1. Introduction

In October 2012, David Cameron, then Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, announced a major programme of commemorative activity to mark the centenary of World War One. Central to this programme, which included battlefield tours for schools and a major revamping for the Imperial War Museum in London, was funding for visual arts projects across the country (

Cameron 2012). The government’s initial commitment of £50 million towards the overall programme was expanded over the period of the centenary several fold, with support channelled through various funding streams including the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Arts Council England, the National Lottery Community Fund, the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as directly from the Department for Digital Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS). Moreover, alongside these funding bodies the government established a bespoke organisation, 14–18 NOW, to deliver the commissioning of a four-year arts programme across the country. 14–18 NOW received £55 million in combined funding of which close to £30 million came from the government and Lottery distributors (

DCMS 2019b, p. 54).

This spending commitment was surprising at a time when the Conservative-led British government had embraced an official policy of “austerity”, which made deep cuts to public spending, including to arts funding.

1 The decision to invest in a mass programme of arts projects and public engagement was bolstered, however, by the perceived success of Britain’s Cultural Olympiad, a four-year programme of arts events culminating in the London 2012 Festival (which in fact included events across the country) to coincide with Britain’s hosting of the Olympic and Paralympic Games. The Cultural Olympiad had been initiated under the previous Labour government and did not go uncriticized for its diffuseness.

2 Nonetheless, as excitement around the Olympics themselves grew, the London 2012 Festival, which involved 25,000 artists, was greeted with enthusiasm by the broadsheet press (

Garcia and Cox 2013, p. 11).

3 Cameron’s announcement thus rode the wave of the general euphoria that had greeted the Olympic Games festivities in Britain. The appointment to the directorship of 14–18 NOW of Jenny Waldman, who had previously been the London 2012 Festival’s Creative Producer, underscores this point. 14–18 NOW and the larger government funded programming around the centenary clearly sought to build on the model that had been used for the Cultural Olympiad.

The idea of the Cultural Olympiad had emerged almost a decade earlier as part of Britain’s London 2012 Olympics bid, in an era when Tony Blair still led a Labour majority government and before the global financial crisis of 2007–08. The impact of the financial crisis in Britain, however, coincided with the launch of the Cultural Olympiad. The Labour government’s failures in managing the financial crisis led to a hung parliament in the 2010 general election, resulting in a coalition government of Conservatives and Liberal Democrats. The policy of austerity that Cameron’s government introduced was in part a response to the impact of the global financial crisis, but it also represented a different ethos regarding government spending on social welfare and funding for the arts. Thus, the Olympic Games and the London 2012 Festival took place in a very different political climate from that in which they had first been imagined. That the Cultural Olympiad was perceived to have succeeded in creating a sense of well-being and social cohesion, in a country divided politically and still reeling from the global financial crisis, no doubt made it particularly appealing to the Cameron government as a model for future national cultural events.

At the same time, the national divisions that the hung parliament of 2010 signalled became apparent in other areas besides economics. In 2012, the UK government granted the Scottish Parliament the right to hold a referendum on Scottish independence. The referendum, which took place on 18th September 2014, barely a month after the start of World War One centenary commemorations, was hard fought, returning a majority of only 55.3% for remaining within the UK. Two years later, following a general election in 2015 that returned a Conservative government, the UK voted to leave the European Union by a 51.89% majority in a referendum that had been a central commitment of the Conservative’s 2015 manifesto. This referendum was held barely seven days before the centenary of the Battle of the Somme, when Jeremy Deller’s “we’re here because we’re here”, the centrepiece of 14–18 NOW’s programming, was performed. The fallout from the referendum on EU membership resulted in several years of political and constitutional chaos for Britain, against whose backdrop the remaining two years of centennial programming unfolded.

4The Olympic Games are a very different context for arts programming to the centenary of World War One. While the former invites an openly celebratory approach to global relations, the centenary of a war fought on a global scale invites another set of responses. As this brief account makes clear, however, the differences between the two events go beyond these considerations. The cultural moments in which the Cultural Olympiad and the World War One centenary commemorations were conceived and delivered were highly distinct, shaped as they were by global and national upheavals. Thus, for all that David Cameron might have envisioned a programme that repeated the uplifting and uniting model of the Cultural Olympiad, the centenary commemorations were more complex in the issues they addressed and the contexts in which they were produced.

Another key difference between the Cultural Olympiad and the centenary commemorations is that in the former there was no sense that other countries might be responding on a similar scale or in similar ways to the same event. Tied as it was to Britain’s 2012 Olympic bid, the Cultural Olympiad was specific to the UK as the Olympic host. By contrast, the centenary of World War One was marked with greater and lesser emphasis in many of the war’s combatant nations. Indeed, one of the indicators of value noted in the British government’s 2019

Lessons from the First World War Centenary report was the collaboration with foreign government agencies that the commemorations involved (

DCMS 2019a, Question 38).

