a certain type of order and legitimacy as opposed to the spontaneity and perceived disorder of Hasidic communities—which fits into the atmosphere of the denominational tensions of the period.

After the Communist takeover in 1948/1949, when the various independent associations and organizations ceased to exist, the shnoder-boards lost their function in synagogues of all denominations, and the knowledge of their original use faded fast from communal memory. Not having a name, and not having a function, many of the shnoder-signs remained unnoticed by worshippers. In some synagogues, only the empty frames survived, the original charitable causes disappeared or were removed, never to be replaced.

34 In others—for example in Eperjes (Prešov, Slovakia)—the original frames survived, but received a new function: The names of the 12 months were inserted into the 11 frames (

Figure 10), and yet others disappeared during renovations—lacking a name, a function, or any communal consciousness.

6. Keeping Track of Promises Made on Shabbat and on Holidays

Donations offered on Shabbat or holidays cannot be paid on site, nor can the promise be written down, since according to the regulations prohibiting certain activities on Shabbat and holidays, it is forbidden both to touch money and to write. Therefore, in order to keep a record of the promises, and to make sure that these promises can be claimed during the week afterwards, a solution had to be found that did not violate Shabbat regulations. This solution had to record at least two kinds of information: The name of the benefactor and the amount of the donation. In the case of an auction, or in the case when a synagogue belongs to a specific society, these two kinds of information are sufficient. However, in the case of communities with more than one possible charitable cause, also the purpose of the donation has to be recorded. In the case of the shnoder-books described below, it is not always obvious which type of donations they were used to record.

There are a number of techniques known to have been used by Jewish communities around the world to solve the problem of recording charitable donations on Shabbat, and the variety itself is of great interest. Neither scholarly literature on this subject nor a suitable amount of data is available for conclusions to be drawn with regard to how widespread each practice was in terms of geography and time.

35 It was presumably the exact needs and inventive spirit particular to any given community that determined which solution was used. Memorizing all information related to charitable donations is also an option, and there have always been communities that trust the memory and reliability of the benefactors. Other communities decided to use a form of exogram,

36 and the reason for this is most probably not just the limitation of human memory. As also suggested in the case of shnoder-boards, that presenting the possible charitable donations in the physical space of the synagogue might have been a result of the need for order, for a transparent system, and modern esthetic needs.

One widespread way in which donations could be recorded without violating the laws of Shabbat was the use of a container which has a number of envelopes or pockets, with the names of the members of the community, the beneficiaries, or the given occasion written on them. There had to be many small slips of paper in this container, with the important variables of the donation marked on them, with those missing from the envelopes or pockets each placed in separate little packs. Then, during the Torah reading, the variables of the donation are inserted in the appropriate envelope, pocket, or box. The simplest form of this technique is when the little slips of paper are placed between the pages of a book, in which case, each benefactor has a separate page. All shnoder-books known from the territory of historical Hungary from before the Holocaust used one form or another of the paper slip technique: Pockets, drawers, cuts, or pages. Due to the ephemeral quality of the material used for these items, the intensive use they are put to, and their minimal spiritual significance, such objects have rarely survived. Two objects are known to have survived from the nineteenth century (from Pápa and from Eperjes (Prešov, Slovakia)), two from the interwar years (from Debrecen and Balassagyarmat), and one from the post-Holocaust period (Budapest, Kazinczy street). There are further objects known from personal memoirs, community regulations—but the objects themselves have perished.

6.1. Pápa

One of the most exceptional Jewish items in the collection of the Museum of Ethnography in Budapest is a leather-bound book from Pápa, acquired by the museum in 1913:

The Offertory Book of the Bikur Ḥolim Society of the Holy Community of Pápa, may the Almighty preserve it, from the year 1829.

