The Hanging Garlands of Pompeii: Mimetic Acts of Ancient Lived Religion

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Lived Religion and Painted Religious Scenes in Pompeii

3. Flower Garlands in Roman Religion

4. Physical Evidence for Hanging Garlands on Roman Walls

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CIL | Corpus Inscriptionum Latinarum. |

| LIMC | Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae. 1981–2009. Zurich: Artemis. |

| PPM | Carratelli, Giovanni Pugliese, Ida Baldassarre. 1990–2003. Pompei: Pitture e mosaici. Rome: Istituto della encyclopedia italiana. |

| ThesCRA | Balty, Jean-Charles, 2004-present. Thesaurus Cultus et Rituum Antiquorum. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum Press. |

References

- Albrecht, Janico, Christopher Degelmann, Valentino Gasparini, Richard Gordon, Maik Patzelt, Georgia Petridou, Rubina Raja, Anna-Katharina Rieger, Jörg Rüpke, Benjamin Sippel, and et al. 2018. Religion in the Making: The Lived Ancient Religion Approach. Religion 48.3: 568–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnabei, Lorenza. 2007. I culti di Pompei. Raccolta critica della documentazione. In Contributi de Archeologia Vesuviana III. Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider, pp. 7–88. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, Maddalena. 2008. Sacraria: Ambienti e Piccolo Edifice per il Culto Domestico in Area Vesuviana. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, vol. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, Maddalena. 2017. Sacra Privata Nell’italia Centrale: Archeologia, Fonti Letterarie e Documenti Epigrafici. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, vol. 40. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, Maddalena, and Francesca Ghedini, eds. 2011. Religionem Significare: Aspetti Storico-Religiosi, Sturtturali, Iconografici e Materiali dei Sacra Privata. Rome: Edizioni Quasar, vol. 19. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary, John North, and Simon Price. 1998. Religions of Rome, Volume 1: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Belayche, Nicole. 2007. Religious Actors in Daily Life. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jörg Rüpke. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 275–91. [Google Scholar]

- Bowerman, Helen Cox. 1913. Roman Sacrificial Altars: An Archaeological Study of Monuments in Rome. Ph.D. dissertation, Bryn Mawr College, Pennsylvania, PA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Bowes, Kimberly. 2015. At Home. In A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. Edited by Rubina Raja and Jörg Rüpke. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 209–19. [Google Scholar]

- Boyce, George. 1937. Corpus of the Lararia of Pompeii. Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Rome: American Academy in Rome, vol. 14. [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessio, Maria Teresa. 2009. I Culti di Pompei: Divinità, Luoghi e Frequentatori (VI secolo a.C.-79 d.C.). Rome: Libreria dello Stato. [Google Scholar]

- Dungworth, David. 1998. Mystifying Roman Nails: Clavus Annalis, Defixiones, and Minkisi. In TRAC 97: Proceedings of the Seventh Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Nottingham 1997. Edited by Colin Forcey, John Hawthorne and Robert Witcher. Oxford: Oxbow Books, pp. 148–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, Steven. 2018. The Roman Retail Revolution: The Socio-Economic World of the Taberna. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 1995. Art and the Roman Viewer: The Transformation of Art from the Pagan World to Christianity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elsner, Jaś. 2007. Roman Eyes: Visuality & Subjectivity in Art & Text. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Flower, Harriet. 2017. The Dancing Lares and the Serpent in the Garden: Religion at the Roman Street Corner. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Foss, Pedar. 1997. Watchful Lares: Roman Household Organization and the Rituals of Cooking and Eating. In Domestic Space in the Roman World: Pompeii and Beyond. Edited by Ray Laurence and Andrew Wallace-Hadrill. Portsmouth: British Academy, pp. 197–218. [Google Scholar]