Furthermore, whereas the Cultural Olympiad was not accompanied by a particular mass of other related art works, alongside the commissions and projects that arose from the DCMS-led schemes of funding, other commissions and arts projects responding to World War One were undertaken to coincide with the centenary quite independently. Beyond the remit of the programme envisioned by the DCMS and its funding partners, artists and community groups responded in their own ways and with their own motivations to the commemorative prompt that the centenary offered. As we shall see this was not without its challenges for artists and curators whose projects developed independently. Moreover, inevitably these projects remain unaccounted for in the formal evaluations undertaken by the DCMS, 14–18 NOW, and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, whose focus was on the work undertaken with their particular support. This is problematic insofar as it means that the sometimes quite different experiences of those artists and curators are not present to nuance and to challenge the larger and largely positive narratives that emerge from the evaluation reports.

5The evaluations that have been undertaken by 14–18 NOW and the National Lottery Heritage Fund, as well as the DCMS report, have understandably focused primarily on public benefit. Given the level of public funding channelled into the four-year programme, in a political climate otherwise characterised by unrelenting economic austerity, the funders were keen to demonstrate the value for money they had delivered for the nation. The DCMS report, for example, organises its evidence under the following headings: “Connecting to younger people”, “A cross-nation approach”, “Reaching new audiences”, “Lasting connections”, “The role of the DCMS” (

DCMS 2019b). Even the section presented under its opening heading, “The arts and commemorations”, focuses wholly on the public reception of the arts as a mode of commemoration, rather than on the impact of commemoration on artistic practice. Tellingly, none of the witnesses who provided oral evidence to the DCMS committee were themselves practising artists and only one of the 119 written submissions to the committee considered the impact of the centenary for professional practice specifically from an artist’s perspective.

6The independent evaluation commissioned by 14–18 NOW,

Crossing Divides, did engage directly with artists through a survey and focus groups. Consequently, the report draws more on the voices of artists in its evaluation. Nonetheless, like that produced by the DCMS, the report structures itself around the public reception of 14–18 NOW’s programme with headings like, “Engagement of new audiences”, “How was this reach achieved?”, “Bridging social divides”, “History and young people”, “Culture-led regeneration”, “Can arts and heritage bring us together?” Thus, although

Crossing Divides does raise questions about artistic practice, for example the experience that “artists from minority ethnic groups felt obliged to produce work largely or solely about race or about their own community” (

Rutter and Katwala 2019, p. 18) and a concern that the arts should not be instrumentalized (ibid., p. 26), the more particular and affective experiences of artists remains unexamined.

Yet, if the “arts are a core part of [British] national life”, as the DCMS report claims, it is important that we listen to and understand the experiences of the artists themselves (

DCMS 2019b, p. 6, para. 15). What motivated artists to produce work that responded to a war fought a century ago? What did

they learn and feel and how were

they changed by their experience of commemorative art-making (questions far more commonly asked of non-professional, “general public” participants in the centenary’s events)? And how were centenary arts projects informed by the long international history of artistic and memorializing engagement with World War One?

To begin to answer these questions, in 2019 I undertook ten interviews with a range of people who had been involved in centenary arts projects that responded to World War One. Using the same basic set of open-ended questions for each one-to-one interview I spoke with artists, curators, and those who had been involved professionally in community art projects. My interviewees came from across the Midlands and North East of England, Scotland, and Aotearoa New Zealand. Their centenary-based work had been exhibited locally, nationally, and internationally. Four of those I interviewed were people with whom I had previously collaborated on World War One-related projects (Cat Auburn, Christine Borland, Kay Easson, and Gary Richardson), two I had met briefly in professional contexts (Jo Meacock and another curator), while the other four (Dalziel + Scullion, Kenny Hunter, Sarah McClintock, and another artist) were not known to me personally before the interviews. For each interview, I approached interviewees individually by email first, and supplied them with the basic set of questions in advance of our meeting. My interview with Sarah McClintock, who is based in Aotearoa New Zealand was conducted by Skype, all other interviews were held face to face, often in the interviewee’s studio or place of work. Each interview, roughly half an hour to an hour long, was recorded and transcribed. One curator and one artist chose to maintain anonymity.

My aim was to create a snapshot of the impact of working on World War One related arts projects during the centenary for a range of professionals and in a range of contexts. I wanted to ensure I included those who had worked on local community projects as well as those whose work was part of national programming, and those who had worked independent of any kind of public programming. Likewise, I wanted to represent work across a variety of visual media. Finally, I wanted to capture what differences there might be between the experience of artists and curators working in the UK and those working overseas and thus outside the remit of the British government’s larger centennial programming. These priorities informed the selection of my interviewees. Inevitably, with such a small sample and one drawn in part from pre-established networks, the findings are not conclusive, nor are they intended to be. They reflect individual experiences of individual professionals. Indeed, what I sought to capture in the interviews was exactly this individual experience, in order to highlight the importance of taking into account those experiences when reflecting on, and accounting for, the long-term impact of World War One centennial art-making.