37 The

Bikur Ḥolim was one of the common societies in traditional Jewish communities to support and visit the sick. According to its own Yiddish title, the book from Pápa is an

aynlegbukh (cf. German

Einlegbuch), which is descriptive of the method applied: ‘an insert-book.’ The book contains 14 leaves, and there are five rows of four pockets glued on both sides of each leaf, that is, there are 20 pockets on each page, and 500 pockets altogether on 25 pages. On the pockets, there are names of men: The names of potential benefactors to the

Bikur Ḥolim Society, written in Hebrew quadrate characters. The names appear in alphabetical order, with some pockets left empty after each letter of the alphabet, presumably counting on potential new members in the future. The pages of the book are turned in accordance with the direction of Hebrew script, from right to left. Four hundred twenty-three of the 500 pockets have names on them. When in use, little slips of paper were inserted in the pockets, containing promised donations by the individual to the Society (

Figure 11).

This book was recycled from another book. In its second use, after every five, six leaves, four to six were cut out. The remaining leaves in the book were then glued together, thus creating the 14 leaves. The pockets themselves were made from the cut-out pages. Folded in, the paper pockets measure 60 × 55 mm (2.35 × 2.1 inches). Their bottom and side edges were folded in and used to glue the pockets to the pages. The restoration work revealed that, in some cases, the pockets were readdressed, with the new name written on a piece of paper glued ontop of the original. In other cases, names were simply crossed out and overwritten to update them, and names also were added later to empty pockets, their later addition can be presumed from the difference in letter types and the different ink or graphite used. On seven pockets, in addition to the names, there are also remarks regarding certain amounts these individuals still owed, written in German with Hebrew cursive characters: “40 remaining”, “pending: 70”, “borrowed 40, which now A. Löwenstein has”.

In the course of restoration, little slips of paper were found in five of the pockets, one or two in each. These have inscriptions in German Hebrew cursive characters, mentioning various amounts of wine: 2 Halbe Wein (ca. 1.68 L, that is 35 ounces of wine), 1 Seitel Wein (ca. 0.35 L, that is 12 ounces of wine).These paper slips probably remained in the pockets as remnants of previous offers of donations, so offers other than money could also be made to the Society.

6.2. Eperjes/Prešov

The other shnoder-book from the nineteenth century was also preserved in a museum: The Jewish Museum of Prešov, founded in 1928. It was considered to be one of the more significant objects of the collection from early on (Inv. no. 1474-III-759).When the museum issued a collection of 12 postcards in 1929, this was one of the items—along with many

mezuzah cases, and it was on the museum’s information board (

Švantnerová 2019, pp. 11–39, figs. 9 and 11). Its use was similar to that of the shnoder-book of Pápa, except that in this one, the individual members of the community each had a little compartment glued to a thin wooden board, with lids that could be opened or closed. There are five rows of 12 compartments—altogether 60 compartments. On their lids, there are names of men. Some of the names were glued over or corrected, as the membership of the community changed. The names were written with a quill and black ink, with Latin script characters, in the Hungarian order of names: First the family name, and then the first name, often abbreviated. Due to the later corrections, the alphabetical order is not consistent (

Figure 12).

This shnoder-book was in use since 1846, and the original names in it include the founders of the Jewish community in Eperjes as as well as the founders of the first communal institutions: Leó Holländer, Leó Schäfer, Móric Schiff, Ignác Klein, József Spiegel, Markus Barkan (

Lányi and Popperné 1933, p. 160).

38 The number of Jewish inhabitants in Eperjes grew rapidly in the following decades. While in 1851, there were 170 Jews there, in 1880, there were already 1221 (

Jelinek 2007, p. 485). This object could not accommodate such rapid growth in the number of male members—and potential benefactors—in the community. Due to the small number of compartments, in the 1860s, the community probably had to look for other solutions to register charitable donations on Shabbat.

6.3. Debrecen

There is a thin piece of cardboard used for a similar purpose exhibited in the yeshiva and rabbi’s house in Mád, renovated and converted into a museum recently (in 2016) by the Unified Hungarian Jewish Community (EMIH/Chabad of Hungary). The item was originally used in the Orthodox synagogue of Debrecen in the interwar years and came to Mád from the private collection of Zsolt Heller, president of the Foundation for the Jewish Temple and Cemetery of Debrecen. There are two pieces of cardboard in the exhibit, but judging by the Roman numerals on their upper right corner, there probably were more, and the small holes found on the left edge of the boards suggest that they were bound together like a book. There are several small pockets on each board, with the order that people are called up to the Torah written on them (Kohen, Levi, etc.). The name of the benefactor and the amount of the donation were inserted in these pockets on small slips of paper. Today, the item is exhibited as an alijatábla (board for honors of the Torah), and apparently, back in its day, it was used under the name snódertálca (snóder-tray). However, it is not clear whether the object was used to record the results of the sale or auctioning of the honors or spontaneous donations.