- Fröhlich, Thomas. 1991. Lararien- und Fassadenbilder in den Vesuvstädten: Untersuchungen zur ‘volkstümlichen’ Pompejanischen Malerei. Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, Valentino, Maik Patzelt, Rubina Raja, Anna-Katharina Rieger, Jörg Rüpke, and Emiliano Urciuoli, eds. 2020. Lived Religion in the Ancient Mediterranean World: Approaching Religious Transformations from Archaeology, History, and Classics. Berlin: De Gruyter. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacobello, Federica. 2008. Larari Pompeiani: Iconografia e Culto dei Lari in Ambito Domestico. Milan: Edizioni Universitarie di Lettere Economia Diretto. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume-Coirier, Germaine. 1995. Images du coronarius dans la littérature et l’art de Rome. Mélanges de l’École Française de Rome, Antiquité 107: 1093–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guillaume-Coirier, Germaine. 1999. L’ars coronaria dans la Rome antique. Revue Archéologique 2: 331–70. [Google Scholar]

- Guillaume-Coirier, Germaine. 2002. Techniques coronaires romaines: Plantes “liées” et plantes “enfilées”. Revue Archéologique 1: 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartnett, Jeremy. 2017. The Roman Street: Urban Life and Society in Pompeii, Herculaneum, and Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Honroth, Margret. 1971. Stadtrömische Girlanden: Ein Versuch zur Entwicklungsgeschichte römischer Ornamentik. Vienna: Im Selbstverlag. [Google Scholar]

- Jansen, Gemma C. M. 2011. Cultural Attitudes. In Roman Toilets: Their Archaeology and Cultural History. Edited by Gemma C.M. Jansen, Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Eric M. Moormann. Babesch Supplement 19. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 165–76. [Google Scholar]

- Jashemski, Wilhelmina. 2018. Produce Gardens. In Gardens of the Roman Empire. Edited by Wilhelmina F. Jashemski, Kathyrn L. Gleason, Kim J. Hartswick and Amina-Aïcha Malek. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 121–51. [Google Scholar]

- Kastenmeier, Pia. 2007. I Luoghi del Lavoro Domestic Nella Casa Pompeiana. Rome: “L’Erma” di Bretschneider. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann-Heinimann, Annemarie. 2007. Religion in the House. In A Companion to Roman Religion. Edited by Jörg Rüpke. Malden: Blackwell, pp. 188–201. [Google Scholar]

- Koloski-Ostrow, Ann Olga. 2015. The Archaeology of Sanitation in Roman Italy: Toilets, Sewers, and Water Systems. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Laforge, Marie-Odile. 2009. La Religion Privée à Pompéi. Naples: Centre Jean Bérard. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner, Martin, and Steven Kossak. 1991. The Lotus Transcendent: Indian and Southeast Asian Art from the Samuel Eilenberg Collection. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. [Google Scholar]

- Ling, Roger, and Lesley Ling. 2005. The Insula of the Menander at Pompeii: Volume II—The Decorations. Oxford: Clarendon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lott, J. Bert. 2010. The Neighborhoods of Augustan Rome. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- MacRae, Duncan E. 2019. Mercury and Materialsm: Images of Mercury and the Tabernae of Pompeii. In Tracking Hermes, Pursuing Mercury. Edited by John F. Miller and Jenny Strauss Clay. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, William H. 1985. Catalogue of the Romano-British Iron Tools, Fittings, and Weapons in the British Museum. London: British Museum Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Morales, Helen. 1996. The Torturer’s Apprentice: Parrhasius and the Limits of Art. In Art and Text in Roman Culture. Edited by Jaś Elsner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 182–209. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, David. 1978. Roman Domestic Religion: The Evidence of the Household Shrines. Aufstieg und Niedergang der Römischen Welt 16: 1557–91. [Google Scholar]