In some instances, the art projects with which interviewees had been involved arose from specific World War One-related commissions or funding calls; in others, artists chose independently to respond to the war, without the prompt of a particular scheme. Likewise, while some projects were supported through public funding ring-fenced for centenary activities, others were developed and came to fruition through different routes, sometimes with minimal funding altogether. These variables inevitably gave rise to variety in the responses of interviewees; although, as we shall see, there were also some key ideas and experiences that were shared by almost everyone. In what follows, I focus particularly on the responses of the artists and curators interviewed, in terms of the research they undertook, their reasons for pursuing their projects, and the effects it had on them emotionally and professionally.

2. The Experience of Commemorative Art Making

Over the century since the conflict broke out, World War One has given rise to an astonishing range of artistic production in fine art, sculpture, film, music, literature, and more recent forms such as computer games. During the war itself, artists responded in a variety of ways: as formally appointed war artists; as combatants recording their experiences privately; as professionals producing images to be used for propaganda, fundraising and roles of honour; and as opponents of the war, using their art as a form of protest. At the end of the war, artists continued to respond both personally and professionally. For example, the Imperial War Museum, which was founded in 1917, commissioned William Orpen to record the peace process at Versailles during the spring and summer of 1919.

7 While the Imperial War Museum was founded with the intention of preserving a wide range of material artefacts from the war, it is telling that it also sought to sponsor the creation of artworks that recorded the war and its aftermath. Indeed, both at the time and in the years following the war, art was crucial to public understanding and commemoration of the war. Then as now, art provided a medium by which the experience of the war was mediated.

Another example which demonstrates how art came to provide a focal point for remembrance is the painting, “Menin Gate at Midnight” (1927) by the Australian artist, Will Longstaff. The painting was gifted to Australia in 1928 by Lord Woolavington and was toured around the country. At the same time, the image was reproduced both as signed editions and in cheaper versions, which were sold door to door, for fundraising. The circulation of “Menin Gate at Midnight” in its original and reproduced versions thus became an important way for Australians to enter imaginatively into the landscape of the war in Europe and to commemorate the war’s losses. Such artistic mediation continued throughout the twentieth century, with visual artists and those working in other media returning again and again to World War One as a site for artistic interrogation.

8 The persistent significance of World War One is reflected in the consolidation of remembrance for both World Wars in annual Armistice Day commemorations. Thus, the war continues to act as a key trope in visual representations and cultural understanding of modern warfare in Europe, even where it is incorporated into larger commemorative narratives.

Those I interviewed engaged in highly varied ways with this scholarly and artistic body of work but were also repeatedly drawn to other kinds of information and materials as sources of inspiration. Of all the artists I spoke with, Kenny Hunter was the most explicit about his engagement with traditions of memorial art. As a sculptor who has worked on several commemorative commissions in the past, this is perhaps not surprising. His prior works include “Stand Easy” (2012), an armed services memorial in Leicester, and “Citizen Firefighter” (2001). Commissioned by the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service, this latter work become a significant unofficial site of remembrance for 9/11. Hunter was commissioned by Southwark Council to create a permanent war memorial in Walworth Square, London. Unveiled in 2018, the final work, in bronze, presents a life-sized youth standing on the cast of a section of a large ash tree that had been felled in the borough (

Figure 1).

9Hunter acknowledged that “if you work exhaustively on research … it can make you … overly conscious of the gravity of the subject and about … this back catalogue as well”. Nonetheless, he was keen to find examples from artists who had “something to teach him”. Charles Sargeant Jagger provided one such model. Jagger’s Royal Artillery Memorial at Hyde Park Corner includes a carved-stone howitzer and, among the soldiers depicted, a dead body. As Hunter reflected, “that was a real jarring image for, you know, 1919 and 1920 to look at that”. The disruption of the symbolist traditions of memorial sculpture that the dead body represents appealed to Hunter, but so did Jagger’s attention to detail, which Hunter read as a form of honouring the dead, as if Jagger was saying “I’m getting all your buttons exactly the right size. They’re exactly the right space between them … every detail of your uniform has been lovingly recreated”.

In our discussion of his figurative practice, Hunter invoked both Jeremy Deller’s 14–18 NOW commission, “we’re here because we’re here”, alongside Rodin’s “Burghers of Calais” to illustrate the power of the human figure to “move people”. The Burghers of Calais was commissioned by the City of Calais in 1884 to commemorate the Hundred Years’ War. Rodin’s sculpture depicts the six city burghers who gave themselves up to the besieging English in order to save the city’s citizens. For Hunter, the “Burghers” represent “a huge leap forward” for sculpture because Rodin’s vision was for them not to be on a plinth but at ground level: “we then share the same space as the figure … we walk around it, we eyeball it … [and] it was done … through a war memorial commission”. Similarly, the “intimacy” of Maya Lin’s Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial inspired Hunter, its “touchability”, like that of the “Burghers”, creating an “open, engaged, but not judged” space in which work and viewer co-exist. Later in our conversation, Hunter noted the influence of “Pietà”, in the Neue Wache in Berlin, on the conception of the Southwark Memorial. This sculpture is a version of Käthe Kollwitz’s “Pietà” (1937–1939), commissioned from Harald Fraake by the former German Chancellor, Helmut Kohl. Installed in 1993, the sculpture appears diminutive in the vast space of the Neue Wache, despite being four times the size of Kollwitz’s original “Pietà”. The scale of the sculpture’s human form within the space of the Neue Wache spoke to Hunter of our human vulnerability to the “mass turning of the wheel of history:” “the scale is wrong … you’re going to get crushed, you’re going to get obliterated”. This affective use of scale thus came to inform Hunter’s choice of a relatively small human form against the vastness gestured to by the tree trunk section on which the youth stands.