6.4. Balassagyarmat

Balassagyarmat used to be a community with approximately 2000 members. In one of the smaller prayer houses of the community, today known as the “small synagogue,”, there is a shnoder-book from the interwar years as an exhibition item. Similar to the shnoder-book from Debrecen, it is between a book and a tray. Instead of the names of the potential beneficiaries, it has their seat number on each compartment—which then did not need to be corrected and updated to keep up with the fluctuating community membership. In a smaller synagogue, it was easy to remember and follow where people sat. Above each seat number, there was a small cut, and the little triangular slips of paper with the sums could be inserted in these slots. These slips of paper were held in pockets on the opposite page, arranged according to the sum they represented. Each pocket said what the amount was on the slips of paper held in that pocket. This book can be dated according to the currency on the slips of paper: It uses

pengő and

fillér—the currency used in Hungary between 1928 and the Holocaust.

39 7. Sources Regarding the Use of Shnoder-Books

Based on memoirs, accounts, and personal interviews, it is obvious that shnoder-books were in use in other communities as well, but the objects themselves did not survive, and the descriptions are often not pedantically detailed. In the regulations of the

Hevra Kadisha in Szeged written in 1800, there is an obvious reference to the use of a book similar to the shnoder-book of Pápa: “Offers of donation in the synagogue are to be inserted (

einlegen) in the book reserved for this purpose” (

Löw and Klein 1887, p. 27)—the object itself, however, is not known.

From Dunaszerdahely (Dunajská Streda, Slovakia), the memoir of Ferenc Kornfeld also describes the use of a shnoder-book: “[…] those who were called up to the Torah in those days would always give a donation, but these donations could not be written in the records on Shabbat, so there was this book with little envelopes glued into it, each bearing a name. There were small slips of paper with possible amounts written on them, and these paper slips would be inserted into the envelopes until the person redeemed them. We found this book, and I could establish that there were two hundred and thirty-seven men attending the synagogue immediately after1945” (

Bacskai 2004, p. 177). This technique is essentially identical to that used by the offertory book of Pápa: Every potential donor, meaning all adult male members of the community, had a pocket in the book, the names appearing in the order of the Hebrew alphabet. In the course of reading the Torah, when the donation was announced, a paper slip with the previously specified amount of the donation was inserted in the relevant pocket. For this specific type of donation, he even uses the Hungarian verb

snóderol.

In the orthodox community of Jánoshalma, according to the memories of R. Herman Schmelzer, before the Holocaust, they used to have a simple book as a shnoder-book. There was a name on each page, and there were little slips of paper written in advance, and those papers were placed between the pages on Shabbat and on holidays. The local teacher was responsible for keeping track, and therefore, he sat close to the

bimah to make sure he heard all donations accurately.

40 In Győr they used a similar system in the 1950s, everyone had a separate page, and the pre-written little slips were placed between the pages.

41One of the basic accessories of all shnoder-books is a box or several envelopes where the little slips of paper were kept in order. The obvious reason for such boxes or envelopes is practical: The many slips of paper with various information on them have to be organized in order to make the use of the shnoder-book fast and smooth. Nevertheless, there are also halakhic reasons: One of the categories of work prohibited on Shabbat is

borer (sorting), and sorting the slips, or taking the relevant one out of a mixture might fall into this category, also, moving the slips of paper with amounts of money on them might fall into the category of

mukẓeh (here: Items that are not allowed to be moved on Shabbat) (

Roth 1981, pp. 166–67). Therefore, accompanying the shnoder-books, there often used to be little boxes with separate compartments where the slips were sorted by category or value. For example, there are two such boxes that can be locked in the collection of the Jewish Museum of Prešov.