- Raja, Rubina, and Jörg Rüpke, eds. 2015. Archaeology of Religion, Material Religion, and the Ancient World. In A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, Dylan Kelby. 2018. Water Culture in Roman Society. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2011. Lived Ancient Religion: Questioning “Cults” and “Polis Religion”. Mythos 5: 191–203. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2015. Individual Choices and Individuality in the Archaeology of Ancient Religion. In A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. Edited by Rubina Raja and Jörg Rüpke. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 437–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg. 2018. Pantheon: A New History of Roman Religion. Translated by David M. B. Richardson. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rüpke, Jörg, and Christopher Degelmann. 2015. Narratives as a Lens into Lived Ancient Religion, Individual Agency and Collective Identity. Religion in the Roman Empire 1: 289–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swetnam-Burland, M. 2018. Material Evidence and the Isiac Cults: Art and Experience in the Sanctuary. In Individuals and Materials in the Greco-Roman Cults of Isis: Agents, Images, and Practices. Edited by Valentino Gasparini and Richard Veymiers. Leiden: Brill, Religions in the Graeco-Roman World, vol. 187, pp. 584–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thüry, Günther E. 2011. Das römische Latrinenwesen im Spiegel der litterarischen Zeugnisse. In Roman Toilets: Their Archaeology and Cultural History. Edited by Gemma C.M. Jansen, Ann Olga Koloski-Ostrow and Eric M. Moormann. Babesch Supplement 19. Leuven: Peeters, pp. 43–47. [Google Scholar]

- Turcan, Robert. 1971. Les guirlandes dans l’antiquité classique. Jahrbuch für Antike und Christentum 14: 92–139. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andriga, William. 2000. Autels de Carrefour, organization vicinale et rapports de voisinage à Pompéi. Rivista di Studi Pompeiani 11: 47–86. [Google Scholar]

- Van Andriga, William. 2009. Quotidien des Dieux et des Hommes: La vie Religieuse Dans les Cites du Vésuve à L’époque Romaine. Rome: École française de Rome. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Lara. 2015a. Perpetuated Action. In A Companion to the Archaeology of Religion in the Ancient World. Edited by Rubina Raja and Jörg Rüpke. Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, pp. 60–70. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Lara. 2015b. Religious Practice at Deir el-Medina. Leuven: Peeters. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | On the mimetic votive, see: (Elsner 2007, pp. 42–45), along with the discussion below. |

| 2 | There are also examples of similar pictorial acts of offering floral garlands in Buddhist art. For example, on a volute of a winged deity from Pakistan from the early Kushan period (first century CE), the deity holds a garland; however, it is believed that the volute itself would have allowed individuals to hang physical garlands on it, too. In addition, at the Great Stupa at Sanchi, a relief shows human and divine beings adorning the structure with garlands, in addition to having hooks to allow for the addition of physical garlands by pilgrims visiting the stupa. For more, see: (Lerner and Kossak 1991, p. 72). |

| 3 | For overviews of the approach of ancient lived religion, see: (Rüpke 2011; Raja and Rüpke 2015; Rüpke 2015; Rüpke and Degelmann 2015; Albrecht et al. 2018; Gasparini et al. 2020). |

| 4 | For example, see: (Laforge 2009; Van Andriga 2009; Bassani 2008; Bassani and Ghedini 2011; Bowes 2015). See also: (Barnabei 2007; D’Alessio 2009). We will not be concerned here with examples of public temples. |

| 5 | Here, we discard painted surfaces that depict mythological scenes as evidence of religious activities in domestic spaces in particular (e.g., Kaufmann-Heinimann 2007, pp. 189–91). |

| 6 | Sometimes these artifacts are not found in situ, which can prove to be problematic for interpretations of how they were used in their original contexts (Bowes 2015). |

| 7 | For more on the associations between the kitchen and religious activities of slaves there, see: (Fröhlich 1991; Foss 1997; Giacobello 2008, pp. 89–126; Bowes 2015, p. 213). |

| 8 | There has been a great deal written about the multi-faceted cult of the lares in Roman religion. The most recent and comprehensive treatment is Flower 2017. There is still discussion in modern scholarship on the differences between the lares and the penates, the former of which were tied to the heath of the home and the latter of which were deities tied by blood to the family. For the purposes of this article, the designation lares will be used. For more on this debate, see: (Fröhlich 1991, pp. 37–48; Laforge 2009, pp. 84–86; Flower 2017, pp. 46–52; Rüpke 2018, pp. 253–55). |