While the potential of figurative sculpture was a rich resource for Hunter, he was also highly alert to the ways in which artists are often expected to choose between working in abstract and figurative modes, an issue that other interviewees raised as well, particularly those producing figurative work who felt this mode was often seen as secondary to abstract and conceptual art practices. Hunter observed that just as figurative work can easily “lurch into sentimentality”, abstraction “can work conceptually … but fail to … connect on a human level”. Suggesting Daniel Libeskind’s design for the Jüdisches Museum Berlin as a positive example of abstraction, he noted how abstraction in architecture or sculpture might create disorientation and a sense of restriction that “plays on, sort of, primal triggers of fear”. Nonetheless, Hunter returned repeatedly throughout our discussion to the “Burghers” and their encapsulation of “eternal isolation” as a paradigm for war memorial sculpture. What emerged from the interview was thus a striking sense of Hunter’s rich engagement with nineteenth and twentieth-century memorial art and architecture, and in particular a strong commitment to the figurative tradition within that history.

If many of Hunter’s creative interlocutors were also often his predecessors, Christine Borland, one of the artists commissioned through 14–18 NOW, benefitted from the opportunity to network with other artists engaged in centenary commissions that 14–18 NOW enabled. Borland came to prominence as a YBA artist in the 1990s and was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1997. Her work, which uses a variety of print, sculptural and found media, frequently engages with memory and biological fragility. Being part of 14–18 Now’s national programme meant Borland couldn’t help but be aware of other contemporary work going on, but she also sought this out: “I wanted to hear more, and I thought it would be nice to situate what I was doing within a broader context of these projects”. Her research thus engaged directly with that of her contemporaries as well as historical and contemporary examples of public and memorial sculpture. These interests informed the commissioned work, “I say nothing”, whose central piece is a large scale photosculpture. Drawing from the past, Borland cast the masks for her photosculpture models from a bronze by the sculptor Paul Raphael Montford. Despite its name (“Peace and War”) and its date of commission (1914) Montford’s sculpture was in fact unrelated to World War One. It was one of four thematic sculptures he made to adorn the Kelvin Way Bridge outside the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow, which was Borland’s partner organisation for “I say nothing”.

10 Having worked in Glasgow for many years, the history of “Peace and War” was familiar to Borland. Casting the masks from Montford’s sculpture provided an opportunity to rework his historical representation of war to new ends. Likewise, Borland’s decision to use photosculpture methods illustrates this engagement with contemporary and historical models further (

Figure 2). These methods drew on the one hand on the innovations of Françoise Willeme, the nineteenth-century photographer credited with inventing photosculpture, and on the other on the recreation of Willeme’s working methods in the recent work of contemporary artists, Louisa Minkin and Ian Dawson.

11 Thus “I say nothing” brought into conversation contemporary and historical traditions of public sculpture, memorialisation, photographic record and reproduction, in such a way as to keep each tradition visible within the work even as the work began to synthesize them.

Informed as “I say nothing” was by historical and contemporary sculptural precedents, Borland’s main inspiration nevertheless came from her research in the Glasgow Museums Resource Centre, exploring items in the collection related to World War One. Borland’s access to the Resource Centre was facilitated by the 14–18 NOW commission, and the prestige of the commission, and of Borland herself, opened doors in ways that artists working independently were not always able to benefit from. In addition, the two year’s worth of funding that the commission afforded, which included a year-long residency in the Resource Centre working through handlists, calling up items, as well as studio time to develop work out of the ideas that the items prompted, was hugely enabling. Having time, in particular, allowed her to develop a reflective mode of working with the collection items. Describing her methods, Borland observed that it “really was just things that jumped out at me, I wasn’t questioning why … I just let them … find their own kind of pecking order”. Borland was not simply interested in the items themselves, however, but also began to investigate the processes by which they were accessioned, catalogued, handled, and conserved. She developed a close working relationship with Stephanie de Roemer, Conservator of (3-D Art) Sculpture/Installation Art, and her decision to envelop the individual panels of the photosculpture in glassine (a material historically used to wrap items in storage) was informed directly by this interest in handling and conservation (

Figure 3).

Other artists working independently did not always experience the same accommodations from which Borland benefited, and spoke of the challenges of accessing physical collections and the personal financial cost that obtaining research materials entailed. For these artists, online research was especially important, particularly where their works were responding to transnational colonial histories whose archives are fragmentary. This research was aided considerably by the centenary, which prompted many organizations to expand and improve their digital collections. Large scale international digitization projects such as (

Europeana 1914–1918) were already underway in the run-up to the centenary, but artists noted how access to relevant digitized materials increased exponentially between 2014–2018, driven by the heightened public interest that the centenary brought with it and the funding channelled into digitization projects as a result. Digital resources provided access to images with which artists worked but also enabled artists to shape their methods too. New Zealand artist, Cat Auburn, for example, drew on the lost art of hair wreathing, for “The Horses Stayed Behind”, which she taught herself from digitized nineteenth-century manuals found online.