42There are two further such boxes in the orthodox community in Budapest on Kazinczy street: In the winter synagogue and in the

Shas Ḥevra prayer room. In the winter synagogue, after World War II they used a shnoder-book with an alphabetical register, with nine names on each page and two small slots below each name. To accompany this, there are small triangular slips of paper in a separate wooden box. These papers show possible amounts, occasions, and beneficiaries of the donations. These small triangular slips of paper were slipped in the slots under the names to record the donations. The book and the box are still in the collection of the community, though no longer in use. The box of the

Shas Ḥevra prayer room was used on its own, without any book: The box had little slips of paper with names, sums, and the order of donations (e.g., third, sixth), and the charity donations were registered by grouping these slips of paper together (

Raj and Szelényi 2002, p. 33) (

Figure 13). The slips of paper with the order of people called up to the Torah—just as in the case of the shnoder-book of Debrecen—indicate that this item was used for auctioning or selling the honors, and not for spontaneous donations.

It is customary to give donations in symbolic amounts—for example, some multiple of eighteen (eighteen being the numerical value of the Hebrew word

ḥay, which means ‘living’, ‘the One that is eternally live’). Often, the sums do not appear in the currency of the country at the time—and thus, it could be avoided to talk about actual sums of money on Shabbat. In the Habsburg Monarchy, the common offer of “Chaj-Zall” (18 Kreutzer) does not represent the actual currency, it meant different amounts in different communities and periods (

Roth 1981, p. 166). In the archives of the Jewish Community of Pécs, there is a collection of small slips of paper with sums on them in Hebrew, and over one-third of them contain the term “Chaj-Zall.” There is no shnoder-book to accompany these slips of paper, and so it is impossible to tell what community they come from—and there are several well-established communities in the region, such as Bonyhád and Mohács, whose archival material is now held in Pécs (

Figure 14).

43 As recalled by an interviewee, in the interwar years in the community in Sátoraljaújhely, the expressions ‘tózend micve, cvajtózend micve, etc.’ were used, rather than indicate the currency.