| 9 | The literature on lararia is vast: (Boyce 1937; Orr 1978; Fröhlich 1991; Bassani 2008; Giacobello 2008; Laforge 2009, pp. 47–77; Van Andriga 2009, pp. 217–69; Bassani 2017; Flower 2017). For discussions on the term lararium, see: (Bassani 2008, pp. 61–62; Giacobello 2008, pp. 54–58; Laforge 2009, pp. 19–47). |

| 10 | Pliny, Naturalis historia 21.1.2. For discussions of the Latin terms, see: (Guillaume-Coirier 1995, 1999). See also the later third-century treatise by Tertullian (De corona militis). |

| 11 | Augustus, Res gestae 34. Pliny also describes some of the contexts for wearing crowns (Naturalis historia 21.2). See also: (Guillaume-Coirier 1999, p. 332). For more on the Roman uses of garlands, in addition to Greek and Etruscan, see: (Honroth 1971; Turcan 1971, pp. 108–33; ThesCRA 2.451–6). |

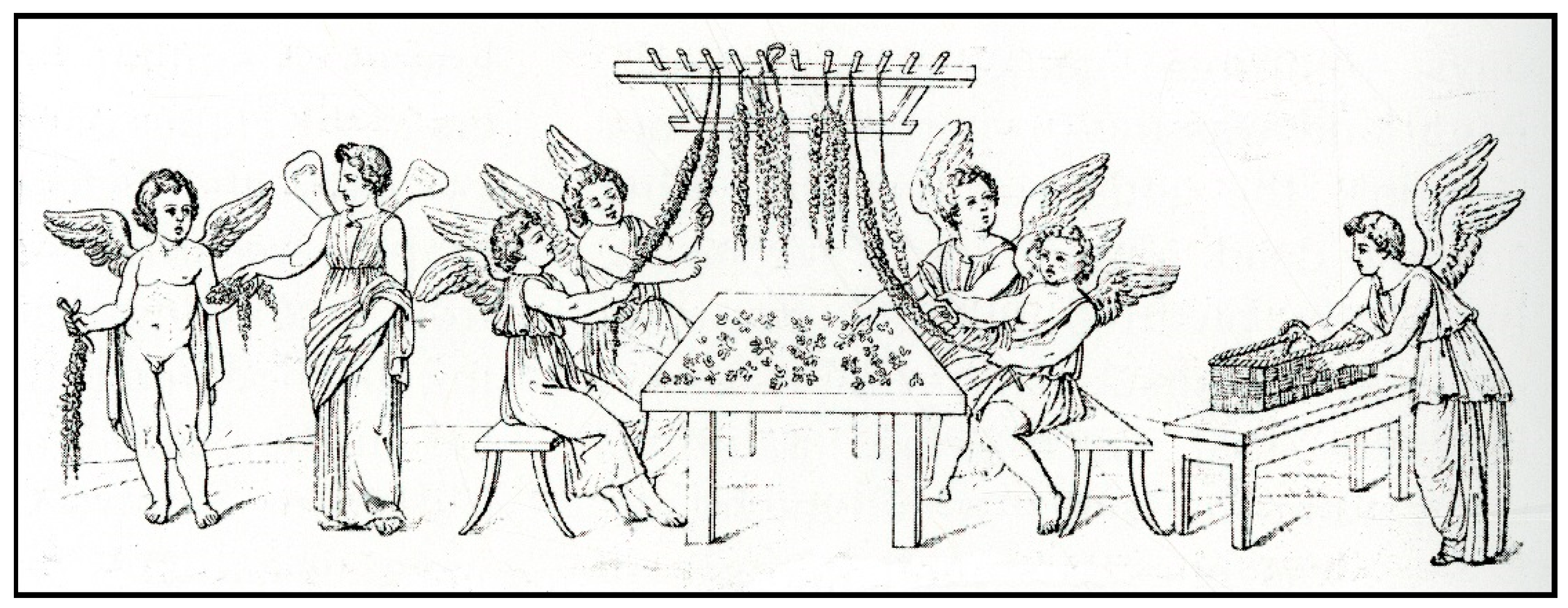

| 12 | For more on the iconographic evidence for the construction of these garlands, see: (Guillaume-Coirier 1995, pp. 1108–51). |