Like many others I interviewed, Auburn was interested in telling new stories about the war that had not been represented previously. Auburn’s project was undertaken during her Tylee Cottage Artist Residency at the Sarjeant Gallery, Whanganui in 2014–2015. Like Borland, Auburn works across a range of media, including photography and film as well as sculpture and textiles. She introduced her project as prompted by “a particular … New Zealand narrative that I’d never heard of before and I found quite fascinating”. This story was of the New Zealand mounted riflemen and the horses that were sent from Aotearoa New Zealand with them to the Middle Eastern front. Until the centenary, this was a story that was barely told in Aotearoa New Zealand and while other projects over the centenary began to uncover the stories of both the horses and Aotearoa New Zealand’s involvement in the Middle East, Auburn’s work contributed a unique fine art approach. Auburn noted that her project, “The Horses Stayed Behind”, was informed by “a lot of research on the actual story … not so much about … individual soldier stories, but [the] agreed upon memory”. Auburn’s interest in the “agreed upon memory” reflected her concern not only to tell the story of the men and their horses, but also to unpick the grand narratives of the war in Aotearoa New Zealand, which framed Gallipoli as a form of sacrifice from which the modern nation emerged. By contrast, the forgotten history of Aotearoa New Zealand’s involvement in the Middle East complicates this grand narrative, associating the commonwealth forces with the struggle between British, French, and German colonial powers for control of the region. This struggle was played out through the war and its immediate aftermath, and the impact of that struggle is still felt in the region’s divisions today. The exploitation of the war for colonial expansion thus draws attention not only to the role played by Aotearoa New Zealand in Middle Eastern history but also returns our attention to Aotearoa New Zealand’s own fraught history of colonization.

Auburn was more ambivalent about engaging with the work of other artists than Borland and Hunter. At the time that she began to explore the story of the mounted riflemen “around 2012/13”, she “wasn’t really aware of too many artists who were making contemporary artwork” about World War One, noting that it was hard to know at that point what other artists might have planned in relation to the centenary.

12 Although she explored Michael Parekowhai’s “Pare Kawakawa” and Helen Pollock’s work, at the same time she admitted that she “definitely blocked out what other artists had done”. Auburn’s isolation from the works of others was thus in part a choice, as a way of making space for her own creative ideas to develop, but also a result of not being part of a larger programme. The impact of working independently was commented on by other artists too, particularly where potential partner organisations did not have “the tools to act as hosts or brokers” for large-scale projects or commissions. For some, that isolation threatened to undermine their belief in their own practice, but what they also made clear was that their commitment to their subject matter sustained their work: “I wasn’t doing it because of fashion and trends. It’s because I’m passionate about it”. Moreover, for many of the artists I spoke with, as word spread of their work on the war, colleagues, friends and even relative strangers started to share photographs, stories, and memorabilia which fed into the creative process.

Indeed, one of the consequences of mass recruitment in Britain during World War One is that many today have memories of older relatives who took part, even though there are no longer any surviving combatants. Personal memory and engagement with ephemera and memorabilia thus became an important form of research on which artists and curators drew. Central to Borland’s photosculpture, for example, was a feeder cup. During the war these ephemeral china utensils served two purposes: to provide liquid sustenance to injured soldiers, and to force feed suffragettes on hunger strike. The contradictory uses of the feeder cup, communicating care and violence, caught Borland’s imagination and in her photosculpture she choreographed her models in two poses based on images and accounts of the feeder cups’ uses.

Several interviewees referred to old family medals and familial stories that prompted them to consider how their art might communicate the otherwise obscured personal histories of the war. Not that they sought to tell only the story of an individual, but everyone I spoke to expressed a desire to resist the inevitably homogenizing effect of collective memorialisation by which the affective impact of individual stories becomes subsumed in larger (grand) narratives. Dalziel + Scullion’s “Sàl” exemplifies this kind of engagement particularly. Dalziel + Scullion’s work is marked by its engagement with the natural world, drawing on a variety of plastic and visual media. “Sàl” was a 14–18 NOW-funded collaboration with folk musician, Iain Morrison, to commemorate the loss of the Iolaire, an Admiralty yacht carrying returning troops at the end of the war. The work comprised Morrison’s composition and performance of a suite of music accompanied by videos composed by Dalziel + Scullion.