44 Techniques from after the Holocaust

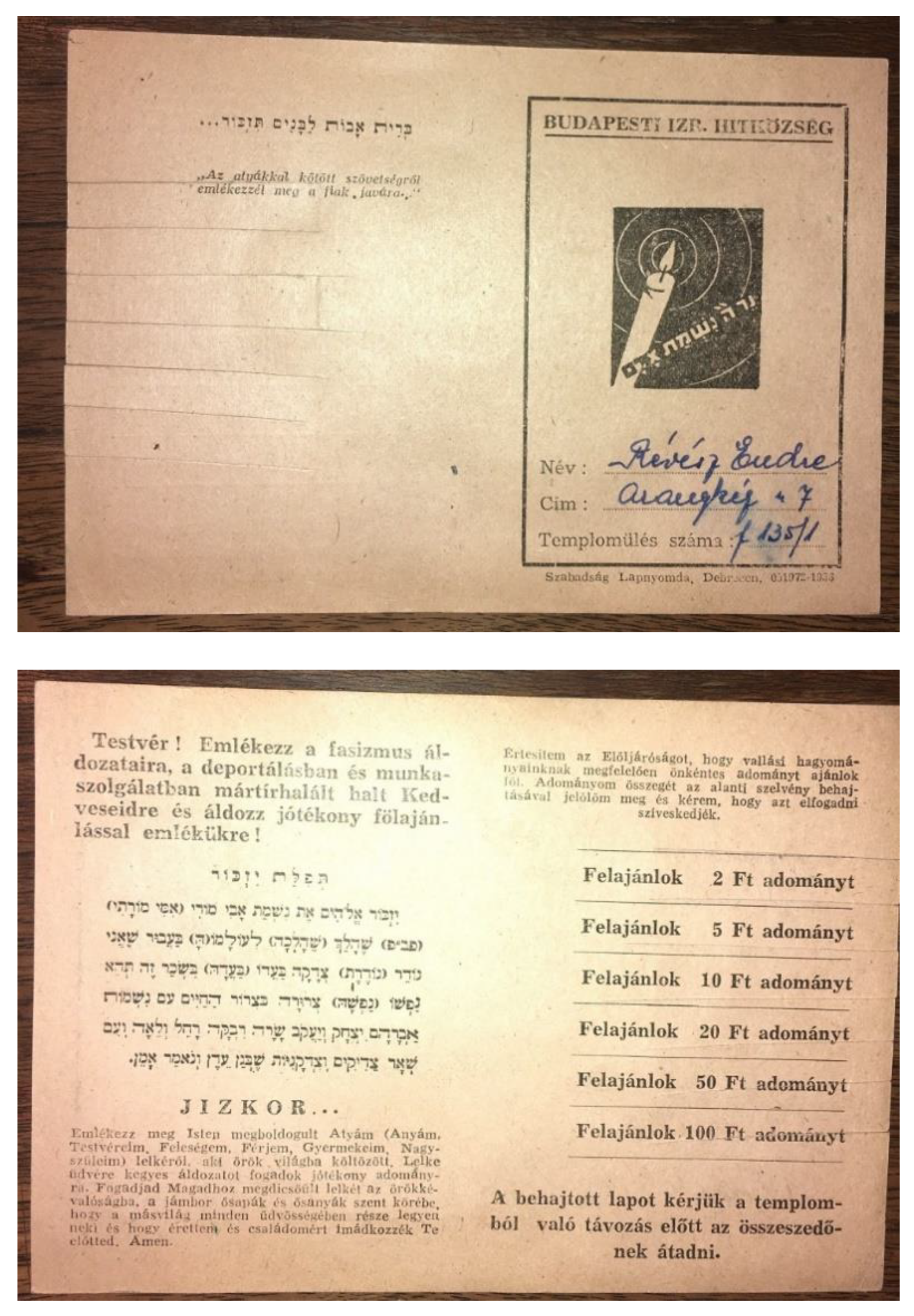

As already seen, the shnoder-signs lost their function soon after the Holocaust. In Hungary, the size of the surviving communities, as well as the change in social and political structures, especially after the Communist takeover in 1948–1949, led to the change of the customs, the dynamics, and purposes of charitable donations. As part of this process, the exogram techniques changed as well.

45 One of the methods that became common in Hungarian communities in the mid-twentieth century was to print uniform slips of paper for shnoder-donations, with various sums on it, with cuts in it between the sums. The benefactor then had to fold in the sum he wanted to donate (

Figure 15).

46 These were mass-printed slips of paper, single-use only. In Debrecen, they were mailed to the congregants before

mazkir (the memorial services on certain holidays), probably also to urge attendance. They then had to bring the slips of paper with them to the synagogue.

47 We have data on the use of similar slips from Budapest and Jánoshalma as well.

48 Another parallel custom was for the congregants to write their names and the donation details onto slips of paper, and hand it over to those in charge during the Torah service. This custom had its halakhic problems: The slips of paper would have to be written by the congregants before the Shabbat or the holiday, and there were difficulties also regarding the carrying of these slips of paper to the synagogue—accordingly, this custom was more typical in communities where religious observance was more lax. In any case, these slips of paper were even more ephemeral than any of the previous solutions to recording charitable donations, and they hardly had any chance to survive.

The shnoder-signs, as well as the shnoder-books, developed as a result of the needs arising from ritual practice and social circumstances. Shnoder-signs developed in the very specific geographical region of historical Hungary, and in the very specific time period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Its emergence reflects the changes that some of the Jewish communities of Hungary underwent in this period, i.e., urbanization, secularization, and the divisions, according to various religious movements. As soon as the local practice and the social and political atmosphere changed after the World War II, there was no use for them anymore, they fell into oblivion. The use of shnoder-books spans a significantly larger time-period, as well as geographic area, since they were known in most of Western Ashkenaz, but they disappeared due to the ephemeral nature of their use, and eventually their use, too, faded due to changing community structures and modernity. Neither one of these objects is part of mainstream discussions of synagogue customs, interiors, fixtures, and accessories.

Examining these two sets of objects highlights the usefulness of the approach of focusing on the use of space and physical objects during the ritual events in a synagogue. Taking a closer look at the schnoder signs of the synagogue in Debrecen and Szeged has also shed light on how minutely the physical appearance and material properties of these objects reflect the regulations in place at the given time and location. Researching the written sources of particular communities and regions and connecting them with their surviving objects can yield whole new considerations to the research of synagogues.