| 13 | Plautus, Aulularia 23–25, trans. H.I. Flower. Ea mihi cottidie aut ture aut vino aut aliqui semper supplicat, dat mihi coronas. For a full discussion of this passage, see: (Flower 2017, pp. 31–35). |

| 14 | Cato, de Agricultura 143, trans. H.I. Flower. Kalendis, idibus, nonis, festus dies cum erit, coronam in focum indat, per eosdemque dies lari familiari pro copia supplicet. For a full discussion of this passage, see: (Flower 2017, pp. 40–45). |

| 15 | (Lott 2010, pp. 81–127; Flower 2017, pp. 255–347). Flower asserts that these shrines were not in fact dedicated to the lares Augusti; for more on this argument, see: (Flower 2017, pp. 299–312). |

| 16 | Suetonius, Augustus 31.4. See also: (Lott 2010, pp. 115–17; Flower 2017, pp. 273–74, 339). Ovid also reports that a temple associated with the lares in Rome was often venerated with garlands (Fasti 6.792). |

| 17 | For more on whether or not urban centers outside of Rome renamed their neighborhood lares to align with Rome, see: (Van Andriga 2000, pp. 78–80; Flower 2017, p. 345). |

| 18 | Theod. Cod. 16.10.12 pr., trans. H.I. Flower. For a discussion of this passage, see: (Flower 2017, pp. 348–51). |