In the early hours of New Year’s Day, 1919, the Iolaire foundered on the coast of the Isle of Lewis, barely a mile from port and but a few yards from shore. So rough were the seas, however, that over 200 of the 283 recorded on board drowned, including Morrison’s great-grandfather. Dalziel + Scullion recalled the “raw emotion” with which the event was still remembered, and the concomitant collective forgetting to which such loss gave rise. Having worked as landscape artists in the Hebrides for many years, they had been aware of a “sort of atmosphere” and knew the story of the Iolaire but had “never really looked into it in any depth … the whole thing [was] dormant”. They explained that “there’s a quietness around it … for years no one spoke about it”. As much as reading books, they drew on what Morrison told them himself and the history that Roddy Murray (Head of Visual Arts and Literature at their partner organisation, An Lanntair) shared with them as they developed the project. These accounts, shared personally, reshaped how they saw the landscape in which they had worked for many years. At the same time, their response to the stories Morrison and Murray told them informed Morrison’s compositional process too. Dalziel + Scullion were particularly struck by the gendered impact of the loss of the Iolaire, which Morrison had illustrated for them with photographs of his great-grandmother. The loss of so many men left many women on the island without husbands, fathers, brothers, and sons. These women had to bear the heavy labour of running their crofts single-handedly. Responding to this history, Dalziel + Scullion developed footage of “interior domestic scenes”, which, despite his sharing of family stories, Morrison had not “thought about as much” in his own music. Having seen Dalziel + Scullion’s footage, Morrison returned to his composition and added two tracks called “Ise” (Woman). This instance of mutual influence exemplifies the ways in which research, creative practice, and personal interest were braided in the work of everyone with whom I spoke.

Dalziel + Scullion’s interest in the impact that the loss of the Iolaire had on the female population of Lewis also reflects the shared concern of all the interviewees to tell new stories through their work. For almost all concerned their motivation was not to create a work that reflected the inherited narrative and visual tropes of the war but rather to provide new perspectives. This often meant invoking individualised stories to bring to life unexplored and untold histories. Nonetheless, as we shall see, these individual stories were often used to gesture to larger narratives.

Artists sought to represent individual experiences of the war in a variety of ways. Dalziel + Scullion’s long sequence using the faces of local islanders, reminds audiences of the individuality of each man lost when the

Iolaire foundered (

Figure 4). The frame crops each head closely and the camera holds long enough for us to become aware of each face’s idiosyncratic features: freckles, cracked lips, wrinkles, and the colour of irises. Meanwhile, the cinematic centrepieces of “Sàl”, “Cogadh II” (War II), and “Roinn IV” (Commune/Share IV), take a very different approach but with the same aim. Here a solo dancer performs in an empty studio space before a static camera (

Figure 5).

13 Shot partly in and partly out of focus the choreography and gesture communicate both the vitality of the young male dancer and the loss of that vitality in the violence of war. The dancer thus becomes starkly individualized and at the same time, in Dalziel’s words, “putting him out of focus [meant] it didn’t become about him … one person … any longer, he was a universal archetypal individual”.

While Dalziel + Scullion’s work engaged with the local community as participants in their filming as well as sources of stories and information to guide their thinking, Auburn’s work engaged communities across the islands of Aotearoa New Zealand. Auburn used horsehair to make her work. To gather the quantities necessary, she and her curator, Sarah McClintock, travelled the country going to agricultural shows and equestrian events where they asked owners if they could take small quantities of tail hair. Once word spread in the equestrian community, owners began to send in donations of tail hair from across the country. Often, these donations were themselves given in memory of other family members and animals lost. From each donation Auburn made an individual rosette and the placement of each rosette in the work was mapped so that donors could find it if they visited the work when it was exhibited (

Figure 6).

14 Auburn also used Facebook to share images of the individual rosettes with donors as they were made, giving them a further sense of involvement in the making of the work.

This investment in the work by the community was a surprise to Auburn, but one that recalled the origins of hair wreath traditions:

the function of Victorian hair wreaths was very much about community … So like a church group … Everyone would donate their hair and this hair wreath could become … a really physical map of the community … And I felt … in the same way that was sort of happening across the equestrian community in a really physical way.

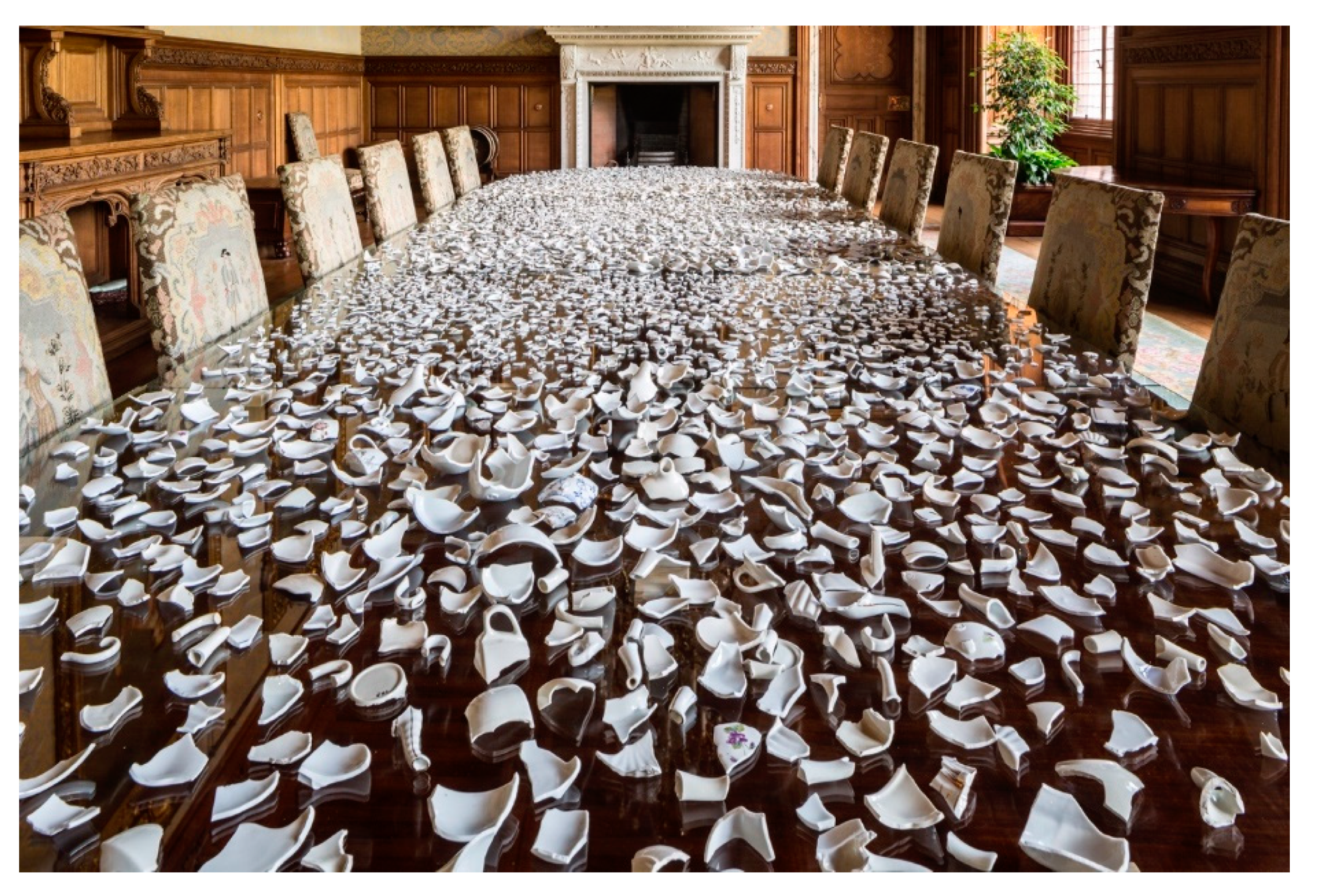

Here, as with Dalziel + Scullion’s films for “Sàl”, there is an oscillation in “The Horses Stayed Behind” between the individual, the community, and the universal. Each rosette, like the faces in Dalziel + Scullion’s work, speaks in the first instance of an individual, but their placement among others begins to “map” the community physically in order to communicate a larger and potentially universal narrative of commemoration. A very similar aesthetic is at play in Borland’s installation at Mount Stuart, “to The Power of Twelve”, which ran in 2018 concurrently with her 14–18 Now commission, “I say nothing”. In particular, both “to The Power of Twelve” itself, 444 hand blown clear glass spheres placed on the floor of the Marble Hall (

Figure 7), and “The China Harvest”, which laid out the exploded fragments of 144 ceramic feeder cups on the banqueting table of the Dining Hall (

Figure 8), use the cumulative impact of the individual to prompt a reflection on personal, communal and universal loss.

15As for the other interviewees, Hunter wanted his memorial to encompass the larger complexities of both the World War One and of war more generally. The parameters of his figurative medium and the public location of the final work in Walworth Square, added particular constraints. His approach to the same challenge, to represent individual, communal, and universal experience concurrently, was therefore quite different. Rather than multiplying notations of the individual (like Borland’s glass spheres), Hunter’s figure is made to stand metonymically for the impact of war. Gestureless and wearing civilian clothes, Hunter’s youth diverges starkly from traditional public memorial sculpture and even from the particularised realism of Jagger’s Royal Artillery Memorial. As Hunter explained, his youth is intended to represent all victims of war, civilians as much as combatants. This was not simply an ideological choice, but also responded to the context for the memorial. The borough in which the Southwark Memorial stands is home to a considerable number of people internationally displaced by conflict, and Hunter was keen to reflect their larger experience, both the trauma of war and “the idea of human resilience”. Hunter’s youth, like Dalziel + Scullion’s dancer, thus becomes “a universal archetypical individual”.

Nonetheless, Hunter was aware of the ways that contemporary “identity politics” can trouble the non-symbolic representation of the human form in figurative work. Citing critiques of the maternalism of Kollwitz’s “Pietà”, Hunter reflected on the challenge of creating a “human figure” that does not invite questions of identity, such as “well, why is it a boy?” Such concerns had clearly informed his aim of making the figure “quite mixed race”. In answer to his own hypothetical question about gender, Hunter went on to explain, “I almost felt that if I put a female up there … identity would’ve been more of a feature in a strange way”. Setting aside the gender normative assumptions of this answer, what Hunter’s meditation of these issues illuminated was the tension inherent in his desire to represent universal experience in an individualised (“contemporary”) human figure, while resisting the impulse to identification. Hunter’s work returns us to the oscillation between the individual, the communal and the universal that Dalziel + Scullion’s phrase “a universal archetypical individual” precisely sums up.