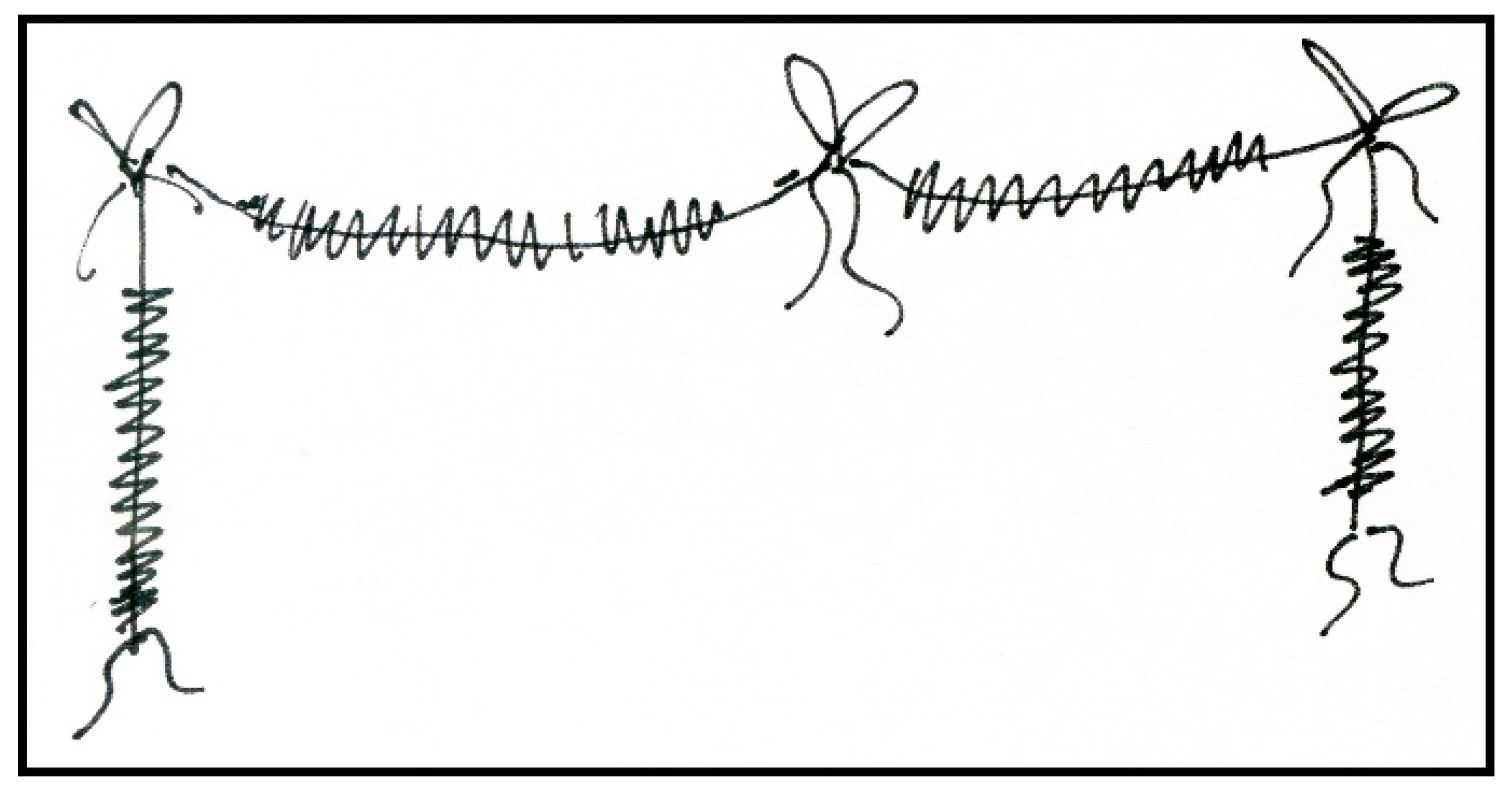

| 19 | While there are countless painted garlands on the walls of Pompeii, it is beyond the scope of the present paper to address evidence for physical hanging garlands outside of religious images. |

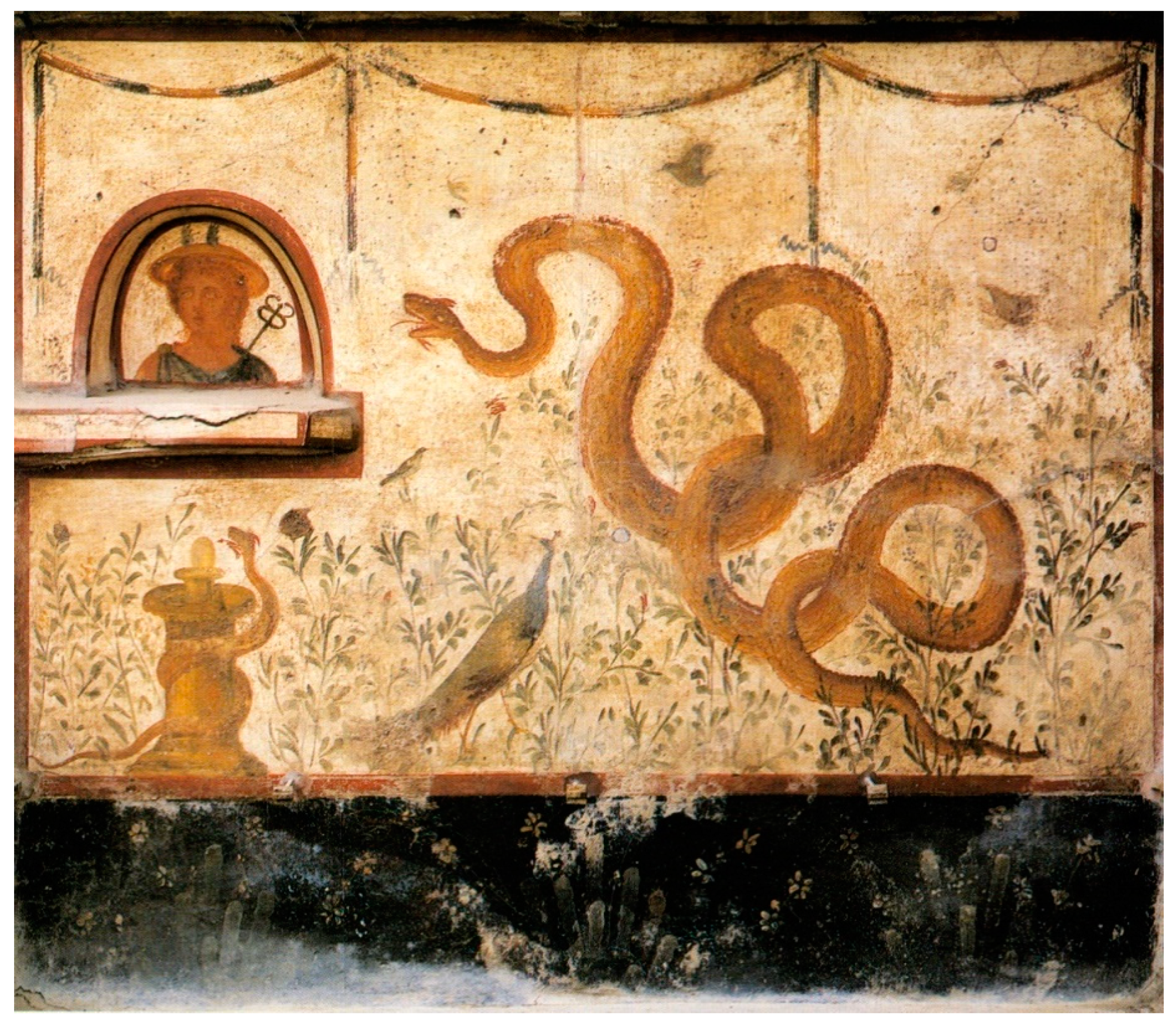

| 20 | Not all painted garlands were rendered schematically; there are examples of detailed garlands on the painted surfaces of Pompeii. For example, the famous image of the god Dionysus in front of Mount Vesuvius from the Casa del Centenario (9.8.3-6) includes a finely rendered garland, with discernable roses and green leaves. The panel was part of a larger lararium shrine, with lares and a niche. See: (Fröhlich 1991, cat. no. L107; Giacobello 2008, cat. no. 108). |