While Hunter had to negotiate the identity politics of his figurative work, those working in conceptual arts faced a different set of challenges in engaging their audiences with the stories that they wanted to narrate. Thus, while the story of the horses caught imaginations in Aotearoa New Zealand, this was accompanied by a frustration for Auburn that audiences seemed unwilling to engage with the more complicated story of New Zealand’s colonial involvement in the Middle East: “People would much rather talk about the horses than the men and the men’s experience”. Audiences were able to make the connection between the central piece of “The Horses Stayed Behind” and the loss of the horses but were unwilling to take the next step to consider the men or the larger and stickier colonial history of the war of which the New Zealand mounted rifleman’s story was a part.

Another challenge for many of the artists and curators interviewed was negotiating their own feelings about war and, more precisely, the military. Two of the curators with whom I spoke expressed strong pacifist convictions and reflected on how those convictions related to their involvement in the commemorative projects. Jo Meacock from Glasgow Museums observed that she “found [herself] in a situation that [she] didn’t expect to be in” when she began to work on an exhibition of Frank Brangwyn’s work. Brangwyn’s series of lithographs, which tell the story of a soldier who is blinded and hospitalised but returns home to learn a new trade, had been sold to support St Dunstan’s Hostel for Blind Soldiers and Sailors in London. Meacock worked closely with the charity, Scottish War Blinded, in the design of the exhibition both to make it accessible to those with visual impairment and also to help sighted visitors consider the sensory experience of visual impairment. Meacock reflected that while previously she had “never been that interested in war art” and indeed had been “quite suspicious” of the military and “conflict”, her work curating a number of different World War One-related exhibitions during the centenary, including Borland’s “I say nothing”, kindled a new interest “in war art and the reasons to make art”. On the one hand, this experience opened up a new appreciation for how art might connect with war tangentially “rather than dealing with the big issues around conflict and the machinery of war”; on the other it gave her “a greater appreciation of people who make sacrifices … more [awareness] of the personal stories rather than just thinking generally about the military in a negative sense … thinking much more about actually, who has the power and who are the victims”.

Meacock’s experience of gaining new insights into the war was reflected by Auburn too. While, as has already been noted, Auburn felt frustration with the reluctance of some audiences to consider the more difficult stories with which her work engaged, she nonetheless admitted that prior to her work for “The Horses Stayed Behind” she herself had struggled “to think of [the war] as personal” rather than on a “national, global” scale. Another curator welcomed the opportunity to use the arts to challenge dominant narratives about the war that the centenary offered: “that whole thing around World War One … and the commemoration of it … particularly at the moment in our current political climate, there’s a lot that’s not talked about”. For her, the centenary made possible the display of conceptual art whose “unravelling” of traditional stories about the war could challenge “a far right agenda of kidnapping commemoration”. She pointed to the risk that commemorative exhibitions (historical or artistic) could end up manipulating “sentiment” not least in the service of larger political narratives. Implicitly and explicitly she called into question the political co-opting of the centenary commemorations in the UK and the ambivalence with which artists and curators responded: “I don’t even know if it’s the Devil’s shilling that you’re taking you know, but you take the shilling and you do the Lord’s work”. Thus, despite her misgivings about its political framing, she saw the centenary as a chance to “probe and provoke … thinking”. As she reflected: “presenting things as being complex and sometimes contradictory, well for me makes the best art, but also meant that I felt more comfortable in that space”.

A final challenge that each interviewee raised was their sense of responsibility. This challenge was also a motivation, inspiring artists and curators to pursue their work even when things did not run smoothly. One artist talked about the painstaking attention she gave to reproducing the images of soldiers in her work as a form of “respect” for their memories: “piece by piece unpicking their face, their body, their ears, their facial expression”. Recreating the figure accurately was a mode of care and became itself an act of commemoration. At the same time this sense of responsibility to the past was accompanied by a responsibility to the present. Borland, for example, observed “the real burning desire to … always be thinking about a contemporary relevance” to her subject matter. For Dalziel + Scullion, those responsibilities were intertwined. The foundering of the Iolaire remains a “very sensitive subject matter” they explained, “it was handled quite poorly … by the power of the day and … so there’s a lot of kind of anger around that [still]”. Comparing their previous work on the island they observed that it had had “no responsibility … it was just purely a physical and emotional response to the surface”. In contrast, their collaboration with Morrison for “Sàl” gave them “a much deeper … understanding of the whole place”, which at the same time instilled their sense of responsibility to the community. Consequently, “if you have an art gallery show and it doesn’t go down well you’ve only let yourself down” whereas with “Sàl” they felt that would be “letting the whole community down” if the work did not cohere. Others expressed a sense of responsibility to prompt conversation. McClintock, for example, argued that “the role that art can have is not to answer any questions, not to put full-stops on anything. It’s about triggering or at least allowing conversation to continue”. Another artist similarly talked about her work “as a strategy” of seduction by which audiences are drawn in, “and once they’re there … then it begins: that whole journey of discussion”.