| 21 | On Roman nail types, see: (Manning 1985, pp.134–37; Dungworth 1998). |

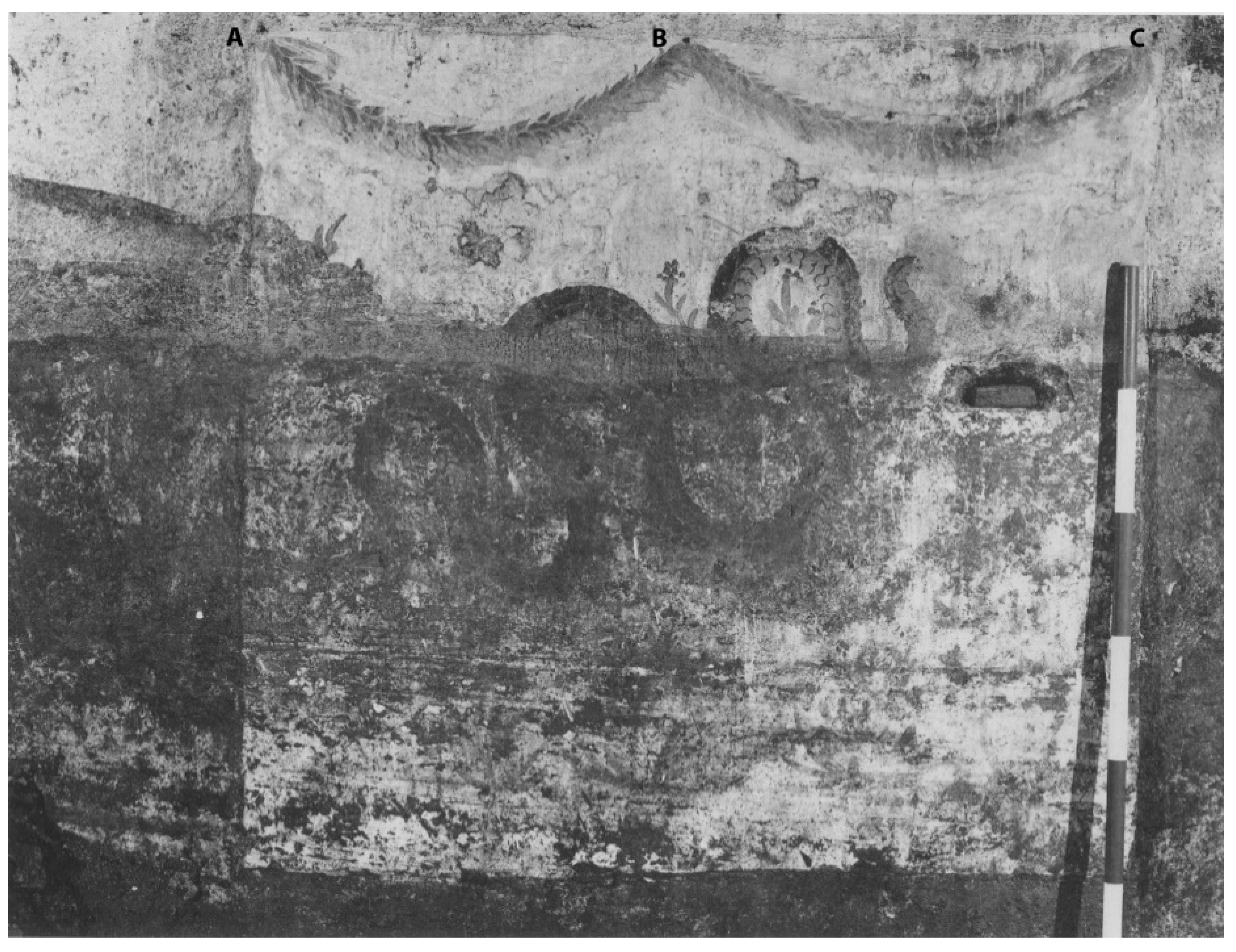

| 22 | For example, Boyce, in his corpus of lararia in Pompeii only mentions three examples (Boyce 1937, cat nos. 213, 349, 459). Flower does have passing mentions of the evidence of nails as indicators of religious practice around these painted spaces (e.g., Flower 2017, p. 75). |

| 23 | For more on depictions of the lares in commercial spaces, see: (Ellis 2018, pp. 240–43). |

| 24 | By comparing photographs of the lararium over time, we discern that at some point in the twentieth century, the holes for the nails were covered with plaster. Compare, for example: (Fröhlich 1991, Taf. 2.1; Giacobello 2008, fig. 17). |

| 25 | See: (Van Andriga 2000) for a complete catalogue of the compital shrines of Pompeii. |

| 26 | Indeed, one only need to think of sculpted garlands on Roman altars. One of the most famous examples is on the upper registers of the interior of the Ara Pacis Augustae in Rome, with large floral garlands hanging in-between bucrania. There is also evidence on some Roman sacrificial altars for appendiges carved into the stone that allowed worhippers to affix physical garlands on the altar itself (Bowerman 1913, p. 77; Honroth 1971). |

© 2020 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rogers, D. The Hanging Garlands of Pompeii: Mimetic Acts of Ancient Lived Religion. Arts 2020, 9, 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020065

Rogers D. The Hanging Garlands of Pompeii: Mimetic Acts of Ancient Lived Religion. Arts. 2020; 9(2):65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020065

Chicago/Turabian StyleRogers, Dylan. 2020. "The Hanging Garlands of Pompeii: Mimetic Acts of Ancient Lived Religion" Arts 9, no. 2: 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020065

APA StyleRogers, D. (2020). The Hanging Garlands of Pompeii: Mimetic Acts of Ancient Lived Religion. Arts, 9(2), 65. https://doi.org/10.3390/arts9020065